IN Greek thought as in Christian, it was held an act of virtue to bury the dead, or rather, since the soul wandered helpless and hopeless until the body was laid to rest, it was considered an act of impiety not to give it burial. Only those who merited the extreme penalty were denied the solace of burial rites. What these rites were is known from Lucian’s De Luau and from the many vases on which are depicted the prothesis or laying out of the dead and the funeral procession itself. A flute-player and the mourners walked behind the bier, and after the body had been interred or cremated, for both practices were followed in classical Greece, the family returned to the house of a relative to partake of the funeral feast, of which the dead was regarded as the host and by means of which the living established communion with the dead.

Image Number: 3663

The place of interment was without the city wall and generally along a highroad in order that, in a land of dust and mud, the graves might be accessible for the offering of gifts and also doubtless that passers-by might see and admire the funeral monuments erected above them. Along the Sacred Way from Athens to Eleusis, the tombs of the dead interspersed with shrines and sacred precincts extended for many miles. It might be thought that the traveller approaching Athens by this highway would be oppressed by the sight of so many tombs. But the Greeks, despite their belief in a dim and shadowy hereafter, were less troubled by the reminders of death than the Christian who professes a livelier hope. Indeed, the monuments along the Sacred Way were one of the sights of Greece. The antiquary Polemo devoted an entire book to their description and Pausanias, who travelled that road in the second century after Christ, made notes, which fortunately are preserved to us, of the most important monuments which he saw. Generals and ambassadors, the painter Heliodoros, the tragic actor Theodoros, were among those whose tombs Pausanias admired. It was a great scandal that, near the pass of Daphne where travellers from Eleusis first catch sight of the Acropolis, the Macedonian Harpalos, chargé d’affaires for Alexander, erected a tomb in honour of the courtesan Pythionike at a cost of $100,000. Such extravagance in setting up funeral monuments was more than once the object of special legislation at Athens. Shortly after Solon’s time a law was enacted forbidding the erection of a tomb more elaborate than could be built in three days by ten men. This law seems to have fallen into disuse, for Demetrios of Phaleron had a law passed forbidding other monuments than a short column, a flat slab, or a vase. As a result of these measures most of the grave monuments found in our museums today date from a period which falls between the Persian wars and 300 B.C.

