In the Central American collections in the Museum is a group of marble vases from the Ulua Valley in Honduras that are so unusual and of a type so distinct as to cause a good deal of curiosity among scholars and among people generally who are interested in the native arts and native customs of America. Our knowledge of the native customs of Central America and Mexico is so meagre that every item of information, added to the general fund, is sure to be received with satisfaction. For the same reason it is natural that each new discovery should become a subject of speculation and conjecture in the efforts of serious students to supply the knowledge that is lacking.

Attempts have been made to establish a relationship between these Honduras marble vases and the arts of ancient Mexico and to identify them with ancient Mexican ideas and practices. I purpose to publish in these pages for the first time complete data on this group of marble vases, so far as such data are available, so that their true relationships may be made clear or at least that errors relating thereto may hereafter be avoided.

The vases are four in number and by multiplying photographs of each I hope to present a true pictorial description of the group. In addition to these photographs I will give some drawings to help clarify the details, but all parts of the designs can be studied from the photographs alone. One of the vessels was briefly described by me in an article in the Holmes Anniversary Volume in 1916 with one photograph and seven drawings. That article contains the following passages.

Points of contact between the ancient dwellers in the Ulua valley and other centers of native American civilization left their marks in the form of numerous importations. The collection found during the excavations of 1896-97 includes objects in stone and in pottery that had their origin in parts as far distant as the Valley of Mexico on the one hand and Panama on the other.

A people who were so enterprising as to establish these various lines of communication and develop this far reaching foreign trade would not have been slow to benefit by the contact with foreign ideas which that trade brought them, and their progress would not have failed to be accelerated in consequence of their traffic.

It is not surprising therefore to find that the purely local products exhibit on the one hand a strong conservatism and on the other a degree of skill in their workmanship and an artistic merit that was not surpassed among any of the ancient civilized peoples of America.

This Ulua culture, like other ancient American cultures, is without date. That it was contemporary with the ancient Maya empire as well as with various cultivated peoples that flourished in Mexico, Costa Rica, and Panama, is proved by the products of these civilizations, unearthed at great depth below the surface in the banks of the Ulua; but until a sure method is found for determining the periods in the history of these better known peoples, such associations will not aid us in establishing the dates of corresponding periods in the Ulua valley.

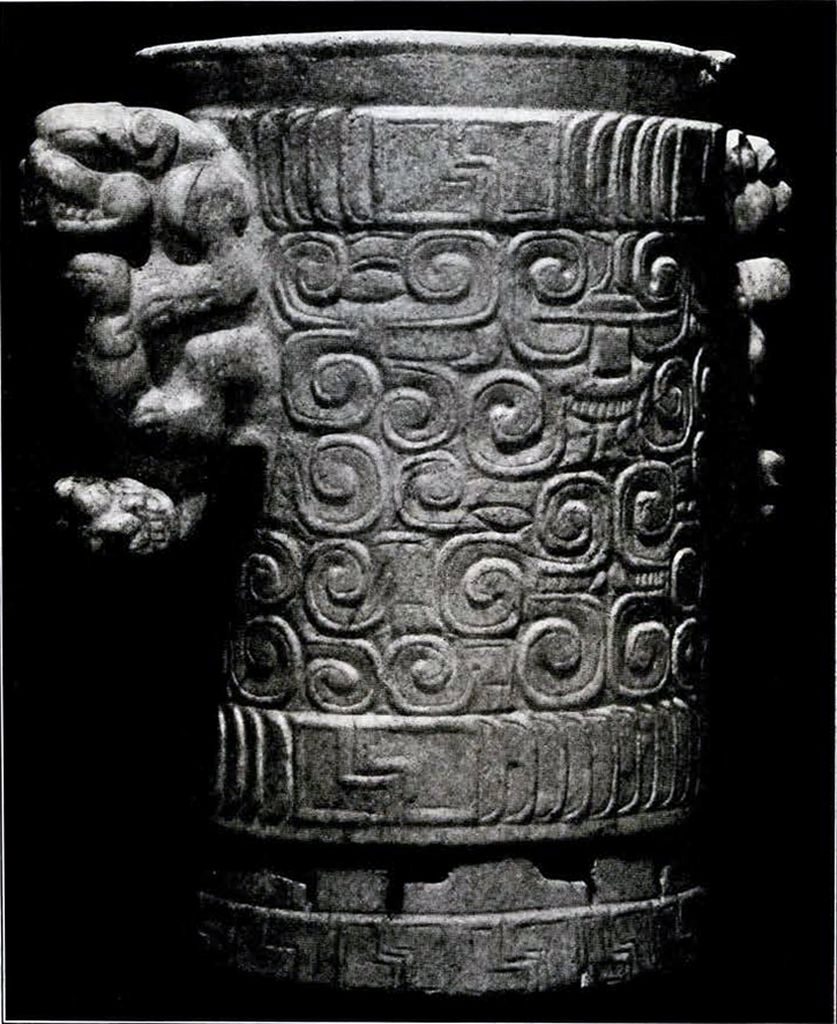

Among the objects unearthed during the excavations in the banks of the river, none possesses greater interest than a group of vessels made of a fine white marble and carved on the outside with a bold design presenting highly distinctive features.

