Notwithstanding adverse conditions which could not fail to affect the fortunes of all public institutions in this country such as the University Museum, the constructive work of the Museum during the first half of the current year has not been diminished. At no corresponding period have more important accessions been made. At the same time, reports from the expeditions in the field have indicated satisfactory progress in their several fields of labor.

In the last number of the JOURNAL attention was called to the accessions of the first three months of the year. Among the objects described in detail was a Greek stela on the fourth century B.C., the importance of which is well known to everyone acquainted with ancient Greek sculpture.

Following the purchase of this monument of ancient Greek art, the Museum had occasion to be congratulated again upon the acquisition of a great Chinese sculpture of the Wei Dynasty which was acquired through the generosity of Mr. James B. Ford. This sculpture has on its front a statue of Maitreya, the future Buddha and Messiah for whom the Buddhist world is waiting, and on the reverse a long inscription in ancient Chinese characters. It has been set up in a central position in Harrison Hall directly opposite the entrance, where it has an appropriate setting as the most conspicuous object in the room and the most impressive monument of ancient Chinese art that has come into the possession of the Museum. The gold and colors with which the stone was overlaid still cling to the face and to the draperies of the statue, as well as to the canopy that rises above its head, imparting, by their softened glow, a warmth to the whole monument, that harmonizes well with its present surroundings.

The date, 516 A.D., which is found in the inscription on the reverse, is of peculiar importance, for it enables us to assign this great work beyond dispute to the Wei Dynasty and helps to establish a chronology for the early periods of Chinese sculpture and especially to identify the style and method of treatment that marked the movement that flourished under a powerful Buddhist impulse in the Northern Kingdom of Wei during the fifth and sixth centuries.

It is not possible to mention individually all of the objects that have been acquired during these months, but there is one in addition to those mentioned that claims ‘the distinction of special reference. The object referred to is a large rug of the K’ang Hsi Period (1662-1723 A.D.) which has lately been purchased and which is now on exhibition in Harrison Hall. It measures twenty-four feet square and is in a perfect state of preservation. Ancient Chinese rugs are rare and this fact, together with their great beauty of design and color, ought to make the acquisition of so perfect an example an occasion for renewed interest on the part of students and lovers of art generally in the opportunities which the Museum affords for advancing their knowledge and increasing their enjoyment. The accession of this remarkable rug calls attention also to another use of the Museum, which is to provide correct models for practical application in those industrial arts which are founded on the adaptation of artistic design to mechanical processes, such as the manufacture of rugs. In other words, by showing good models, the Museum can bring together the artist and the manufacturer in a combined effort to get rid of ugliness.

Image Number: 11820

Mr. C. W. Bishop, Assistant Curator of the Section of Oriental Art, whose departure for China was announced in the last number of the JOURNAL, arrived in Japan on the 31st of March. He writes from Nikko, under date of April 10th, as follows.

“The day following my last letter to you, dated March 7th, Professor Sayce left for Honolulu, after a final talk in which he suggested that we investigate together the work done in China by Japanese archaeologists, with a number of whom he is acquainted. The Japanese have done some very important work in that field, and it will be well for us to familiarize ourselves with their results. In no way, I am sure, could this be better done than through Professor Sayce’s help, for he stands as high with the Japanese, both officials and students, as he does elsewhere; I think you know that he was decorated by the late emperor, and he tells me that he has been granted the privilege of seeing the Shosoin at Nara this year. I consider it a piece of very great good fortune that the Museum’s actual field work in this region can be inaugurated so auspiciously.

I shall be leaving for China in about a fortnight. Much of the Japanese work along archæological lines has been done in Shantung province, and Professor Sayce has already put me in touch with one of the men who have done most there; he also suggested that I visit Tsing-tao on my way to Peking, which I can very easily do. So in all probability I shall go to Shanghai by boat, and see what can be done there in the way of additions to our library; then proceed by coasting steamer to Tsing-tao and thence to Peking, probably by rail.”

