THE old English floor tiles made at the beginning of the 13th century and as late as the 16th century have often been admired on account of their simplicity and practical utility. This is because the material and glaze make them better adapted for use underfoot than the . contemporary majolica tiles of Southern Europe. Their simple decoration is also well adapted to flooring. The best examples are to be seen in a series in the British Museum found on the site of Chertsey Abbey.

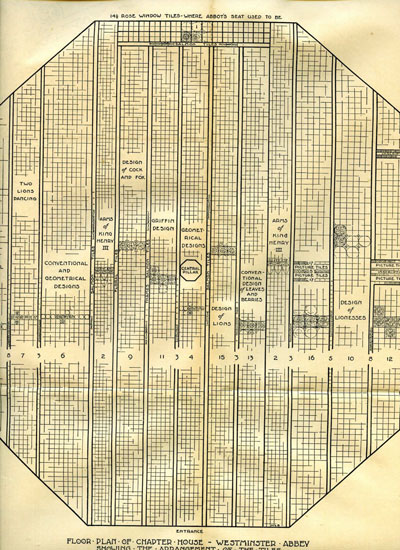

Visitors who enter the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey can hardly fail to notice the floor that presents a most interesting appearance and that is made up of several series of tiles of the same kind and date as those found in Chertsey Abbey. The part of the floor that you walk upon is covered with linoleum and the tiles are therefore hidden but in the central area that is railed off the tiles may be seen.

In 1237 it was ordered that the King’s “little chapel” at Westminster should be paved with “painted tiles.” Whether or not the tiles then ordered to be made are the same as those at present in the floor of the Chapter House cannot be discussed here, but it may be remarked that it is not unreasonable to suppose that the tiles now in the Chapter House may have been removed from another place to their present position. It is certain that they were made early in the 13th century.

These Westminster tiles have never been published and none of the books on the Abbey give a plan of the tile floor of the Chapter House or have much to say about it. Yet it is interesting for its design; it is an instructive study in tilework and it has the extraordinary historical interest that it was the pavement on which the first of all parliaments, the first House of Commons, looked down. From their seats on the stone benches around the walls where the monks of Westminster had sat before them, the members of the first House of Commons may have found entertainment in puzzling out the varied pattern of the floor wile some fellow member was speaking. In the course of time when the Chapter House was converted to other uses, a wooden floor was laid down over the tile pavement and the tiles were forgotten. In 1840 it happened that the boards were removed and the old tiles were revealed beneath.

This kind of tile is for some reason commonly called encaustic and the method of making was as follows. A common red clay of England was mixed and pressed into a mould that had carved upon its surface the design that was to appear on the tile. When the clay had set but was still damp and plastic it was taken from the mould and a white pipe clay was spread over its surface to fill the impressions made by the mould. The whole was then smoothed off, leaving the design in white or cream on a red ground. Powdered galena was sprinkled over the face of the tile which was then finished with one firing. The qualities inherent in these tiles which commend them both for artistic effect and for practical use are the simplicity of the process of manufacture, the common materials of which they are made, the natural lead glaze and their resistance to wear.

