The late Mrs. H. K. Jewett, of Pasadena, California, a daughter of George H. Stuart, of Philadelphia, was for many years before her death, which took place in 1917, an ardent collector of Indian basketry, beadwork, weavings and silverwork. An admirer of the arts and crafts of the American Indian, Mrs. Jewett assembled her collections with a discriminating consistency, applying to every article a strict test of artistic merit. This critical restraint that guided her choice in each instance makes itself known in the content of the collection, which is one of great excellence. It was Mrs. Jewett’s wish that her collection should go to her home city of Philadelphia, and she selected the University Museum to be its permanent custodian. After her death, her husband, Mr. Jewett, carrying out her wishes, presented the collection to the Museum, where it is now exhibited. It will be known permanently as The Patty Stuart Jewett Collection in honor of the lady who created it to illustrate the arts and crafts of the American Indian. It will appeal especially to artists and to students of design, but it illustrates also the wealth of Indian legend, folklore, symbolism and traditions that were crystallized in customs soon to be forgotten.

Museum Object Number: NA8265

Image Number: 14565

In numerical strength, if not in general interest, the baskets occupy the most prominent place in the collection. There are nearly two hundred specimens, representing the best productions of twenty-eight different tribes, extending from the extreme end of the Aleutian Islands along the Pacific coast to southern California and then east across New Mexico, Arizona and Texas to Louisiana. This area embraces practically all of the tribes producing artistic basketry.

