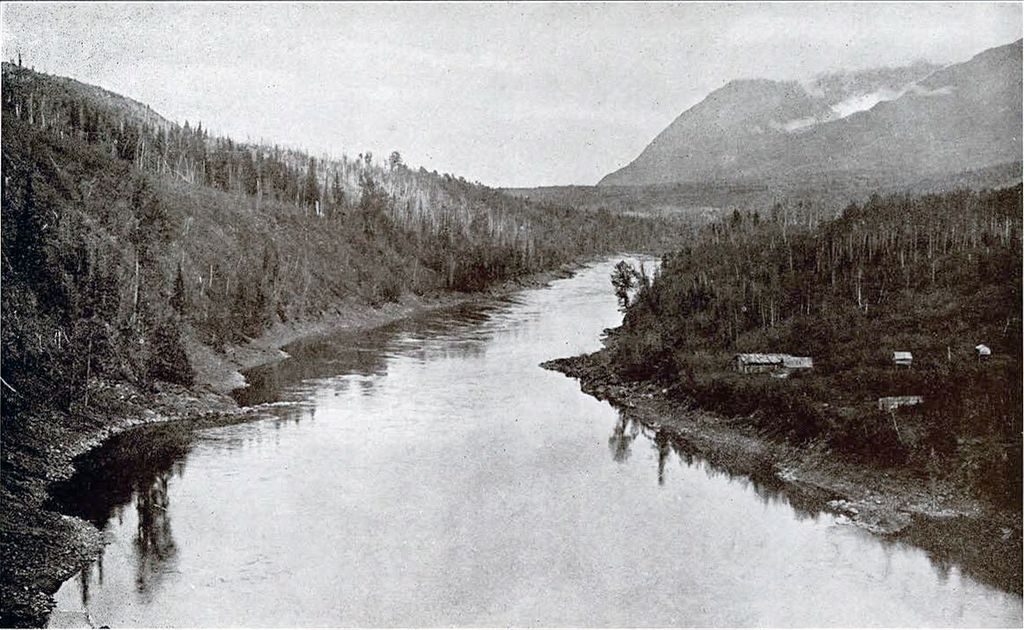

The Skeena River

Image Number: 14931

On the evening of the first day in Terrace, I learned from the few Indians wandering around the town that Gitsumkelum, a native village of which I had often heard, was not far downstream. Early next morning I walked out to the village. About four miles below Terrace there is a river emptying its waters into the Skeena; after crossing this I met a wayfarer who informed me that I was in Gitsumkelum. I was rather disappointed, as I had expected to see an old village, but there was nothing like that in sight. The traveler, however, pointed in the direction of a forest of tall cottonwoods, where he said there was a small settlement of Indians. I was working my way through a thick growth of willows, across what had been an island during highwater, when I caught sight of someone walking out from the woods ahead of me. When I came near, I found a young girl dressing a fresh salmon. Because of the noise made by the continuous swishing of the running water, I presume, she did not hear my footsteps, since the busy hands went on as if unaware of my presence and she never looked up until I spoke. When the Tsimshian girl saw me standing near, she immediately put her attention back to her occupation, without even showing the alarm that might have been expected where strangers in a remote place are thrown face to face. I had to repeat my question about the location of the village before she spoke and then without even changing her attention, she gestured and said, in a rather peculiar voice: “Down there you will find my father, go and ask him.” In this glimpse of shyness I recognized a true daughter of the old time Tlingit. Even though I had been taught to observe such etiquette during my boyhood days, it was strange to me, after associating with modern Indian girls, to come face to face with a reserve which is fast disappearing. I backed away, playing my part as a true son of a family who at one time taught their children to know their own station in life.

As the girl directed, I found a native food-preparing house almost hidden by a growth of willows. For a moment I stood at the open entrance and in answer to my knock a voice came from one side. I entered and there found a woman squat on the floor, slicing half dried salmon on a triangle-shaped stool, a familiar scene to me. Over head, under the ceiling of the roof, were closely arranged on racks, sheets of sliced salmon hung on their edges, and on both sides of the room under shelf like smoke spreaders were cottonwood logs lying over small open fires, each sending out puffs of smoke to the ceiling. Upon seeing me the woman called out in her own language to someone; a man appeared in another opening of the house and came forward with his own fashion of greeting. After we exchanged a few words in English, the man motioned me to follow him. We walked out of the smoke-house, down to the river’s edge and here he took a seat on a wooden box to continue the mending of a gill net which he apparently had just left. The man spoke English fairly well, and after I told him my name he asked me if I was related to someone whom he had known. He appeared to enjoy telling me of the friendship which at one time existed between his father and my own paternal grandfather during the latter’s frequent visits to the Tsimshian country from Chilkat. The man named to me, in his own tongue, many native towns along the Skeena which I noted in order; commencing at the lower end, he indicated just where the boundaries of each division occurred. I obtained from him also some other incidental facts which, with the derivations of some of the town names, proved to be useful later on.

Tsimshian Hospitality

We were very much interested in exchanging stories of the past when I noticed the young lady standing near as if awaiting an opportunity to speak. The father turned his head to her, the girl said something in her own language, and the man asked me if I could take “tea” with them. After accepting his kind invitation the man led the way back to the smoke-house. In the house I saw another young girl, the two standing in one corner as if awaiting some order. On one side of the room, near a blazing open fire, were laid out on the plankless floor some fresh red cedar boughs, on the fire side of which were placed two clean boards with a number of well worn sheep-horn spoons arranged upon them. On the boughs the master of the house seated himself and pointed to me a place next to his. After I had squatted in my place my host again said something in his own language, and in response to this the young lady whom I met first left her work and took a seat beside me. This is another custom that I recognized to be similar to that of our own in Chilkat. Among the Chilkat people a host requests the presence of his best friend when entertaining a guest from another region, and in the absence of such a friend the daughter is invited to take part in the entertaining.

Image Number: 14941

The hostess placed before us our meal, and while we were eating the well broiled fresh salmon, she was busy preparing the wild berries. The mistress of the house, however, never joined in our meal, she waited until we were all through. While she and the young lady who had assisted her ate their food the host continued the story which he had started at the beginning of the meal and did not change his position until the two had finished. After lunch my host offered to take me around to the old town site which he had referred to in his story. We walked back less than a hundred yards when we came upon a space where could be seen only foundations of many houses, most of which were nearly covered by the thick growth of weeds, while corner posts of some were still standing. This, he said, was where the second Git-dzem-gay-tlon (as the Skeena Tsimshian pronounce it, which, when translated, means “man of ridge dwellers”), stood up to very recent years. While we were going through the wreckage of the old town, my guide called attention to some people paddling down the river at some distance from where we stood, and he guessed right away who they were. “This is Gago-gam-dzi-wust returning home” he said. “This is the right man to be a chief of this place, but had his people lived he would have caused them much trouble, because he is not friendly to the head people of other villages; but he is a good man just the same, I hope that you will make friends with him.”

