An Account of Explorations in Venezuela

The journey which I am about to describe had two objects in view; to make a geographical survey in the Sierra de Pei*. of Venezuela and to obtain an account of the native inhabitants of the same area, together with collections to illustrate their arts and crafts. The results as far as they relate to the geographical part of my work will be published in the Geographical Review of the American Geographical Society. This paper aims to give a brief account of the journey, with special reference to the Indian tribe which I discovered inhabiting the Sierra de Perijá.

On May the first, 1918, I left New York on board the steamer Maracaibo of the Red D line bound for Maracaibo. Having written the Venezuelan Government previous to my departure, I found a letter from the Minister of the Interior of the Venezuelan Republic awaiting me at the dock in Maracaibo, in which letter, by presidential decree, the military and civil authorities of the district in which I was to work, were called upon to aid me in all matters. The letter proved invaluable in many ways and I have reason to he grateful to the generous policy of the officials in Caracas in allowing my baggage and instruments to enter duty free and in ordering the local government officers to further the interests of the expedition. These same courtesies were shown me in Venezuela on previous expeditions to other parts of the Republic and are indicative of the interest taken in scientific research by the authorities in Caracas.

Image Number: 27237

After disembarking in Maracaibo, my first act was to call at the office of the Caribbean Petroleum Company. This concern, with main offices in Philadelphia, is working the oil fields on both sides of Lake Maracaibo and has one drilling station at the very foot of the eastern slopes of the Perijá Mountains. Thanks to introductions given me by the Philadelphia office to its local representatives, I was provided with every aid, and enjoyed the hospitality of the Caribbean Petroleum Company at a small settlement called La Horqueta, two days’ travel from Maracaibo, where I made temporary headquarters previous to the exploration of the mountainous districts. The kindness shown me by the various officers of this company was greatly appreciated and the success of the expedition is mostly due to their interest and that of the Venezuelan Government in the undertaking.

From Maracaibo to La Horqueta one passes through a highly interesting plain. Briefly it may be said that the trip takes two days on horseback and that one first rides over an arid desert, until finally, at Monte Verde, a strip of virgin woods is encountered. The trail here is very narrow and gloomy, and the woods abound with tigers, jaguars, wildcats, monkeys and deer, while birds of all descriptions interrupt the hush of the forest with their cries. For many hours one rides along without seeing a fellow man, and it is only at the crossing of the Palmar River that habitations are encountered. Here also one is likely to see a Goajira Indian or two from the great peninsula to the northward. The Goajiras are in the habit of indenturing their young boys to various landowners of the district of the south, so that the occurrence of these pureblooded aborigines in an outlying region is quite common.

After crossing the Palmar River, which in the rainy season is a somewhat hazardous feat, the forest continues for many miles, until one finally reaches a rolling plain, covered with savanna grass, and studded with scattered habitations. When I had reached this plain, the mysterious Sierra de Perijá loomed up. It would be hard to describe this mountain range. One seldom gets a good view of it and the peaks are covered with eternal mists. While the altitude of the mountains is not sufficiently high to make them snow covered, the fogs and mists at times would almost make one think that the summits were covered with snow. On clear days one can see that the mountains are densely wooded up to their very summits. However, clear days are few and far between during the months of May, June, July and August, when I was there, as these months, as well as the months of October and November form the rainy season. I might incidentally state, that the rainy season offered but very few additional difficulties on the trip, as travel over the Indian trails in the interior of the Pei*. Mountains is incredibly hard in the dry as well as in the rainy season, and the rainy season therefore makes but little difference. Before coming to the settlement of La Horqueta, one reaches the historic little town of La Villa de Rosario de Perijá. The town is smaller than its name, but the ruined foundations of many houses testify to its former importance in the days of the conquistadores when La Villa—as the town is generally named—was the starting point for many a raiding expedition to the Indian territory to the south of the Rio Negro. A quaint old church, perhaps the oldest church in the entire State of Zulia, makes La Villa well worth visiting, and the ancient and pretentious Spanish architecture of many of the houses forms a startling contrast to the huts of the countryside.

Image Number: 27239

Upon arrival at La Horqueta, my first work was the procuring of men and animals. Thanks to the Caribbean Petroleum Company, I was obliged to purchase but few horses, as I needed pack animals only for the transportation of my baggage to Machiques.

From La Horqueta I rode to Machiques, a new town of 2,000 inhabitants. This journey is generally made in nine hours. I had been told that it was in this settlement that I could gain some information regarding the Indians of the Sierra de Perijá. And so it turned out to be. For here I found a Senor Eleodoro Garcia who owned a cattle farm some two hours’ ride to the westward of Machiques, where occasionally Tucucu Indians from the mountains would come and work in exchange for such commodities as hoop iron, cutlasses, beads, iron cooking pots and axes. The Tucucus are a very shy race and only came to Mr. Garcia’s property when they were especially in need of ironmongery. Even then they did not stir in the direction of Machiques, but seemed to feel secure only in the comparative isolation of the cattle ranch. It appears that the Tucucus proper live many days’ travel in the southward, but the particular Tucucus who frequented Mr. Garcia’s ranch had had trouble with the other members of their tribe and in consequence had taken up their abode with the Macoas, among which later tribe I ultimately made my headquarters.

I might state here that the researches of this expedition proved that the Tucucus, the Irapeños, the Pariris, the Macoas, the Rio Negro and the Rio Yasa Indians all belong to the great Motilone family. The various subtribes derive their names from the rivers to the south of Machiques, the headwaters of which they frequent. For many centuries the Motilones have proved to be a mystery and the information we have of them, in ancient and contemporary literature, is very scant and for the greater part untrustworthy. They are today regarded with great dread by the Venezuelans, who are unwilling to penetrate into their mountain retreats, a fact which is perhaps not to be wondered at when one considers the savage reputation that was given to the Indians by the early settlers. Perhaps the clearest proof of this fear can be found in the mention of the Motilones by A. Ernst who states “The Motilones are an almost unknown tribe, which, since the time of the Conquest, have remained in a completely savage state, living on the humid mountain slopes of the frontier between Venezuela and Colombia. . . . There are no means to make them give up the life of savage thieves to which they are accustomed. . . . No one has, up to the present time, seen the plantations of the Motilones, nor known with certainty if they have any fixed abode. . . . Lopez (on his map of Venezuela, Madrid, 1787) adds to their names the notice ‘the worst Indians that exist,’ which, even in our days is the current opinion of the inhabitants of the neighboring regions.” This quotation from Ernst is but one mention making clear the great uncertainty which exists regarding the Motilones, but there are several mentions in a like vein in other descriptions of the region and its inhabitants. I, therefore, considered myself especially lucky to have a chance to study the Macoa subtribe at first hand and to form a collection of the objects used by them, and a vocabulary of their language.

Image Number: 27206

Thanks are due to Mr. Garcia for taking me from Machiques to his cattle farm where I had the opportunity of meeting the Tucucus and of requesting the latter to make arrangements for me to visit the Macoa tribe. I thought at first that this visit was going to be an impossibility, as the Tucucus, who spoke a fair amount of Spanish, seemed reluctant to undertake a special trip to their homes to discuss the matter and obtain the required permission. However, in the end, encouraged by presents, they departed and returned after a week with the information that the Macoas said I might come to their village, providing I was not accompanied by more than one other man. Through Mr. Garcia, I managed to obtain a faithful “peon” who remained with me during my sojourn among the Macoas. This man, Manuel Peñaranda, proved to be an invaluable companion with plenty of “nerve” and a clear head in an emergency.

As for the other inhabitants of Machiques, when it was learned that I intended not only to go to the Macoa country, but to remain there for a considerable time, the consensus of opinion seemed to be that I would not return and the number of sorrowful farewells that were hidden me seemed limitless.

Image Number: 42536

When finally the Tucucus returned with the welcome news that I could visit the Macoas, my baggage was all arranged and I lost no time in getting started. As has been said, the baggage had to be transported on the backs of the Indians, while I found that a camera, an aneroid barometer and a compass were about all I personally could carry. At that, the traveling was intensely difficult and the Macoas appeared to have made the trail to their haunts as undiscoverable as possible. Their reason for this probably is their reluctance to have neighboring tribes, such as the Rio Negro and the Pariri Indians, know of their whereabouts. Furthermore, they possibly have an inherent fear of raids by Venezuelans. While the latter have not taken place for the last fifty years, it is quite probable that the older members of the tribe still remember accounts given them by their fathers of atrocities committed by the Venezuelans in years gone by, before the government adopted the wise policy of allowing the Indians to live without molestation.