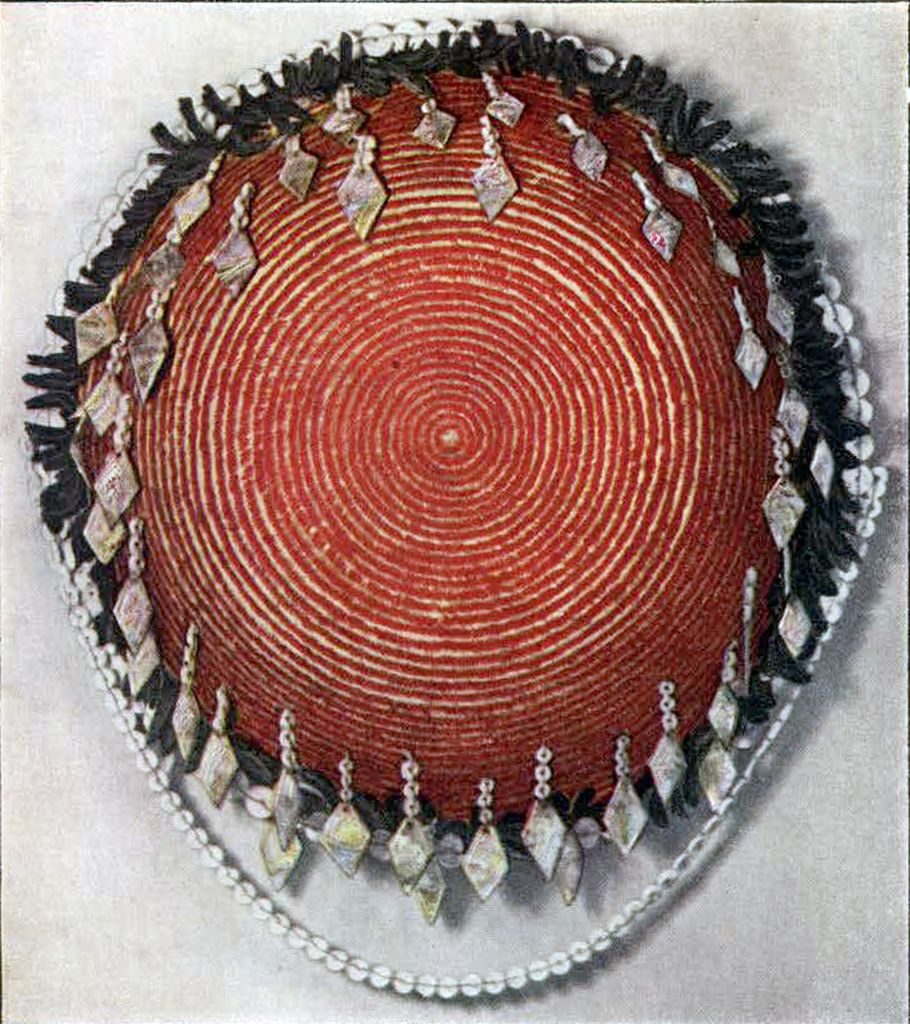

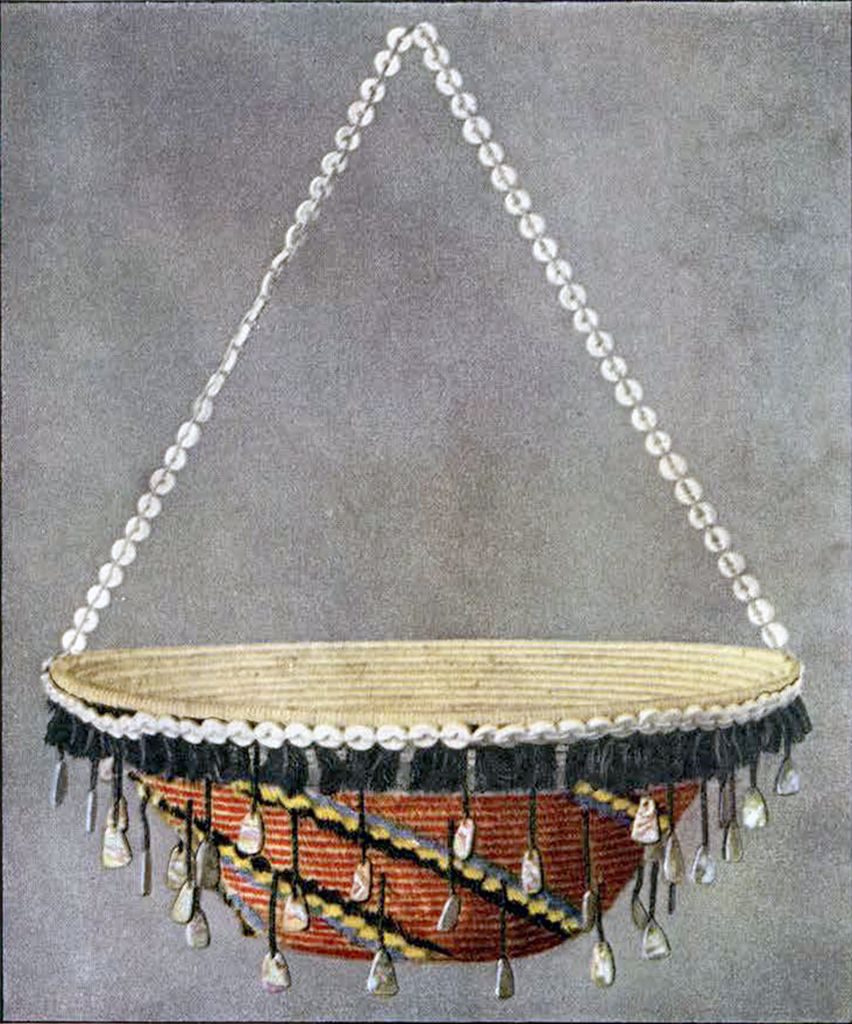

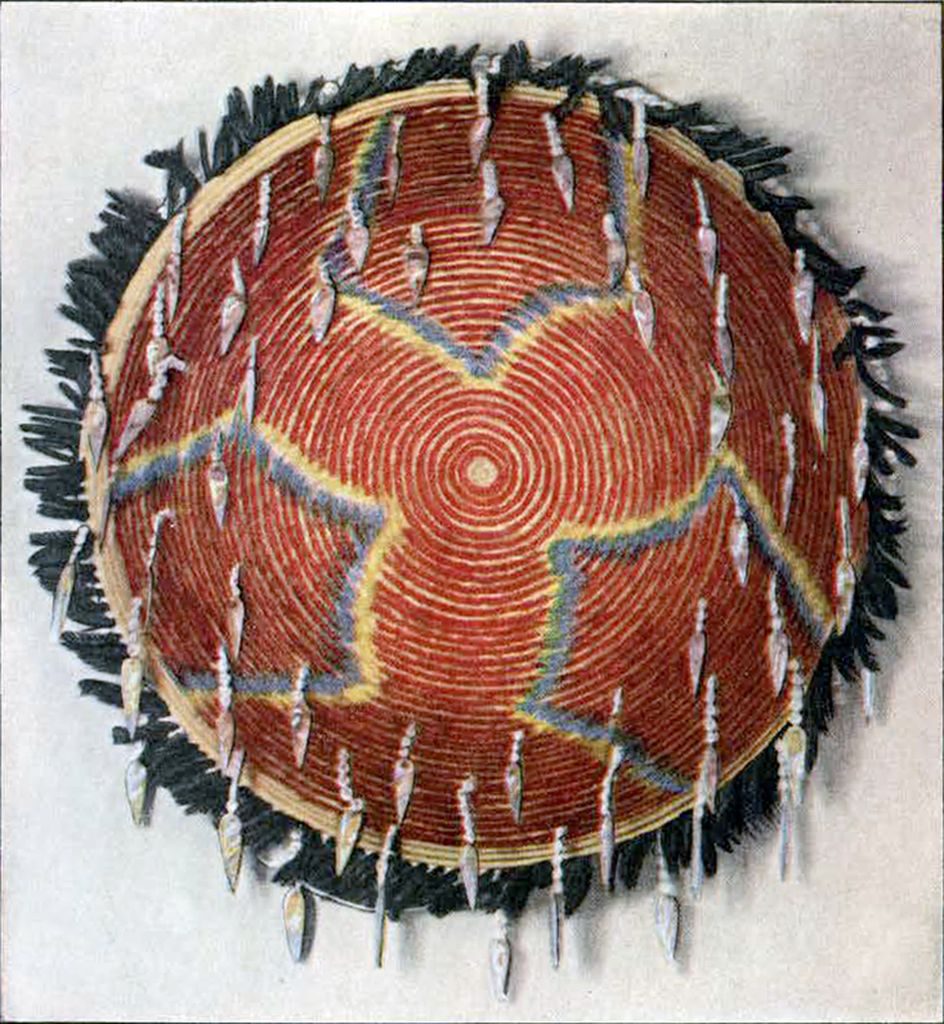

The most striking group of baskets was made by the Pomo Indians who live a short distance north of San Francisco. In this group of Porno basketry is found a variety of shapes, weaves, decorative motives and functions. One of these varieties is remarkable for the fact that each basket is covered on the outside by an elaborate and brilliant feather decoration, a distinctive characteristic confined almost entirely to the Porno and their immediate neighbors. Such skill has been attained in this method of beautifying that the feather covered surfaces have almost the smoothness of the breast of the bird itself. When one thinks of the time and patience required to assemble the feathers, sort them and finally work them into the structure of the basket in such exquisite and harmonious designs, one’s admiration for the work is combined with a great respect for the worker.

All of the colors used have a symbolic significance based upon the characteristics of the bird furnishing the feathers. The red feathers come from the crest of the woodpecker and denote bravery or pride. The yellow lark feathers signify gaiety, success or fidelity. The irridescent green of the mallard stands for watchfulness and discretion. The black quail plumes indicate conjugal love and beauty while the white wampum is symbolic of generosity and riches.

The baskets covered almost entirely with red feathers are known as sun baskets, for, according to tradition, it was a basket of this type in which the sun was stolen from the other world and brought to this. The baskets decorated with yellow feathers are called moon baskets.

Museum Object Number: NA8237

Image Number: 14559

In addition to feathers, clam shell beads and pendants of iridescent abalone shell are employed to embellish the basket. The shell beads are used as a border about the top and a few are strung to form handles for suspension.

Not only the feathers themselves but the designs in which they are wrought often carry some sentimental thought. This, combined with their exquisite fineness, makes the baskets very acceptable gifts among the Indians. Besides serving as gifts to show friendship they are also given to express sympathy.

After a death an excellent specimen might be presented to one of the bereaved, who, according to custom, was bound to burn it. Fortunately for this and other collections some of the mourners felt the call of mammon stronger than social convention and permitted many of the best examples of this art to pass into the hands of the white man.

Museum Object Number: NA8266

Image Number: 14567

A tiny and carefully constructed basket is a bowl-shaped one less than three thirty-seconds of an inch in diameter. Ten very fine stitches suffice to sew the uppermost coil. An attempt is made at ornamentation lower down by sewing with alternate stitches of black and white. This is one of the smallest examples of real good basketry that has ever been made. Other specimens are as small but are much cruder and do not combine extreme minuteness with fineness of sewing. This doubtless is the chef d’oeuvre of one of the best basket makers, who here simply outdid herself in producing an example of extreme smallness.