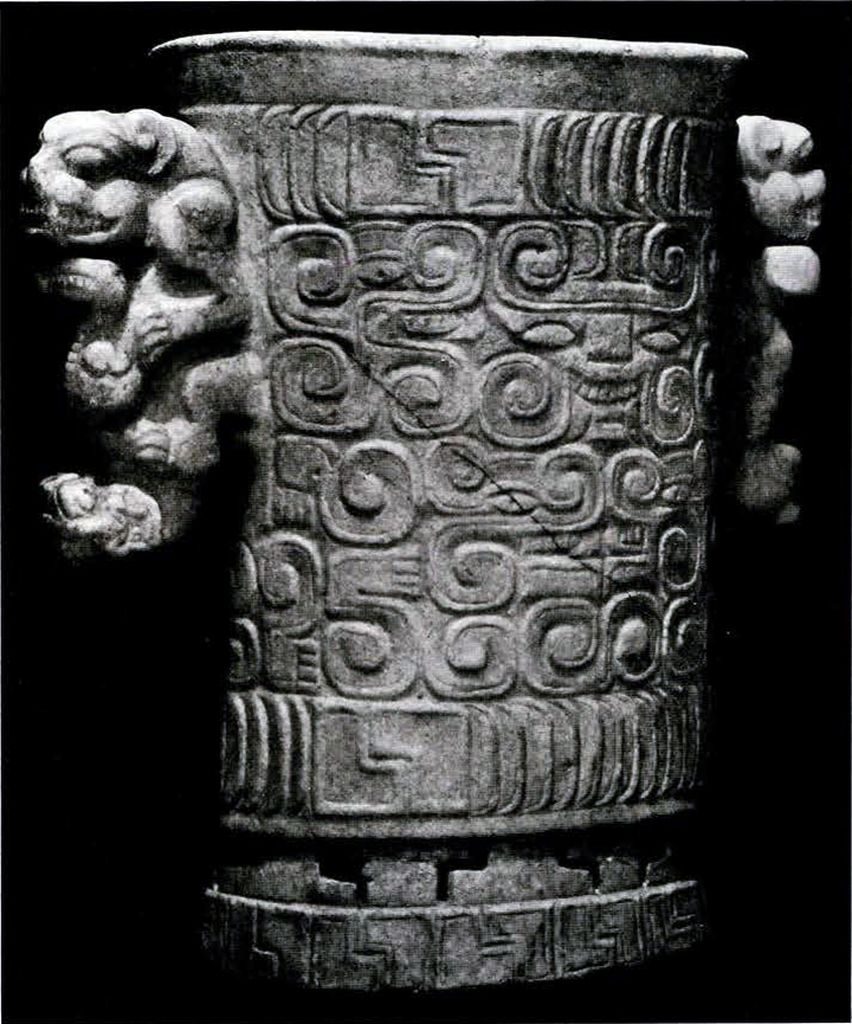

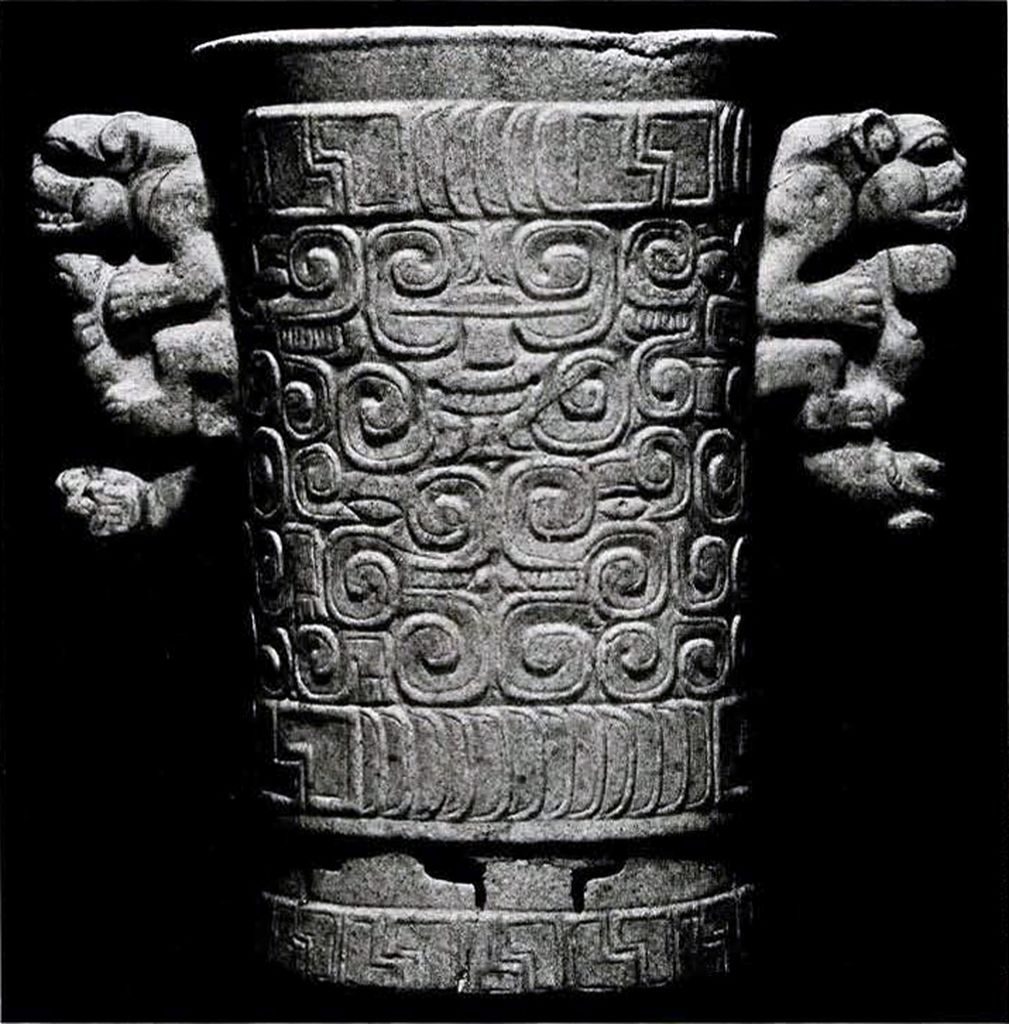

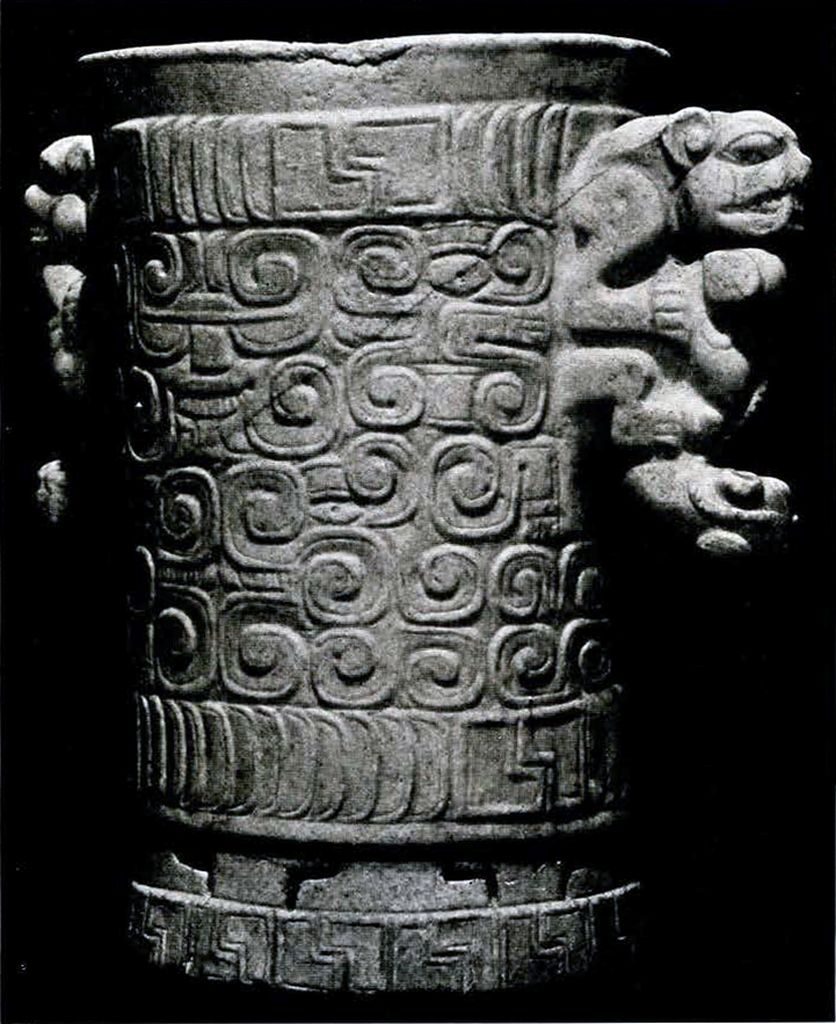

The vase measures nine and three-quarter inches high and six inches broad at the rim. On opposite sides the most striking feature is presented in the form of a pair of projecting handles, which, carved from the one piece of marble, stand out boldly from the circular contour of the vessel. The design of these handles is quite extraordinary, and its execution is no less remarkable. Each handle represents a pair of animals of different kinds, the larger animal in each case, attached dorsally to the body of the vase, forming the main feature of the handle. The head, projecting horizontally, forms the upper part of the handle. The smaller animal is held in the claws of the larger. The position is so reversed that the head forms the lower termination of the handle. The ventral surfaces of the two animals, being brought into close contact, are not sharply defined in the carving of details. The dorsal part of the smaller animal however is carved in detail, with a serrated line which extends from the head to the end of the tail. The head of this smaller animal is turned sideways so as to face to the left in each case.

The animals represented in these two remarkable groups present distinguishing marks, but it would be idle to attempt to identify the species. There is a presumption in favor of supposing the larger one to be either the jaguar or the puma, because these are the two most conspicuous animals of Central America. There is some suspicion also that the smaller is the iguana.

The cylindrical surface of the vase is divided into four zones. The uppermost zone consists of a plain rim and a sculptured band. Next comes the principal band occupying the body of the vase and entirely covered with ornament of elaborate and curious composition. Below this is another band of ornament corresponding to the one at the top, followed by a narrow plain band. The fourth zone occupies the base of the vessel, which is an inch and a half high. This surface is again divided into two bands, the upper of which is perforated at intervals, while the lower is worked out into a simple decorative border. The broad central zone corresponding to the main field of decoration claims especial attention.