Just as the man finished telling about his neighbor, the canoe landed a short distance from where we stood and a middle-aged man and a young woman got out and began to take their baggage ashore. We walked down to greet the arrivals. After we became acquainted the chief pointed in the direction of the wood in the rear where his house stood and invited me to call there some time after they had moved in. “We were away in Alaska all summer and this is the first time, since last spring, we returned to my village, and I know my cabin is in bad shape to ask you to come now; but the grandson of my uncle’s friend shall be welcome to my poor home at any time.”

Apparently, my granddad in his lifetime had made many friends among the people in this region. I met other families who claimed his friendship, and this made me feel all the more at home with this people, even though I was handicapped by not knowing their language.

Image Number: 14942

I gathered from the Indians I met here that the old Git-dzem-gay-tlon, or Gitsumkelum as it is now called, was located some few miles up the Gitsumkelum River. It was built on a narrow plateau from which the town took its name. It is stated that the site was found by a man named Nish-gan, formerly of Naas River, and, shortly after this man with his family settled here, a party of emigrants, who in later years were identified to be of Alaska Tlingit origin, came from the direction of the Naas River to join them. In still later years, these emigrants became one of the divisions of this group. In course of time, when other parties from upper Skeena River came down to join the community, the place gradually grew to a very large town. It was divided into different sections, each section being a single row of houses arranged on level ledges staged down the embankment, and occupied by different phratric divisions. The town grew so large that on some occasions a visitor from one section to another disappeared, and stole and sold to traders from foreign regions, who frequented the popular town. After the European occupancy of the coast region, however, the people of this town began to scatter, and about forty years ago the last of them came downstream. These are now to be found living in the new Gitsumkelum, a village located at the mouth of Gitsumkelum River, where it pours its waters into the Skeena, about ninety miles easterly from the town of Prince Rupert.

At the time of my visit, during the autumn of 1918, there were only two families, numbering about a dozen people, living in two rustic houses. Like most of the groups along the river these Indians are not always in their village, as their chief occupation, which is fishing and hunting, leads them away during the different seasons. During the summer months they are employed at the fish canneries along the coast.

The natives of this region called the Skeena River “Kshen,” and the people who inhabit the many settlements all along the river, from the lower end up to the headwaters, are called, collectively, “Git-kshen” which, when translated, means “Kshenman.” It may seem that the Gitkshen are in the main nomadic, and it has been stated that prior to the present position of the various groups, extensive migrations of the older generation had taken place over wide stretches, but many things will be noticed, as I go on, as evidence that up to the time of the European occupancy of neighboring regions, these people were living in fixed habitations. This does not necessarily imply that an entire year was spent in one place. Agriculture not being practiced during former times, the people were compelled to make occasional changes from their permanent homes to some distant waters and forests to procure supplies of food. When furnished with food and skins for clothing, the hunting parties returned to the villages which constituted their true home. This is true also with the people inhabiting the villages along the Naas River.

At the first opportunity I paid the visit I had promised the chief of Gitsumkelum, during which we talked on many subjects concerning the life of the people who used to meet here before our time. Before we went far the chief informed me of his relation to the Tlingit of southern Alaska. “Do you know,” the chief started, “my grandfathers came to this country from Alaska? I felt as if I saw my own brother when I found out who you are. We used to be Alaska people. I want to tell you how my grandfathers came here.” The chief then began the legend. The story, of course is rewritten, changing some words to those which I thought might offer a clearer interpretation of the narrator’s meaning.

The Migration

There were two tribes in villages right opposite each other, at the mouth of a salmon stream running into a salt-lake called Nah-ah’ in Tlingit, which is a bay near Loring, Alaska, on Revilla Gigedo Island. The Eagle group of the tribes was led by a man named Kitch-tu-hini “Flooded wings” (when an eagle caught a fish its wings were flooded), and the Wolf group by a man named Gish-naga-núsh. The two parties dwelt in peace for a time.

The bay which is a formation like an alcove, has a narrow opening to the fiord on the outside, through which, at high tide, it is filled with sea water. With the rising of the tide many kinds of sea animals flocked into this lake presumably lured by fish, and when the tide ebbed the water in the lake became shallow, when it was easy to kill these animals with spears. The drove of incomers was so lively in the pool that often times a salmon or some other kind of fish was left dry in some of the smaller cavities along the shore. It was by this that a man from the Eagle group thought of a. scheme which, later on, proved a success. This was an artificial rock dam, inclosing one corner of the lake, constructed so that at high water the top of it would be well under the surface so that seals and other animals would flock over the rock pile. While chasing around here, unaware of the ebb of the tide, the upper edge of the rock pile rose above the water line and trapped them. The inclosure drained almost dry, and then the seals were killed with clubs by the Indians. It was said that when the dam was first installed, it caught or trapped enough seals to supply all the families of both communities, and during their seasons fish of many kinds were also caught. As time went on the catch in the dam gradually lessened and the Eagle party who owned it could no longer spare enough to supply all demands of the other community.

Gish-naga-nush, the chief of the Wolf party, made an attempt to copy the invention of the Eagles, but could not locate a suitable spot where another trap could be made. Toward spring food supplies in both communities were well consumed, and the Wolf party then were depending largely on what might be spared by the owners of the rock trap, because the weather often would be too rough to do any hunting on the open channel.

The Death Of The Indian Bride

After a time Gish-naga-nush asked for the hand of the Eagle chief’s young daughter; in this he succeeded and took the girl for a wife in addition to one he already had. The Wolf chief thereafter, by tribal custom, was entitled to a division in the catch made by the rock trap. Gish-naga-nush perceived the great affection of the rival chief for his daughter, and the rapacious man took advantage of this at the first opportunity. He renounced ownership of all the property that his father-in-law had offered as a dower, and instead of this demanded more than his share of the daily catch made in the rock trap, which already had shown great decrease. Kitch-tu-hini could not supply all the demands even of his own group, hence he was not in a position to please the husband of his only daughter.

Gish-naga-nush one day was trying to persuade his young wife to make an appeal to her father to grant the demand, but she well knew that if her father acceded it would displease his people, so she refused. This argument developed into some cross words between husband and wife, in which the chief, overcome by his bad temper, hit his young wife on the head with his staff and probably fractured her skull. The injured girl was immediately carried back to her father’s house, across the creek, where she died.

