In 1897, through the generosity of Mr. John Wanamaker, the Museum secured two boxes of fragments of antique vases which had been excavated from tombs at Orvieto. The two black-figured amphora portraying the birth of Athena, which were described in a recent number of the MUSEUM JOURNAL, and a number of other vases were put together from this collection of fragments, but the rest of the pieces had, until April, 1913, been subjected to no thoroughgoing examination. It was then decided to undertake to sort the various types of vases represented by these fragments and to ascertain the possibility of restoring any of them.

Museum Object Number: MS4831

The first task was to separate coarse fabrics native to Italian soil from the finer products of Attic ceramic art. This done, there remained hundreds of fragments, mostly of black-figured vases of the sixth century B. C. Of these, the pieces of large, heavy amphorae and hydriae were readily distinguishable from parts of cups, bowls, and lids of lighter clay. After this preliminary sorting according to kind and size began the work of piecing together the pictured scenes represented on these vases, a task which required weeks of work inasmuch as most of the fragments measured no more than an inch in greatest dimension. The results, however, justified the undertaking. Although not a single vase could be restored with no parts lacking, as many as twenty could be set up with such a measure of completeness as to give a satisfactory idea of the original. On all of these scenes are portrayed, that prove to be sufficiently complete to admit, at least in most cases, of full identification. A description of the more important of these vases follows.

