MENTION has frequently been made in the pages of this JOURNAL of the fragments of Greek vases, which were found in tombs in Orvieto, and were acquired in 1897 by the Museum. It was a fortunate circumstance that these fragments never passed through the dextrous hands of restorers, but reached the Museum in just the condition in which they were taken from the earth. It was less fortunate, however, that the tombs were not carefully enough cleared by the local excavators to insure the preservation of all the smaller fragments. A careful knifing out of corners and crevices and a persistent use of the sieve would doubtless have made it possible to set up these vases in their entirety, with no parts missing; whereas, as a matter of fact, of the twenty-five or more vases which have been restored from these fragments, no one is entirely complete. Yet, in spite of the missing parts, these Attic fragments are to be regarded as one of the most valuable acquisitions to the Mediterranean section of the Museum. Many of the vases restored from them have already been published, but the treasure is still far from being exhausted. In this brief article it is proposed to treat of a series of black-figured covered bowls, which date from the latter part of the sixth century B. C., from the period when Athenian art was flourishing under the enlightened patronage of the Peisistratids.

Museum Object Numbers: MS3439A , MS4846

For two reasons these bowls are worthy of attention. In the first place, the shape is rare; and in the second place, the scene painted on one of them represents a conclave of deities which presents features entirely new.

This shape of bowl is not recorded in the catalogs of either the Berlin or London collections. In the Louvre catalog (F. 149 and 150) M. Pottier has described two “goblets in the form of a chalice,” which are of this type, and in Florence is a similar fragmentary bowl, which bears the signature of Nikosthenes.

This type of vase then is exceedingly rare, so that it is extraordinary that so many examples of this shape should have been recovered from the Orvieto tombs. Four specimens of these bowls, together with their lids, were capable of restoration, and there were also found fragments from several other similar lids, so that the original number of bowls deposited in these tombs was probably greater. The Florence bowl (recently published in Perrot and Chipiez’s Histoire de l’art, Vol. X, p. 261, Fig. 165) is called a Pyxis, but the shape seems too large to have served as a toilet box, and is rather adapted to holding sweetmeats or dried fruits.

The matching of these bowls with their lids is somewhat conjectural, but since no two Greek vases are exactly alike, there are small differences in the width of purple bands, in the thickness of the black varnish, in the spacing of the decorative patterns, that indicate which pieces belonged together.

The most complete of these bowls (Fig. 94) measures, together with the lid, .216 m. in height, and .17 m. in greatest diameter. Its shape is typical. The rim is provided with a narrow ledge for holding the lid, the bowl slopes with a firm and graceful curve toward the stem, a moulded ridge separates the stem from the bowl. The lid is surmounted with a shapely knob. A slight variation from this shape is to be noted in the case of another vase, where a second moulded ridge serves to mark the lower margin of the main field of decoration.

Museum Object Number: MS3438

Image Number: 2785

The painted decoration of these vases is carried out in the technique that was universally employed by Attic potters in the latter part of the sixth century B. C. The figures of the painted friezes are done in black against the ground of the clay. Details are added in purple and white to give a gay effect. The undecorated portions above and below the friezes are painted solidly black, except in one case where a delicate ray pattern in relief lines takes the place of the more sombre black. The ridge below this frieze is further decorated with a band of ivy pattern. The purple and white colors have now largely disappeared. Purple was applied in bands to emphasize the horizontal divisions of the vase and to brighten dark surfaces. But more especially it was used within the painted design for rendering details such as stripes of garments, beards of men, the eyes of women, and fillets in the hair. White paint, very thick, is used for the flesh of women, for embroidered patterns of costumes, and other details. Incised lines cut through the decoration into the clay itself are employed to outline muscles, folds of garments and other lines which fall within the contours of the figures.

