It is becoming steadily more evident as archæological study progresses that advancement in the arts of civilized life is as a rule the offspring of the energy liberated by the impact of one culture upon another. We know now that at least two peoples had a part in the dim prehistoric beginnings of ancient Egypt. The respective shares of Semites and Sumerians in the founding of the civilization of Babylonia are becoming more apparent as time goes on. The wonderful Cretan culture of Minoan days had to go down under the blows of Achaean and Dorian invaders from the unknown north before classical civilization could arise.

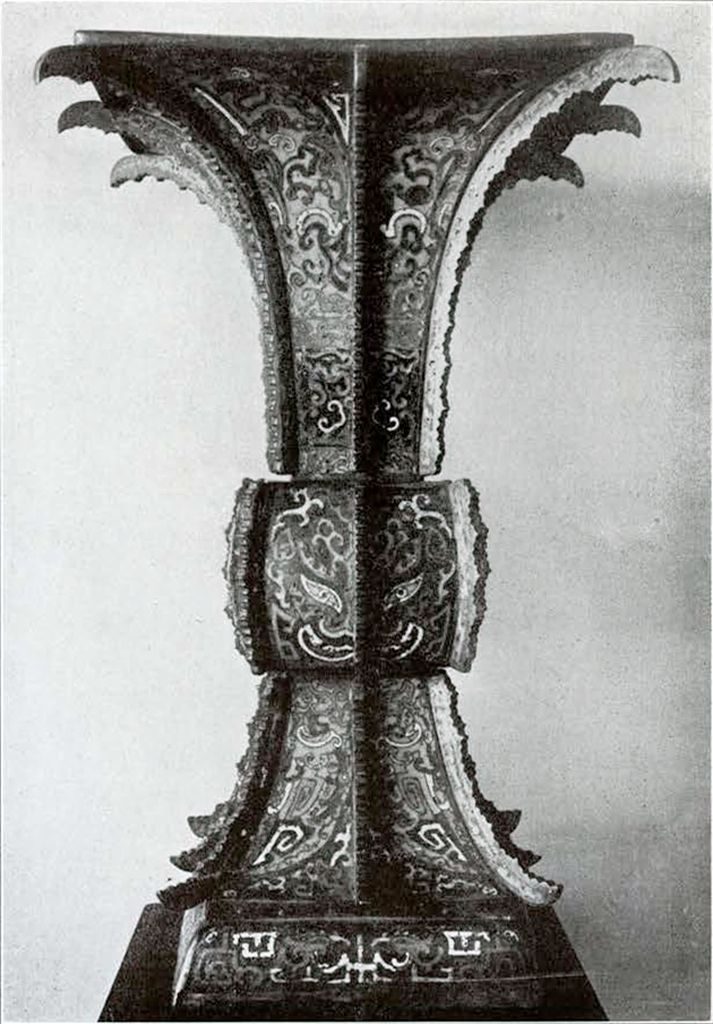

Museum Object Number: C63

Image Number: 1718

This same phenomenon may be traced over and over again in the history of China, and only by recognizing it and allowing for its effects can we hope to reach a clear understanding. It appears pretty certain that at one time the ancestors of the present Chinese were savages, leading a life comparable to that of some of the ruder hunting tribes found upon this continent by the early French explorers and missionaries. According to their own traditions, which here have the ring of genuineness about them, they were a race of hunters, clad in skins and sheltering themselves in caves and rude brush windbreaks; tracing their descent through their mothers alone, and ignorant of the art of writing, of the use of domestic animals, and of agriculture.

At length, the legend goes on to tell us, there arose a succession of what we call nowadays culture heroes, headed by a personage named Fu-hsi, who taught the people the proper regulation of marriage, the arts of writing and of divination (originally closely connected), the rearing of animals, and the principles of agriculture. It can scarcely have been a coincidence merely that Fu-hsi is said to have been born in the Wei River valley, in that very region in in the extreme northwest of China through which, from the beginnings of history, ideas and objects and peoples have been traveling to and fro between the Middle Kingdom and the lands to the far west.

This process, of whose effects during the prehistoric period we as yet possess only legendary and inferential evidence, has continued, intermittently, down to the present day. Its effects upon the particular clan or tribe which happened for the time being to occupy this eastern terminus of the great trans-Asiatic trade route have been most marked. Time after time has it occurred that such a clan, undoubtedly strengthened and invigorated by the constant succession of culture stimuli which it was receiving from other nations, far to the west and doubtless wholly unknown to it even by name, made themselves the masters of the whole of China, while the capital of that empire has been located in this region, along the banks of the Wei, more often and for a greater number of years, than in any other region.

Among the many contributions from the west which reached China through this channel was the Buddhist faith, which was introduced about A.D. 67, under the patronage of one of the emperors of the Later Han dynasty. Its early career in its new home, however, was on a most modest scale. In fact it seems practically to have vegetated for a period of something like two centuries. No Buddhist statuary has come down to us from this early epoch, and the explanation probably is that there was nothing of the sort worth mentioning then in existence. It was not until the Mahayana, or “Greater Vehicle,” of Buddhism developed in India during the first century or two of our era into a highly complex and esoteric system of polytheism, that a school of religious sculpture arose, in the shape of the most interesting Gandhara statuary, of mingled Greco-Indian inspiration.

