RECENTLY the MUSEUM placed on exhibition in the Tlingit Hall of the American Section a collection of objects, the greater part of which is shown as representative of the native art of the Tlingit nation. Some of the pieces are unique in character, others grotesque in form, and some of them may appear, to a stranger, as if they had served in a fantastic masquerade. But if one makes a close examination he will readily discover in most of the fine old pieces the aesthetic emotions that played the main part in their creation.

The more important part of the collection consists of objects carved of wood but there are also fine examples of weaving, embroidery, and drawing. All of these display sufficient evidence of a well-developed aesthetic sense in the mind of the native artist ; instantly it becomes evident that the taste for ornamentation, here, is not rudimentary. The intent of the maker is obvious, a distinguishing quality which marks a difference between the things shown here and things of the same nature that are produced in other parts of our land.

To know the better side of the American Indian one must learn more about his moods and emotions. Of the more important groups of aborigines, the Tlingit tribe of the southeastern coast of Alaska appears to be one of the least known. And until ethnological investigators followed the trail of the straggling natives into the most remote parts, the character of the people was not clear for the reports of the early European explorers had conveyed all but that which was most important.

Immediately after the discovery of the existence of rich furs and gold and of the salmon which abound in this northern land, a profound change took place in the life of the natives; more strange people came who eventually took command of everything. But it is to be regretted that this dominant race of people made no authentic study of the Tlingit until long after the time of the latter’s confounding by the engulfing foreign influence, when “evil water” (whiskey) and greed of trade had debauched the native ideals.

Hence, the Tlingit appeared in most publications as debased characters. But the determination to investigate did not wane, thanks to the very few qualified men who camped upon the trail of the truth of things and to the very generous persons who, from time to time, supplied funds in support of expeditions.

The lack of reliable native interpreters is now the greatest handicap to all careful scientific research. Hence the puerile form in which most of the important legends have gone into record. A Tlingit who has felt the thrill of the true quality of the old legends will experience only a feeling of indignation when reading such childish presentations of that which he has cherished. Personally, I feel, after long holding my peace, at last compelled to voice my true feelings. I realize of course that only a skilful writer of the English language can do justice to the true spirit of my people and the lack of such a qualification has always been my handicap. Being thus unprepared, I can only do the next best thing and take advantage of an opportunity which has offered itself to illustrate the true psychology of my people by the simple means of their native art.

Like all men who have a desire to accomplish something, I have experienced disappointments and discouragements but by the unfailing support and constant encouragement of the late Dr. George Byron Gordon I was put in a position to present to the public view this collection of objects, each of which has long held the unlimited reverence of my people, an esteem inspired only by those objects which are sacred to man.

It was only through a claim to some distant relationship that I was, at last, permitted to open the old chests and to take out and carry away from their sanctuaries the fine old pieces that had not seen daylight since the white man’s religion and law had supplanted those of the natives.

A stranger cannot very well appreciate the part which these old symbolic objects played in the life of the Tlingit until he has some idea of the social system of the people, so that it is very necessary to present a brief outline of this.

From the time that Tlingit history first records their settlement in Alaska, the people have existed as two great bodies. One moiety is known as Tlhigh-naedi while the other is called Shungoo-kaedi throughout the whole region, and they refer to each other as Klayade-na, “Oneside-nation”. The Tlingit word “na”, thus applied, corresponds closely to the English term “nation”, and for convenience each moiety will be here referred to as a nation, regardless of the English definition of the term. The origin of this division we must leave for future discussion and for the present content ourselves with only those things that can readily be explained.

Both nations were at first agglomerations of independent groups which are termed clans. A clan is a subdivision comprising a number of household groups and known by a name which in turn is derived from the subdivision’s original geographic location.

With the development of culture, clans became classified according to paternal descent, a classification in which different ranks were assigned. Hence the creation of objects called totems and the adoption of some living thing by which one might be identified became necessary. The immediate presence of the raven, whale, beaver, eagle, bear, wolf, and other denizens of the forest and sea of the region, and the Tlingit knowledge of their peculiarities, explain the prominent part they play in the mythology and arts of the people. It is by this system of picture-writing in graphic and plastic arts that the history of my people has been preserved and transmitted through centuries.

So here they are. I hope to live to see the day when these old things will help to bring the true character of their makers into the white man’s light.