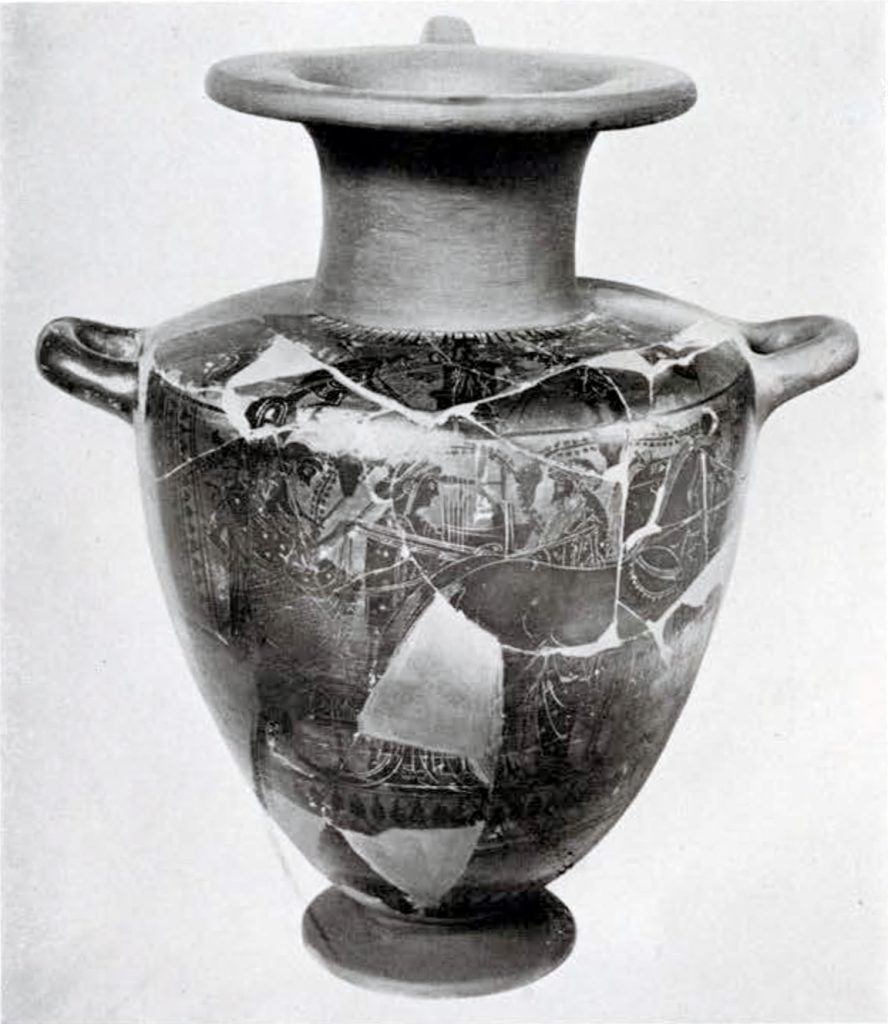

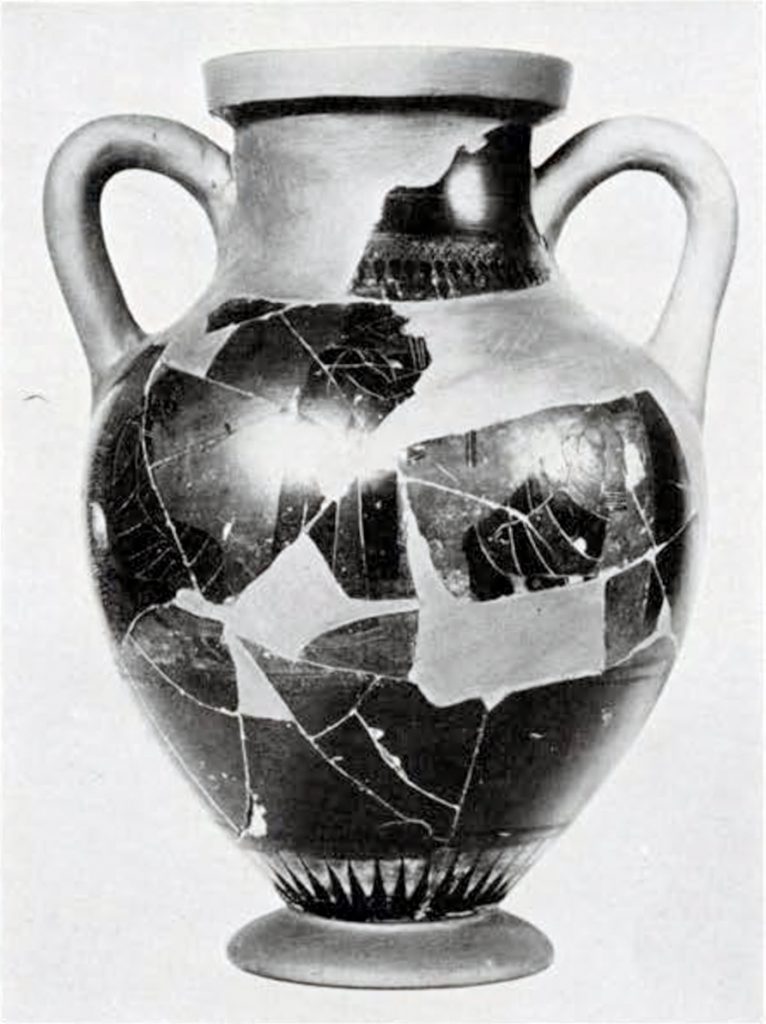

1. Hydria of the black-figured style, height 15¾ in. (Fig. 127). Two painted scenes usually adorn these water-jars, one large one on the side opposite the pour-handle, and a smaller one on the shoulder. The larger scene in the case of this vase represents Athena mounting her chariot. She wears a high helmet and heraegis, the snaky border of which is visible behind her shoulder. Mounting beside her is an attendant armed with sword and spear. Her escort consists of Apollo carrying a lyre and of Dionysos, whose presence is declared by the leafy fronds of ivy which serve as well to frame the upper part of the scene. The smaller painting on the shoulder is a stereotyped rendering of a familiar theme, that of two warriors playing at draughts in the presence of Athena. The artist not understanding the significance of the group he was copying, made the mistake of drawing Athena in front of the gaming-board instead of behind it. The scene is bordered on either side by the armor which the heroes have discarded while indulging in the game.