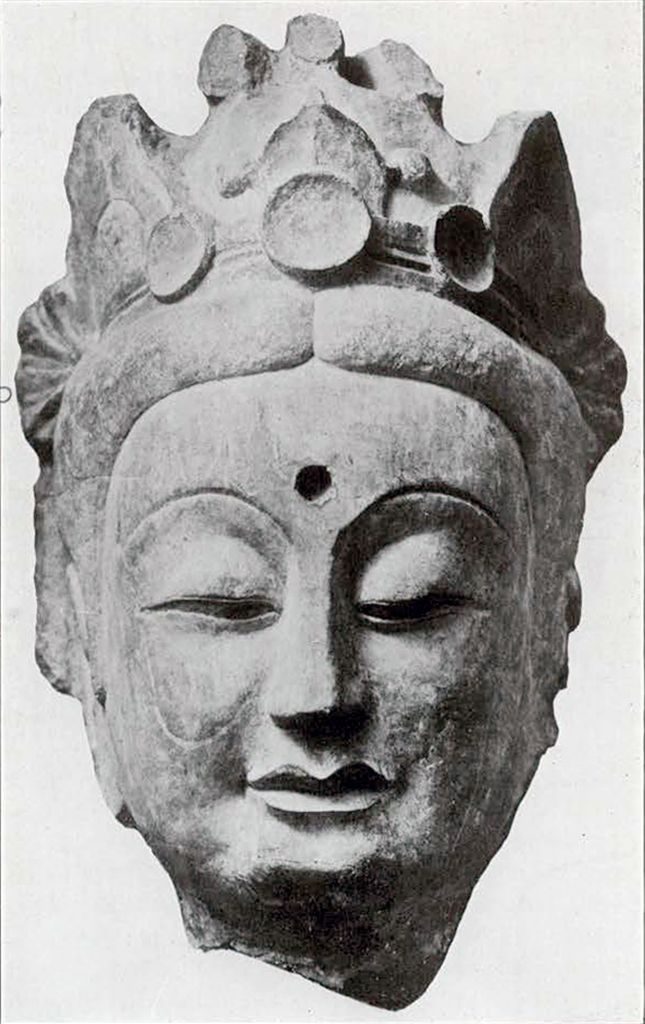

Museum Object Number: C353

Image Number: 1321

Just at the time when this was taking place in northwestern India, however, the great Han dynasty, which for some generations had maintained a fairly regular intercourse with the civilized regions of western Asia, fell a prey to internal dissension and rebellion. The result was that one of the numerous partitions of China took place, and for a century or two communication with the west was almost wholly suspended. Hence it is that we are unable to trace anything like an evolution of Buddhist sculpture on Chinese soil, but find it appear, full blown, during the fifth and sixth centuries of our era, as an importation from the Buddhist kingdoms then occupying Turkestan and northwestern India. This importation was due to the activities of the Tartar kingdom known as the North Wei. This power, which does not appear in the lists of dynasties regarded by the Chinese as legitimate, established itself in the year 386, and in time came to occupy much of the northern part of what we call China Proper, while its influence also extended far into Manchuria, Mongolia, and Turkestan. Its rulers seem, many of them, to have been singularly enlightened, and they systematically tried to assimilate themselves as completely as possible to their Chinese subjects. Their Tartar followers were required to learn the Chinese language and to adopt the Chinese costume and customs, and at the same time the spread of the Buddhist faith was actively encouraged. At first the seat of their court was in northern Shan-si, not far south of the Great Wall. Here the country is flat and treeless, and seamed here and there with ranges of brown, barren, rocky hills through which torrents have in many places excavated gorges debauching on the lower land in great cones and fans of detritus.

It was such a gorge as this, about a day’s journey west of the capital of the North Wei (near the modern Ta-t’ung Fu), at a place called Yün-Kang, that the Buddhist devotees of the fifth century of our era selected as a fitting site for a group of rock-cut temples which even now, in their present ruinous and uncared-for condition, are among the most remarkable and most noteworthy sculptural remains to be found anywhere in the world.