Museum Object Number: MS5675

Image Number: 3322

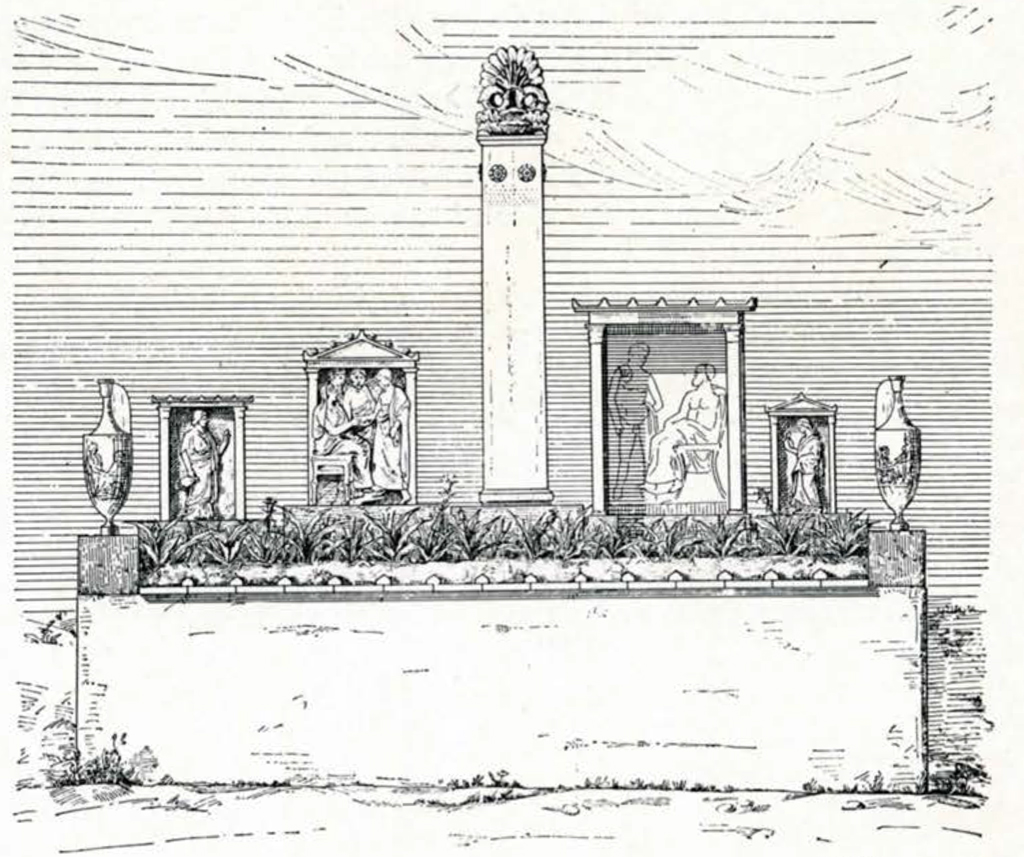

Just outside the Sacred Gate at Athens, which, like the Gate of Sorrow in Burma, was devoted to the use of funeral processions, was the potter’s field or Kerameikos, and here the graves were so numerous as to constitute a veritable cemetery. To the beauty of the monuments which were set up here Cicero paid tribute when he spoke of “amplitudines sepulcrorum quas nunc in Ceramico videmus.” The pride and pomp of the Sacred Way has vanished, but the grave monuments of the Kerameikos, preserved through the centuries under an unusually deep deposit of earth, have been brought to light in our time and may well be considered the most beautiful monuments ever erected to the dead. The excavation of the Kerameikos was begun by the German Archaeological Institute before the war and has lately been resumed by German scholars with funds given by a citizen of Reading, Pennsylvania. Thanks to these researches it is now possible to form a picture of how the sculptured monuments so prized by our museums today were placed. They were set not on the level of the roads but on high podiums of masonry, a conjectural restoration of one of which is shown on page 248 together with the monuments which surmount it. It will be seen that more than one type of stone was used within a family plot; for some members of a family a tall shaft was erected crowned by an anthemion, for others a naiskos or stele deeply set with a gabled roof, for others a flatter rectangular stone. At the corners of a plot and serving as akroteria for the whole construction are set marble lekythoi adorned with the same types of sculptured ornament as are found on the stelai.