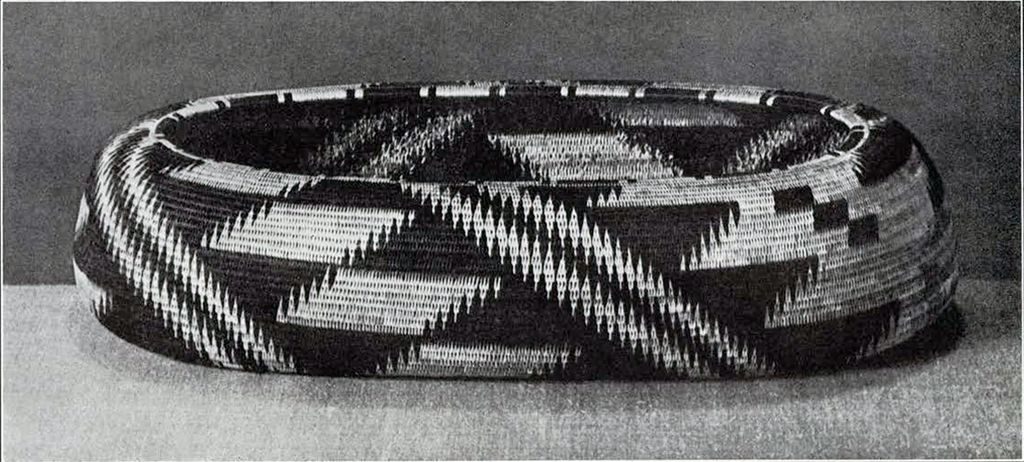

Other examples from the Porno Indians include a large oval or boat shaped ceremonial basket which served as a container for storing the medicine man’s ceremonial objects, and several smaller ones of similar form which served as gift baskets; and many bowls, trays, and carrying baskets.

Another phase of the Indians’ life in relation to basketry, is suggested by a large gambling tray from the Tulare of south central California. The tray is extremely large measuring thirty-one inches in diameter. It is decorated by two rows of dancing men separated by a band of rattlesnake design and surrounding a central ring of black diamonds. The colors are soft whites, reds and black. With this specimen are six dice made of half a walnut shell filled level with pitch and pounded charcoal in which are embedded several small pieces of bright iridescent abalone shell. The game is played exclusively by women four of whom take part while a fifth keeps the score with fifteen tally sticks. The game moves rapidly and the players soon get so excited that they gamble recklessly and seem totally unaware of the presence of others.

