To the Head Waters of the Amazon

After returning from the Guianas, we made a journey of 2,200 miles up the Amazon River in an English ship to Iquitos, Peru. The first night after leaving Para, while threading our way among the numerous islands, we ran aground on a sandbar and were unable to get off. A larger ship belonging to the same company went by but could not come near enough to assist us. There was no danger whatever as we were out of the current and had only to wait for the returning tide to carry us over. The islands are often very large and one does not realize that the ship is not running along the mainland. To avoid the current, which runs at about four miles an hour, the ship always remains near the land on one side or the other. If one takes the trouble to climb the mast and look over the tree tops he will more than likely see beyond the narrow island another branch of the river as large as the one he is traveling. There may be three or four branches each of which is several miles across. The lower river is like a great funnel a hundred miles across which narrows to the neck at Obidos five hundred miles up where it is less than a mile and a half in width. Here all the water is confined to one channel which is said to be two hundred and fifty feet deep.

Image Number: 27973

The tide is felt about four hundred miles, and the water actually flows up stream for two hundred miles. The side streams also feel the tides for a long distance. Even where the Amazon rises but continues to flow it dams up the other rivers and causes an upstream flow. For example: we were traveling by canoe up the Amazon on the north side of the river when the tide was in, but the water was still running out. When we reached the mouth of the Jary’ we were paddling against a strong current, but when we turned into the Jary’ we floated for several miles up stream. The sea water does not go far inland, yet with a strong wind at high tide we found the water too salt for making coffee at a distance of seventy-five miles from the sea.

The land along the tide part of the river is too low to be used for agricultural purposes, hence there is no cleared land. The rubber gatherers live in small houses on stilts and make no clearings. One traveling along the river for the first time has a feeling that the people have just arrived and have had no time to make fields. But it is just as it has been for a century and just as it will remain for another one. About three hundred miles up river you get the first view of a range of low mountains through which the riverappears to have cut its way. Many of the mountains are covered with grass and support hundreds of cattle and horses. Around the foothills there is much cleared land where cassava, sugar cane, corn, bananas, etc., grow luxuriantly. When this high land is passed there is nothing to break the monotony of the broad flat expanse until the snowcapped Andes appear in the far distance. There are slight elevations at many places which give a location for small villages and fields.

