In response to the universal interest in the recent discoveries in Crete, the Museum has acquired reproductions not only of the more important art objects found in Cretan soil, but also of those from Mycenae and Vapheio which, though found on the mainland, are yet the product of the same pre-Greek civilization which flourished in Crete, if indeed they are not, in many cases, the actual handiwork of Cretan craftsmen. An exhibition of these reproductions has been arranged on the second floor of the Museum.

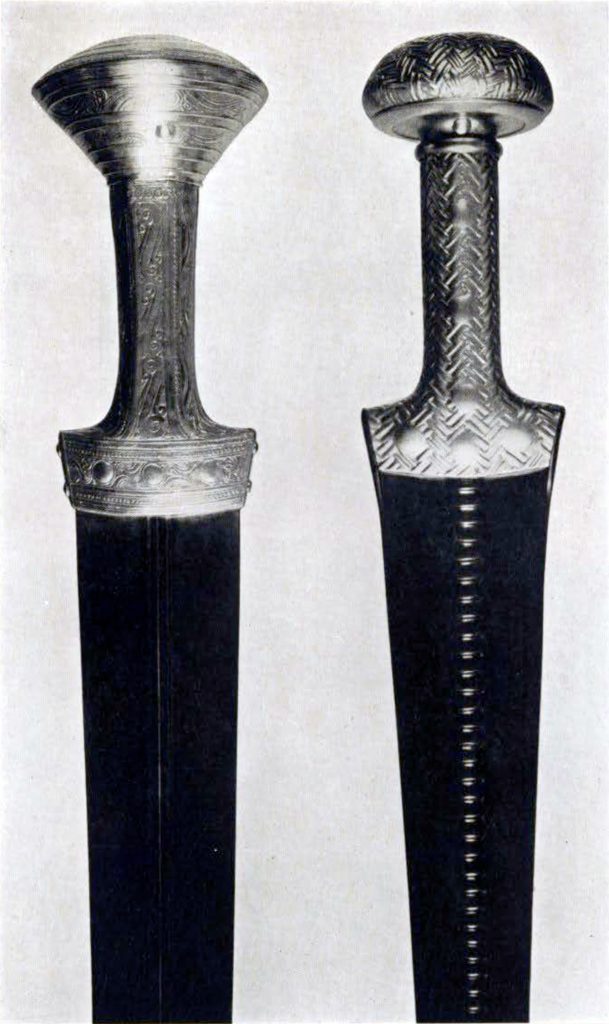

From Crete come frescos, most of the stone vases, and small figurines of faience; the objects from the mainland include gold and silver vases, inlaid daggers, and swords, and a number of frescos from the citadel of Tiryns. These various groups are described in the following pages under their several heads.

Metal Work from Mycenæ And Vapheio

Museum Object Number: MS3985.1

The great majority of metal objects are from the treasure which was recovered by Heinrich Schliemann in the shaft-graves of Mycenae in 1876. They constitute a burial outlay which for splendor and magnificence rivals the wealth of Egyptian tombs.

The reproductions represent the original appearance of the gold treasure rather than its appearance when found, for owing to the fact that the roofing of the graves had collapsed, the gold and silver vessels and the gold masks were crushed and flattened beneath the weight of the fallen beams. The beautiful inlaid work of the blades was so concealed by corrosion that it was not discovered until the blades were cleaned in the National Museum at Athens. But, although these reproductions involve some restoration, they may be regarded as giving an accurate and trustworthy idea of the original appearance of the objects.

