No site in prehistoric Greece is more familiar than the citadel of Tiryns, the gray rock of which rises sheer from the level green of the Argive plain. Though the first excavations on this site were made in 1884, it was in 1909 that the investigation of a waste-heap, thrown out at a late period, led to the discovery of many bits of painted plaster which had once adorned the walls of the palace. Fragments from a dozen large frescoes lay jumbled together in this heap; their painted surfaces were covered with the roots of the plants which for four thousand years had been growing over them. Their colors were faded, much was irretrievably lost, but out of the little that remained it was possible by painstaking study to reconstruct the originals. Reproductions of one of the most important of these reconstructed frescoes were acquired by the Museum in December.

Museum Object Number: MS5454

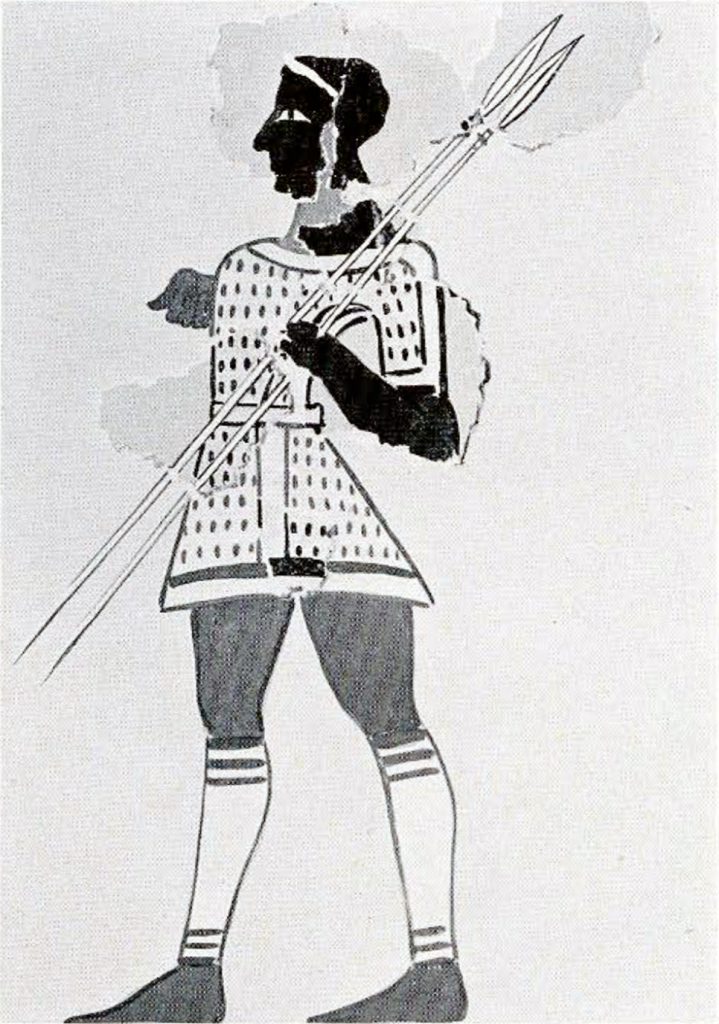

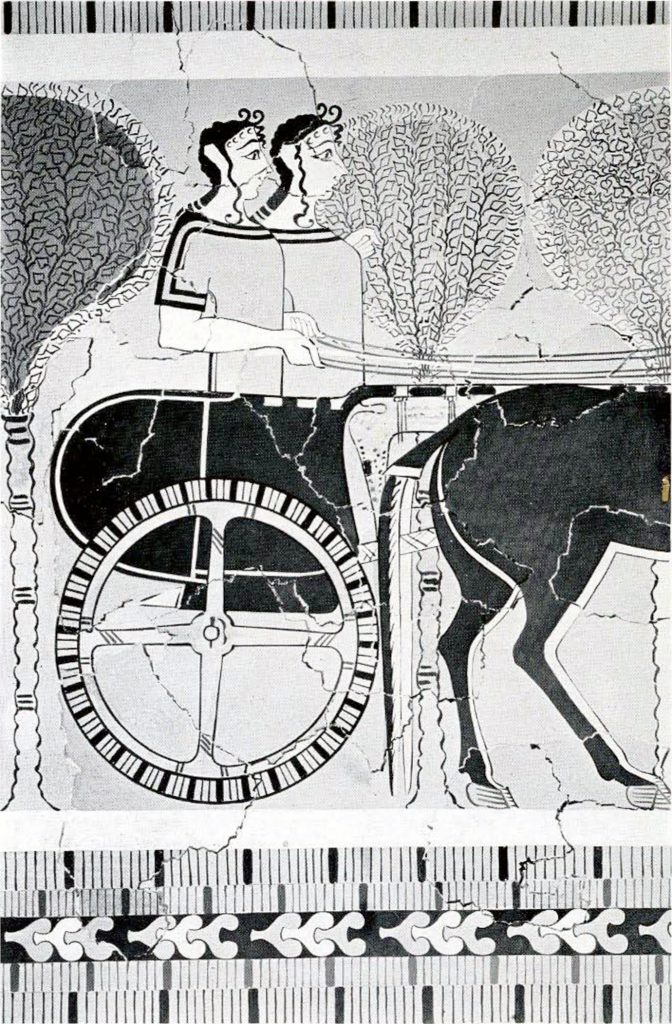

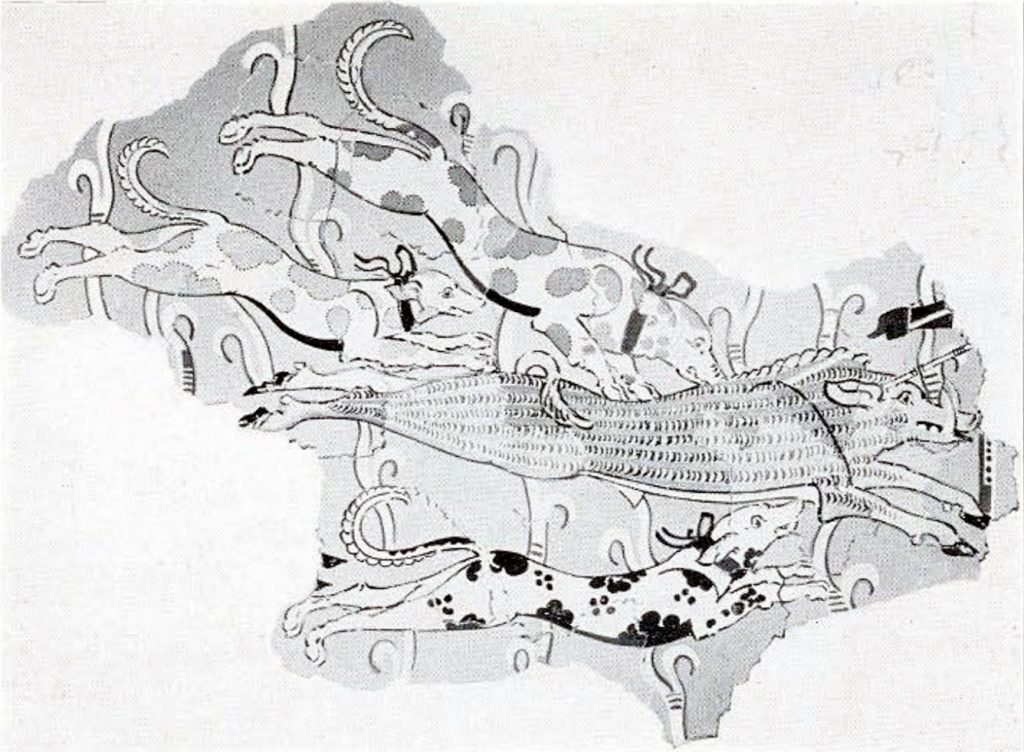

The original fresco appears to have been a long narrow frieze carried around all four walls of an important room of the palace. Even with the architectural patterns which finish it above and below, it measures less than twenty inches in height. The subject depicted is a hunt, the several scenes of which may have been separated from one another by intervening doors or windows. In one section, showing the start, are seen men and women advancing through the forest, some driving in lightly built wagons, each of which is preceded by an attendant with a hound on the leash, others walking and carrying spears. In another scene are represented deer and smaller game which are probably hares, in another boars are caught in nets and in still another are represented exciting kills in which both men and women take part. The length of the frieze can be estimated from the fact that six chariots and six kills were represented. The colors are those usual in early paintings, red, blue, white, black, and the rarer colors, gray and violet.

The importance of this frieze can scarcely be overestimated. For the student of art it shows for the first time how the figures of an extensive mural decoration were arranged, and affords a prototype for the scenes of hunting which are found on Greek vases of the classical period. And for the student of the private life of these earliest inhabitants of Greece, it has a wealth of interest.

