Considering the enormous wealth of decorative material to be found in prehistoric Peruvian art it is strange more frequent use has not been made of this interesting and original type of design by the artist, designer and manufacturer.

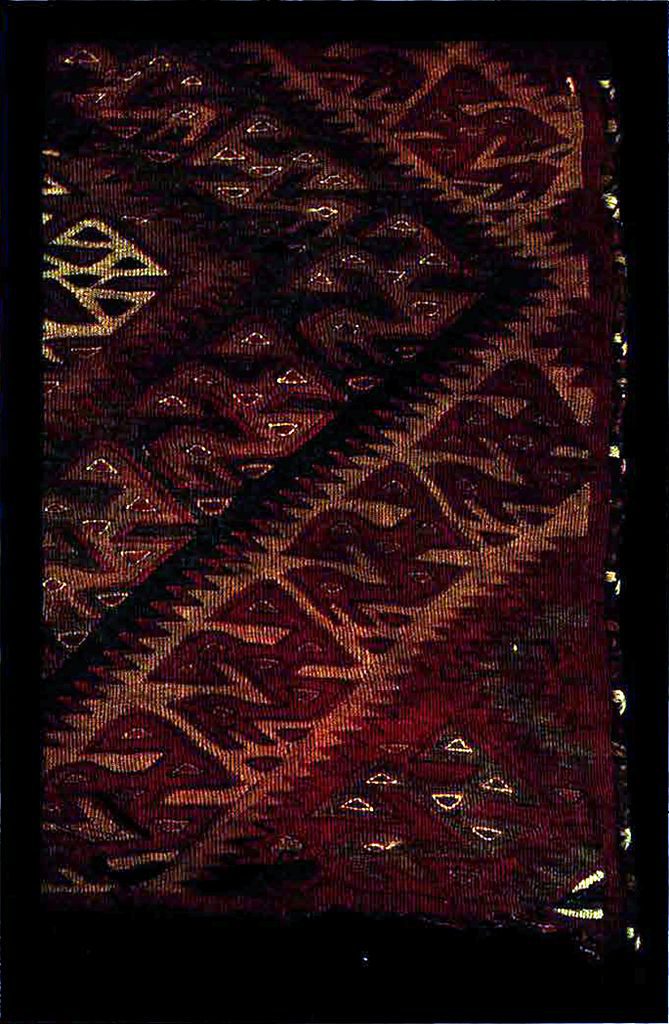

In the possession of the University Museum are collections of ancient textiles from the Pachacamac cemeteries, and elsewhere in Peru which for richness of color, beauty of design and technical skill are equal to any of the oriental fabrics, and quite out distance our own modern productions.

We know the Peruvian civilization had attained a very high artistic development before the Incas inhabited the country. Therefore in all probability some of our earliest specimens may have been products of the socalled Megalithic peoples.

They were all found in prehistoric graves, many still around the mummies, and the fact that the cemeteries were on the edge of the desert, where rain is practically unknown, accounts for their marvelous preservation.

The most realistic art in ancient Peru, one student of textiles attributes to an older culture called the Chimu, and the Incas at the time of the conquest were still producing very beautiful fabrics, showing they had not lost the traditions of the earlier civilization.

The Peruvian was unusually skilled in manipulating his simple hand loom where the weaver produces the design as the material grows, much in the same manner as the weaving of oriental rugs. In addition to fine cotton and wool cloth we have brocade, embroidery the socalled “double weaving” and tapestry. In tapestry Peru reached its highest development, placing this kind of texture in a class by itself—making the Gobelin and even the Chinese silk tapestry appear coarse and heavy in comparison. Some of the finest pieces contain nearly three hundred weft yarns to the inch and their cleverness in adapting most intricate design and overcoming the technical difficulties of the loom is something that has never been accomplished by any other people—excepting perhaps the makers of the Coptic fabrics from Egypt, dating from the first centuries of the Christian era. In many ways the likeness is indeed remarkable between these two ancient lands, half a world apart.