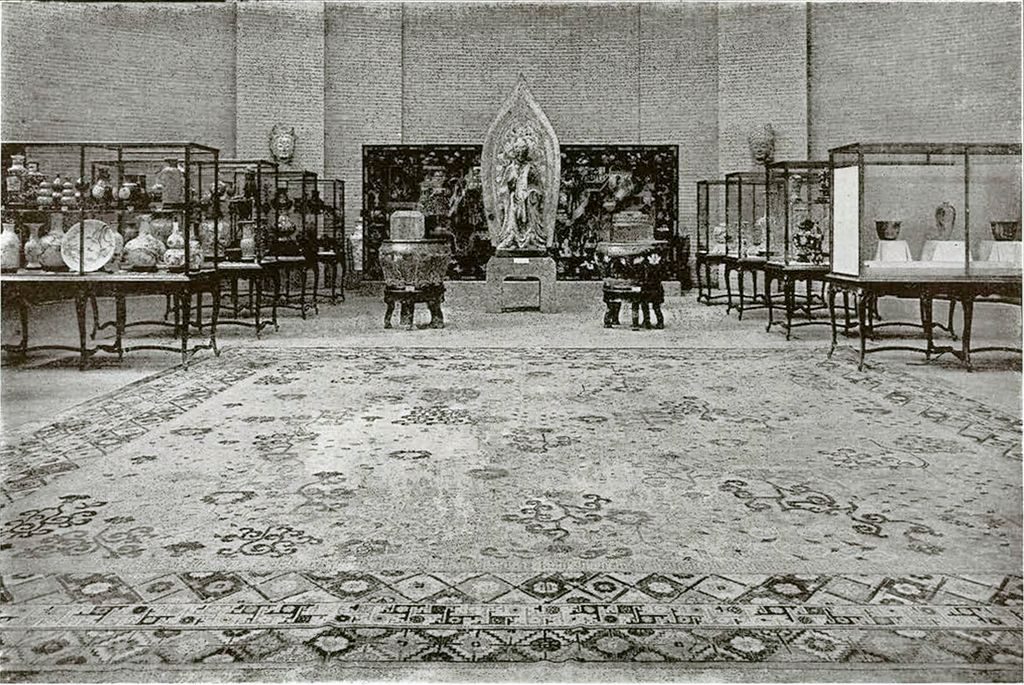

Museum Object Number: C354

Image Number: 1322

At the point where these ruins occur the gorge widens out to perhaps half a mile in breadth. To the south it is bordered by low barren hills crowned here and there with watchtowers to guard against marauding Tartars and robber bands. The northern side, however, rises in steep cliffs from one to two hundred feet in height, and it is here that we find the temples. For hundreds of yards the face of the rock is simply honeycombed with excavations, great and small. The majority of course are very small; mere shrines containing statues of quite diminutive size, though often of the highest artistic merit. The principle temples, however, are truly works of the most remarkable character. The face of the cliff has been smoothed away for a distance of several hundred feet in order to form the exterior wall of the temples, which are themselves carved out of the heart of the living rock. Around and above the entrances, which are elaborately carved with various Buddhist figures and decorative motives, appear deep mortises and sockets which formerly held the ends of the timberwork of the temples that once rose three and four stories high against the cliff. These temples, built almost wholly of wood as they were, have long since disappeared. The two easternmost of the great grottoes, however, have had erected before them in recent times edifices which doubtless follow fairly closely the lines of the original buildings, save that they have the upturned corners of the roofs which we have come to look upon as characteristic of Chinese architecture, but which were as yet quite unknown in the era of the Northern Wei. Much erudition has been brought to bear to show that these peculiar curving roofs are a reminiscence of the time when the ancestors of the Chinese were a nation of tent dwellers. Unfortunately for the theorists, however, the ancient Chinese monuments show that the original Chinese roof had no such feature as an upturned corner, the line of the eaves being absolutely straight. As a matter of fact, the type of roof which we have come to regard as typically Chinese made its appearance in China only about the sixth or seventh century, and seems to have been due to the influence of the type of Himalayan Buddhism which was then making such headway in the Celestial Kingdom. It soon spread to Korea and was carried thence to Japan, where it appears in an early form in buildings which, though erected twelve hundred years ago, of no more durable material than wood, are still standing.

The ancient structures at Yün-kang were not so fortunate, for they perished long ago, leaving exposed to the open air the inner gateways, cut through the face of the cliff, which give into the temple proper lying beyond, in the heart of the rock. Upon passing through one of these gateways one finds himself first in an antechamber, rising many feet upward, illuminated by such light as comes in through the door and through other openings cut through the cliff higher up, and decorated with an infinity of exquisitely chiseled figures of Bodhisattvas, Deva kings, and other personages, together with symbolical animals, birds, garlands, and a multiplicity of decorative designs. In the further face of the antechamber, usually in line with the outer door, is another entrance, also highly ornamented, and here, sometimes, as a result of greater protection from the elements, one finds well preserved evidences of the rich coloring so lavishly used by these old world artists. Passing through this inner door one finds himself in the adytum itself, the very Holy of Holies, a tremendous chamber, its walls and roof lost in the seemingly limitless gloom overhead, whence the voices and footfalls of intruders come reverberating back multiplied manifold in volume.

It was the common practice of the excavators of these stupendous grottoes to leave the rock in the central portion of the chamber as a support for the roof, and this gigantic column was itself carved and decorated in a variety of ways, all most wonderfully effective and pleasing. Sometimes it was shaped into the likeness of a colossal Buddha sitting crosslegged upon a lotus flower, lost in profound meditation. Sometimes the central pillar, instead of representing a single Buddha, was carved into four figures, back to back, in various significant attitudes, full of a rich symbolism. Again, this huge pillar of stone may be chiseled into the semblance of a Buddhist pagoda, carved in utmost detail of column and cornice and entablature, with friezes of extraordinary vividness, while in the balconies on all four sides stand great statues of Bodhisattvas, with Deva kings in attendance and angelic musicians hovering about in the background.

But not all the sculpturing is reserved for the great central columns. The walls, and the lofty ceilings as well, are carved with the same conscientious care as are the more readily visible portions of the grottoes. I carried with me on two visits to Yün-kang a powerful electric torch which illuminated the ceilings quite effectually, and the most careful examination failed to show the slightest evidence of “stamping” on the work in these locations, although it is difficult to conceive of any system of lighting in the old days which could have done much in the way of illuminating these remote and lofty portions of the grottoes.

