Neville’s Court

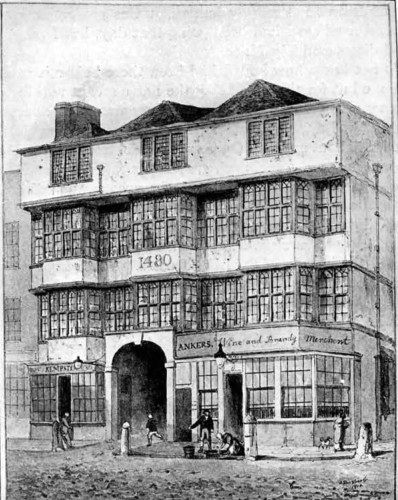

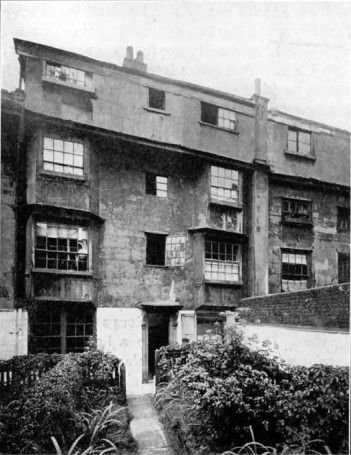

I find it more pleasant to call attention to some old houses that still survive and I have in mind a group in Neville’s Court, Fetter Lane. This narrow thoroughfare lies just outside the burnt area of the Great Fire and Neville’s Court is a short passage leading from its east side. The house at number 10 seems to be no older than the seventeenth century but numbers 13, 14 and 15 are about a century older. Each of these little houses has its garden, and the group, nestling near the heart of the City, affords a very good idea of what London domestic architecture was like in the smaller houses before the great fire of 1666. How much longer they will escape destruction I cannot say, but when I think that the old houses, inns and churches that have been swept away in the last fifty years would make a fine City, I have no reason to suppose that Neville’s Court will long survive. It is not my purpose to continue with a list of old buildings that are threatened with destruction; there are still enough to fill many pages of description, but those in Neville’s Court will serve my sole purpose which is to introduce the reader to a sample of old London houses in one of the few quarters that survived the Great Fire.

Ely Place

There are some spots in London in which I have a special claim because they are identified with my personal adventures. They are defined in my consciousness, not so much as parts of London as parts of my individual life and experience. Or perhaps I ought to say that I think of myself as an essential part of each of them. It amounts to the same thing after all for the condition of ownership is mutual. I own my farm no more than my farm owns me. In regard to these favoured spots in London, the sense of ownership rests on discovery. That is the best way to know places. The place to which you are guided through human aid and intervention will try to elude you after you have been introduced to it; but the place to which you are guided by an uncatalogued impulse, blindly—by accident if you like, promptly adopts you. It somehow gives you the impression that it has waited through the centuries for your coming. Your discovery, far from being due to blundering accident, records itself in your mind as a distinct achievement, highly gratifying to your pride and self esteem.

It was in this way that I found Ely Place, of which at the time of the discovery I had never heard. I had come out of Gray’s Inn through a narrow archway into Holborn and turned East towards the City. It was my intention to follow Holborn Viaduct into New-gate, but about Holborn Circus I went astray and turned into Charterhouse Street. On my left opened what looked like a short street with no thoroughfare, for it appeared to be closed at the farther end by a row of eighteenth century brick houses corresponding to the adjoining row on either side. The entrance from Charterhouse Street had an iron gate that stood open. Inside was a brick lodge. The form and proportions of the Place were those of a deep and ample courtyard and there was not a living thing in sight for it seemed as deserted as the Court of Baalbek. It was quite impossible to go by; to turn aside was not merely human, it was predestination. I do not remember where I had been going that day, but I never arrived for I had discovered Ely Place.

I do not know how long I had been there before it revealed its name to me but for the time being the name meant nothing. What did I know of the Bishops of Ely and how was I to remember that Richard III had a taste for strawberries? I was too much absorbed to be curious about names. On the west side, imbedded in the brick-built fronts, was a stone chapel, gray and weatherworn with a small retired entrance. Wandering through the swept and garnished chapel where candles were burning at the altar, through the dim mediaeval aisles and down into the crypt furnished for another chapel where more candles were burning, I lingered on amid the thirteenth century shades and the incense of St. Etheldreda’s. Emerging again on the pavements overlooked by lawyers’ offices, I found my way into a narrow cleftlike passage near the chapel and dined in the dim upper room of the Mitre Tavern where the mutton was good and the potatoes were good and the ale was good. And when I went home, all that I knew of the history of Ely Place was what was told me by the handsome and engaging girl that waited on me at the Sign of the Mitre which, carved over the door, seemed to confirm her story that some part of that deeply hidden tavern ensconced in London’s heart is a surviving relic of the town house of the Bishops of Ely.