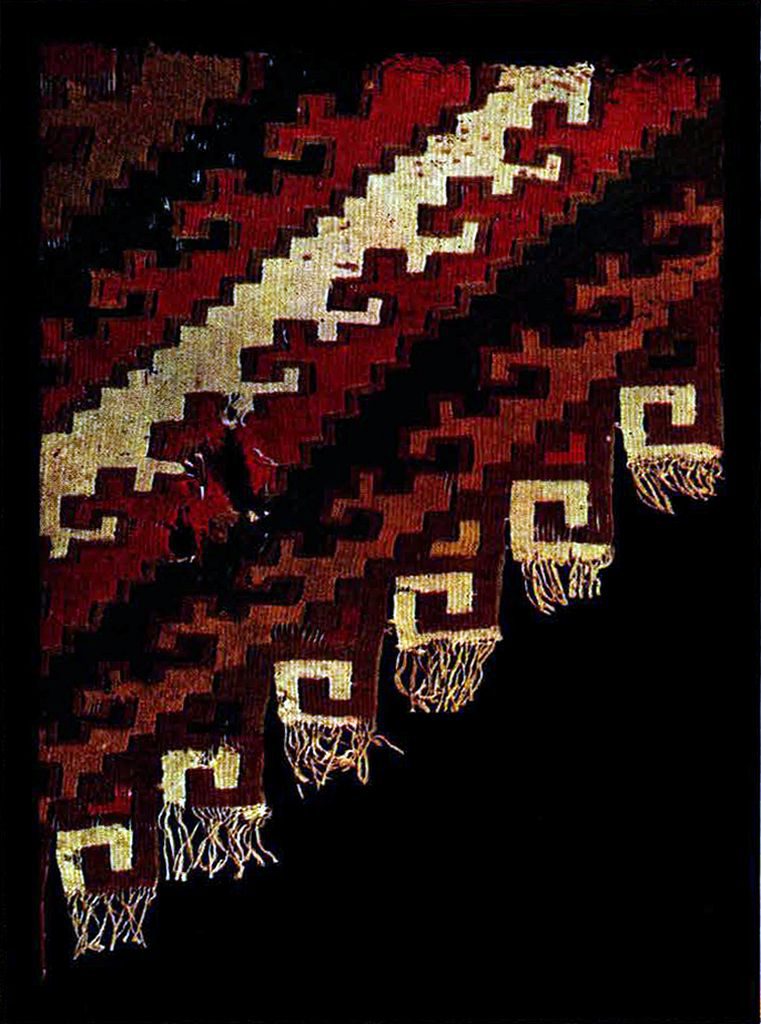

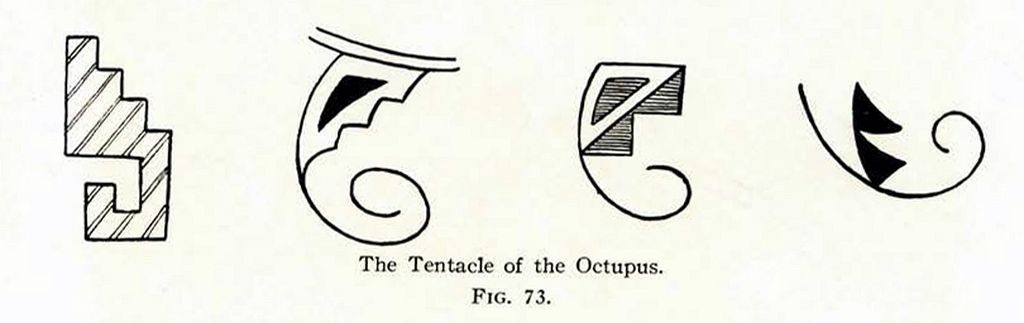

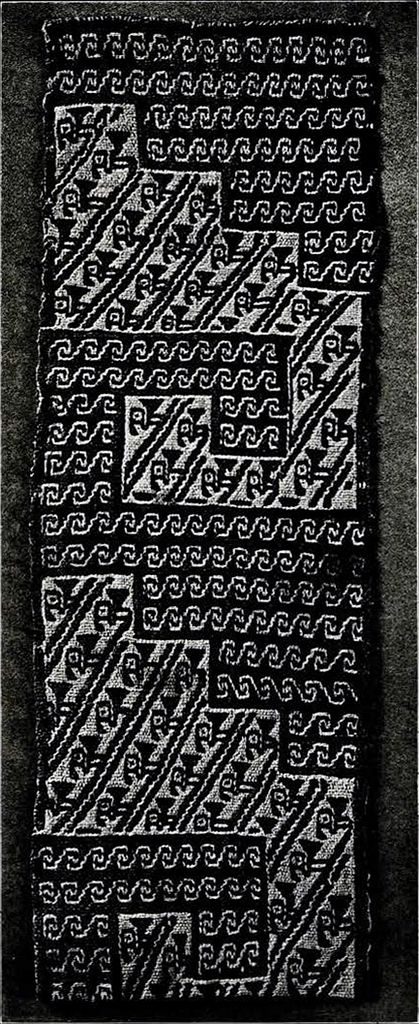

Like most historic peoples the Peruvians made use of the objects which were familiar to them in their daily life. First we have the realistic forms. Then little by little through repetition and elimination we get a conventionalized or geometric figure which is far removed from its original source of inspiration. Fig. 77 is a good illustration of this, beside being a very clever piece of inverted design representing the tentacle of the cuttlefish. We find the same motive in other forms in embroidery and on pottery.