For two days my little party, consisting of the eight Tucucu Indians with my baggage, Manuel Peñaranda and myself, traveled in the mountains before coming to the Macoa settlement. At first the trail followed the bed of the Aponcito River, a tributary of the Apon. On this trail we frequently had to wade in the river itself, this being the only means by which the higher altitudes could be reached. Again, the trail sometimes led towards the precipitous crest of a mountain, so that at times the only manner in which one could proceed would be to clutch the giant creepers that are pendant from the trees, and literally haul one’s self up the trail. At the end of the first days’ travel, a temporary hut was built from sticks and palm trees, and my party, including myself, spent the night on the ground. By this time, a high altitude had been reached, and I experienced the cold of the Sierra de Perijá for the first time. When I say that during my entire stay in the interior of this mountain range I was always forced to sleep under two blankets and even then suffered from the cold, the reader may have a fair idea what a sojourn in this humid region means. Practically every day the mists roll down the mountains at about midday, and one spends the balance of the day in an enveloping fog which makes one forget that the equator is but ten degrees distant. I am not a botanist but the vegetation in the interior of the Perijá Mountains struck me as being more subtropical than tropical, and in the higher altitudes—as I subsequently found out to my cost—practically no game is found with the exception of the spectacled bear.

Image Number: 27209

Continuing the next day, we reached the Macoa territory and began to see evidence of clearings and plantations. The latter part of the trip was somewhat easier, as the trail now descended towards the lower altitudes inhabited by the Indians. At last, the Tucucus told me we were close to the Macoa village, and they accordingly began to shout so as to let the Macoas know we were coming. The settlement of the Macoas is scattered, no two huts being found in close proximity. In fact, these Indians appear to take pleasure in living as far removed from each other as possible. which may be due to the eternal fights they wage amongst themselves. Each hut is on a separate hilltop, so that, while the entire village is within hailing distance, it often takes as much as half an hour to go from one abode to the other, by first descending one slope and then ascending the other. The average altitude of the Macoa settlement is 3,600 feet. It must be stated that the Macoas are nomadic in their habits; they have been living in the present site for a few years, hut I was given to understand that they would probably move, shortly after my departure, and travel further westward, which would give them an even greater isolation. Their clearings and plantations, in which they grow yucca, sweet potatoes, corn, bananas, plantains and yams, are also far removed from their huts, so that it frequently takes a man the half of a day almost to walk to his farm. Why this is so, when the hill slopes directly underneath the Indian’s abode are just as well adapted to agricultural purposes, I cannot state, and inquiries failed to give a logical explanation.

The probable reason for the nomadic habits of the Motilone tribes is that they are constantly at war with neighboring tribes. The dreaded enemies of the Macoas, for instance, are the Rio Negro Indians, and frequent were the solicitations of the Macoa chief to have me accompany his men on an expedition against the inhabitants of the headwaters of this Rio Negro. As an incentive, the Macoa chief told me that he would give me all the booty in the shape of bows and arrows that they expected to secure. While the offer was flattering, I suspected it was due rather more to the fact that the Macoas expected my firearms would strike terror in the hearts of the Rio Negro Indians and secure them an easy victory, than from confidence in my personal attributes as a warrior.

On the arrival at the first Macoa hut, the Indians of this tribe appeared to spring from the very earth and quickly surrounded me with every evidence of good intentions. This, to the explorer, is always the nervous period, for Indians have been known to take a sudden dislike to a stranger. If their first greeting is kindly, the chances always are favorable that the explorer will have a pleasant stay, providing he does not abuse the hospitality extended to him.

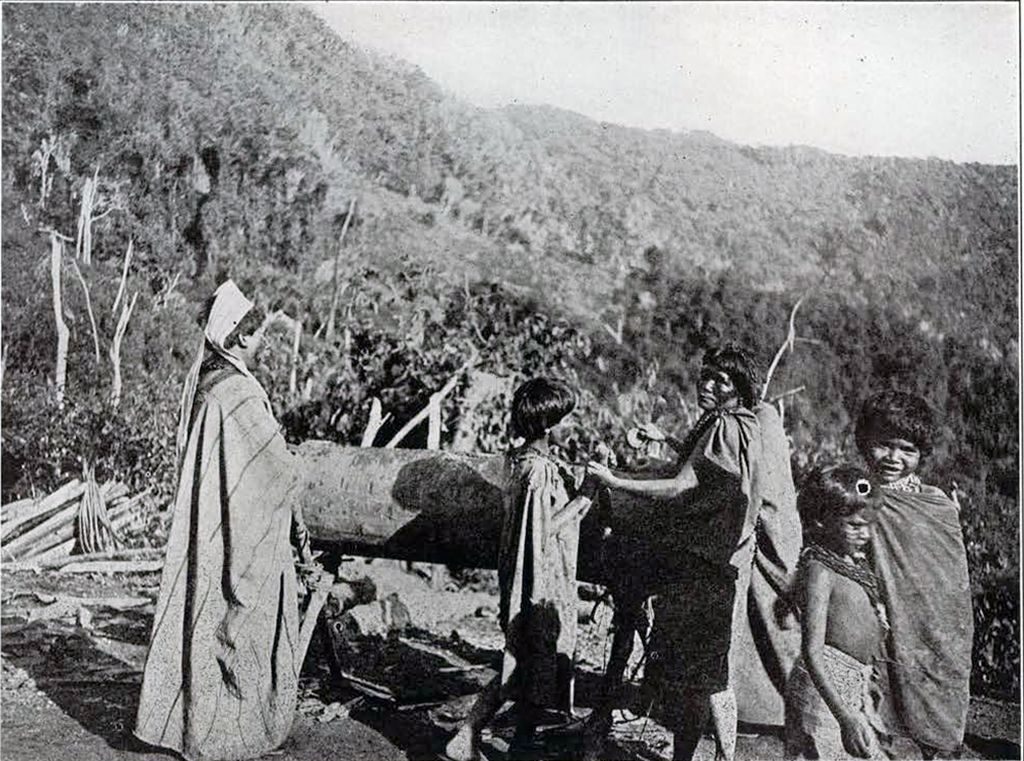

Image Number: 27238

The friendliness of the Macoas was so great that it was a trifle embarrassing. Within a short while, the entire tribe had gathered around and were examining me with the minute attention that a biologist might give a new species of animal. My clothes were touched and examined, and several of the men put their hands on my face and hands, exclaiming “kezré,” a word which I subsequently discovered meant “white.” My eyes also were scrutinized with great care and the word “shekáka” frequently repeated. This word, I afterwards found out, means “blue.” Strange to say, my companion, Manuel Peñaranda, with his darker eyes and skin, did not come in for any attention at all, and the Indians generally left him severely alone during our stay in their territory. From this lack of curiosity regarding Peñaranda, I deducted that possibly the Macoas are not as unacquainted with the Venezuelans as the Venezuelans think, and that they may have frequently observed Venezuelans from hiding places when the latter were unaware of their presence. Be this as it may, the novelty of my person never wore off during my stay among the Macoas. At times, in fact, their curiosity was decidedly embarrassing, especially so when a number of the men would gather at my bathing place in the brook to observe the odd performance of my daily bath with an interest that was apparently divided between my strange appearance and my equally strange occupation, for the Macoas, who are not addicted to personal cleanliness, only take a bath when they are caught in a rainstorm.

The first thing the Macoas, aided by the Tucucus, did for me was to build me a hut along the same lines as the huts inhabited by them, but of far larger dimensions. Not only were the Indians interested in my general appearance, but my size also filled them with curiosity. This can be understood when I mention that the average height of the Macoa men is five feet one inch, while the average height of the women is four feet eight inches, whereas my height is over six feet. As a result, they seemed to reason that the tall stranger needed a hut far larger than those they inhabited. The entire male portion of the tribe turned out to build my abode. Several of the men betook themselves to the neighboring hill slopes to fell trees for the posts and beams; others made trips to the lower altitudes to obtain the palm leaves from which the roof was thatched, while another party went in search of the pliable creepers that served in lieu of nails or ropes to fasten the poles together. Again, some of the other men cleared the ground in front of the hut of weeds and bushes. Within two days, which I spent in another hut, my house was finished and the chief informed me that it was ready for me. During my entire stay among the Macoas, I found this spirit of willingness manifested and while the Indians were always pleased to receive trade goods in exchange for their work and for the specimens I collected, they, with one or two exceptions, appeared to be happy to serve the stranger in their midst and to take a pleasure in providing him with food.