Museum Object Number: NA8246

Image Number: 14561

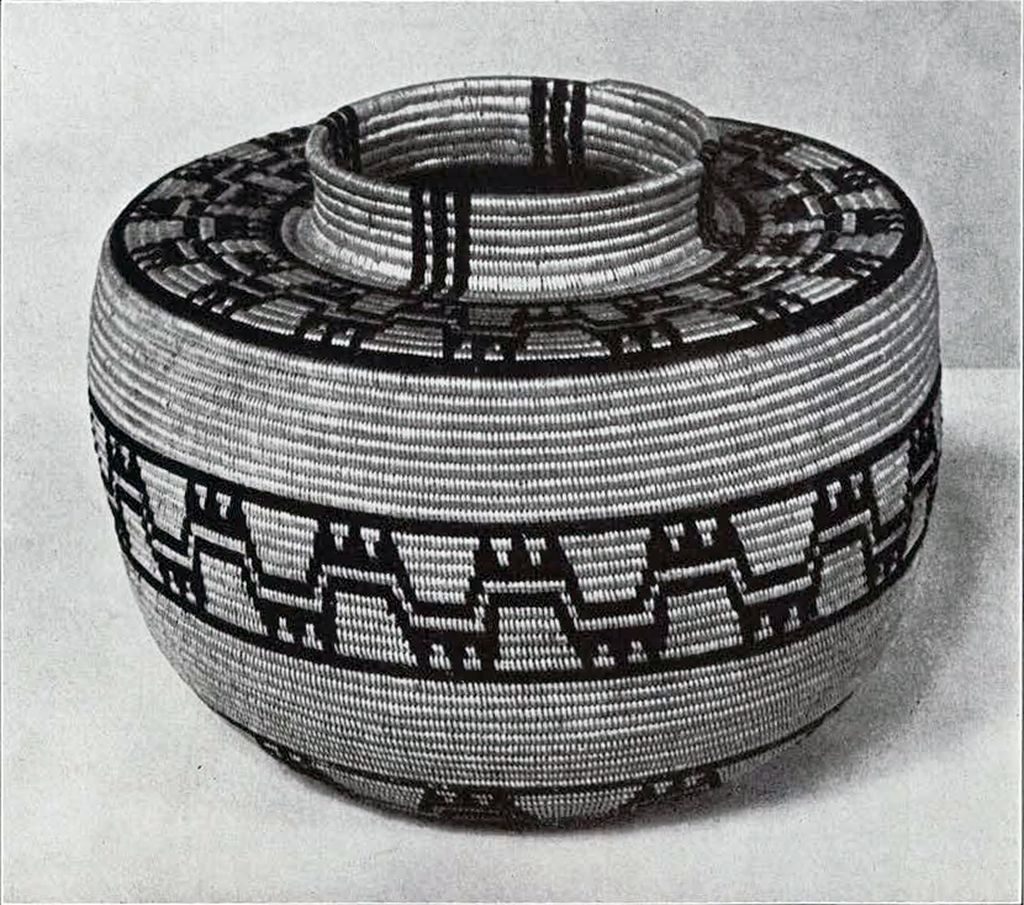

From this same section of central California are a number of examples of “bottle neck” baskets made by the Kern River Indians. Here, as elsewhere among the Indians, an elaborate and formalized symbolism had developed. One specimen that has taken its design from nature is decorated with three bands of crenellated ornaments in black. On the outer projection of each of the crenelles is a row of small triangles. This entire design symbolizes the spasmodic flight of the butterfly. Another specimen decorated with eight radial zigzags each composed of three lines is especially interesting on account of the evenness of stitching and a sort of clouded effect on the surface. This effect seems to have been intentionally produced by the selection and combination of splints which vary slightly in shade. The color of the whole is a rich dark brownish buff.

Museum Object Number: NA8267

Image Number: 14568

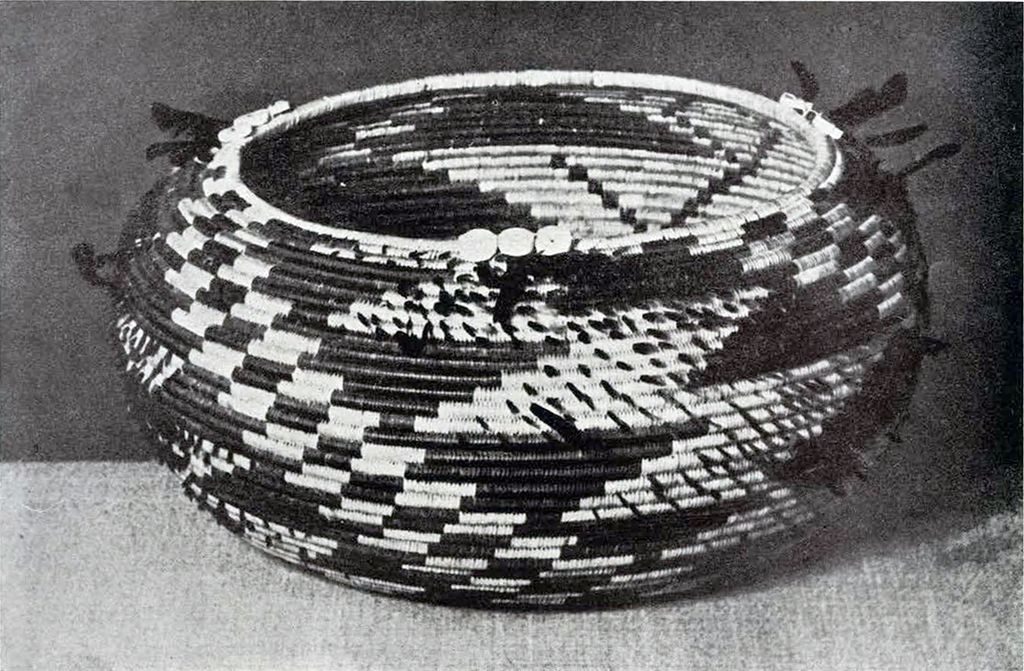

In addition to the Kern River Indians many of the surrounding natives make “bottle neck” baskets. The Panamints who live in Death Valley in southeastern California are especially good craftsmen. One example of their work shows many features common to the entire region. It has no bottom decoration but near the bottom is a broad band of very narrow diamonds doubtless modified from the prevailing rattlesnake design. Above this is a row of Greek crosses, and extending down from the outer edge is a serrated black border. On the top, surrounding the neck, is a row of men neatly worked in black. Four quail plumes spaced equidistantly about the mouth complete the decoration.