Image Number: 153760

Kitch-tu-hini immediately sent an order through his village that no one weep, mourn or even mention the death of his daughter, and that the news of the death should by no means reach the ears of Gish-naga-nush’s people. During the sound sleep of the villages on the following night the body of the girl was buried, instead of being cremated, which was the custom of the people. Meanwhile, the chief’s son who was younger and had the features of his murdered sister, “made up” to impersonate her. The young man in some way attached a wig made from the hair cut off the dead girl’s head, dressed himself in the garments she wore, painted his face with pine-pitch and covered this with powdered burned hemlock fungi. In this disguise the youth took his position in his dead sister’s bed.

A day passed with Gish-naga-nush getting no news of his absent young wife, and on the next he sent a messenger to investigate, who reported to the chief that his wife was still confined in her sick-bed. As the days went by, however, the news came that the injured wife gradually improved, and finally she had recovered enough to be able to appear at her meals with the rest of the family.

At all times, whenever anyone from the opposite settlement was within hearing distance, Kitch-tu-hini would make a remark expressing his impatience for a happy reunion of his daughter with her lonesome husband. This, of course, would reach the ears of Gish-naga-nush, for whom the remark was really intended. The chief, apparently, bore for several days the longing to see his beautiful young wife, finally became impatient and could not wait longer. One day he sent out for his maternal aunts, his sisters and all the female members of his clan, to meet with him in his house. When all the women were seated in the large room the chief came out of his sleeping apartment, where he had spent most of the time since he had committed the crime, and to them he expressed his wish. He instructed them to express to his wife and the women of the opposite clan his sincere regret and apology. Then he requested the party to bring back to him his beloved wife. The party of women went on its mission and at dusk returned in company of the chief’s supposed wife.

Upon entering the chief’s house the unsuspected young “wife” retired immediately to her private apartment. This act, to the members of the house, was no more than natural of any young girl who is ashamed to show her presence. As much as he wanted to come to his wife, the chief showed that he was compelled to observe all that is demanded by proper etiquette, and not for anything would he again hurt the feelings of his young wife, so he had to leave her alone. The young “wife” spent all of the following day in seclusion and was not seen even by her own husband.

When night came the young man was sitting up when a body. servant came in to inquire as to any needs. With the girl slave he went out only for a moment, but dismissed her as soon as they returned to the room. Presently the chief came in to him in his murdered sister’s sleeping room, and laid himself down along side of him, but when the chief touched him “she” whispered that she wished to be left alone as “she” was still suffering from the unhealed wounds. Out of respect the chief had to obey. and lay still.

Image Number: 14953A

In the meantime, over in the other settlement, Kitch-tu-hini’s people had made everything ready for what might develop from this well constructed plot, and were all on the watch day and night.

Toward morning Gish-naga-nush was sleeping sound. The young man moved around in bed, but the sleeper never stirred. He even raised the chief’s right arm high and then let it fall, but the sleeper still slept. The brother of the slain then pulled out one of the sharp knives which had been concealed about his person, and with one stroke Gish-naga-nush’s windpipe was severed, and with a few more the head was cut off. During all this there was nothing heard. After he straightened the covers over the slain chief, the young avenger wrapped his trophy in one of his dead sister’s fur robes. This he carried with him out of his enemy’s house and across to his father’s people.

At daybreak the people in Gish-naga-nush’s house rose at the usual time, but went about without making much noise, as they well knew that their leader was with his young wife and would stay in bed late. The day wore away, but the chief still slept. Towards evening, however, someone began to suspect that something might be wrong and began to inquire. This aroused the other members of the house. Finally an attendant was sent to see. Upon approaching the private section, there was much blood streaming out from under the partition. The slave rushed, pulled the mat curtain aside and raised the bed covers. In response to a wild shriek uttered by the slave, everybody in the house made a rush to the scene. Behold, there lay their chief, but his head gone—cut off. It did not require much investigation to find out how the tragedy occurred, for spies were immediately set to work under cover of the following night.

Fight Of The Tlinkit Clans

There was a rustic bridge across the creek, connecting the two settlements, and in the middle of this most of the fighting took place at daybreak. As both sides were about equal in power, they did not allow each other to cross. The struggle between the parties lasted only for a few days, but many men were injured on both sides and some killed. During the last interval of the fights, however, neutral parties destroyed the bridge, which left no other means to cross except by small canoes. And in this way the belligerent parties were successfully kept apart.

Image Number: 14954

Kitch-tu-hini, the Eagle chief, realized that there could be no more peace between his and the rival party, and after many councils with his people finally decided to make a move to some other region where they might begin life in peace. When this was made known, preparations were immediately put forward. In the still of one night the Eagle party broke camp and started on a journey to some unknown place. Many things that were too bulky to carry along had to be left behind. Among these was the crest figure of the clan, a huge rock shaped like an eagle, representing the main crest of the party. This, the chief thought, would be ridiculed if they abandoned it with the other things, so he ordered some of the tall totem poles cut down. These were formed into a large raft. On the raft the Stone Eagle was placed, and when the party moved away from their old home, on the outgoing tide, it was towed along. In the middle of the salt lake all the canoes paddled together and the Eagle party began to sing a song which had been composed for the occasion. At dawn they reached the fiord end of the frith, and here the Stone Eagle was rolled off the raft. The Eagle crest, as was presumed then, sank out of sight forever and the raft of poles bearing the family record, on which it took its first and last ride, was let loose to drift out into the open, never to be seen again. But it is said that at extreme low tide the Stone Eagle, until very recently, was seen lying in the bottom at the outlet of Nah-áh.

The emigrating party came to a temporary stop in a bay on the south side of where Ketchikan now is, and encamped. From here small parties were sent out when the weather was favorable to look for a suitable place. Some of the men were absent a number of days and reported the lay of the course in the southern direction. Before a decision was made as to what course to take, the cold began to set in, and the party was then compelled to remain in camp all through the winter months. During this time, it was decided that, in order to preserve the Stone Eagle crest, another one should be made similar to the original, which was immediately carried through. The new one, when finished, was the model of the one left behind, but owing to the unsettled condition of the party the size of it had to be much reduced, so that it could be carried along to wherever fate might lead them.

It was early in the spring of the year that the emigrating party arrived in a village, a short distance up the Naas bay. The place appeared to them to promise many good hunting points, and they thought they would stay, but the native people who dwelt there were far from being hospitable, and refused to have the emigrants remain as permanent residents. (The village referred to here must have been Git-hatan, a Naasman eulachon fishing village, situated near the mouth of the Naas River.)