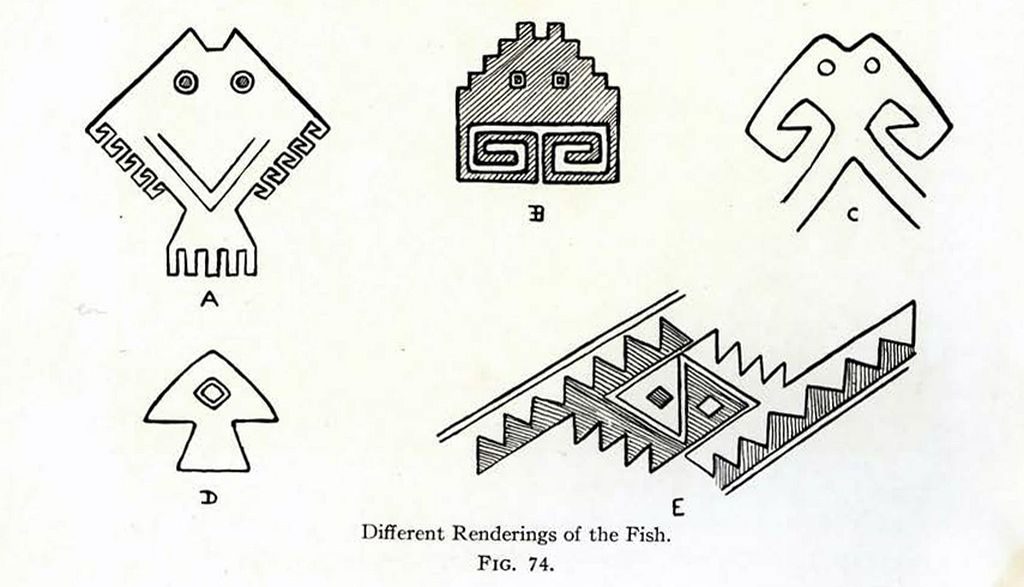

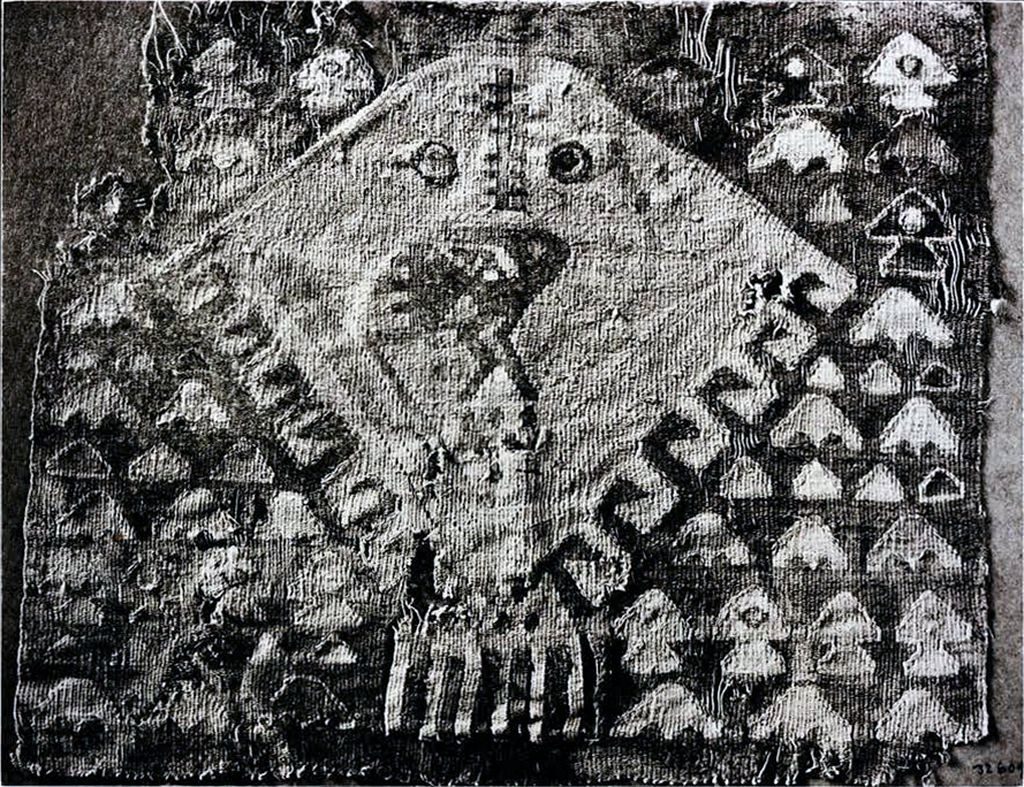

Notwithstanding the enormous variety of design in these quaint animal, human and geometric forms there are in reality only four or five subjects used, the man, the fish, bird and puma or cat, the same recurring singly or joined in every conceivable combination.

The Peruvians of the coast region worshiped the sea and the fish being a natural emblem of the sea, we find it with more frequency than any other motive in all their arts.

