A Guatemala Myth From Robert Burkitt

The Museum has recently recieved from Mr. Burkitt a myth of the Kekchi Indians written down in the Indian language under his personal supervision and afterwards translated by him with a set of notes to explain and elucidate the text. Mr. Burkitt’s intimate knowledge of the Kekchi language and his familiarity with the mental habits of the Indians makes his text a valuable contribution not only to the linguistics of Central America but to the native American folk lore and mythology as well. The text is accompanied by a preface and the whole document will be published in a seperate monograph in teh scientific series of the Museum. Meanwhile as the matter is one that will not fail to interest readers of the Journal, the translation is printed here together with a part of the preface and such notes as are essential to an understanding of the text.

The printing follows exactly Mr. Burkitt’s copy. We adhere to his spelling and manner of writing English in order to preserve the unique character of the document.

G. B. G.

A Legend Ov The Kekchi Indians:

the Indian Principaly By The Late Tiburtius Karl Ov Kobán Guatemala

Translated By R.B. For The University Museum 1918

Preface.

When you try to get hold ov a fairy tale in Indian, you find two principal difficulties. One ov them iz to get an Indian who can tel fairy tales: and the other iz to get the tale down on paper.—Many Indians, in my experience cant tel fairy tales. They dont know them: or if they do, they dont remember them. Most Indians hav heard fairy tales. They hav heard this or that tale—told by an old man at a feast, or sitting round the fire. And they remember something about it, perhaps: and they know it again when they hear it. But when you ask them to tel it, they ar very likely to be floord. That iz one difficulty.

And then comes the other, which iz more troublesome, When you do find a man who can tel a tale, you stil cant get the tale down on paper. You cant get it down az the man speaks. You couldnt get it down in English, az a man spoke—without short hand: much less in Indian. Ov course you might remember some ov the mans expressions: and in the end no Bout you could put something together that would be intelligible Indian: and might, in fact, be very good Indian :—but it would be your Indian. It might be az good as the real thing. It might be az good az Indians Indian. But it could not profess to be any thing but your Indian. You might az wel, I should supoze, rite the thing in English at once.

The Indian ov this little tale iz the real thing. The difficulties about getting Indians Indian wag got over, by having the tale ritten by Indians themselves.

Image Number: 15422

Ther ar not many, but ther ar Indians, here and there—mostly about the towns ov Kobán and Karchá—who can read and rite, in some fashion, in their own language. The riting thay can do, az you may supoze, iz not apt to be any thing real fine. The men ar more used to grasping a bush nife than a pen.—And besides, even to Indians themselves, riting in Indian iz not such plain sailing az you might think. The men hav learnd reading and riting, not in conexion with Indian, but az something that belongs to Spanish. In riting Indian, they hav no models. Each man spels, and divides hiz words, or joins them together, acording to hiz own notions. Each man iz hiz own stool master. An Indian riting Indian iz exploring hiz own language.

However, it iz hiz own language. And I thought that if any thing worth looking at, in Indian, waz to be got at all, it would hav to be through some ov thoze men. I made the experiment. It happend that two ov the men that I got hold ov, one ov them a Kobán man, and the other a Karchá man, each knew something ov this tale—it waz a tale I had heard something ov before—and I got each man to rite out for me what he new.

The two ritings when they were done, ov course wer not alike. And it turned out that the one ov the two men, the Kobán man, not only rote much better than the other, but new more ov the story.

At the same time that other man, who new less ov the story, new an interesting part ov it that the Kobán man didnt know. What I did then,—I had the Kobán man read the other mans story, and incorporate the other mans story with hiz own. Some paragrafs ov hiz own wer dropt, and new paragrafs wer added. At the same time the language ov the tale, throughout, waz closely revised.

Image Number: 15423.

Finally, az a check on slips ov the pen, or any other small faults, I had the revized tale ritten out afresh by a third man, who new nothing about the tale, but who had learnd reading and riting in my alfabet. The man found nothing ov the nature ov a mistake, whether in words or in pronuncuation: but he made some slight improvements ov fraze.