Only a very small proportion of the fresco can be restored. Of the parts portraying boars entangled in nets and of those representing deer and hare, only a few small fragments remain. The best preserved fragments are those reproduced here. In Fig. 117 are combined some of the fragments which belong to the scene portraying the start through the forest. The chariot is rendered with great detail, even the pin which passes through the axle and the leather thong which held it in place are clearly shown. The forest is indicated by a row of trees shaped like fans, the colors of which, red, blue, and gray, are entirely conventional. That the chariot was drawn by a pair of horses is indicated by the simple expedient of doubling all the contours of the horse with a line of white. Needless to say the artist does not succeed in showing perspective, nor does he concern himself with the problem of representing the white horse on the further side of the chariot pole. The figures in the chariot or wagon, since their flesh is white, are those of women, with the usual Minoan coiffure and the usual strange position of the thumbs. The dress, however, is entirely unusual for women, for in place of bolero jackets and flounced skirts, they wear plain shifts like those worn by the men. In other words, they have put on men’s dress for the hunt.

Museum Object Number: MS5456

Museum Object Number: MS5457

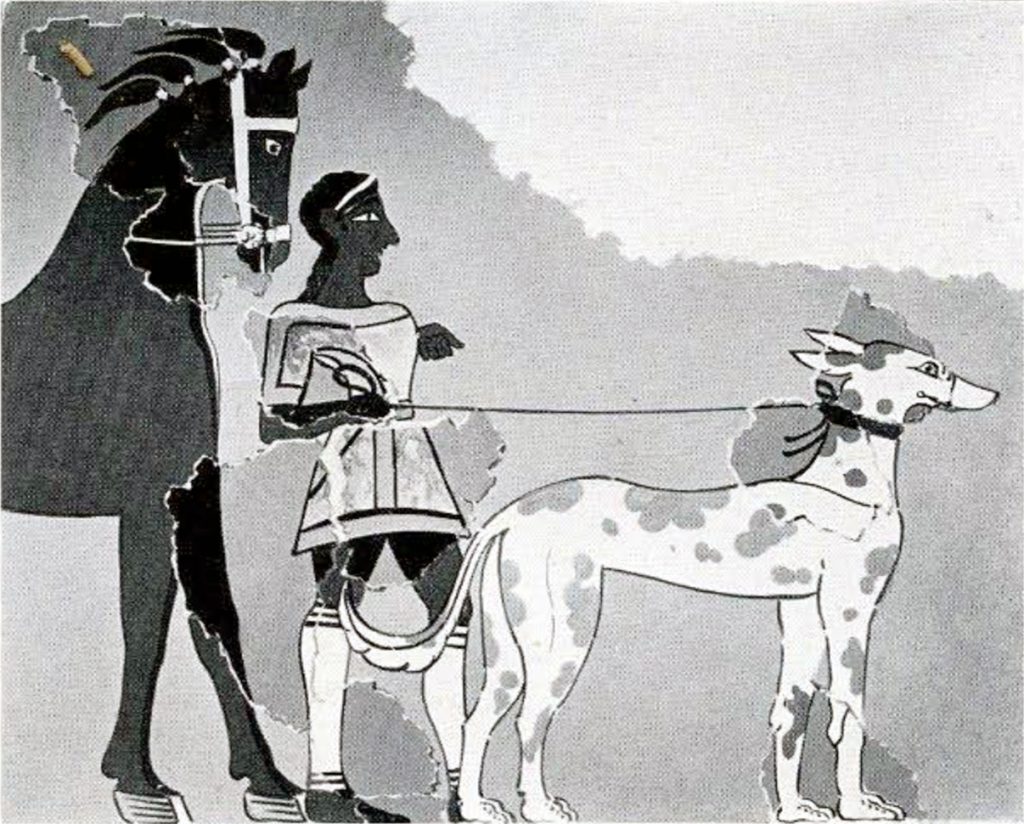

In Fig. 118 is shown a huntsman with a hound on the leash standing in front of a horse. The huntsman wears gaiters fastened above and below by leather thongs. The hound is unmistakably a greyhound, a type which differs widely from that of the hounds shown in Fig. 119. The presence of a greyhound recalls Xenophon’s recommendation of the Cretan greyhound for use in boar hunting, but it has been thought probable that the greyhounds of this fresco are to be connected with the other game depicted in the frieze rather than with the boars. Xenophon has left a description of how the wild boar was hunted in the classical period. He was generally taken in marshy ground. Nets were fastened from tree to tree and the boar was driven towards them by hounds and men. If he turned and charged, men and hounds were to be ready for the attack.

Such a charge is shown in Fig. 119. The marshy ground is indicated by the curving plants. The hounds are represented exactly as on Greek vases, springing at their victim from every side. The huntsman whose hand appears at the corner of this fragment is holding his spear and driving it home in just the manner which Xenophon prescribes. That women shared the dangers of the kill, even as Atalanta did in a later time, is shown by the fact that on one fragment the hand which holds the spear is painted white.

E. H. H.