Museum Object Number: MS4846

Image Number: 2788

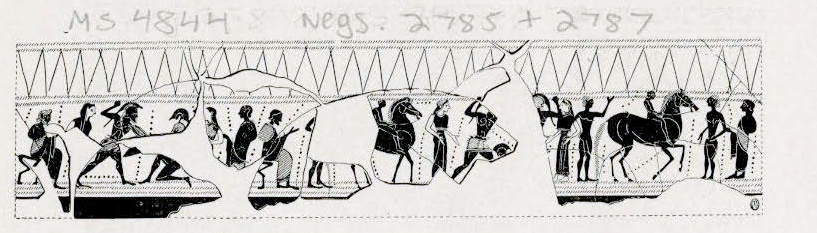

The subjects of the decoration of the bowls (Figs. 94 and 95) are those most frequently employed by artists of the black-figured style, the one a series of draped youths and maidens conversing, the other, a dance of maenads and satyrs. The lids are ornamented with horsemen, warriors and athletes (Figs. 96 and 97). The drawing, though lively, is careless in details; hands and feet are excessively long; the crowns of the heads are abnormally small; liberties are taken with eyes and noses. These peculiarities, as well as the general style of small and over animated figures and the choice of subjects, are characteristic of the atelier of Nikosthenes, who himself a potter, employed artists of varying abilities to decorate his vases. Especially striking is the resemblance of the galloping horsemen of Fig. 96 to those depicted on a narrow frieze of an amphora signed by Nikosthenes, in the Louvre. (Wiener Vorlegeblätter, 1890-1891, Pl. III, 2, c & f.) The association of these bowls with the work of Nikosthenes is thus supported by arguments of style as well as by the fact that Nikosthenes employed this unusual shape of covered bowl.

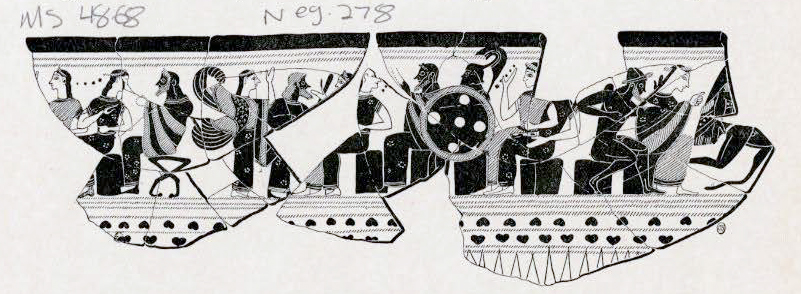

But far more interesting than these draped and dancing figures is the painted scene of Fig. 98. At a glance it is apparent that we are here in the presence of deities. The attitudes of the seated goddesses, who turn with animated gesture to the gods behind them, recall those of the seated gods who adorn the Siphnian treasury at Delphi. The scene is, therefore, of paramount interest, for it is only through vase-paintings like this that an idea can be gained of the early mural decorations and sculptured friezes of deities from which the Delphi frieze, and indeed, the pediments of the Parthenon, were eventually evolved. The majority of the figures are seated on box-like stools, only one stool with legs appearing to the left. The standing figures are the principal actors of the scene and toward them the looks and animated gestures of the others appear to be directed. The attention of the assemblage converges toward two points—the two standing figures, fourth and fifth from the left and the running figure on the extreme right. Here apparently the artist intends to give the clue to the story he is depicting. The despatch of the runner on the right indicates a stirring event of some importance. The upraised hands of the goddesses also bespeak excitement.

Museum Object Number: MS4844

In vases representing conclaves of deities, the two events which are usually depicted are the Birth of Athena and the introduction of Herakles to the circle of deities. The Birth of Athena is variously treated; sometimes Zeus is seated in the throes of childbirth, but no Athena is in sight ; again she is a tiny figure in the act of springing from his head, or, larger grown, she stands on his knee; or lastly, full grown, she takes her place beside Zeus and is welcomed by the other Olympians. The last three types are not represented, obviously, on this vase, since no Athena appears. But it is possible that the author intends to represent the moment before birth. In that case, the seated figure beside Ares in the center would be Zeus and the two goddesses before him, the Eilythuiae, or goddesses of childbirth. The despatch of the messenger on the right is, according to this explanation, somewhat premature. We have also to explain the absence of Hephaistos, who clove the head of Zeus open. Herakles is frequently depicted as present at Athena’s birth, and as a newcomer among the gods it is perhaps natural that he should not be seated. The presence of Nike or Iris is entirely appropriate to the scene.

The other event commonly depicted in conclaves of deities, the introduction of Herakles to Olympus, is a less likely interpretation of the scene depicted here. For, although Herakles occupies a central position (fifth from the left), and stands next to Iris or Nike, he is unaccompanied by his patron goddess Athena, who invariably presents him to Zeus and the other gods.

The scene is the more interesting because it does not conform closely to conventional types. If an explanation can be found which suits the figures exactly, it will add to our knowledge of the repertoire of early vase painters, and in the meantime the vase at least affords a new arrangement of a frieze of seated deities.

E. H. D.

Museum Object Number: MS4868A