Museum Object Number: MS5709

Image Numbers: 171606, 46895, 46896

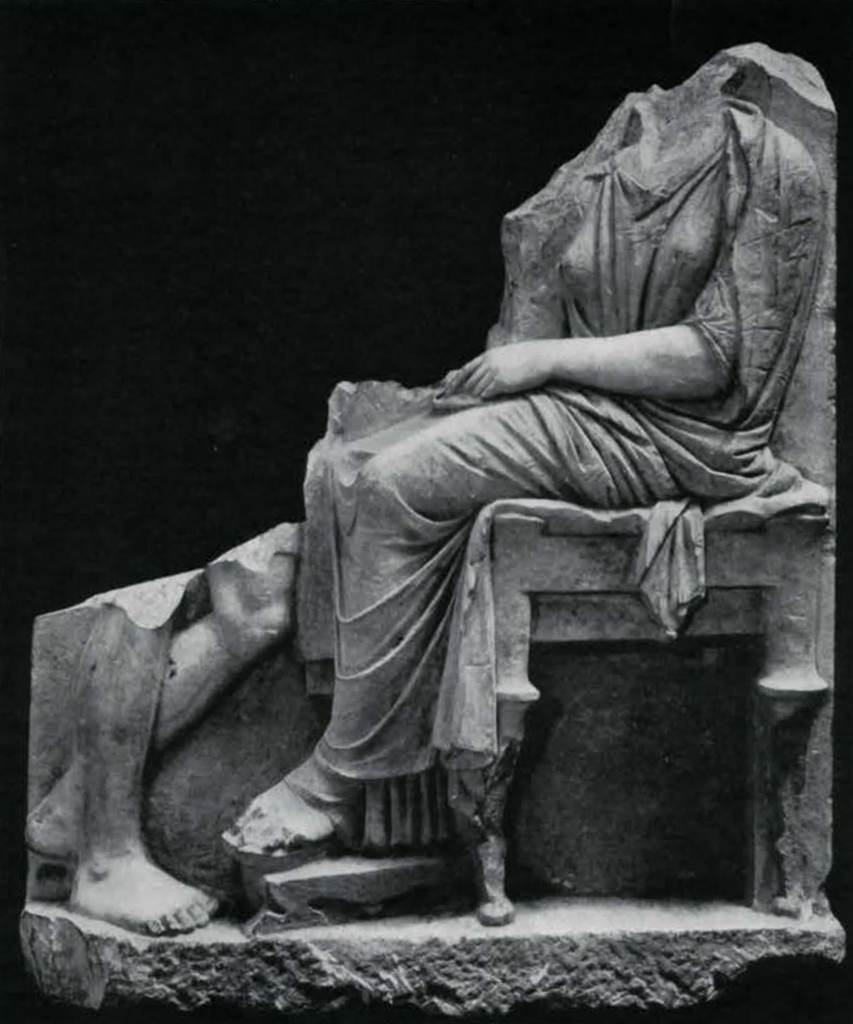

The UNIVERSITY MUSEUM has recently acquired three Greek grave monuments which, although their provenance is unstated, were probably set up along some Attic highway, since the material in each case is Pentelic marble. The first of these (page 250) is a fragmentary stele on which is preserved the figure of a seated woman and the bare legs of a smaller figure facing her. Only a portion of the drapery of this second figure is preserved, above the knee next the woman. It seems to indicate the short cloak or chlamys worn by men and boys when travelling and suggests that the scene represented a young boy taking leave of his mother. The costume of the woman is of some interest. Her sheer undergarment is pinned with brooches along the arms to form sleeves. In the heavier outer garment occur at intervals pairs of short lines which represent the woven pattern of the material and were originally picked out in a colour contrasting with that of the robe itself. The longer lines which appear on the shoulder and breasts also represent woven stripes once coloured.

