In the recent history of museum development in America and Europe the accession of collections has been so much more rapid than the construction of buildings to house them that the exhibition rooms in these museums often present the appearance of storerooms, which, in fact, they have become. For this reason the interiors of our museums run the risk of becoming repellent to a great many visitors and thus miss one of the main objects which they are meant to serve, which is to exercise an educational influence by attracting the attention and fixing the interest of visitors. It is not easy to indicate how these difficulties may be overcome, but it is at least possible occasionally to give the public an exhibition which is free from these objections.

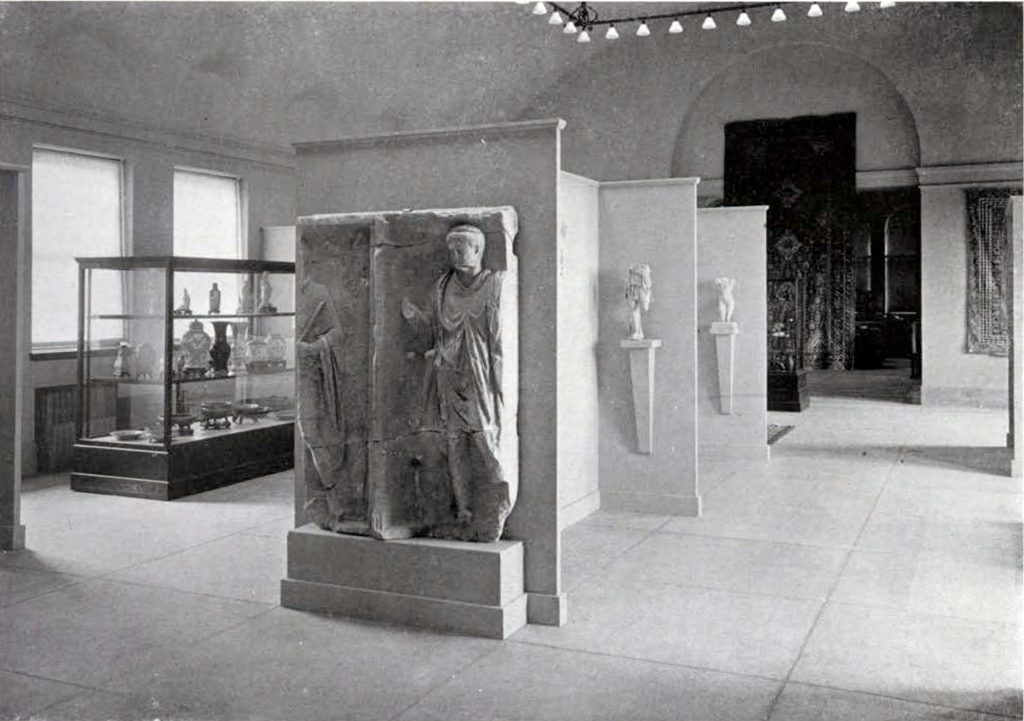

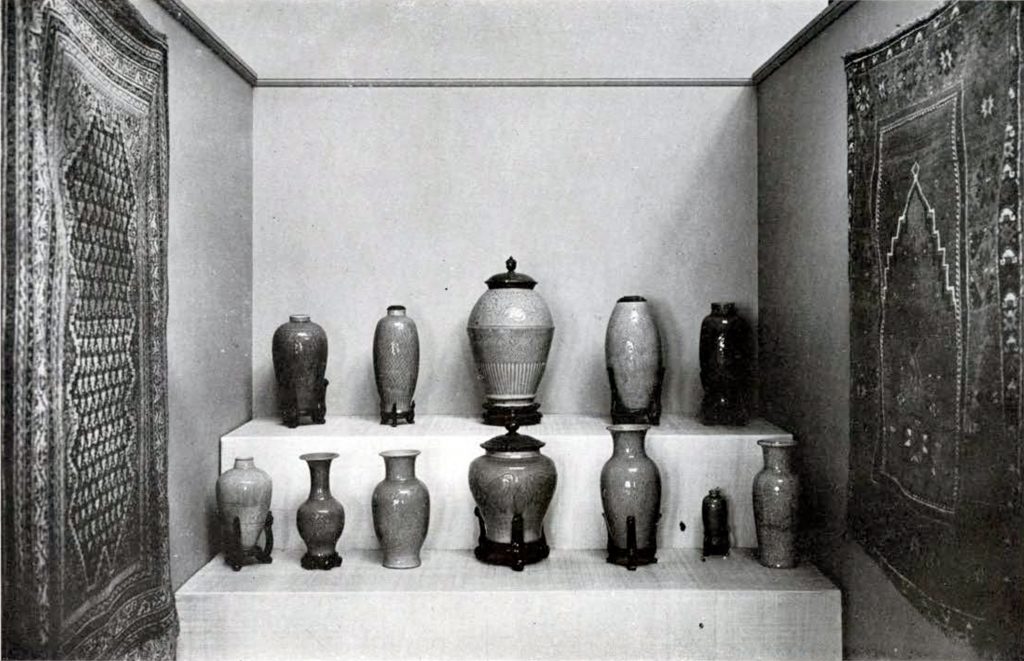

A special exhibition was arranged during the autumn of 1913 and opened on December 12th. It was made up of objects selected from the new accessions, together with some others which either had not been shown or else exhibited under different conditions. The exhibition was also a demonstration of certain desirable methods of museum arrangement. In the first place, the room set apart for the purpose was altered by having wooden screens placed with reference to the adjustment of the lighting, and light gray was uniformly adopted for the color of the entire room, the ceiling being a shade lighter than the walls. The backs of the wall cases also corresponded to this color scheme. In the installation only the best objects were chosen and these were placed in such positions that they could be seen and studied without the distracting effect caused by the proximity of other objects.

Each exhibit, whether a single object or a group of objects, has thus been assigned to its own particular setting, which depends in each case upon its individual requirements. In this way two desirable ends are attained: each object is shown under the best conditions, and in contemplating any unit in the exhibition, the eye and attention of the spectator are concerned with that alone, since other objects do not crowd the field of vision.

The obvious drawback to this kind of arrangement is that it requires too much room, and, therefore, is not applicable to the general problems of museum installation. That it is otherwise the ideal plan can easily be shown by such an experiment as the one I have described. The practical application of such a lesson must of necessity be limited, since no museum can afford to assign so much space to its exhibits generally as this method requires.

