An Ionic Amphora

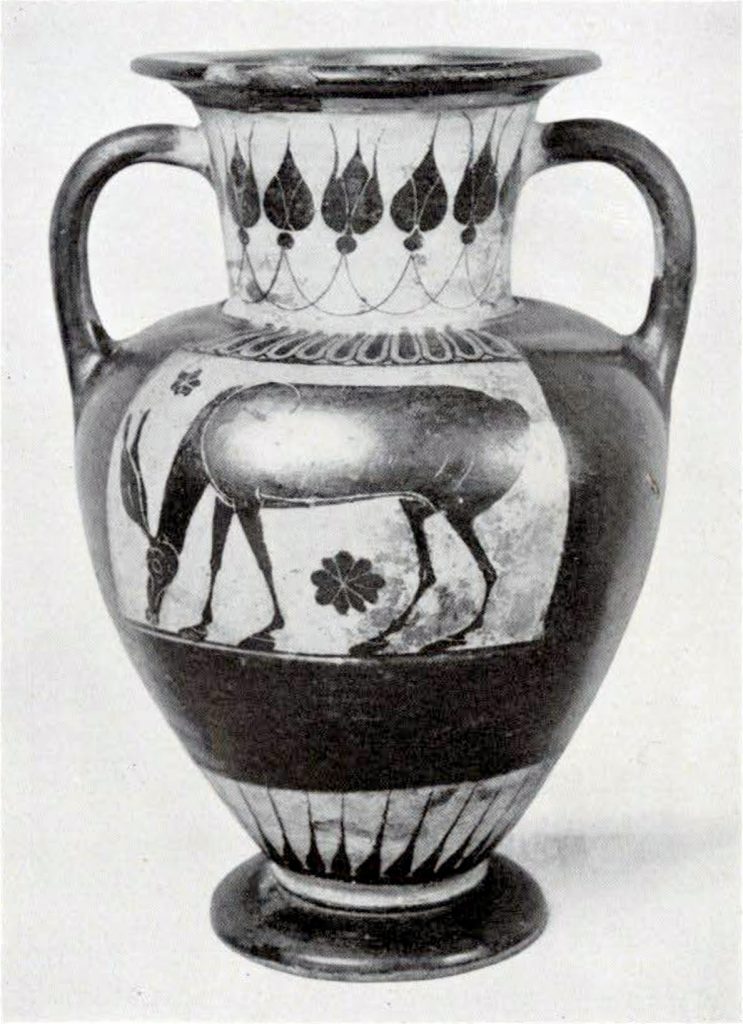

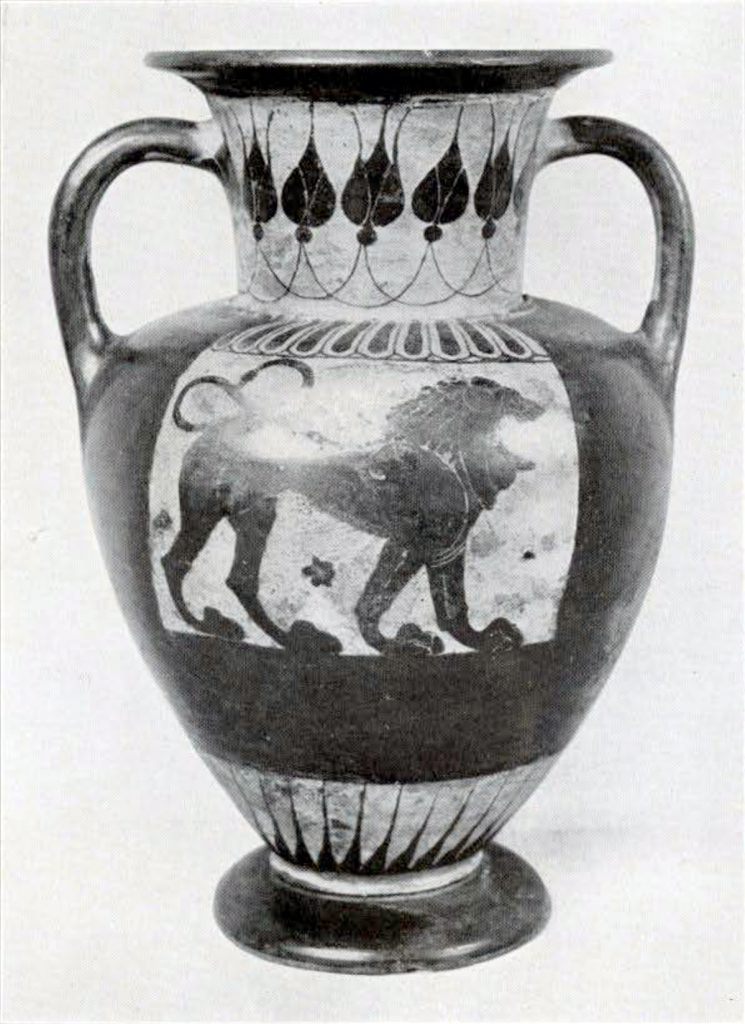

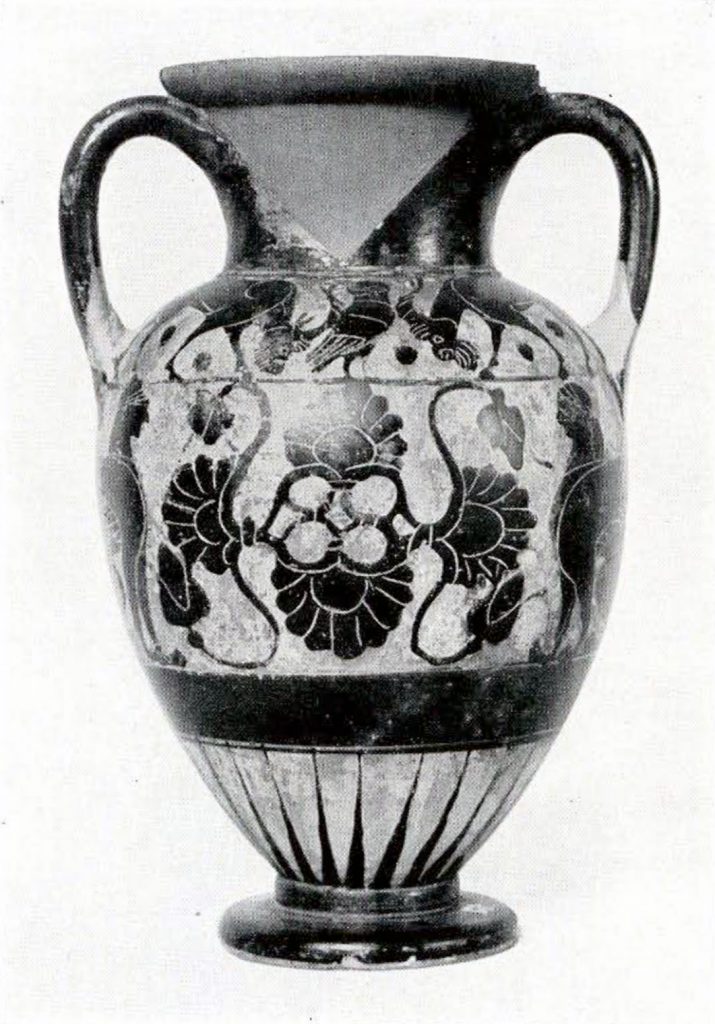

In 1896 the Museum purchased a group of eight vases which had once belonged to Tewfik Pasha, Khedive of Egypt, and which, according to report, had been bought in the Greek islands, “chiefly Chios and Samos.” One at least of these vases was made in a region remote from the Greek islands, in southern Italy, several were made in Attica, but one, a black-figured amphora, is a typical product of the Ionic soil in which it was reported to be found. It is a small shapely vase the very form of which bespeaks Ionic taste. Ionic too is the delicate lotus pattern on the neck and the graceful, lively rendering of the two animals, a roaring lion and a grazing deer, which decorate the two reserved panels.