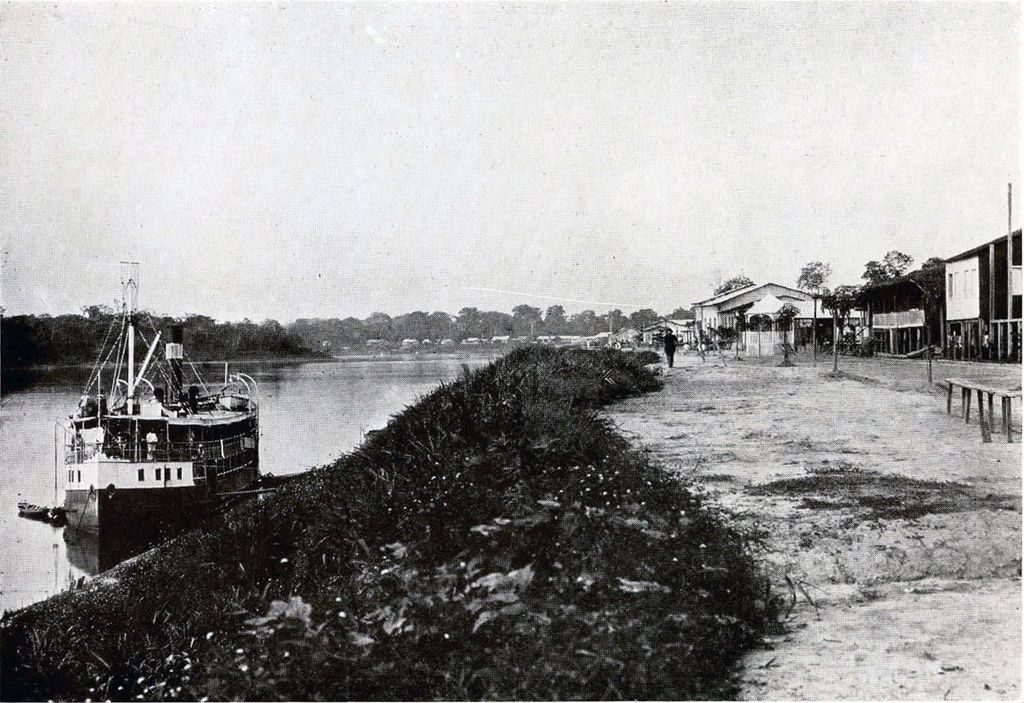

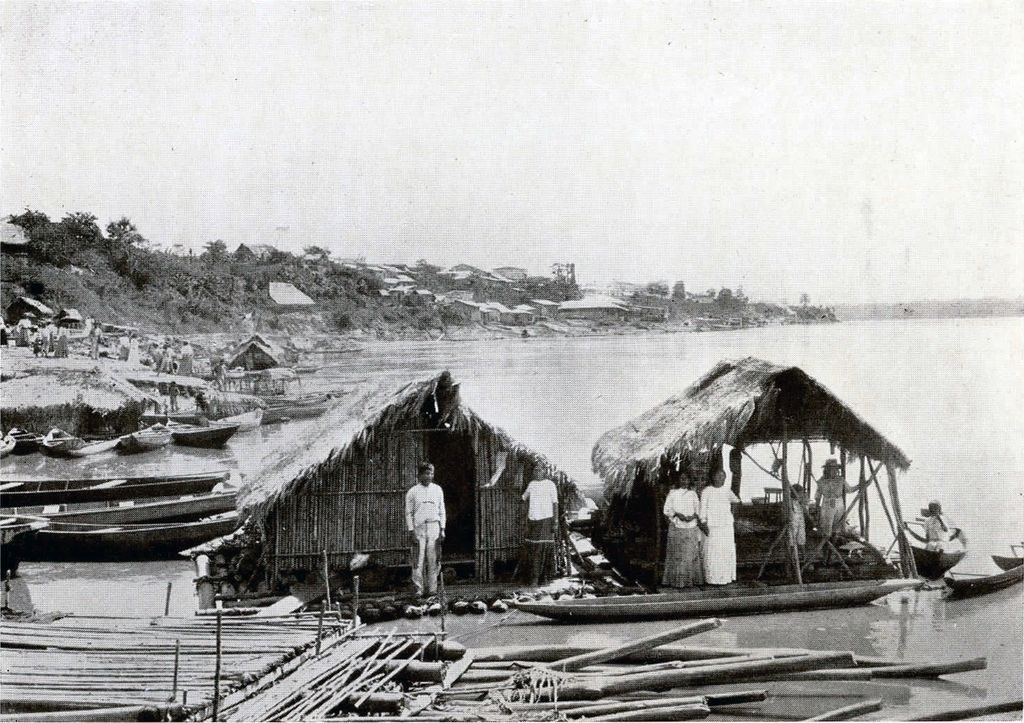

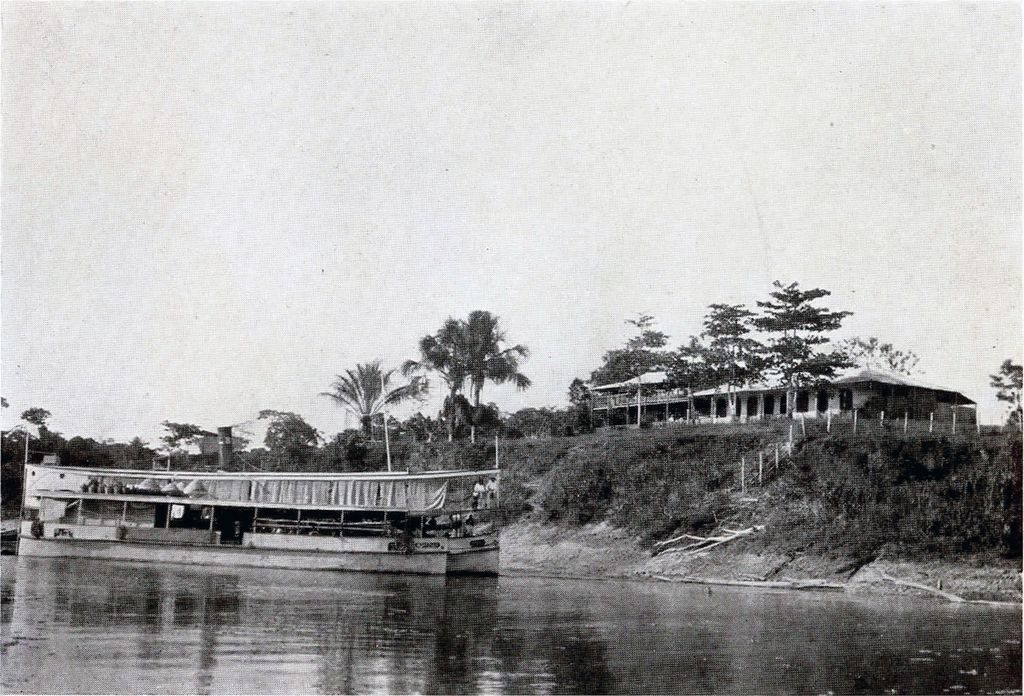

Our first stop was at Manâos, nearly a thousand miles from the sea, where we spent a day and took on several passengers for Tabatinga, at the boundary of Brazil, and for Iquitos. Among them was a Peruvian government official, who had been sent three months before from Lima to take his post at Iquitos. He had gone up the coast to Panama, then to Barbados, and from there to Manâos. After spending seventeen days more he reached his station eight hundred miles from the Capitol.

Image Number: 28178

Manâos, a thriving city of 80,000 inhabitants, is on the north bank of the Negro a few miles from the Amazon. The water of the Negro is very dark, while that of the Amazon is yellow. Where their waters come together a distinct line is seen for some distance, but gradually the Amazon color predominates. And so all the way to the sea: the Trombetas, the Madeira, the Tapajos, the Xingu, the Tocantins, the Paru’, the Jary’ and numerous smaller rivers bring their clear waters to the Amazon only to be swallowed up without noticeably changing the original yellow of the great stream. The Amazon is never clear, not even in the dry season. It is difficult to appreciate the great volume of water carried by the Amazon during the rainy season. The flood plain extends for many miles on both sides of the river, yet it rises some fifty feet at Manâos and forty feet at Iquitos. Lower down where it meets the tide the rise is not so great. At Para, the difference between high water with incoming tide and low water with outgoing tide is about fifteen feet.

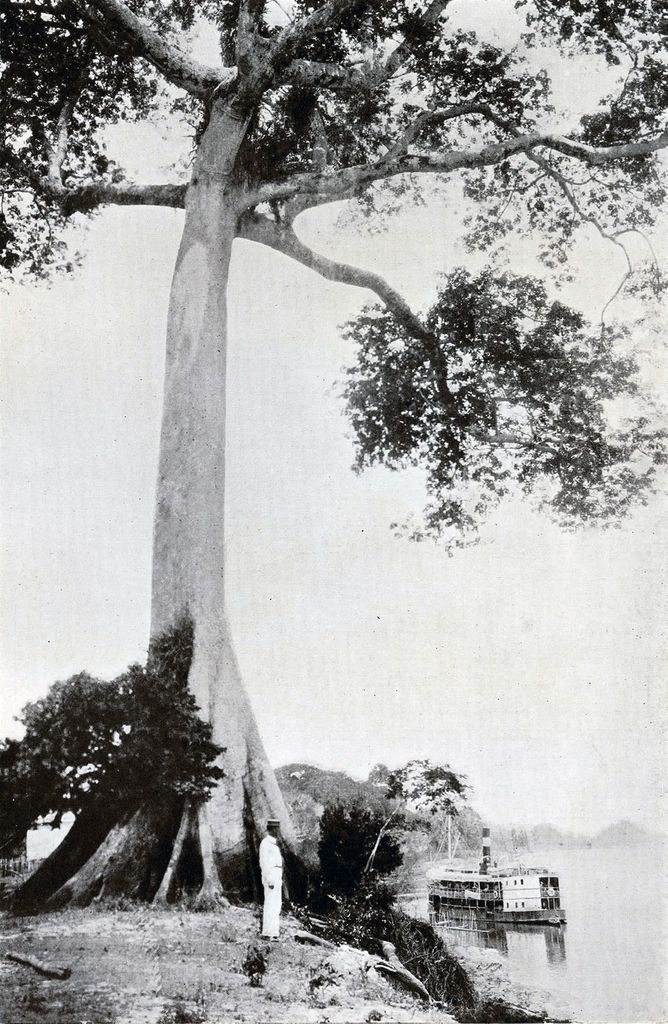

Besides carrying sediment the river carries great quantities of logs and trees out to sea. The trees that fall into the upper rivers are soon broken and stripped of their branches. They collect in eddies and are piled high with other driftwood on the sandbars: Great cedar logs thus piled up and cured were used by the Indians in making their canoes. Often whole trees with other drift get out into the current and are carried down like a great island. One night our ship ran into such a floating island and was compelled to back away to get free from it. Damage is often done to the propeller in this way. The heavy hardwoods will not float and they may be seen at low water lining the banks where they fell. The small launches have much trouble in the shallow streams on account of running on top of these logs. It is much more difficult to get free from a log than from a sandbar.