After the Tlingit emigrants left the first place, they were turned away from other Naasman villages up along the river. They were handicapped by not understanding the language of the people who live in these villages and this seemed to be the reason for their failure in creating friendship with them. They, however, were allowed to remain for some time in a town near the canyon (evidently Git-wen-sheiko, a Naasman town near the canyon) and stayed here until they learned the situation and the lay out of the country. From this stop the emigration followed eastward, up along a river until a lake was reached. From the lake, across a very wild country a few more days’ journeys found the party following the course of a river leading to the opposite direction from the one they had just left behind, and finally they arrived in a small settlement, inhabited by people who spoke a language similar to that of the people they had left some time past on the Naas River. It turned out that the few people found in this settlement also came here from the Naas region by the same trail. They said that they too left their home because of some dissension there.

Image Number: 153761

The two parties met on very friendly terms, and decided to dwell together in one village. Later on in years, as has already been stated, other parties came down from upper Skeena who also became a division in this community. After the place grew to a large town, Nish-gan, the founder, lost all control of the place. As was to be expected the Tlingit chief never resigned the position that he had always held, hence he was recognized as a head man of the town. Since the settlement became known to the outside people, it was given the name, Git-dzem-gay-tlon “Man of ridge-dwellers,” by which it is known to the present day.

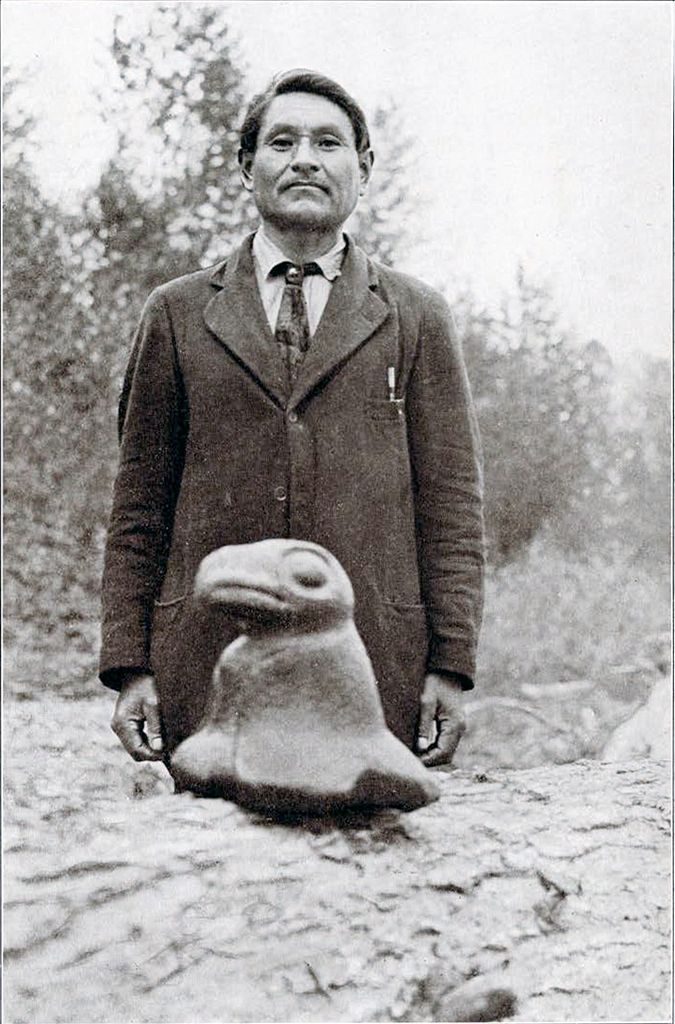

After he concluded the account of the migration of his ancestors, Gago-gam-dzi-wust said: “I still keep the same Stone Eagle that my people packed to this place all the way from Alaska.” When I asked to see this, the chief led me out of his cabin and made his way through the brush in the rear. We went only a few paces and at a certain spot, he began to dig a hole in the ground with the spade that he brought along with him. He dug down only a little way when he uncovered the rock which he lifted out and handed it to me. It weighs about forty pounds. We carried it down to the river, and washed the mud off. It is made of a hard granite almost greenish in color, hewn to the crude shape of a bird. (Fig. 47). After I photographed it I suggested to the chief that it would be a good thing for a museum, where people from all parts of the world may see and study it. He hesitated for a moment and then said: “I like to do that, if only I have something besides this piece by which to keep in mind the memories of my uncles and grandfathers, but this is the only thing I have left from all the fine things my family used to have, and I feel as if I might die first before this piece of rock leaves this last place.”

