The Director spent the summer of 1919 abroad in the interest of the Museum. After visiting London and Paris he proceeded to Egypt and afterwards to Palestine and Syria. In Egypt he spent a part of the time at his disposal at the camp of the Eckley B. Coxe Jr. Expedition at Memphis, which, under Mr. Fisher’s direction, was excavating the Palace of Merenptah from 1915. These excavations have now been resumed after an interval of a year. In Cairo the Director was successful in securing for the Museum some unusual examples of early Arabic art, consisting of tiles, woodwork and mosaic as well as a collection of the highly interesting pottery found at the ruins of Fostat, the predecessor of Cairo and the earliest city built by the Arabs in Egypt, founded in 641 A.D. During an inspection of this site, together with Ali Bey Bahgat, Director of the Arabic Museum in Cairo, Dr. Gordon was able to see the conditions under which the pottery is found and satisfy himself as to its relation to the history of ceramic art in the Near East.

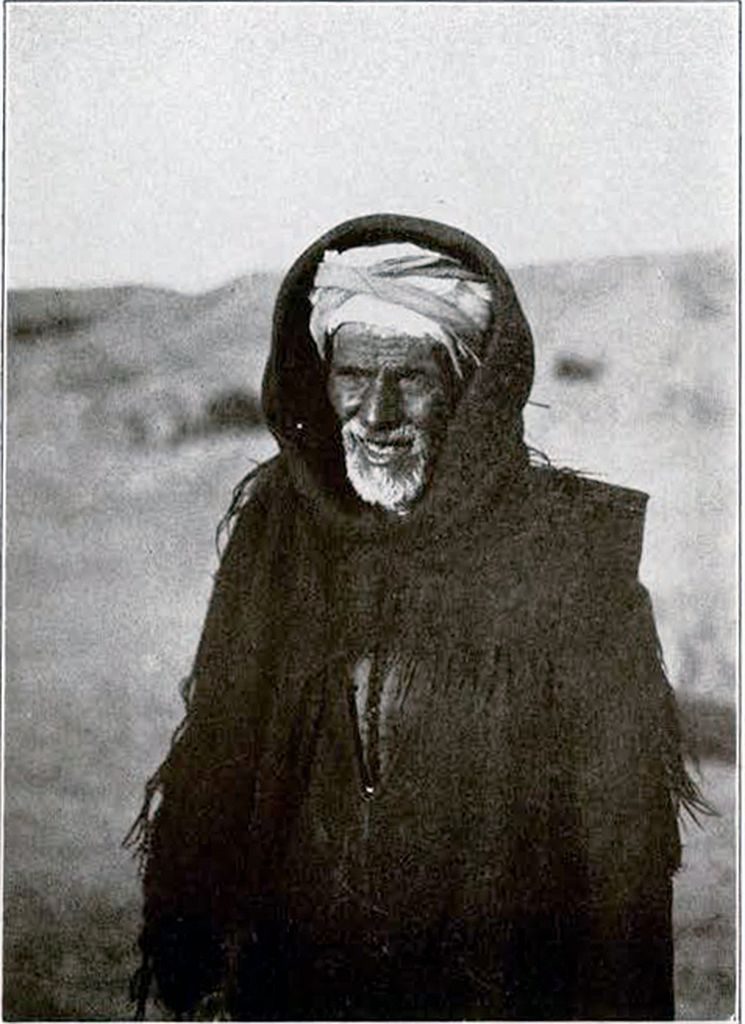

Mr. Fisher, Curator of the Egyptian Section, in charge of the work in Egypt, and Mr. Alexander Spanakidis, of the staff of the Egyptian Expedition, accompanied the Director on the journey through Palestine and Syria. The main object of this journey was to take note of the present conditions surrounding the ancient ruins and other evidences of past civilizations which in these countries await investigation. The places of interest to archæologists may be divided into two groups for purposes of future study; those that before the war had been subjected to systematic and partial excavations, like Samaria and Megiddo, and those that have not been excavated at all, like Beisan and many other places of historic importance, closely associated with one or other of the civilizations that, in passing, have left their mark on the Holy Land and the country adjacent to it on the north.