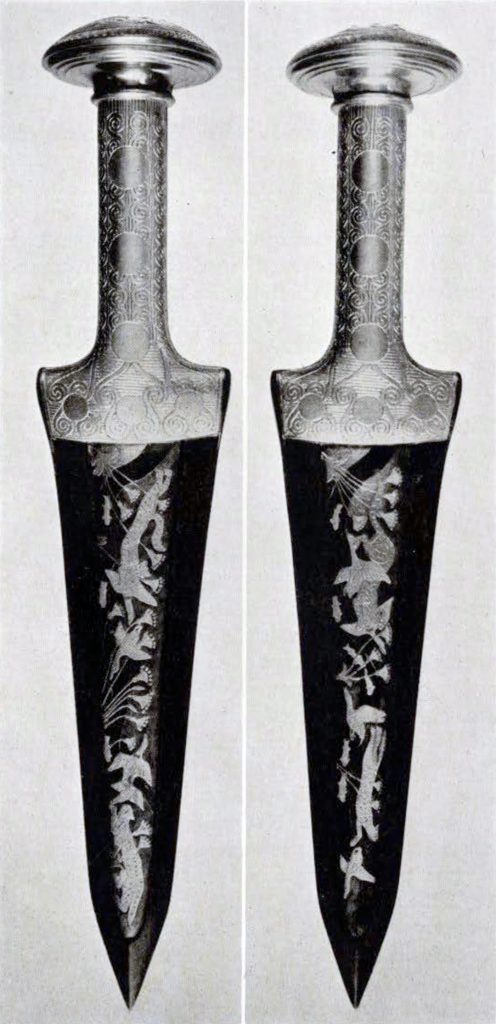

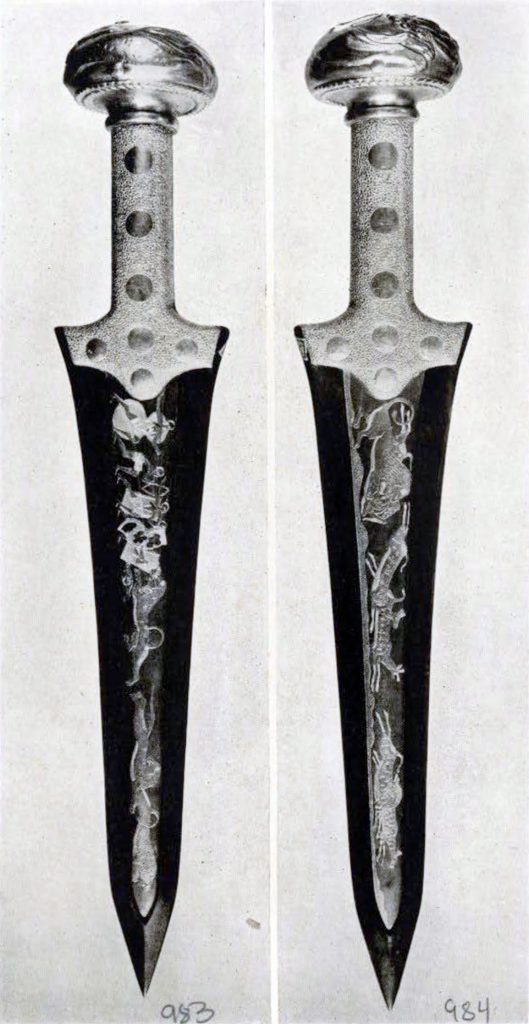

The daggers are inlaid by an elaborate technique indicating the highest skill in metallurgy. On either face of each blade was inserted a strip of alloy which contained iron and silver and which oxidized less than the bronze of the blade itself. The ornamental figures for inlay were cut from sheets of gold alloys of various colors and were hammered cold into the metal field. The fineness of the workmanship is best exemplified in the daggers shown in Figs. 73 and 74. On one is depicted a lion-hunt, on the other the pursuit of ducks by cats along the banks of a winding stream.

The two gold cups found by the Greek archaeologist, M. Tsountas, in a bee-hive tomb at Vapheio near Sparta are probably the finest examples of gold-work which have come down to us from this early period (about 1500 B. C.). A new explanation of the scenes which decorate them has recently been offered. It has been suggested that the reliefs on either cup may be divided into three chapters; that on the cup at the left in Fig. 81 shows three successive stages in the business of decoying a bull; and that on the cup at the right the various vicissitudes of trapping bulls in nets.