The Exhibition of the Tlingit Collection

In arranging the collection here displayed, the most important specimens are placed, as nearly as space permits, in the order of their rank. In the several cases are grouped objects illustrating the various phases of the life of the people; examples of fine carving in wood, wearing apparel, exhibitions of the arts of weaving in wool and porcupine-quill embroidery, feast dishes, war implements and trophies, paraphernalia of the shaman or medicine-man, ceremonial masks, and a complete collection Of ceremonial headdresses. In a small case lies the great hat of Shahe-he, the first woman diplomat, and in another the relics of Saetl-tin, the famous “Bride of Tongass”. Of the important pieces, the fine old headdress called “The Lord of Hawks”, which formerly held in its clutches the fate of unfortunate slaves, and the Ganook Hat, which represents the most ancient being in Tlingit mythology, are the most noteworthy. But each is important enough to be treated by itself.

In a case on the right side of the centre aisle as one enters the Tlingit Hall, stands forth like a herald who has an important message to convey the Raven Hat of the Tlhigh-naedi nation, representing culture; next in order is the Whale, an emblem of greatness, used as a crest object by the leading clan; here is also the Sea-lion, an emblem of endurance; and then the Frog, an emblem of persistence pertaining to the Kiks-adi clan.

On the left side, appearing as if it had always gazed upon the ocean, indifferent to all curious eyes, stands the Eagle, also in the form of a ceremonial hat, the emblem of the Shungoo-kaedi nation and signifying determination. Next in order is the Grizzly-bear, an emblem of power, representative of the Tae-quedi clan, and then the Wolf, the emblem of the Kaguan-ton clan and signifying courage. The old hats and helmets, indeed, portray well the symbolic ideas of their owners, for each clan, in its own geographic location, contributed its share towards the success of the nation of which it was a part. There are also other representations but we mention here only the most important pieces in order to explain the object of their presence.

Museum Object Number: NA11740

Image Number: 12634

According to the legends that refer to these old ceremonial hats, each clan well earned its possession, since to establish such in its rank had demanded much sacrifice, not only of personal comfort but even of life itself when it was necessary. Therefore it was a natural thing that as the people grew and spread wide over the region, an attitude of local patriotism overshadowed the feeling of kinship and disputes over ownership of emblematic objects became a menace to all peaceful divisions. These disputes more than once developed into serious warfare that for a time threatened the further existence of the weaker communities. At the same time men of sound reasoning and the rich, in a more intelligent manner, procured the ownership of rights and claims to those things which were deemed most honourable in the native mind.

The old Raven Hat, if it could but talk, could tell much about the thirty years’ struggle of the Ganah-taedi of Chilkat with their former kin the Tluknah-adi of Sitka. In the dispute between these two powerful clans to determine which held absolute right to the custodianship of the national emblem, the Ganah-taedi are said to have shown greater proof of being the original body. Hence, the Raven (page 367) appears among the Tluknah-adi possessions only as a symbol of alliance and is known by a characteristic name.

The popular Raven appears also among nearly every important division but usually in an unobtrusive manner corresponding to the means by which it was acquired. It is a common trait of human nature for every man to have the feeling of being a great chief in his own house, and, whatever its nature, probably his account of the origin of his possession resounded only within his own walls. But it was the general attitude of the people that counted for most in determining the soundness of a claim to ownership of an important crest object. Such were the conditions under which the Tlhigh-naedi emblem grew into popularity.

The Eagle emblem, however, was established in a more sensible and peaceful mariner in spite of the fact that at the beginning its owners appeared with an aggressive attitude, and the Eagle to the last was honoured on account of the history of its establishment. When I first listened to the legend relating how the Shungoo-kaedi obtained undisputed ownership of the Eagle I could not help but admire the astute mind of Chief Stuwuka and I feel honoured and. proud of being born of a mother who could bestow such a personal name upon her son. This incidental admission will explain my claim to some relationship with nearly every important Tlingit family.

* * * * * * * * *

One bright summer day in Chilkat I sat, squatting on the ground, the kodak with which I had just taken a photograph of the Chilkat Eagle Hat lying on my lap; I dared not make a move that might interrupt the aged Kaguan-ton who inhaled the pleasant air in a man’s day-dream of the glory of the past as he recited, with unconcealed pride, the part that his ancestors played in establishing the national emblem, occasionally pointing to the old ceremonial hat where it lay on a log as he went on to tell the story of the Eagle emblem.