The Army of Occupation has respected all ancient sites, and monuments and ruins of every kind remain uninjured by the war. Every precaution has been taken to secure their safety and protection. With the object of preserving intact all the ancient places until the territories have come under permanent control with a definite political status, the authorities now in charge of Palestine and Syria have impartially forbidden all digging of antiquities pending the decision of the allied and associated powers. They propose that in the final settlement of political issues the archæological claims of Palestine and Syria shall be defined and adjusted to local conditions. It is believed that excavations may then be conducted under rules that will give adequate protection to all interests involved. The ancient history of Palestine is a subject that has a special interest for the whole world and it may be expected that, with new opportunities, well planned and exhaustive investigations will be undertaken by learned societies in Europe and America.

In Mesopotamia many known mounds that mark the sites of ancient cities await excavation. Other cities mentioned in the ancient writings remain to be discovered or identified. This work will occupy many years, generations of trained archaeologists will be occupied with these interesting tasks, and for generations to come philologists will be interpreting recovered records and reconstructing the earlier history of civilization. The present moment is a favorable one for undertaking the excavation of the ancient cities of Mesopotamia. If the agencies that make for peaceful and orderly conditions remain in control, the next few years will witness some progress in these excavations. We may hope also for an era of peace and prosperity for the lands where the earlier civilizations had their home.