The Snake Goddess and Objects Belonging To Her Shrine in the Knossos Palace

Of all the dramatic discoveries made by Sir Arthur Evans on the site of the Knossos palace none surpasses in interest that of the “Temple Repositories.” The story is now old of how Sir Arthur one day noted that the stone floor in a small room west of the central court was slightly depressed. Already two buried chests had been unearthed beneath this floor, but the area affected was outside the limits of these chests. Upon taking up the pavement it was found that the entire floor and the superficial chests already discovered were built above a stratified deposit dark with the fat of sacrifices and crammed with vases and many small objects. It was later apparent that all this deposit was included within two great stone chests sunk beneath the level of an earlier floor. There could be no doubt from the start that the excavator had to do with the treasure of a sanctuary. This was sufficiently shown by the clay sealings which had once fastened the rolls of papyrus or of parchment on which, most probably, the inventories of the sanctuary were kept; the signs on these sealings were many of them of a character known to be sacred.

Museum Object Number: MS3986

Figs. 2 and 83 show reproductions recently acquired by the Museum o the small objects is recovered from the fatty earth of these two heavily-built stone chests. The center of interest in this group is the trim little figure of the snake-goddess worshiped at this sanctuary. She is clad a costume astonishingly modern which consist of a bodice cut very low in front, a richly embroidered bolero jacket, and a skirt with an apron panier. Entwined about her arms and waist and surmounting her high tiara are spotted snakes, the symbols, apparently, of an earth-goddess. This figure, Like the great majority of the small objects from the shrine, is made of a faience which is thought to be of local manufacture.

Scarcely second in interest to the goddess herself is a figure usually called a votary who holds two snakes in her extended arms. The costume which she wears shows some variations on that of the goddess, but may be taken to represent merely another style in vogue in Crete at the time that these figures were made in the seventeenth century B. C. Still other fashions are recorded in the votive robes offered at this shrine. Two of these have front breadths, aptly likened to Watteau panels, which are embroidered with clumps of crocuses.

Of the other objects from this shrine some are to be regarded as votive offerings, others as ornaments. Bushels of shells were found, the majority of which were cockle-shells artificially tinted. These had apparently served to decorate the floor of the shrine, and it may be that the floor was also covered with a faience mosaic imitating the life of the sea, for flying-fish of faience and shells were found as well as bits of the “rock-work” pattern used to frame marine pictures. Small faience cups ornamented with sprays of leaves and little stone tables of offerings bore witness to the fact that offerings were actually made at this shrine. Three other objects are worthy of special notice. One of these is a marble cross of orthodox Greek shape. Whether it occupied a conspicuous position in the shrine is not known, but that the cross had some religious significance in this early period is at least probable. The other two are reliefs, restored from small fragments, representing respectively a cow and a goat suckling their young. They are represented with the same admirable vigor and liveliness that characterize the modeling of the figures of the goddess and her votary.

Paintings From Ægean Palaces

The civilized world will never cease to mourn the loss of the paintings of classical Greece. That there is no picture of Polygnotos as there is a statue of Praxiteles, a tragedy of Sophocles, and a building of Iktinos, is a heavy curtailment of our heritage from antiquity. Strangely enough, the hand of time which has robbed us of the pictures of the great classical painters has restored to us the works of the artists who preceded them by a thousand years. The famous pictures of the Pinakotheke on the Acropolis and of the Club-house of the Knidians at Delphi are gone forever, but those that adorned the walls of Ægean palaces remain. We know more, in fact, of painting in 1500 B. C. than in 500 B. C.

Museum Object Numbers: MS5297 / MS5300

It is only in recent years that this knowledge has been acquired and it is in Crete that the largest number of frescos has been found. On the south coast of the island near the place where St. Paul was shipwrecked is a villa which dates from about 1700-1500 B. C. Here several beautiful mural paintings were recovered by the Italian scholars, but the most prolific source for mural paintings, as for every other prehistoric antiquity, is the palace at Knossos, Crete. The story of this palace now needs no repetition ; this fabled home of Minos and the Minotaur has been stripped of its secrets and shown for what it is, a maze of store-rooms, winding corridors, little sanctuaries, work-rooms, and private suites, all grouped around courts open to the sky, and equipped in a fashion thoroughly modern.

