THE Fifth Dynasty Tomb of Ra-Ka-Pou from Saqqara was sent to this country by the Egyptian Government for the St. Louis Exposition in 1904, and afterwards presented to the University Museum by the Honorable John Wanamaker. It was temporarily set up in a room in the basement, where it was shown, on application, to those who knew of its existence in the Museum, but it was only with the opening of the Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. Egyptian Wing last spring that the Museum had room to install it fittingly in the Egyptian galleries, where it is now one of the popular features of the collections.

The tomb, a typical mastaba of the Old Empire, was first noticed and briefly described by Mariette in Les Mastabas de l’Ancien Empire, 1891, where he copied the inscriptions of some eighty-six of the hundred and forty tombs discovered by him at Saqqara in 1877. He thus describes that important cemetery of ancient Memphis:

The Necropolis of Saqqara

“The most ancient, most extensive, and most important of the necropoles of Memphis is the one to which the village of Saqqarah has given its name. . . .

“Just at the point where the desert begins and cultivation ends, is a sandy plateau, which, from a height of forty meters, dominates the verdant plain stretched at its base. On the top of this plateau lies the necropolis.

“The necropolis of Saqqarah must once have been, like all Egyptian necropoles, a veritable city of the dead. There twelve pyramids rise, drawing the attention of the traveller to it from afar. It has its streets bordered by monumental tombs, its districts, its thoroughfares, its squares. There may be seen enclosures where they stored and where they worked the stones, and other enclosures where they penned the animals destined to be sacrificed during the funeral ceremonies.

“The necropolis of Saqqarah must have had, like all Egyptian necropoles, its officials and its employes, charged with the care of the tombs, with their upkeep, with the distribution of the lots assigned to families, as well as the ceremonies in connection with the funerals and the cult of the dead. The inscriptions discovered during the exploration of the necropolis are unfortunately extremely poor. . . . The study of the place, supported by the study of the papyri, informs us satisfactorily upon the extent of the necropolis and its general disposition; we are less fortunate in regard to the personnel, necessarily quite numerous, that must have functioned there.”

Museum Object Number: E15729

In the necropolis Mariette found several different kinds of burials. The poor were simply laid in the sand at about a meter’s depth, or in crudely built brick vaults, or in the large communal tombs where mummies were stacked, one above the other, by the hundreds.

The tombs of the mastaba type have been found only in the cemeteries of Memphis, and all belong to the period of the Old Empire (about 2500 B.C.). They must have been, judging by their size and rich decorations, the tombs of the wealthy citizens of Memphis during the Pyramid Age. Ra-Ka-Pou, as we read in the inscriptions on his tomb, was an official of the court.

Concerning the name given to this type of tomb Mariette says, “they call in Arabic mastaba the bench or platform built of stone that is seen in the streets of Egyptian villages before each shop. . . . There is in the necropolis of Saqqarah a tomb which has in its gigantic proportions the form of a mastaba. The natives of the neighborhood call it Mastabat-el-Farâoum; The Seat of Pharaoh,’ believing that once a Pharaoh sat there to mete out justice.

“Now the Memphite tombs of the Old Empire which in such number cover the plateau of Saqqarah are all constructed in more or less reduced proportions on the type of Mastabat-el-Farâoum. Therefore the name of mastaba which from the beginning in the necropolis of Saqqarah we have given to this class of tomb.”

Structure of Mastaba Tombs

Briefly, the general plan of construction of the tombs is as follows: deep in the solid rock below the sand, was hewn the vault in which the mummy was to be deposited, and once buried, hidden forever from human eyes. A rectangular shaft, slanting or vertical, led from this subterranean vault to some secret spot in the mastaba, or superstructure of the tomb. When an undespoiled tomb was found, it was noticed that this shaft, masonry-lined where it traversed the sand, was filled with broken bricks, rubbish and cement, to make the only entrance to the vault impenetrable. The superstructure of the tomb might vary in size, but was always in the mastaba shape, rectangular, flat roofed, the four sides sloping slightly inwards. The core of this superstructure was of sand, gravel and rubbish, but the unornamented outside and often elaborately decorated chambers inside were faced with limestone blocks, averaging two and one half feet long, one and one half high and two deep. Not far from the chamber, and carefully hidden in the thickness of the masonry, was a rectangular recess built of large stones which has been called serdab. It was sometimes without communication of any sort with other parts of the mastaba, sometimes connected by a narrow conduit with the chamber, in order perhaps that the offering of incense might reach the soul of the deceased through his statue walled up there.