Image Number: 32689

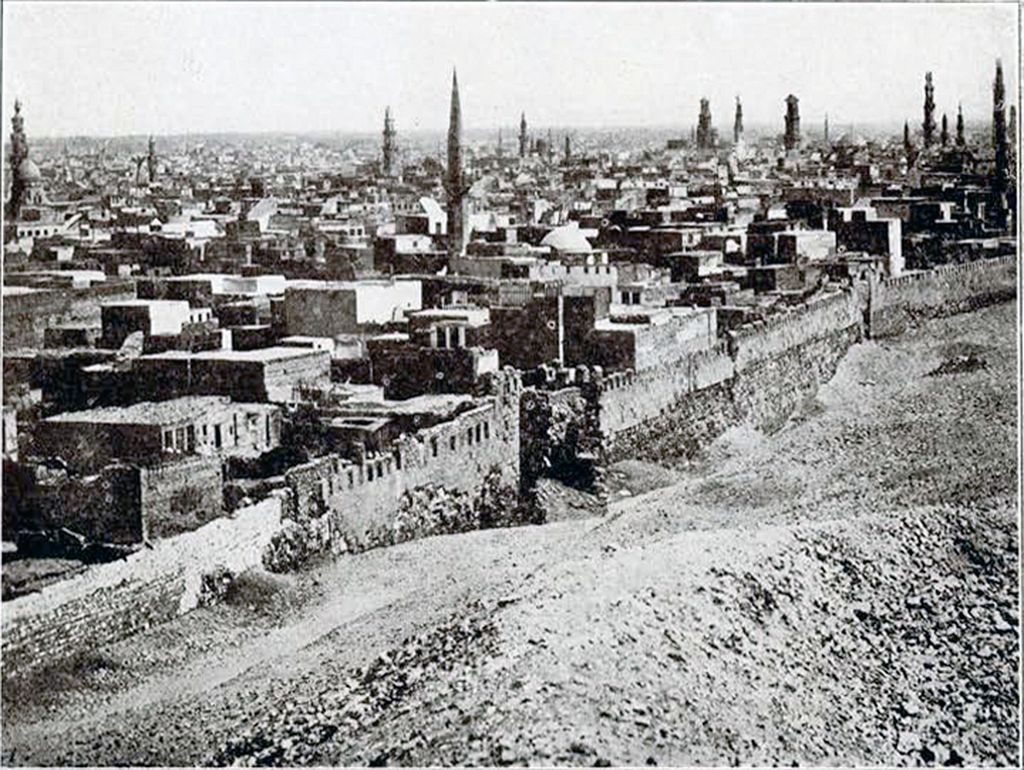

The citadel of Cairo (El Kala) stands on a spur of the Mokattam hills and occupies the south eastern corner of the city. It was built by Saladin about A.D. 1166 and is a fine example of Arabic Military Architecture. The alabaster mosque with its two slender pointed minarets was built by Mehamet Ali (1805-1848). Its dome and slender pointed minarets, rising above the city, can be seen from the distance with very fine effect. The view from the ramparts of the cidatel is one of the finest and most picturesque in the world. Below is spread the city, with its ancient walls and towered gates, its hundreds of mosques surmounted by dome and minaret; its gardens, palaces and squares, the valley of the Nile with its palm groves; the Nile itself, most majestic river in the world; the pyramids on the horizon to the West, and on the East the stark cliffs that fringe the desert.

