During the last summer the Museum acquired a number of selected pieces of pottery and porcelain from China. The ethnological collections representing past conditions or conditions which are rapidly changing in the Chinese Empire have hitherto stopped short of the decorative arts and have not included any examples of the more artistic products in pottery, porcelain or bronze. The time has arrived when it is no longer easy to procure the objects which correctly illustrate the native culture of China and in a very short time collections of this kind can no longer be procured at all. Any museum which aims to represent human progress in its various lines of development and in its geographical relationships would be seriously impaired in its usefulness and very incomplete in its exhibits if it were unable to include among these, a series illustrating the civilization of China. Among the higher products of that civilization nothing is more distinctive or characteristic than the glazed potteries and especially the porcelains.

Image Number: 4243

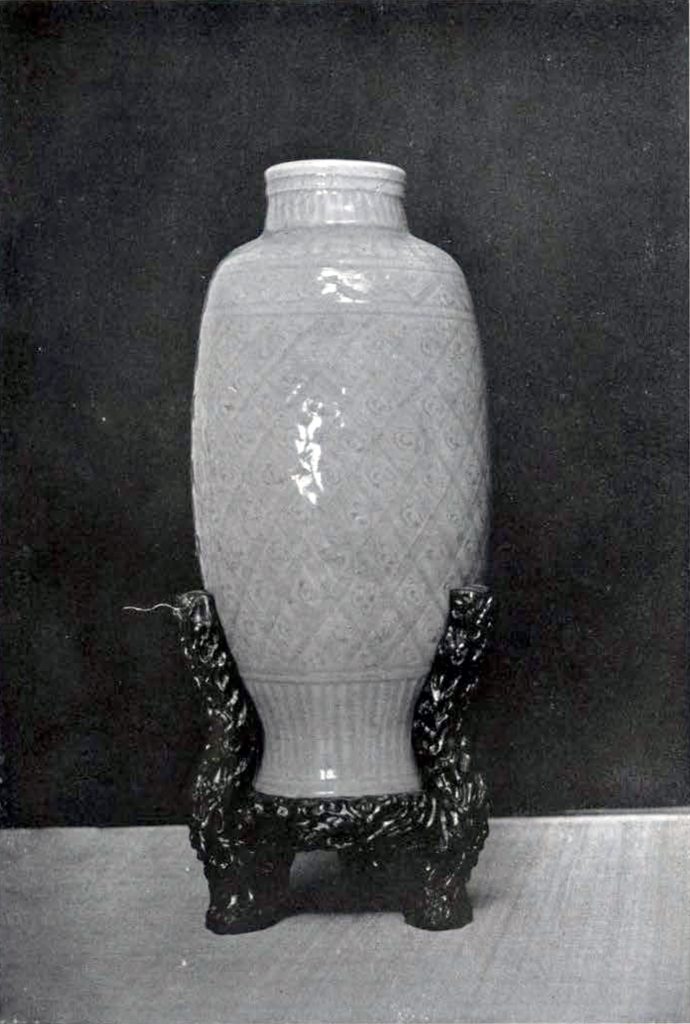