Modern Tsimshian Villages

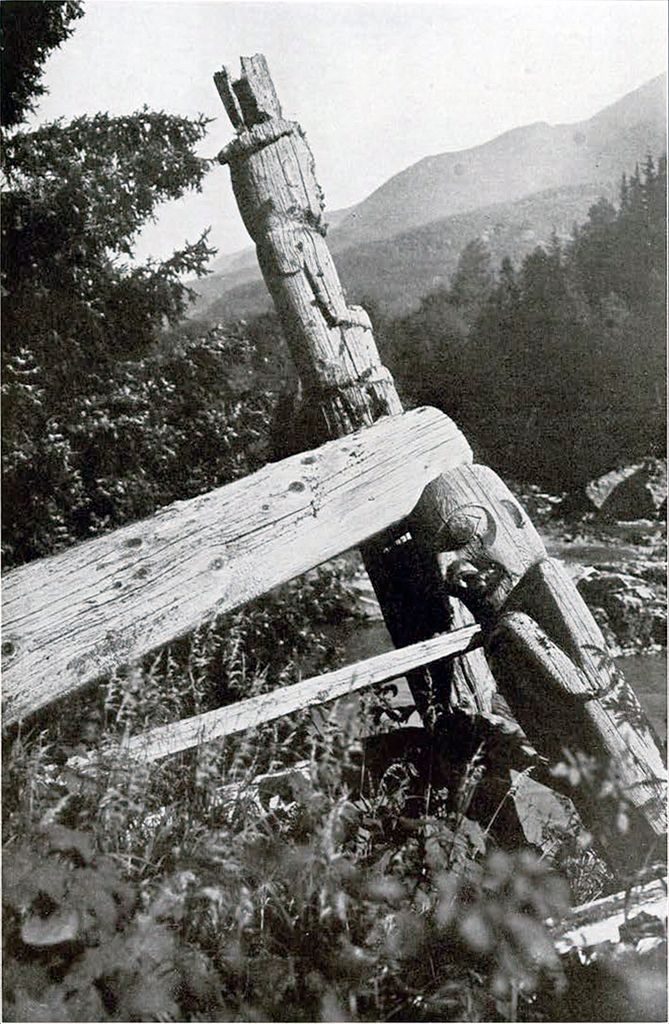

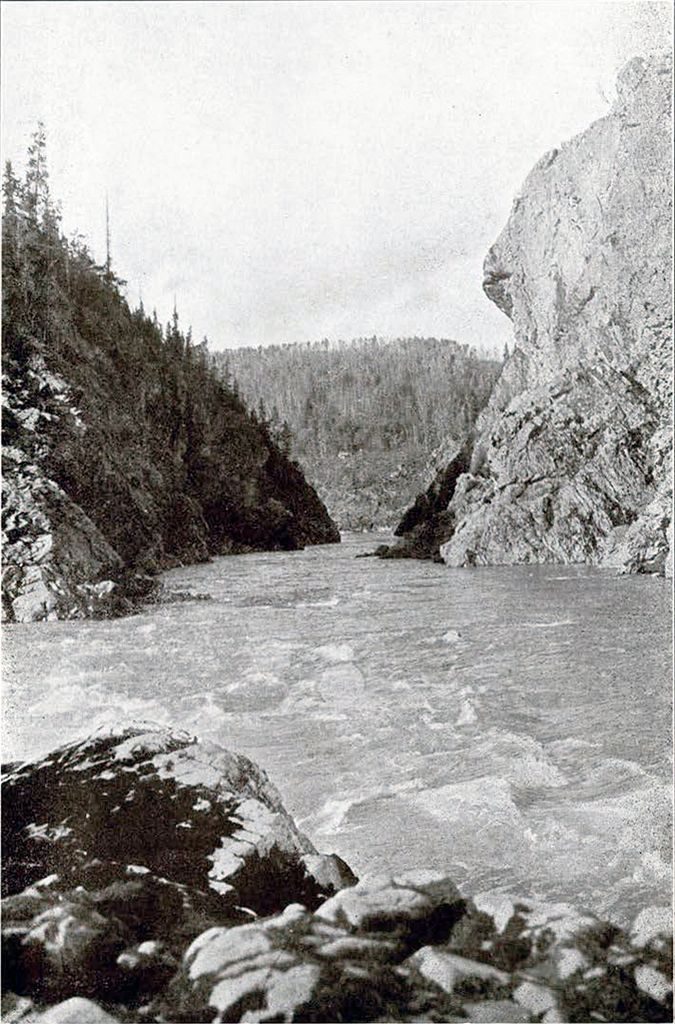

From Terrace I visited other small villages. About twelve miles upstream from the town, where the canyon takes in the river, was located the old town of Git-tzo-lesh-co “Man of canyon” or Gitsalas which, until recently, was occupied by Git-kshen people of upper Skeena, who are said to be its founders. It appeared that the town had been divided into two parts, each being built to face the other across the river. At the time of my visit some of the totem poles were still standing, indicating where the old houses had stood. The few families who lived here last had moved downstream, about four miles, where they formed a new settlement named Varnarsdol. The Indians in this village number about seventy.

On the northside division of Git-salas may still be seen, lying on the ground, many decayed pieces of wood carvings which I thought could have been preserved had the last owners cared. This led me to think when they could afford to leave these behind, that there were other things too which they considered worthless in their new life, and there might now be found slightly covered, some good Git-kshen archaeological specimens. If time be given for excavation, no doubt some stone pieces will be found lying close to the surface.

After I took photographs of the ruins I walked on farther, and about four miles from Git-selas I came in sight of Tlem-ge’ another abandoned native town, located on the south side along the river. There was no means of crossing from the side I was on, so I had to view it from a distance. From where I stood the village appeared to be much newer than Git-selas as some of the houses were still standing. I had learned that about half the people who lived in this village had returned to their original home farther up the river and the other half was scattered among the coast settlements.

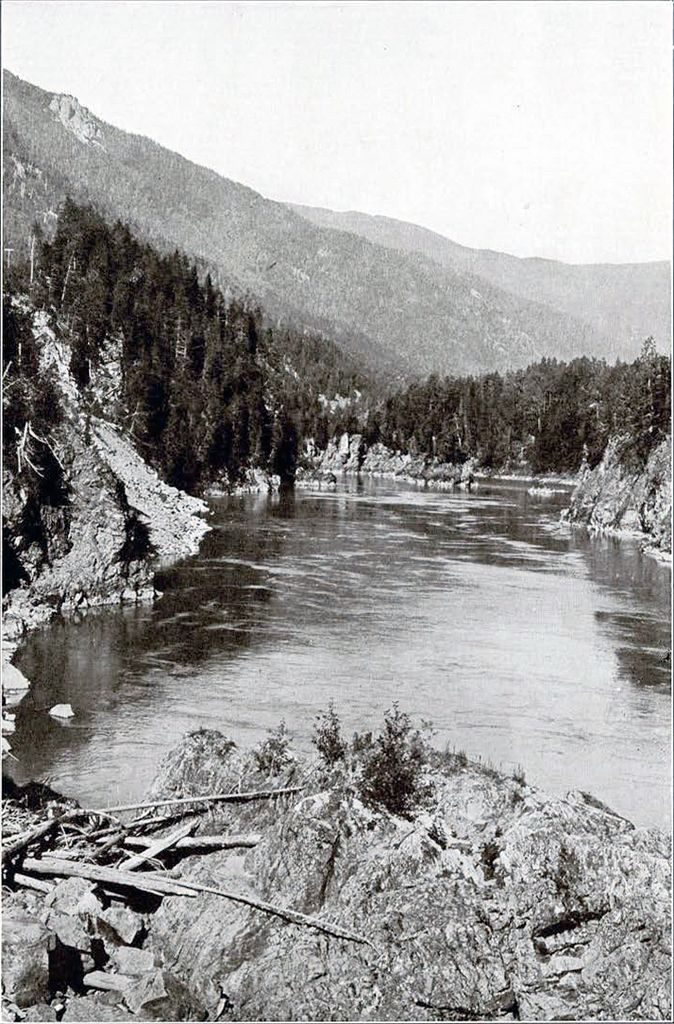

Skeena River is a picturesque turbulent stream flowing into the Pacific Ocean. One may see from the train the whirl of its currents. From its bed at many places there rise great rocks and along the shore steep cliffs, which had made navigation difficult during canoe days. Both sides of the river are fringed with mountains throughout the length of the stream. There is a gradual rise in elevation and diminution in the size of the river as the upper end is approached. From Terrace the river makes a gradual curve from the direct eastern course to the northeast and then continues to the north. The Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad follows the river all the way up to Hazelton, a town about 176 miles from Prince Rupert. This makes visits to the Indian settlements along the river no longer a hardship, but the more important places are those found in the interior, away from the railroad.

