In the last ten years an attempt has been made to reinstate Roman art in the proud place it occupied in the eighteenth century. Then before the Elgin marbles were brought to London or the Hermes of Praxiteles was unearthed, such statues as the Apollo Belvedere, such monuments as the column of Trajan were regarded as the masterpieces of antique art. During the nineteenth century, as the beauties of Attic art were revealed, the pendulum swung so far to the other extreme that archaeologists were prone to disregard Roman art entirely. The crudest archaic statue from Greek soil was prized more highly than the most magnificent monuments of Rome. Now, however, a reaction has set in; champions of Roman art have arisen who are claiming for the sculptures of the imperial period both originality and high artistic worth. The question of the justice of their claims involves some of the most interesting problems of sculpture, such as the relative merits of low and of high relief and the possibility or the advisability of representing in relief a scene in three dimensions, of indicating, that is to say, depth as well as length and breadth. In view of the current discussion of these problems, the acquisition of a Roman relief of the imperial period is peculiarly timely.

Museum Object Number: MS4916A

Image Number: 3324

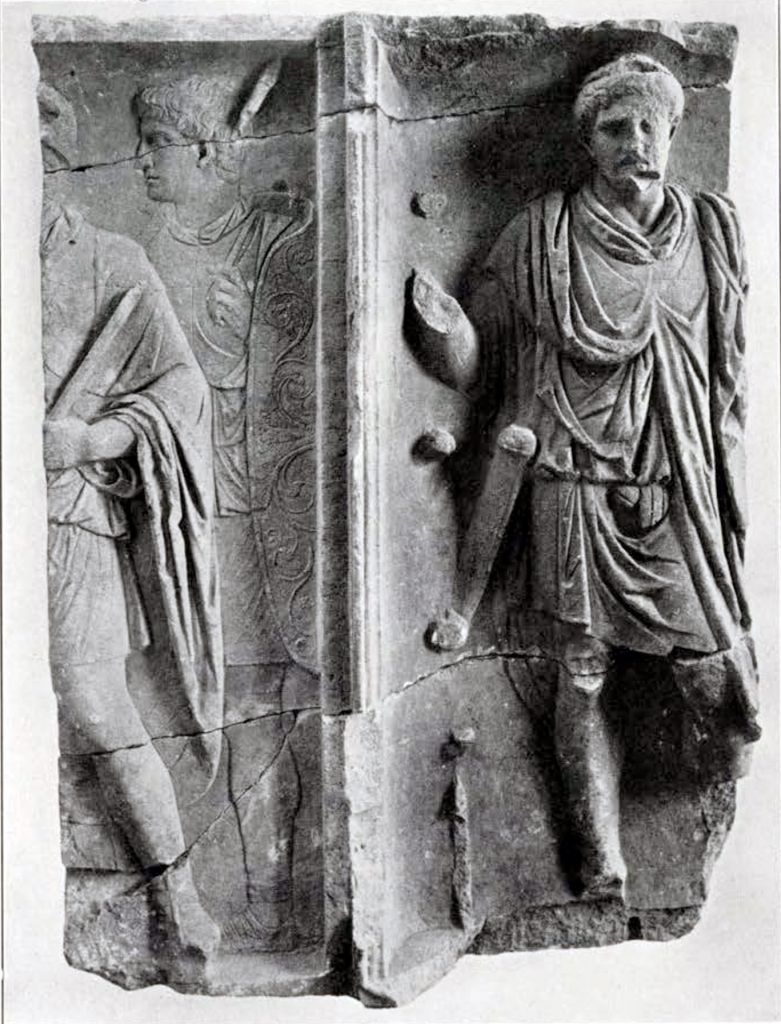

The relief (Fig. 125), which was purchased in 1908 at Pozzuoli by the Director was found the same year about 150 metres southwest of the amphitheatre by workmen engaged in laying the foundations for a modern house. The local proprietor stated that the workmen found in the course of their excavations many blocks of the Roman epoch as well as a road running east and west in the same direction as that of the modern road. Still deeper down was found a second road, again running east and west, and, along its northern margin, the fragments of this relief. These meagre facts in regard to the discovery of the marble, together with a brief description of the sculptured figures, were published by the Italian archaeologist Gabrici, in Notizie degli scavi for 1909, p. 212.