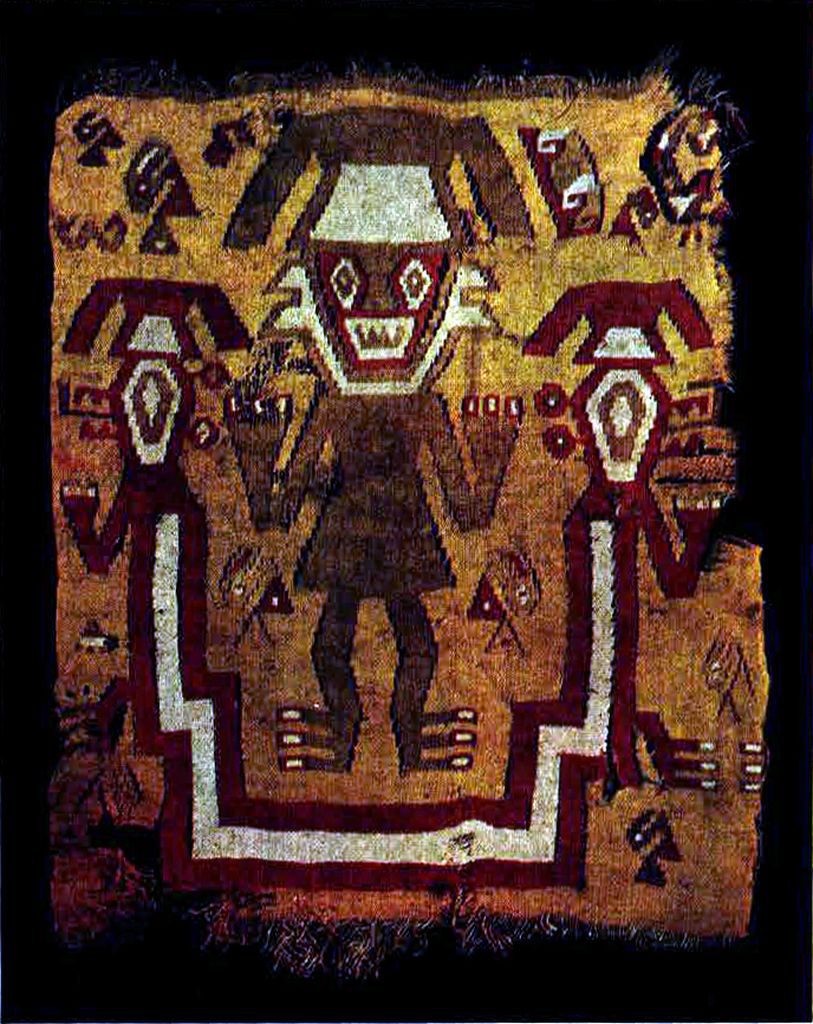

In the center of Fig. 78 we have a very realistic skate, surrounded by much conventionalized little fishes and fish heads.

The character of the material is of first importance and influences the design. As the difficulties of the