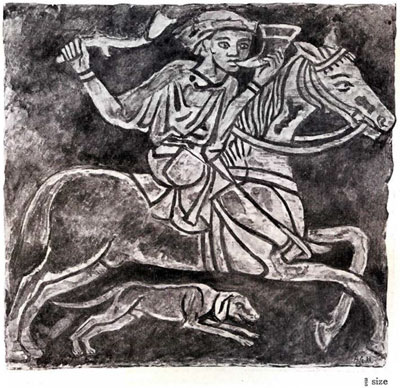

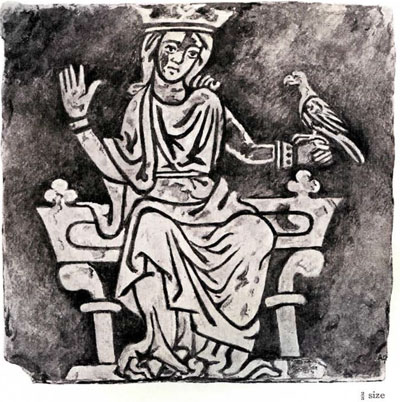

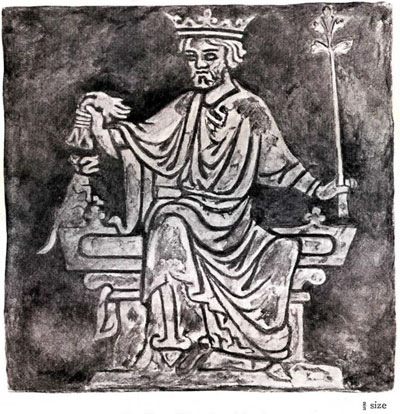

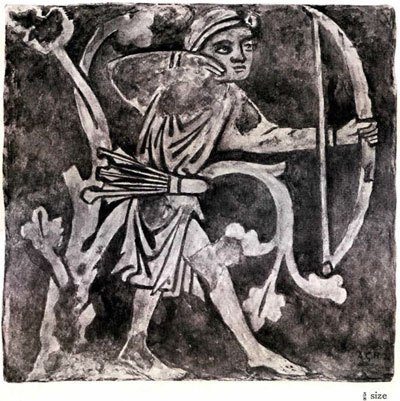

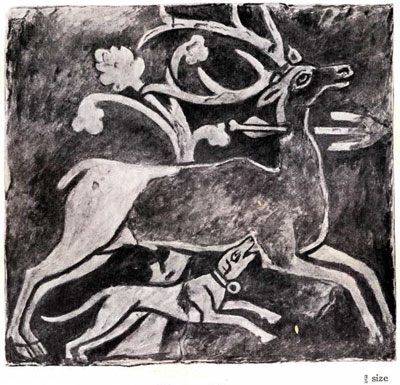

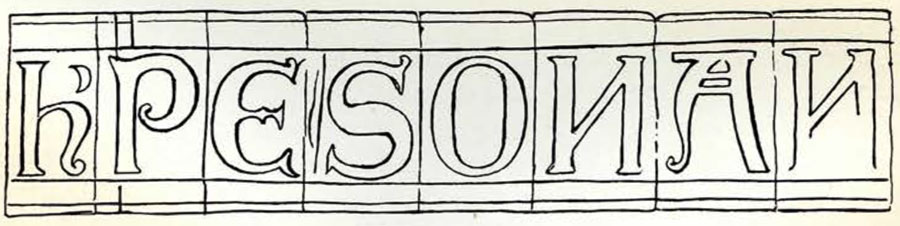

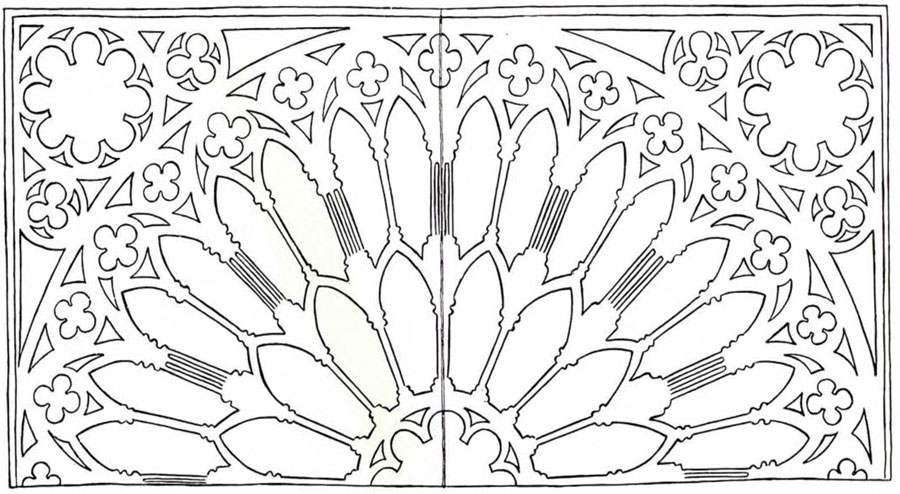

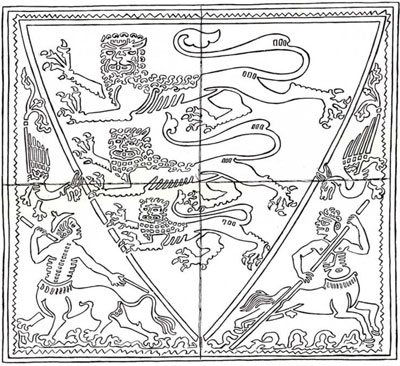

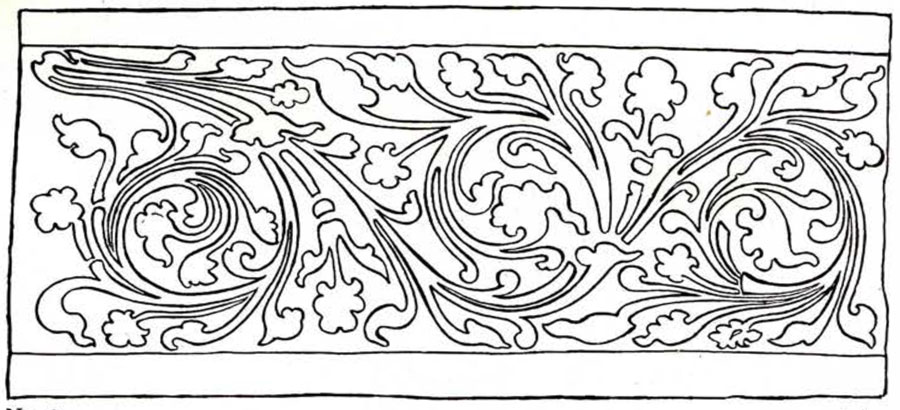

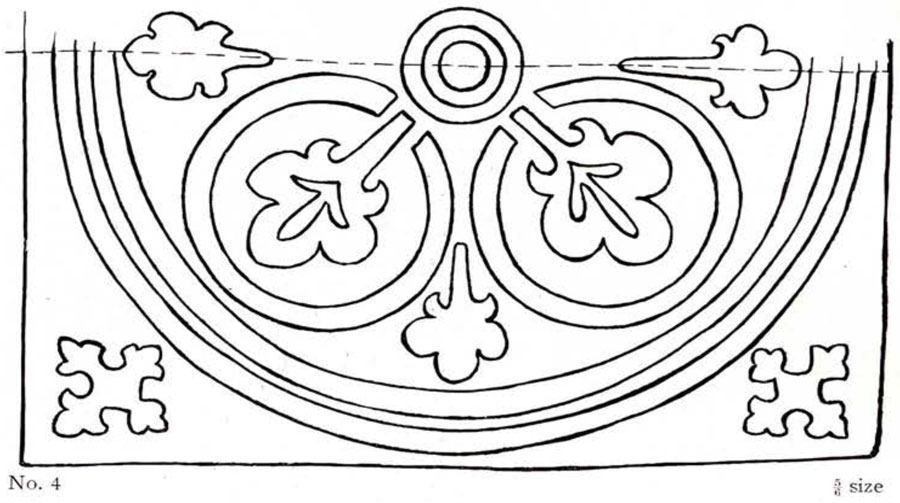

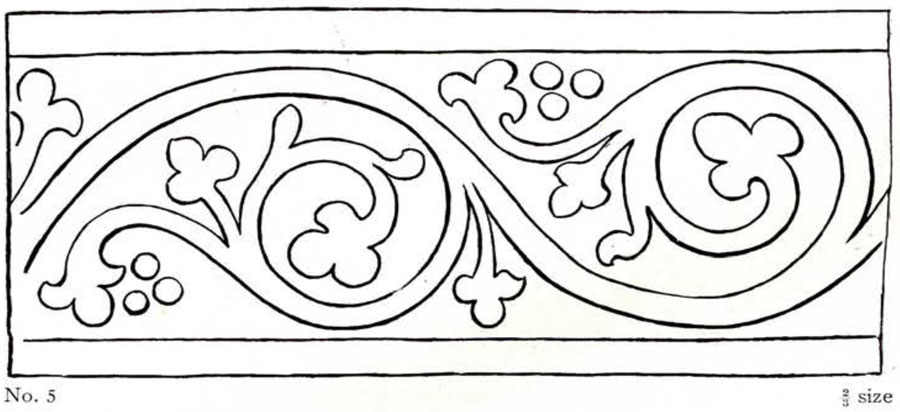

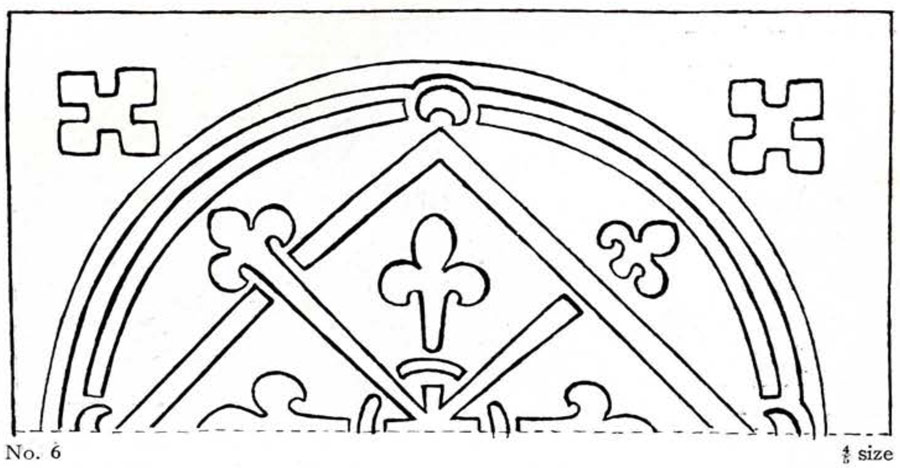

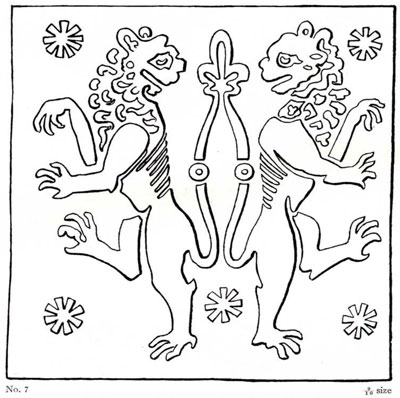

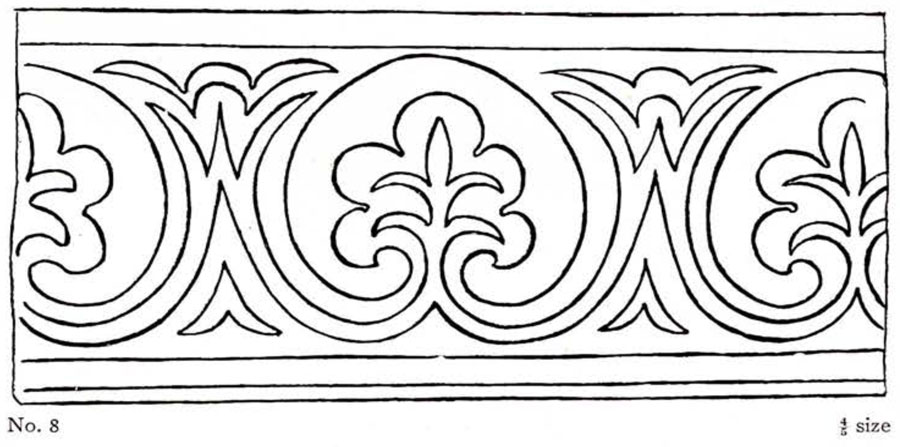

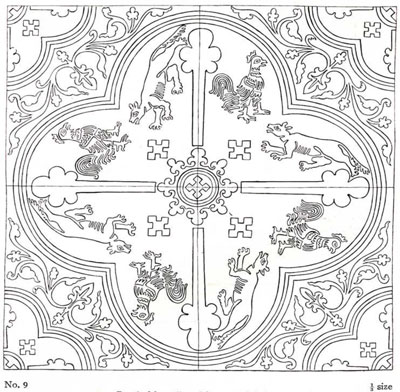

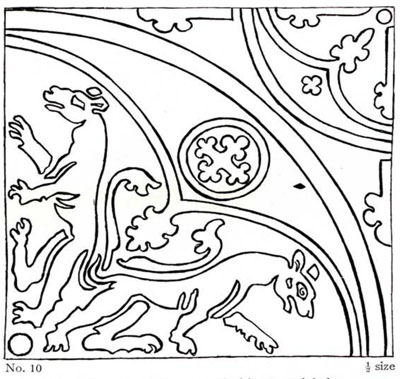

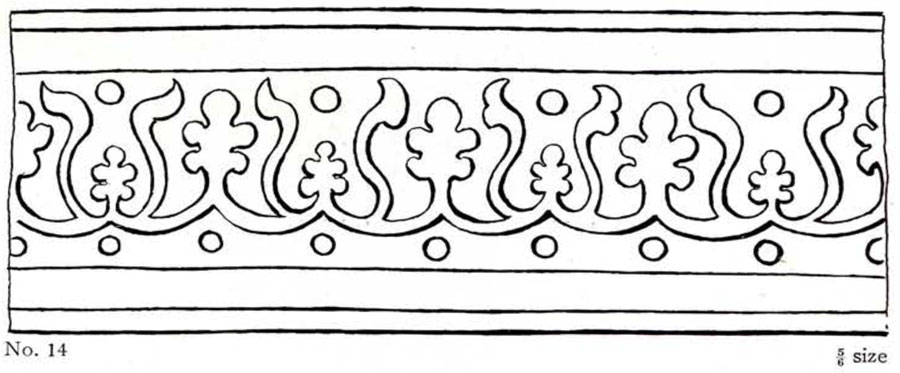