The Tomb of Ra-Ka-Pou

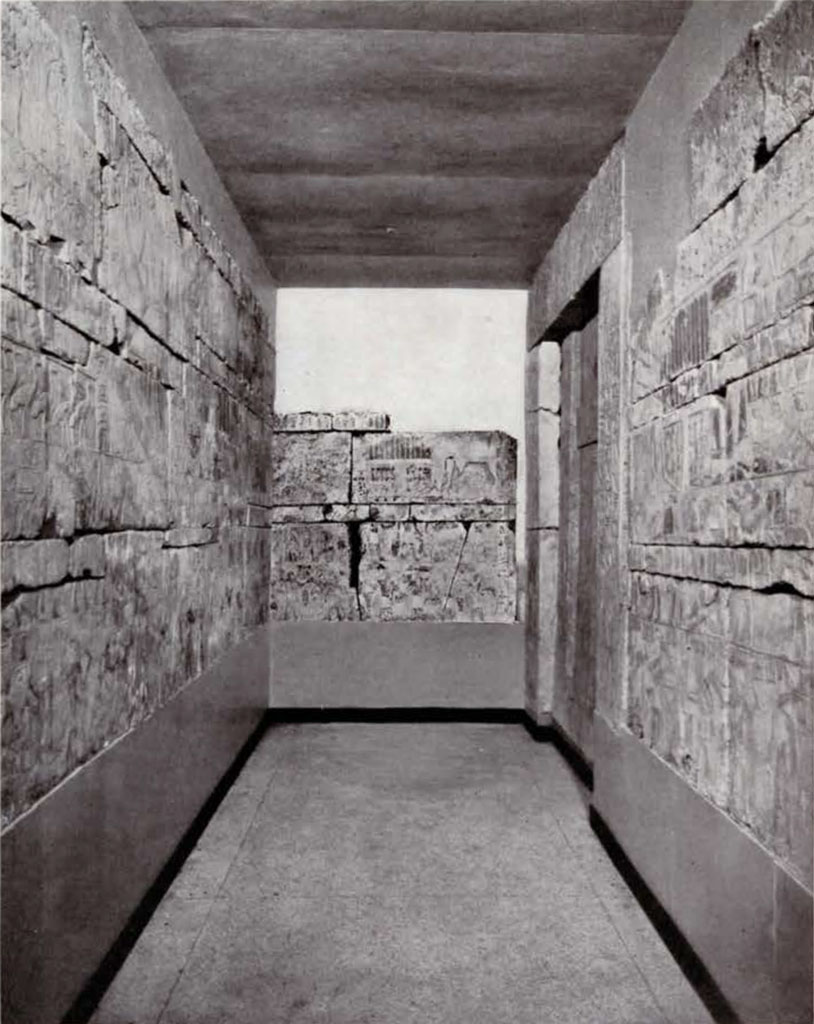

The tomb of Ra-Ka-Pou in the Museum had when Mariette visited it, the remains of two chambers approximately of the same size and shape within its massive structure. The outer room was undecorated, so that the sculptured passageway and inner room, now set up in our collections, formed the most important and interesting features of the tomb. This inner room is 19 feet by 6; the existing walls 10 feet high, the passage 3½ feet long and 2 feet wide.

