The Naas River

From the last week in the month of August, 1918, to the last week of October of the same year, a brief investigation was carried on by me among the Tsimshian Indians in Northern British Columbia. Most of this time was devoted to the Indian towns on both the Naas and the Skeena Rivers.

The Indian towns visited on these two rivers include Port Simpson, Kincolith and Port Essington on the coast; Greenville, Aiyansh and Git-lakdamix on the Naas; and on the Skeena, Git-sumkelum, Git-selas (an abandoned town), Usk, Git-wanga, Git-wan-lcool, Git-dze-gukla, Git-enmaksh, Hegul-git and Kisbayeksh. With few exceptions the towns mentioned are very old and well inhabited. The people who live in some of the well preserved old towns have good material to offer in the way of historic information. The time at my disposal, however, compelled me to make my visits as brief as possible and I prolonged my stay only at places where the prospects of obtaining material were promising. Even at this a good collection of legends was noted, which I hope when presented, may contribute its share toward the comparative study of the North Pacific Coast peoples.

On August 22nd I boarded a northbound steamer at Haines, a small town where I made my Alaskan headquarters for nearly four years, and went to Skagway. After two days in town I sailed on a southbound British steamer, and in about forty-two hours landed in Prince Rupert, a town of about three thousand inhabitants.

Image Number: 14905

The salmon canneries, where most of the Indians are employed, were then about closing their busy season, and families of various races were moving to towns like Prince Rupert, apparently to celebrate their prosperous season. Here one sees Chinamen, Japanese, Philippinos, Norwegians, Mexicans, all rubbing shoulders with the Haida and the Tsimshian. These Indians pay no attention to men coming into the town from other tribes or other nations, each looks after his own affairs, whatever they may be.

During my first two days in Prince Rupert, I walked in all directions in search of an Indian settlement or a temporary village, but there was none to be found. On different occasions I inquired of persons, who appeared to me true members of some native family, for the Indian settlement that I had heard to be somewhere in the neighborhood, but always met with the usual answer, “I don’t know.”

One evening I wandered across a typical Tsimshain, that is I learned later that he was of this tribe, a young man of about twenty-three years of age. When I hailed him in the customary way he stopped with a rather confused expression on his face and while he looked me up and down, I asked the usual question, “Is there an Indian settlement around here; where do all these walking on the streets live; to what tribe do you belong? I am a Tlingit from Chilkat, across on the American side, I want to get acquainted with the Indians down here.” After a moment’s hesitation the Tsimshian answered in a sarcastic fashion, “I don’t know any Indian village, I don’t associate with the Indians, I am from the south.” In answer to an interruption, he said “Vancouver. I am here,” he went on, “to see what’s doing at Rupert, and no sooner than my landing I struck a job, a snap believe me, paying me three bones and a half a day, and only eight hours easy work at that. . . . The work? why, er—pack fish, see, I pack them frozen in boxes for shipment. . . . Those people across the street? why, the girl in the white coat is my cousin, she is a waitress in the . . . . . . . . Cafe, lots of swell people eat there. . . . Yes, I’ll go there with you tomorrow night. . . .Where do I stay? why, I am staying at the . . . . . . . . . Hotel, and it cost me two dollars a day for my board and room to stay in this hotel and give you a lot to eat and a good spring bed.”

Image Number: 14910

At the appointed hour, on the following evening, we entered the cafe where the cousin of my guest was to wait on our table. The odor of beefsteak and onions met us at the entrance. The long bench at one side of the room was filled to its capacity with men of many unknown nationalities, perched on high stools, expressing mirth each in his own fashion while waiting for food. The sounds of the manipulation of knives and forks by those who were already partaking of their supper reminded me very much of a gambling hall in a Mexican town. A Japanese, from his station behind the counter, motioned to us to go into a small compartment off to the other side, inclosed by a brightly figured calico curtain, where we were seated and served after about half hour of waiting. Here ended my association with one class of coast modern Tsimshian, the tribe which at one time claimed that the sun rose only for the Tsimshian.

On the early morning of my second day in town I met on the street two middle-aged men of some native tribe. Upon greeting them I inquired for the Indian settlement. Despite the protest of the other, one of them pointed out to me a large mill, which could be seen at one end of the town, where he said most of the Indians lived. On my way down to this mill, I caught up with an old man accompanied by a pretty little girl on their way in the same direction as mine. After I returned his very polite salutation I once more inquired the whereabouts of the Indian settlement about the mill. He answered that he was a stranger from up the Skeena River, and that he also was out in search for the settlement, so that he and his little girl might put up for the day.