The expedition to the Far East under Mr. Bishop’s direction has been planned to continue for three years and while its general scope has been laid down on broad lines, the details of the work will be developed gradually by Mr. Bishop in the field. The principal purpose of the expedition is to pursue archaeologically and ethnological research. The history of Chinese art, especially in its earlier periods, is buried in the obscurity of the past, and, although it reveals itself in isolated and impressive outcrops, still awaits investigation, and the separate and fragmentary facts that have come to light remain to be coordinated. In these respects Mr. Bishop’s work, through the aid of Chinese scholars and written Chinese records, may be expected to help to bring home to us a better understanding of the Chinese people, both in antiquity and in their historic present.

The Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. Expedition to Egypt, after having completed a three months’ period of excavation at Dendereh, moved its camp to Memphis and resumed on that great site the excavation of the Palace of Merenptah, interrupted at the beginning of July, 1916, by the rising of the Nile. The plan upon which this expedition has worked during the last three years in Egypt has been to dig at Memphis during the season when the low Nile leaves that site dry, and to retire south to Dendereh, which is above high water, to dig there during the high Nile. Under this arrangement the first of March is about the time for beginning work at Memphis.

The expedition is made up of Mr. Fisher and his assistant, Mr. Sanborn, together with one hundred and sixty native workmen and foremen. Fortunately, conditions in Egypt have continued favorable for the work of the expedition. In one respect only was any change necessary during the present year. It was found that the price of food had advanced to such an extent that special provision had to be made for the workmen so that their earnings might be adjusted to their needs.

The following letter has been received from Mr. Fisher, written at Memphis on April 23d.

The results of the excavations made at Memphis and at Dendereh by the Egyptian Expedition have been extensive and important. Many objects of ancient art: sculpture, metal-work and pottery have been found. In addition to these, the architectural details of the great palace of Merenptah are being gradually uncovered at a depth of eighteen feet, laying bare the most important example of a royal palace that has ever been made known in Egypt. This palace is so large and so deeply buried that it will take some years to clear the entire plan, and this architectural feature of Mr. Fisher’s discoveries when complete will furnish for study rich material of a kind that will not be otherwise accessible. Many of the movable objects that have come to light in the excavations will eventually be displayed in the University Museum. For the present they are stored in Egypt for greater safety.

When the Egyptian Hall of the Museum shall have been built, the discoveries of the Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. Expedition to Egypt adequately installed will afford a very impressive view of the life of ancient Egypt. As a part of that exhibit it is planned to reconstruct in the Egyptian Hall several of the rooms in the Palace of Merenptah showing the wonderful inlaid doors and lotus columns. Such an exhibit would comport well with the educational purpose of the Museum and would be a telling tribute to the work of the expedition. In order to effect this purpose it will be necessary to build an extension of the Museum for the Egyptian Section, such extension to consist of at least one large hall and several smaller halls. In order to take advantage of the opportunities that have been afforded the Museum in Egypt, to give the work of the expedition its due, and to give the public all the advantages that have thus been gained, the building of the Egyptian Section will be an obligation and a necessity.

Not only have the Egyptian collections remained in Egypt, but collections assembled by Mr. Alexander Scott in India have, on account of the risk and high rate of freight and insurance, been stored in Bombay awaiting a favorable opportunity for shipment. Since the Museum has acquired so many fine examples of the Buddhist art of China, the collections which Mr. Scott has procured assume a more than usual importance for the Museum, because they will serve to illustrate the affinities that exist between the artistic expression of Buddhism in India on the one hand and in China on the other. As India was the mother of Buddhism and China the child, and as India derived artistic inspiration from the West, a comparison of early Buddhist art in China with that of India is full of interesting possibilities.