Museum Object Number: MS4832

Image Number: 2772

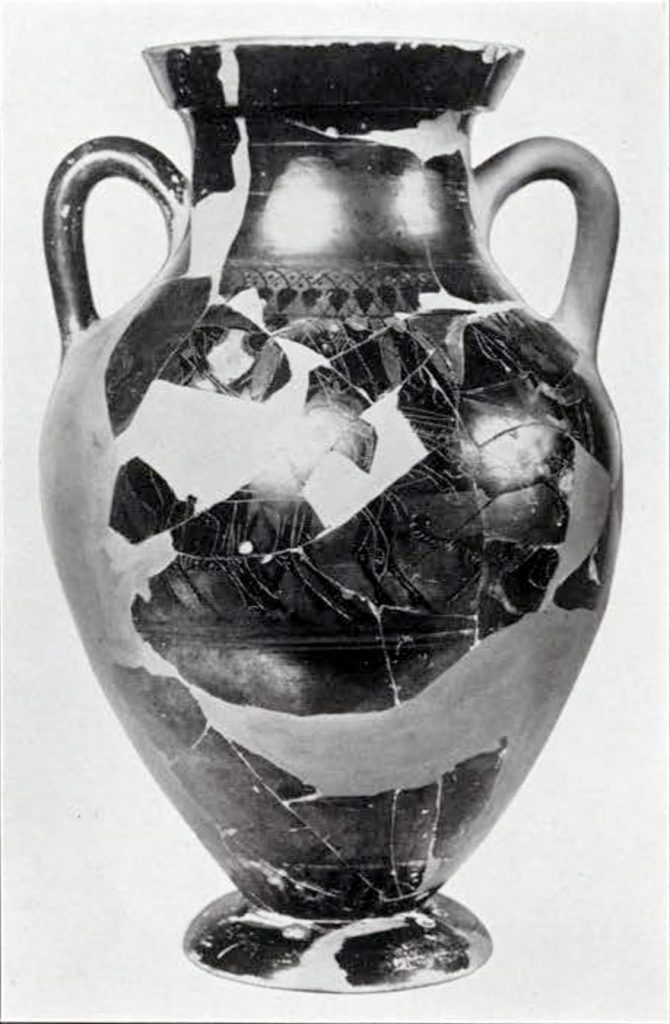

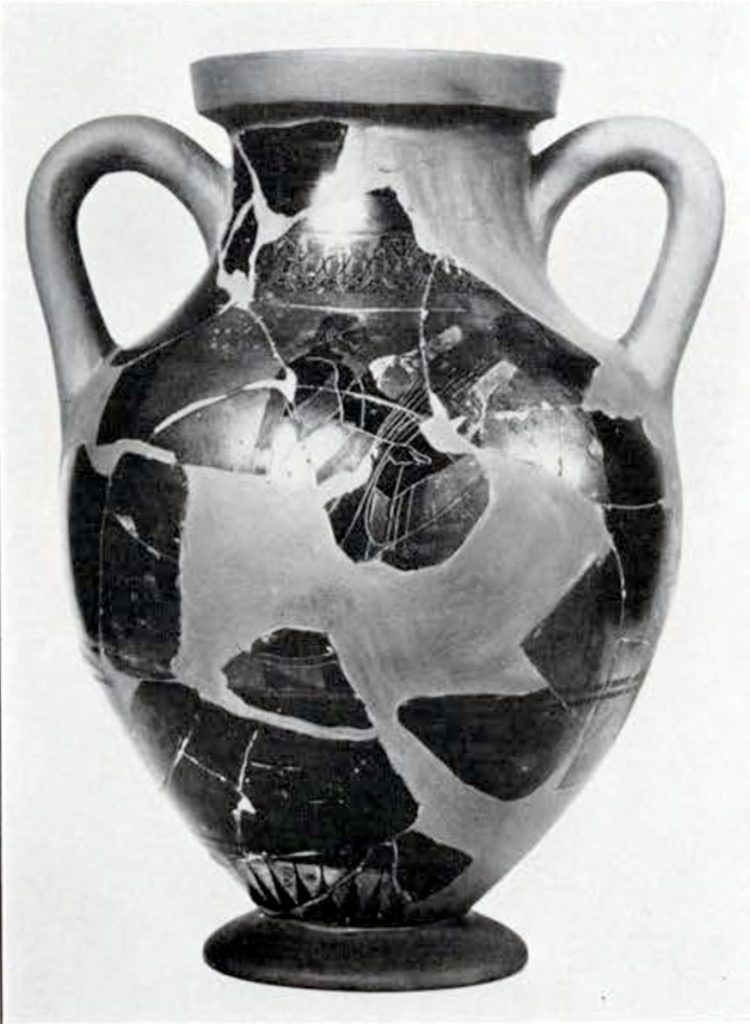

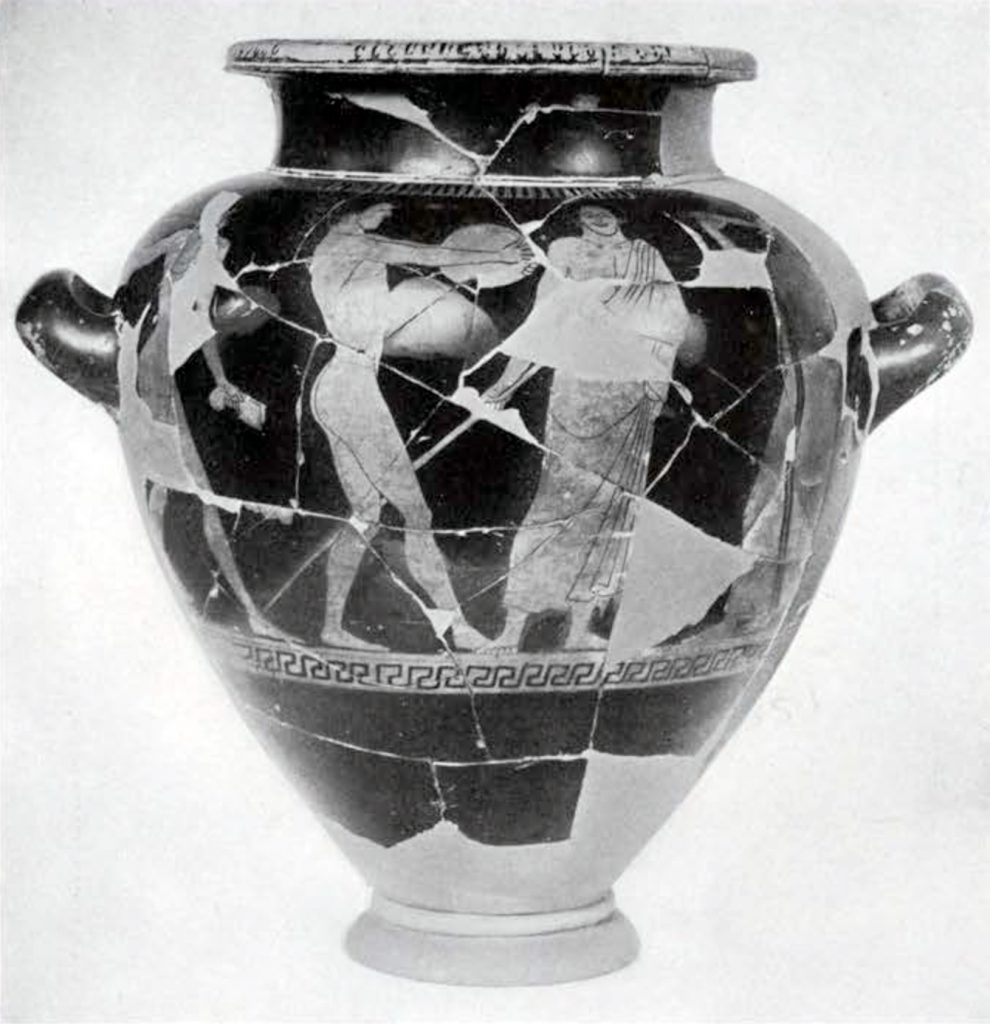

2. Black-figured amphora, height 16 in. (Fig. 128). The scene on the obverse represents a four-horse chariot in motion. It is a lively scene and well drawn. The driver bends forward to his task, a dog runs before and an Amazon who escorts the group looks backward over her shoulder toward the prancing horses. But the most interesting thing about the scene is that the artist has here attempted to render a three-quarters view of a chariot. Ordinarily vase-painters of the black-figured period represented a chariot strictly in profile as on the hydria just described; identity or confusion of contour they avoided by the simple device of placing one horse slightly ahead of another. Or, more rarely, Greek artists drew a full-faced view of a quadriga. The three-quarters view, though frequent enough in later stages of vase-painting, is rare at this early period. The originality of the artist is further shown by the scene on the obverse, which once consisted apparently of two standing musicians and two seated listeners. Most of this painting is gone, but luckily the figure of the fluter remains, a figure replete with realistic touches. No conventional musician is here depicted but a highly individualized character, a middle-aged man whose round shoulders and stout figure are but ill concealed beneath the loose white robe he wears. The forward tilt of his body, the upward thrust of his chin, and the position of his fat arms indicate his absorption in his task.