Museum Object Number: E15729

Image Number: 31226, 142944, 31200-31202

As we enter the narrow passage, we seem to be passing, as the soul of Ra-Ka-Pou did on his journey to the lands of the blest, down a river, for on either side are sculptured in low relief, once brightly painted, representations of the narrow, high-sterned boats that sailed up and down the Nile five thousand years ago. On the right of the passage are three sailing vessels, on the left four propelled by oars. Models of just such boats were found in later tombs and crude pictures of similar boats appear on vases of prehistoric times, all of them very like the Arab feluccas that skim the waters of the Nile today. The oblong sail is hung from a square yard-arm at the top of the mast, and a sailor perched high on the stern holds the sheets in both hands. Two steersmen with long oars stand below him, and a man with a long pole, or boathook perhaps, stands in the bow. Along the center are seen the heads of half the crew of oarsmen, the corresponding half on the other side of the boat not being represented. The crews vary in the different boats from eighteen to twenty-six. The sailing boats on the right seem to be moving along before a good breeze, and the crews have shipped their oars, but in the rowboats on the left you see the crews throwing their weight on the long oars. In the center rowboat one of the helmsmen holds a baton in his right hand, perhaps to beat time for the rowers, while another man who may be the captain talks to the boatman in the bow.

Within the chamber the walls are sculptured from top to bottom with processions of servants carrying funeral offerings towards the great stele or false door at the end of the right hand wall. This stele, the most important feature of the tomb, represents, according to Marlette, the façade of a building of the period, i. e., the tomb itself ; a symbol of the tomb, to which the owner hopes eternal offerings will be brought just as the sculptured scenes on the walls suggest. The inscription, here beautifully cut in intaglio and painted bright blue, and the sculptured scene in the center give the key to the prime meaning of the decoration of the tomb.

Architecturally the stele represents a double doorway, or door within a door, the jambs and lintel of each being inscribed and sculptured. Below the lower architrave is the true lintel, or “drum,” inscribed merely with Ra-Ka-Pou’s name. Between the two architraves is a space filled with the scene of the offering table: Ra-Ka-Pou is seated on a chair before an offering table on which are arranged slices of bread(?). Above his head is an inscription giving his name and chief titles: “Overseer of the scribes of the treasury, assistant in the treasury, Ra-Ka-Pou,” and above and below the table a list of offerings that he wants: “A thousand loaves of bread, a thousand jars of wine (or beer), a thousand cakes, a thousand heads of beef, a thousand geese, a thousand of all sweet things, a thousand hanks of thread of every kind, a thousand rolls of cloth(?).”

On the upper architrave (i. e., the “outer door”) is the inscription that Marlette found usually on the entrance doors of the tombs, as well as on the false doors in the inner chambers:

May Anubis before the Divine Portal grant an offering,

And his (Ra-Ka-Pou’s) funeral equipment

In the Underworld, in the cemetery

To him who is deserving before the great god.

May Osiris, ruler of Busiris, grant an offering,

Sepulchral offerings ht New Year,

At the Festival of Thoth,

At the Great New Year Festival,

At the Festival of Seker,

At the festival of Great Heat,

At the Festival of Min,

At the Monthly Festival,

At the feast of the month and of the half-month,

And every festival day, in joy forever.

Overseer of the scribes of the treasury,

Assistant in the treasury of the great house (palace?),

Chief guardian of the treasury

And head priest of the altar of the pyramid of Assar.”

Assar was the eighth king of the Fifth Dynasty, which enables us to date Ra-Ka-Pou’s tomb as about 2650 B.C. At the right of this inscription is a figure of Ra-Ka-Pou standing, a staff in his right hand, and a curved object (piece of cloth?) in his left; beside him is written the title ” assistant in the treasury, Ra-Ka-Pou.” Similar inscriptions run down the jambs of both doors, at the bases of which are two seated figures of Ra-Ka-Pou similar to the one before the table of offerings, and four standing figures like the one on the upper architrave; above each is written “Ra-Ka-Pou.” The figures of Ra-Ka-Pou are worthy of notice. We see him dressed only in a short kilt, tied up in front by a girdle, the ends of which fall down to his knees. He wears a heavy close collar, a closely curled wig and a short beard. In the seated pictures the chair is carefully drawn, and we see its very low back over which falls the end of the cushion, its graceful legs in the form of those of a lion, and little red cones beneath them for added support and height.