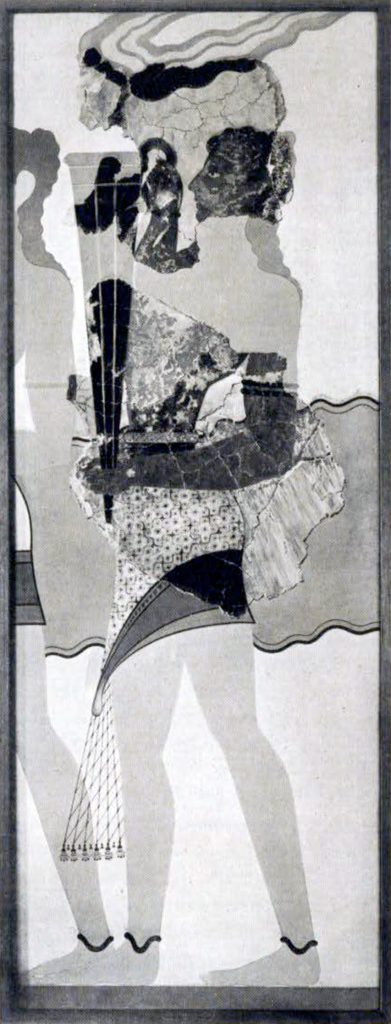

As to the life which went on in this palace the painted frescos provide a useful commentary. The Museum has recently purchased a set of reproductions of these frescos by the veteran Swiss artist, M. Gillièron, whose skilful hand has been at the service of archaeologists since the days of Heinrich Schliemann. Many of these frescos are as yet little known, so that a brief description of them may be in place here. They date with one or two exceptions from the last period of the Knossos palace in which the majority of the rooms were renovated subsequent to a conflagration or some other disaster. The date to which they are to be assigned is approximately 1500 B.C. They are painted in true fresco while the plaster was still wet; in one or two instances the figures are modeled as well as painted.

Museum Object Numbers: MS5299 / MS5301

Image Number: 2682

There were two entrances to the Knossos palace, a state entrance on the north where foreign envoys and people of note were ushered in, and an entrance on the southwest which, it is thought, was used by traders and for domestic purposes. From the glare of an open court that on busy days must have been thronged with waiting merchants and their wares one entered the palace through a portico and a corridor the walls of which were adorned with the fresco. A procession is here depicted in which both men and women figure. The lower part of the picture was still adhering to the wall and portions of the upper part were found lying face down on the floor of the corridor. The subject of the procession recalls the processions of tribute-bearers on the tombs of Egyptian kings and it has been suggested that this corridor, so near the place where business was transacted, might well be decorated with a painting portraying the men who paid tribute to the lord of the palace. However that may be, this picture and the fresco of the cup-bearer from a corridor parallel to this are of the utmost importance for the light they throw both on the racial type and on the costumes of this long-forgotten and brilliant people who lived in Greece before the Greeks. Their waists, according to convention, are exceedingly small and are tightly drawn in by silver-mounted belts, from which, in the larger picture, hang pendants of beadwork. The type of face as shown in the fresco of the cup-bearer is almost classical, and in general these “cup-bearing youths” carry themselves with a dignity and pride that belong to a ruling race.

The same impression of manly vigor is given by the painted relief of a king which decorated an upper gallery overlooking on the south the great central court. The fleur-de-lys motive plays an important part in this fresco. The crown is made of fleur-de-lys with a peacock’s plume in the center; a collar of the same ornament is worn about the neck, and the motive recurs in the landscape background. Because a goddess and her attendant on a well-known Mycenaen ring wear ornaments of lilies in their hair, and because, in general, the lily is associated with sacred emblems, it is thought that the personage here represented is either a priest or a king. The figure is executed in low relief and shows a style of modeling extraordinarily advanced.