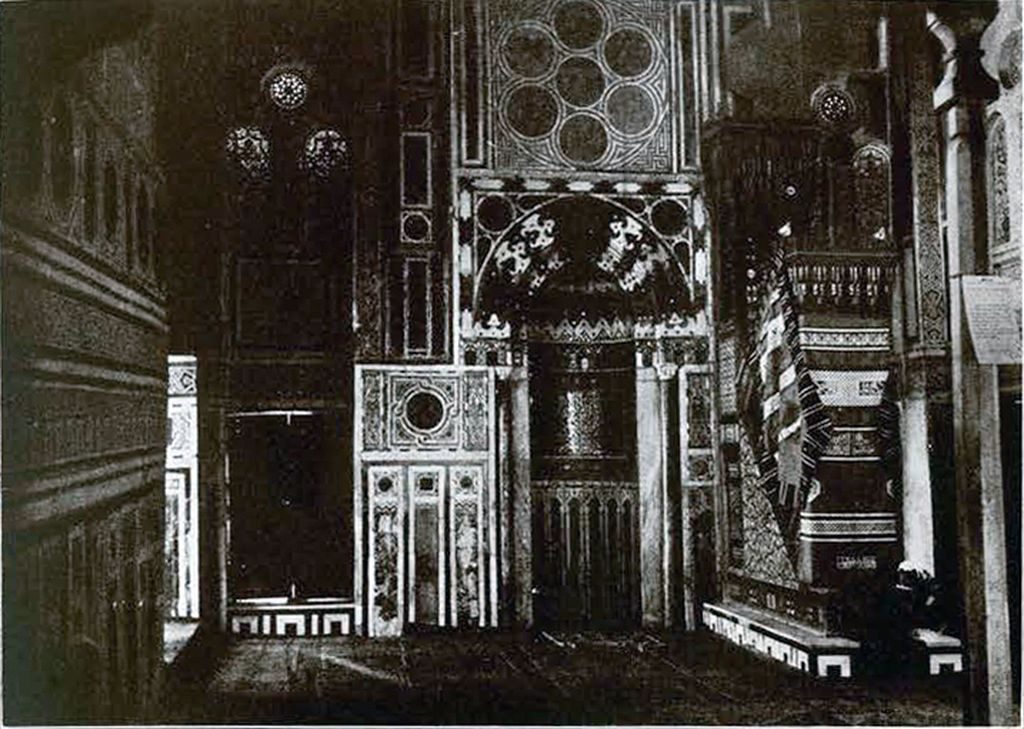

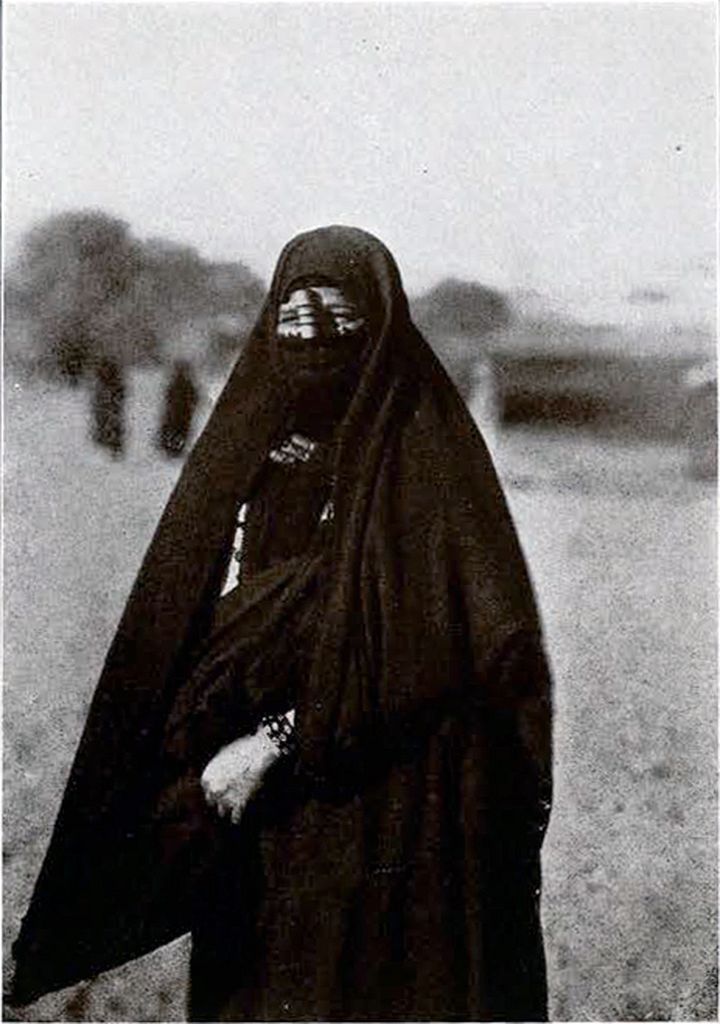

In 641 A.D. the Arabs under ‘AMR-IBN-EL-ASS conquered Egypt for Caliph Omar, who, ruling the Arab world from Medina, was transforming Islam from a Religious Sect to an Imperial System of Government. The Roman Garrison capitulated and where ‘Amr pitched his tent in the open country a City grew. It was called El-Fostat (The Tent). The ruins of this first Arab Capital to the south of Cairo are now being excavated. In 969 Egypt was conquered by Jauhar for the Fatimite Caliphs. Where Jauhar pitched his tent a new city grew called El-Kehira (The Victorious), a name which has became transformed into Cairo. It is the greatest and finest of all Arab cities and in its gates, houses and mosques, dating from the tenth to the nineteenth century, may be read the history of Arabic Art from its beginnings, through its mature development and its decline.

The east side of Cairo is divided into many quarters with narrow winding streets. The shops are small and open in front. The Mohammedan quarters take their names from the occupations of the inhabitants or from some prominent building. Besides these there are the Jewish, Coptic and “Frankish” quarters. In the latter, since the days of Saladin, the European merchants carried on their trade. At the present time some of the principal European shops are found in the Muski, the principal street of the Frankish quarter.