Museum Object Number: E15729

Image Number: 31203

Before this great stele or false door was probably placed a small stone offering table, inscribed, the type of which may be seen in the Museum collections.

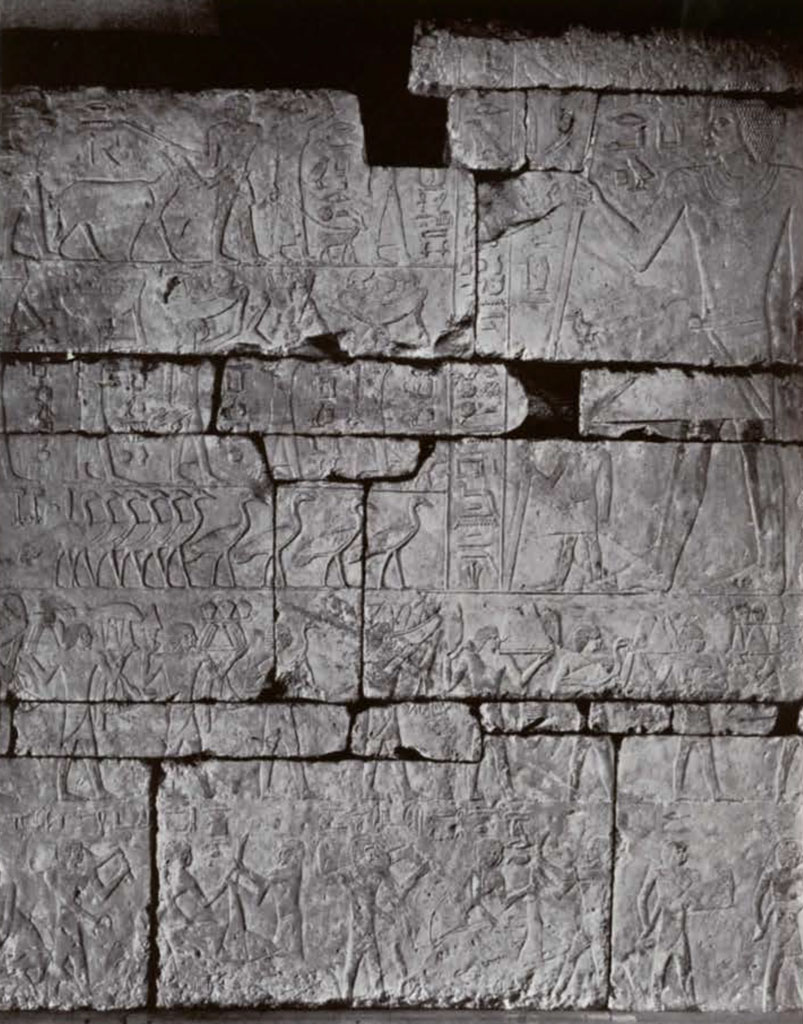

The rest of the walls bear representations of the bringing of the offerings mentioned in the great inscriptions on the false door, each wall being dominated by a colossal representation of Ra-Ka-Pou.

On the right wall, as we enter, we see this Court Official seated before an offering table, just as he appears on the center panel of the false door, except that here he carries in his left hand the threefold flail or fly whisk, a badge of office. Before him are heaped the offerings, covering three registers of the entire wall: trays piled with joints of beef, others with vegetables, or loaves of bread and cakes, trussed ducks and geese, baskets of figs, jars of wine or beer, grain, onions, calves’ heads, and many more pots and vases, the contents of which it is hard to guess. Just before his head, above the offerings, is neatly written in exactly ruled spaces a list, originally of ninety items, of the offerings Ra-Ka-Pou wanted brought to his tomb: he calls for ten different cuts of meat; fourteen kinds of bread and cake, among them ” roast bread,” probably toast, and cakes made of dates and figs; five kinds of grain, figs, onions, apricots(?), cucumbers(?) ; butter or cheese; four kinds of wine, water of course; green eye-paint; cloth, incense, perfume, sacred oils of various kinds, oil of cedar, Libyan oil; “the chief things of the altar,” “all sweet things” and “all growing things.”