The old man, even though homeless at this place, showed every sign of welcome, so we joined—the three of us—in search for the former customary welcome of our race. When we arrived at the gate of the mill-yard, we were met by a guard who informed us that the mill did not employ Indians, and that there was none living in the neighborhood. To work off our disappointment, we sat down among the boulders on the beach, and here the old man in his broken English related to me very briefly, the discovery of Dagel-ha by his ancestors, an old town on which now stands the modern town of Prince Rupert.

“Long, very long time ago, tem-lex-emet (a native name of an old town, nonexistent, located near Hazelton) man, he find big trouble in home. He come down Skeena River, his children too, he come down. Long time he walk, pretty soon he come Git-selas, no the town chief he no like stranger, he mad, tem-lex-emet man he want to stay, no, the town chief he too strong, so my people he go away. He walk again long time, he stay one place just little, no good hunting. Many time he see other Indian and his children and the other Indian all the titre he no want him stay. He go many place and he no find friend, long time he walk, no find home.

“One day my people he come this place, he see bi—g water, more bigger than Skeena and no can cross, pretty soon he go that way (he pointed up the coast), no, he too hard trail, he come back here, and pretty soon he like it, pretty soon he find good hunting in big water and he make canoe. Afterwhile this place he allright, and Skeena man, my people he stay long time, and many children he born. He go hunt them Islands and he kill many seal, deer and many things he kill.

The modern Port Simpson is not like Lak-gelams (native name of the town) of the olden days, when the luggage of an arrival was rushed into the first nearby house. I cannot say where I might have gone to find a shelter in the downpour of rain, had it not been for a boarding house just opened the day before my arrival. The big frame house was pointed out to me as the only place offering accommodation to travelers, so I went there.

After hammering on the door for some time, I left my hand baggage and ran out to a trading store in the neighborhood. The trader informed me that the keeper of the place was out visiting and that I could just walk right in and make myself at home. I obtained from him also some information on the possibilities of getting to the mouth of the Naas River. I waited for about an hour after my return to the hotel when a young woman walked in with an air of authority. When she saw me rise from my seat, she showed signs of surprise, and in answer to my ready inquiry for the landlord, the Tsimshian landlordess demanded what I wanted, who I was and where I came from. I was very much unprepared to offer a decent reference, but she took sympathy when she noticed my dripping clothing. Later on during my stay, however, the young keepers of the boarding house, man and wife, became very friendly and treated me with much kindness.

Image Number: 14917.

My reason for mentioning how I was received by people of my own race, is to give my readers some idea of the difficulties that the investigator has to overcome at the present time among the modernized Indians all along the Northwest coast.

I spent about a week in Port Simpson, during which I did what I could to gain admission into the true character of the Tsimshian whose early history coincides with that of my own tribe, the Tlingit, to the north. The early Christian mission work has made a deep impression upon the minds of the people in general, so that practically no attention is given to preserving the old customs. Likewise, the native art of the people has made way for borrowed modern ideas, because the old was the result of heathen mind.

It was the method of most of the early missionaries, that if the savage man was to be civilized at all, he must be made to forget, as early as possible, his native ideas as well as his language. This is the mistake that the missionaries of today have to transform, and I think that it might take just as much effort to teach the modernized Indian to be original as it did to make him abandon his originality.

I am not criticizing the methods employed by the early mission workers, nor do I blame them for not understanding fully the true heart of the primitive man. True enough they have done some good in behalf of some classes among the tribes. I make this statement only to point out why some native persons appear selfish, false and sometimes silly.

Toward the close of my stay in Port Simpson, I was called on to address the people of the town. I held my audience in their church. Since my talk was announced to be given on Sunday I was rather compelled to express my true Indian feeling under the influence of the Christian religion. To the disgust of some modern young persons who were in my audience, I appealed too strongly in favor of encouraging the true character of the old time Tsimshian. There were many of the old people in the room, who had lived and learned during the early days, and who expressed much delight in my reception.

I took photographs and notes of things as they appear under the great force of foreign influence. I traced various historical events from some known points, but often found myself strayed into confusion. The very rich old history of the Tsimshian people is fast fading away by the appearance of civilization, very much like the ancient dead glaciers, in their neighborhood, by the heat of midsummer sun.

At the end of my one week’s stay in Port Simpson the strike was over and I left the town on the first northbound steamer, to the mouth of the Naas River. It was late on the following morning when I landed at Mill Bay, a small fishing camp, and in time to catch a motor boat sailing up the river.