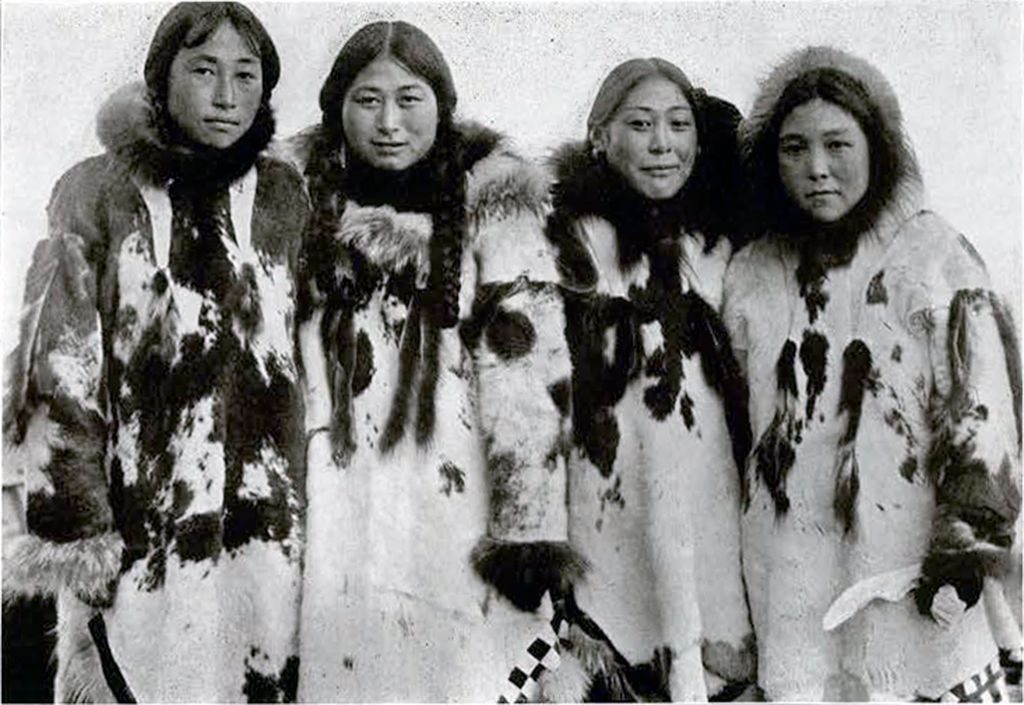

Alaska is a country which, till very recently, has been left in possession of the natives, who, in turn, retained their original customs and their original arts. At the present moment Alaska is undergoing a very rapid transformation through its exploitation along many lines of development. While this exploitation proceeds the native disappears, or at all events his customs and arts become obsolete. With this thought in mind the Museum, through Mr. John Wanamaker, has equipped two expeditions, one to work in the south and the other to work in the north of Alaska. By the generosity of Mr. Wanamaker, Mr. Louis Shotridge of the Museum staff, a full blood Indian of the Chilkat tribe, has been since the summer of 1915 working among his own people in southeastern Alaska. Mr. Shotridge’s work has been marked by great industry and aptitude. Among the collections received are old works of art which have been handed down for many generations in the Chilkat tribe and which will be among the most prized possessions of the American Section of the Museum. It is our purpose to make a sustained effort which will afford in the end a complete historical and ethnological study of the Tlingit people, to whom the Chilkats belong, and to assemble in the Museum, collections which will faithfully represent their manners and customs and especially the rich and remarkable art which was an expression of their inner life.