Below the heaped up offerings are two registers which show the servants of Ra-Ka-Pou preparing the offerings and carrying them towards the false door. The first man carries something (effaced) in each hand; the second, a foreleg of beef ; the third, a tray of tall loaves and a bunch of lotus on his right arm, a duck in his left hand; the fourth, two trays of bread and cakes, topped by ears of corn(?) ; the fifth, a huge crescent-shaped bowl or basket filled with pointed jars and loaves or cakes; the sixth, a tray of tall loaves, lotus flowers, and a duck; the seventh, two trays of loaves, corn and jars, while over his left arm is hung a bunch of lotus and from his right a forequarter of beef. The eighth carries a live goose, his right hand grasping its beak to prevent its pecking him; he is followed by a man with another crescent-shaped basket, a second carrying a tray of cakes and a bird, a third carrying a tray of joints of meat, papyrus and lotus, etc. The procession turns the corner and continues on the narrow walls beside the entrance door. On the lowest register of the right wall we see the butchers cutting up the trussed oxen. The ” butcher” and his ” assistant” stand one at each end of the carcass; each has his name written above him. The assistant always merely grasps the foreleg, while the butcher, who has his whetstone tied by a long string to his kilt and stuck in the back of his belt, wields the knife. Attendants stand beside them, loading joints on their shoulders, or walk towards the false door bearing the joints of meat. An inscription above their heads and one running down the edge of the false door behind the colossal figure of Ra-Ka-Pou, announce that this is “the occasion of the bringing of offerings,” to Ra-Ka-Pou.