Museum Object Number: MS5709

Image Number: 3155, 3156

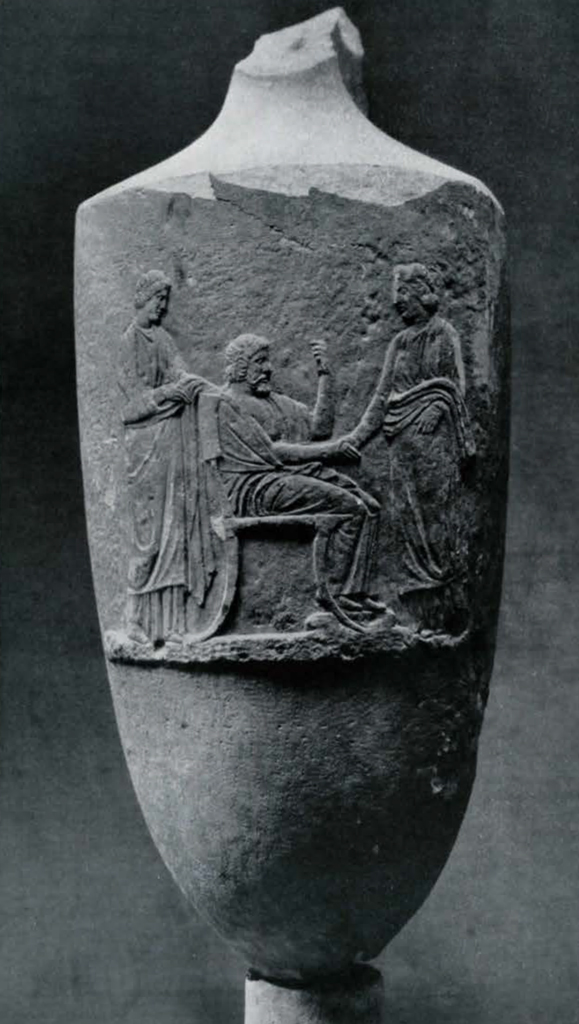

The second monument (page 252) is a marble lekythos of the type which appears at the corners of the restored plot on page 248 and which is to be regarded as a translation into stone of the clay vases offered at tombs. Above and below the zone of the sculptured figures may be detected bands of carefully tooled stone prepared for the application of coloured pattern, perhaps the maeander. The German excavators found in the Kerameikos a marble lekythos with a painted maeander below the sculptured field and an elaborate palmette design on the neck, the colours, blue, red, and gold, still beautifully preserved. On pages 253 to 255 are shown in larger dimensions the three sculptured figures which stand on a slight ledge of marble left in higher relief. A family group is represented; in the centre the father, behind his chair the mother, and grasping her father’s hand the young daughter in whose honour we may believe the monument to have been erected. Inscriptions show that parents set up monuments for their children more often than children to their parents. Those who lived to a ripe old age were not so often honoured with a monument as young warriors who died in battle or young wives who died in childbirth. Although the execution of these figures is somewhat summary, they are conceived according to the best Greek tradition. The simple coiffure and the dignified mien of the mother continue the noble traditions of sculpture of the fifth century. There is no trace of the staff on which the hand of the central figure rests, and since there is no perforation between the fingers for the insertion of a staff of bronze, it follows that it was once rendered in colour. And if the staff, so also the garments, the hair, the chair. The inscriptions also which are carved above the heads of the figures were doubtless coloured. The mother’s name is Kleostrate, the daughter’s Melitta. The letters over the father’s head do not spell any name nor are they a possible combination. They are ΙΤΧΘΟΚΛΗΣ. Professor Roland Kent of the University of Pennsylvania, who has made a special and authoritative study of mistakes in Greek inscriptions, kindly examined these letters for me and offered this very plausible explanation. The stone-cutter was illiterate. The names given him to carve, probably written on a wax tablet, were carelessly formed and the first and second letters of this name were actually ΠV but seemed to him to be ITX. The man’s name was therefore Pythokles.

Museum Object Number: MS5709

Image Numbers: 3159, 3160

Because these figures are named, it does not follow that they are to be regarded as portraits. The Greek sculptor of this period was little interested in the rendering of individual characteristics. His repertory included a wide variety of types and these he combined in different ways to meet the needs of any given monument. The seated man, staff in hand, for example, is a type much used to represent a dignified and respected man of middle age or more. It is closely related to the type used for Asklepios, the god of healing.