As we were ascending the river in the dry season it was necessary to take great precaution. The channel is constantly shifting. Where a ship passed in safety last year, a large canoe may not be able to pass this year. The native pilots are experts in determining the depth of the water from the appearance of the current. The greatest danger is near the mouth of a large tributary. The cross currents which are interfered with also by numerous islands cause deposits in unexpected places. Before we reached the Brazilian boundary we were having so much difficulty in locating the channel that it became necessary to tie to a tree at night and run only in the day time. This gave us an opportunity to go fishing. At the Peruvian frontier we were met by the Booth Company’s tugboat which ran ahead and located the channel for us.

Image Number: 28181

A short distance below Iquitos we met the English consul in a motor boat, coming to notify us that war had been declared in Europe the day before. When we arrived at the city we found considerable excitement. The two banks, one English and the other Peruvian, were closed but all the drinking places were doing a good credit business. Everybody talked war. Some Frenchmen and Englishmen took the first opportunity to go home and volunteer for service. Several Germans took passage on a launch belonging to one of their number and went down to Manâos, where they learned that it was impossible to get home, so they returned, after a short visit.

As we had no money and there was no possible way of getting any we were unable to go to the hotel. The Booth agents took care of us until we could get away some weeks later.

At such a time one appreciates friends and the credit system which is the common method of doing business throughout the rubber region. We had expected to spend several months in study and collecting among the different tribes of Peruvian Indians, but that now seemed impossible. I had been in Iquitos eight year before and had made a two weeks trip with the manager of the Barnard Rubber Company on one of their launches up the Ucayali River. Fortunately this same man was in charge of the business again after a long vacation in Europe. I called and related my difficulties. He said, without any hesitation or questions, “That is easy, within a few days I must go to Cumaria (the head of navigation on the Ucayali) to collect rubber, I will furnish you passage and all the goods you need for trading with the Indians and allow you to pay when you can. ” I availed myself of his very generous offer and spent some six weeks with him on the journey. He did even more than he had said he would do. He stopped at every Indian village and every place we could hear of a specimen. He often went with me in a motor boat up small streams while the launch loaded or waited below. We made over two hundred calls on the round trip and collected specimens from the Campas, Cashibos, Conebos, Piros and Shipibos. The large collection of Conebo pottery is unique and one of the best of the whole expedition. The Conebos make the finest pottery of all the tribes and their wares are found among many other tribes as well as in the homes of the whites living along the river. In the collection are “chichi” pots, for native drinks, three feet high and four feet across the body.1 These were carried suspended from poles on the shoulders of men to the river, there they were placed in canoes and taken to the river launch which carried them to Iquitos, where they were packed and sent direct to New York by a Booth steamship. A part of the collection was presented to the Goeldi Museum at Para upon our return.

Image Number: 17814

At Cumaria, the last station up river, we met many canoes from farther up stream and from the side streams, bringing rubber to the launch. Here we found some most incongruous combinations of primitive with modern methods of navigation. For example, we saw a dugout canoe fitted with an Evinrude gasoline motor and used by a Conebo Indian to bring rubber from the small rivers to the station.

As it was impossible to learn anything about money affairs up river, it was necessary to make such a rapid journey that no time could be given to ethnological study. After an absence of six weeks we returned to find no improvement in the financial situation and it was, therefore, necessary to return to Para. There was not a cent in circulation. To make matters worse, freight rates were doubled at once and exporters could not afford to ship their rubber, or vegetable ivory nuts, the two important exports. The monthly service of foreign ships was reduced to one ship in three months and when it came it could not carry the food stuffs required for the people. As a result, many were compelled to leave the city and go to the upriver plantations, leaving their unpaid bills behind.