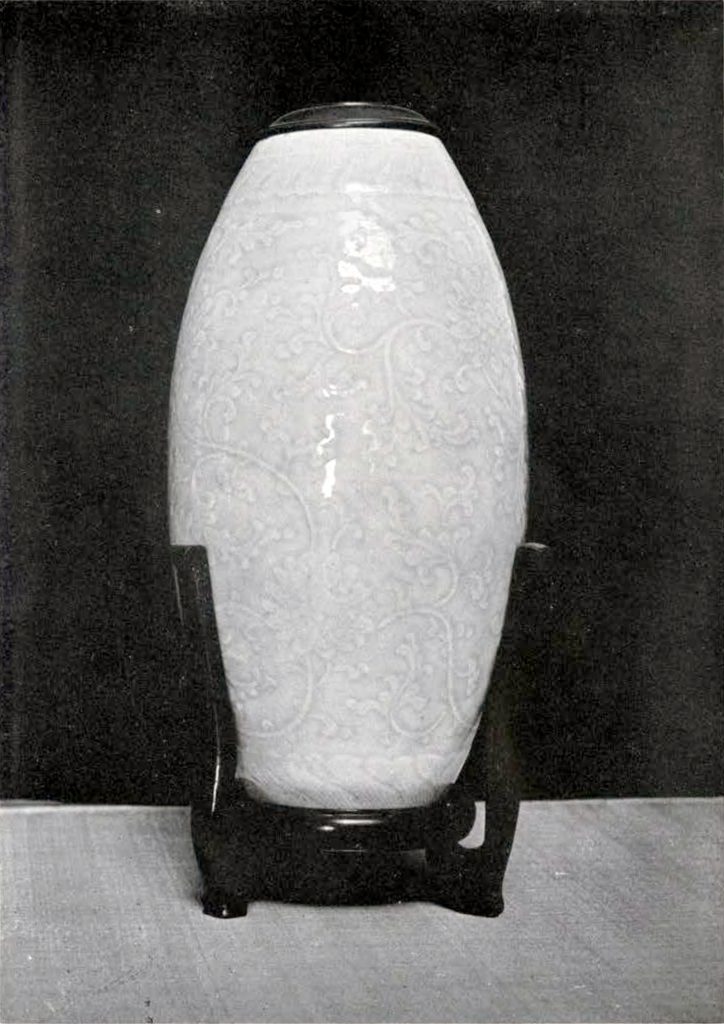

Among the objects recently acquired by the Museum are a number of pieces of the glazed stoneware known to the western world as celadon and to the Chinese as Ch’ing-Tzu, first produced during the dynasty of Sui, A. D. 581-617. Celadon continued to be the most popular ware during the following dynasty which lasted until A. D. 906. Its manufacture went on until the eighteenth century. To the beautiful sea-green pellucid glaze, characteristic of the celadon, this remarkable ware owes its chief attraction. The surface is often relieved by patterns modelled in the pottery under the glaze. These patterns are sometimes floral, with such motives as those furnished by the lotus, and sometimes in conventional diapered lines. Another form of decoration is that which is known as crackle, a mechanical device arising from the technical processes employed in the manufacture of this ware. Such crackle decoration was highly prized by the Chinese according to their own records, and could be varied in intricacy by the skill of the potter.

