In the fourth book of the Iliad after Pandaros has succeeded in sending an arrow through the fastening of Menelaos’s breastplate, the poet interrupts his story to liken the blood-stained body of the hero to an ivory cheekpiece of a horse dyed with purple.

“As when some woman, Maionian or Karian, staineth ivory with crimson dye, that it may be a cheekpiece for some steed; stored in a chamber it lieth and many a knight is fain to wear it, but for some king it bideth there alike to adorn his steed and to be the pride of his charioteer, in such wise, I weep, Menelaos, were thy goodly thighs, thy knees, and fair ankles and fair breast stained with gore.”

Museum Object Number: MS1757

Image Number: 3616

The passage shows that as early as the Homeric period the cheekpieces or guards of a horse’s bit were elaborately wrought of costly materials. In the classical period, likewise, great care was expended upon these parts of a horse’s bridle. They appear often. clearly delineated, in Greek vase paintings of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C., they are conspicuous in sculptured monuments of the Roman period, and the actual bits with their accompanying cheekpieces are of frequent occurrence in the tombs of Etruria. In general it may be said that ancient guards for bits are both larger and more elaborate in form than those in use at the present time. In 1865 an Italian scholar, Stephani, made a special study of ancient horse bits and collected the various types of cheekpieces which adorn them. They may be rectangular, circular, semicircular, or triangular in shape; or occasionally they are in the form of the letter S, or of a horse or other animal. Frequently they are provided with pendants to rattle and jingle with the motions of the horse’s head.