The rezult ov the process iz the tale as it now stands. You will find plenty ov faults ov composition in the tale. The telling iz uneven. Some points ar brought plainly before you, and others seem to be unduly slighted. You ar struck by abrupt transitions. Possibly ther ar points left out. And so on. But on the whole considering the riters, I think the tale iz not a bad job.

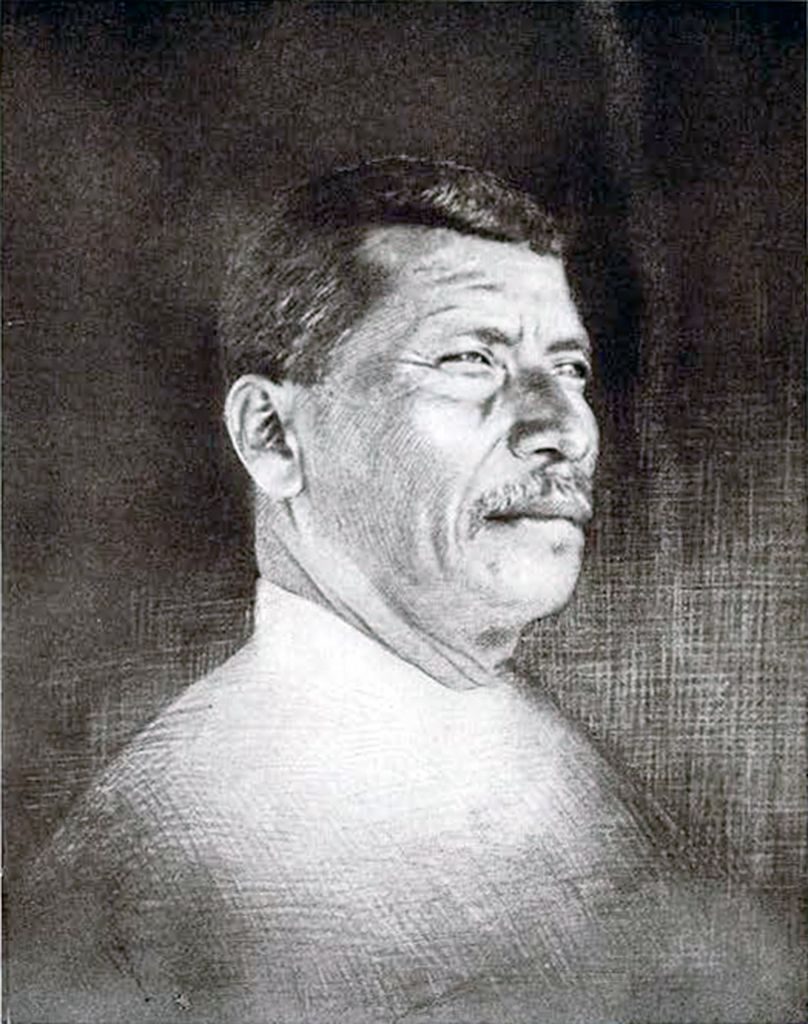

The Kobán man, who did virtualy all the riting ov the tale, waz a certain Tiburtius Kaál. He waz much the most competent man that could be found: and he iz now, I am sorry to say, dead.

I am able to prezent you with hiz picture. The man waz a pure Indian, with features az you can see, ov that somewhat Jewish cast, which is not altogether uncommon among theze Indians. Hiz hair waz still black, but he waz now a man ov over sixty. For a long time past, he had been one ov the chief men, in fact waz the chief man—the father ov the town, az they say—among Kobán Indians. He waz a man ov sharp wits—too sharp, his enemies said: and he waz that rara avis in terris, an Indian with what you might call a literary turn. Not only could he read and rite az wel az any body, but he made a hobby ov reading and riting in Indian. He had invented an alfabet for Indian. He rote, in the form of a speech, a life ov Saint Dominic, in Indian—Saint Dominic is the patron ov Kobán: and a life of Saint John Baptist, the patron ov an other Kekchi town: and other pieces.