Image Number: 4646

The vase measures 95⁄8 inches in height and 6¼ inches in widest diameter. The lip is flat, the neck moderately high with only a slight contraction toward the shoulder from which it is marked off by a ridge. The beautiful outline of the shoulder approaches that of a stamnos. The foot is slightly rounded and, like the neck, is separated from the body of the vase by ridge. The handles are round. The greater part of the outer surface of the vase as well as the inside of the neck is covered by a black glaze; the unglazed parts which serve as background for the designs in black are the neck, decorated with the lotus chain, the two panels, decorated on the shoulder with a tongue pattern and on the body of the vase with the lion and deer respectively, and the part of the vase just above the foot, decorated with a ray pattern. The surface of the clay where it has not been protected by the glaze is so worn that the dark designs appear to stand out in relief. Only in one or two places is the original surface of the vase preserved to the height of the glazed portions, but these are enough to show both that this effect of relief is entirely accidental and that the original color of the clay surface was a warmer red than at present. The details of the design are rendered by incised lines which were once filled with purplish paint. Only the faintest traces of this coloring now remain. The original sketch for the design was also rendered by incised lines which in several places diverge from the finished picture, betraying thus a change in the artist’s design.

Precisely the same technical peculiarities which characterize this vase are to be found on an amphora in Munich recently published in the first volume of the new catalog of the Pinakothek.

Museum Object Number: MS401

Image Number: 3444

This vase is slightly larger than the one in the University Museum, but the shape is the same. There is the same fiat lip, round handles, and boldly curving shoulder. Even the ridges which mark off the neck and foot are to be noted in both. The original surface of the unglazed parts is worn away on both and both show conspicuous wheel marks immediately at the sides of the panels. Similar too is the use of incised lines and of purple paint. In design, also, the two vases closely correspond; the paws of the lion on the obverse seen in Fig. 110 are similar to those of the sphinxes on the other which is shown in Fig. 108, and the lion’s tail in the shape of a figure eight is like those of the sphinxes. There is also the same use of rosettes as stop-gap ornaments. Altogether there can be no doubt that the two vases are products of the same workshop.

Now the amphora in Munich has been assigned to a group of vases which are thought to be all of the same fabric and which take their name from the most famous vase of the group, the Phineus kylix at Wurzburg. Thus the Munich amphora is entered in the catalog of the Pinakothek as “Amphora from the workshop of the Phineus kylix.” The correctness of this identification is confirmed by the resemblance of the vase under discussion to the Wurzburg kylix. If, for example, the lion which helps to draw the chariot of Dionysos on the latter be compared with that on the former, it will be seen that the eye, the under jaw, the mane, and the paws are all .rendered in the same manner on the two vases. The combinations of short lines on the heads of the deer on the two vases are also very much alike. The unusual kind of clay with its tendency to wear away and leave the glazed parts in relief is also characteristic of the Würzburg kylix. And lastly, the freshness and vigor of the paintings of this more famous vase are found also, if to a less degree, on the panels of the other. This Ionic vase of the University Museum may accordingly be assigned to the workshop of the Phineus kylix, which was operated on Ionic soil, perhaps at Naxos, in the middle of the sixth century B.C.

Two Italian-Ionian Amphorae

The Ionian artists of the sixth century B.C. not only attained preeminence in Greece, but also enjoyed for a time the hegemony of the artistic world of central Italy. Ionian artists were employed to decorate the walls of Etruscan tombs and Ionian foundries and potteries produced vases of metal and of clay which exerted a dominating influence over the crafts of the Etruscans. But this colony of Greek artists did not remain permanently in Italy, and at the end of a hundred years the production of vases seems to have passed again into the hands of native artists.

Museum Object Number: MS401

Image Number: 3443

The record of this sojourn of Ionian artists in the west may be traced from painted vases. The tombs of Caere and of Vulci have yielded vases painted in a manner which is clearly Ionian but which differs from that of other Ionian vases. These vases are found only in Etruria, and hence the conclusion that Ionian artists established potteries there in which they produced their own particular fabric. A representative vase of these Ionian potters established on Italian soil has been published in the first volume of Furtwaengler and Reichhold’s Griechische Vasenmalerei. In graves of a later date than those in which the pottery of Ionian potters is found, occur vases which still show many of the earmarks of Ionian art but which are executed in a clumsy manner; in a still later context are found vases of a barbarous and crude style that betrays far less Ionian influence.