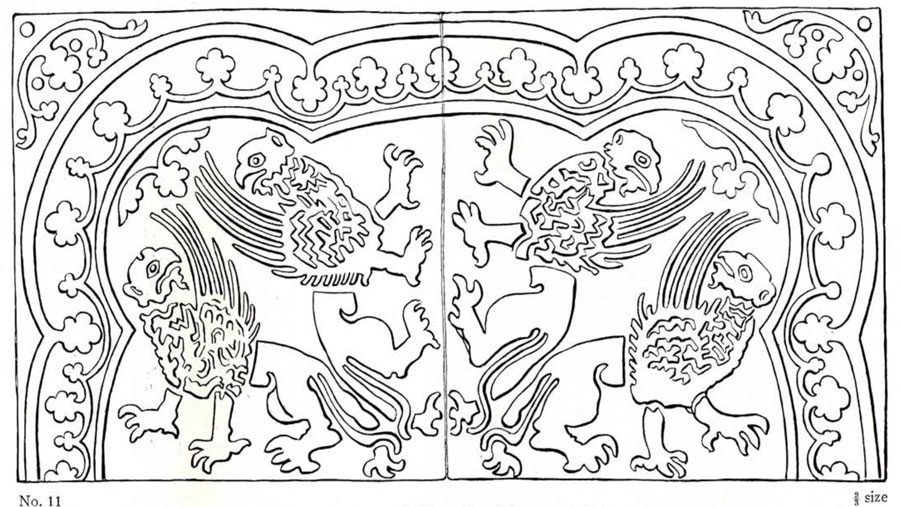

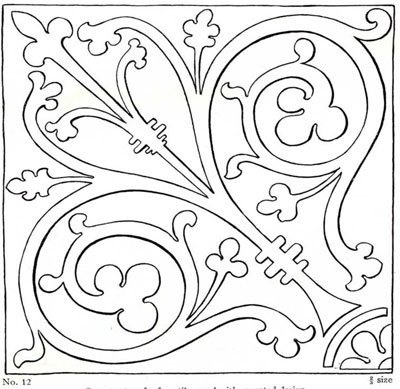

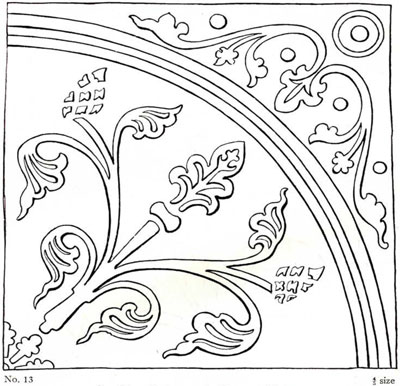

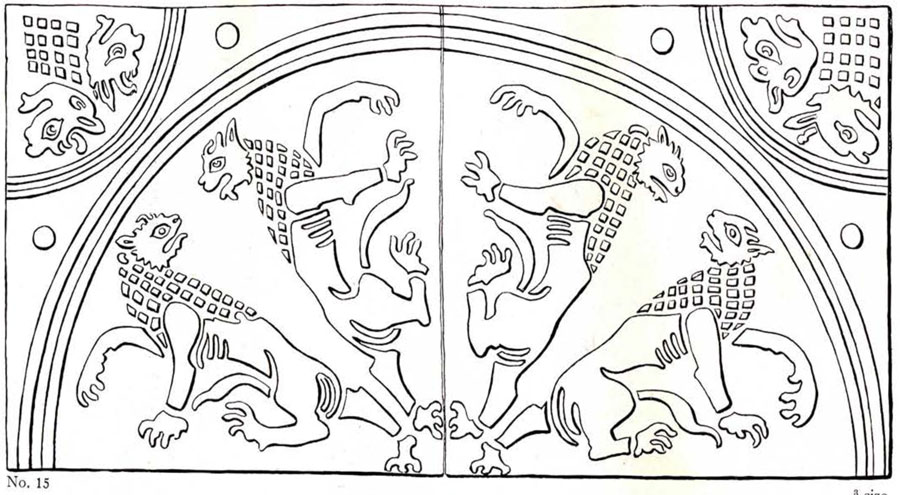

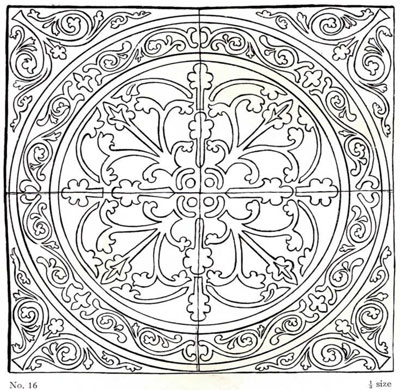

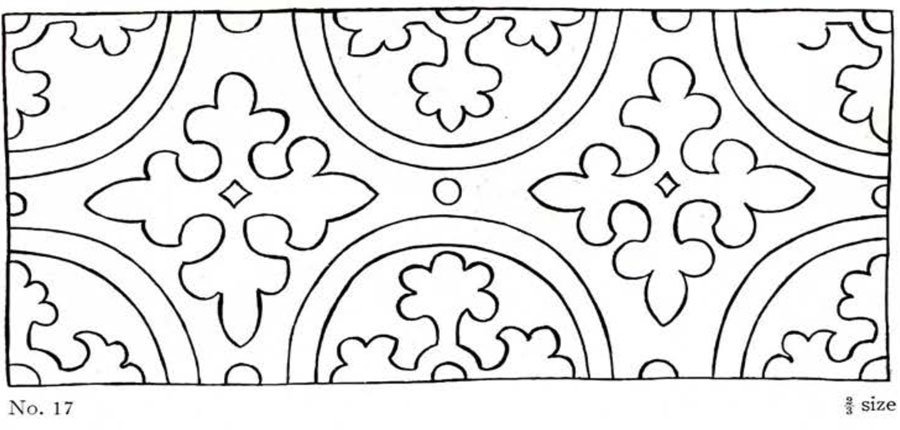

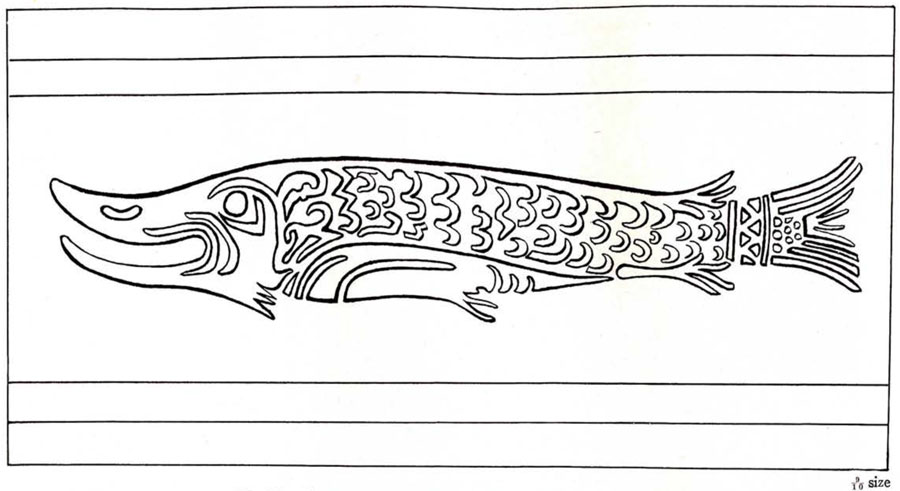

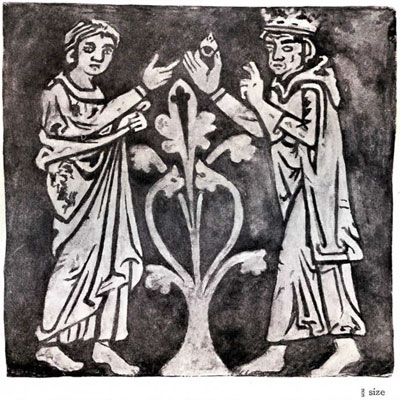

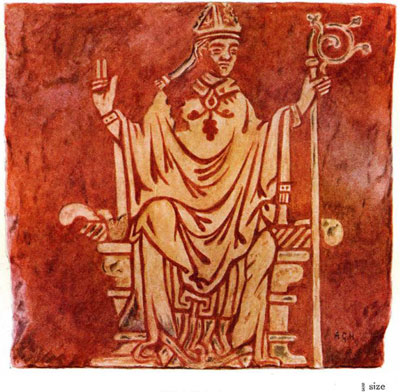

The arrangement of the tiles on the floor of the Chapter House is shown in the diagram opposite page 290 and the designs of all of them are shown in the illustrations here reproduced. The most curious features of the floor is the presence of two groups of picture tiles comprising twelve tiles