Git-wen-geh

On the twenty-eighth of September I arrived in Git-wen-geh “Rabbit tryst man” or Gitwanga as it is now called, an old Git-kshen town situated on the west shore of the river, about 154 miles up. At the time, the old section of the town was at about its last stage of occupancy. The Indians are building many modern dwellings in the rear and the old fashioned houses are used for preparing food. I was told that when all are at home they number about two hundred. These Indians are very industrious. Their fishing season is immediately followed by hunts for different kinds of game in the neighboring mountains. Since the fur market offers attractive prices to trappers, most of the houses are no longer homes but temporary camps or something like caches. The great demand for fur is the reason why most of the Indians are very seldom seen in their houses and why these appear more like unpainted barns. If one peeps through the dusty windows of some of the modern dwellings, the room is usually destitute of nearly everything that might offer comfort.

It is stated that old Git-wen-geh was founded immediately after the traditional flood by a few survivors of the once great tribe who formerly dwelt in a town called Git-tlu-sek, “Man of drawing-town,” which has long been nonexistent, located near the foot of Wish-ge-nisht (Seven sisters) the highest mountain, on the opposite side of the present town. It was on the peak of this mountain that the people of Git-tlu-sek anchored during the time the earth was covered by the sea. After the small party returned to the lower lands, they found themselves deprived of the way to increase, since the survivors happened to be mostly of the Raven phratry. And it is the custom among this people that no Raven man marries a Raven woman, so there they were, the men with their sisters and the women with their brothers. It became necessary to continue the search with a view to finding people from the opposite phratry with whom marriages might be made. Shortly after they came out to the Skeena River the Raven party met some people at camp along the river who happened to be of the Eagle phratry. The two parties together founded the town which in later years was named Git-wen-geh and to the present day they are recognized as the main people of the town. It is stated also that the two parties for some time lived in a village called Git-shullk, which was located on the east side of the river about opposite the present town, but later on Git-wen-geh proved to be more suitable for a permanent home. It was at this time that the Raven party disagreed on many things. Some leaders were of the opinion that the flood was a punishment on only the Kshen people and that there might be still among survivors of other communities, wicked chiefs who might bring more punishment such as the big flood. Hence, the Git-tlu-sek people had to sunder tribal relations and each division chief chose a direction in which to lead his own group. In later years it was reported that some of the emigrants did not go beyond Git-tzo-lesh-co, a few went to a village called Git-tziksh and one group is said to have joined a Haida party of the Queen Charlotte Islands, but the main branch of these emigrants was found at a town called Git-emat. Some years after Git-wen-geh became well known, however, the descendants of some of these groups returned to live in their original home.

Git-wen-geh is one of the few Indian towns where various groups from distant regions dwell together without one interfering with the affairs of another. I was told, as the town grew, many other parties immigrated to the place. The Eagles and the Wolves came from Git-lakdamix on the Naas, more of the Wolf clan from Git-dzem-gay-tlon on the lower Skeena and the Frog party came to live here from Gish-ba-yekosh on the upper Skeena. Even at the present time the town appears to be a center where families from the neighboring places meet on equal footing, and they come and go unnoticed.

Git-wentl-qool

While at Git-wen-geh I procured a saddle horse and provisions and one morning made my way into the interior. For a few miles I followed a wagon road along the Gitwankool River, but this good ride only took me out of the way that I wanted to take and I never knew I strayed into the wrong road until I rode into a ranch. The white man farmer was very kind in directing me to the right trail. From here I followed an old Indian trail. For some hours the irregular path wound right and left with the rise of elevation. The path was marked out by blazed trees where it led through the forests. Some of these few cuts were so old that it was hard to detect them and a stranger is forced to make occasional circles to get back on the right course. The river down in the valley, however, was in constant view, by which the right direction could be made out on the level benches. The sun was away beyond the meridian when I reached the summit. I was passing across what appeared- to be a slide when my pony suddenly refused to go ahead and acted as if undecided as to whether or not to take a leap down the steep cliff on the left of us. The animal had just sense enough to take a spin on its hind legs and made a few prances back to the bench we had just left, before we went through some broncho-busting acts. For some moments the spirited animal was beyond control, and I never imagined what had happened until after I calmed it down a little it occurred to me that the keen sense of a horse knows when bear is near. With my thirty-two caliber gun I could not do any more than fire a half dozen shots in the direction of a thicket where the animal centered its stare, but I am certain that most of the discharged bullets flew in different directions as the pony made another spin around just about as fast as the popping of the automatic Colt, so we did no more harm than to rouse a sleeper. I carried such a gun just to make myself feel that I had a weapon of some kind, but without a reliable gun it is not advisable to go to some of these places, where wild animals are. About a quarter of an hour later I led my pony by the spot as if all the bears were driven out of the way. At sunset we reached the low land and from here followed the course of the river. A soft breeze from the north brought to us a faint dog-bark from ahead and the cayuse put on more speed regardless of the almost invisible way ahead.

Image Number: 14961

Suddenly the pony ceased to gallop and gave me signs again that something was ahead, and then I saw rays of light twinkling against a growth some distance before us. When I rode nearer I heard the singing of many voices, and still nearer from the cover of almost black night I could see many faces against the light from a blazing bonfire—the people were dancing. I learned later that there was to be a potlatch, to which people from another community were to be called to visit this group, and what I saw here was a rehearsal in the open air for the occasion. At the end of the act I rode up, and when I hailed, those sitting down got to their feet. Presently the Indians were standing in half circle in front while one man questioned as to who I was and what I wanted from their village. I made myself understood as nearly as I could that I was no other than a friendly visitor, but the men appeared to be not entirely satisfied with the excuse I offered for my visit. I was directed to some one who the men said spoke the English language well. A youth who was sent with me to show the way led my pony through the darkened village. Before we reached the interpreter’s house an old man called after us and told the youth that the family we were going to see had left for their hunting grounds and that the house was closed. The kind old man offered that if it was all right with me I could put up in his house. In the front of the modern log dwelling the Indians again crowded around while we were dismounting and questioned as to whether or not I came in interest of the government. Regardless of my denial I know I was suspected by some of the men as an agent of some kind.

After they gave me my supper the old man and his wife left the house, leaving instructions with the youth to see to my sleeping accommodation. The youth and I entertained each otherwhile making up my bunk in one corner of the single room. After I rolled in, the boy stretched himself under a fur robe on a bearskin on the floor close to my bunk, and finally talked himself to sleep. After making a large herd of “sheep jumping over the fence” I got tired, so pulled on my boots and walked out of the house. It was about two o’clock in the morning, but there were still talking and singing going on in some of the houses. As I had noticed upon my arrival, everybody was drinking and in most cases individuals were too intoxicated to give heed to the hour of the night and while some were having a good time the others were in some kind of trouble. I found out later that this out of the way community is addicted to the manufacture and use of native-brewed liquors; this habit is said also to be practised among some of the communities along the railroad. I was told that the temptations during the last few years have been very great owing to railroad construction, which has brought large numbers of white men, who seem to have been only too willing to give liquor to the Indians even if it is against the law, and in many cases it is done in order to earn twenty-five or fifty cents. One authority had said that he had known some white men to buy an Indian a bottle of whiskey in order that they might be put in jail, as the men had no means of livelihood.