Now it so happened that on the same day I had lunched early and well at Crosby Hall in Bishopsgate, for old Crosby Hall was in use as a restaurant at the time of which I write. In consequence I had stopped afterwards at a second hand book store in Charing Cross Road to get a copy of Richard III to recall the connection between that play and Crosby Hall. I did not know that the same play would take me back to Ely Place. That night in my rooms in St. James’s Place I came upon these lines in King Richard III.

Duke of Gloucester— My Lord of Ely, when I was last in Holborn I saw good strawberries in your garden there. I do beseech you send for some of them.

Bishop of Ely— Marry, I will my Lord, with all my heart.

I had seen no strawberries in Ely Place—nothing nearer than the two cheeks of the pretty serving maid in the Mitre who told me that the narrow passage by which I had reached the Inn opened at the other end on a street called Hatton Gardens, formerly the gardens belonging to Ely Place when the Bishops of Ely lived there, but now the quarter of the diamond merchants. That was where Richard saw the strawberries.

If you will walk through Holborn Circus toward Ely Place on any night after ten o’clock, you will find the gates closed and if you will observe the little lodge within at the stroke of the hour you will see a strange performance for a twentieth century setting. A Person —apparently a very important Person—emerges from the lodge door. He is dressed in a mediaeval fashion with a gold laced hat and he carries a lantern in his hand. Proceeding to the upper end of Ely Place and returning on the opposite side he calls out at intervals according to the hour and the weather. “Past twelve o’clock and raining hard—All’s well ” or ” Past two o’clock and a clear frosty night–All’s well.” He has been doing that regularly at every hour of every night for 632 years.

Whoever asks why this ancient watch is kept asks a very foolish question. It is a risky thing to give up any right or privilege that may belong to you, no matter how useless or obsolete it may appear. You never can tell at what moment it may become of immense importance.

The Northwestern boundary of the City OF LONDON runs just outside the gate of Ely Place which is thus imbedded in the heart of the Metropolis hard against that Stronghold of Power and Privilege over which the Lord Mayor presides. But the Lord Mayor and Corporation of London have no jurisdiction over Ely Place. The City police at their posts of duty look through the gates but they have no authority within and the London police do not intrude where their duties do not call them. The Metropolitan police likewise, who rule and represent law and order on the other side of Ely Place, have no power whatever within its territory. It is exempt from external authority. If you ask how this right was acquired, I confess that I do not know. The explanation is lburied somewhere in the history of Ely Place but it would probably require a mining operation to get it out. A more practical question that concerns you personally is what would happen if you should pick a pocket in Ely Place. I do not know for certain but I think you would be offered Benefit of Clergy which means that you would certainly be hanged. (See page 303.)

This is the history of Ely Place as I have pieced it together from various sources. In 1320 John Kirkeby, Bishop of Ely, bequeathed to the See his house in Holborn. His successor, William de Luda, built the chapel dedicated to St. Etheldreda. Another Bishop added a vineyard, a kitchen garden and an orchard. Thomas de Arundal in the later half of the 14th century built a great gatehouse or frontage towards Holborn. John of Gaunt, brother of the Black Prince, was living in Ely Place towards the end of the 14th century as the guest of the Bishop of Ely, after the burning of his own Palace of the Savoy in the Strand. He died there in 1399. During the troubled times following the death of Henry VIII when Somerset was Protector, Ely Place was the scene of plots and intrigues led by Warwick. In Elizabeth’s reign, it became the residence of Christopher Hatton, a favourite of the Queen, afterwards her Chancellor. On behalf of this Discovery of hers, whom she first met when she danced with him at a revel in the Temple, Elizabeth persuaded the Bishop of Ely to relinquish his town house, and it is said that the form of persuasion used was pretty high handed. Hatton thus obtained a lease of Ely Place for a period of 21 years for a rent of a red rose, ten loads of hay and £10, the Bishop reserving the right to walk in the garden and to gather therefrom twenty bushels of roses annually. Strawberries are not mentioned in the lease but there is no doubt that Ely Place gardens were famous for both strawberries and roses. Hatton built himself a mansion within these gardens and there, when he was sick, the Queen visited him daily, and when she had made him Lord Chancellor he proceeded in great State from Ely Place to Westminster. The Bishops of Ely never recovered full title to their property. Before the lease expired there was a special grant of the Crown confirming Hatton and his heirs in the ownership of the Estate. After his death it was occupied by his nephew and heir, another Christopher Hatton, whose wife played a rather conspicuous part in later years as the second wife of the great lawyer, Sir Edward Coke.