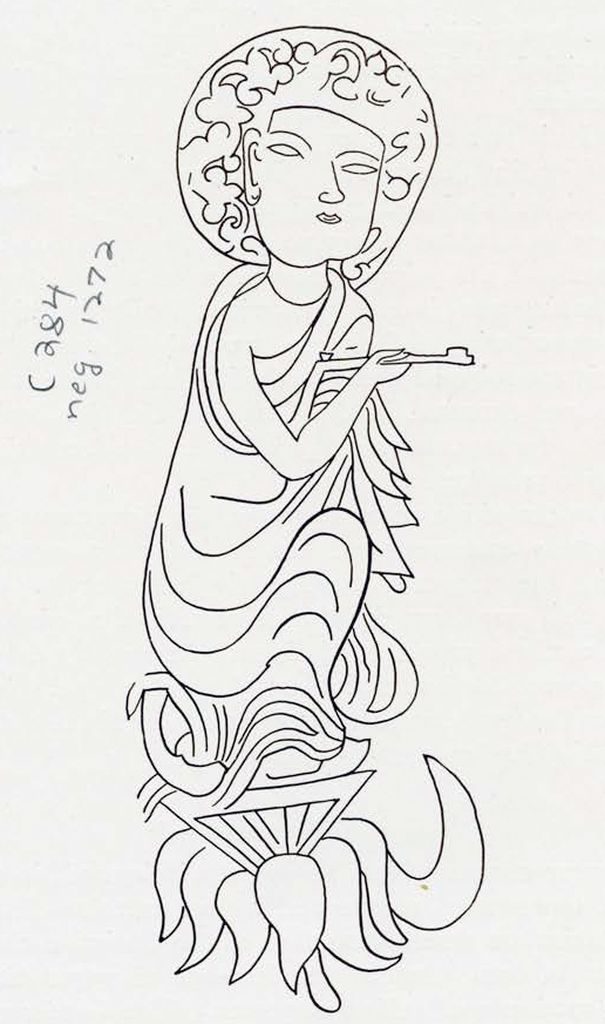

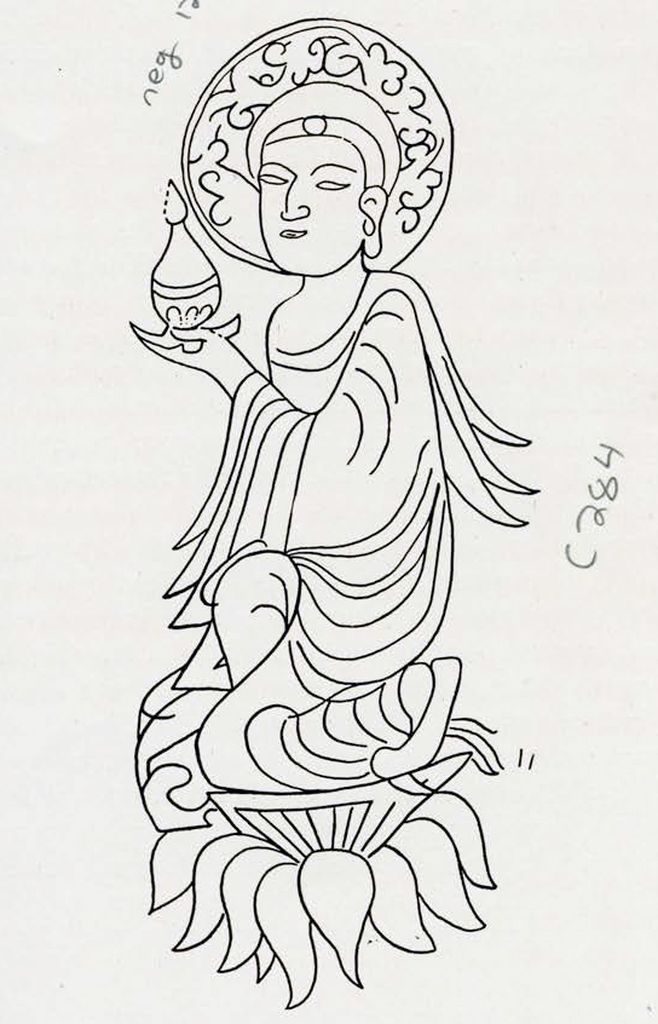

Museum Object Number: C284

Image Number: 1272

The character of the carvings on the walls and ceilings is of the same general character as that upon the central pillars and in the antechambers, but is even more varied and covers a larger number of subjects. Reliefs portray well known scenes from the life of the Buddha, worked out with the most minute attention to costume and ornament and feature. Again, there are the more conventional groups showing a seated Buddha flanked by two smaller Bodhisattva figures, standing. Or whole sections of wall, covering hundreds of square feet, may be chiseled into panels of regular size, each containing in relief a representation of a sacred personage; in some instances these panels are scarcely more than an inch or an inch and a half high, and yet each one is worked out in most painstaking detail and exactly repeated many hundreds of times.

As has already been intimated, the artists, in the telling of the sacred stories in stone, trusted not to form alone but to color as well. The principal figures were gilt, and much of the gilding still remains, tarnished by age and the smoke of incense and doubtless in some cases renewed from time to time. The subordinate figures and the decorative motives were colored in the most tasteful way imaginable. The total effect is one of the utmost richness; but it is a subdued richness, harmonizing admirably with the still solemnity and gloom of the vast interiors and the awesome calm of the barely visible central figures towering high up into the darkness.

It is impossible for us to imagine what these now deserted and ruinous sanctuaries must have been in the days of their prime, when they were the favored resort of princes and people, when a short day’s journey away stood the capital of one of the great world empires of the time, and when the mild and peaceful teachings of the Buddha formed the rule of life for so much of southern and eastern Asia that has since turned to Hinduism and the fierce creed of Mahomet. It may, perhaps, help us, however, to turn to the narrative of the monk Fa-hien, who journeyed across Central Asia to India in search of copies of the Buddhist scriptures during the early years of the fifth century, and whose own story of what he saw reveals so vividly, if unconsciously, his own courage and devotion and intense spirituality.

When Fa-hien came to Khotan, for example, he tells us that he found it a flourishing and prosperous kingdom, ruled over by a king and queen who were devout followers of the Law, and well provided with monasteries occupied by “several myriads” of monks. It is difficult for us now to realize that the peoples of Turkestan, rabidly fanatical and ignorant Mahometans as they have so long been, should ever have owed allegiance to the mild, tolerant, and peace loving faith preached by the followers of the Buddha. That this difficulty has not been ours alone is shown by the fact that the foremost Chinese scholars of the last dynasty, that of the Manchus, stigmatized Fa-hien as a liar, because he speaks of these Central Asian countries as being Buddhist, when, said the Chinese scholars, “all the world knows that they are Mahometans.” Unfortunately for the reputation of these Chinese savants, however, Fa-hien set out on his travels almost two hundred years before Mahomet was born, and the entire sincerity of his narrative has been most abundantly established.

Museum Object Number: C284

Image Number: 1271

During his stay at Khotan Fa-hien witnessed a great Buddhist festival which must have resembled closely the sort of thing that was going on in China at that time, under the rule of the North Wei. Doubtless the now silent and almost deserted temples at Yün-kang saw many a similar ceremony during those years, so that it may be of interest to transcribe a portion of Fa-hien’s account.

He says:

“At a distance of three or four li [a mile or more] from the city, they made a four-wheeled image car, more than thirty cubits high, which looked like the great hall of a monastery moving along. It was grandly ornamented with the Seven Precious Substances,1 with silken streamers and canopies hanging all around. The chief image stood in the middle of the car, with two Bodhisattvas in attendance on it, while Devas were made to follow in waiting, all brilliantly carved in gold and silver, and hanging in the air. When the car was a hundred paces from the gate, the king put off his crown of state, changed his dress for a fresh suit, and with bare feet, carrying in his hands flowers and incense, and with two rows of attending followers, went out at the gate to meet the image; and with his head and face bowed to the ground he did homage at its feet, and then scattered the flowers and burnt the incense. When the image was entering the gate, the queen and the brilliantly arrayed ladies with her in the gallery above scattered far and wide all kinds of flowers, which floated about and fell promiscuously to the ground.”