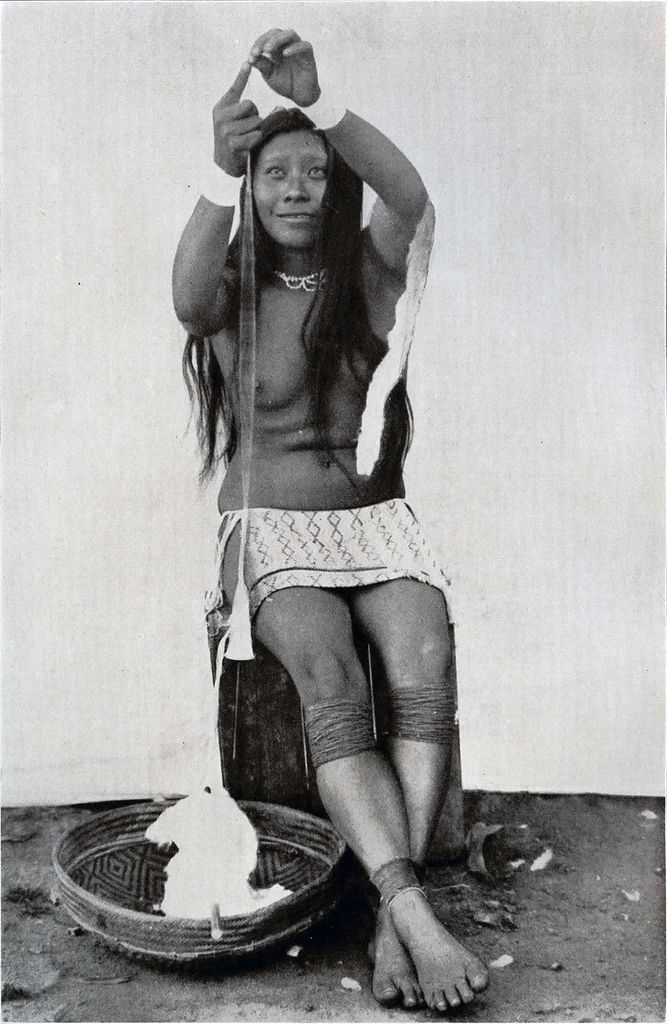

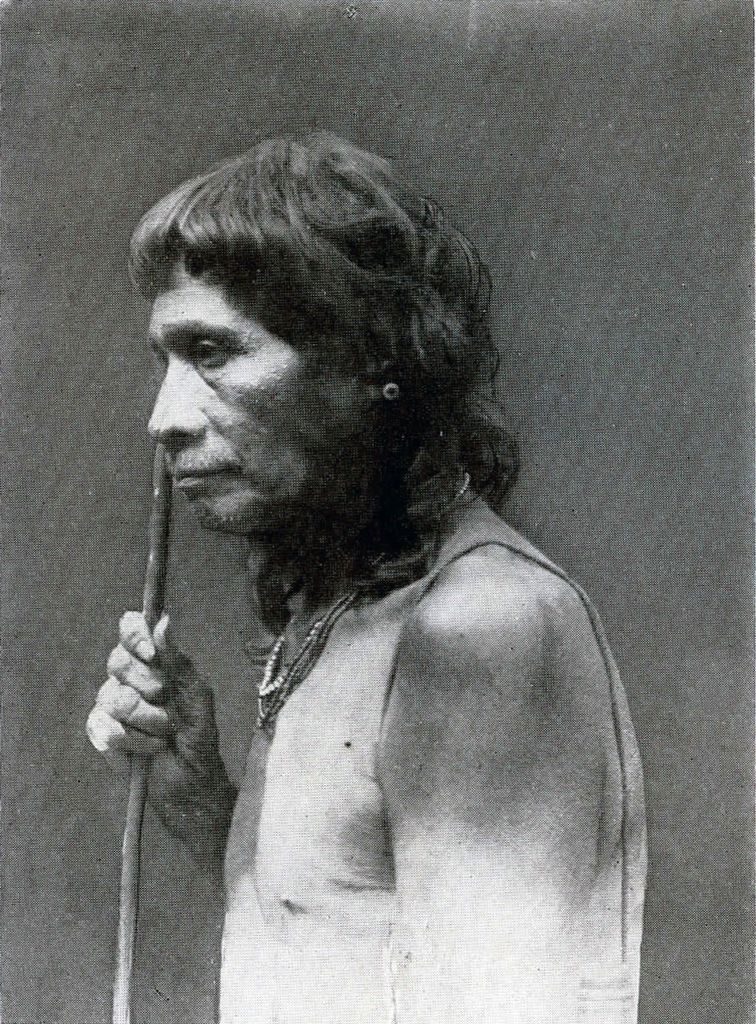

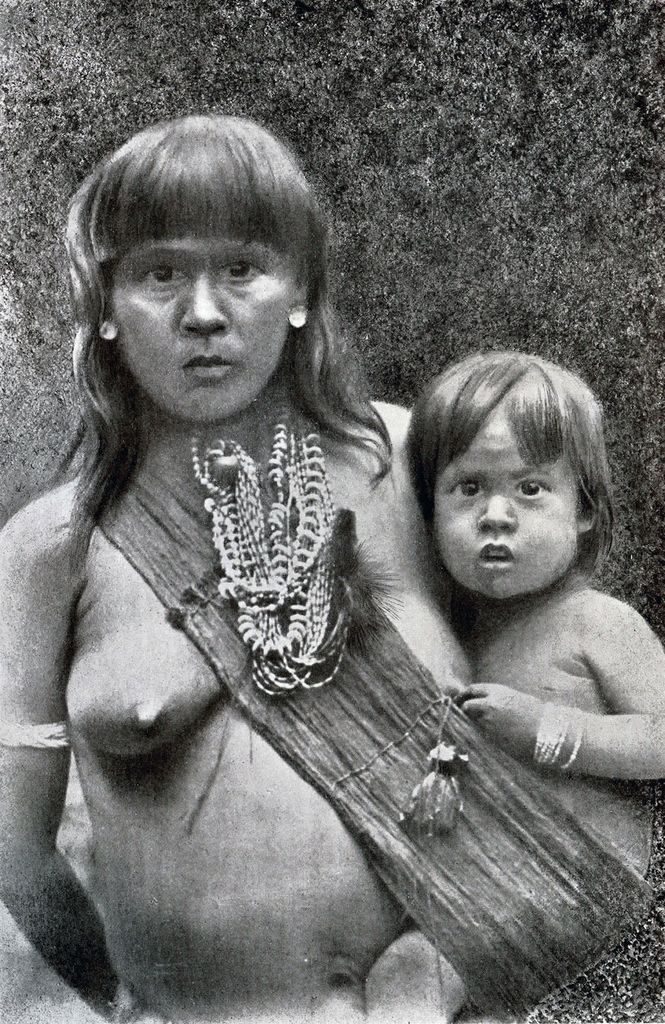

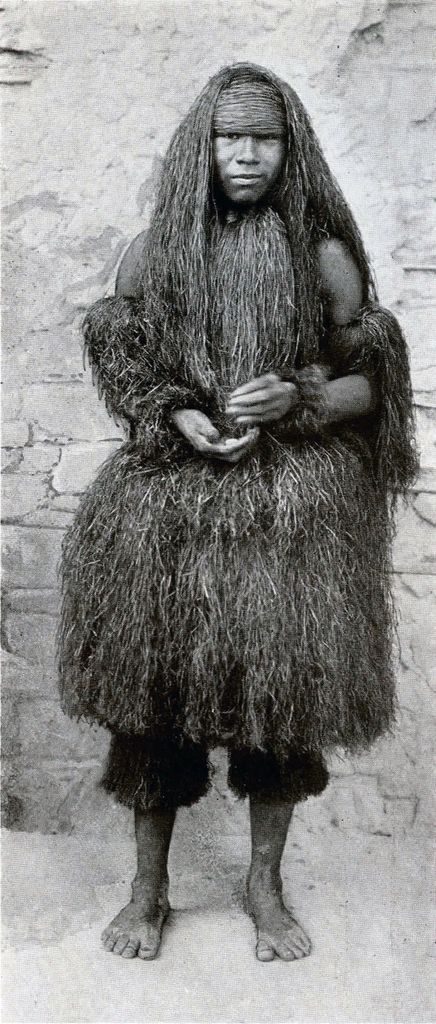

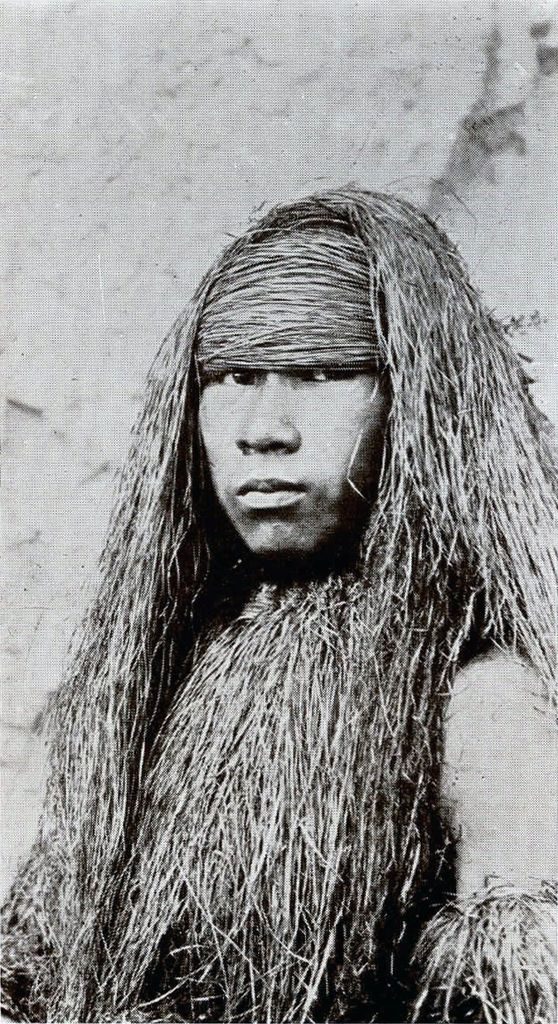

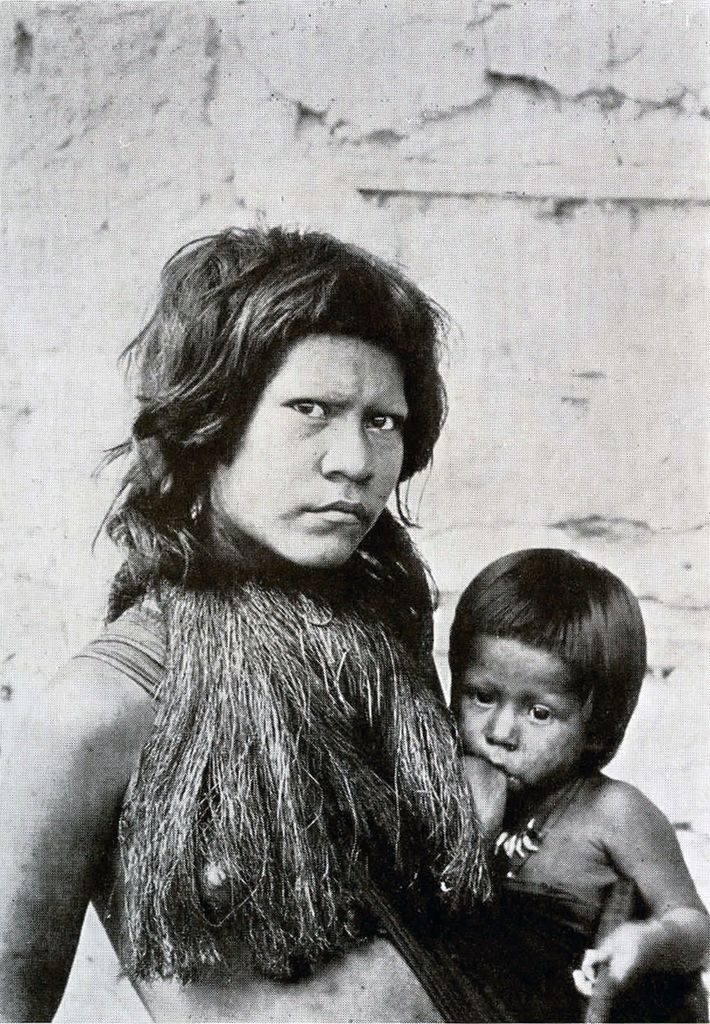

Image Number: 17895, 140880

With such a state of affairs it was impossible for us to continue our work, so we started down river, stopping on the way to visit the Yahua Indians. We made a good collection there, and paid for the goods we used in exchange several months later. Although this tribe has been in constant contact with civilization for two hundred and fifty years, and during most of that period has had a mission station, the members of the tribe speak their own language only, dress in grass, and practice their ancient customs and religion. As no one at the mission spoke the Yahua language, we were unable to learn much of their customs or beliefs. Only a remnant remains of the large group that once made up this tribe. It is the same old story, such contact with civilized men serves only to destroy primitive peoples. In a few more years they will have disappeared.

In addition to the ethnological collections, we sent also from Peru a number of live birds and animals for the Philadelphia Zoological Gardens, consisting of parrots, maroudis, curassows, orioles, bitterns, monkeys, cutias, pacas, squirrels, jaguars and a tapir. The Sun parrot is the most beautiful of all the family. “He spreads his neck feathers in a flaming glory around his head.” I carried him on foot for seven days and in the canoe and on launch for two months. One of the jaguars was a great pet and was allowed to run about the launch at will. The tapir was about three months old and still retained the white stripes which are characteristic of the young. The tapir is extinct in all the other parts of the world except in southeastern Asia and South America. It is a curious fact that the young in these widely separated areas are alike in color while the adults are quite different in this respect.