From here one passes through a very rough, broken mountainous country, with hardly a decent landing where a boat could be pulled up by other means than sailing. To be compelled to ascend through this lower stretch of very soft bottom without the use of sail must have been a tough undertaking for the old time Naasman, as the powerful engine just about moved our boat against the strong current. The river, however, was in a condition so that the kind of craft we were using could be navigated without much difficulty.

About nightfall we reached Lak-gal-tsep, formerly an old Nassman town, now very much modernized. The town appeared to be abandoned, only one of the many rustic houses was then occupied. The old man and his wife, who were the only inhabitants, had the whole place to themselves. They came down to meet us at the landing and presently offered our party a shelter for the night. The old man revealed to us all that I had learned of a former hospitable Naasman.

Our very modest hostess seated all of the Indian travelers in her food-preparing house, where she served some of her own prepared foods in a real native style, while the host entertained us by telling some stories. Even though I would catch only a word now and then, I showed my appreciation by a smile whenever the others laughed, and a young man next to me would interpret some of the comic remarks made by the old man.

Image Number: 14920

I was not at that time fully accustomed to the Naas people’s way of eating, nevertheless I felt as if I had just finished at a table of some New England family after we were through with our rather primitive supper. I enjoyed it because this was the first time since my boyhood days in Chilkat, that I squatted down to my meal on the floor of a smoking-house.

I really cannot say whether or not I had any sleep during the night in the big frame house where we were placed. I must have dozed off for a moment, because when I unwrapped my steamer shawl from around my head, my lips, the only spot exposed in order to breathe, felt like two boxing mitts rubbing together; they were sucked about dry, If ever I go into the interior of Northern British Columbia again, I shall surely remember to carry with me some kind of a protection against an insect called mosquito, it seemed even hot coffee could not be sipped without one or two of these very bold creatures plunging into the flow.

Before sunrise on the following morning we left Lak-gal-tsep. From here on up we frequently sighted Indian settlements, many of which were pointed out to me as the same old towns where the Naas people’s mythology began. Some of these old towns are still in a standing condition, though most of them are abandoned. Among these may still be seen the old town of Git-iksh, the same town told of in one of the Tlingit myths. The remaining section of the old place is not as large as what we hear told in the story, but the ruined foundations of many houses testify to its importance in the days when the mighty Sun lowered his human offsprings (the ancesters of Tlingit Nehaadi family) to the earth in a huge stone bowl.

Our progress all the way up to the headwaters of the river was rather slow, but uninterrupted until we came in sight of Sieeks, (the name of the place is said to have been derived from the river), which only since the volcanic eruption has taken its present course. Then the river began to appear like boiling, and even our powerful engine became helpless. The very rough rapids in the Java formation of a canyon appeared as if even a spring salmon might find much whirling about in ascending the half mile stretch, but our skilful master was successful this time in punting and towing through the unmerciful torrent.

After crossing the canyon the river followed the main channel, and it was only at some of the smaller rapids that rough waters were encountered. The depth of the mighty Naas was in our favor at the time, and we made the trip to the upper part in two days.

My great fortune on this trip was an acquaintance offered by a very kind lady, Mrs. McCullagh, the wife of Reverend James B. McCullagh of Upper Naas Episcopal Mission. This lady happened to be on her way up the river on the same boat, and upon our arrival at Aiyansh, an Indian town where the Mission is located, I had the pleasure of meeting the Missionary also. These very kind people offered me a shelter in the Mission house, where I was given all the comforts of a real home during my stay in town. It was through the influence of this Missionary that I was allowed many privileges among the Indians, and he is one of the very few I know who showed much sympathy for the natural self and ideas of the native man.

There were only a few old families at their homes at the time I came to Aiyansh, as it was yet early for most of the Indians to leave their summer hunting places. To my good fortune, the families I found at home were those still dreaming of the caste to which they belonged during the bygone days, and with much pride told of the dignity of true Naasman in those days.

I took notes of things that were offered by some of the old men, and procured from them a collection of good old ceremonial objects for the University Museum. Among these is a complete ceremonial dance outfit which belonged to one of the secret societies of Naasman. I obtained also some facts with regard to the performance of the society which used the outfit.