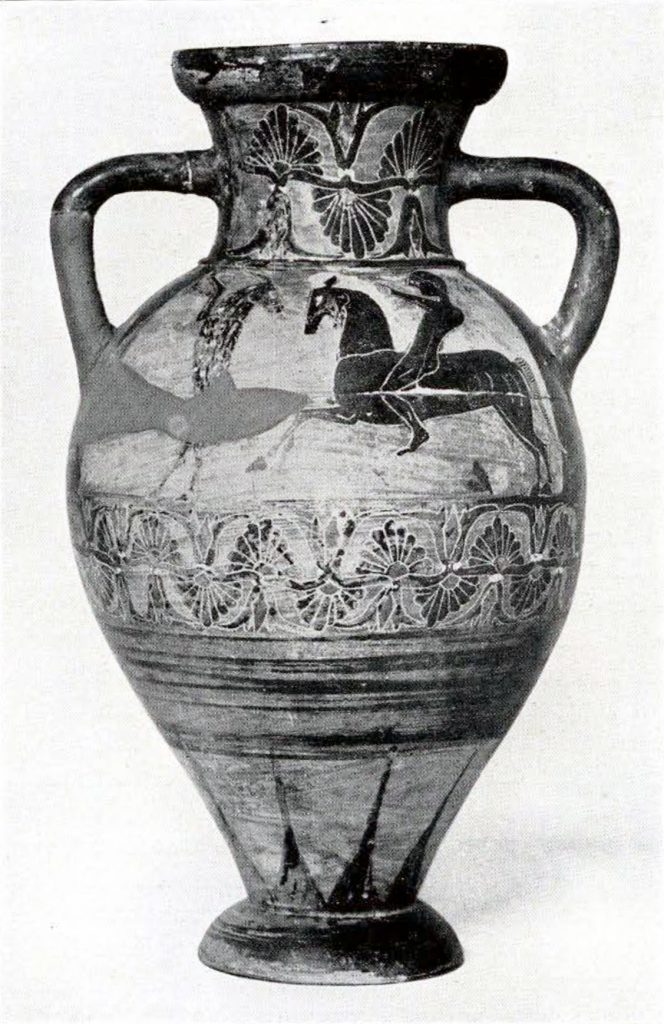

Museum Object Number: MS2490

Image Number: 4688

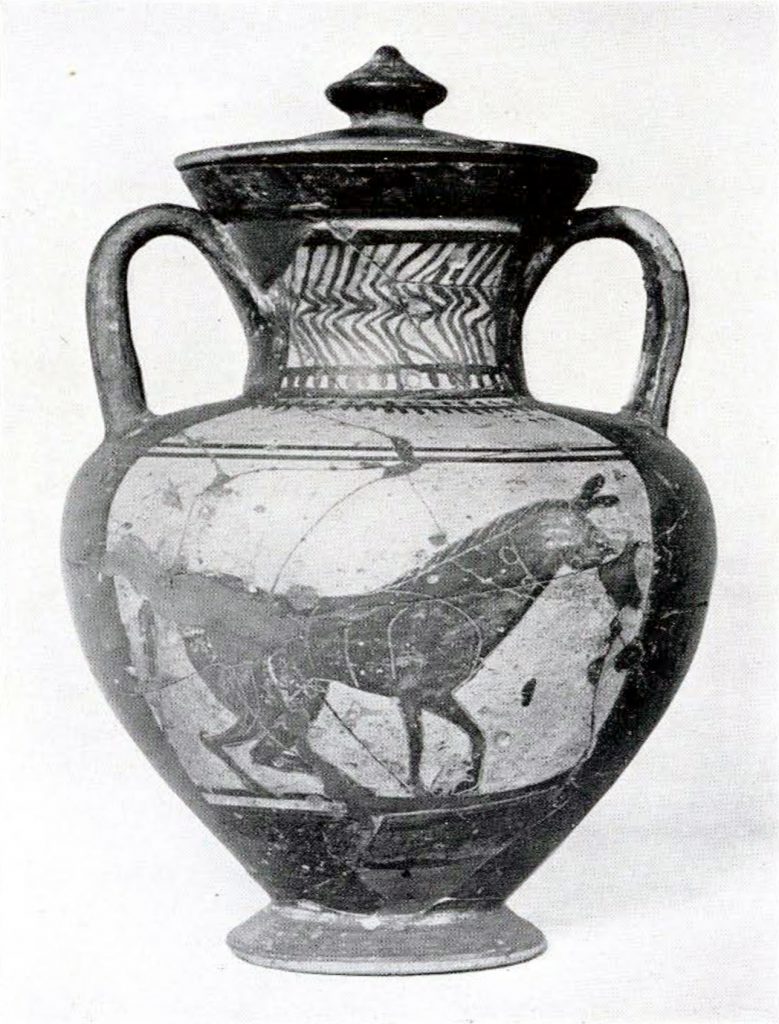

Two amphorae from Orvieto which have been in the possession of the Museum since 1897 represent these two later phases of Italian-Ionian art. The earlier of the two is an egg-shaped amphora with cylindrical neck and round, spreading handles. The vase is not evenly fired; on one face the clay is a warm buff color and the painted parts reddish, on the other the clay has a greenish tinge and the lustrous paint is a purplish brown. The entire scheme of decoration is outlined with incised lines. The first sketch for one of the main panels was apparently abandoned, for between the rider and the rearing deer may be seen a shield with an exterior device faintly scratched in the clay.

Nothing about the decoration of this vase indicates a skilled artist. Even the conventional pattern of lotus blossoms and palmettes was more than he could manage. The palmettes are one-sided, the pattern is not spaced properly and does not come out evenly. The main decoration on either face consists of a horseman riding full tilt into a rearing deer. The only explanation for such a senseless design is that the potter picked from the repertoire of subjects used for Ionian vases such figures as pleased him or such, it may be, as he thought were within his powers and then combined them without regard to their appropriateness. This amphora is typical of the output of Italian potters working under Ionian influence.