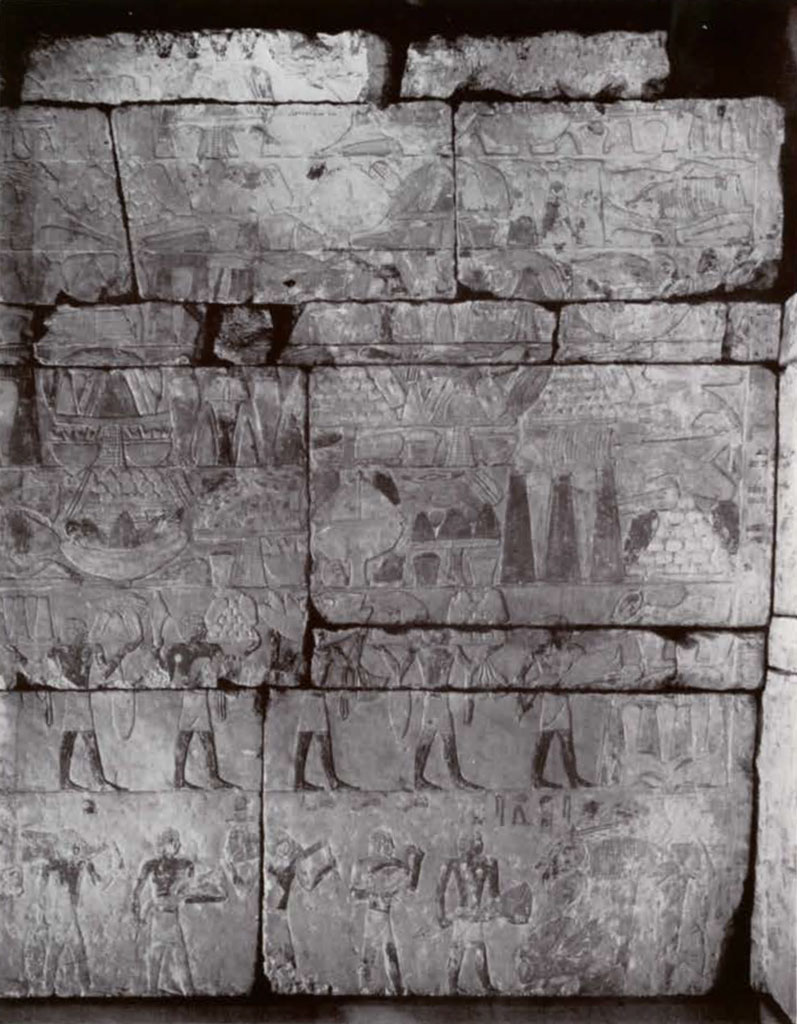

On the small back wall is a similar scene, badly defaced, of Ra-Ka-Pou seated at a table, a shorter list of offerings before him, more offerings piled below the table, and more servants carrying similar offerings towards the false door. On the lower part of this wall, and the adjoining part of the left wall the color in several shades of red, brown and yellow, bright green, blue and black, is astonishingly well preserved; and in the corners where it framed each wall may be seen the typical Egyptian border of successive red, blue, green and yellow blocks, that appears a thousand years later in the Palace of Merenptah.

The left wall is the most varied and interesting of the tomb. Almost the entire upper quarter towards the back is occupied by stores of offerings: much of it as clearly and brightly painted as if it had been done five, not five thousand, years ago. Here and there fine lines painted on offering table or vessel enable us to conclude that that shape was made of basketwork, not stone or pottery. Some of the oval-shaped objects commonly called loaves are painted so conventionally in diamonds and dots as to suggest that they might have represented boxes of meats such as were found in Tut-Ankh-Amen’s tomb.

The lowest two registers balance those on the opposite side of the tomb, with a scene of the butchers at work and porters carrying off the dismembered joints, and above, a long line of porters laden with every sort of offering to add to the store accumulating in the corner.