Museum Object Number: MS5709

Image Number: 3162

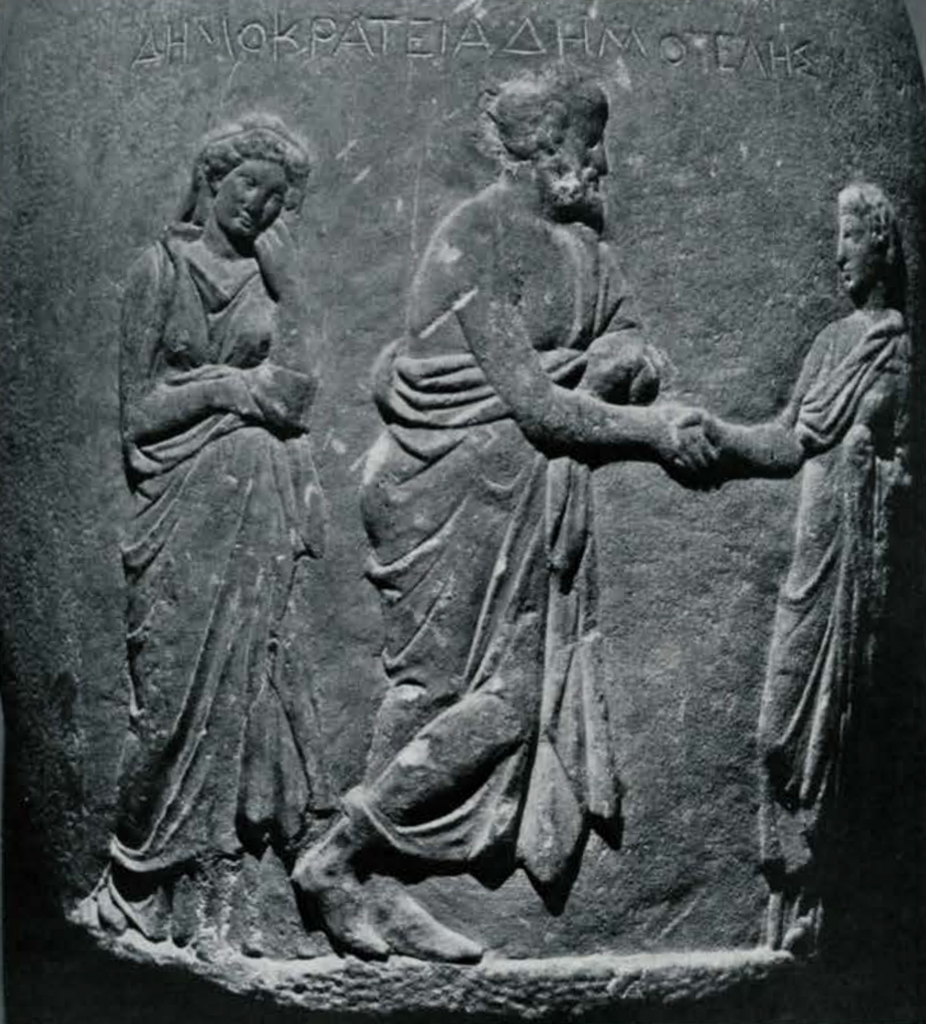

The third grave monument is a marble vase of different shape, page 256. The shoulder is rounded in a beautiful curve and still shows remains of bronze rivets by means of which the handles were attached. The remnant of a pour-handle may be seen at the neck. Clay vases of this shape were used to carry water from the spring Kallirrhoe for the bridal bath, and were carried in the wedding procession. If a girl died unmarried, a marble vase of this shape was set above her tomb in token of her marriage to Pluto. That it was also used for the graves of unmarried youths is shown by a passage in Demosthenes. “What is the proof,” he asks, “that Archiades died unmarried? A marriage vase is set up on his tomb.”

In the centre of the scene stands the father Demoteles leaning on his staff which, as in the other vase, was once rendered in colour. The figure recalls the elders of the Parthenon frieze or the dignified men who in Greek vase-paintings instruct the youth in athletic contests. He grasps by the hand a slim young girl, whose name Malthake or “soft one” seems appropriate for so gentle a figure. The tragedy of the farewell is scarcely hinted in these two figures, but the mother, Demokrateia, is in the pensive attitude which typifies grief, the same type of figure which is used for the mourning women of the Constantinople sarcophagus. The curving line of her body with the hip thrown outward implies that the sculptor was familiar with the work of the Praxitelean school, so that the vase, in spite of the Phidian look of the other two figures, must be assigned, like the lekythos, to the first half of the fourth century. Neither vase is by a great master but both are far nearer the works of great masters than are the copies which were made in Roman times.