Once installed in my hut, the daily routine consisted of collecting specimens, learning the Macoa language, compiling a vocabulary, and photographing the Indians in all phases of their life. At times the carrying out of this routine work proved hard. My hut was never free of Indians from the day it was erected until the day I departed. From dawn until nightfall, various men and women would be hanging around, and while this was useful when it came to learning the language and studying the customs, it at times interfered with writing and photographic work. The taking of photographs was an unending source of interest to the Macoas and it became necessary for me to request the chief to have a stockaded enclosure built, so as to form a room in one part of the hut, on the plea that the children would then be unable to interfere with my work. As a matter of fact, it was as much to prevent the adults from interfering as it was to escape from the attentions of the children. The stockade was accordingly built and when I wished to do any work where interference or conversation proved troublesome, I retreated to my stronghold.

Image Number: 27232

The Macoas are quite unlike the majority of other South American aborigines. Perhaps the greatest difference lies in that they possess a very strong sense of humor and would laugh on the slightest pretext, waxing especially hilarious whenever another member of the tribe met with an accident. Again, while the Macoas had decidedly warlike tendencies, they quarreled among themselves only when drunk with chicha. Furthermore, the men of the tribe tilled the fields, made basketry and other artifacts and followed several occupations which in other parts of South America belong by the women exclusively. From what I could gather through the Tucucus, the Irapeños, Pariris, Tucucus, Rio Negro and Rio Yasa Indians have all practically the same customs as the Macoas and use the same inventions. In consequence, a study of the Macoas may be taken to illustrate the ethnology of the other tribes as well.