Museum Object Number: E15729

Image Number: 142945, 31205, 31206

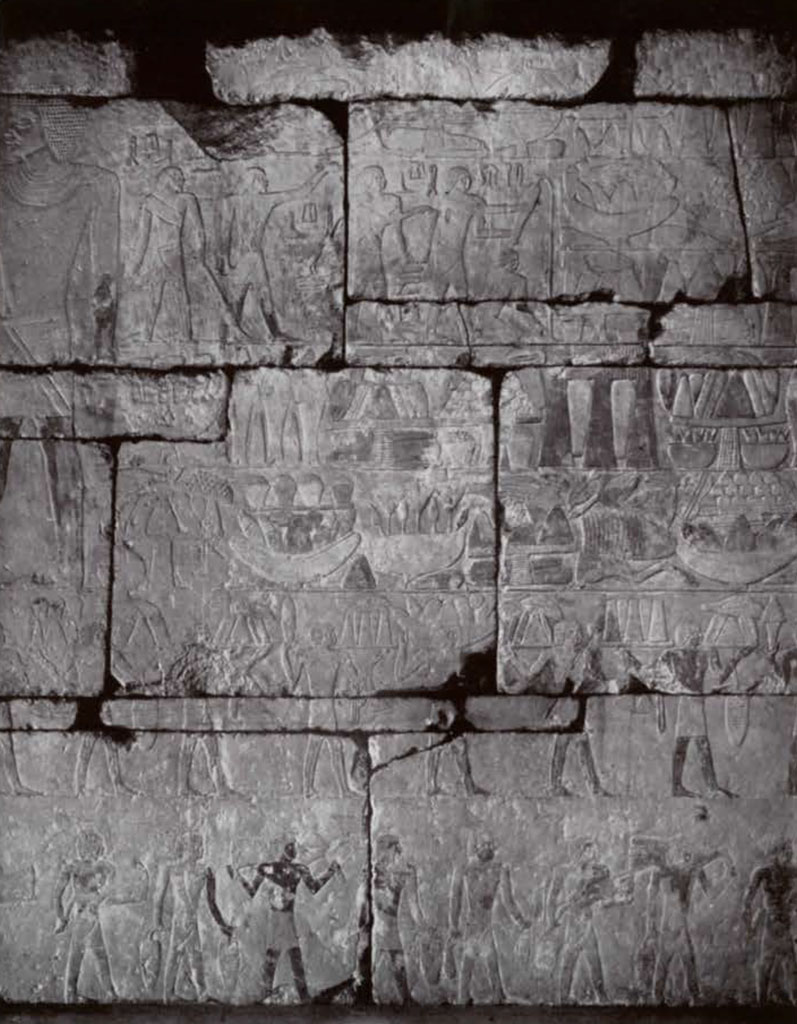

In the center of the wall is a huge figure of Ra-Ka-Pou, standing, staff in hand, and just behind him, on a level with his shoulder, is one of the most interesting scenes in the tomb: a scene of purification. A man kneels on the ground, while behind him a priest, entitled “Sehetch inspector of servants of the Ka” (of Ra-Ka-Pou), pours water on the ground before him. Behind the sehetch stands a heb priest, carrying a block or writing tablet in his hands; behind him there is another heb priest, raising his left hand and holding a short stick in his right; while last of all stands a heb priest, with his back to the others but his head turned towards them, resting the implement in his left hand on the ground. The heb priests wear long wigs, unlike the others of the tomb, and wide bands passing over the right shoulder and under the left arm.

The large standing figure of Ra-Ka-Pou in the center of this wall is the most carefully modelled of all the representations of him in the tomb. If this is a portrait we are forced to conclude that he was neither young nor handsome. In front of him, only as high as his knee, is a miniature replica of Ra-Ka-Pou, which, from the Sa-sign above his head, I take to be a representation of his son. The inscription informs us that Ra-Ka-Pou is inspecting here the offerings brought before him.

Facing him come the most charming bits of sculpture in the tomb: on the top register a woman is carrying a basket on her head, and leading a wee kid, followed by two men, each leading a young oryx by the horns with his left hand, while his right strokes the beautiful creature’s muzzle. On the next register come seven women, carrying baskets of offerings on their heads, one leading a lamb, one a kid, and one a calf, by cords tied to the little animals’ left forelegs. In front of each is written the name of Ra-Ka-Pou’s estate from which she comes. It is interesting to note that all the women carry their baskets on their heads, while the men carry them always on their shoulders. Following the women comes a man leading two magnificent oxen, while two more, their halters hanging free, walk peacefully alongside. In the register below are three flocks of birds: “two thousand Numidian cranes,” “two thousand two hundred geese,” and “two thousand therp geese.” This whole register has a charming grace, and is an excellent example of rhythm, a quality too often denied to Egyptian art, even by kindly critics. The modelling of all the animals is graceful, sympathetic, and accurate.

The general effect of the tomb is far more gay than sad, and if we imagine the very brilliant coloring that must originally have covered the walls, we perceive a scene rich and imposing in its effect. The hieroglyphs are bold and carefully cut; the sculptures, in spite of the inevitable monotony of the procession and the awkward conventions of representing the human figure, have a freedom and vigor seldom equalled at any other period of Egyptian art.

Mariette calls attention to the fact that in the mastabas of the Old Empire there are nowhere representations of divinities or divine stories: “Everywhere that which is spread before the eyes does not leave this world. One sees the deceased at home, surrounded by his family, enjoying a peaceful and happy life as the Egyptians of that time conceived it. Those strange gods who greet the dead at his entrance into the other world are also absent. . . . It is the entire household of the deceased that we see pass before him and place funeral gifts at his feet. . . . In one sense the inner room of the mastaba belongs not to the dead, but to his survivors; the wife, the children, the servants rejoin each other there. At certain religious festivals of Modern Egypt (even every Friday) relatives are seen going toward the cemeteries, carrying the bread, cakes, onions, dates that they will place at the head of a tomb. The Old Empire already had this custom. . . . For the relatives assembled in the inner chambers of the mastabas the dead revived. They saw him again seated at the same tables, surrounded by the same servants, sailing the water, taking part in the same hunts. Certain features of his life, scattered here and there, only served to render his memory more vivid. At the same time, according to a belief that ritual had already hallowed, they helped, in some way, his life in the other world. . . .

“The wife and son of the deceased see him thus dead and yet living; who knows whether in their ideas, the great figures in bas-relief which cover the walls and represent the deceased are not haunted by his spirit?”

Certainly one who spends a little while within the tomb in attentive observation of these varied scenes feels sure that Ra-Ka-Pou’s Ka has followed his tomb from Egypt to dwell somewhere behind its walls where they now rest in the Egyptian wing.