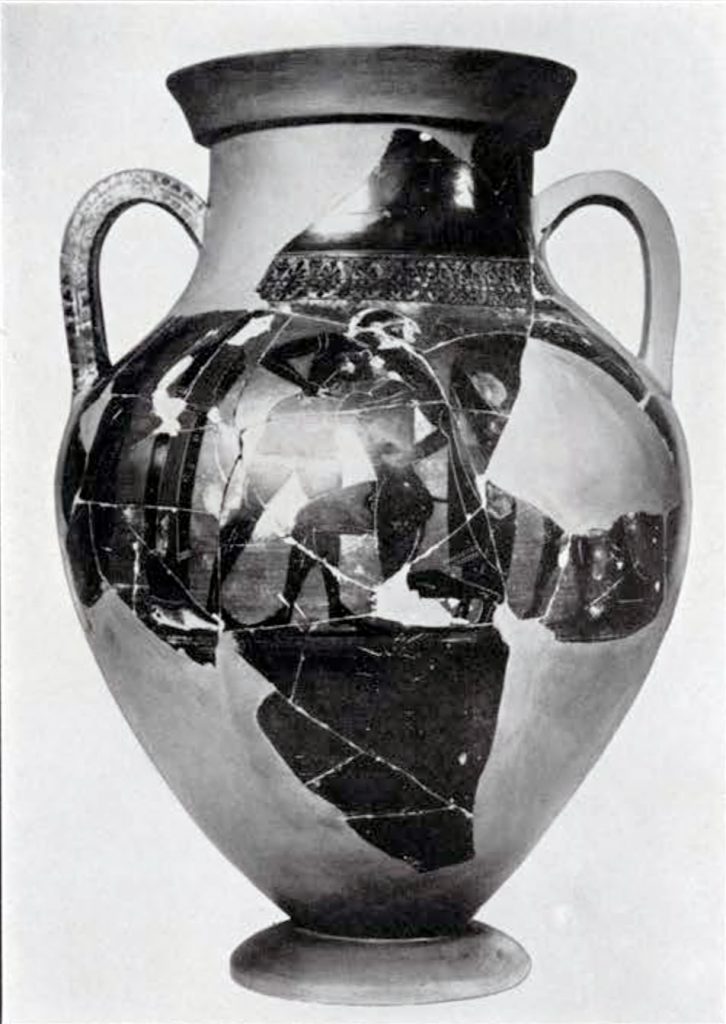

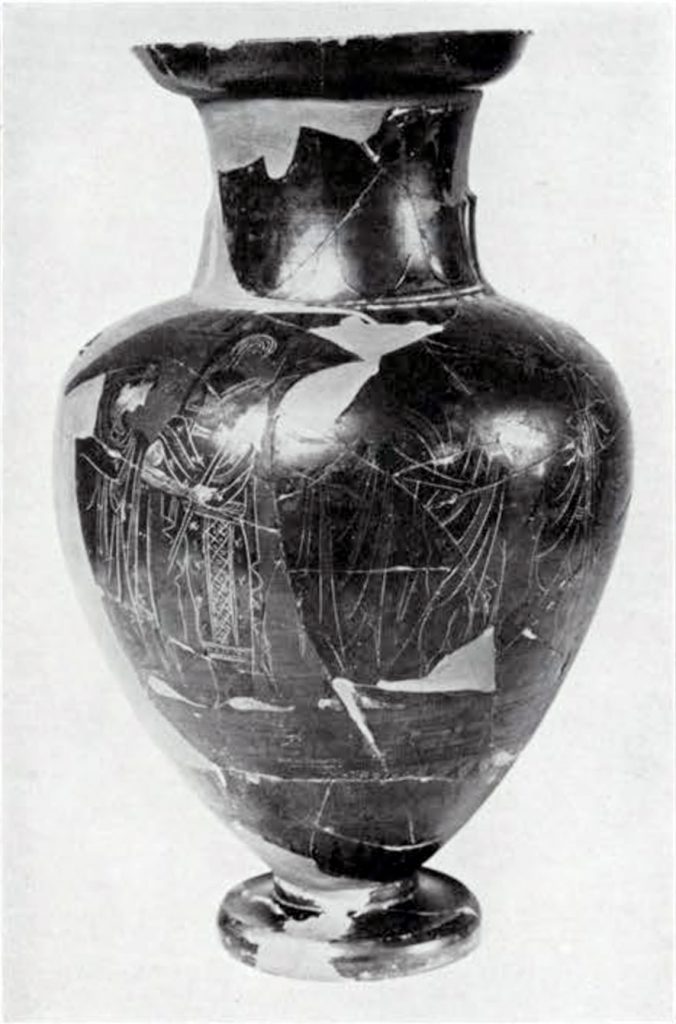

3. Black-figured amphora, height 20¾ in. (Fig. 129). The shape of this amphora is similar to that of the foregoing except for the handles, which are broad and grooved. For this style of amphora the drawing seems unusually archaic. Thus the drapery falls in a few heavy folds nearly parallel one to another; the hair of the woman extends over only the crown of the head, resembling in appearance a flat cap; and the use of purple paint in rendering folds of drapery is abundant. The scene on the reverse is a familiar one, the combat of Theseus with the Minotaur. In the center are the combatants, on the left stands Ariadne; the identity of the other figures is uncertain. The subject of the obverse of this vase is the departure of a warrior in his chariot.