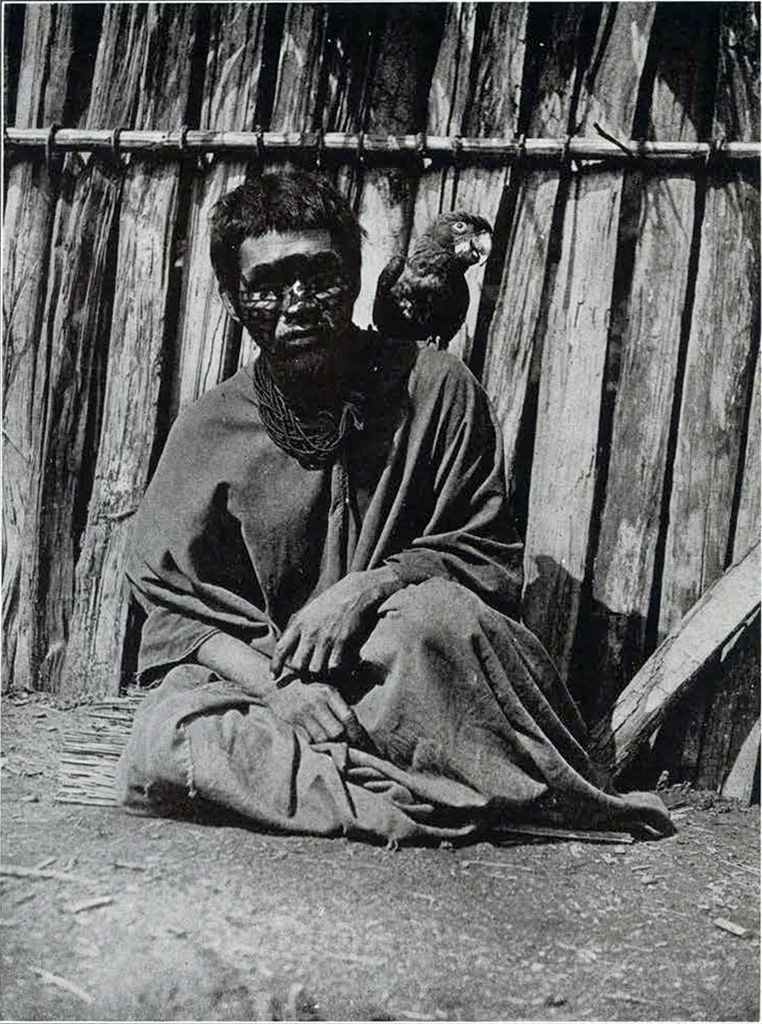

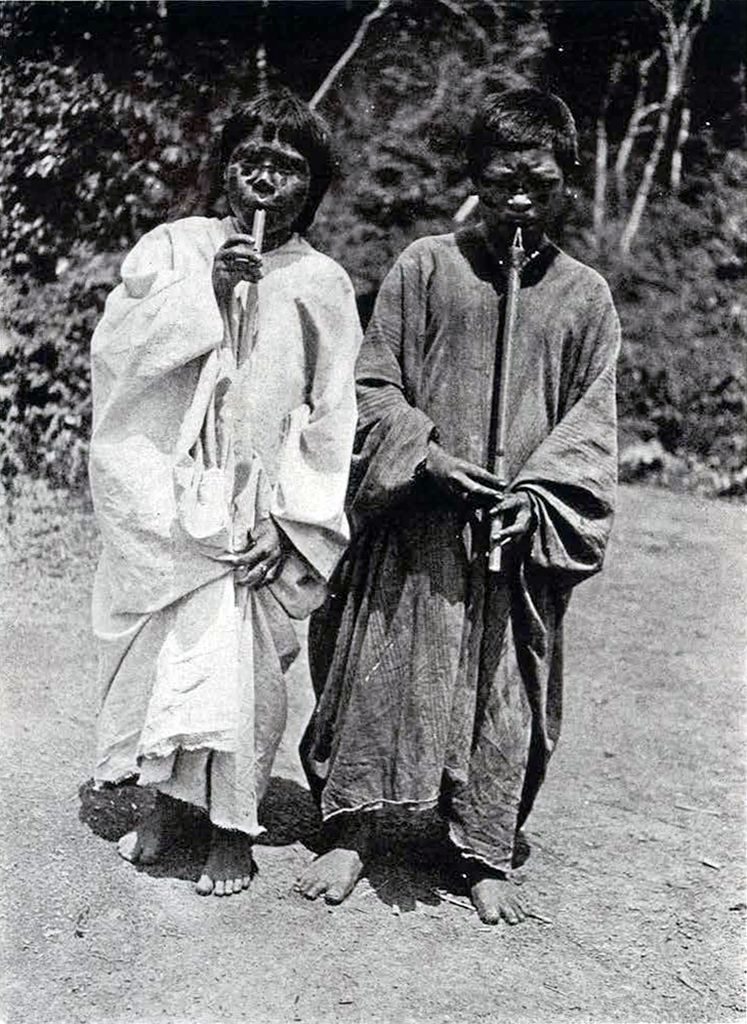

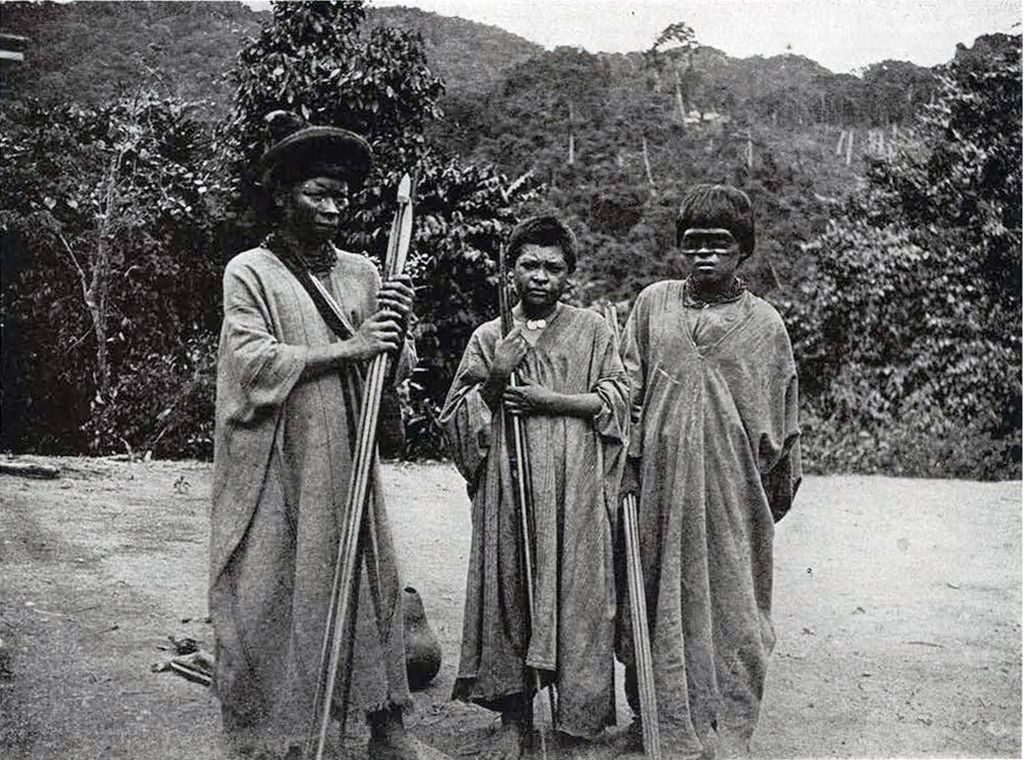

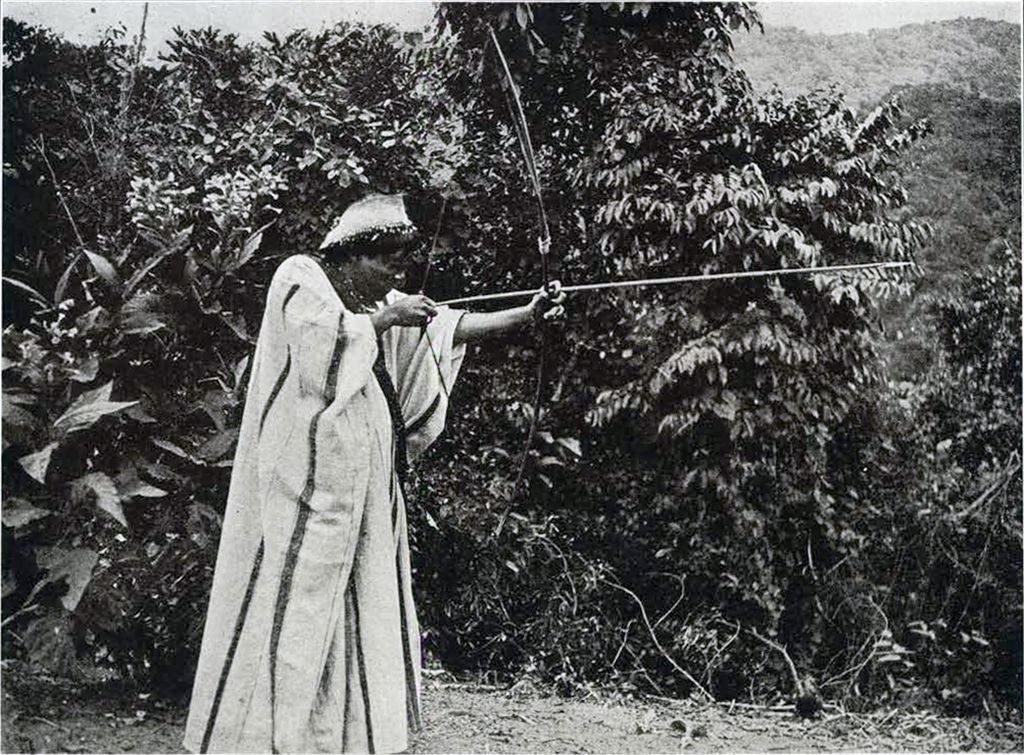

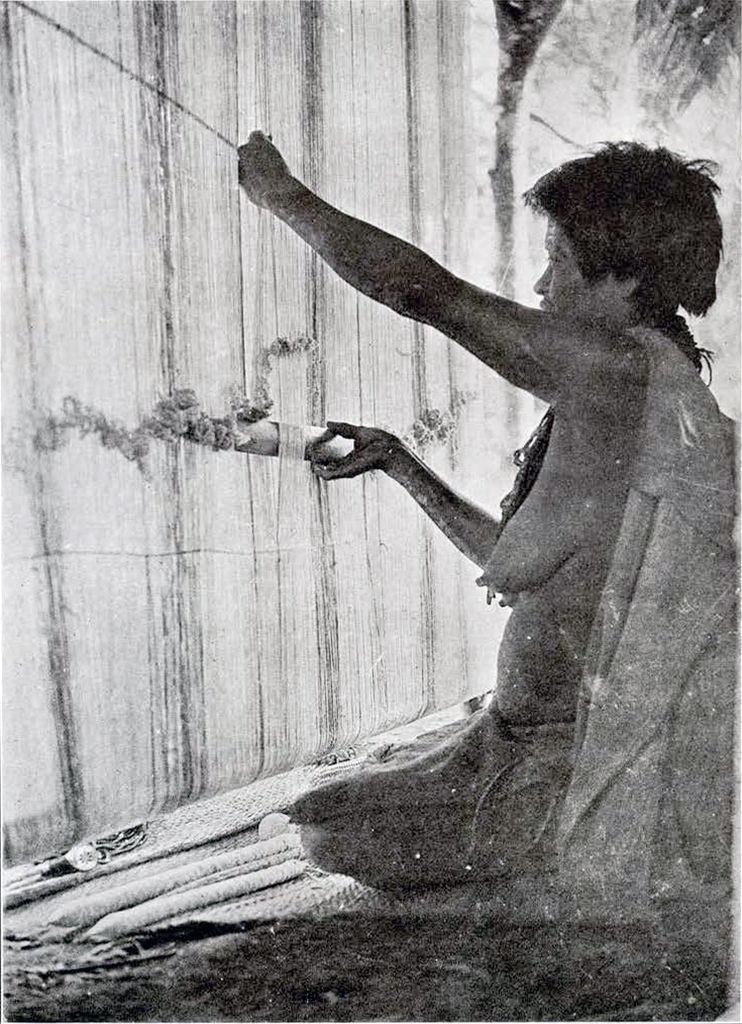

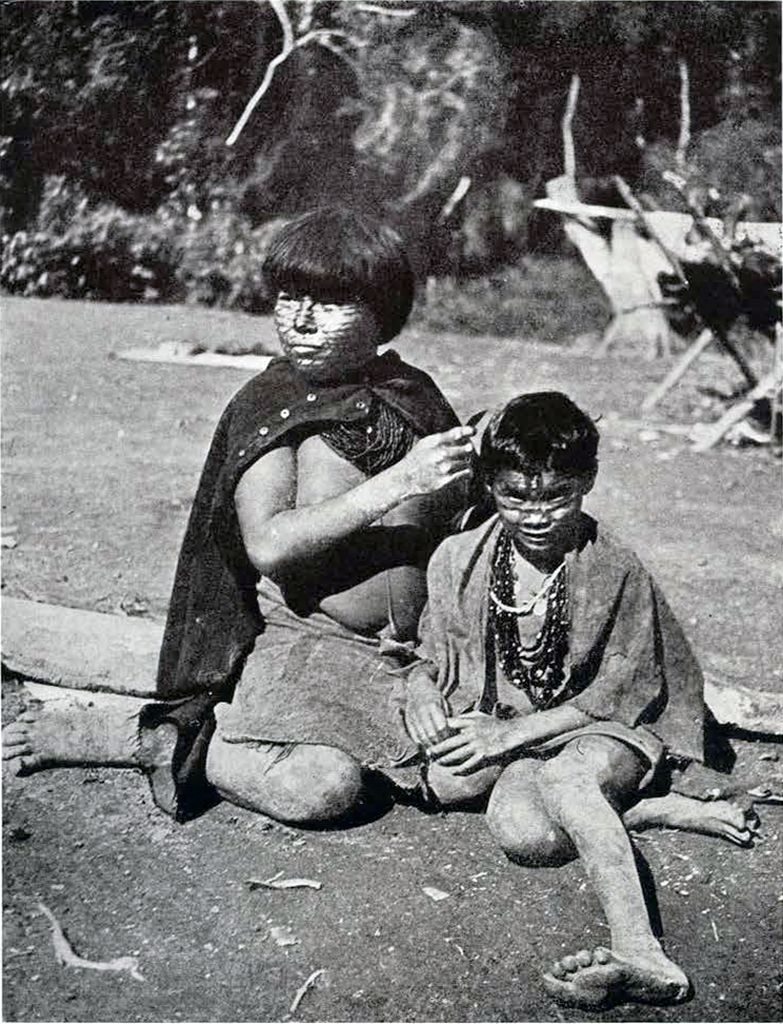

Stockily built, with short cut hair, high cheekbones, and somewhat unclean in their personal habits, the Macoas are not attractive to look at, especially so as the intricate designs they paint on their faces are apt to give them a gruesome appearance. Men and women alike are seldom seen without face paint, for which black, brown and scarlet pigments are used. The little children even are decorated in this manner. It is of course not the purpose of this paper to go at length into the various ethnological details of the Macoas, and I must therefore refrain from telling in detail of their customs. Briefly, it may be said that they wear heavy clothes, as the cold of the region they inhabit makes this protection necessary. The men wear a one piece robe, resembling a gigantic sack, with holes for the arms and the head. This robe is woven of cotton, grown on the mountain slopes and is made by the women of the tribe. As personal adornment, the men wear a woven head dress, which, in the case of the more important members of the tribe, is ornamented with colored seeds. Also, the Macoas were at one time in the habit of making pleated straw hats with a conical crown, the latter being surrounded by a band of highly colored toucan feathers. There were but two of these hats in existence when I visited the Macoas, as for the last number of years they have lived in a region where the straw from which the hats are made is not found and it is quite likely that the making of these head ornaments will soon become a lost art. One of the hats was secured, together with the surrounding band of feathers, for the University Museum. In addition to these two types of head dresses, the personal ornaments of the male Macoas consist of strings of seeds, a small black seed, and a large scarlet seed being the two kinds principally used, although necklaces and bandoliers were also made of a grayish white seed. Sandals are not worn and are unknown.

The Macoa women wear a dress consisting of a loin cloth and a mantle. Frequently the mantle is left off, the upper part of the body remaining nude during the daytime when the cold is not so intense. No head dresses are worn by the women, but they frequently decorate their heads with crowns of scarlet and black seeds. In addition to this, necklaces and bandoliers of seeds are worn. Girls go nude until they are about two years old and then are dressed in a miniature edition of the robes worn by the older women. Boys remain in a state of nature until about their fifth year, after which they are provided with the same style sack that is worn by adult men. All children wear necklaces, practically from the day of their birth.

Image Number: 27226

The Macoas are unacquainted with hammocks and sleep on pleated straw mats, which are spread on the ground. They make fire with the drill method and almost always keep large logs burning. The preparation of their food is highly primitive, and generally consists of placing their game, plantains and yams in the coals and eating them half raw. In consequence, stomach troubles are not uncommon. Outside of this, disease is almost unknown among the Macoas, and death, so far as I could learn, occurs only from old age or from wounds received in battle.