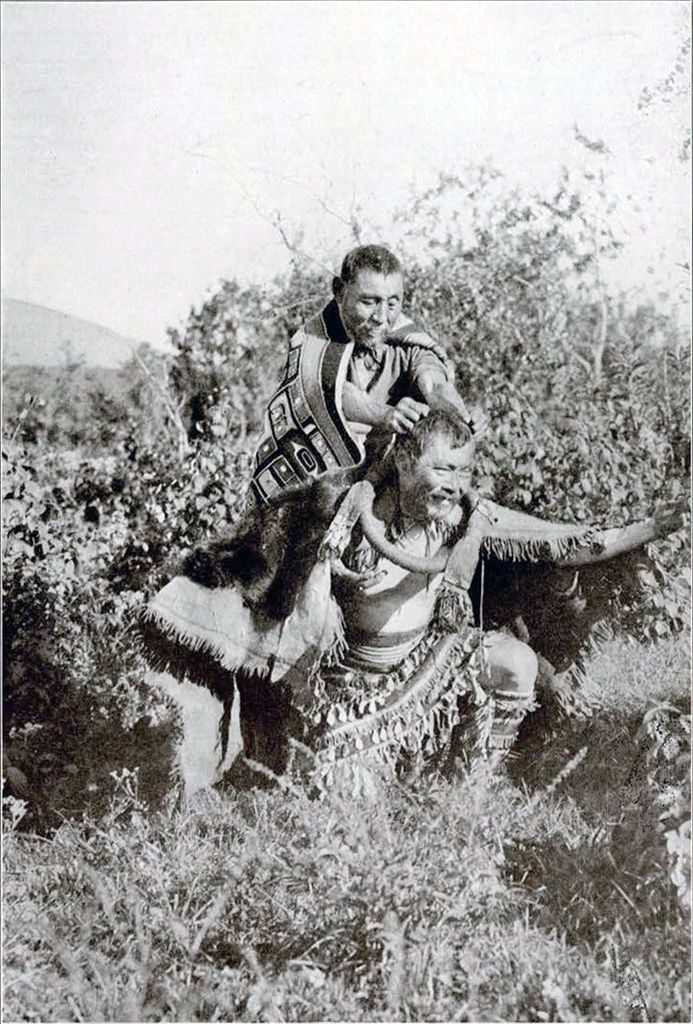

Chief Derrick, from whom I obtained the outfit, informed me that among many other secret society dances, only two were popular and these were performed only by the princes. One is called, in his own language, “Mi-la.” During this dance the performer destroyed property of any value that might be within his reach and later paid for the same with objects of greater value taken from the property brought out to be distributed among opposite clans who witnessed the ceremony. The other is called “Lo-tlam,” during which dance the performer ate dogs. It is stated that the performer had started to eat the animal while it was alive. In both performances, a large quantity of property was presented to the onlookers, and in course of time, if a prince was fortunate enough to complete the number of exercises required in each dance, which were eight, he was recognized as a high caste. I persuaded the chief who is said to have performed the latter dance on two occasions during his earlier days, to give me an illustration of the performance. This I photographed as he went through the different acts.

From Aiyansh I made frequent visits to Git-lak-temiksh “Man-of-town-on-swamp,” The name of the town was derived from a swampy space at the foot of the high embankment on which it is located, and like many other places the name was applied to its inhabitants by people of other communities. This very old town was situated on a high bank of the river, about two miles upstream. It is said to have been formerly occupied by all the people of this division, and that only recently, or about forty years ago, most of the people or those who were convinced that the life led in the old place was heathenish, had moved and found the present town of Aiyansh. But since the overflow of Naas, during the year of 1917, which destroyed much property, this same people who had made the change, are again moving their houses back to the old town. Most of the memorial poles are still standing, indicating where houses of the old time Naasman stood. Many modern rustic houses have been built up to surround it.

Git-lak-temiksh is now the last Naasman town up the river. It is said, though, that there was a town called Git-en-gelk, located further up along the river about nineteen miles from the present town which was the original home of the people. The change was made since the great traditional Flood, by a small party, the survivors of the once great tribe of upper Naas, who located here after their return to the valley from Sha-gut (the highest mountain in the neighborhood) where they had taken refuge during the high water.

Tradition tells that when the great sea began to cover the earth the Naas people fled up to the different high mountains. It was the small party who had wisely anchored their raft on the peak of Sha-gut that survived the once great tribe of upper Naas.

After the land appeared in the Naas valley the small party worked their way down to where they thought fish might be found, as the fear of starvation was just as great as that of being drowned. For a long while they searched and never found food, until they came to the place where Git-lak-temiksh now stands. The place appeared to be more suitable than their former home, and here the survivors decided to settle.

About that time there came people of some foreign tribe in search for a home where there were no floods. This party pointed out their original home in the northern direction, and in later years were identified to be of Tlingit origin. The two strange parties met on friendly terms and agreed to dwell together in one town. In later years the immigrants became a division of the Naasman, but their descendants, who still go under the name Te-que-di (a phonetic modification of the Tlingit word Tay-que-di), to this day are called Hay-gun-ho-did “arriving refugees” by the Naasman who always dwelled in the upper Naas. They are recognized, among various communities where they are found, as an individual clan.