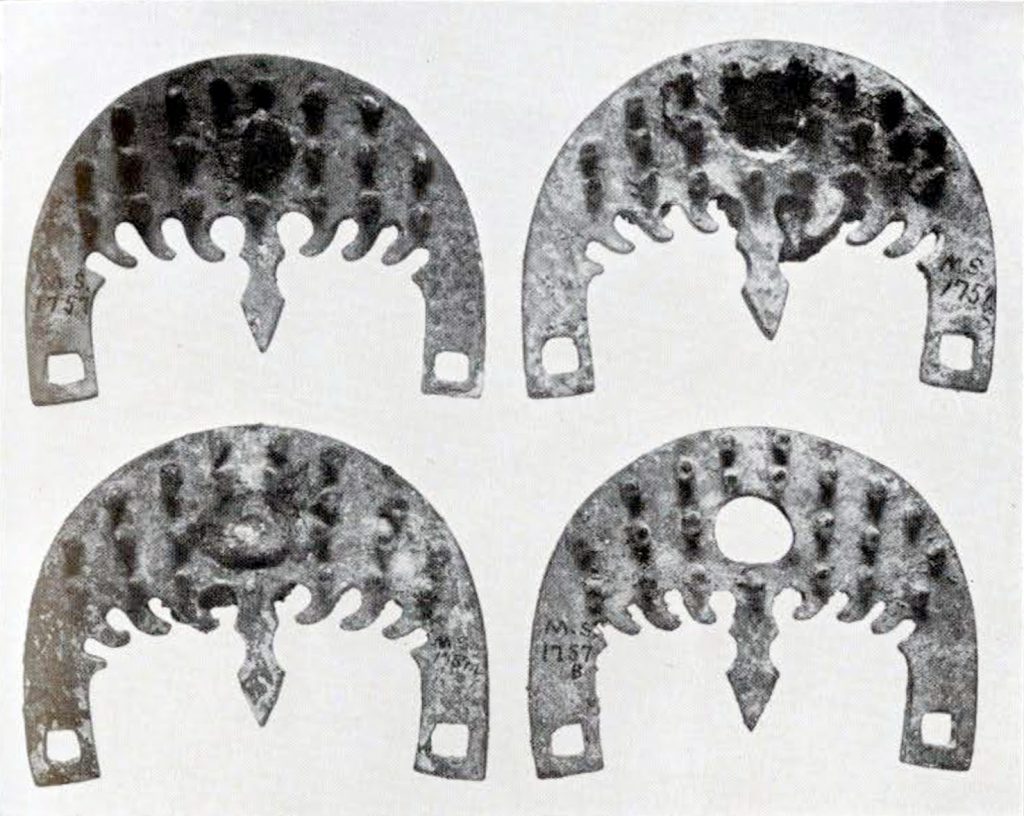

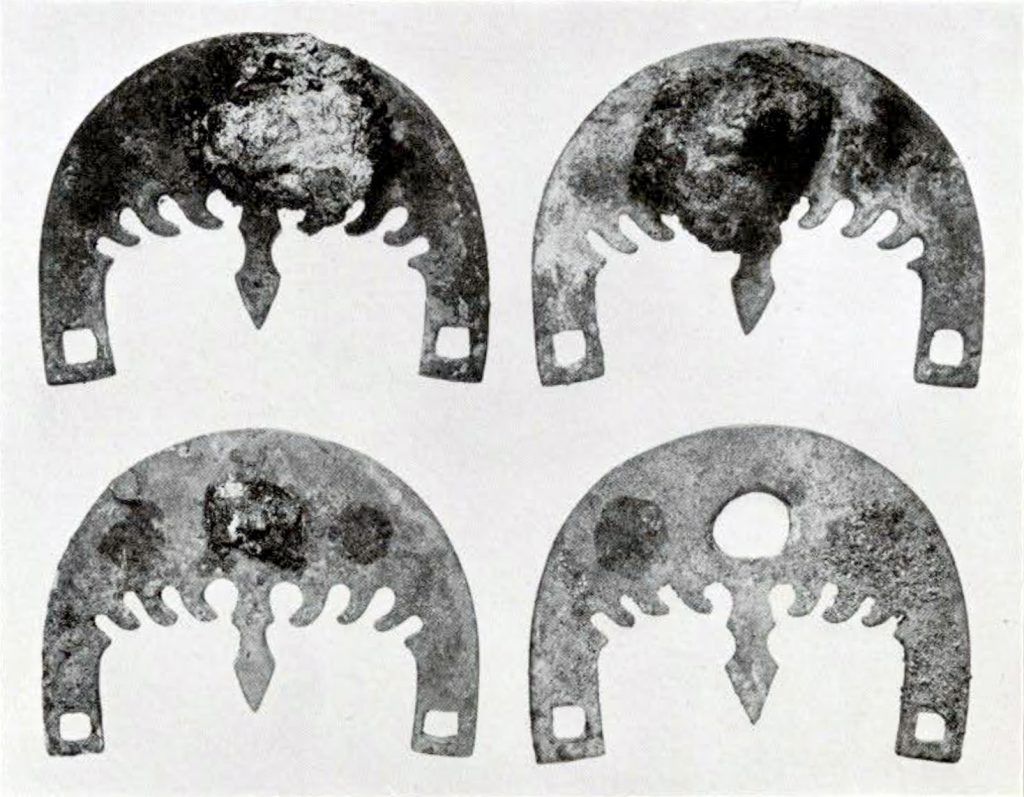

The Museum has had in its possession since 1897 four bronze objects which have long passed as horseshoes. In fact, they have been reported as the only ancient horseshoes in existence. They were published as such in 1892 in the American Journal of Archaeology. These objects measure four and three-quarter inches across and, as may be seen by the illustrations, are shaped something like horseshoes. One side of each is provided with a number of small spikes (Fig. 102). Each has three perforations: a single central hole, oval in outline, with a mean diameter of three-fourths of an inch, and a pair of holes at the extremities, three-eighths of an inch square. In three cases the central holes are still choked with masses of corroded iron. According to the theory which claims that these objects are horseshoes, they were attached by a single iron spike through the central hole and two leather thongs passing through the square holes.

Museum Object Number: MS1757

Image Number: 3617

A cursory examination of the objects reveals facts which do not harmonize with the theory that they are horseshoes. In the first place, the idea that a shoe was fastened to a horse’s hoof by means of an iron spike three-quarters of an inch in diameter cannot be accepted without question. In the second place, the objects show no signs of wear, and the bronze spikes which, according to the theory, were on the bottom of the shoe, show no signs that they have ever sustained the weight of a horse.