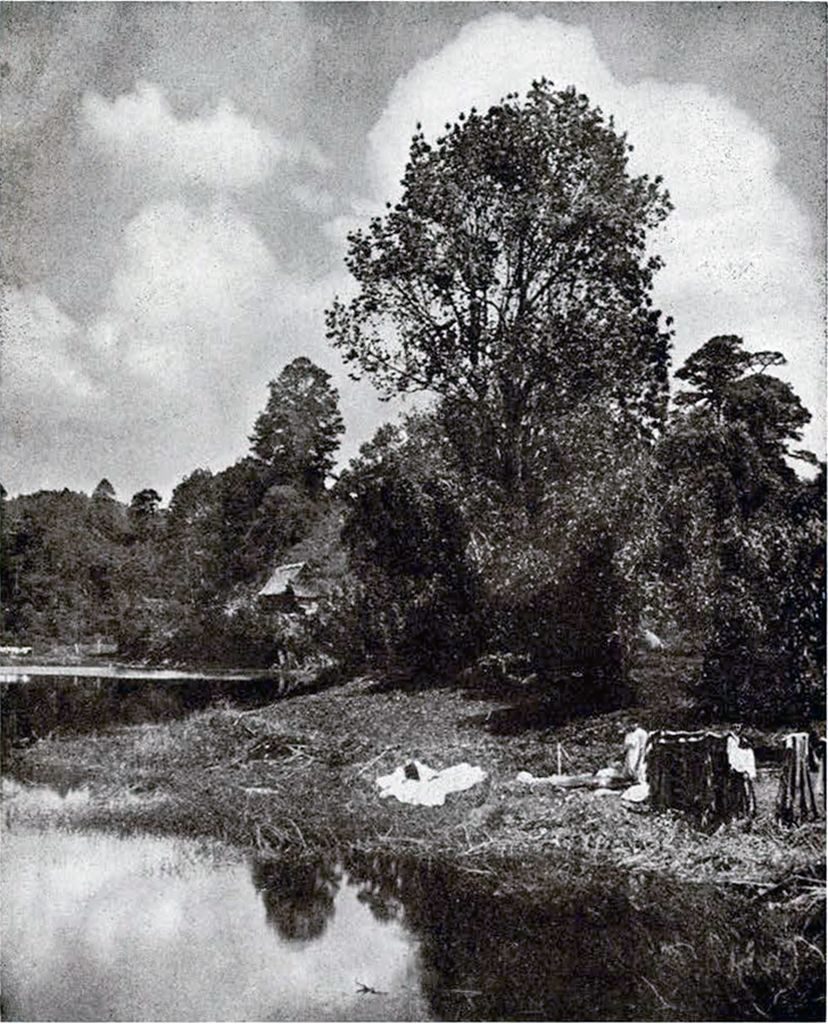

This fairy tale that I am sending you waz not the only thing ov the kind, that he waz to hay done for me: but it waz the only one that he finisht. He had a stroke ov palzy at the beginning ov the year, and he died in July.—This little picture iz a view at the foot ov the Calvary hil, in the town ov Kobán. The hil (which iz to the right) iz where Tiburtius iz buried.

Image Number: 15424.

Tiburtius belongd not to this present day ov progress (az it is calld) in Guatemala, but to a day a little before it: when the country waz stil out ov the world: when the land owners wer not yet planters: when the labour agent waz stil below the horizon: when the Indians life waz not yet made a burden to him: and Indian customs, and Indian learning—such az it waz—stil flourisht under the shadow ov the church. That day is gon. Whatever the prezent day may produce, it wil probably not produce an other Tiburtius Kaál.

To come back to the fairy tale—or to the tale: as ther ar no precise fairies in it—the tale is entitled by Tiburtius, a Thing that happened in ancient times, through the stealing ov Shukanéps dauter: but I supoze it might az wel be entitled The Hils and the Corn. The main buziness ov the tale iz that corn iz hidden and recovered. The persons ar hils and animals.