The Peruvian launches go to Nazareth on the Javary River, the boundary between the two countries, for purposes of trade with those living on their side of the river. The Brazilian launches stop at Remate de Males on the opposite side of the river. These two villages are the wet season centers for upriver rubber gatherers. Here they loaf and enjoy themselves until the rains cease, when they must go to work again. This location is a convenient one in which to live, because one may take advantage of the different customs duties in the two countries—at night. From this place our launch carried many tons of rubber and on the way picked up six hundred live turtles for the market at Manâos. Beef is scarce there, except for a short period, when cattle are received from the savannahs of Rio Branco. Many cattle are raised in the low grass lands along the river but not sufficient to supply the market. These turtles are caught on the sandbars at night, when they come out to lay their eggs. The people rush out from their hiding places and turn the turtles over on their backs. In this position the turtles are helpless. They are next carried to pens and kept there until a launch arrives to carry them to market. The turtles average about seventy-five pounds each, and sell for five dollars apiece. Our passage, as stated upon going aboard, was to be fourteen pounds sterling, or, at the last known exchange, two hundred and ten milreis; but when we arrived at Manâos, we paid three hundred and twenty-two milreis, or a difference of more than fifty per cent, due to the depreciation of Brazilian currency, on account of the European war. Upriver prices for the most part remained the same, but in the cities the prices increased to keep pace with the depreciation of milreis. The increased cost of imports and freight rates, and the decrease in value of exports and currency made times hard in the valley. Laborers in the cities could not get work, and many moved to the islands, where they lived on farinha and the flesh of the capybara, the largest of the rodents. A boy I had employed on my first trip came back and begged for work again at less than one third of his former wages.

Image Number: 17901

We soon learned to make farinha our principal food, supple. menting it with whatever meat we could get along the rivers, or in the forests. Farinha is the coarse flour made by the natives from the root of the cassava plant. It is used by many of the Indian tribes as well as by all the Brazilian rubber gatherers. The root cannot be used as a vegetable because it is poisonous. Farinha is obtained by grating the root, pressing out the poisonous juice, then roasting the remaining pulp in an open oven. While not palatable, farinha is a very nourishing food and may be eaten as it is, or mixed with soups, tea or even cold water. For the traveler in that region it is the best possible food to carry. It keeps indefinitely and may be procured from any rubber station or Indian village.

Instead of roasting the pulp some of the Indians use it in making coarse bread. On the higher land there is a variety known as sweet cassava, which is not poisonous and may be eaten boiled or roasted.

The Purus

During the rainy season, which lasts from four to six months according to the location, it is difficult to travel in the interior because the rivers overflow their banks and make it impossible to go on foot. It is also a bad time to travel by canoe because there is no high land for camping places, making it necessary to pass the night in the canoes. At such times it is necessary to cook aboard the canoe. The stove in all the canoes along the Amazon is made of a Standard Oil kerosene tin. Three inches of earth is placed in the bottom to prevent burning through. Just above this a hole is cut in one side for the fire. The top is removed and the cooking pot suspended inside. It is cheap, convenient and efficient. Two kerosene tins are shipped in a strong wooden box. These boxes serve as seats in all the rubber men’s houses. There are no chairs in the region outside of the towns. Everybody sits or lies in his hammock and has little use for a chair. In well-to-do homes an extra hammock is kept for the use of visitors. Little or no food can be obtained on the way. The land animals go to the higher places away from the rivers and one cannot go into the forests for birds or monkeys. Fish cannot be caught in the rivers because they go into the forests to feed. On one occasion we killed a great many fish weighing from four to five pounds each, with our machettes in shallow water among the trees. The Indians who live along the river in the dry season, usually have homes and fields on high land far away, where they retreat during the rainy season. Without a guide these places cannot be found. On one of the rivers we learned that a tribe had a village three days journey on foot from the river in dry weather. They had no canoes and never came outside while the water was over the trail. When we asked the rubber gatherer, who was living in a house on piles, if it was possible to reach the Indians, he said there was no land one could put his foot on within a hundred miles in any direction. We attempted to follow the trail through the woods in a canoe but could not find our way. Then we tried following a small stream, but soon came to a great lake with no streams coming into it. That is, the streams were so small and so winding that the branches of the trees met and left no trace of a channel. There was water everywhere but no passageway for a canoe. We had marked the trees on the way or it would have been impossible for us to follow the same way back to the river.

Image Number: 17898

The wet season begins earlier at the south and travels slowly northward. In order to take advantage of this fact we went up the Punts river, a southern affluent of the Amazon. At this time the river is navigable for more than a thousand miles of its course, to the very frontiers of Bolivia and Peru. It was the time of the greatest rainfall along the Amazon, and for half the distance up the Purus the water was over the banks and flooded the forests for many miles in every direction. The mules, which are used in the dry season to carry the rubber from the distant camps in the forest to the river, are kept on platforms built for that purpose during the four months of the wet season and are fed on wild grass cut along the river bank by men in canoes. In some places, as at Huytanahan, on the Punts, the vampire bats are so numerous and so bloodthirsty it is impossible to keep horses, cattle or even chickens. We are accustomed to think of the vampire as a myth. No doubt it is because the vampire of the ancients was a ghost that came at night to suck your blood. After one of these bats had taken his supper from my great toe, I was quite sure he was no ghost. In the morning my feet and my clothing were covered with blood, but I had felt no pain. Just how he is able to make such a deep wound without disturbing his victim, is difficult to understand. His favorite spots for operation on man are the toe, the nose or the temple, and on the horse the withers. The wound leaves a scar as deep as a pox mark. He is not the large bat as is supposed, but of medium size and easily distinguished by his teeth and stomach. He eats no solid food.

When the middle river is over its banks the head streams are already dry. The country is so very flat that when the rains cease the water away from the rivers remains to be evaporated. The water of the rivers soon runs out and leaves them unnavigable even for canoes. At Senna Madureira, the head of navigation, within three weeks from the time the river was over its banks it had dropped fifty-five feet and would not rise again until the coming of the next rains. Small launches caught at such times must remain for five or six months.