each but as the subjects are repeated the number of separate designs is reduced to eight. They are arranged in the following order. Group nearest the pillar, Upper row, 1-2-3-4-0-1. Lower row, 1-2-3-4-5-1. Group farther from the pillar, Upper row, 2-3-4-3-5-3. Lower row, 6-7-8-6-7-8. The numbers refer to the designs as shown in our illustrations. The zero in the first series means that another tile has been inserted and that the row of six picture tiles is interrupted at that point. The subjects in turn fall into two groups. One may be called court subjects and the other hunting subjects. In our illustrations one tile is reproduced in colour. The colours in the others are of course the same though they are shown here in black and white. The King, 5, is surely a portrait of Henry III. This can be recognized at once by a comparison with his effigy on his tomb in the Abbey. The broad forehead, the wavy locks and the short curling beard are common to the effigy and the picture tile and serve to identify the picture as that of Henry III. The Queen, 4, therefore can be no other than Eleanor, his wife. In such a group one would expect the Abbot to be Crokesley, who was appointed by Henry. The group representing the legend of Edward the Confessor and the beggar is curious. A strong tradition represents Edward with a long white beard. A picture of him on a Sedilia preserved in the Abbey shows him with a long beard and so does the contemporary Bayeux tapestry. In the tile the face of the figure representing the King is beardless and in fact the face and figure are not those of a king but of a monk. It is simply a monk wearing a crown. The only explanation I can offer is that it was the custom of the Abbey to present the story of Edward’s life in the form of a play in which the characters were impersonated by the monks. The part of the King would be taken by a monk whose resources in a makeup consisted of a crown, the one thing essential. The tile maker, himself probably a monk in the Abbey, had this impersonation in mind when he drew the picture for this tile. On the site of Chertsey Abbey underneath a garden there has recently been discovered a kiln in which tiles were fired, an indication which suggests that tile making was localized in the monasteries.

The admirable drawings here reproduced were made by the well known London artist, Miss Annie G. Hunter, whose helpful memoranda I wish also to acknowledge. I am indebted to the Dean of Westminster for permission to have the tiles drawn and for his kindness in facilitating the work. The plan of the floor has been drawn by Miss M. Louise Baker after sketches and notes by Miss Hunter.

The numbers under the line drawings agree with numbers written on the floor plan.

Image Number: 22681