A bowl shaped basket about twelve inches in diameter is ornamented with six cycloidal radiæ made up of stepped rectangles, each of which encloses a diamond outlined in white. The radiæ are alternately red and black with diamonds of the opposing color. Similar diamond enclosing rectangles fill up the space between the radiæ at the basket’s edge.

All of the Panamint baskets are carefully made and the designs executed with a refinement and charm scarcely to be expected among the inhabitants of such a forsaken and desolate country. A great deal of time, care and skill are necessary throughout the process of manufacture from the securing and preparing of the raw material to the final completion of the basket. Willow shoots are cut and freed of bark and inequalities to be used as the foundation or coils proper. Other shoots are selected and the squaw bites one end in such a manner that it splits into three equal parts. With great skill, holding one part in her mouth and one in each hand, she splits the rod into three equal even splints. The same process is repeated with each of these, this time splitting off the pith with its adjacent brittle material and the outer bark. This produces a strong pliant strip for sewing. Ornamentation is produced by staining, by retaining part of the bark and by varying the stitch used.

Museum Object Number: NA8235

Image Number: 14558

Two specimens are especially worthy of notice not only on account of their beguiling mellow brown tones which attest to their great age, but also because of the fascinating associations which surround them. They come from the southern California Missions whose story is so closely interwoven with the romance and history of our Pacific coast. The ruins today are still the most picturesque landmarks of the region. The first to be established was in 1769 at San Diego. Here, and later elsewhere, the Indians were brought together and given religious and ordinary school instruction and also taught various trades. An almost ideal life was created for the Indian. There were short hours for work. Dancing and other amusements were encouraged and food was abundant. Oranges, olives, figs, bananas and grapes were cultivated about each mission while out on the plains vast herds of cattle and droves of sheep were ranged. But this easy existence did not last, for in 1833-34 decrees were passed to “secularize” the Missions and expel the missionaries.

This was followed by the almost complete and wanton destruction of the Missions. The orchards were cut down and the vast herds confiscated or stolen. Under these new conditions the Indians rapidly disappeared so that from a population of about 30,000 in 1834 there remain today less than 3,000.

The better of the two baskets was doubtless made while the Missions were in a flourishing condition. It is subspherical in form and about fourteen inches in diameter. The predominating color is gray but this is relieved by an encircling zigzag band composed of parallel strips of white, purple, black and brown. The latter color varies in shade from a rich, dark, reddish brown to a pale brownish gray.

Museum Object Number: NA8249

Image Number: 14560

The Karok Indians of northern California are represented by a pair of most graceful miniature storage baskets. Both specimens show the same beautiful workmanship and painstaking care in the selection of the materials. They are almost identically the same size and form, and even the lids with their graceful handles are very similar. The technic employed is twined weaving. Extremely slight hazel shoots are used for the spokes or warp and tough grass serves for the woof elements. Decoration is supplied by overlaying the woof with a strip of the black stalk of the maidenhair fern or with blades of bear grass that have been either bleached or stained. Some of this material has been dyed yellow and on account of the mordant used has become a beautiful though unusual lemon color. With this rich pale yellow as a background a series of interesting designs are worked out with the glossy black strips of the fern stalk. The elements of the serrated borders and of the zigzag band represent the “frog’s hand.”

Museum Object Number: NA8268

Image Number: 12751

The companion piece to this specimen has a background of black on which are several rows of superimposed isosceles triangles. These represent the head of the rattlesnake, and the design is locally known as “snake’s nose piled up.” Both specimens are decorated on the bottom and the handle of the lid.

In the manufacture of baskets of the fineness of the last two specimens even the weather must be studied carefully. No work could be done if the day were too dry or too windy, as the elements of the basket would dry too rapidly or unevenly and produce irregular places on the surface or even warp the basket out of shape.

Museum Object Number: NA8307A

Image Number: 12755, 12756

A group of several small trinket baskets from the Makah Indians of Washington and the ocean coast of Vancouver Island presents a method of weaving which seems peculiar to this tribe. The process known as wrapped twined weaving is a very simple one, so simple in fact that it seems little short of marvelous that it be confined to this small area. On account of the semblance to the old fashioned bird cage in which two main wires cross each other and are held at the intersection by a wrapping of finer wire it is sometimes called the “bird cage twine.”