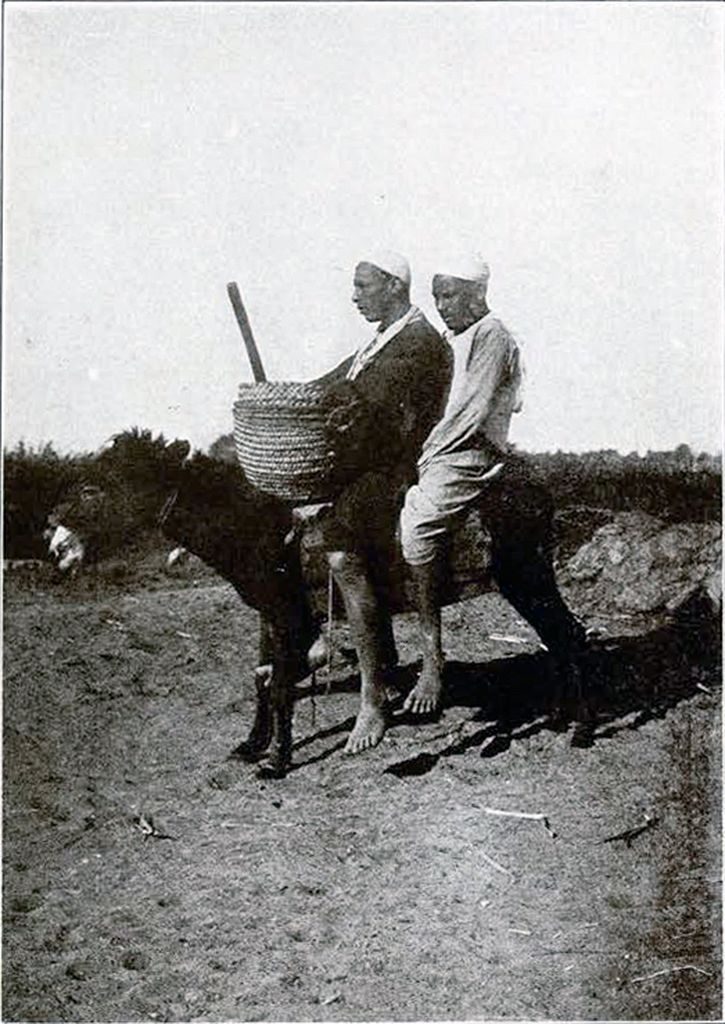

From the west bank of the Nile a raised causeway runs to the pyramids of Gizeh. It is shaded by a double row of trees and during the harvest season it divides broad and fertile fields carefully cultivated. When the river is high these fields are flooded and the road divides a broad stretch of muddy waters that fertilize the soil. The pyramids rise on a platform of rock on the edge of the desert.

The date palm has been cultivated in the Nile and Euphrates Valleys from the most ancient times. On Assyrian tablets its cultivation and use are described, and throughout the whole history of Arabia, as at the present day, it formed the staple article of diet and the chief source of wealth. The fresh ripe fruit, which has little resemblance to the preserved dates of commerce, is well worthy of the tributes that the Arabic poets have bestowed upon it from time immemorial.

Image Number: 32685

The date palm is the pride of the Arab for it is nature’s greatest gift to his race. If an Arab plants a date palm on another man’s land the tree and its fruit belong to the man who planted it. Likewise if he plants it on the public domain. It is a graceful tree 60 to 80 feet high and its home is across Northern Africa and Arabia to India. Along the Nile are to be seen great groves of date palms as well as little clumps or single trees. Sometimes several owners have shares in one tree.

Image Number: 212577

On the ancient Egyptian monuments are seen pictures of Nile boats propelled by sails and oars. From time immemorial the commerce of the earliest civilization in the world was carried up and down the Nile and along the eastern shores of the Mediterranean in boats not unlike the feluccas that make one of the most picturesque features of the Nile today. Life, movement, trade, intercourse, are all suggested by these busy and heavily laden barks, dropping down with the current or beating up from the Mediterranean to the far reaches of the Nile.

The felucca forms a link with the past. Navigation on the Nile today is partly by steamer, but steam will not soon replace the shipping that was ancient when Joseph went down to Egypt and that has held its own for more than six thousand years. Wood has always been scarce in Egypt and it will be seen that the hulls of these vessels, both the ribs and the plankings are built of many small pieces fitted together. An ancient boat dug up from the Nile mud was built in the same manner and on the same lines.

Entrance to an Arab house in an old quarter of the City. The carved wooden doors occupy a niche of masonry built into a wall of rough stonework covered with plaster. This masonry, in the form of a pointed arch, is adorned with the most intricate patterns traced with the chisel in a style called Arabesque. The Arabs have given the world a style of domestic architecture and a wonderful body of decorative art, that together give life in the East an appearance of rich magnificence that has never been equaled in the West.