loom had to be considered, the tendency for curves to become rectangular is very marked.

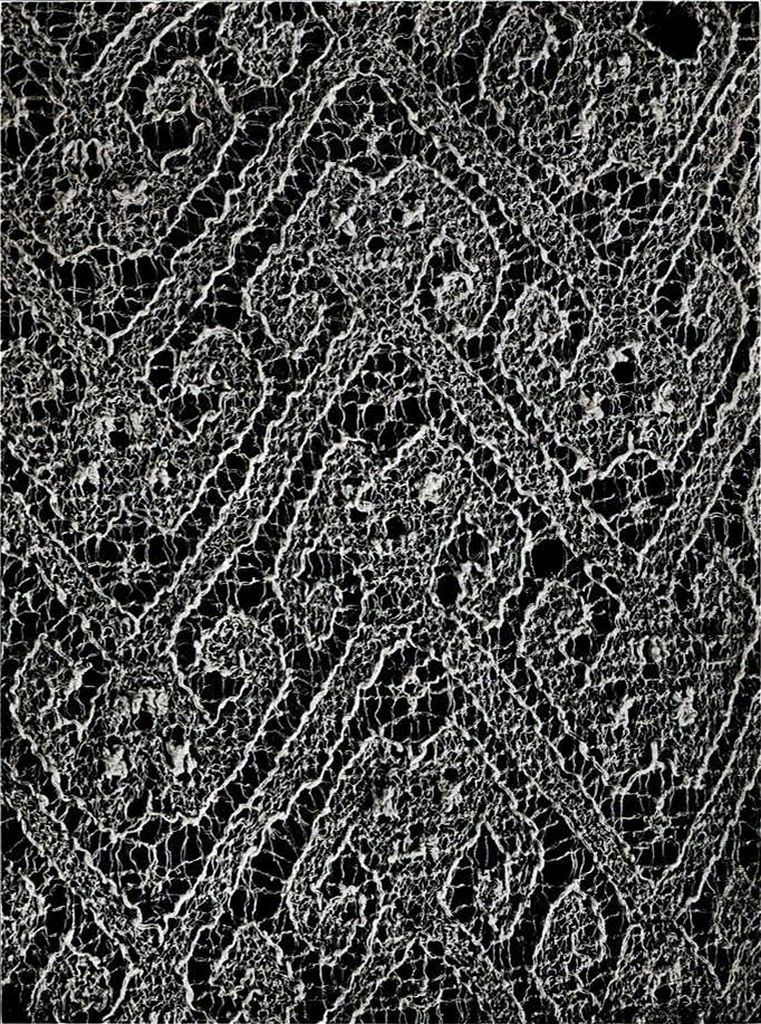

Fig. 79 is still another rendering of the fish head in an exquisite piece of lace, a form of art which is left to us by these remarkable people.