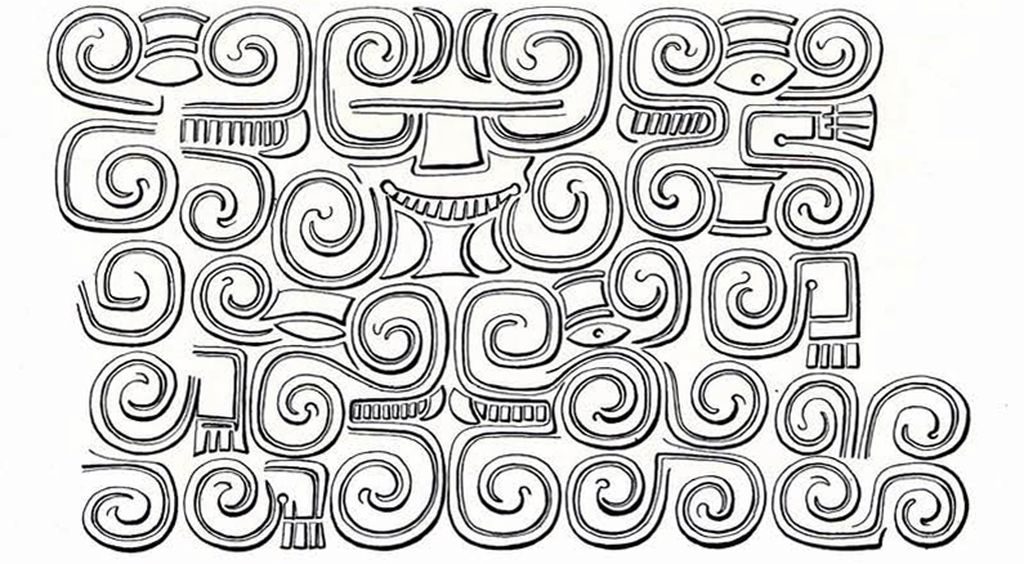

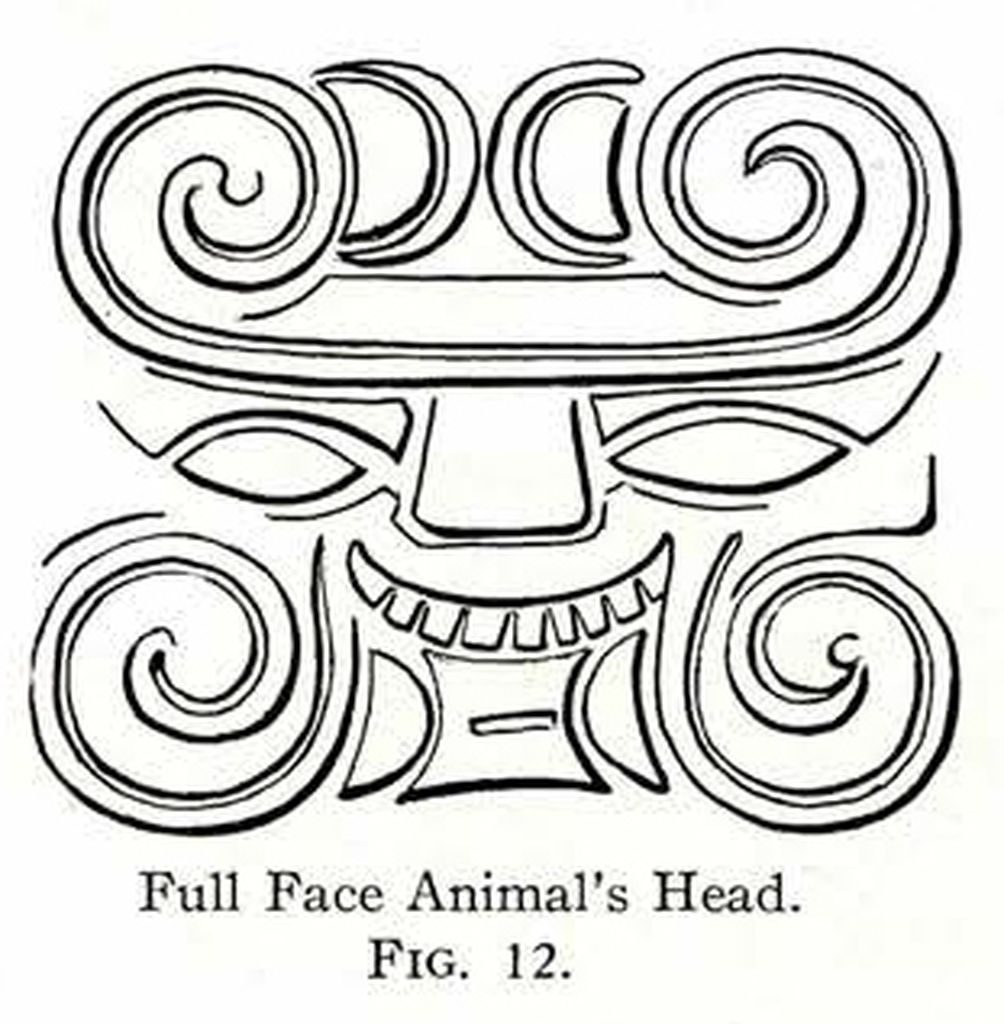

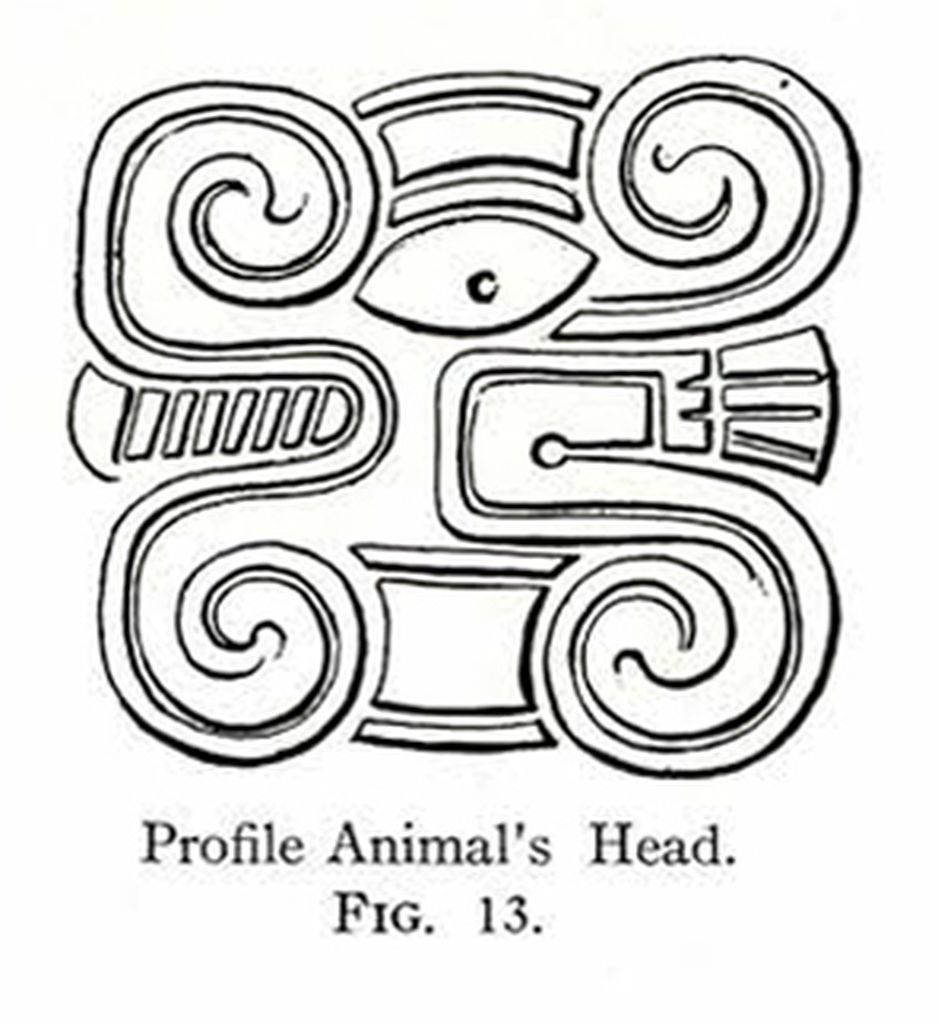

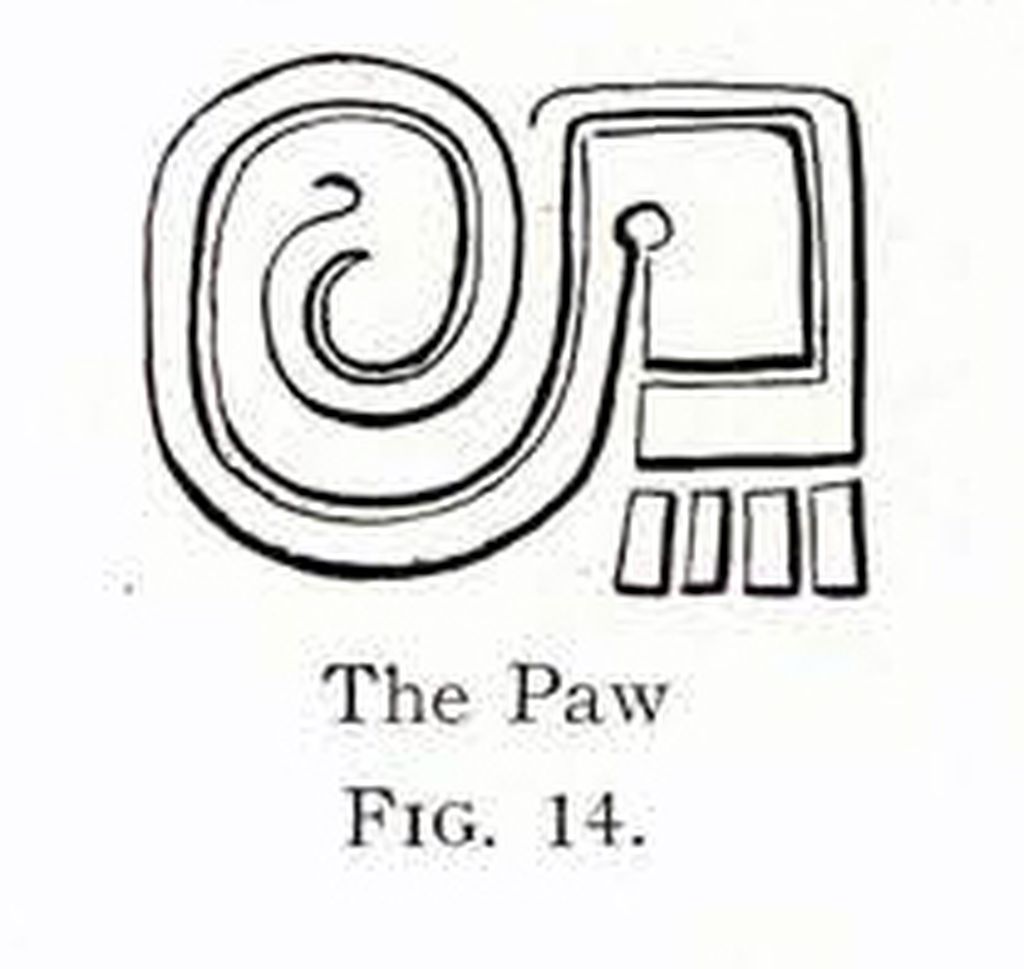

In order to explain the elements or units that enter into the composition of this ornament it is necessary to have recourse to drawings and to divide the contour into two semicylindrical surfaces separated by the handles. Fig. 12, which may be called the principal unit in the design, is repeated with striking alterations on the other side. The next unit of design is shown in Fig. 13 ; it occurs eight times, yet in no case is it repeated in the same form. The other units of design are those shown in Figs. 14, 15, and 16, each of which again passes through its conjugation on either side of the vessel in making up the composition of the ornament. It is obvious that the units shown in Figs. 14, 15, and 16 are abstractions borrowed from one of the animal forms. The entire zone of ornament is developed in Fig. 3, 10 and 11.

Museum Object Number: NA5526

Image Number: 19507

Museum Object Number: NA5526

Image Number: 19509

The distribution of the various units of design is such as to produce a well balanced effect, and a first glance gives the impression that this balance is produced by repeating the units symmetrically in such manner that each unit is balanced by its counterpart placed in contrary motion opposite. To assume this to be the case, however, would be a great mistake, as anyone will find who attempts to copy the design. The variety of expressions with which the few elements are introduced in their assigned positions in order to give balance without repetition, and with the entire absence of mechanical effect, is admirable. A similar refinement of feeling distinguishes the entire vase. While in itself perfectly symmetrical to the eye, its lines are not mechanical, and they are not laid down by any instrument of precision. The ornament in all its parts betrays the same characteristic freedom. Even the bands above and below the main zone, although composed of the same elements, occur in different numerical combinations and in contrary motion.