Museum Object Number: MS4833

Image Number: 2774

Museum Object Number: MS4833

Image Number: 2773

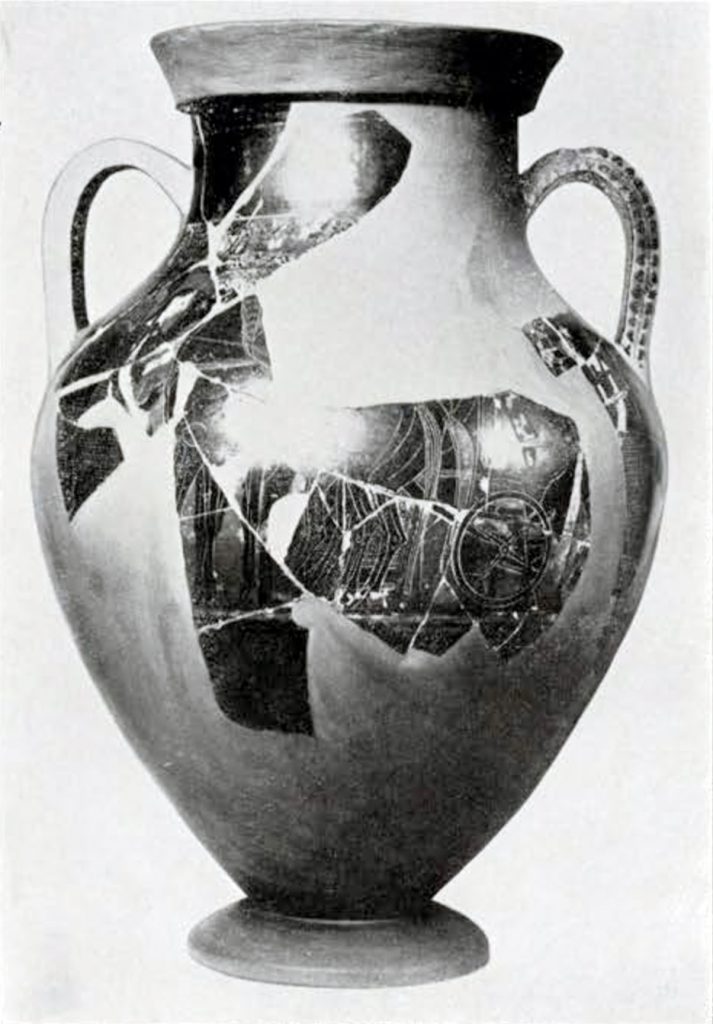

4. Black-figured amphora, height 11 3/4 in. (Fig. 130). Musical scenes are the subject of both the obverse and reverse of this vase. On the one is a single lyrist; on the other a lyrist playing before two seated figures. In the former scene all the details of an ancient lyre are faithfully rendered.

5. Black-figured amphora, height 16½ in. (Fig. 131). This and the next amphora to be described differ from the foregoing in several respects. The shape differs; the shoulder is higher and is sharply differentiated from the neck which is covered with an elaborate lotos and honeysuckle pattern. But the chief difference is that the space between the two decorated panels is not painted black as in the case of the other vases we have noted but is ornamented with an elaborate palmette design. On the obverse of this specimen is depicted Dionysos and a Manad. He holds a kantharos, she castanets. Between them is a goat. On the reverse is Athena and a maiden.

Museum Object Number: MS4841

Image Number: 2781

Museum Object Number: MS4841

Image Number: 2783

6. Black-figured amphora, height 111 in. (Fig. 132). The smaller of the two “red-bodied” amphora is decorated with a scene the more interesting because it departs from the usual types of paintings found on Greek vases. The figures are not all to be easily recognized. Two, however, present no difficulties. They are Athena, the second from the left, indicated by her helmet and spear, and Hermes, the second from the right. He, although he carries a spear instead of a caduceus, is identified by his big hat (petasos) and winged boots. The two women who follow these deities are distinguished by no attributes. For that reason it is probable that they are nymphs, in which case she who follows Hermes may be Herse whom Hermes loved and carried off, and the other may be Aglauros who, according to Ovid, was turned to stone by Athena for conniving with Hermes in the rape of her sister. This, however, is the late version of the tale; according to earlier writers, Aglauros was the benefactress of Athens and was closely associated with Athena. The figure on the extreme right may perhaps be identified as Kekrops, the father of the sisters, for Greek vase-paintings sometimes represent him as a witness of Hermes’ violence. But such identifications are hazardous, especially in this scene where the action itself is suppressed and the actors are merely juxtaposed. On the reverse are four meaningless figures whose only function is to fill space.

Museum Object Number: MS4834

Image Number: 47070

7. Black-figured amphora in affected style. If more of this vase could have been recovered, it would have been one of the most interesting in the group. Both the neck and shoulder of the vase are decorated with continuous friezes painted in what is known as the affected style in which the human figure is greatly attenuated. Hands and feet are long and slim, and heads are abnormally small in proportion to the height of the figures. In spite of these affectations, the style is marked by delicacy and fineness of execution. The decorative patterns on this class of vases and the subsidiary designs, like the small Pegasos under the handle of this vase, are among the best examples of Attic decorative art.