I was informed by a Tsimshian that in recent years some of the Hay-gun-ho-dids had returned to their original home in Alaska where they became Tlingit once more. This bit of information corresponds to the many incidents that I have learned among some of the Tlingit families who trace their origin to the Tsimshian country. In fact most of the incidents told in the Tlingit myths have taken place here, for instance, “The Raven Traveling,” a Tlingit myth, was started in the upper Naas River, and on different occasions my Tlingit informants had remarked: “When we were yet Dahgel people,” Dah-gal, as Tsimshian pronounce it, was an old town located near the mouth of Skeena River. Obviously this part Tlingit had spread through various places in this region. I was informed too that while a few of the Tlingit were scattered among the Tsimshian proper, most of them had grouped together and found their own towns where they dwelt by themselves.

The Tlingit speaking people of Southern Alaska unanimously say that they migrated from the south, but whether or not they were formerly of a Tsimshian stock is still a mystery.

I do not intend to relate in this article the history of the Tsimshian people, as the space allowed here is not sufficient to do the subject justice. I have, however, made this very brief statement in that relation only to give my readers some idea how the various communities all along the river were originated.

I regret that I did not have more time to collect material for a complete history of this very interesting people, but it was then late in the season and I had to make my visit as brief as possible in order to carry out my plans up the Skeena River before the snow blocked the way into the interior.

I had spent only a week among the Naasman when I was compelled to take my leave. It was early in the day when my boat arrived in Mill Bay, the same camp where I started going up. From here I went on a cannery-tender to Gin-qolag “Place of scalps,” ter Kincolith (Tsimshian name Anglicised). Again, I was thrown among the kind of Tsimshians who imbibes the abused knowledge of civilization which intoxicates him just enough to pervert his own talents: I did everything that I could think of to make this community give me some information on things that I thought might help me in connecting the fragments of things on hand, but like the people of many other coast Indian towns, each Tsimshian here is too occupied in forming schemes that might push him ahead of the other fellow.

There was a wedding on the day I arrived in Kincolith, and another one on the following day. I was informed that there was one planned for each of the six days of that week, and there must be at least two thousand visitors from the neighboring places crowded into the small village to celebrate. During the first ceremony I was photographing right and left when a middle-aged woman pulled on my coat and when I looked she motioned me to follow. As we Went through the crowd she said: “You are a stranger, but the table is set for anybody on the street, so you must come and partake of the feast.”

We came into a large room where hundreds of people were already seated at long tables, all piled up with slices of bread, cakes, apples and many kinds of canned foods. I felt like an important person when I learned later that I was seated at the table of the town council.

After some of the old men exchanged speeches the feast began. Several large kettles of stewed venison were placed along the aisles. This was served to the guests by a number of well-selected waitresses, all. dressed in white. The first part of the feast was carried on by the younger people to suit their own liking, but many old timers were there too, who came to offer contributions in their own fashion, and regardless of all the modern arrangements some old person would step out from the crowd to cry out a name of some guest to a box of biscuits or a dish full of apples and other foods. These were pased on in many directions through a great chorus of many •voices of people who all seemed to be in a rush to dispose of their gifts. Many kinds of staple foods were distributed among the guests in this same fashion and with about the same spirit of Naasman of the old potlatch days. I was presented with a pile of good things to eat, but to my disappointment, I could not then think of a place where I might take these things, as I was yet without a shelter. I was relieved, however, by an old man who sat next to me who accepted most of my presents, and I took away only a box of soda biscuits and some oranges tied up in my handkerchief; these I carried under my arm with my camera for the rest of the day.

On the early morning of my second day in Kincolith I learned of a motor boat ordered to go to Prince Rupert for more things to be used in the daily feasts of the week, and on this I made my departure. The men on the boat were kind enough -to make a ‘stop to let me off at Port Simpson.

By the time I was nearly through the Naasman region, an annual fair was announced to be held in Prince Rupert, at which most of the Indians from both Naas and Skeena Rivers are in the habit of attending. This in a way compelled me to repeat my visit to Port Simpson, and spend one almost fruitless week before I took my Skeena River visit.

Near the close of the fair I returned to Prince Rupert, and as soon as the Indians returned to their homes, I started on the Skeena River. On the twenty-second of September I arrived in Terrace, a small town, on Skeena River, about ninety miles from Prince Rupert. From here I took my daily walks to the Indian villages in the neighborhood.

L.S.