Toward the end of the fifth century of our era the reigning emperor of the North Wei moved his capital from northern Shansi southward to a point in Ho-nan province, in the region where the capitals of the half legendary Shang dynasty, of the later Chou kings, and of the rulers of the Latter Han had stood. Here, in a gorge called Lung-men, not unlike that at Yün-kang but narrower and more rugged, another series of rock-cut temples was commenced. The workmanship here is in its best examples scarcely inferior to that displayed at Yün-kang, and the general impression is much the same. There are the same deep grottoes, the colossal statues, the figures of Deva kings and Bodhisattvas and angels, the same decorative motives of garlands and wreathes and lotus blossoms. In general, however, the workmanship seems slightly inferior. It extends, too, over a longer period; for while the grottoes at Yün-kang are the work of a single half-century, the work at Lung-men was carried on not merely during the scant forty years of political existence that remained to the Northern Wei after the removal of the capital to Lo-yang; but some of it was accomplished under the great Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907) and even later.

The inspiration for the undertaking of these wonderful works in stone was a frightful persecution of the Buddhists which took place about the middle of the fifth century, and which wiped out practically every vestige of earlier temples and statues. Hitherto the temples had been built of wood, while the images were of bronze, earthenware, or sandalwood—all of them materials which readily succumbed to the onslaughts of the persecutors. After a few years, however, with the accession of an emperor favorable to the Buddhists, a reaction took place almost as extreme as the persecution which it followed. The followers of the Sacred Law, taught by experience, resolved to make their temples and their statues out of a material more durable than heretofore, and the rock-cut grottoes of Yün-kang were the result. No doubt the idea came from India and was inspired by the rock temples of Ajanta and elsewhere; but in its development the artists of the North Wei followed decidedly original lines. In the attitudes and attributes of their statues, it is true, they adhered to canons fixed long before, in northwestern India and during the long progress of Buddhism across Central Asia. Nevertheless the result was the founding of a school of religious art unlike anything the world had seen before. The artists of the North Wei succeeded in combining in their statues a grace, a restraint, and a simplicity fraught with the deepest religious feeling. In so doing they created a type of the divine in art which later centuries in China and Japan have often seen imitated but never yet equaled

Two Colossal Heads.

It has been only within the last few years that collectors in America have awakened to the importance of this old Chinese religious art. Nevertheless a number of important examples have already been brought to this country and have been acquired by various art museums and private collectors. Among the objects of this class which have come of late to the University Museum are two colossal stone heads of the best type, taken from figures of Bodhisattvas, possibly representing Avalokita, and also two figures of Maitreya, “the Buddha who is to come,” the one a large stone stela, the other a copper gilt statuette.

The two colossal heads, being fragments only, of course bear no dates; but it is fairly safe to assume that they belong either to the latter part of the North Wei period or to the earlier part of the T’ang. They are said to have come from the province of Ho-nan; but as that province has an area of nearly sixty-eight thousand square miles, that ascription can scarcely be called very definite.

Museum Object Number: C284

In spite of the paucity of our knowledge regarding the two heads under discussion, it is probably safe to say that their ascription to the province of Ho-nan is correct, and that further they came in all probability from the vicinity of the old North Wei capital at Lo-yang (the modern Ho-nan Fu). In my opinion they did not come from the famous gorge of Lung-men with its multitudinous grotto temples and its countless statues, great and small. It is more probable that they came from a point further down the Lo River, nearer its junction with the Huang Ho, where there are also large statues of early date and fine workmanship. In the total absence of any data it would be more than hazardous to attempt to fix any date for these heads; but it is evident that they belong to the very best period of Chinese Buddhist art, and were probably executed sometime during the sixth century of our era. At least they are quite typical Bodhisattva heads of that time in style, treatment, and technique. The one has a three peaked crown with a fillet about the base of the ushnisha or protuberance of the crown of the head, originally merely a knot of hair, a sort of chignon, but mistaken later for an actual formation of the skull, which came to be regarded as a mark of particular sanctity. The urna or jewel in the forehead is marked by a hemispherical depression, no doubt the socket which once held a crystal sphere or something of the sort. This urna was in all likelihood in origin a caste or tribal mark, mistaken later for a miraculous beam of light, also an attribute of special sanctity. The hair is parted in the middle and drawn smoothly back on either side. Traces of the pigment which no doubt once covered the statue remain on the crown and elsewhere. The companion head is very nearly the same in most particulars, but has a more elaborate crown with graceful floral designs, while the hair is arranged in a number of plaits or folds.

Of the merits of these two heads it is impossible to speak too highly. Of the numerous heads of Buddhistic statues which have been imported from China during the past few years these two are undoubtedly among the most beautiful. Faultless in outline and flawless in execution, they express in supreme measure that ideal of calm serenity, of spirituality, and of boundless mercy and love, of which Avalokita is the embodiment. There are few more beautiful concepts in any religion than that of the emanation of Avalokita, the embodiment of Infinite Mercy, from Amitabha, the Buddha of Boundless Light. The thought of course is that infinite knowledge produces infinite love. It is the exact complement of the Socratic idea that evil conduct is the consequence of ignorance. The sacred art of no country has been so successful as that of the Chinese of the sixth century of our era in expressing in stone those qualities of graciousness and majesty and loving kindness which are the attributes of the highest spiritual powers, and even in Chinese art the exquisite spiritual beauty and the mysticism and the ineffable calm of these two wonderful heads have rarely if ever been equaled.