Bacon and Coke were rival suitors of the young widow and the lady’s choice fell on the lawyer and I think it served him right, for she made his life a burden. She was a Cecil and a Devil and proud on both accounts. She had reason enough to be proud, for that family—I mean the Cecils, not the Devils—has I suppose produced as much greatness as any family in the world and in the person of Lady Hatton it concentrated its great energies in the production of a piece of feminine perversity that would make the most conspicuous examples of today look pale and vapid. She stripped her husband’s rooms in Ely House of all their furnishings and made them uninhabitable. When she entertained King James, her husband was not of the company, and finally she denied him access to the house altogether. When he tried to arrange a marriage between his daughter and Sir John Villiers, brother of the Duke of Buckingham, his wife stole the girl away and hid her. Coke applied to the Privy Council for a warrant of recovery. This being refused by Bacon, he discovered the girl’s hiding place and took her away by force without a warrant. Then his wife applied in turn for a warrant that was granted at once by Bacon who supported his former attachment and opposed his old rival, so the girl passed again into the custody of Lady Coke. It is hard to withhold sympathy from a man in such domestic affliction, but remembering the way that Sir Edward Coke conducted the trial of Raleigh, I can only say it served him right.

When Gondomar, the Spanish Ambassador, arrived in England, the Crown, still exercising some measure of control over Ely Place assigned him Ely House as his residence. This brought him into rather close relations with Lady Coke who was living in the adjoining Mansion in Hatton Gardens—Hatton House. She and Gondomar soon quarreled and their encounters threatened to become an international incident. To annoy the Ambassador the lady closed her garden gate so that he was unable to go in or out privately as he wished to do but must use the front door where he was subjected to well planned annoyances. Their classic quarrels are among the legends of Ely Place.

The next tenant of Ely House +as the Duke of Richmond who received it of the Crown. The Duke died soon after the occupation and for a period the two houses of Ely Place—Ely House and Hatton House—plotted against each other under the generalship of their respective occupants, Lady Coke and the Duchess of Richmond. To get rid of her rival the Duchess made an offer to buy Hatton House. Its occupant seemed to favour the proposal and named a price carefully calculated at a ruinous figure. The Duchess agreed to the price and a contract was drawn up. The contention however was only intensified and when Lady Coke one day complained of the terms of the contract, the Duchess promptly took her at her word and left the house on her hands.

The Duchess of Richmond continued to live in great magnificence at Ely Place beside her rival. A contemporary gives the following description of the Duchess going to Ely Chapel.

She went to her Chapel at Ely House with her four principal officers marching before her in velvet gowns, with white staves, three gentlemen ushers, and two ladies to bear her train, the Countesses of Bedford and Montgomery, and other ladies following in couples, etc.; but all this does not bring down the pride of Lady Hatton [Lady Coke), who contests much with her about their bargains and the house.

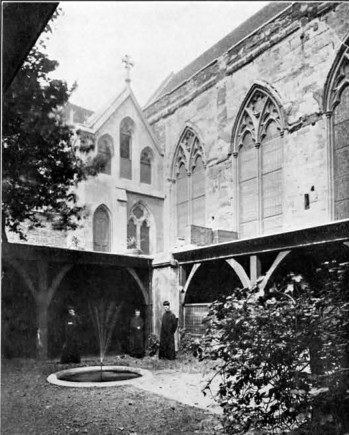

In 1762 the last Lord Hatton died and the rights that the family had held in Ely Place for nearly two hundred years reverted to the Crown. The Bishops of Ely however still retained some claim which they surrendered in 1772 in exchange for a house in Dover Street, now the Albemarle Club. Two years later the two famous houses were taken down and nothing remained but the old Chapel of St. Ethel-dreda. After lying unoccupied for a long time the Chapel was used by the Welsh Episcopalians till 1871. In 1874 it was sold by auction for £5250 and bought by the Lazarist Fathers. It has since been restored to its former condition, many of the wealthy families of England contributing. The large East and West windows were put into their present state of repair by the Duke of Norfolk and these windows are the most striking features of the interior of one of the most beautiful and enchanting chapels to be seen anywhere. Built in the last years of the 13th century or the first years of the 14th, having escaped the dangers of the Dissolution and survived the Great Fire, the Chapel of St. Etheldreda is today the only pre-Reformation chapel in England, so I am told, that belongs to the Roman Catholics.

Curran, the Irish patriot, lived in a house on one side of Ely Place. Opposite was a small piece of blank wall. Curran’s brother, with whom he had a feud, erected against that wall a little booth and hung out a cobbler’s sign with the family name conspicuously painted. There he sat and mended shoes and when he was not at home he hung a sign on the door—” Inquire at the house opposite.” I think this must be an incident that Stevenson makes use of in The Master of Ballantrae though he lays the scene in New York.