In this study of Tlingit mythology, it is interesting to note the narrator’s preliminary remarks and his personal opinion on different subjects. In rewriting the following legend, except in expressions where obsolete forms of English have to be employed, I use freely words that convey more clearly the interpretation of the Tlingit thought.

The Purchase of Absolute Right to the Eagle Emblem

“My lad! You ask me to tell you by what means the Eagle became the object of our pride. I cannot blame you for not knowing the main source of this pride because I know that your family were always modest and refrained from telling you, at an early age, anything which might cause you to have a feeling of superiority over your fellow men; but you have now grown to manhood and it is time for you to know why you bear the name Stuwuka.

“I myself spent all of my young days in your grandfather’s house; Shot-hitch (Shotridge) had many men under his authority but I was always his favourite. Thus I had the privilege of learning the ways of a nobleman as well as the true circumstances of the foundation of our party. But I never like to tell these because those of us who have given so much for our own cause cannot bear the thought that that which was uppermost in our minds is no longer consonant with the spirit of modern times. But this is true to the prophecy of Sana-haet (God of Storm), who appeared in a dream to a virgin to give his warning: ‘In sooth, new things will come and the old will pass whence they came. Thy people shall leave the old and take the new for that which thou now honourest shall be deemed unfit for that which will come forth from time.’

“From the day of creation we have been enlightened by intelligent dreams. Thus our walks in life, more or less, were guided by them. But forgive me, my lad, I have wandered away from my story.

“In truth, from the beginning the Eagle ranked high in the esteem of our party. But once ambitious men began, what was there to hinder them? The Eagle was put on a hat in one town and perhaps on a ceremonial staff in another, each assuming its right to ownership, a right which had derived its origin from a myth of an ancestor who fed the eagles when distressed by famine. But you yourself have learned, lad, that an important object cannot be acquired merely by feeding fish to the birds.

“Thus the Shungoo-kaedi went on, very much contented with their idea of virtue, although well aware that the Tsimshian Taequedi were then claiming their own Eagle as the most important object in the Tsimshian land.

“In the meantime your own ancestor, Youwok, grew into manhood. The man, indeed, was one born for a purpose and he never failed in his mission; possibly he was one who would now be spoken of as lucky’. Even while a youth the good goddess of fortune was constantly by his fire. It seems there was nothing that this man could not have; all sources of riches yielded to his bidding. Why was this man successful? It is said that it was the rule of his early manhood to serve his fellow men and his generosity was limited only by his physical strength and ability.

“Thus Youwok became a man of wealth at an early age. But for a time he did not know what to do with his great amount of property. It was not then as it is now (1915), when there are candy, gold teeth, neckties, and whiskey for which money can be spent freely. A foolish young man now should not wonder why he follows a dog-trail in life; he has nothing and merely looks for a bone that someone may cast away. But here I go away again from my story.

“It was generally expected that the young chief would use his great wealth in placing himself in a high station in life. He consulted men of sound reasoning and they all advised him according to the current customs of that time. One man perhaps suggested that he call together great men of other towns and in their presence bring forth his daughter and put a mark upon her to bear throughout her life. [In the coming-out into society of a woman of caste, the lobes of her ears were perforated during the ceremony and pendants, indicating the rank of the wearer, were inserted.] Another suggested this and another that but all these ideas did not find comfort in the mind of this modest man.

“One early dawn, in his sleeping-chamber, Youwok talked to his wife. Possibly the woman complained of being kept awake by her restless husband and they were heard to say :

“‘What can be in your mind-vision to cause you to be so sleepless?’

“It was the Eagle. It seemed to take a firm hold on my mind and as much as I tried I could not sleep after it entered there.’

“‘What sort of an eagle should so take a grip on your foolish brain? You have been dreaming of the poor old bird that we once helped in landing his salmon.’

“The woman knew well the working power of her husband’s mind and that he was not the kind to be wasting thoughts on a fisher-eagle but, like most cherished young wives, she wished to make fun of her beloved husband.