Museum Object Numbers: MS1757, MS1758

Image Number: 3614

Museum Object Number: MS1754

Image Number: 3102

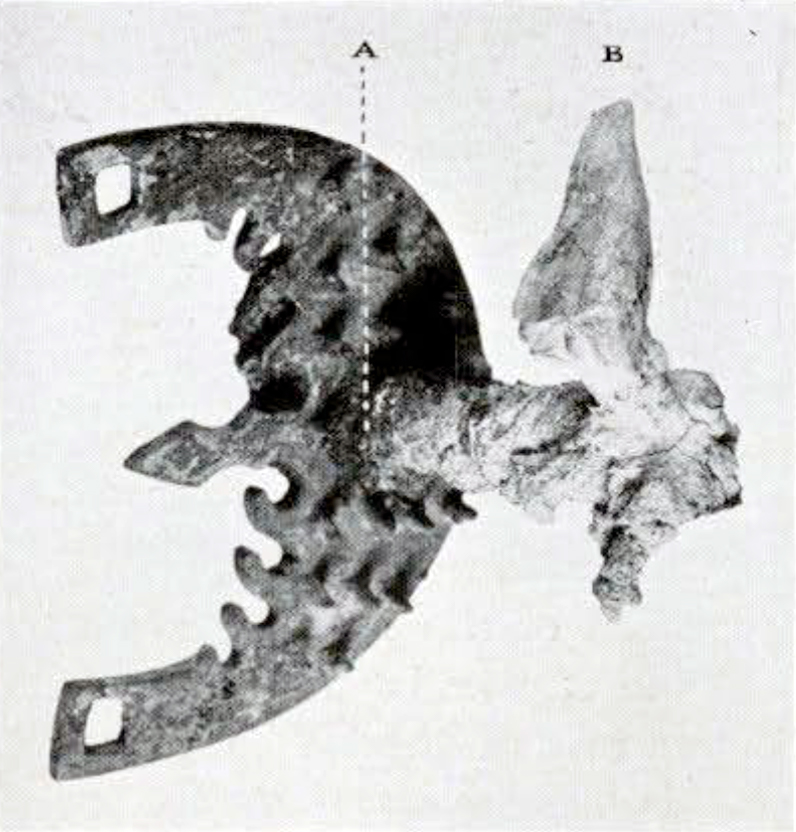

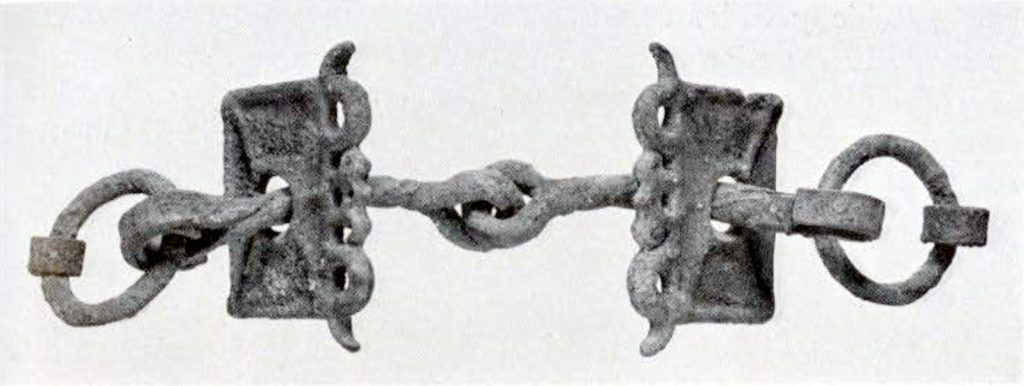

The objects in question were found in a tomb at Corneto in Etruria, and fortunately a number of odds and ends from this tomb were preserved by the excavators and were acquired by the Museum along with the bronzes. Among these miscellaneous objects were horse’s teeth, some of them stained green from juxtaposition to bronze, and a quantity of fragments of corroded iron. The largest piece of iron, measuring between three and four inches in length, is slightly curved at one end and in the mass of corroded iron which adheres to the bar at this point is lodged a horse’s molar tooth (Fig. 104 B). The other end of this bar exactly fits the piece of broken iron which remains in the central hole of one of the pieces of bronze. The joint is shown at the point marked A in Fig. 104. This iron bar together with the telltale tooth reveals the purpose of the bronze plates. They were the cheekpieces of iron bits. This view is confirmed by an examination of the lumps of iron on the outside of the cheekpieces. Corroded and misshapen as they are, the outlines of the perforated ends of the bits and of the rings which passed through them are clearly discernible (Fig. 103). For purposes of comparison another ancient bit in the possession of the Museum is shown in Fig. 107. The outer ring held the rein and possibly also the strap which attached the bit to the rest of the bridle, although it is more likely that straps for the purpose were held by the smaller square holes. The piece of iron to which the horse’s tooth adheres in half of a bit and the curve in the end of it is the remnant of the ring by which it was attached to the other half. The spikes on the inner surface of these cheekpieces are analogous to the burrs which are still used on bits in cases where the horse does not guide easily. Similar spikes appear also on a bit of the eighteenth or nineteenth dynasty from Thebes.

Museum Object Number: MS1754

Image Number: 3101

The fact that bronze and iron are used together in the construction of these bits need cause no surprise. Every collection of Etruscan antiquities contains objects in which these metals are combined. More over, an iron bit with bronze cheekpieces was found some years ago in Vetulonia. Nor need it be a matter for surprise that two bits were found in the same tomb, for they have frequently occurred in pairs in Italian tombs. The presence of bits and still more the presence of the teeth and bones of horses in these tombs has been generally held to imply that horses were killed at the burial of their masters that they might accompany them to the next world.

The other objects recovered from this tomb are a few bits of iron which apparently formed the rim of a wooden box, oval in shape, and a single clay vase painted in the manner which was in vogue among the potters of southern Italy in the fourth century B.C. In addition to fixing the dates of the hits this vase is of itself of considerable interest. It is a lineal descendant of the Attic kylix, but both the handles and the stem which in Attic vases connects the bowl with the foot are here missing. The decorative patterns, an ivy wreath on the outside and a wave pattern about the center on the inside, are both characteristic of the art of southern Italy. The gorgon’s head in the center, although it will not bear comparison with the gorgons of the best black-figured vases, is nevertheless an imposing piece of decorative art.

E. H. H.

Museum Object Number: MS1637

Image Number: 3613