Such heads as these under discussion are usually called heads of Kuan-yin, known to most foreigners as the “Goddess of Mercy.” This concept, however, is one which has come into being only within the past few centuries, long after the great epoch of the Northern Wei had come to a close. It appears to have resulted in the following way. In the times when the ancestors of the present Chinese people were gradually pushing out to the east and south from their ancient seats on the Yellow River, they came upon tribes of a culture totally different from their own who inhabited the coast lands and subsisted largely on the products of the sea. These maritime peoples naturally had a religion of their own, which, to judge from the very faint traces of it which have come down to us, seems to have been largely animistic, with some fairly well developed anthropomorphic deities; it perhaps resembled the religion of the primitive Japanese of pre-Buddhistic days, and may indeed have been actually connected therewith. At all events these seacoast peoples continued to worship their own gods and goddesses after their conquest and partial assimilation by the Chinese. One of these goddesses (a concept totally alien to anything in the original Chinese cosmogony) had her principal seat in the lovely Chu-san Archipelago, just south of the embouchure of the Yangtse River. This goddess, the special protectress of sailors, became the object of a cult of more than local importance. Consequently the Buddhists declared some centuries ago, with their customary astuteness, that the goddess was an avatar of their own Avalokita. The fact that the latter had always possessed masculine attributes, even to the extent of being represented with a moustache, presented no difficulty whatever; for Buddhist deities are pure spirit and therefore without sex; consequently they may be reborn in different incarnations either as male or as female. It is this theory of avatars that has enabled Buddhism to spread so readily among people in the animistic or polytheistic stages of religious belief ; for it was the easiest thing in the world to call the old gods and goddesses avatars of this or that member of the Buddhistic pantheon and let their worship go on with a minimum of friction or change. It was exactly the same process so cleverly and so successfully employed in pagan Europe by the early Christian missionaries, when they turned the pagan Saturnalia and Yuletide into Christmas, or the spring festival of the goddess Eostre into our present Easter; or when they rechristened the objects of many local cults by the names of various saints, after which the worship was allowed to continue without offence. It is a process to which all religions are subject. Not even the apparently uncompromisingly iconoclastic faith of Mahomet has been able to escape it, for many a tomb of an alleged Moslem saint is nothing but the present day successor of the shrine of some local god or goddess of far off pagan days.

Maitreya in Stone and in Bronze.

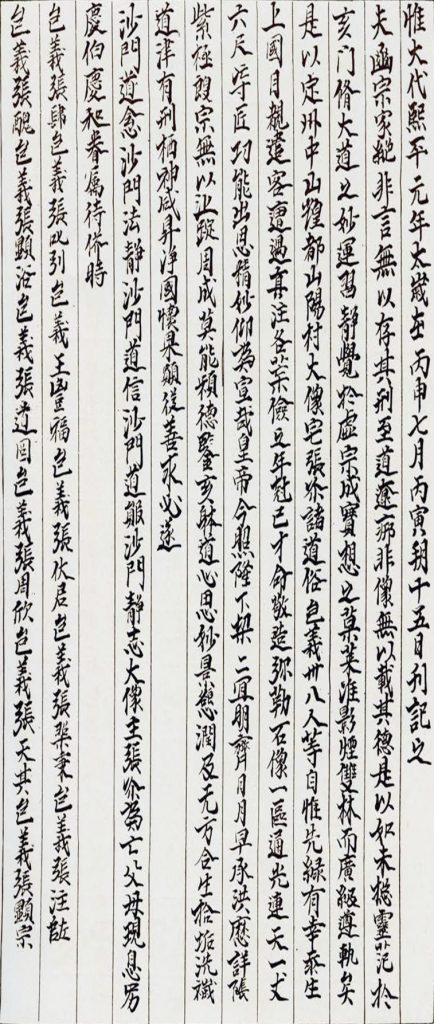

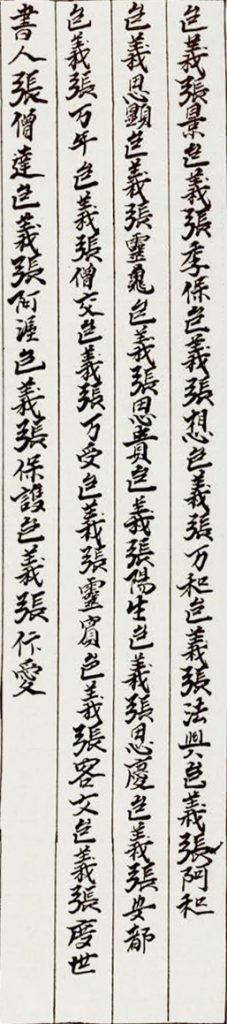

Of no less interest from an artistic standpoint than these two remarkable stone heads, and of even greater consequence from the archeological point of view are the two statues of Maitreya mentioned heretofore among the recent acquisitions of the University Museum. The reason why these statues are of such surpassing importance archæologically is that they both bear inscriptions stating the time and place of their execution. It will readily be seen how much this means in the way of aiding to fix the sequence and the provenience of the various types of Buddhist art in China, about which we as yet know so little.

Maitreya, like Amitabha and Avalokita, was a wholly metaphysical concept of the Mahayana or so-called “Northern School” of Buddhism, with its pantheon largely peopled with personifications of various ethical principles and abstract ideas. We are told that the historical Buddha, Sakyamuni, ascending to the Tushita heaven, there visited Maitreya and appointed him his successor, to appear as a Buddha on earth after the lapse of five thousand years. It is for this reason that he is sometimes called the “Buddhist Messiah.”

These two statues of Maitreya, the one in stone, of life size, the other of bronze or copper gilt and 24 inches in height, both date from the first half of the sixth century, and both were made in what is now the province of Chihli, the one in which stands Peking. They are strikingly similar in style and execution, and evidently form examples of a well defined type form. Hence the great importance of the fact that we are enabled to fix their date and provenience so exactly.

Museum Object Number: C284

The pure Gandhara school of Buddhist art, of Greco-Indian origin, penetrated unchanged toward the east only as far as Khotan; from that point onward influences which we can only call Turkic begin to manifest themselves, and it is this modification of the original Greco-Indian art in the regions which it traversed that produced, as a final culmination, the wonderful statuary of the Northern Wei. Once in China, a third influence began to make itself felt. Statuary of a sort had existed in that country from time immemorial; that we know from the written records, although no examples have come down to us; the earliest specimen of Chinese sculpture known to me is a figure of a horse from the tomb of a general of the Former Han dynasty, in Shensi, dating from B. C. 117. A few other examples from the centuries immediately following are known, either because they have actually come down to us, or, more often, because they are mentioned in various records. Consequently we know that Buddhist art did not find the Chinese field entirely empty of everything in the way of sculpture. Naturally this native influence manifested itself to a certain degree in the development of the various types of Buddhist statues, and while these were and remained fundamentally Greco-Indian, yet certain ones show a decided modification in the direction of the native pre-Buddhist types. In this class may be numbered these two statues of Maitreya, for in many details of costuming and ornamentation and general treatment they seem to hark back to the native styles rather than to those of Central Asia and northwestern India.