A basket of this type is started as a mat of cedar bark strips each about a quarter of an inch in width. The strips are then split and turned upward and at an angle so that alternate ones bend to right and left. At the intersection of these warp elements a single ribbon of tough straw colored grass is wrapped. These wrappings are forced tightly home, and as they overlay each other with perfect regularity a very pleasing effect, not unlike a fine tiled roof, is produced.

By combining bituminous coal with chewed salmon eggs a black dye is produced which permits further embellishment of the container. On account of the weave these designs in black are almost entirely confined to rhomboids or combinations of rhomboids in crosses or the swastika.

In addition to the specimens mentioned there are many of almost equal artistic merit and interest. From the Island of Attu, the most distant of the Aleutian chain, is a cigar case delicately woven of fine grass. The Yakutat and Haida of southern Alaska and the adjacent coast and islands of British Columbia are represented by several rare old specimens. From the interior of British Columbia the Thompson River Indians have contributed imbricated baskets of great value and one of exceptional size. A group of characteristic soft baskets from the Skokomish Indians of Puget Sound shows the usual border of horses and wolves, distinguished only by the direction of their tails. Several interesting basketry hats and a dance basket or basketry wand from the Hupa might well be dwelt upon more in detail. Other excellent specimens come from the Maidu and Mono also of California.

Museum Object Number: NA8290

Image Number:12753, 14584

Many of the southwest interior tribes have contributed good examples of their handicraft. A well-made Navoho wedding basket, an olla and several trays from the Apache, who have been hostile almost the entire time since they were first met in the middle of the sixteenth century, are included. Several trays, some exceptionally well made and delicate, come from the Pima and a single very good specimen comes from the Havasupai. One exceptionally fine and old basketry bowl and two more modern pieces from the Chemehuevi represent a tribe whose old baskets are now almost unobtainable.

Closely related to the technic of basket making is the method of weaving shown in a Chilcat blanket in the collection. In part at least the same materials are used, for the woof elements are made of wool and cedar bark twisted together. As in basket making the preparation of the materials consumed as much time as the manufacture of the article itself. Six months was the average time required to make one of these beautiful ceremonial robes, so the ordinary weaver could barely produce one in a year. In this tribe weaving seems to be rapidly becoming an art of the past. In only a few families do the mothers teach and encourage the art. In former times weaving was confined to the higher classes who sometimes allowed the slaves to assist but never to go ahead with the work. The robes thus made were of such high value that only the extremely wealthy could afford them. For this reason it became an essential article of a chiefs dress upon particular state occasions. When a. chief died his robes were draped over and around him and were sometimes even committed to the flames of the funeral pyre, but were more often hung outside of the grave house in which the ashes were placed, and allowed to fall to pieces. Some robes were kept in the chieftain’s family and descended from one chief to another. These robes when not in use were kept in cedar chests, protected from moths and the elements. Thus they show no signs of decay or wear. Only the dyes used enable one to estimate their age.

Museum Object Number: NA8297

Image Number: 14589, 14590

The design is always animal in form and totemic in character. The example collected by Mrs. Jewett depicts a highly conventionalized whale diving. The blanket, while primarily serving as the means of exhibiting the clan totem, is very pleasing to the eye on account of its shape, elaboration of ornamentation and harmonious color effect. Designs of this character are painted by the men on a board which serves as a pattern for the women weavers.

The other tribe of noted blanket makers, the Navaho, differ in many ways from the Chilkat. They use no patterns but evolve the design as they weave. The best examples of Navaho weaving are in many ways like Oriental rugs. Subjection to hard usage brings out their particular beauty and softness.

According to tradition the early blankets were made of cedar bark and yucca fibers. Native cotton was doubtless used for many years before the Spaniards introduced sheep, which provided the Navoho with a new material for weaving. About 1700 the Spanish traders brought in a flannel or baize known as bayeté which the Indians would ravel out and retwist the thread for their finest blankets. Bayeté blankets were seldom used except on festal occasions, such as councils, dances, or races.

Museum Object Number: NA8279

Image Number: 14576

The Jewett collection is fortunate in possessing four of these rare bayeté blankets, one saddle blanket and three Honal-Kladi or chief’s blankets. It is a natural conjecture that blankets of this latter type are the first contribution to the artistic progress in design among the Navaho. In all probability after the single color blanket had been evolved and before any geometrical or symbolic design had been used, an attempt was made to beautify the robe of a chief so that it would differ from that worn by the ordinary man of the tribe. This change was made by introducing panels of different widths and colors and later by bringing in bands of color crossing these panels. Black, white, red, blue and rarely brown have been combined in a simple but very pleasing fashion on the three specimens. The saddle blanket is another delightful piece decorated with complicated geometric designs in soft old blues, reds, white and a greenish brown. The blues seem as bright as they ever were while the reds have been toned down to a soft delicate old rose. All of these bayeté blankets, and many of the others, are examples of the most excellent and skilful workmanship.