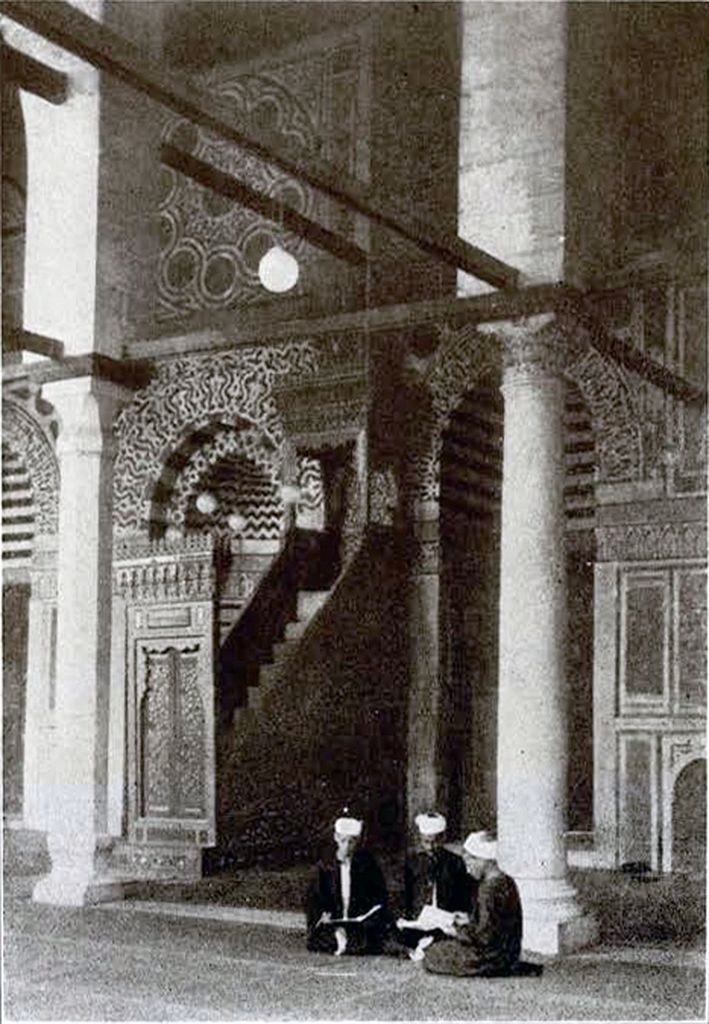

The motif that reveals itself in every mosque, and that distinguishes this style of architecture, is founded on the Moslem faith and teaching. The outlines of the building, the details of construction and the design of the interior proceed alike from the same incentive. No representation of anything in nature may be used and therefore the decoration must follow a line of development in which the entire elimination of natural forms brings it into striking contrast with the religious art of the Christian world.

On the east of Cairo are the tombs of the Mamelukes, often mistakenly called the tombs of the Caliphs. The successors of Saladin surrounded their court at Cairo with Turkish slaves called Mamelukes. These retainers quickly displaced the ruling family themselves usurped the supreme power, founding a line of Sultans (1250). The tombs that these Mameluke Sultans of Egypt made for themselves, though they have suffered from neglect, are fine examples of Arabic architecture.

Image Number: 32708

Image Number: 32708

The water of the Nile, though holding in suspension much mud from the mountains of Abyssinia, when allowed to stand, becomes clear and wholesome. The women with their water jars is one of the characteristic sights on the Nile banks. The fellaheen or peasants all live in villages surrounded by the fields which they cultivate. These villages are on the banks of the river or else on the canals which the government maintains for irrigation.

Image Number: 32727

Image Number: 32727

In the Egyptian Museum in Cairo is a wonderful collection of the art of ancient Egypt, including furniture found in Royal Tombs. The chairs shown in the picture are of wood, carved, painted and gilt. In the amazing halls of this Museum may be seen how the Egyptians lived during four thousand years. Their works show explicitly how the marvelous civilization of the Nile Valley grew up in ancient times, flourished and decayed. There are halls of statuary, halls of painted reliefs and inscriptions, rooms of jewelry, cases of papyri, embroidered vestments, musical instruments and every form of utensil, all wonderfully preserved from the oldest civilization in the world.