It would be as useless to speculate concerning the symbolism of all this ornament as it would be to guess at the service for which the vessel was designed. We are at liberty to assume that so elaborate

and refined an object had ceremonial function and that its a symbolism corresponds to ideas associated with its use, but its interpretation is quite beyond our reach.

What I am concerned with here, however, is not so much the interpretation of this object with respect to its symbolism as to call attention to its qualities as a work of art. These are of very high order and of such character that they afford striking demonstration of certain relations and bring into view a number of interesting facts. The artist that executed this work was a master of design; it would indeed be difficult to match it anywhere. His art, moreover, is the expression of a liberal culture that must have had a wide application. It had those qualities of conscious power that everywhere marks a definite stage in the progress of human endeavor in the field of art. It corresponds to the period of instinctive feeling. It is a phase of art that belongs to that older inheritance of rugged strength and assurance of his hand is spontaneous. It is a phase that always precedes, by a very long way, that period of labored affectation and painful groping that is our more recent inheritance in the field of art. It is so remote from our own artistic experience that we wonder at its appeal.

Museum Object Number: NA5526

Museum Object Number: NA5526

Image Number: 19513

This ancient vase from Honduras carries with it qualities that are common to all treasures of antiquity wherever they may be found. It adds the weight of its testimony to the abounding evidence that culture in ancient America had made great and diversified advances, and that among many prehistoric peoples of the western continents a very fine artistic sense prevailed. It helps us to form a true estimate of the place which the prehistoric Americans occupied among the civilized peoples of antiquity.

In the magazine Art and Archeology, Vol. XI, Nos. 1-2 (Washington, 1921), Mrs. Zelia Nuttall offers some comments on this article of mine which was afterwards reprinted with some verbal omissions and with the omission also of five of the explanatory drawings in the magazine above mentioned. (Vol. IX, No. 3, Washington, 1920.)

In her comments Mrs. Nuttall commits a number of mistakes that had better be corrected. For the most part the photographs will be found sufficient for the purpose. For the rest it will only be necessary to present a few statements of fact concerning the material and design that enter into the composition of these Honduras vases in the University Museum.

Mrs. Nuttall observes that I made no allusion “to the fact which is so vital and interesting” that the principal units of design which I described “are conventionalized serpents’ heads.”

It is true that I made no such allusion for I was under the impression that these units of design are something quite different. So clear was this impression in my mind that I contented myself with giving accurate drawings of each, together with a photograph of the vase and the statement that the units of design are abstractions borrowed from one of the animal forms represented on the handles. My thought was that anyone who would be likely to read my article would need no further help in identifying the units of design on the cylindrical surface with animal forms expressed in the handles.

Mrs. Nuttall proceeds with this statement : “These serpents’ heads are clearly discernable in the photographic reproduction of the vase which illustrates Dr. Gordon’s article, but curiously enough, are barely recognizable in the carefully executed outline drawings.” She then offers as a substitute for some of the drawings that accompanied my article, certain other drawings to which she refers as follows. “To make this clear, the Mexican artist, Sr. Jose Leon has made drawings from the published photographs in which the forms of the conventionalized serpents’ heads and the peculiar technique of the native sculptor . . are skilfully rendered.”

Museum Object Number: NA5526

Image Number: 19511

Museum Object Number: NA5526

Image Number: 19512

Only one photograph has been published heretofore and this, the one that accompanied my article, was the only one to which Sr. Leon could have had access. It shows one aspect of a cylindrical surface, which does not afford scope for an accurate drawing of the foreshortened parts. The drawings published by me were made from the original object by Miss M. Louise Baker under my direct supervision and criticism. They are accurate and strictly literal. Moreover, they reproduce faithfully the character of the carving which is vigorous, free and spontaneous. On the other hand the illustrations that Mrs. Nuttall reproduces are inaccurate in drawing and are deficient in the freedom and strength that characterize the original workmanship.