The relief is cut on a block of white coarse-grained marble which measures 1.60 by 1.14 metres and is 28 centimetres thick. The lateral margins of the block coincide not with those of the sculptured scene but with the margins of an inscription cut on the other face of the slab, and surrounded by a moulded frame (Fig. 126). This inscription has been carefully chiseled away, but underneath the marks of the chisel may still be traced many strokes of the original letters, so there is a good chance that the inscription may eventually be read at least in part. The first line seems to have contained only the words IMP CAESARI which points to the inscription having been set up in honor of an emperor. The next lines which contained the name of the emperor or other person honored by the decree, have been expunged with particular care. The word PUTEOLANA which is apparent in the line fourth from the end indicates probably that it was the citizens of the town who erected the decree. Not only is the sculptured scene incomplete, but the lateral faces are dressed as if to be attached to other blocks. One of these faces moreover has a hole for a clamp. The upper and lower edges of the block also show holes for dowels, so that an architectural coping must be supposed above and a foundation course below. Apparently the slab came from a balustrade, one face of which was sculptured, the other inscribed.

It is possible to suppose, however, that the inscription and the sculpture are of different dates. That the inscription should be earlier looks unlikely in view of the thickness of the block of stone on which it is cut. More plausible is the supposition that the inscription is of later date than the sculptured slab and that he who erected the inscribed decree made use of a block already used before in a sculptured monument. In such case he either used a sculptured block of the shape and size that came to hand or he cut from the sculptured frieze a block to suit his purposes. According to the former of these suppositions, the sculptor who carved the frieze chose to have the joints of his blocks fail within the field of the sculptured figures. But this is improbable; the moulded frame which separates the two panels would have been the natural place for the joints to come had not the arrangement of the blocks_ been determined by the needs of the inscription on the other face. According to the alternative supposition, the careful dressing of the lateral surfaces of the block remains without an explanation. One of these surfaces where the relief is lower has received what in Greek architecture is called anathyrosis, a treatment designed to produce a very close joint on the sculptured surface of the slab. On the whole, therefore, it seems more satisfactory to suppose the inscription and the sculptured scene to be of one date and to have adorned the two faces of a balustrade.

Museum Object Number: MS4916A

Image Number: 3325, 183071

In turning to the sculptured figures, the difference in the height of the relief is at once noticeable. The figure on the right projects considerably further from the background than do either of the figures in the panel on the left. It is noteworthy also that the frame which surrounds the panel on the right is much deeper than that on the left unless we are to believe that the frame of the latter panel was applied instead of being cut from the stone itself.

A similar variation of technique may be noted of the mouldings of the inscribed face.

In both panels are represented Roman soldiers. Those on the left are walking toward their right, their gaze seemingly directed toward some object or personage ahead of them. By two devices the sculptor has attempted to throw into the background the second of these figures: first by carving it in very low relief and secondly by making a spear, now broken away, which the other soldier carries, fall directly across the field occupied by this figure. This spear was almost entirely undercut so that it cast a strong shadow on the figure behind. Neither of these devices has met with the entire approval of the more sober critics, for in the first place it is doubtful if the effect of distance is really achieved by such simple expedients and in the second place it is by no means certain that it is an advantage to represent distance in relief. Another noteworthy point about the technique of this panel is that the sculptor was evidently embarrassed by the difficulties of rendering a three-quarters view in low relief. Although the body is represented in three-quarters view, the feet and head are both shown strictly in profile. The figure in high relief in the other panel is represented full face and appears to be walking out of his deep frame directly toward the spectator. The spear which he carried is now broken away.

All three of these Roman soldiers wear tunics (tunica), cloaks (sagum), and have on their feet sandals (calcei). The figure on the right wears a military belt (cingulum militare), from which is suspended a richly ornamented scabbard. But the most interesting feature about the military equipment of these soldiers is the large shield (scutum), carried by the soldier in low relief. Not only is its embossed decoration, which includes floral motives and a scorpion in the center, a charming bit of Roman decorative art, but the method by which the shield is carried is entirely unusual. The first finger of the left hand is passed through a leather loop attached to the central part of the shield. Gabrici, who discusses this interesting feature and cites by way of explanation a passage from Polybius in regard to methods of carrying shields, is not sure whether or no the entire weight of the shield was born by this strap.

The date to which this monument should be assigned probably falls within the second century A. D. Visitors to the Museum will notice several points of technique which it has in common with the reliefs from the arch of Trajan at Beneventum, the casts of which are now temporarily placed at the head of the main stairway. In both monuments variations in the height of relief are employed to represent perspective, and in both, lances cross the field and intercept the view of the figures nearer the background. Both such devices doubtless remained long in vogue, so that there is no valid reason for holding that this relief should be assigned to the period immediately following the reign of Trajan.

E. H. H.