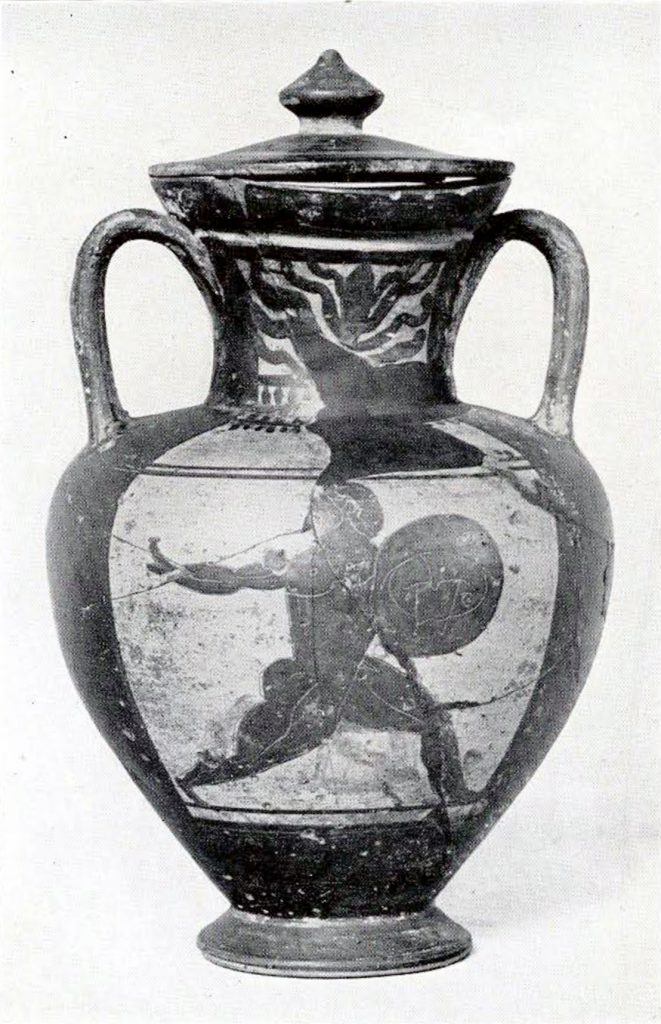

The other amphora makes even a worse showing. It has a high shoulder sharply outlined and triple handles, rudely pared into shape. The lustrous paint which is used both for the undecorated parts and also for the figures of the design is an ocherous red. The two panels on the neck are filled, the one with a crude plant motive, the other with a row of zigzag lines. Within the two main panels on the body of the vase are pictured a horse and a nude youth with extended shield. The outlines and interior details of the figures are rendered with incised lines drawn with a crudeness which is puerile. The ornament on the shield carried by the nude youth may be taken as indicative of the artist’s intelligence. It can hardly be interpreted as anything else than the nose, tongue, and eyes of a gorgon’s head, but the artist appears not to have understood what he was copying and as a result the eyes are on either side of the tongue. The vase shows well the straits to which Italian potters were reduced after they had lost their Ionian masters.

Two Chalcidian Vases

In the middle of the sixth century B.C. the city of Chalcis in Eretria was the seat of a pottery which for a short space of time produced its own local variety of black-figured vases. The provenience of this ware was established some years ago by the identification of the Chalcidian alphabet of the inscriptions written upon these vases. And that the ware was to be traced to the mother city Chalcis rather than to any of her colonies was indicated by the influence of Attic and of Corinthian art observable in the painted designs with which this fabric was decorated. This influence implied a close relationship with Athens and Corinth such as was known to have been enjoyed by the neighboring city of Chalcis. The ware showed, moreover, unmistakable traces of being derived from metal prototypes, and it was known that Chalcis was an important center for the manufacture of bronze vases.