Quare populi meditati sent inania?—Thoze who make a science ov fairy tales, wil be able I supoze at once, to declare the interpretation ov the tale, and to indentify the tale with any one ov a dozen others. For my own part, I find the tale dul. And I supoze that the chief intrest ov the tale would lie, not in the tale itself, but in the fact ov its being prezented in authentic Indian. The tale would be interesting, I should supoze, not so much to thoze who for any reazon wer intrested in fairy tales, az to thoze who wer intrested in the Maya languages.

And that iz why it iz that I have made the translation the sort ov translation that it iz. You wil see at once that it iz not a free translation. It iz a translation meant to be ov use, especially, to readers who wish to follow the Indian. It iz meant to be az nearly az possible, a translation ov that slavish kind that school boys call a key.—I say az nearly az possible: becauz any thing like a word for word translation, from a Maya language into English, iz not az a rule possible. The two languages ar so differently put together, they step with such unequal steps, that any intelligible translation from one to the other iz bound to be a loose translation. But ther ar degrees ov looseness: and I hay taken pains to make the looseness a minimum.

R. B.

Things That Happened in Ancient Times Through the Stealing Ov Shukanéps1 Dauter.

Shukanép having rizen very early, saw that his dauter waz not in her sleeping place. He askt hiz servants whether they had seen her since her waking. The servants said that they had not. They made a complete search for her eery where, and not a bit did they find her. She waz no more there.

Exceedingly angry at the loss ov hiz dauter, Shukanép sent to call the worthy counselors, ov whom theze ar the names: mount Pansúh, mount Kekgwàh, mount Master2 Puklúm2, mount Chitsuhày, mount Chichén, mount Master Flint.3

Image Number: 15425.

And the counselors at once came. Shukanép went out to receiv them, with hiz heart upset, and aflicted in mind. He informed them that hiz cherisht dauter had disapeard, without hiz having a notion where she had gon. And that iz the reazon that I hav sent and calld you, he says, so that you may say what I ought to do.

Anser waz made by Master Puklúm, an old hil, wily: sick, dropsical, an old man, hiz back bent with age: one that waz wize from hiz birth.

He said to Shukanép: Comand to hav loost and led out two ov the fine dogs that you hav. Say to them that they ar to go to the place ov the neibour, who iz between the sun and the wind.4

If the dogs come back, your dauter iz not there:

If the dogs do not come, it iz a sign that there your dauter iz.

Shukanép advized again a second time with the other hils. Theze others unanimously aproved the thing that Master Puklúm said. Acordingly Shukanep calld hiz two dogs (not mere dogs, one waz a puma, and the other a leopard), and sent them to do az the dropsical old man previously said.

When theze dogs got to the hil they wer sent to, they did not start back til the second day. And on the second day, before Shukanép had rizen from hiz bed, the dogs wer already waiting for him.

Shukanep roze, and calld hiz two dogs, to ask what they had seen and where they had been The dogs said to him: Your dauter Basket grass5 we hav found sitting on the nees ov the hil. Thorn broom.6 We did not come at once, becauz the hole day we wer tied up by Thorn broom, and he did not let us loose til during the night: being afraid of your knowing where your dauter waz.

Shukanep when he fully understood how this waz, what did he do but send and gather together the hole ov hiz goods. He calld the sizzor tail,7 he calld the hawk: Go to the hil Sakléch.8 he says. Say to him, that I beg ov him, that he would receiv and put by, in one ov hiz stony repozitories, the hole ov my goods: the first and foremost being the corn seed.

Image Number: 15428.

All my creatures,9 he says, flying animals and thoz with four feet, which feed on that corn, let them be there loose at Sakléch’s, for the magnification ov hiz forest places, til such time az I send again and get them.