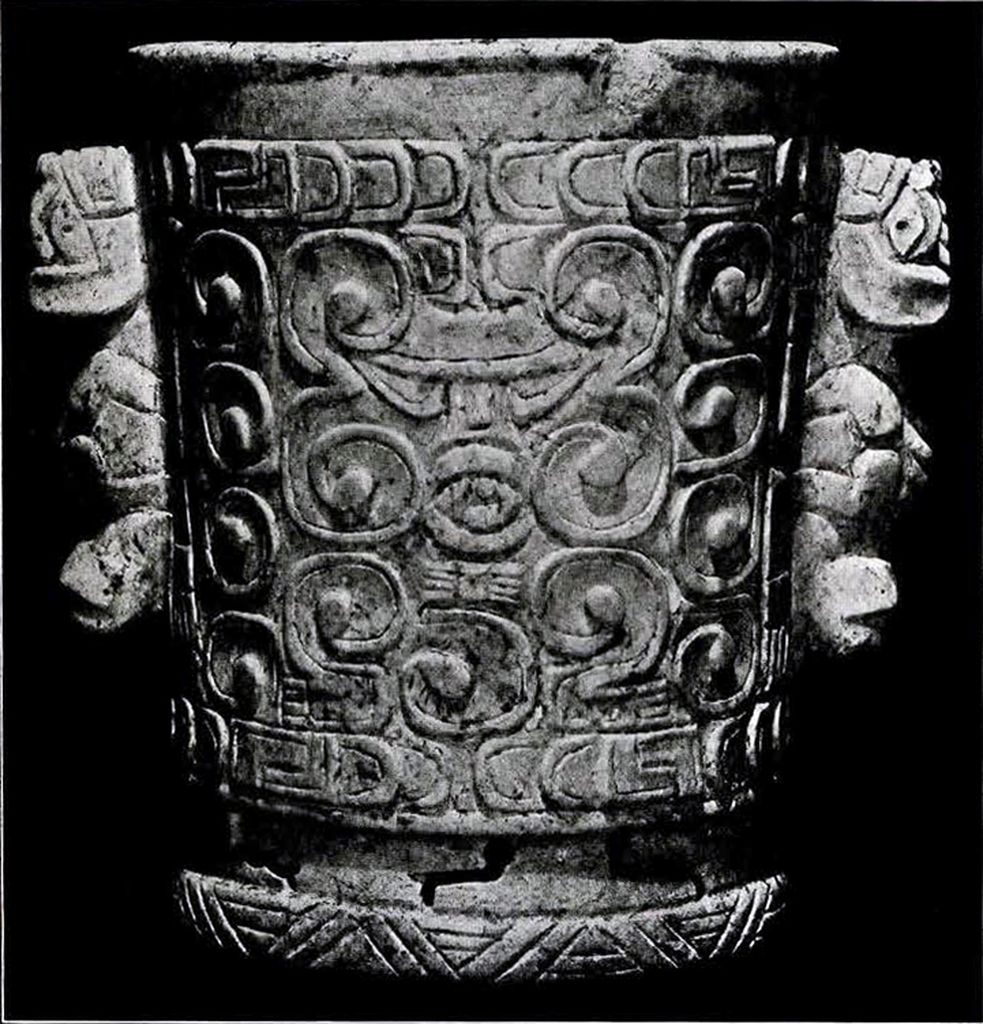

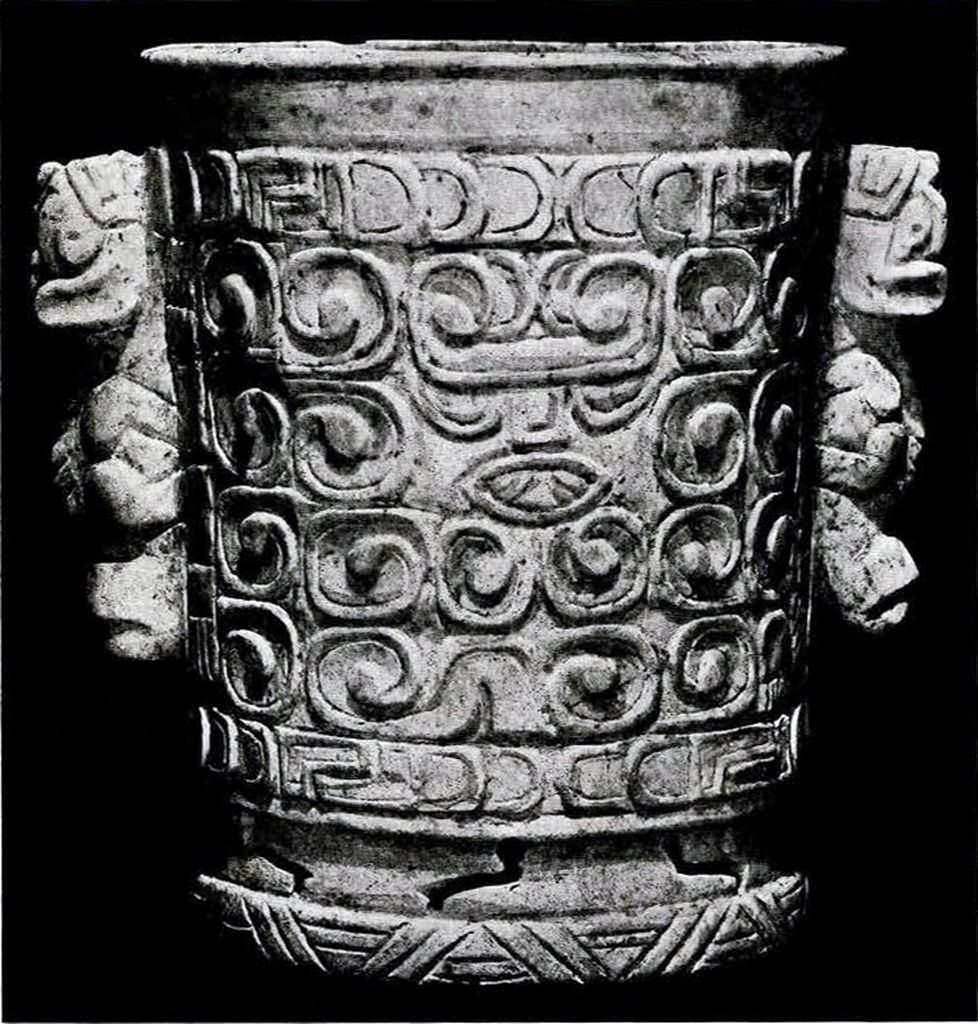

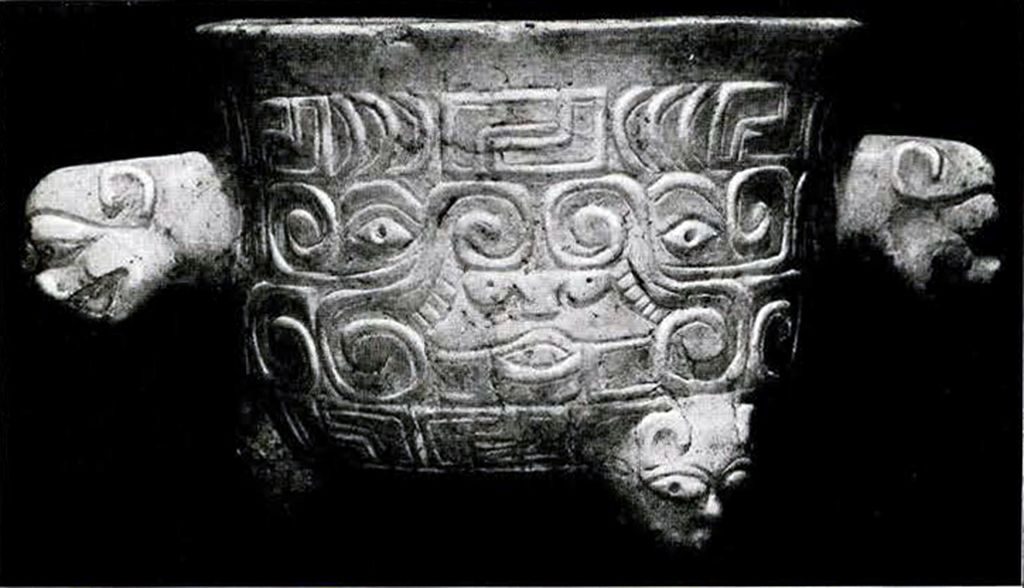

The fact is that there are no serpent heads at all on the Honduras vase. The devices that Mrs. Nuttall calls serpents’ heads are different ways of showing the heads of the animals that are represented with more realism in the handles of the vessel. These animals are quadrupeds and the whole design on the body of the vase is made up of parts of these animals as follows: the front face, the profile, the paw, the ear and the jaw.

Having started with a wrong identificaticn Mrs. Nuttall was quite naturally led into an erroneous interpretation, for being subject to this correction, the meaning which she ascribes to the design loses its only support.

In her next argument Mrs. Nuttall makes the statement that no true marble has been found in Mexico or Central America. It is evident that Mrs. Nuttall has been generally misled on the subject of marble, for she claims that the substance found in the State of Oaxaca and locally called técali is not marble but onyx and that this local product is the material from which “numerous ancient vases and vessels unearthed in different parts of Mexico and Central America . . . are made . . .”

Therefore, the argument runs, the vase which I call marble is in reality made of onyx, and since that material comes from Oaxaca it follows that the vase itself cannot be a product of Ulua culture, and must have been imported from Mexico.

Here are three fallacies combined to support each other. First, that the material found in Oaxaca and locally called técali is onyx; second, that there is no marble in Honduras; and third, that the object of which I wrote is made of onyx.

As these errors of Mrs. Nuttall are based on popular notions and a habitual looseness in the use of language by writers generally, and on a confusion of terms, they had better be set right for the sake of general accuracy. The substance called tecali found in Oaxaca, and used by the ancient Mexicans in the practice of their arts and industries is marble and not onyx. It is popularly called Mexican onyx and also onyx marble on account of its banded appearance that gives it a superficial resemblance to onyx. It is a carbonate of lime with a compact crystalline structure and a true marble. Onyx is a hard silicious mineral quite distinct from marble and unrelated thereto. Geologists tell us that the Mexican marble found at Técali in Oaxaca was deposited in the form of stalagmite and belongs in the same class of marbles as the so called onyx marble of Algeria, the stone that was largely used in the building of ancient Rome.

Museum Object Number: NA5527

Image Number: 19514

Museum Object Number: NA5527

Image Number: 19515

Mrs. Nuttall tells us that “as yet no true marble has been found in Mexico or Central America.” This is a comprehensive mistake. True marble has been known within these regions for a long time. Besides the deposits in Mexico there is a well known deposit of marble in Honduras near Omoa, adjacent to the Ulua River. This deposit was described by E. G. Squier in his book, The States of Central America, published in 1858, in the following words.