Museum Object Number: MS2490

Image Number: 4687

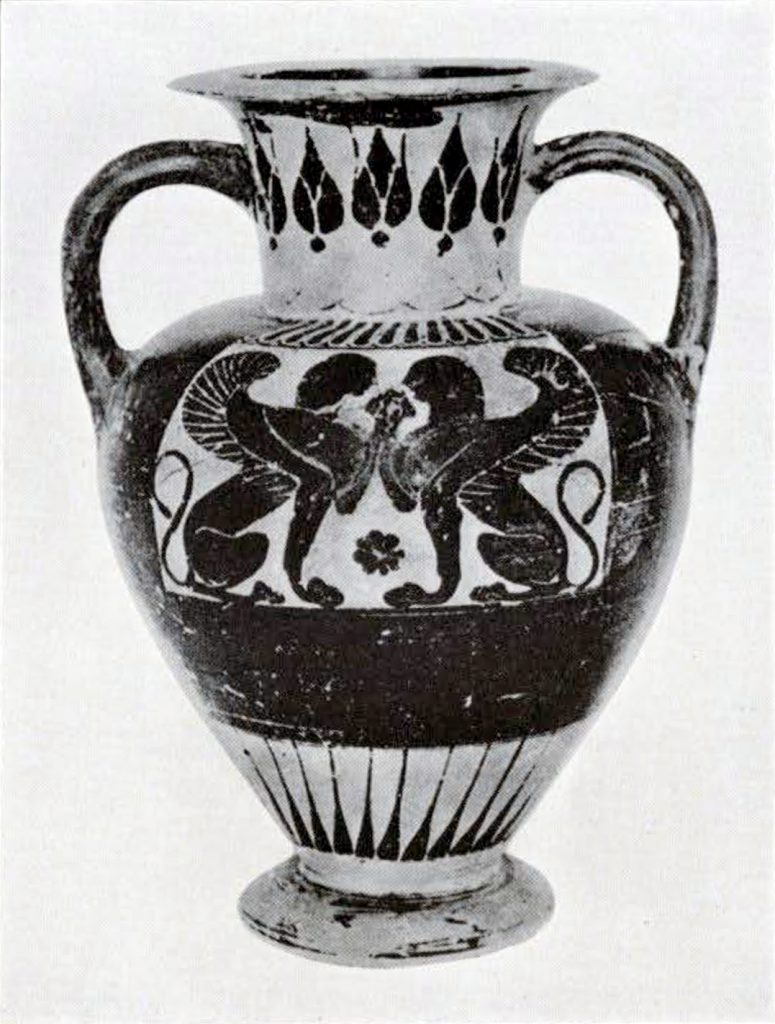

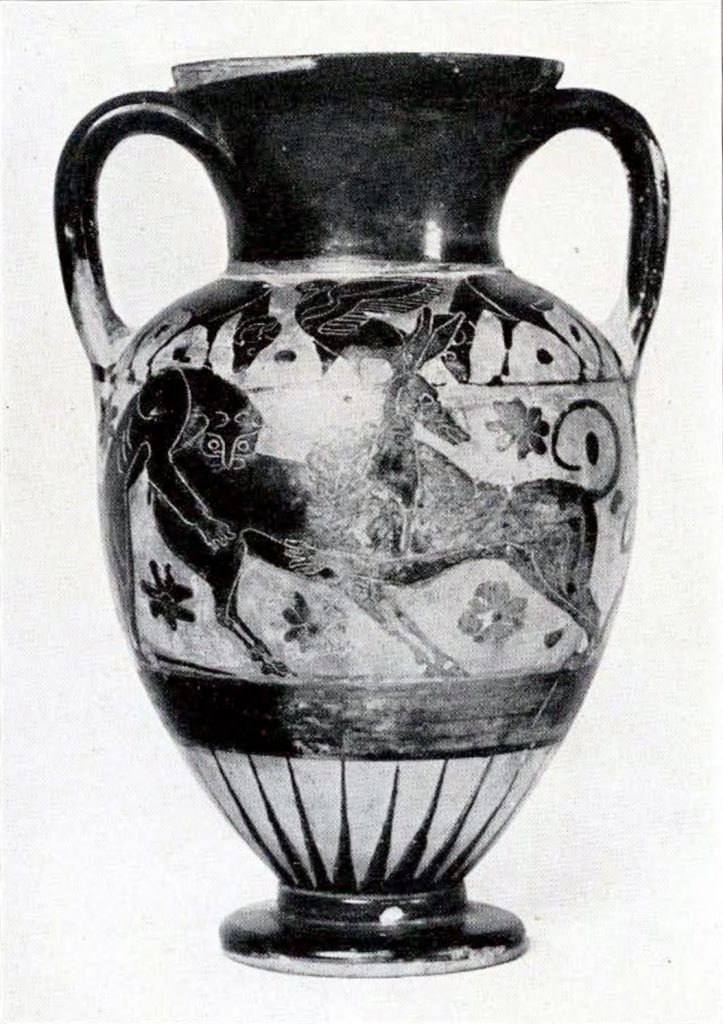

Chalcidian vases may generally be recognized by the symmetrical arrangement of their designs, by the use of small devices, especially the rosette and the lotus bud, to fill the empty spaces of the field, and by a certain carelessness in the rendering of details which nevertheless does not invalidate the spirited drawing of the main contours.