The hawk went, along with the sizzor tail, to tel their message. Sakléch anserd favourably. Whereupon Shukanép gatherd all hiz animals, so that between them all they should take to Sakléch’s the five kinds10 ov corn seed.11 They went, thoze many animals, they carried the five kinds ov corn seed, and Sakléch stored it.

Sakléch who waz the first suitor12 for Basket grass, dauter ov the great Shukanep willingly complied with what waz askt ov him. But he did not know that Basket grass waz stolen by the circumventer Thorn broom.

Shukanép having become tired ov waiting for hiz dauter, who did not come near him, sent hiz younger brother, little Shukanép, to get her. But Thorn broom waz unwilling to giv her. Little Shukanép seeing the pride ov Thorn broom, set hiz fierce dogs on him. The dogs obeyd, they bit Thorn broom all over: but neither for that did he let out Shukanéps dauter. Little Shukanép returnd, and told hiz elder brother.

Shukanep on hearing this, waz exceedingly angerd. He comanded Mother Abaás,13 a neibour ov Thorn brooms, whether by civil means, or by uncivil means, to go and get out hiz dauter.

And this wize old woman, the wife ov Master Puklúm, made her self ready, and threw her self with a rush on Thorn broom. And Thorn broom at once surenderd. Nothing else waz he able to say, excepting to beg ov the old woman that she her self would bring them in before the great hil Shukanép.

So the clever old woman did. And Shukanéps heart waz set at rest when he saw that hiz lost dauter came near to him. He forgave Thorn broom who stole her. He recognized him az a good son in law.

After that, Shukanep calld again the sizzor tail and the hawk. My anger against Thorn broom iz past, he says. Go to the hil Sakléch. Say to him, that by means of thoze same beasts ov mine, let him return the various looking sorts ov corn that wer given into hiz keeping.

The hawk and the sizzor tail went and did their errand. But the hil Sakléch waz confounded and said: What haz happend, that he says, My anger iz slackend against Thorn broom.

The hawk and the sizzor tail anserd: Sir, what haz happend, Basket grass waz stolen, and since that haz married the hil Thorn broom: and they are living with Master Shukanép.

0! how can it he that Thorn broom haz married my dear14 Basket grass? How haz Shukanép practist this deceit on me, and mean while I the first asker for hiz dauter? O! insufferable act! Nothing else does it need, but only a revenge.

Image Number: 15429.

Say to Shukanép that it iz very much better to die cut in pieces, than to deliver up what he put into my keeping. The corn that he put into my keeping, I will hide for ever. All hiz animals, let them die ov rage and famin. Never again shal he see with hiz eyes a single grain ov the corn.

The sizzor tail and the hawk came and gave their message to Shukanép. And Shukanép sent and calld the counselors that they should say what he might do.

On that same day ther began a great famin among all the beasts. Already they ar distrest by hunger, the peccary, the wood pig, the paca, and all their companions: they went to look for food, and they did not find it.

The only thing waz, they met with the fox. [At this point the narrative is concerned with the coarse manners and false character of the fox. The others suspect from his appearance and behaviour that he has been eating. They question the fox who answers sardonically. The passage is necessarily omitted from Burkitt’s translation.]

The questioners began to laugh. They propozed among themselves that they should secretly follow this liar, just to know what it waz that he ate.

And they saw that the fox went to the hil Sakléch, to the base ov the clif where there waz a nest ov leaf cutter ants. And the ants by scores, and by four hundreds wer coming out and going in at a crack in the clif. And thoze that came out, came out with loads of corn. They wer taking the corn to their nest.

There the fox seated himself, beside the ants path; and began to snatch away the corn from the carriers, that came out from the junction in the clif.

Image Number: 15427

There the others found him. Now we hav found you out, where it iz that you find your food, they said. They comprehended that nothing whatever waz the fox eating but the corn which the ants had gon and found, in the place where it was hidden by the hil Sakléch. Happy at what they had discovered, the animals went scampering to report it to Shukanép.

What did Shukanép do, but apoint three bachelor hils, Chits& waz their name, to torment the hil Saklech: the thing being that he wisht them to rend the stone repozitory where the corn waz shut up.