Museum Object Number: MS5304

Museum Object Number: MS5307

Museum Object Number: MS5310

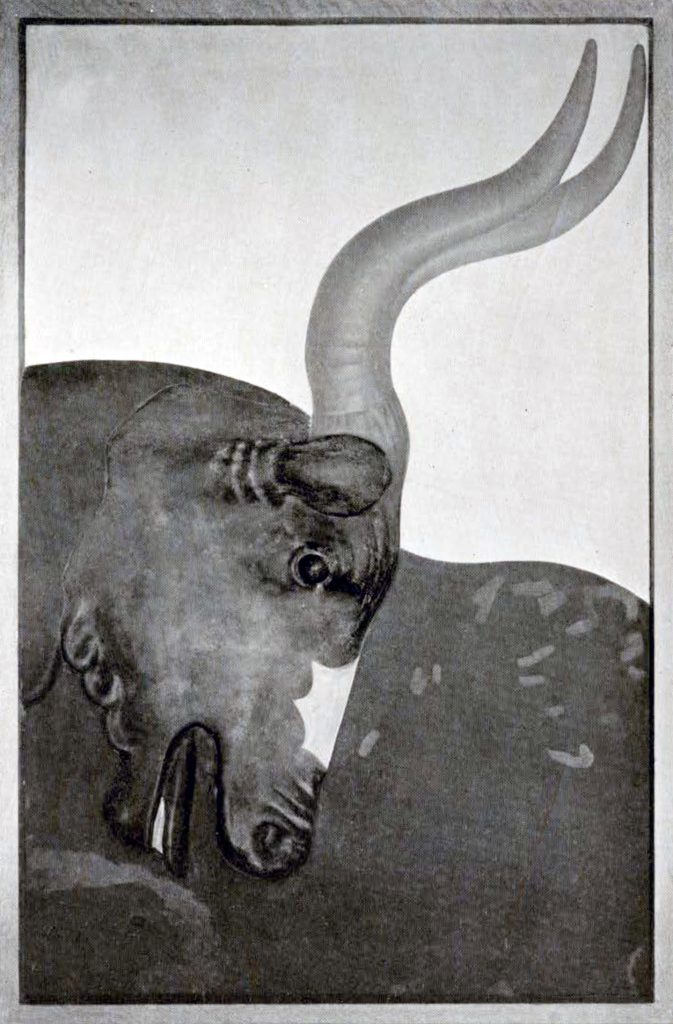

The frescos found in the neighborhood of the north entrance of the palace show scenes entirely different. The largest, a painted relief, contained originally two bulls, one a pale yellow color with red spots, the other a reddish color with spots of bluish white. A part of this second bull is preserved and is shown in Fig. 86, one of the most spirited pieces of modeling which has come down to us from this remote era.

Near this north entrance was found a heap of small bits of painted plaster which had apparently been thrown out in comparatively recent times by modern vandals who used the site of the Knossos palace as a quarry for building-stones. With infinite patience M. Gillièron has pieced these bits together and has restored a whole series of “miniature frescos.” These frescos show better than any other one find from the palace the astonishingly modern character of Minoan life. Men and women are mingling freely with one another; in the case of this fresco they are collected “before the façade of a small but brilliantly decorated shrine of combined woodwork and plaster construction. A special characteristic of these designs is the outline drawing in fine dark lines. This outline drawing is at the same time combined with a kind of artistic shorthand brought about by the simple process of introducing patches of reddish brown or of white on which groups belonging to one or the other sex are thus delineated. In this way the respective flesh tints of men and women are given with a single sweep of the brush, their limbs and features being subsequently outlined on the background thus obtained. . . . At a glance we recognize court ladies in elaborate toilette. They are fresh from the coiffeur’s hands with hair frisé and curled about the head and shoulders and falling down the back in long, separate tresses. They wear high, puffed sleeves joined across the lower part of the neck by a narrow cross-band, but otherwise the bosom and whole upper part of the body appears to be bare. Their waists are extraordinarily slender and the lower part of their bodies is clad in a flounced robe with indications of embroidered bands. In the best executed pieces these decolleté ladies are seated in groups with their legs half bent under them, engaged in animated conversation emphasized by expressive gesticulation.”