Museum Object Number:MS2491

Image Number: 4689

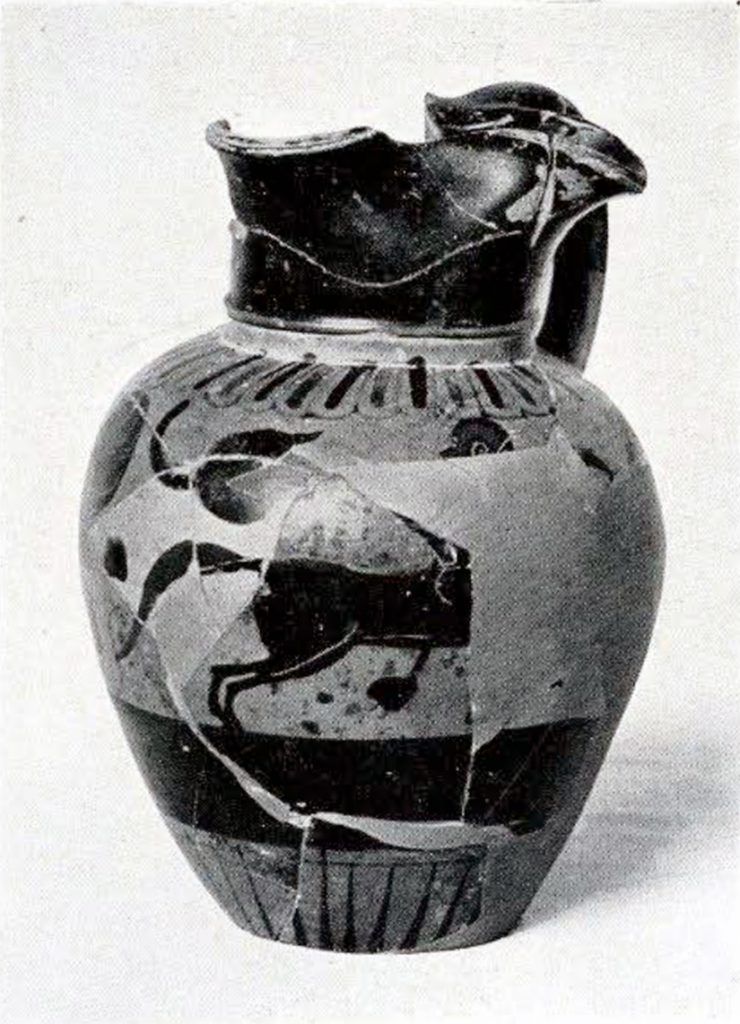

The Museum possesses two vases which display these very characteristics, the one an amphora, the other an oinochoe, or jug with trefoil lip. The amphora, like the Ionic amphora described on p. 218, was once the property of Tewfik Pasha, Khedive of Egypt. It is a slender vase, between eleven and twelve inches in height, of the elegant form preferred by Chalcidian potters. The handles are neither round nor flat but of a type used for metal vases. The foot, the neck, and the greater part of the surface of the handles is black. On the shoulder and around the body of the vase are zones of decoration painted in the true Chalcidian manner. The upper frieze, as Adolf Furtwaengler pointed out in his notes on the antiquities in the museums of America, is the exact replica of the upper frieze of a Chalcidian amphora in the Louvre. On one face are two rams separated by a swan, and on the other two goats and an owl. The empty spaces of the field are filled with dots which are to be taken as a shorthand form of rosettes. A symmetrical arrangement of the ornament appears again in the main zone of decoration on the reverse, where the center of the field is filled with an elaborate device of palmettos and lotus buds, flanked on either side with a sphinx. In the central zone of the obverse are represented two panthers pulling down a deer. The empty spaces of the background are filled with rosettes. The purplish red paint which together with incised lines was used to bring out the details of the figures has almost entirely disappeared. Only faint traces remain, but these are sufficient to show that it was applied profusely to decorate the wings of the birds and sphinxes, to outline the muscles of the animals and to indicate the streams of blood on the flanks of the deer. This amphora has of course no inscriptions to declare its Chalcidian origin, but it may nevertheless be safely ascribed on the ground of style to this small and interesting group of black-figured vases.

The other Chalcidian vase in the Museum was put together two years ago from fragments which were purchased for the museum in Orvieto in 1897. That this specimen was Chalcidian and that the shape was rare among vases of this fabric was suggested to me by Mr. J. D. Beazlcy on his visit to the Museum this autumn. The foot, a large part of the neck, and many pieces from the body of this vase are missing. On the other hand, the surface of the parts which remain is better preserved than on the amphora. Even the white paint used for the faces of the sphinxes has survived on this vase, whereas it has entirely disappeared from the amphora. The main zone of ornament encircles the vase; above it is a band of tongue pattern and below it a broad band of black edged with purple stripes. The design is divided into two parts by a lotus bud beneath the spout. On one side are two sphinxes facing each other; on the other two horsemen or centaurs. So much of the design is missing at this point that it can not be exactly determined. The drawing of the figures of this vase is inferior to that of the animals on the amphora. But it should not be judged too severely; it was doubtless a small informal piece on which the potter did not expend much care.

E. H. H.

Museum Object Number: MS398

Image Number: 4644

Museum Object Number: MS398

Image Number: 4645

Museum Object Number: MS4835

Image Number: 3445