It is quite within the power of every museum, however, to have one or two rooms of this kind to illustrate this method of exhibition, to bring into prominence some of its choicest possessions and to afford a pleasant and agreeable feature for those visitors who may find the usual methods of installation irksome or confusing.

Image Number: 1633

The importance of exhibiting collections under the most attractive conditions cannot be overestimated. Visitors to the museum who may have private collections are much more likely to form a plan for presenting them to the museum for the public benefit if they find that the exhibits are arranged in an attractive way.

The considerations which I have brought forward and which I have tried to illustrate are so important and so apposite to our own need for a larger building that I will restate them at the risk of repetition.

A serious drawback to the public usefulness of many great museums is the fact that owing to the lack of adequate space they are overcrowded with the objects installed in them. This crowding of the field of vision with many objects, each of which may in itself be replete with interest, overpowers the mind and produces a sense of helplessness, quickly causing the fatigue which is known to every one who has ever visited a museum for the purpose of seeing its collections.

To the trained student who knows what to look for, this crowding of objects in the exhibitions may not be a very serious disturbance, but to the visitor in general the effect is weariness. To avoid this effect, to make the best use of all available space and at the same time to provide for the demands of scientific treatment, are among the important factors determining the usefulness of a museum.

These factors, combined in the principles of good administration, will gradually become established in their proper relations everywhere, as they become more clearly defined and more generally recognized.

In the meantime, like most museums, we are engaged on the one hand in building up the collections, and on the other hand in trying to meet the obligation which is thereby created, by providing a building to install these collections for the benefit of the people, and to preserve them for the uses of science and education.

G. B. G.