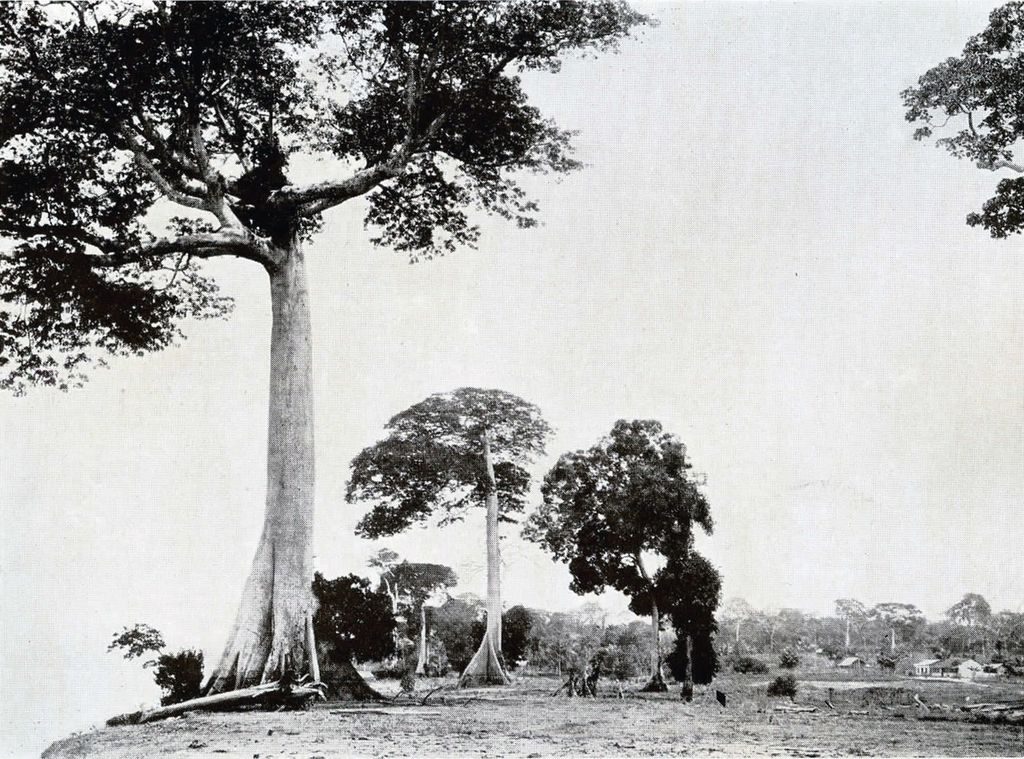

Senna Madureira is the capital of the Acre Territory and is connected with the other districts by wireless. The first people went to the Acre in 1877, but now the population of the Territory is estimated at 30,000. The town has a population of 1,500 during the rainy season and 800 the rest of the year. It has electric lights, tram cars, good schools and a college. A few years ago the government established an agricultural experiment station here with all kinds of machinery and tools, but it was soon abandoned. The people will not adopt agriculture as long as rubber gathering is profitable. The sawmill and planing mill were set up but were never in use. The houses are built of lumber from the United States, which has been shipped 2,600 miles through Brazilian forests. The forests are very dense with underbrush and small trees, but large trees grow far apart. One wonders why there are so many young trees a foot or less in diameter and so few old ones.

The Rubber Industry

Image Number: 17898

The rubber is collected during the dry season and shipped down on the high water. In former times the collectors had little communication with the outside world during the gathering season. Because of this they were often taken advantage of by traders who came up to buy their rubber. Now, however, there are several wireless stations in the interior, so the collectors learn the general news and, what is of more importance, the price of rubber. In 1912, before the time of the wireless stations, the owners of large “seringaes” took their rubber to Manâos in their own launches. They expected to receive six milreis a kilo, at which price they would have a reasonable profit. But to their great surprise they got sixteen milreis instead of six, and found themselves suddenly made millionaires. Little wonder that many lost their heads and spent their money lavishly and foolishly.

The life of the rubber man in the forest is not one of great hardships, as is often depicted, nor of great privation. At the end of the wet season, which he has spent at the central station, or down river, he, in company with other men, goes by canoe up a small stream to his camp, taking with him his supplies for the five months of tapping. He taps the trees in the morning and collects the milk and smokes it in the early afternoon. On his round he carries his rifle and gets enough game to give him a varied diet. He spends a month getting to camp and making ready for work, and another month in getting his rubber to the station. The five months of rain he spends at the central camp, or visiting down river, where he succeeds in spending a little more than his year’s profit. Every year finds him deeper in debt to his employer, but he remains happy and continues going the old rounds. He may go back to the same camp for ten seasons, but he seldom makes any clearing or does any planting. He prefers to buy all his provisions. The river may be full of fish, but he would rather buy canned sardines than go fishing. In the Acre Territory, more than two thousand miles up river, we ate American salmon, sardines, beans and potatoes.

Image Number: 17838

The Indians of the Purus collect very little rubber, and few are seen along the river. The rubber gatherer gets all the game in the woods and thus forces the Indians farther into the interior, away from the rivers. When the water is low, the Indians come out and camp along the sandbars, in order to fish. At the time of our visit there were none to be seen along the river. We made several journeys on foot back to their villages, fording numerous streams, with our packs on our heads, and wading through the mud and water of the lowlands. For the Indians, such travel is not so unpleasant, because the men wear no clothing, and the women only a short apron. Such tribes have very little for the collector, with the exception of bows and arrows, hammocks and a few cooking things. Yet their languages, customs and beliefs were interesting and well worth the difficulties in recording them. We visited four tribes, Catyana, Ipurina, Jamamadi and Nawisima, each of whom, we learned from our linguistic material, speaks a dialect of the Arawak language. We found here many customs which resemble those of other tribes of the same stock in British Guiana, two thousand miles away. The Jamamadis have a physical test for marriage for men which might be introduced into civilized society with profit to the race. The young man must first get consent from his parents, the girl and her parents, and the chief. Then, on the morning of the wedding, after he has had his bath in the river, he is taken by the chief to a heavy log. The prospective bridegroom must carry this log on his shoulders a fixed distance; if he is unable to do so he is not allowed to marry. In this way inherited weaknesses and physical defects are eliminated, and a strong vigorous race is the result.

An Ipurina marries his cousin on his mother’s side. The wedding takes place when the full moon is near a bright star. The moon, which is a woman, knows when the girl is old enough to marry. At death “the angel of the eyes” goes to the sky and never returns. They perforate the ears, nose and lips to prevent them from growing too large, but never wear any ornaments. They pull out their eye-brows so they can see more clearly. The rainbow is the reflection of the colors of a large animal that eats the rain. It can never rain as long as you see his colors.

Image Number: 17910

The Jamamadis marry outside of their own village, but not necessarily cousins, and the man goes to live in his wife’s village. The man who marries the oldest daughter of the chief becomes the next chief. He is usually the son of another chief. His hammock is hung between those of his two wives. Death ends all. Nobody knows where the river goes, nor where the sun goes at night. The women wear joints of bamboo an inch in diameter in the lower lip, the septum of the nose and in the ears.

Photography in the tropics is very difficult, on account of heat and moisture. One must carry plates and films in sealed tins, and develop them at night by the riverside, as soon as they have been exposed. We found it necessary at times to dry our plates by the fire. On this voyage we had difficulty in getting the proper exposures. The villages were among the tall spreading trees, without any clearing except that of the underbrush. It is very difficult to appreciate the density of the shadows in these places. As a result, our photographs were underexposed. On one occasion we took a dozen photographs, eleven of Indians, and one of a rubber collector. During my absence of a few minutes, the collector pulled out the slides of the plate holders looking for his picture and ruined all but a half of one of the plates. This was not learned until the plates were developed and the Indians had gone.