Git-wentl-qool “Man of reduced passage” or Gitwanlcool as it is now called, is a well-preserved old native town, situated in the interior about twenty miles north of Git-wen-geh. The name (cf. wentl-qool “reduced passage”) may have been derived from the deep canyon, a short distance downstream of the town, as the valley from about the lower end of the Gitwanlcool River appeared to be gradually reduced by two mountains, forming a high gateway near the upper end. In the village most of the native style of houses were still occupied, and many comparatively new erections are seen among the large number of totem poles, which indicated that the inhabitants are not entirely free of their primitive ideas. The Indians at the time of my visit were about fifty in number. They appear very independent and seem to have a dislike for foreign visitors. I have learned that this community has a vague notion of distrust and suspicion of persons with modern education, especially those who show some sign of authority, and they usually suspect such a person of being an agent of the government for which they show no little dislike.

Image Number: 14964

The indifference of this community toward the immediate change of primitive habits for the modern ways which are so prominent among the coast tribes, may have been occasioned, according to the general feeling, by an agitation with regard to title to lands of the province. Some of the older men talked over this land question to me and on one occasion one of the leaders showed me a map, cleverly drawn with pen and black ink on a sheet of wrapping paper, indicating the tract of land which the chief claimed had been theirs from time immemorial. He stated that his ancestors had fought hard to retain this possession, and that every member of the group is taught at childhood to hold on to it. I could not obtain the drawing which I thought would offer a good sample of an Indian idea of map making but I photographed it. This is the first group of Indians I have ever met in the Northwest who foresaw the value of land and who are making efforts to provide some kind of a foothold on behalf of the generation to come.

The chief told me that before Git-wentl-qool was founded his forefathers were forced from the Naas River direction further into the interior, during one of the wars over the land which they now claim, and were compelled to build a fortified town which in later years was named Git-inyewo and which is now non-existent. This was located on a high hill, about nine miles north of the present town.

The people in this community appear to have fixed habits and their wanderings, until very recently, were in the nature of temporary excursions to established points resorted to from time almost unknown. On the day following my arrival some hunters came down from the neighboring mountains with fresh goat meat which was prepared in one of the houses. While the Indians were attending this feast I had an opportunity of making some photographs of the old section of the town which is strictly prohibited, as I was informed by my host.

I regretted that I came to this place rather unprepared to allow myself a sufficient length of time in which to make a closer study of the people. One should equip himself, on such side trip, with a ten ounce duck tent, some wool and canvas blankets, some provision of food, a reliable rifle, a kodak equipped with fast lenses, and, above all, some kind of protection against mosquitoes. I must say that it is not always comfortable to sleep in somebody else’s bedclothing, especially in places where insects claim just as much liberty to be at large as any other species of inhabitants.

After my return from Git-wentl-qool I spent about four more days in Git-wen-geh, during which I made a brief study of the religion, ceremonials and mythology of the people. Some notes were taken, and during the progress of my investigations photographs were procured whenever opportunity occurred. The community has some ethnological objects to offer, but most of these are rather common. From the different family collections I picked out only those that I thought might be shown as samples of things obtainable at the present time.

Old Towns Near Hazelton

From Git-wen-geh I traveled through to Hazelton, a town built by Canadian settlers on the north shore and about 176 miles up the Skeena River, passing by, for the time being, some old native villages that I intended to visit. I decided to take in the interior places first, because the early morning dews by then were no longer dripping but appearing on the bushes like cold wax, which was a sign to me that snow was not far away. If overtaken by this I knew that it would be far from pleasant to be plodding around on the Git-kshen tennis racket like snowshoes. The contrivances used by the people through this region seem to show no improvement over the crude style used by some of the wandering tribes in the interior of Chilkat.

It was late in the night when the train pulled in at the station, about a mile up hill from town. There were conveyances operated between the station and the town, to which I transferred my baggage and rode in. On the following morning I took in the surrounding Indian settlements. Along the side and on the plateau of the hill in the rear are situated log and rustic dwellings of the Indians, and at the upstream end of the new settlement is still to be seen the old native town of Git-enmaksh “Man of torch fisher” (the inhabitants in former times employed a scheme to catch a certain kind of fish in the night by aid of torchlights, from which the town took its name). There were a few old totem poles standing in the foreground of some of the native style houses and some stumps of those had fallen to decay, testifying that this town is of great age. Although it is known that there are some members of the tribe living with those of the interior, this apparently is the last town of Git-kshen proper. Comparing notations made of the pronunciation of some words with those noted among the groups inhabiting the places about the center of the region, the ancestral speech shows many variations. Likewise the habits of the people about here seem to tend in a direction almost opposite that of those near the coast.

Image Number: 14970

From Hazelton, government roads leading to various new settlements offer an easy access to the Indian towns located at different ranges in the neighborhood. One may use a saddle-horse to reach most of the many settlements or during the dry season a horse and buggy, obtainable in town, could be employed on visits to the nearer Indian villages.

About seven or eight miles east of Hazelton is the old Indian town of Hegul-git “Ostentatious man,” situated on the bank of Kshen-doo “Water overflow” or Bulkley River. The very old village is still to be seen, built on a ledge in the bottom of a bowl-shaped formation of high cliffs. It could be easily detected from the plateau on the opposite side by the weather beaten totem poles that are towering in the foreground of the wreckage of old fashioned Indian houses. On the plateau of the steep cliff back of the old village is a comparatively new settlement of the Indians who had, till recently, occupied the abandoned old houses.

Hegul-git “Ostentatious man” is a term applied by Git-kshen to the people who emigrated here from the interior, because they appeared to have much pride in the gaudy things of their attire, and it is from this term the town took its name. I was told that when they are all at home the Indians in this community number about two hundred. It is stated that the Hegul-git formerly had lived in a village called Eh-tzo-lesh-co, “At-canyon,” which was located by a canyon near where Morricetown now is, and that they moved and found the present village because of the caving in of the canyon which caused much change in their fishing grounds. It is also stated that originally this people belonged to Git-shi-genish “Wandering-man” (a term applied to the Athapascan stock on the interior of British Columbia), and that up to the time they made the move closer to the Git-kshen region, their language was undisturbed and retained its original construction. In later years, however, as was to be expected, from the early period of their occupancy within an easy access to the Git-kshen, some relations were established between the two stocks. These, few in number, were thrown together and between them is developed an intertribal language.