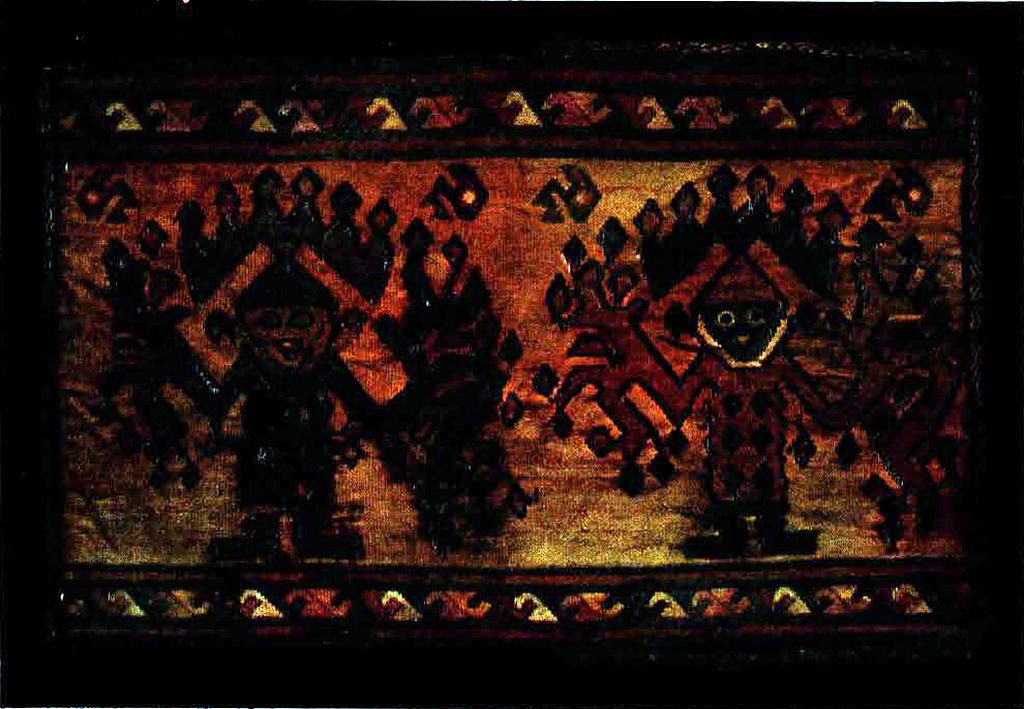

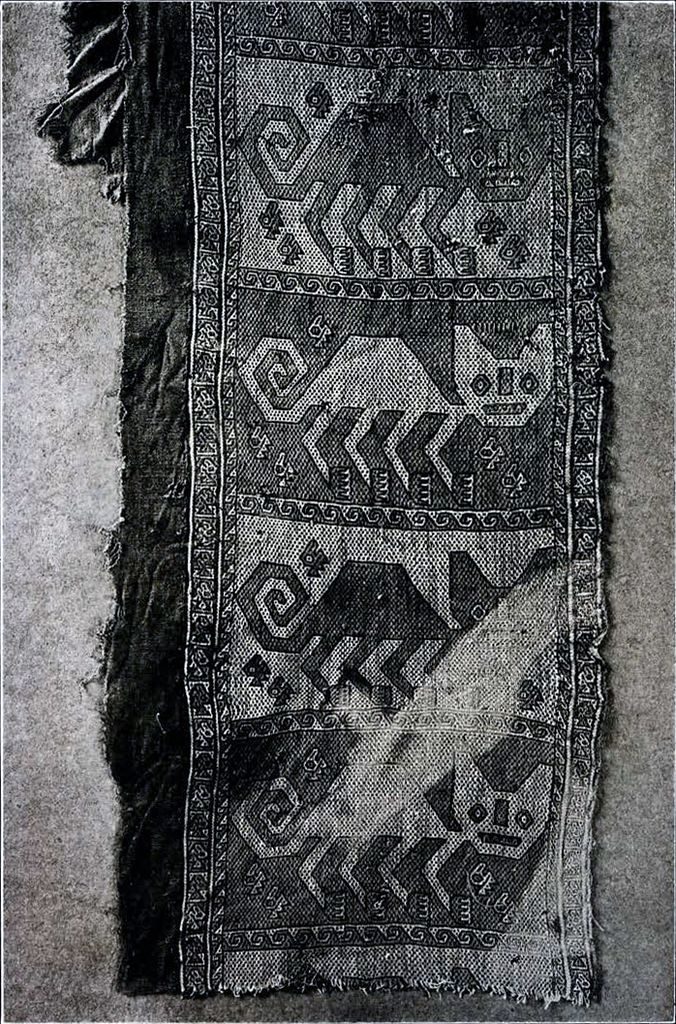

The interlocked bird in Plate I is from one of the most beautiful tapestry belts in the collection. The colors are of deep rich tones, the same on both sides; the ends of the yarn have been cut off and carefully tucked in so that it is impossible to tell the face form the reverse.

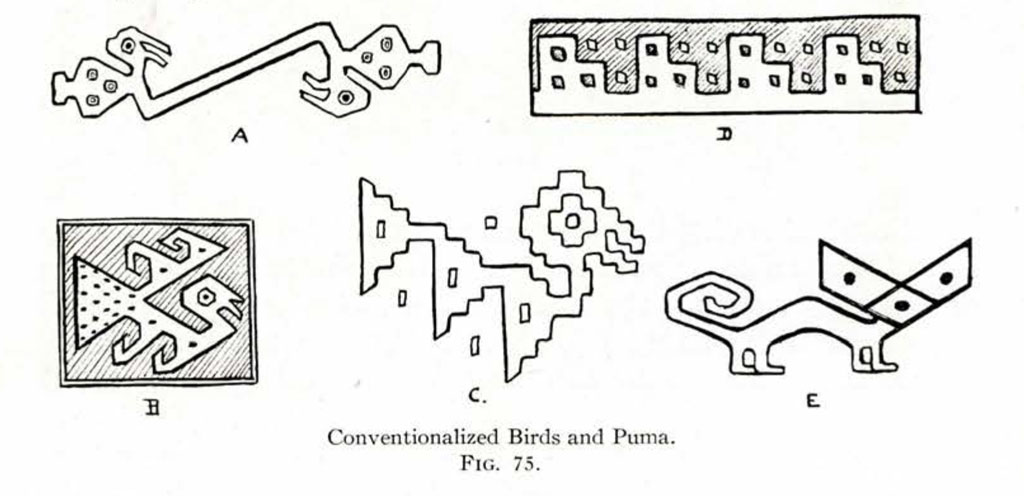

The bird in Peruvian art does not need much description as it has hardly ever lost its identity. We find it linked with the cat and fish in many forms, but it is always recognizable. The example shown in Fig. 75 A, is joined with the puma head, making a cleverly elongated design to decorate a narrow ribbon. It is repeated the entire length of the material. In the example shown in Fig. 75 B, the entire bird is used to fill up a square. The border of a loin cloth from which this was taken is made up of such squares, each bird of a different color, making it a most effective whole. See also Plate III.

Fig. 75 is interesting as showing the influence of basketry upon textiles. D and E are of course derived from the puma.

The greatest care and skill was perhaps expended upon the human figure as a motive, and upon the mythological characters. The designs in these are too ornate to be described minutely and must be seen in order that the wonderful variety of color and symbolism they portray may be appreciated.

As the ancient Peruvians have left us no literature it is through the wealth of their decorative arts that we realize the high degree of their civilization. And all this is purely American, showing no trace of outside influence. We can with profit go to these older Americans for our suggestions and inspiration.

E.E.B.

Museum Object Number: 32609

Image Number: 20580