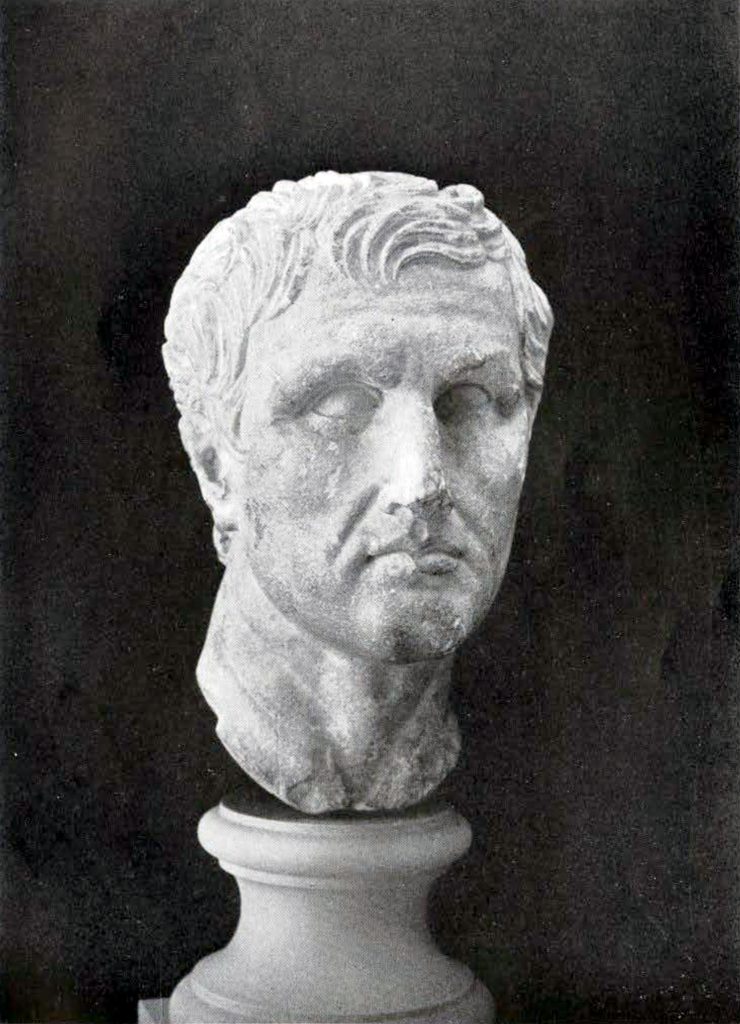

When in 1882 Bernoulli was compiling his publication of Roman portraits, he was able to cite nine examples of a type of head which was then generally regarded as a portrait of Pompey. Before the end of the century the list of known replicas had doubled and the name had been changed from Pompey to Menander. It was Professor Studniczka, of Leipzig, who first associated this type of head with ‘the name of the comic poet His conclusions were based on its resemblance to a likeness of Menander on a relief in the Lateran and that on a marble medallion in Marbury Hall, England. Neither resemblance is striking and the identification is so uncertain as to lead scholars to accept it only tentatively. At least three replicas of this head are now in America: two are in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the one a permanent possession, the other a loan, and the third, reproduced in Fig. 68, has been, since 1901, in the possession of our own Museum.

Museum Object Number: MS4028

According to information which there is no reason to doubt, it was found at Pausola in the Marches. It is somewhat over life-size, measuring fourteen inches in height, and is cut from a fine-grained white marble. The missing parts are the margin of the right ear, the margin and lobe of the left ear, and the end of the nose. There are also scratches on the cheeks and the surface of the marble has suffered somewhat from corrosion. The neck is worked for insertion into a draped statue or a herm.

As with other replicas of this head, the face is beyond doubt a careful study of an individual. The shape of the skull, which is unusually broad at the top, the wrinkled forehead, and sharply characterized mouth with its expression of weariness show that the head was modeled from life. But it is only necessary to compare this head with that of a Roman matron exhibited in the same room and described in the last number of this JOURNAL to show how radically different the two portraits are. The ” Menander” head stands at the beginning of the splendid series of portraits left us by classical art, the head of a Roman matron at the end. The one reflects the artistic traditions of the early Hellenistic period, the other, those of the Roman empire. The former stands in closer relation to idealized types than does the latter; the disordered hair, the deeply set eyes, and noble bearing of the head are characteristic of the heroic types of Hellenistic sculpture. And the expression of the face is more subtly conveyed. Without resort to that unsparing delineation of physical peculiarities which characterizes Roman portraits, the sculptor has given to the face an expression which is both thoughtful and sad, as of one who sees and knows too well the frailties of human nature.

E. H. H.