Even though the Git-kshen language at this end is well under the influence of that spoken in the interior, the majority of its words appear to be of the ancestral speech. By considering briefly the physical characteristics, manners and the hazy affinities of languages of this people I got an idea that future and more critical study will result in showing the tribal identity of some of these families. The attempt which I made to classify them, with the very limited amount of material, has only given rise to confusion.

Origin Of The Fireweed Clan

While at Hazelton I visited Gish-ba-yekosh “Refugee lurk” or Kisbayeksh as it is now called, another old Indian town, situated on the west shore, and about 190 miles up the Skeena River. Gish-ba-yekosh is a modification of an old name, “Ensh-baw-yeho “Where refugees hide,” derived from an incident known among the people here to be a fact, that at one time a war party came across country from the Naas and destroyed the ancestors of the present inhabitants while they lived in a town called Eh-tzo-lesh-co “At canyon” which was located at an outlet of a canyon a short distance north of the present settlement. Only one woman escaped and she took refuge among the tall growth of fireweed which happened to be the only shelter to be had in the open space. While the woman was still in a helpless condition, believing that the merciless Naasman was lying in wait for her, a stranger, a hunter, of some interior tribe came to her rescue. During the still of a dark night he took her in to the thick of the neighboring forest where they were concealed until the place was clear of all danger. It turned out that the two found interest in each other and finally became man and wife. The offspring of this union were very prolific and in course of time they spread through various divisions. They thereafter were known as the Fireweed clan, adopting as the main crest the same plant which saved the mother of the stock. The first group of this division was formed on the same spot where their traditional mother took refuge. It is stated that in later years the Owl party which, previous to the destruction of Eh-tzo-lesh-co, had been one of the main parties of the place, gradually made their return to join the Fireweed party in their new town. As time went on the Owl party secured once more the control which their ancestors had during Eh-tzo-lesh-co days and to this day are recognized as the main party of Gish-ba-yekosh. At the time I was there it is said that when they are all at their homes the Indians in the community number about two hundred and thirty.

Kisbayeksh is not very far behind some of the coast Indian towns in adopting the modern ideas. In spite of the inconveniences caused by being out of the way of easy importation of things, modern developments in many lines are noticeable in the community.

The End of the Journey

On the thirteenth of October I arrived in Skeena Crossing, one of the railroad stations, on my way back to the coast. Near the station is a small inn offering accommodations to the weary traveler, and here I decided to spend a day or two. About two miles downstream from the inn is located Git-dze-gukla “Man of precipice” or Kitsigukla as it is now called, an old Git-kshen town. Its name, evidently, is derived from the steep cliff which forms a wall on the rear side of the old section of the town. Like their tribesmen of many other communities in the region, the few remaining inhabitants, numbering about seventy, are building modern rustic dwellings on the clearings made on the top of the hill. I was told that some of the families of this place had recently moved downstream about six miles, to a village named Endimol and those holding on to the old homes are mostly aged persons. Although Git-dze-gukla is said to be very old, I noticed that most of the totem poles standing in nearly every available space through the old section appeared to be rather of recent make. The Owl crest seems to be prominent among the records shown on these poles, which testifies that it was this division which was responsible for placing Git-dze-gukla among the important places mentioned in Git-kshen mythology.

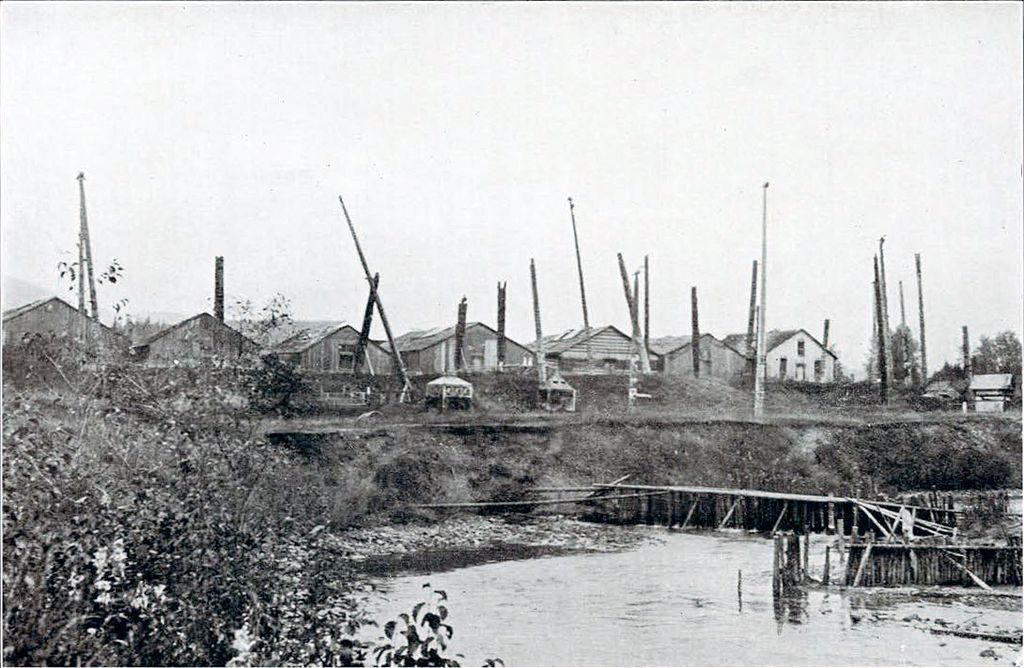

From Skeena Crossing I went through to the coast and upon my return to Prince Rupert I was a day too late to catch the weekly northbound steamer on which I had planned to make my return to Alaska. I had then but a few more days at my disposal and I thought it advisable to devote these to some nearby Indian settlements. The following day found me at Shbak-shuat “Autumn tryst,” an Indian town, situated on the south side at the lower end of Skeena River, which is now called Port Essington. About half of the place is occupied by salmon canneries which, together with the Indian section, appeared to be entirely abandoned. The reader will remember that the time of my visit here was in the autumn, the season during which the Git-kshen of former times had paddled together to this place for the final hunts in the salt water, from which the old meeting point had taken its name, but much change has taken place since those days. The old fashioned slow canoes have now made way for the speedy motor boats on which the Tsimshian of today rush to the modem town of Prince Rupert where the attractively arranged show windows offer to him his choice of winter supplies. Shbak-shuat is no longer popular at this season.

L.S.