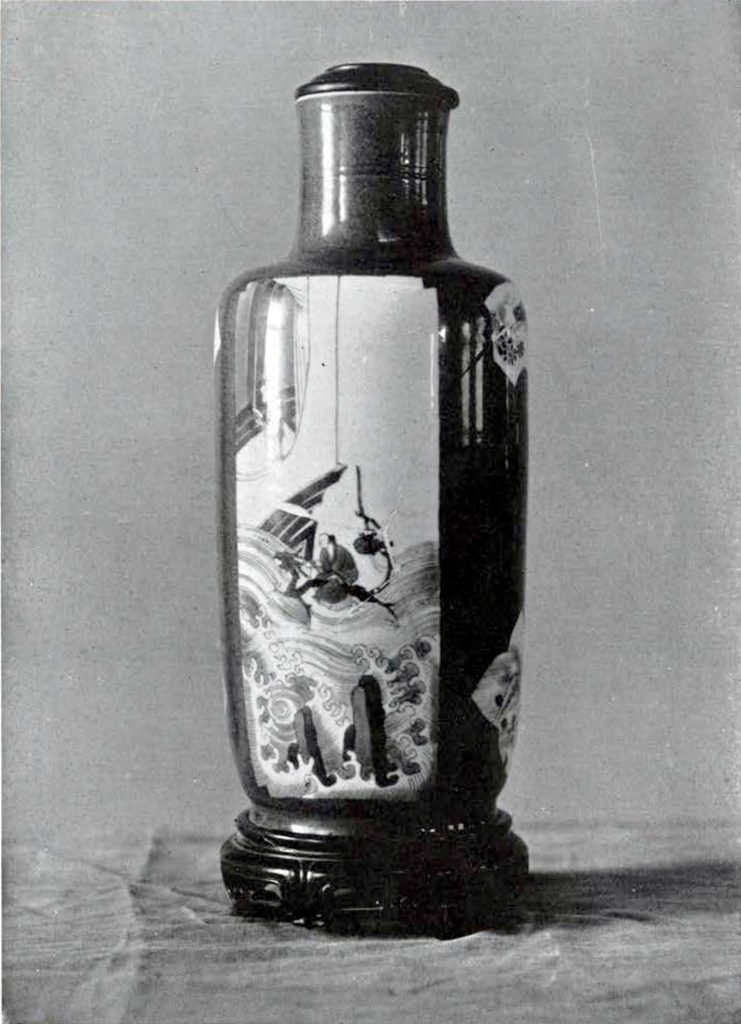

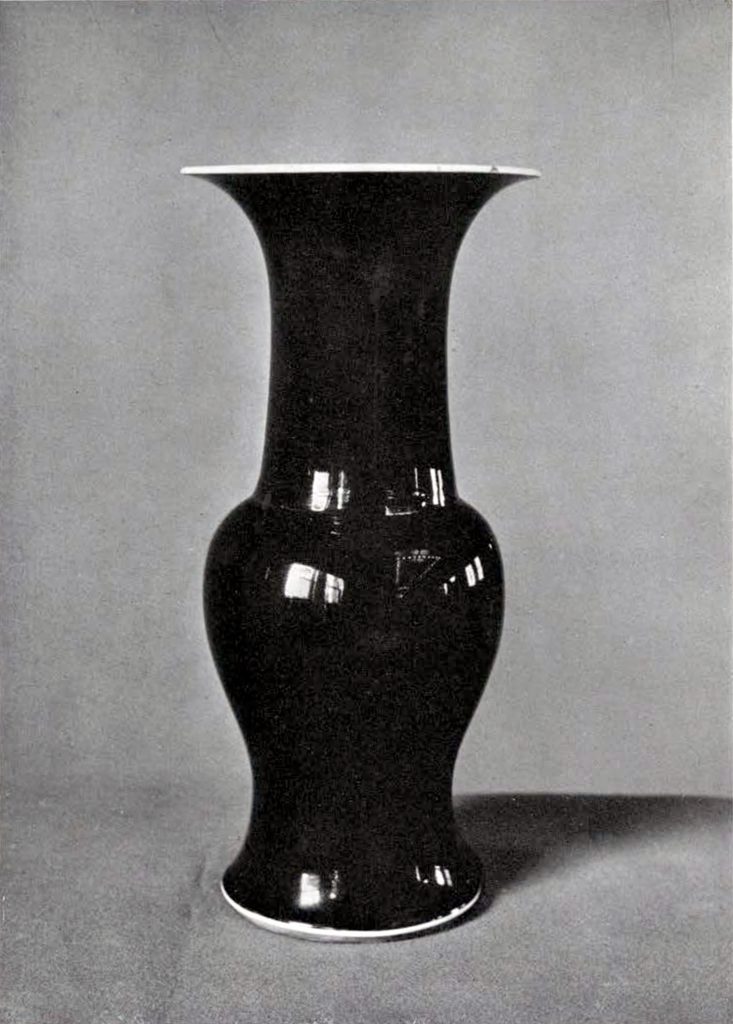

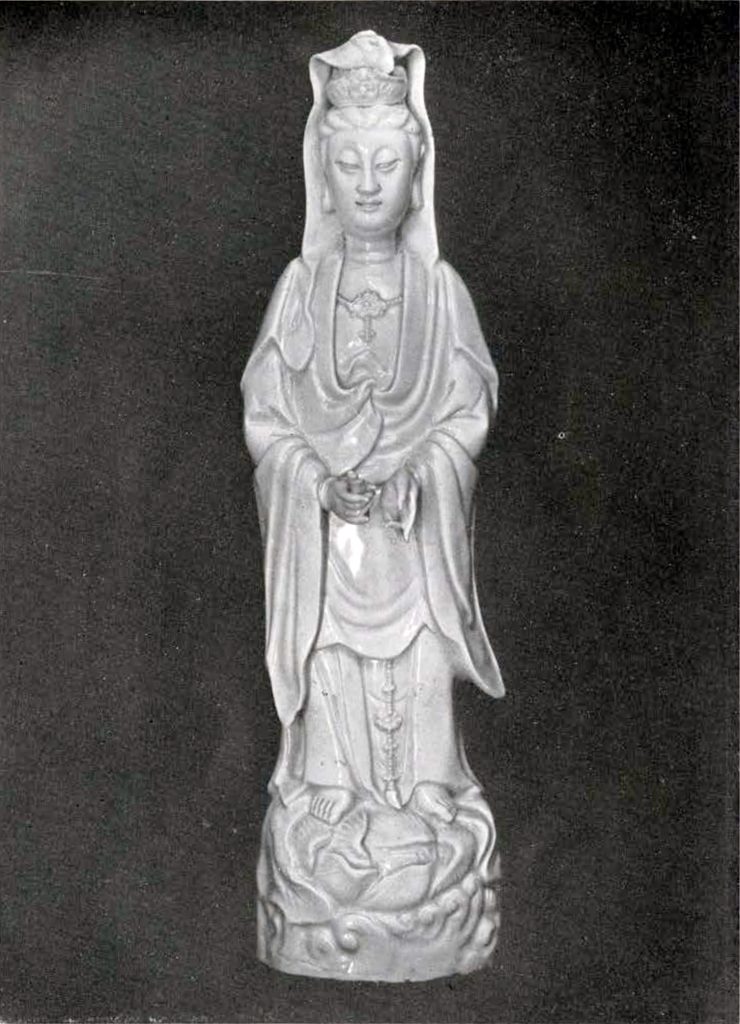

The invention of real porcelain in contradistinction to stoneware is by general consensus of opinion assigned to the Tang Dynasty, A. D. 618-906. The different varieties and the different colors and styles of decoration that we are familiar with in all the great collections which now adorn our western museums and the homes of many collectors, came into existence from time to time during the later dynasties and especially during the Ming Dynasty.

Image Number: 4264

There is a good deal of confusion in the records relative to the production of celadons and porcelains during the earlier periods and it is probable that many of the productions of the Sung Dynasty which were commonly called porcelain, were actually celadons. It was under the Ming Dynasty, 1368-1643, that the manufacture of porcelain really became a well developed industry. During this long dynasty the number of kilns at work and the number of artists and workmen employed must have been very considerable. Many fine polychrome vases were produced to adorn the Imperial palaces and the houses of the nobles. The familiar blue and white ware had its origin about the beginning of this dynasty.

In Europe and America, the interest in Chinese porcelain has grown rapidly during recent years. The artistic qualities displayed and the great variety of design shown have attracted collectors and students of decorative art, many of whom have cultivated a taste for these productions of the oriental designer. Many private and public collections have been built up with the result that the finer wares have become rare and expensive. At the same time, students of the subject have in these collections a wealth of readily available material for study which should do much to advance our knowledge of Chinese art and especially our knowledge of the history of porcelain in China from the tenth to the eighteenth centuries. At the present time our knowledge of the subject is very incomplete.

The group of these characteristic Chinese productions purchased by the Museum forms the starting point from which may be built up a collection of Chinese ceramics that will faithfully represent the technical and artistic qualities of Chinese pottery and porcelain and that will satisfy the demands of students of these oriental fabrics and of all who are interested in the history of art in China.

G. B. G.

Image Number: 10712

Museum Object Number: C40

Image Number: 10719

Museum Object Number: C39

Image Number: 4266