A fresco portraying the head of a girl (Fig. 85) found in this part of the palace is carelessly drawn, but is interesting as showing another type of Minoan dress. The bodice seems in this case to be looped up behind in a knot and across the bosom is an openwork pattern of red and blue beneath which is shown the white color of the flesh.

The eastern wing of the palace was largely given over to private suites. The ” queen’s megaron ” in one of these was lit in the prevalent Minoan fashion by light-wells, one of which was decorated with a delightful picture of marine life. The tones are cool, mostly blues and yellows, and the creatures of the sea, dolphins and smaller fish together with the rocky bed over which they dart and play, are rendered with a freedom that recalls the best work of Japanese artists. Only one painting can compare with it, the flying-fish fresco, which was found in a small house of the prehistoric village discovered by English archaeologists at Phylakopi, Melos. The method of the two pictures is the same and it is probable that the Phylakopi picture was either executed by a Cretan artist or was painted by a local artist from designs sent over from Crete.

A fresco which shows the cruel side of Minoan life was found in bits in the northeastern part of the palace at a spot where it had fallen from the crumbling walls of an upper room. It portrays the horrid sport in which the lords and ladies of the palace apparently took delight, and gives a hint as to what befell the annual tribute of youths and maidens sent over to Crete from the mainland. Three toreadors are shown, a boy and two girls. “In the center of the picture the great bull is seen at full charge. The boy toreador has succeeded in catching the monster’s horns and turning a clear somersault over his back, while one of the girls holds out her hands to catch his as he comes to ground. But the other girl is just at the critical moment of the cruel sport. The great horns are almost passing under her arms, and it almost looks an even chance whether she will be able to catch them and vault, as her companion has done, on the bull’s back or whether she will fall and be gored to death.”

Museum Object Number: MS5303

The citadel of Tiryns must now be ranked second to the Knossos palace as a source of prehistoric paintings. A few bits of painted plaster were found by Heinrich Schliemann as early as 1884, but it is in recent years in the course of supplementary excavations undertaken by the German school at Athens that the greater number was recovered. Many of them were found beneath the levels of the floors cleared by Schliemann; others were found in waste-heaps where they had been thrown out in antiquity at a time when the palace was being renovated.

A few of these, those found below the levels of later floors, are from the earlier palace, the date of which is approximately 1600-1500 B. C. Three of these are shown in the exhibition. The pattern of one of these, representing rosettes and stalks, is entirely new; that of another is familiar both from painted vases and from the sculptured roof of a tomb of Orchomenos. The pattern of the third consists of a row of Mycenaean shields covered with skins of various colors. The lines down the middle of these shields were apparently intended to represent the dorsal lines of the hides. In coloring this is one of the richest frescos; it is the only one in which green is used.

Of the frescos from the later palace at Tiryns, one of the most interesting is that which represents a procession of women. It was a large mural decoration of which now only a small part is left. No less than 1600 fragments from this fresco were found, but this was not enough to complete any one figure. The restoration is a composite picture made up of fragments of various figures. As to the correctness of the contours there can be no doubt, but it is of course possible that portions of costume have been joined together that originally belonged to separate figures. The costume is similar to those represented elsewhere in Minoan art, but the coiffure is quite new. The German scholars estimate that at least three frescos portraying processions of women adorned the walls of the Tiryns palace. This one seems to have been painted to replace an earlier picture of the same subject. The explanation offered to account for the popularity of this theme is that these processions were a part of religious ceremonials in honor of a goddess whose cult was in charge of women. It is interesting to note that the ivory casket carried by the woman is the counterpart of one found many years ago in a beehive tomb at Menithi in Attica.