For arms, the Macoa uses various types of arrows, which are discharged by bows, blowguns being unknown to them. Spears and clubs also are not found among these aborigines. The Macoa boy is initiated in the science of archery at an early age, it being no uncommon sight to see small boys of five waddling about with a miniature bow and arrows. One of the favorite boys’ games amongst this tribe consists of shooting at each other with arrows that are tipped with corn cobs. Besides this, a favorite boys’ game is the making of string figures with a cord, very intricate designs being produced. Our expedition photographed and classified a number of these figures, to the huge delight of the boys who took an intense interest in having pictures taken and seeing the negative afterwards.

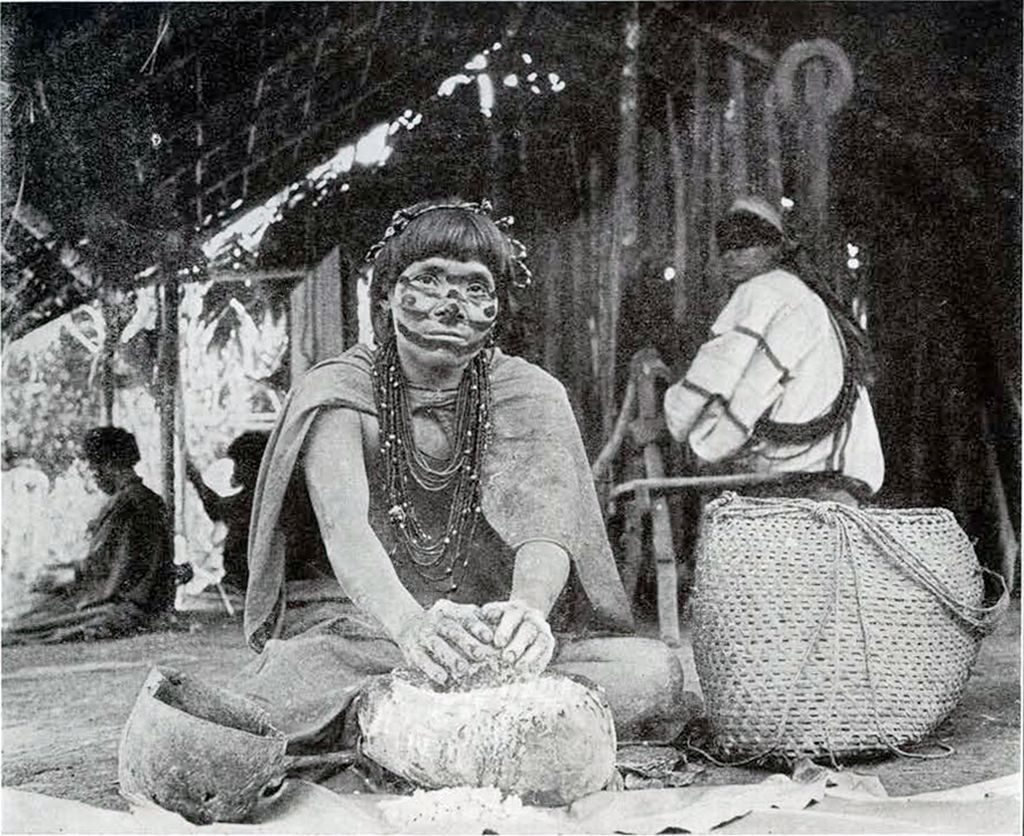

Perhaps one of the most interesting customs of the Macoas is the chicha feast. They indulge in this feast almost every month when the moon is full, and it was my good fortune to attend one of these feasts and my bad fortune to attend a second one afterwards. The first preparation for the feast is the blowing of conch shells. This is done with great perseverance and monotony for an entire afternoon. That same night the wife of the giver of the feast grinds the maize from which the chicha is prepared. This grinding is done on a flat mealing stone. The following morning the crushed maize is tied up in small bundles, enveloped in leaves and cooked for about an hour. The maize pellets are then laid in the sun to dry, after the wrapping has been removed and they develop a covering of fungi through partial fermentation. The day previous to the feast these pellets are placed in a hollowed out log, the “kanoa,” together with crushed ripe bananas and crushed sweet potatoes. Water is poured on this mixture and fermentation commences immediately. The following day, amid frantic blowing of conch shells (in fact, the chicha music has been going on during all the days of preparation) the feast commences. Special pains are taken by the Macoas to decorate their faces with painted designs and even the smallest infants are dressed for the occasion. At first, the merry making is mild. Some monotonous singing takes place, but the participants pay more attention to the imbibing of the liquor than to the dancing and the singing.

Image Number: 27229

After drinking for about four hours, the Indians generally become quarrelsome and want to fight among themselves. During the first feast I attended two brothers made an attempt to kill their elder brother, the chief of the tribe, and had it not been for interference by other Macoas, would certainly have attained their object. I made an attempt to photograph this occurrence from the outskirts of the fight, but, as it was almost dark, did not succeed in getting a picture. That same evening, an Indian, for some unknown reason, became jealous of his wife and cut her over the head with the sharp edge of his five foot bow, producing three fearful gashes which I was obliged to sew up the next morning. Needless to say, while all this was going on, Peñaranda and I were nervous, as we did not know if the Indians might take it in their heads to start a fight with us. It is probable that they had no such intention, but, just the same, one does not appreciate a drunken Indian who waves an enormous arrow under one’s nose, even if this is done in a friendly spirit.

