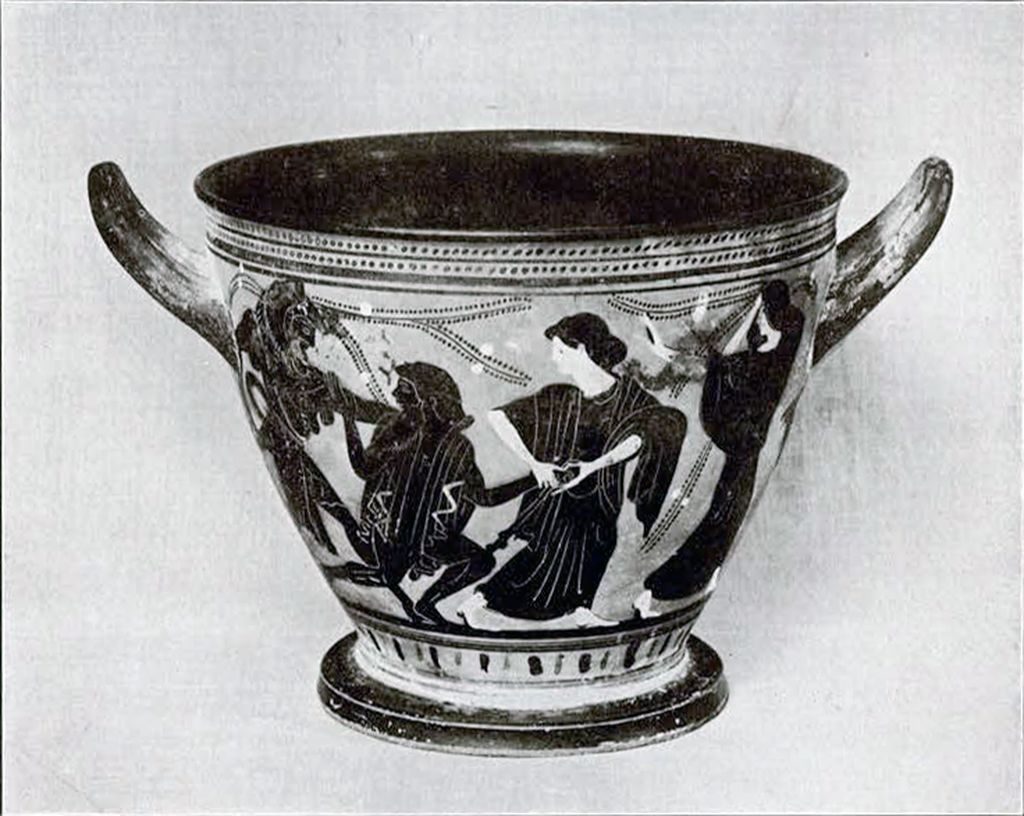

This vase was acquired by the University Museum early in 1918. Of its previous history nothing is known. Peculiar interest attaches to the skyphos for two reasons. First, the theme of the decoration, Heracles overpowering Nereus, is uncommon; second, the composition shows a decided variant on that usual in the black-figured technique. Let us consider the theme of the decoration first.

The obverse of the vase shows four figures. At the extreme left Heracles strides to right, with his left leg forward and only the toes of the right foot resting on the ground. Over a short tunic he wears the lion skin, the tail of which is looped up under his girdle. A baldric over his right shoulder carries a scabbard. With his left hand he holds Nereus by the back of the neck; and his right hand is drawn far back, swinging a battle axe. This weapon is rarely used by Heracles, and when found on vases is generally carried by figures of non-Hellenic race, wearing Thracian, Phrygian or Amazonian dress. Nereus sinks to his knees, his right hand outstretched toward his enemy’s chin in supplication. He is bearded and nude, save for the short cloak over his shoulders. His left hand which grasps a sceptre is tightly held in the hands of a Nereid, who is trying to drag him away from danger. At the extreme right stands a second Nereid, pausing in flight to make a gesture of supplication and despair. Each of these women wears a long Ionic chiton and a himation.

The reverse shows three figures. In the centre is Iolaos, to right, bearded, with a fillet in his hair. Like Nereus, he wears only a short cloak over his shoulders. In his right hand he carries a long knobby club, and in his extended left hand a bow and arrows. Before him stands Athena, watching the contest. She wears a long Ionic chiton and a himation, and has a high crested helmet on her head. Her left hand is lifted and rests on a slender spear. In her right hand, against her breast, rests a rounded object, possibly one of the golden apples, the prize of victory. Before her rises the trunk of a tree whose slender branches are spread over both obverse and reverse. This tree may be the one that bore the golden apples, for in its branches are round white objects which might be fruit. Behind Iolaos is the figure of Hermes advancing to right, but looking back to left. He wears a short chiton and himation, winged boots and a peaked cap with wings. His left hand is raised in a gesture of astonishment; his right arm is bent sharply at the elbow, and the hand holds a long slender wand. Behind Hermes, and under the handle is a large black ram, the attribute of the god.