During our journeys we kept a record of temperature, but it is of little value, because we were not in any one place for an entire year. The record of the government engineer, Joao Alberto Masô, for 1911, gives a very good account of rainfall, temperature and humidity in the Acre Territory.

Average maximum temperature……………. 94 degrees

Average minimum temperature……………. 81 degrees

Average humidity………………………………. 88 percent

Total rainfall……………………………………….. 69 inches

Total rainfall for November, December,

January and February…………………………….. 42 inches

Total rainfall for May, June and July……………. 0 inches

The humidity of the four months of greatest rainfall is 90 and for the three dry months it is 85. The hottest days are in July, August and September, with an average for the three months of 95 degrees. The coolest days are in February, March, April and May, with an average of 89 degrees. (At Para the hottest day on record was 96 degrees.)

The time and the amount of rainfall varies greatly in the different regions. About the islands in the lower Amazon, just under the equator, the rainy season extends from January to June and the rainfall is said to be 10 feet a year. At Dada Nawa, British Guiana, in latitude 21⁄2 degrees north the fall is 60 inches and nearly all occurs in June, while at Boa Vista, sixty or seventy miles farther West in the same latitude, the rain falls at the same time of year but measures only 42 inches. The agricultural experiments undertaken by the government of Brazil at Boa Vista failed because the rainfall was not sufficiently distributed throughout the season for the development of crops. On the Brazilian side one eats only farinha and dried beef. On the British side Mr. Melville has introduced irrigation by means of American windmills and grows all kinds of tropical fruits and vegetables, such as oranges, bananas, cashews, mangoes, beans, potatoes, tomatoes, etc. The soil is fertile, there is plenty of underground water, there is a constant east wind—hence the windmill is all that is needed to make this a valuable agricultural region.

Image Number: 36713

When traveling in the upper rivers among the rubber gatherers by canoe, one receives information from the shore by signals. Every man carries a rifle and uses it for game and for communication. These signals are known and heeded by all. One shot means nothing more than shooting game. Two shots at an interval of ten seconds means good day—a simple salutation—or who are you? when hailing a passing canoe. As we were strangers, two shots required us to stop and to give a satisfactory account of ourselves before being allowed to proceed. Three shots at the same interval means that immediate help is wanted. Four shots is the signal to announce a death at the place. Five shots tells everybody that a festival is in progress and that he is invited. One Sunday when we were coming down the Amazon in a launch far from shore, a man came out in a canoe and fired five shots, whereupon we turned and followed him in to shore. There we found nearly a hundred people and spent the afternoon dancing and feasting with them. In this particular case we were invited because they expected us to add something to the supply of liquid refreshments. This the captain of the launch did most liberally. The stranger is often surprised at the consideration the captain shows for the upriver people. For the one who can read he has a newspaper, for the children he has candy or even an apple from Oregon, which he can buy any month in the year at Para for ten cents. Those who are fortunate enough to sit at the captain’s table soon understand it all. Choice fruits, vegetables, chickens and wild game find their way to his room at every stop. He always has a good supply of such things left over to take home to his family upon his return.

Long journeys up river on the launches become somewhat tiresome, yet there is always something to attract one’s attention. Numerous stops must be made to take on wood for fuel because coal is too expensive for river steamers. Cattle for the voyage must be taken from the lower Amazon and killed aboard as needed. Every day the boys must go out in canoes to cut grass to feed them. Occasionally one falls overboard and there is great excitement until it is caught. One day one reached the bank before it was overtaken and the boys spent several hours chasing it through the forest before they could catch it again.

Image Number: 17850

The launches which are subsidized by the government must carry a medical doctor and a postal clerk. If the clerk has a letter for a man the launch blows the whistle and the man comes alongside in his canoe but the launch does not stop. The same thing is true if there is cargo for the man : the whistle gives him the information, and the launch carries him along until the canoe is loaded, when he casts off and floats back home. If the man on shore wants medicine or to take passage he fires a signal and starts out in his canoe to meet the launch. On the return voyage more stops must be made to take on the rubber.

Image Number: 17852

One’s traveling companions are Brazilian officials, owners of rubber stations, rubber collectors; Turk, Assyrian and Jewish traders. In Peru, Spanish is the launch language and in Brazil it is Portuguese. One hears every language, from Arabic to Arawak, but no English. The day is largely spent at the table. Coffee at 6.00, breakfast at 10.30, coffee at 2.30, dinner at 5.30 and a coffee nightcap at 8.00.Wine is always served with the meals. We happened to be in the Acre at Easter time. Effigies of Judas were burned at many places along the river banks. Fast days were observed aboard the launch; that is, the gong did not sound to call us to our meals, but the regular meals were served for those who did not care to fast—there were not many vacant places. These launches under government contract are not allowed to do any trading. They carry a refrigerating plant but cannot sell ice. They sell beer and wine on board to passengers 2,000 miles up river at the same price as at Para. This is often one-fifth the local price for warm beer. It is little wonder then that many come aboard at every stop, for a cold drink. They have a saying among themselves that they sit on the river bank from one launch to the next.

It is interesting to note the parts the people of the different nationalities play in the business of the Amazon valley. In Peru the owners and the collectors of the rubber are Peruvians, but the trade is in the hands of English, French, German, Spanish and Moroccan Jews, while the shipping is wholly in the hands of the English who own the floating docks at Iquitos. In Brazil the owners and collectors are Brazilians and many of the launches trading up river belong to Brazilians. But the majority of the launches are owned by an English concern which is not allowed to trade and whose launches must be manned by Brazilians—pilots, captains, officers and men. This company also controls the docks at Manâos and Para and is associated with the company which controls the foreign shipping of the whole valley. Brazilian ships do a coasting trade as far as Manâos, and the ships of a Brazilian line from Rio to New York call at Para. The small business in the cities and towns is done by Turks and Assyrians, but the larger business of supplying the rubber men, the nut collectors and the cattle ranches is done by Portuguese houses. The exporting houses are German, English, and American, while the foreign banks are English.

W.C.F.

1 For method of manufacture and use, see Vol. VI, No. 2, of the MUSEUM JOURNAL.