About midnight the Indians were extremely drunk, men, women and children alike, it being their custom to give chicha even to the smallest infants. About this time the dancing begins, and it is no uncommon sight to see a Macoa divest himself of his robe and dance naked. By now the Macoas were extremely amiable, maudlin in fact. From midnight until dawn the dancing in the moonlight went on, those who dropped from sheer drunkenness being pulled to their feet and encouraged by those that were less intoxicated. It is a point of etiquette among the Macoas to finish the entire brew of chicha and by dawn one would see the few members of the tribe that were still able to walk making a weary attempt to empty the wooden troughs. Finally, the last member of the tribe succumbs to intoxication and silence reigns over the clearing where the feast took place, the ground being strewn by Indians in all attitudes of drunken exhaustion.

Image Number: 27211

The second chicha feast which I witnessed proved to be a trifle more thrilling than the first. Two of the Indians had harbored a grudge against their wives and declared at the very offset of the feast that they were going to kill them with arrows. As the Macoas had not yet imbibed enough chicha to make them unreasonable, I interfered and argued with the men, telling them that there were but few women in the tribe and that there would be a serious shortage if they killed the two. My arguments finally prevailed, and the women in question wisely absented themselves for the balance of the feast. Shortly after this, two youths began a fight with their bows—the bow used as a quarterstaff being a favorite weapon—and succeeded in giving each other several gashes on the head. Finally, some of the Indians, who by now were very much excited, brought up the subject of the fight at the previous chicha feast when the two brothers attempted to kill the chief. Some time before the fight I had been doctoring the chief, who was a feeble old man, for dyspepsia and had succeeded in improving his condition. The Macoas now claimed that it was due to this improvement that the chief had become belligerent and had started the fight with his two brothers, as, previous to my coming, he had always been content to allow his brothers to have their way. In consequence, the Macoas reasoned that if I had not given the chief medicine, the fight would not have taken place. Although this occurrence convinced me that the Macoa character is not dependable in a chicha feast, I had little difficulty in persuading them that I really had no part in the quarrel.

The Macoas are monogamous with the exception of the more important members of the tribe who sometimes have two women. The chief of the tribe had two, and two of the older Macoas were also provided with two wives. Yet it cannot be said that these Indians are polygamous, as the elder of the two women is generally considered as the wife, while the younger acts more in the capacity of servant to the other.

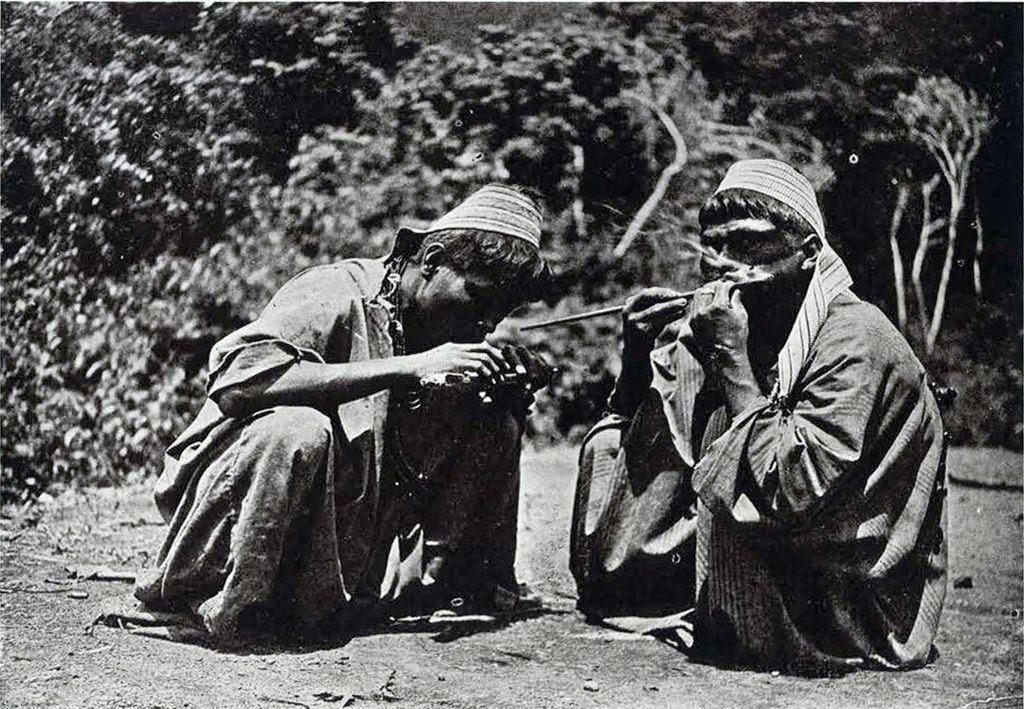

Music plays a large part in the life of the Macoas. Their instruments are restricted to flutes and conch shells; instruments of percussion, such as drums, being unknown. Various types of flutes and panpipes are used. The only instruments played by the women are the panpipes, and these are not played by the men. It cannot be said that music as made by the Macoas is especially thrilling, and they play the same monotonous tune over and over again. I succeeded in varying the monotony by introducing jewsharps which I had among my trading goods, and while the Macoas were of course not acquainted with this instrument, they proved apt pupils and soon learned to reproduce their tunes. The jewsharps soon became broken, whereupon the Indians hung the instruments on their necklaces and were just as pleased. I wished that the same results could have been attained with their flutes which were constantly being played upon.

The Macoas excelled especially in the making of baskets of various types. The weaving of baskets was done by the men, although this occupation is generally followed by the women among other South American tribes. The larger baskets were used for transportation of foodstuffs and of calabashes filled with water, and were suspended on the backs of the carriers from woven cords which went over the forehead. Even the smaller girls were made to carry loads in this manner, and it was very common to see an infant of five bring in the day’s water supply, frequently transporting two enormous calabashes, with perhaps thirty pounds of water, in a basket. Other types of baskets were made and used for all purposes, practically all the household goods of the Indians being stored in this manner. The Macoas are extensive users of gourds and calabashes for all culinary purposes and always have large supplies of these on hand. Gourds are used as food bowls, cooking bowls, and spoons, while the calabashes are used for the storage of foodstuffs. The powdered face paints also are kept in small gourds.

The study of the Macoa language proved to be a fascinating occupation and one which was more amusing to the instructors than to the pupil. The Macoas would gather around whenever I produced my notebook and hurriedly call a Tucucu interpreter into service. I would give the Tucucu a Spanish word and he would then tell me the Tucucu word which was the same as the Macoa. This I would then write down phonetically, and it always delighted my audience when they discovered that I could repeat the word from my notebook. In all, some three hundred and fifty words and expressions were collected which may prove of future aid to a prospective traveler through the Motilone country.

The Macoas have but few religious observances. Certain ceremonials are followed in the case of burials and in going on the warpath. They believe in a supernatural being which they call “Kioso” and when it thunders, the Macoa looks up and says “Kioso ésop”, which, translated means “God is angry.”

After spending six weeks with the Macoas, I felt it was now possible to follow out the other object of my trip to this region. This was the making of a survey of the headwaters of the Apon and the Macoita rivers and the penetration of the more westerly regions of the Sierra de Perijá. Accordingly, I obtained four Indian carriers, of which two were Tucucus and two Macoas, for the transportation of my food supplies, and proceeded in a due westerly direction from the Macoa settlement, leaving Peñaranda and the bulk of my equipment in the hut built for me by the Indians. It was impossible to secure a larger number of carriers, as the Macoas were reluctant to go in the direction I indicated, claiming that it was a dangerous country, invested with hostile Indians, and a region to which they had never traveled. There were some traditions among them of a great battle that had been fought somewhere near where I wished to go, and one Tucucu spoke of a curiously shaped mountain in the base of which could be found an enormous burial cave. This information had been given him by his father, in years gone by and I subsequently was shown the peak which he recognized from his father’s description.

Image Number: 27204

Starting out with my four Indians, we followed an Indian trail for the first day of the journey until we reached the summit of a 6,000 feet high mountain which I had sighted from the Macoa village. This mountain was the limit of their previous journeys, the Indians said, and I could see on the days following that they were palpably nervous about the direction we were traveling in. We made a temporary hut on the first night and left a certain amount of foodstuffs behind which we expected to recover on our return. Due to my inadequate number of carriers, and to the almost insurmountable difficulties of the trail, the amount of foodstuffs we carried had of necessity to be but scant. Besides, I confidently expected to find game, as the mountain slopes below my hut in the Macoa settlement abounded with animals of all kinds and I had but to go out with a gun to return with flesh food for the day. On my journey, however, when I reached the higher altitudes, I found game to be nonexistent, with the exception of the spectacled bear, of which I saw many tracks. As bad luck would have it, despite all the tracks I saw and the claw marks on seed trees, I never actually sighted a bear. Had I done so, the Indians and myself would have had an ample supply of food for several days and we would not have been obliged to return when we did. According to the Indians, the spectacled bear affords but tame hunting; they told me that whenever one of these animals would sight an Indian, he would climb the nearest tree and remain there until he fell down, killed by arrows. The Indians said the bears never put up a fight.