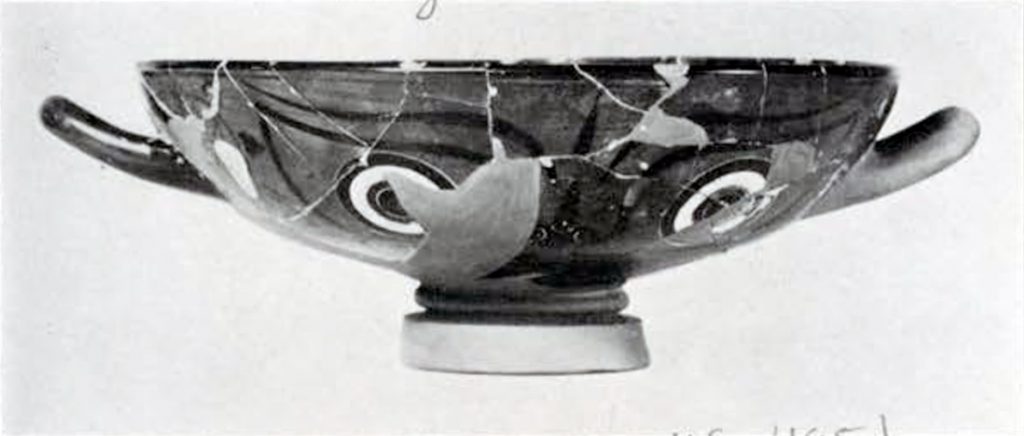

8. Early black-figured kylix, diameter 111 in. (Fig. 133). This beautifully shaped deep bowl is an Attic adaptation of an Ionic type which is thought to have originated in one of the Cyclades. Characteristic are the pairs of eyes, which in primitive art were introduced to avert the evil eye, but in later phases were retained solely for decorative effect. They are separated in our specimen by a highly conventionalized nose, but the conventional ears which frequently frame this design are here supplanted by clusters of grapes, some white, some dark. This bowl belongs to a beautifully executed class of vases so that the possession of even an imperfect specimen is a subject for congratulation.

9. Black-figured lekythos, height 8½ in. The subject of the decoration is a usual one, that of a youth mounting a chariot.

Museum Object Number: MS4840A

Image Number: 47071

10. Red-figured kylix, diameter 8 in. (Fig. 134). This kylix is of later date. It differs from the vases heretofore described in that it is red-figured, that is to say, the space between the figures and not the figures themselves is painted black. Details of drawing are rendered in black lines. The painted scene, which is typical of the period, is a scene from everyday life. It represents a youth writing with a stilus upon a folding tablet. Or is he drawing? The position of the hand suits quite as well the latter act, but there is evidence which goes to show that he is writing. On a well-known

kylix in Berlin is painted a school scene in which among other representations of masters and pupils is that of a young boy standing before a seated master who holds a tablet and stilus in nearly the same position as that depicted here. The boy appears either to be reciting an exercise written on the tablet or to be awaiting the master’s corrections. The position of the two directly opposite to one another precludes the supposition that a drawing lesson is here represented. We are thus warranted in assuming, I believe, that the Museum possesses in this kylix a picture of the Greek method of writing. It is interesting to note by what means the artist has succeeded in adapting this subject to a circular field. He tilts his figure slightly forward and thus contrives both to make the tasselled chlamys protrude into and relieve the empty space on the left, and to bring the cover of the tablet into the middle of the space on the right. The stool on which he sits and the rectangular object, a large part of which is missing, serve further to give a quasi circular contour to the design. Two meaningless inscriptions also are introduced to fill the empty spaces of the picture.

Museum Object Number: MS4851

Image Number: 2786

11. Red-figured stamnos, height 14½ in. (Fig. 135). The interest of this vase is twofold. First, the subject, that of athletes practicing in the presence of their trainers, is interesting in view of the recent revival of Greek athletic sports. The scene takes place in the palaistra or training school, which is indicated by two columns. Next to one of these columns, at the left of the illustration, is a youth holding in one hand a halter or jumping weight and extending his other arm downward. Mr. E. Norman Gardiner, who has made special studies of Greek sports, is of the opinion that the halters were used as dumbbells for separate exercises in a period as early as that of the Persian wars. He suggests that an exercise similar to the one depicted here was invented by the javelin thrower for developing the special muscles and practicing the special positions required for the throw. The next figure is that of a diskos thrower and admirably depicts the first position or stance of this exercise. The athlete stands with his right foot advanced (this position of the feet is commonly reversed in paintings) and holds the diskos with arms outstretched straight before him, his right hand having a slightly higher hold than the left. The trainer with his staff stands directly in front of the athlete and behind him is a figure which plays as prominent a part in scenes of the palaistra as do the trainers. It is that of a musician, a flutist, to whose music the exercises were performed. On the reverse of the vase only the figure of the trainer is at all well preserved. The other point of interest about this vase is the fineness of the drawing. Admirable, for example, is the precision and purity of the line drawing in the torso of the diskos-thrower, the details of which are rendered, some by fine black lines, others by lines of a dull red which is differentiated less sharply from the background of the clay. In strange contrast to the skilful draughtsmanship of this figure is the rendering of the head of the master of the palaistra, which is drawn full face, and which can scarcely be said to excel the crude attempts of a child. Apparently Attic artists were departing from familiar fields when they undertook to draw anything but a profile view. Their earliest attempts in this direction are traced to the period immediately following the Persian wars; in this period faces with grimaces as unlovely as that of our vase begin to make their appearance on what would otherwise be masterpieces of drawing. The general opinion of scholars is that the vase-painters were then influenced by mural designs, notably by the work of Polygnotos, and that the early attempts to render full face views were stimulated by the achievements of the greater art of wall-painting.