Other robes in the collection are made of native wool dyed with native dyes and a few are made of Germantown yarn. While these are not as eagerly sought for by collectors as those made of bayeté, they are characteristic specimens necessary to make a complete exhibit of Navaho weaving.

Museum Object Number: NA8289

Image Number: 14577

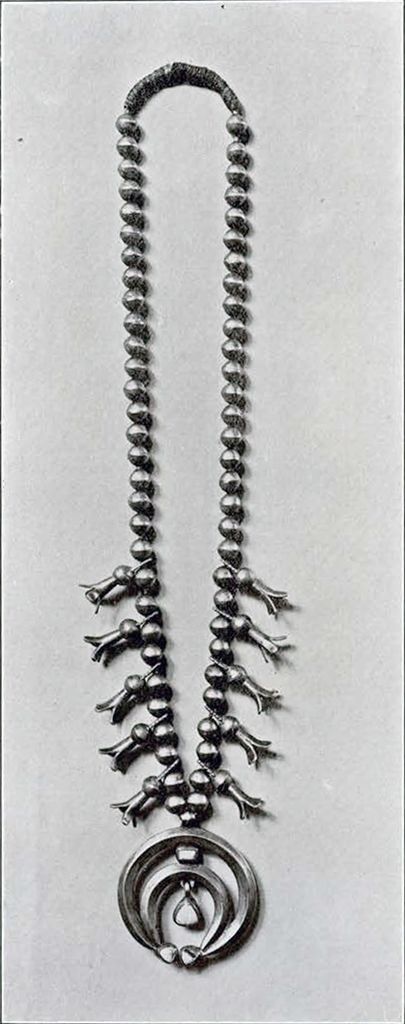

Nor are specimens from the Navaho lacking to show that the men were creators of objects having great artistic merit. While the women were the most expert Indian weavers, the men were the premier silversmiths. Equipped with the most simple and primitive appliances they were able to produce work comparable to the best of our jewelers. Two belts of silver plates, each plate carefully hammered into shape and having a handsome turquoise set in the center, are perhaps the most valuable. In addition to these there are arm bands, belt buckles and necklaces. Of the latter, some are made almost entirely of well wrought silver beads or pendants while others are beautifully made of turquoise and shell beads.

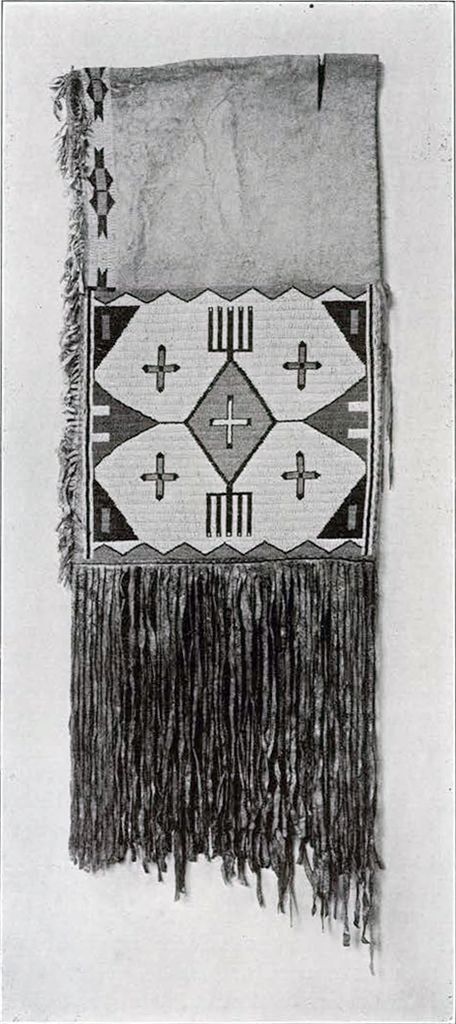

In this brief description of the Patty Stuart Jewett collection I have space merely to mention that, in addition to the things already described, there are included a large number of examples of beaded work, such as pipe bags, medicine pouches, clothing, horse trappings and knife sheaths, representative of many of the tribes of the Great Plains.

B.W.M.