“The hills and mountains back of Omoa have exhaustless quarries of a fine compact white marble remarkably free from faults and stains and well adapted for statuary and ornamental use.” (Page 189.)

The same words are repeated in Squier’s book on Honduras published in 1870. (Page 125.) The deposit of marble at Omoa is not of the banded variety found in Oaxaca and is easily distinguished therefrom. The material from which the Ulua marble vases are made is identical with the marble of Omoa.

These considerations would seem to dispose of Mrs. Nuttall’s contention that “Until other ancient quarries are found and it is proven that a marble was obtainable in the region of the Ulua River, Honduras, one may be permitted to question Dr. Gordon’s view that the vase in question is of marble and a product of Ulua culture.”

The following facts are quite clear; namely, that Mrs. Nuttall’s identification of the figures on the body of the published vase fails to be supported by an appeal to the figures themselves; that her drawings of these figures are incorrect and indicate an entire want of comprehension; that her interpretation of these figures is without foundation; that her proposals about the material of the vase are made regardless of the facts; that her suggestion as to the origin of the vessel is inadmissible in view of these facts, and finally, since her description of the use of the vessel is based on a combination of the foregoing errors, it is clear that her ideas on that subject must also be rejected. In short, Mrs. Nuttall’s article has confirmed the opinion that I formerly expressed in the following words.

“It would be useless to speculate concerning the symbolism of all this ornament as it would be to guess at the service for which the vessel was designed. We are at liberty to assume that so elaborate and refined an object had a ceremonial function and that its symbolism corresponds to ideas associated with its use, but its interpretation is quite beyond our reach.”

Each of the five vases presents the same general features as the one described. That one alone presents two animal figures combined in the handles, but the others show on the handles or handle one or the other of these animals, sometimes one and sometimes the other. In each instance certain features of that animal, full face, profile of head, paw, ear or jaw or a combination of all these features are graphically represented on the cylindrical surface.

Mrs. Nuttall’s errors are indeed quite natural for they are based in part on inadequate data, in part on misconceptions that are quite common, and for the rest on methods that find much favour. It is due to her and to all students of Mexican and Central American antiquities that such data as may be preserved in this and other museums should be made available for their studies.

G. B. G.

Museum Object Number: NA5527

Image Number: 19516

Museum Object Number: NA5527

Image Number: 19517

Museum Object Number: NA5528

Image Number: 19519

Museum Object Number: NA5528

Image Number: 19518

Museum Object Number: NA5528

Image Number: 19520

Museum Object Number: NA5529

Image Number: 19521

Museum Object Number: NA5529

Image Number: 19522