For example, costume in the India of pre-Mohammedan days was not developed very elaborately, for the simple reason that the climate did not require it. The wonderful Indian carvings at Borobodur, in Java, represent the people of both sexes as going about almost in a state of nudity. On the other hand, bodily decoration was carried to a very high pitch, because it was free to develop independently of dress, to which it bears such a close relationship in most lands. Consequently chaplets and wreaths and garlands and coronals and gorgets and necklaces and scarves and rings and bracelets and armlets and anklets were worn in the greatest profusion. The effect must have been something like that presented by the population of some of the Polynesian islands, where clothing was reduced to a minimum, but where the use of gay flowers and strings of brightly colored seeds and shells and other ornaments was most profuse.

Museum Object Number: C355

Naturally it was the upper classes that most indulged in this profusion of bodily decoration. Consequently when the various personages of the Buddhist pantheon began to be represented in art they were as a matter of course given the costumes, if they can be called such, of the princes and princesses of the day. Soon a symbolic meaning was given to the various details, in order to render easier the remembering of the sacred truths by the unlettered multitudes. This stereotyped them forthwith, and hence it is that we find the statues executed in the China of the Northern Wei still reproducing the costumes, or, perhaps better, the decorative schemes of their Indian prototypes.

In a number of instances, however, the personages represented are more amply costumed and less profusely ornamented than is the case with the statues of more purely Indian style. They seem better adapted, somehow, for the exigencies of a climate such as that of the northern provinces of China. Apparently they represent a nearer approach to that native art of which we get a faint adumbration from the few remains as yet known to us of the earlier period, when Buddhism had not yet made itself felt.

The Stone Maitreya.

Museum Object Number: C355

Image Number: 1152

The larger statue, which, as already intimated, is of life size, is as usual represented surrounded by an aureole. This symbol, which Buddhist art shares with that of the Christian church, is an exceedingly old one. Among the Romans of pagan times it was usually an attribute of deified emperors. The Greeks represented it in connection with their gods of light. Among the ancient Persians, from whom the people of India seem to have borrowed the idea, as they did pretty much everything else connected with the higher manifestations of civilization, it was the special attribute of the reigning sovereign. He, it was thought, ruled by the divine grace of Ormuzd, whose favor was made manifest by the sending of an aureole of celestial fire, the god-given royal glory which beamed only upon those of the right kingly line. It was this concept, developed and modified to suit the needs of Buddhism, that gave rise to the aureole which we find represented in this statue of Maitreya. As usual, the aureole is edged with flame, while its inner portions display flowers with green leaves and white blossoms, and just back of the head is shown a halo or nimbus. The figure itself, shown standing erect, is in full relief, the head in fact being carved in the round, although attached to the aureole by a support. There is a very high ushnisha, or protuberance of the crown of the head, one of the marks of a Buddha, and the ears had the usual long lobes, now long since broken off. There is no urna or mark on the forehead, but there are two whorls in the hair arrangement which may perhaps take its place; the hair itself seems at one time to have been painted a deep blue-green. The heavy gilding on face, throat, and breast go back to a very early date and may quite possibly be coeval with the statue itself. The pupils of the eyes are black, and the lips seem to have been colored red. The position of the hands is of course full of significance; in both the palms are turned to the front, but in the right the fingers point upward, while in the left the converse is the case. These positions, or mudras, are what are known respectively as the “preaching” and the “free gift,” and denote two of the functions of the personage represented. The fingertips in both hands are knocked off. There is a dark undergarment fastened by a girdle knotted in front with its ends hanging down, and a red outer garment with dark border—a very un-Indian costume. In the purely Indian Buddhistic statues the sole garment properly so called is a scarf worn over the left shoulder, leaving the right quite bare. The treatment of the drapery in this statue, arranged in many flattened folds or pleats and flaring out to either side, is characteristic of the earlier periods of Buddhist sculpture. The painting is much faded and worn, and can hardly have been done over for the last time later than the Ming dynasty (A.D. 1368-1644).

On either side of the statue, low down and near the edge of the aureole, is incised in outline a representation of an attendant Bodhisattva figure, the one with a basket of flowers and a censer, the other bearing a sacred vase and a “brush of power.”

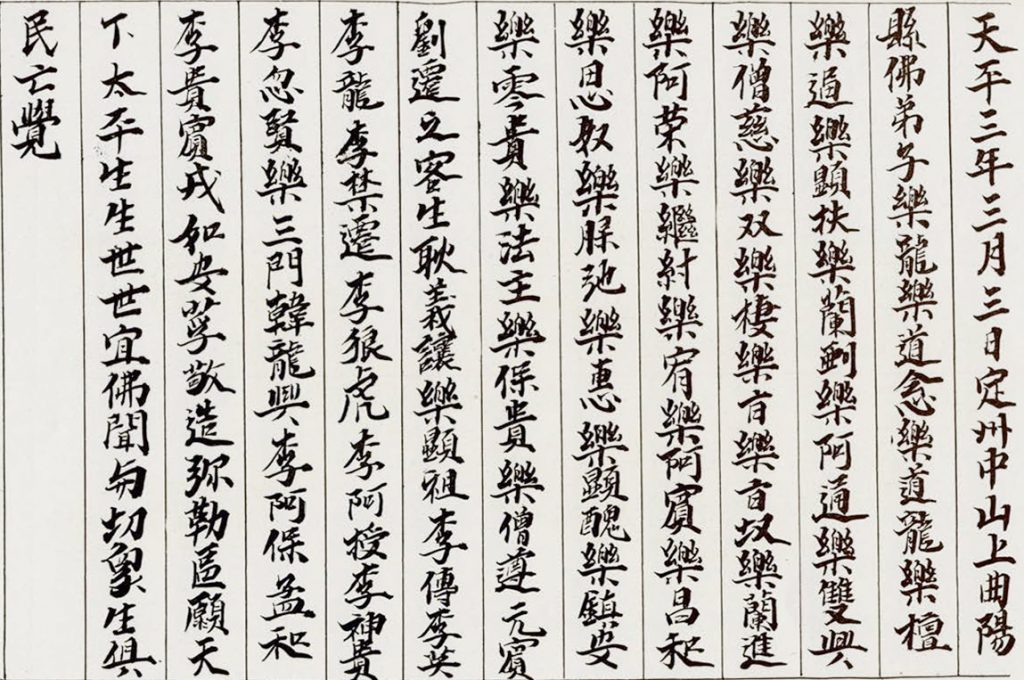

On the reverse of the aureole are outlined fifty-eight small Buddhist figures, each with its name, and there is also, near the bottom, an important inscription, telling us of the circumstances and purpose of the erection of this monument. A somewhat free translation will perhaps be of interest in helping us to understand the motives and beliefs of the devout men who erected this statue in honor of their faith in the days of the Northern Wei.