Under the other handle is hung the quiver of Heracles, beside which rests his bow.

Museum Object Number: MS5481

Image Number: 2804

White is used for the flesh of women, and to pick out details such as the teeth of the lion, the crown of Hermes’ cap, and the tip of Heracles’ scabbard. Purple is used for the fillets, the beards, (except that of Nereus, which is incised), the lining of the quiver, the belt of Heracles and the object in Athena’s right hand. Incision is amply but carelessly employed:—lines of drapery pass through the white arms of the women, and although an incised line mark an outline, the paint is sometimes spread beyond it, as on the neck of the first Nereid. The eyes of the women are oval and a little open at the inner corner; those of Iolaos and Heracles are round; those of Nereus and Hermes oval and closed. The ears are poorly drawn and generally too high; the gestures awkward, but not crude. In general, defects are due less to the painter’s inability than to his indifference.

That the exploits of Heracles offer to the Attic vase painter an inexhaustible well of inspiration is almost a truism, but the story suggested by this skyphos is rarely utilized. Briefly, it is this: while Heracles was wandering in search of the golden apples DI the Hesperides, he came to the Eridanos. There the nymphs, daughters of Zeus and Themis, told him that only Nereus knew the way to the desired fruit. Heracles came upon Nereus asleep, and, despite the many metamorphoses of the old man, succeeded in wringing from him the secret.

Generally when Nereus appears on vases, he is a secondary figure. Sometimes he looks on while Heracles overpowers Triton or Kyknos; again, he sits apart from the action while word is brought to him of the rape of Thetis. Very rarely is he represented as important enough to warrant his being the centre of interest. This subordination is doubtless due to his being an insignificant figure in Greek mythology. His name is known chiefly from his daughters the Nereids of whom Thetis is the most important. Thetis in the Iliad speaks of her father as `’Aλιος γερων, a title which we know from other sources he shares with Glaukos, Phorkys, Proteus, the abstractions of the sea that preceded the Olympian god Poseidon. Like Poseidon Nereus displays the trident and fish as attributes, but more frequently he has a sceptre, as on the vase under discussion.

We have, then, in this skyphos a valuable addition to the meagre list of seven vases in European museums dealing with the subject of Heracles and Nereus.

Museum Object Number: MS5481

Image Number: 2807

The second point of interest is the composition. The tree beside Athena spreads its branches over both obverse and reverse, and binds them together. Furthermore, the three figures on the reverse do not really form a group, for Athena and Hermes draw attention not to the figure of Iolaos which they flank, but to the scene on the obverse of the vase. That the decoration is considered as a whole is further indicated by the fact that one of the handles rises directly from the right arm of Heracles. If the figures are projected as a continuous frieze, with the contestants as the centre of interest, it will be seen that the secondary figures are of two sorts. To the left stand three interested but aloof spectators, to the right two deeply affected. This arrangement is something more than the archaic schema of a central motive flanked by exactly corresponding figures. There is an effort for more complex composition, an effort no less commendable because not successful. The static figures at the left, interested in the action but taking no part therein are like a pre-Euripidean chorus. The two figures at the right, arrested on the point of flight, are to be messengers of woe. In other words, we have here in black-figured technique an example of what Gardner calls dramatic composition—the melding of all the decoration into a whole by making the subordinate figures into messengers and chorus.

The classic example of this sort of treatment is the Hieron vase showing the Rape of Thetis, where on the obverse the frightened Nereids flee to right and left from the intruder, and on the reverse, run as messengers to their father. The painter of this skyphos has not learned the perfection of rhythmic composition, which is an accomplishment of the advanced fifth century, but he has the glimmer of a great idea, and he is not afraid of experiment.

There is little opportunity to work out the personality of the painter, but certain characteristics of his may be noted. Although he works in the black-figured technique, he is not a primitive. His outlines are sure, and his errors are due to carelessness rather than to ignorance. He uses very little purple, and treats his drapery in the simplest fashion, incising with oblique and broken lines. Although he keeps the convention of a body full front with head and legs in profile, the effect is generally archaistic rather than archaic. The figure of Athena is in three quarter view, and only the Nereid at the extreme right displays the gaucherie of a misunderstood pose. The overlapping of the legs of Heracles and Nereus is scarcely to be found before the time of Euphronios who seems to have introduced this manner of indicating strain. Accordingly, the vase must be a product of the late black-figured style. Besides, two points should be noted:-

- Before and behind Athena are meaningless letters.

- The tail of the lion skin is looped up through the belt of Heracles.

These two points, taken in conjunction with the uncommon theme, and the unusual method of composition suggest analogies with the nameless master sketched by Dr. Luce as the painter of vases in New York and Paris, a contemporary of Nicosthenes. There is nothing to show that this skyphos is by his hand, but it doubtless dates from that same period, when the black-figured technique still survived side by side with the more popular red-figured ware.

E.F.R.