And the first young hil came, and he flashes hiz fire15 against the elif. He put hiz wits, he put hiz heart to it., he put out all hiz strength, in order to break the rock, and not a bit could he do it.

Again came the second bachelor hil: no more could he. Lastly came the third: and so again it happened to him. Not the least does the clif break for them. Although it waz a shame to them, they rezolvd to tel Shukanep that their strength waz not suficient. They related how many times they had tried, and how many arts they had employd.

Shukanép seeing that thoze that had been there wer not fit to face the hil Sakléch, determind to send Master Puklúm. He quickly explaind to him the nature of what he waz to do.

Az soon az the old man understood what waz impozed on him, he said: How shal it be possible that an old man like me, exceedingly sick az I am, dropsical, swollen in my face, swollen in my feet, shal possibly smite the strong hil Sakléch? If the three big youths hav not been able to do it, much less can a bent old man such az I.

However, to make an end ov it, only perhaps becauz I am poor, I wil try. If I die, why, dead I shal be.

Come with me, neibour Master Flint: let me borrow your sand stone, also your fire stone, to whet my ax with and to strike my fire. Beat some what loudly your great drum at my going out; so likewize do it again at the time ov my coming in.

Come here, you my wood pecker. Go and perch your self against the clif ov Sakléch. There you wil begin to tap at the clif with our beak, until you find a part that is hollow. That iz the direction in which the corn iz hidden. When you hear that, that haz the hollow sound, ther you wil take your stand, til I make ready my fire and my thunder.

When I come, fear nothing. Fly away head downwards. Do not fly away upwards, becauz so I might burn you.

The wood pecker went to the clif of Sakléch, and did all that had been told him. Having at length found the hollow stone ov the clif, there he remaind: then he opend hiz mouth and cried, so that the old hil might hear him.

Master Puklúm stird himself strongly. He flung himself forward with all hiz fury: his thunder flashed out against the hollow stone where the wood pecker stood, and the stone was shiverd to bits.

The stony store house being smasht, the corn of many colours came out ov it, like a spout ov water. The corn was spild on the ground.

Master Puklúm returnd, acompanied by the many animals carrying the corn. Shukanép awaited hiz animals at the main entrance that leads to hiz dwelling. And that entrance place iz calld the Wild mens16 cave. There the animals went in, there they left their loads in a magnificient room. And there remaind for ever the five kinds ov corn.

Master Shukanép waz glad, and so wer the counselors hils. They celebrated the entry ov the corn with an extremity ov loud rumblings and thunders, shafts ov lightning, and snake lightnings, that crust each other in the air.

Before the worthy counselors withdrew, Shukanéps gave corn seed to all ov them: so that it being scatterd over their woodlands, their animals should not be left without food.

And to the stout hearted wize old Master Puklúm, he offerd to giv every thing that he should wish: and he put into hiz charge the over sight and minding ov hiz animals that had come from Sakléch.

But the wood pecker, some thing happend to him. When Master Puklúm let loose hiz thunder, the wood pecker lost hiz head. In stead ov making off head downwards, az comanded to him beforehand, he made off in stead upwards. Hence he waz not able to save himself from the old mans bolt. The top of hiz head waz a little burnt by the lightning. And so it iz that the wood pecker haz ever remaind with the top ov hiz head red.

And here ends the record ov the ancient hils: Master Shukanep, Pansúh, Kekgáh, Master Puklúm, Mother Abaás, Thorn broom, Basket grass, Master Flint, Chitsuháy, Chichén, Little Shukanép, the first Chitsék, the second Chitsék, the third Chitsék; also the worthy stout Sakléch: who was left with soreness ov heart: with anger against Shukanép, together with hiz it doing dauter.

END.