Museum Object Numbers: MS3982 / MS3981

Early Ægean Stone Vases

Like the early inhabitants of Egypt, the people who lived in Crete in the bronze age were skilful workers in stone. Already in the latter part of the third millennium B. C., Minoan artists could fashion from the most refractory stones, vases which for delicacy of form and perfection of finish rivaled the products of contemporary artists in Egypt. The highly colored stones in which the soil of Crete abounds, breccias, veined marbles, alabaster, and variously colored soapstones were skilfully used by these artists, often in such a way that the veinings of the stone appear as borders and bands on the vases. The Museum possesses an interesting set of stone vases dating from 2500-1300 B. C. But the rarer examples of stone-cutting remain of course in Crete and in Greece, and of these the Museum has recently purchased a set of reproductions, made by M. Gillièron of Athens.

First may be mentioned a group of lamps, two of which were found at Mycenae, the rest at various Cretan sites. The taller specimens were probably stationary, for similar lamps have been found on the landings of staircases and at the entrance ways to rooms. The smaller lamps were doubtless carried from room to room. All have a central depression for oil and two grooves for overhanging wicks.

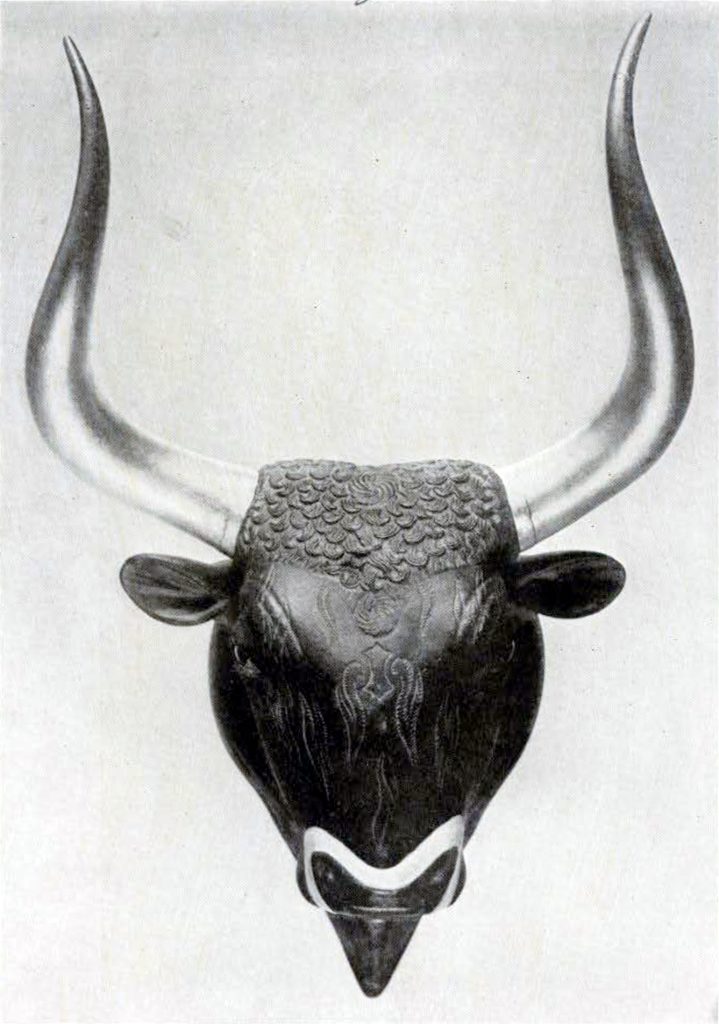

In the ” Little Palace,” a dependence of the great palace of Knossos which was connected with the main building by a causeway, was found a remarkable rhyton of black steatite in the form of a bull’s head (Fig. 88). Only half of the vase was found; the rest was restored. ” The modeling of the head and curly hair,” writes Sir Arthur Evans, the discoverer of this splendid specimen, ” is beautifully executed and some of the technical details are unique. The nostrils are inlaid with a kind of shell like that out of which cameos are made, and the one eye which was perfectly preserved presented a still more remarkable feature. The eye within the socket was cut out of a piece of rock crystal, the pupil and iris being indicated by means of colors applied to the lower face of the crystal which had been hollowed out and which had a certain magnifying power.” This rhyton from Knossos is in general style closely analogous to the gold rhytons from Mycenae and the dark surface of the carefully wrought stone brightened here and there by the colored inlays compares very favorably with that of the more costly gold.