To begin with, the date is given, and it appears that this statue was dedicated on the fifteenth day of the seventh month of the first year of the year-period known as Hsi-p’ing, of the North Wei dynasty; in other words, during the year 516 of our era. The inscription then goes on to say:

“The lack of religious teachers renders it necessary to expound the teachings of the Buddhist faith through the medium of expository works. Sculpture has been the means whereby the divine truths have been made manifest.

“The coming of Buddha is the opening of Brahman, which is the indispensable key to the understanding of the Doctrine. An immaterial, invisible, and immortal soul undergoes existence in a body which is material, visible, and mortal. In the course of a succession of such existences the Buddha passed through all the many different stages of transmigration, from the lowest spheres of life to the highest, practising every form of asceticism and exhibiting in all his incarnations the utmost degree of charity and unselfishness. His Bodhi [Intelligence], the characteristic of the Buddha, was said to be living at the same time under three different manifestations; essential Bodhi, reflected Bodhi, and practical Bodhi. The mode of existence of the Buddha is that of absolute purity and completeness through numberless transmigrations.”Owing to this fact and in order to give the people of the Central Flowery Kingdom the opportunity of understanding the holy truths, the district chief, Chang K’ien-pai, of San-yang [in the province of Chih-li] and thirty-seven of his kinsmen have sculptured with great respect this stone statue of Mi-li Fo [Maitreya Buddha].”In honor of His Imperial Majesty . . . and for the expression of the mighty power and virtue which reveal themselves in the sacred doctrines and divine reflections of that mode of existence which is absolute purity and absolute completeness. . . .”To the memory of my parents and in the service of Buddha. Respectfully inscribed by Chang K’ien-pai and thirty-seven other.”

(Here the names follow).

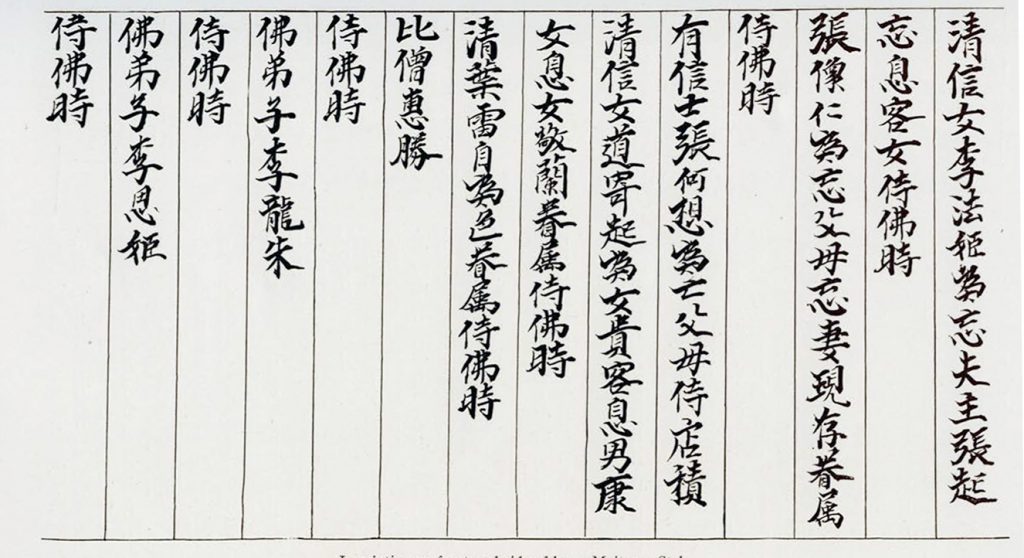

The Bronze Maitreya

As already intimated, the small bronze gilt statuette of Maitreya so closely resembles the large stone sculpture just described that most of what has been said of the one will apply with equal force to the other, and consequently need not be repeated. There is the same posture, a standing one, with the hands in the same position and symbolizing the same actions. The garb is precisely the same, and the aureole is similar save that there are no small Bodhisattva figures upon the reverse as is the case with the large stela. In short, both figures, as even a cursory inspection shows, belong to precisely the same school and represent the same Buddhist personage, Maitreya, the “One who is to come.”

Like its larger companion the smaller statue is inscribed, to the following effect:

“Third day of the third month of the third year of T’ien-p’ing [537 A.D.].2 For the temple at the summit of Chung-shan [Middle Mountain] at Ting-chou [Chih-li province].”

Here follows a long list of subscribers who contributed to the cost of the statue, and then the inscription goes on . . . “have offered and worshiped this venerable statue out of a desire for peace to the whole earth and in the sincere hope that future generations, treading in the footsteps of their ancestors, will continue to trust and reverence this Buddha, who will in turn vouchsafe to them his divine protection.”

Both of these figures were formerly in the well known collection of the late Viceroy Tuan-fang. The smaller one for a long period previous to its acquisition by His Excellency was one of the principal treasures of a temple in Ho-nan province. The late viceroy tried ineffectually during a number of years to purchase it, and it was finally only by undertaking to rebuild the entire temple, which was falling into decay, that the indefatigable collector was able to persuade the Abbot to part with his treasure. This little anecdote well illustrates the high value placed upon such works of art in the land of their origin, where they have long been understood and appreciated at their real worth.

C. W. B.

1 The Sapta Ralna, gold, silver, lapis lazuli, rock crystal, rubies, diamonds or emeralds, and agate.

2 The North Wei dynasty had come to an end two years before, dividing into an Eastern and a Western portion. The year-period of T’ien-p’ing was the first of the Eastern Wei.