Museum Object Number: MS4842

Image Number: 2909

Museum Object Number: MS4872

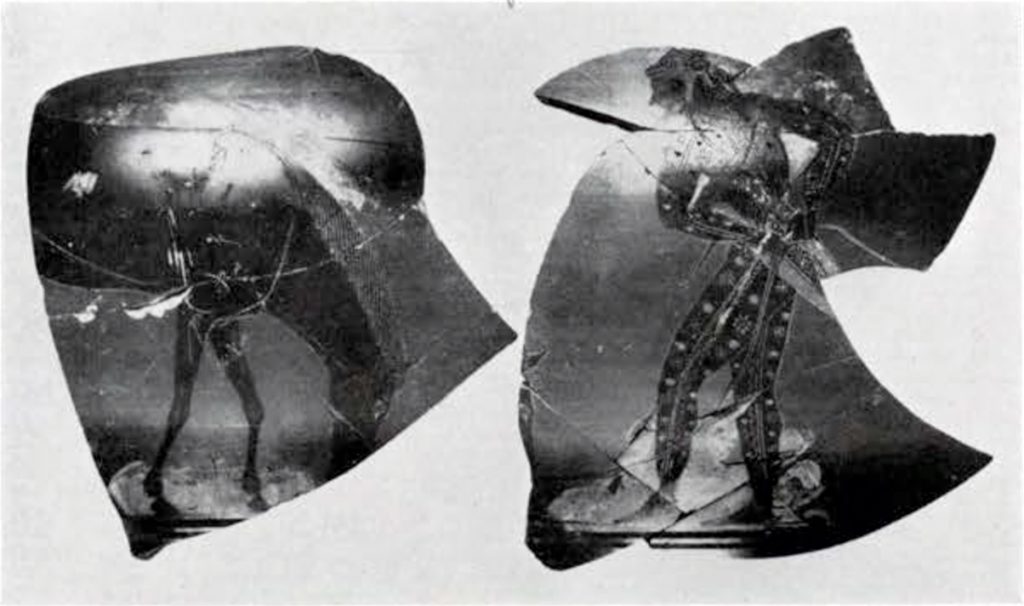

In addition to the vases which could be restored, there were portions of vases which, although too fragmentary to warrant the construction of the whole piece, are yet themselves of great interest. Such is that of Fig. 136 showing an archer in Scythian costume. This figure is complete save for a bit of the quiver and the peak of the cap, and affords an admirable picture of a smart bowman in the Greek army. Of the horse which he is holding, only a portion of the head remains, but a horse from the other side of the vase evidently duplicated this one. The costume of the archer is worthy of notice. Conspicuous are the long trousers or amaxerides which every reader of Xenophon will remember as a characteristic part of Persian dress. Conspicuous too is the peaked cap, the point of which hangs down behind and the ornaments of which, probably of fur, fall in front of the ears. The entire costume, the capm the sleeved shirt, and the long trousers, are covered with geometric figures to imitate the effect of embroidery. It has been generally held that the archers thus clad were themselves Scythians employed in the Greek army, but investigations shown that the Greeks did not organize a corps of Scythian archers until 476 B.C., whereas the black figured vases which portray archers in Scythian attire date from the sixth century. The explanation recently suggested by a French scholar is that Greek nowmen adopted in an early period the costume of Scythians. It was especially affected by the troops who constituted a service auxiliary to the hoplites. It was their place to attack the enemy with arrows before the battle was joined, to aid the hoplites in the thick of the fight, especially by caring for their horses, and in case of victory to help in the pursuit. They were themselves often mounted, so that it is quite appropriate that the archer on this vase should be occupied in holding a grazing horse.