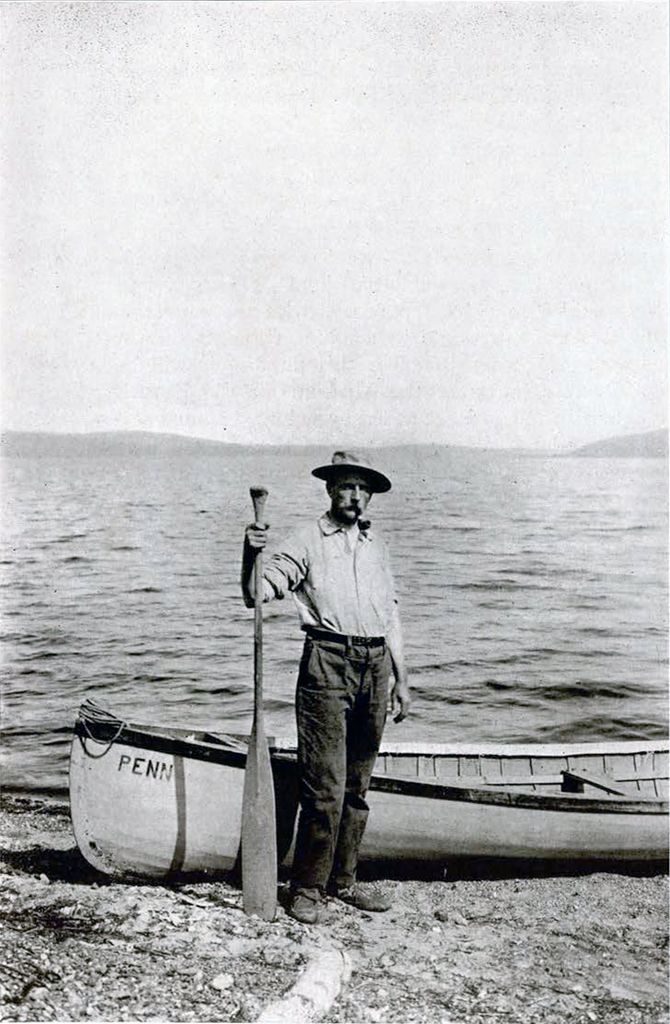

The expedition to northern Alaska left Seattle early in June in charge of Mr. W. B. Van Valin and will proceed to work among the Eskimo on the shores of the Arctic Ocean. Some of these Eskimo have seldom been visited and still retain all the characteristic institutions which have been handed down from unknown generations.

The Museum possesses already an extensive collection illustrating the life of the Eskimo in which can be seen a great inventiveness on the one hand and an active artistic temperament on the other. The expedition to Arctic Alaska will forge an important link in our knowledge of the chain of pure Eskimo culture that reaches from Labrador on the Atlantic side of the continent all the way across the shores of the Arctic Ocean and Bering Sea to the northern Pacific. Almost all of this far flung culture area is already represented by the Eskimo collections in the Museum.

The special exhibition, opened on the evening of April 11th, has given pleasure to the many visitors who have taken advantage of an unusual opportunity to profit by a very inspiring lesson in several departments of art. When this exhibition was opened, the new Chinese statue of Maitreya was shown for the first time and the invited guests had also an opportunity of seeing an exhibition of Greek sculpture such as Philadelphia has not hitherto enjoyed. The collections of Greek and Roman coins were also shown for the first time. These several features of the exhibition remain as permanent integral parts of the Museum’s collections. In addition were shown several loan collections which gave expression to the wish of the Museum to enlarge its interests, to strengthen its scientific and artistic uses and to amplify its educational work. These loans supplied for the time being, objects of the very highest importance of a kind that the Museum has not yet been able to acquire.

The collection of ancient Chinese jades was in itself an epitome of old tradition embodied in beautiful and curious carving and in the hardest material known to lapidaries; for jade was the medium chosen by the Chinese in ancient times to express in the subtlest terms of symbolism the thoughts and aspirations of mankind.

The vases of pottery known as Chun Yao, made by the Chinese potters of the great Sung Dynasty, must be regarded as unique examples of this exquisite and very appealing product of an age gone by, and of a technical knowledge that stimulates our imagination, though it baffles our skill.

To many people the supreme interest in the exhibition attached to the European tapestries. Among these were two that possess such exquisite beauty and such rarity that they invite special mention. These gems of the collection were two millefleur tapestries made at Arras in the fifteenth century. They belong to a class of tapestries of which very few are left and which in design, color and texture are quite beyond the resources of modern art and modern methods of manufacture.

Together with its constructive work along the lines which have been described, the Museum has issued during the first half of the year, five volumes in its regular scientific series. Four of these were issued from the Babylonian Section and one from the Mediterranean Section and all represent original work done in the Museum by its own scholars or by scholars working under their supervision and with the facilities for investigation and instruction which the Museum affords.