After the first day, and until the end of the fifth day, when we turned back, it became necessary to clear a trail for our further travel. Progress in consequence became extremely slow and we would chop our way through the dense growth, be on the go all day long and by nightfall have made perhaps five miles in an airline. The mountains in the interior of the Sierra de Perijá have precipitous slopes, so that one might have to actually travel twenty miles to cover a distance of five miles. Again, travel with the Indians is trying and irritating when one is in a hurry to cover distance. This is due to the fact that an Indian, when going from one place to another, is easily diverted from his purpose. The sight of the track of a bear, for instance, will cause him to forget all else and he will, unless restrained, lose sight of the object of his journey and spend the balance of the day in pursuit of the animal, which has made off in an entirely different direction from the one the explorer wishes to follow. Somewhere else, the Indians may notice some reeds in the distance. It makes no difference that the leader of the party wishes to go due west; if the Indians wish the reeds in order to make a future supply of arrows, and the reeds are to the northwest of the planned route, all remonstrance fails, and the Indians get the reeds. The result of all this is that travel is exceedingly slow, unless one exercises a firm authority over the aborigines which is not advisable, as in that event travel might even become slower. Another very irritating Indian habit is the constant desire for food. It is almost incredible the amount of food they can consume at one sitting. I frequently shot a curassow (a bird resembling the wild turkey and weighing from eight to ten pounds) and saw it disappear among four men within half an hour after the bird was killed. When we reached the higher altitudes, and no game was to be found, complaints became noticeable by their frequency, and at last were so bitter that I deemed it best to turn back. By this time we were actually within sight of the curiously shaped peak at the foot of which tradition said the burial cave was to be found. Another day’s journey would undoubtedly have seen us at the mouth of the cave and in two days’ time we would have been on the summit of the last mountain range between Venezuela and Colombia. When we turned back we had had no food for one day and almost no food for the two days previous. It would be another day before we got back to our last camp, where a very small supply of milk tablets had been left behind and then one day more before we reached a camp where two small tins of beef and some yucca roots had been left behind. This camp once reached we were fairly sure of finding game.

Image Number: 42547

It may seem a small thing to the reader to hear of our doing without food for this short length of time, but, in reality, climbing mountains, scaling precipices and hacking one’s way through dense forests, on an empty stomach, is anything but enjoyable. Perhaps the hardest thing of all was the turning back when the objective was in view. Had the Indians been a trifle less surly, I might have attempted to force the issue and gone two days more without food, trusting to luck that, on reaching the cave, we might find animals of some kind.

It is quite probable, almost certain in fact, that this burial cave contains archeological treasures of the highest value. Our archeological researches, of which we cannot give a lengthy account in this general paper, proved without a doubt that the entire region had at one time been inhabited by the Arhuacos, a tribe of which a small remnant still lives in the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta. The Motilones, which includes the Macoas, were evidently comparative newcomers to the region and had either driven out the Arhuacos or had killed them off, probably only a short while before the Conquest. Researches by other archeologists have proven that a similar occurrence took place in the Goajira Peninsula directly to the northward, and that the Goajiras superseded the Arhuacos in this latter region. The burial cave, therefore, probably contains Arhuacan specimens, and as the Arhuacans were excellent workers in gold and had quantities of gold ornaments, it will be seen that the chances of this cave containing gold ornaments as well as burial objects of other kinds are very great. Two days before coming within sight of the peak in which the cave was to be found, the Indians had shown me certain regions where evidence could still be seen of former clearings. These clearings were of considerable age and were only distinguished from the surrounding woods by the fact that the trees were not quite as large and the undergrowth of lesser density.

So we turned back and retraced our way through the woods, up and down the precipices, and over the river beds. Despite the nonsuccess of the exploit, I had succeeded in viewing a new country and of making geographical observations in a region that had hitherto been left unvisited. Of other Indians we saw none, nor did we see any evidence that any of the mountains we passed over had been inhabited in recent years.

Image Number: 27208

After spending a few days more among the Macoas and consoling Peñaranda who had not relished his stay among the tribe during my absence, I decided to depart for the lowlands. My trading goods had all been used up, I had a representative collection of all the products of native industry. Furthermore, I felt that a longer stay might become dangerous. I had seen enough of these particular Indians to realize that their character was somewhat fickle and that their friendship of today might turn into their avowed enmity tomorrow. The novelty of my being among them had worn off, they were aware of the fact that the stock of trading goods had given out and another chicha feast was imminent. The thing to do, therefore, was to arrange for a number of carriers to transport the collections to the lowlands. It took thirteen men and two boys in the end to do this, and as the Macoas absolutely refused to undertake the final part of the journey, we were forced to leave some of the loads at a distance from Mr. Garcia’s cattle ranch until the Tucucus could make several trips to and fro and bring in the loads of the Macoas. It would be hard for me to say whether or not the Indians were sorry to bid me goodby. Some of them seemed to be, while others appeared to have the utmost indifference. For my part, I was sorry to see the last of my hosts, for with all the excitements we had had in the Macoa camp, I could not forget that the Indians had fulfilled their part, had given me food while living with them, had formed for me a wonderful collection to illustrate-their native arts, and last, but by far not least, had deposited me safely in the lowlands at the end of my visit.

A few words regarding the trading outfit used by me may not be amiss. In the first place, I had bought a supply of jewsharps, cheap jewelry, bead necklaces, pipes and loose beads in Maracaibo. This was supplemented by a quantity of cheap and highly colored calico and numerous bright handkerchiefs. A few dozen pocket mirrors were also included. Later on, when I sent a Tucucu or two to the lowlands, in order to keep in communication with the outside world, I arranged for supplies of heavy cotton cloth from Machiques. Due to internal strife, the Macoas have moved so frequently from place to place in the last few years that their cotton crops have been failures, and as a result they are very short of cotton for the weaving of their robes. The entire tribe was in rags and tatters when I came there and my gifts of cotton from which they could make new robes were greatly appreciated. The blankets I subsequently purchased in Machiques were also welcome gifts, and were highly prized by the older members of the tribe who feel the intense cold of the nights more acutely than do the younger Indians. Should any future traveler wish to penetrate this region, he is advised to carry with him a supply of hoop iron (from which the Indians fashion their arrow points), cutlasses, sheath knives, and large beads, in addition to the articles enumerated. A miniature talking machine might also be a welcome innovation to the Macoas, and the newcomer would undoubtedly rise in their esteem by playing selections on this instrument. I only wish that I had thought to bring one of these with me, as it not only would have given joy to the Indians, but might have proved a welcome relief from the monotony of the everlasting pipe music.

Image Number: 42544

After reaching the lowlands, my next undertaking was the making of an archeological survey with the view of gaining information on the pre-Columbian population of the region. I had been told of a small hill between Machiques and the Macoita River, within a short distance of the place where this river breaks through the mountains to gain entrance to the lowlands, upon which hill potsherds and other evidence of a former occupation could be found. The hill was named “Pueblo Viejo” and the name in itself was evidence that antiquities might be found, as it signifies “Old Town.” In consequence, I gave orders to Peñaranda to proceed to this place with a gang of laborers and to erect in a suitable spot a couple of huts which would serve to house my party. When these were completed, I left La Horqueta, where I had spent a few days to recuperate from the hardships of my trip to the Macoa country and to enjoy the comforts of civilization, and installed myself in one of the new abodes. The first thing to do was to make a careful examination of the terrain and to determine the best locality for the archeological work. It turned out that there was no digging to be done, as the hard and rocky soil of the sun parched savanna had not tended to preserve pottery specimens underground. The work, therefore, consisted of a careful scouring of the surface by my laborers and the picking up of all potsherds, stone axes, mortars and similar specimens. In order to do this as efficiently as possible, it became necessary to set fire to the dry savanna grass and to await a rain which would dissolve the resulting ashes. After this the work was easy and merely became a matter of good eyesight. At the end of the day I would go over the collected specimens and determine which were of value. During the day I would ride throughout the countryside with a view to discovering sites for future work, and while so engaged was fortunate in finding the site of a prehistoric cemetery and of several kitchen middens. At a future date, it is possible that these discoveries may result in the carrying out of extensive archeological work in this region. As has been stated previously, it was found that the Macoa civilization was preceded by another higher culture, that of the Arhuacos, who were far better workers in clay and stone than the cruder races which now live in the district.