Museum Object Number: MS4873

Image Number: 2797

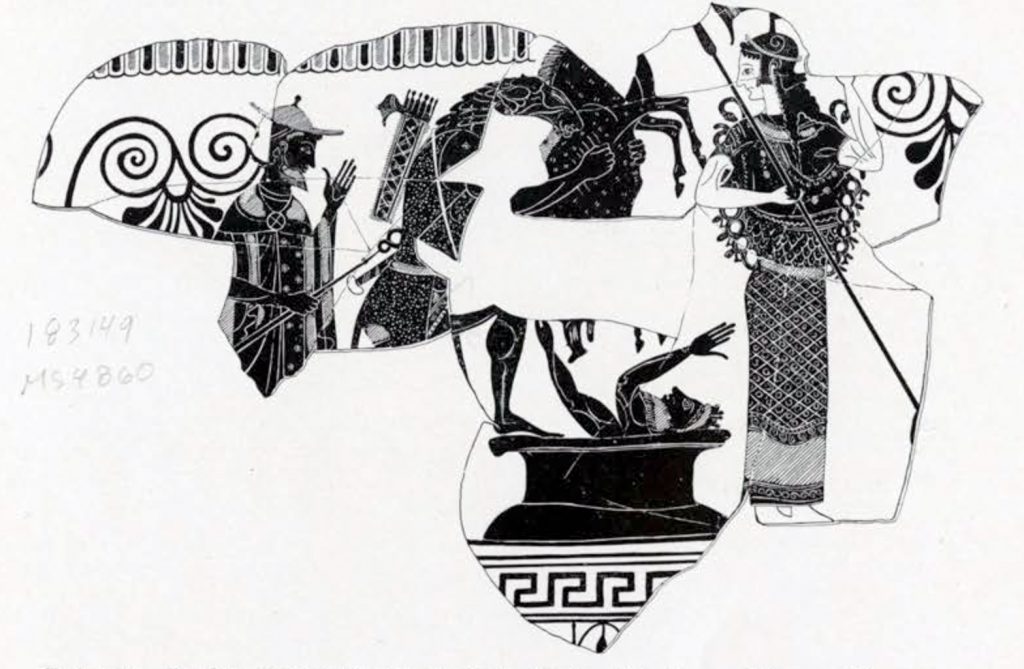

Other fragments worthy of note are those of Fig. 137 in which Herakles is depicted in the act of bringing the Erymanthian boar to Eurystheus, who takes refuge in a wine jar to escape the menaces of the advancing hero. The onlookers of the scene are Hermes at the left, and Athena at the right. The subject is a favorite one with vase-painters.

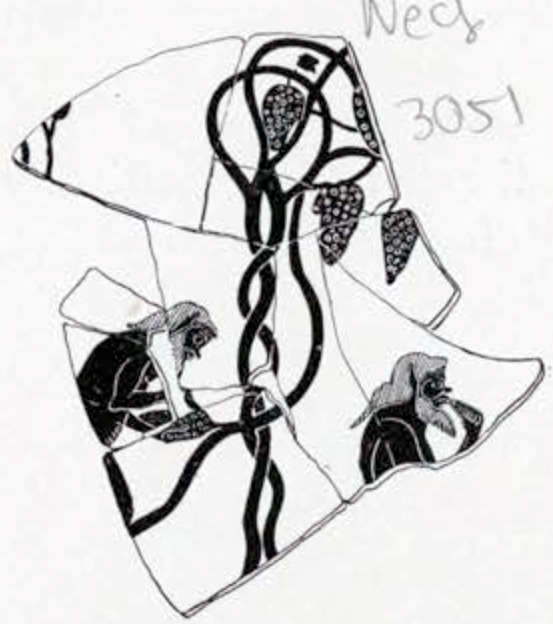

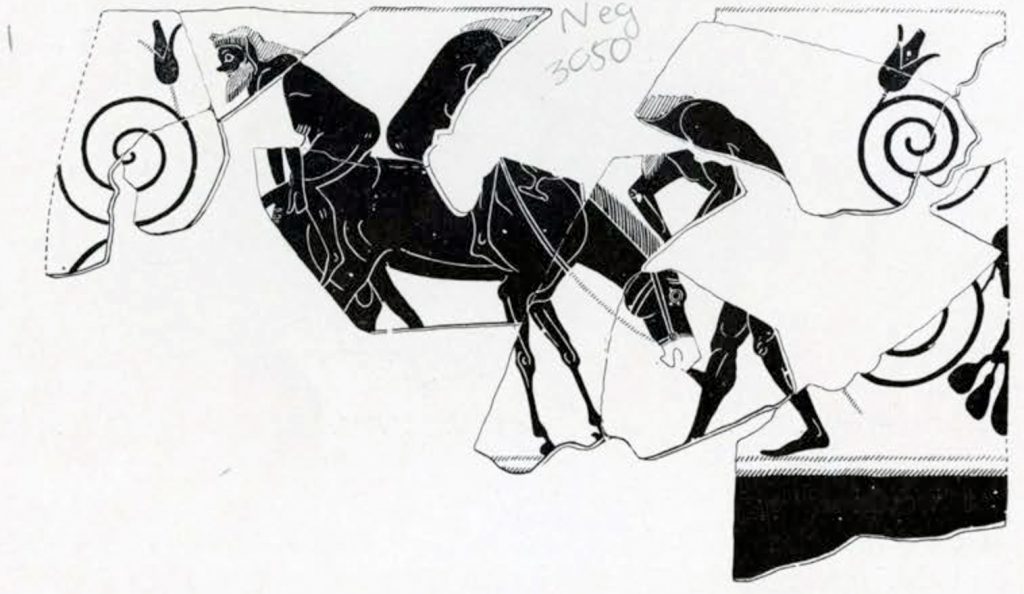

Lastly may be mentioned the fragments of a small black-figured amphora, Figs. 138 and 139, depicting a carousal of satyrs or seileni, the rollicking followers of Dionysos. It is the end of the bout which is represented in Fig. 139. One satyr is helping two drunken comrades home. He has got them safely on a mule, one riding backwards and holding on to the tail, the other, of whom a large portion is lost, holding, it would appear, the bridle and a wine-cup. The anxious friend is jerking up the head of the mule preparatory to starting on the perilous journey. Another portion of the same vase (Fig. 138) shows a charming grape-vine laden with clusters of grapes, from one of which a satyr is eating. His comrade is holding to his mouth an object not easily to be identified. It looks like the head of a pet bird which he is feeding, but conjectures are hazardous in view of the fragmentary condition of the vase.

E. H. H.

Museum Object Number: MS4860

Image Number: 183149

Museum Object Number: 4861

Image Number: 3051

Museum Object Number: MS4861

Image Number: 3050