Museum Object Numbers:

MS5341 / MS5338 / MS5342 / MS5322 / MS5323 / MS5339 / MS5324 / MS5325 / MS5337 / MS5340 / MS5335 / MS5333 / MS5319 / MS5318 / MS5317 / MS5336 / MS5334

Image Number: 2483

The three most famous vases of black soapstone were found by the Italian mission at the Minoan villa at Ayia Triatha. They are richly ornamented with sculptured scenes so delicately and vigorously rendered as to constitute in themselves sufficient proof of the high skill attained by sculptors in this remote era. Sir Arthur Evans had already announced his belief that such vases of carved steatite were originally covered with a thin coating of gold-leaf to give the effect of vases of gold with repoussé ornament, when the English excavators at Palaiokastro found a fragment of such a steatite vase to which a bit of gold leaf was still adhering. We must imagine then that the vases from Ayia Triatha had once the same appearance as the Vapheio cups and that the gold-leaf had either been stripped away by plunderers or had simply peeled off in the course of time.

Image Number: 2482

The largest of these three vases (Fig. 89) stands eighteen inches high and is of the same conical shape as that carried by the cup-bearer in the fresco from Knossos (see page 157, Fig. 84). It is divided horizontally into four zones, in three of which are depicted boxers in every possible attitude of the ring, whereas in the fourth is shown a scene of the arena with the inevitable bull-grappling, a tragic scene too in which the victim has missed his grasp. The modeling of these figures is admirable; the waist is conventionally small, but there is the action and élan characteristic of the best Mycenaean work.

Of the second vase which portrays another scene of lively and vigorous action the lower part was not recovered, so that the figures from the knees down are restored. The shape of the vase could be accurately determined on the analogy of a clay vase from eastern Crete. The procession of men which forms the subject of the decoration has been variously interpreted; some have thought it a band of victorious soldiers, others a company of harvesters, but the latest and most credible theory is that it is a sacrificial procession and that the three-pronged instruments which the men carry are the spits on which the entrails of the victims were roasted. This theory harmonizes well with the fact that a band of singers is found in the procession, headed by a man with a sistrum, and that the entire procession is led by a man in elaborate ceremonial dress. However this scene be interpreted, the chief interest in the relief is to be found in the high artistic skill with which a moving body of men is shown. They are broken into groups by men looking backward over their shoulders and by those who have stumbled and are in danger of being trampled upon by the onrushing throng. And the whole company is stepping high and the singers singing lustily with characteristic Mycenaean vigor, a wonderful piece of work for 1600 B. C.

The last of the three vases is perhaps the most charming of them all, and the most modern in its feeling. It is only about five inches high. Five figures are included in the scene which decorates this vase. Three of these are soldiers who stand behind their “man-encircling” shields of bull’s hide. Of the other two, one appears to be a captain. He wears his hair long and flowing and his arms and throat are decorated with bracelets and a golden collar. In his hand he carries a long staff which appears to be a badge of office. The youthful figure who confronts him and who is apparently receiving orders has something of the grace and earnestness of the younger boys on the Parthenon frieze or of the children of Donatello. Both the captain and the boy wear a kind of puttees somewhat different from the ordinary footgear.

E. H. H

Museum Object Number: MS5357

Image Number: 2467

Museum Object Number: MS5364

Image Number: 2471

Image Number: 2477

Image Number: 2501

Museum Object Number: MS5356

Image Number: 2487