Image Number: 42546

On the top of the “Pueblo Viejo” hill were found the ruins of an old Spanish building, consisting of about five rooms. The walls are not standing, but the boulders from which the walls were made are still seen in regular lines, denoting the limits of the building. From these remains, and from the quantities of Indian artifacts that were scattered on the site, one is allowed to deduct that in all probability here was found one of the ten Missions of the Capuchins of Navarra that were at one time established among the Motilones of the lowlands, of which Missions and their subsequent abandonment brief mention is found in some of the old historians. It becomes an interesting conjecture whether the good Capuchin Fathers were massacred by the Indians or whether they left their home voluntarily. We fear the former was the case.

After completing the survey of “Pueblo Viejo” and the surrounding country, our next problem was the transportation of the resulting specimens and of the specimens collected among the Macoas, to the port of Maracaibo. Thanks to the aid given by the Caribbean Petroleum Company, I managed to have boxes made at La Horqueta, and to arrange to have these boxes transported from La Horqueta, overland, to Iguana Point on Lake Maracaibo, and thence by sailing sloop to Maracaibo itself. It is frequently one of the great difficulties of a collector to arrange for the packing and transportation of his specimens in countries where facilities for transport are bad and where the necessary packing to place between the specimens is almost unobtainable. The help given me in La Horqueta and Maracaibo was therefore all the more valuable. When I state that the large box of ethnological specimens was about six feet long and two feet square and weighed three hundred and twenty-five pounds, it will be understood that the transportation of this on muleback would have been impossible and that the cart of the Caribbean Petroleum Company proved to be a godsend.

Image Number: 42545

I would like to give the reader some idea of the hardships of a journey of the kind one undertakes when exploring the Perijá region. I find in my diary the following dangers enumerated under the heading “diseases.” Amoebic dysentery, yaws, false yaws, loss of skin pigment, hookworm, malaria. Under the heading “insects” I find: scorpions, centipedes, ticks of all kinds, the large “mata-caballo” spider, literally the “kill-a-horse” spider, ants. When it is stated that there are many other insects that bite, and frequently produce painful ulcers, as I found to my cost, it can be understood that insect life in this region makes life unpleasant and at times unbearable. Furthermore there is a fly which has the unpleasant habit of depositing its eggs under one’s skin. The egg develops into a subcutaneous insect which makes the unfortunate recipient forget all other troubles. At times the ticks are so bad and in such large quantities that one is obliged to rub the entire body with tobacco leaves that have been soaked in water. This is the only efficacious means of getting rid of the pests before they become permanently attached to one’s skin. Under the heading of “dangerous animals” I find in my diary: snakes, tigers, and jaguars. The snakes of the Perijá district are of the most poisonous variety known and many deaths occur from their bites. Strange to say, the Macoa Indians claim immunity from snake bites. While among them I was shown a plant which they called “contrarépa” which they claimed was an absolute cure for snakebites. In case an Indian was bitten by a poisonous snake, an infusion of the seed pods and leaves was drunk and furthermore a poultice of the chewed seed pod was applied to the bite. I did not see the cure used for snakebite, but saw it applied to the neck of an infant that was bitten by a scorpion and noted that no subsequent swelling was apparent over the bite, nor did the child suffer from fever afterwards. In consequence, I imagine the “kontrarépa” contains some alkaloid which must prove decidedly efficacious for poisonous bites. I succeeded in obtaining about five hundred well dried seeds of the plant and an excellent photograph of the plant in flower. A mention of a similar plant can be found in an account written by the French explorer and geographer Elisée Reclus in 1861 when this scientist made a study of the tribes inhabiting the opposite, i.e., the western or Colombian slopes of the Sierra de Perijá. Reclus states on pages 215-216 of his book (“Voyage a la Sierra Nevada de Saint Marthe,” Paris, 1861), “The guao, a well-known plant, of which the sap, inoculated in advance, certainly preserves from death all who have been bitten by poisonous snakes. The country people [Reclus speaks of the inhabitants of the Colombian, i.e., the western slopes of the Sierra de Perijá] who desire immunity, inoculate their thumbs with a small part of the cellular tissue of the leaves of the guao and drink an infusion made from the small branches; they repeat this inoculation every fifteen days for some months and can then brave the dangers of vipers and coralsnakes with impunity. The guao is so named from a bird, commonly found in New Grenada which will, according to reports, in its fights against snakes, perch itself on this plant and fortify itself by hastily eating some of its leaves.” It is well possible that the “contrarépa” of the Macoas is the same as the guao of the neighboring Colombians, especially so, as the Macoas also told me of the snake fighting bird and its habit of eating of the “kontrarépa.” That the snakes of the Perijá district are especially friendly towards strangers can be understood when I state that on two separate occasions, while among the Indians, I found the small coralsnake curled up near my campfire, said snake having elected this spot to escape from the cold of the nights. Another time, when putting up for the night in Machiques, a snake was found under some rubbish in a corner of the hostelry.

Image Number: 27219

Still another danger of the Perijá region deserves mention. Numerous marshes are found in the lowlands between the slightly elevated ridges of the hills. In these marshes, quicksands are formed during the rainy season. The trails of the savannas have of a necessity frequently to lead through the marshes, and unless one is accompanied by a guide who is well acquainted with the region, there is an almost unavoidable possibility of riding into a quicksand, of which the treacherous danger is not easily recognized. Numerous animals are yearly lost in this manner, and cases are not infrequent where horsemen and their mounts have disappeared from view.

A list of equipment taken by this expedition may be of interest. The two principal items on this list were a Burroughs Wellcome and Company medicine case and a sense of humor. The first I find absolutely indispensable, and has been the means, on this as well as on many previous visits to the tropics, of curing not only my own ailments and those of my companions, but of promoting friendship with the Indians visited. These cases are compact, easy to carry, and the medicines they contain do not deteriorate in the tropics. The second item on my last, the sense of humor, has been the means of helping many a man over many rough spots and of making him forget his troubles. A tent I did not carry. When it was necessary to spend the night away from camp, a waterproof canvas campcloth, suspended between two trees, filled every need. I found canvas dunnage bags the best for the transportation of my baggage as these containers are waterproof, pliable, and can be tied in such a manner that insects cannot gain entrance. A rubber poncho is of course a prime necessity. So is a mosquito net and a small acytelene lamp. A tank and chemicals were carried to enable me to develop my negatives within six hours after these were taken. This simple rule, which should never be neglected, is responsible for good negatives, is the only way, in fact, by which good photographs can be made. Perhaps one of the most important secondary items of my equipment was a roll of thin copper wire. It is surprising how much one can do with this wire and how many repair jobs can be undertaken by these means. Of the guns, rifles and revolvers carried it is unnecessary to say much. Almost any kind of shotgun will give good results in the woods, where long-distance shots are unobtainable and where one has to stalk one’s prey and fire at it in the trees. Rifles are unnecessary to a poor shot, who had far better rely upon a good load of BB buckshot for large animals and then trust to luck. This also holds good for a revolver, which in our case was purely ornamental. A long-barreled revolver, of large caliber, will, however, make an effective club, when used in a reversed position. In conclusion, it may be stated that we depended largely upon the local supplies for foodstuffs, some compressed tea tablets and Horlick’s Malted Milk products being the only foodstuffs we imported. The latter proved to be of especial value, as their compact form made them easy to carry, and their concentrated nourishment a great boon when one suffers the pangs of hunger.

Image Number: 27217

There is always so much more one might like to say in a sketchy report of this kind. So many experiences, humorous and otherwise, have to remain unrelated and so many of them have been forgotten. All in all, despite the hardships of the trip, the expedition was enjoyable, probably because we felt a sense of achievement upon the completion of the work which was more than gratifying. But the burial cave still remains unvisited and beckons to future explorers anxious to solve the mysteries of that most mysterious mountain range, the Sierra de Perijá.

T. DE B.