1 Shukanép is a conspicious mountain to the south east ov Kobán. It iz the highest part ov the range ov mountains that separates Kobán country from the basin ov the Polochík, and is the highest mountain ov the Upper Verapás. All the mountains in the story, except one, belong to the Shukanep range.↩

2 Master, man. I say Master, only to avoid saying Mister. Man (which cannot be accented) ansers usualy, exactly to our Mister, and has no other meaning in the language. The title is ofen given to hits.↩

3 Flint, Tonic: the only one of these names that haz a clear meaning. Some ov the other names sugest meanings. For instance Punklúm might be fancied to mean Earth smasher. Punk means to Smash, in Kekchí; and in some Maya languages (though not in any neibouring Maya languages) Iúm means Earth.↩

4 between the sun and the wind. Tiburtius could not explain this, He told the tale az it was told to him. Most likely what the expression signifies is some point ov the compass, between the rising sun, and a wind blowing probably from the south. The neibour as you see later, is another hit; perhaps about south east ov Shukanep.↩

5 Basket grass, Suqnkím: the name ov a hil. The Karchá form ov the word iz sujnkím.↩

6 Thorn broom, Alix mes: an other hil, the hil the dogs were sent to, the neibour between the sun and the wind. I don’t know the plant, thorn broom, from which the hil iz calld: but més iz a tough weed used for brooms.↩

7 sizzor tail, xaalamjé, a bird like a sea gul: it comes about the beginning ov the rainy season.↩

8 Sákléch iz the one hil that does not belong to the Shukanép range. In stead of being south east from Kobán, Sákléch iz about north west: and far out ov sight. Sakléch is about two days north ov Chamá, on the way to the salt springs. The name Sakléch, like Shukanép, haz no meaning in Kekchí.↩

9 creatures, alnq: animals kept by man: pigs turkeys, and so on. The wild animals belong to the house hold ov the hil and he speaks ov them.↩

10 the five kinds, li onób paáy I dont know how many kinds ov corn ther may be. Each region, almost haz its own kind. But in the story no particular kind ar thought ov. The five iz merely a representativ number.↩

11 corn seed, xnan ixím: or Seed corn: literaly, Mother ov corn.↩

12 suitor, aj ntsaám: Asker. Asking for a girl haz its formalities, and iz usualy a protracted affair, not conducted by the suior himself. Hild further apart than Sákléch and Basket grass may yet be husband and wife. In the upper Verapás, near Kaabón, ther iz a mountain Itsám, which iz wife to Seven ears, a mountain away on the Pacific side ov the country. Mother Itsám, az they call her, used to eat people: and stopt eating them when her distant huzband scolded her.↩

13 Mother Abaás, xanán Abanás: an other hil ov the Shukanép range. Abaás iz the name ov a useful timber tree.↩

14 dear, raom: from ra, to Love. The expression sounds a little sloppy, and an Indian, in the circumstances, would hardly use it: but you must consider that it iz put in by the story

teller for the sake ov hiz hearers.↩

15 his fire, xxamlél: the fire that iz natural to him. Xamlél iz the asociative case ov xam, Fire; in Karelia, xáml. The fire natural to the hil iz lightning. Thunder and lightning ar made out to be very much things ov the hils. Thunder is the voice of the bile. The ecoing ov thunder among the hils is the speaking and ansering ov the hils. In an other version ov this same tale, the chief persons ov the tale ar not calld hils, they ar calld thunders. Instead ov the sick old hil, ther iz a sick old thunder: and the three bachelor hils ar three bachelor thunders.↩

16 Wild men, ntxolwinq. The syllable wing means Man. The ntxol haz no clear meaning. I say Wild man, for ntxolwinq, but the word Wild man does not express the hole idea. The hole idea is a confuzed idea. The Cholgwínks wer the former inhabitants ov the country. They built the stone ruins that the country iz sprinkled with. The Cholgwínks whistled and the stones came in place. The Cholgwínks wer magicians. At the same time they ar imagind az hardly human. When you show an Indian a caricature portrait, he will be likely to ask whether it iz a human being or a Cholgwínk. It iz supzed that Cholgwínks some where stil exist. They ar regarded az wild people.↩