” That morning, before the first meal of the day, the local council of the Shungoo-kaedi sat by the morning fire of Youwok, nodding their old heads up and down as a sign of their approval of the plan which the young chief laid before them. After a long silence an elder spoke up:

“‘You have spoken that which is now fixed in your mind; who is there to change it and tell the outcome of it? But the goddess of fortune is always known to be present wherever a noble mind forms the destiny of man. Therefore, Youwok, go and follow that which your true mind dictates and may this same good goddess of fortune smile on you in your undertaking.’

“The question of the Eagle emblem was ever uppermost in the minds of the councilmen, hence the elder spoke their unanimous approval.

Museum Object Number: NA8507

Image Number: 12625

“Our party, at that time, was residing at Clay-point Fort [the first settlement of the northern division of the Shungoo-kaedi, on the shore of Icy Strait] and it was from that place that Youwok put his canoe in the water and paddled away to the land of the Tsimshian [northern British Columbia]. . . . No, indeed, he was not alone. It is by custom that only the main canoe of an important party is mentioned. The young chief required two great canoes merely to carry the property that he took along to offer in exchange for the right to the Eagle. Yes, there were many other canoes. They say it was something like a great war party.

“They were skillful paddlers, those old-time men. It was then not as it is now, when one can take his bag and walk onto a steamboat and, while enjoying a soft comfortable bed, arrive at a great paddling distance. It is all wonderful, this new life, but such a soft life has much impaired men’s abilities. Who is there now with a mind firm enough to paddle to the other end of the world in order to satisfy the need of his people? Indeed the land of the Tsimshian is at a great distance. I have known just such paddling myself when I went on one of Shot-hitch’s visits thither. But it was not too far for a man of determination.

“So on paddled the Shungoo-kaedi braves as each stroke drew them nearer to the object of their desire. The party made a pause at this and at that town and in each a wish for their speed to success was expressed. I think it was from among the Tongass division of our party that an important person was taken aboard and it is said that this was the man who performed the office of interpreter between the Tlingit and the Tsimshian people.

“Ku-haedgu, the great Tsimshian Tae-quedi chief, resided at Git-gahtl, the old town near the mouth of Jin-heen [Skeena River], where our ancestors resided for so many generations. In the hands of this man lay the fate of the Shungoo-kaedi Eagle.

“‘It may be that Ku-haedgu himself does not know that we now have made the Eagle an object of importance in our own land, or possibly the man is well informed concerning the former relationship of his people and ours, for there has been no record of an adverse attitude on the part of the Tsimshian towards our free use of the object.’ Such were the thoughts of our men as their party approached the land of the Tsimshian.

“The Tsimshian Tae-quedi are a people between the Tsimshian proper and the Tlingit. Love for a fair woman has always been held responsible for a man’s being half of that people and half of this. Such was the origin of our friends here and, regardless of the power of the Tae-quedi proper, who made their first settlement at Tongass, this division had increased and, through intermarrying with their immediate neighbours the Tsimshian, had developed into something like an independent nation. Who is there to rebuke such a state of affairs? There is at this moment sufficient evidence for the belief that another nation, made up of persons who are half European and half Tlingit, is to come forth owing to careless affection. Such is the destiny of the true Tlingit.

“From time unknown it had been the custom of a party, on an important mission, to halt at the approach to its destination and prepare itself for a reception. Thus, the sun being yet high above the horizon when the Shungoo-kaedi party arrived at the approach to Git-gahtl, a camp for the night was called here. By a great fire that evening, each man spoke forth that which he had formed in his own mind and from all these thoughts was arranged an oration to be delivered in introducing the mission of the party.

“The daily life was well begun when the arrival of the Tlingit party was noted at Git-gahtl. There was a confusion—this house and that were thrown open and from within the inmates rushed forth, as in response to a call of alarm. Meanwhile, in the manner of a peace party at the end of a great war, the arrivals lay afloat in the presence of the crowds of people that gathered in front of the town. All at once the clamour of excitement was hushed, and a voice was heard:

“Which of our friends have thus journeyed hither to honour us with this unexpected visit?’

“In answer to the inquiry the spokesman of the visitors spoke:

“‘From Clay-point Fort these thy descendants have journeyed to thy presence.’

“And then the speaker continued and delivered his well-rehearsed speech. Behold, my lad, I am no longer young and my own grandfather was even older than I am now when he recited to me this old story and I forget even important things. Hence, I can repeat only the important parts of the speech that was given there.

“‘My grandfather Ku-haedgu,’ the speaker began.

“‘Thy grandfather would listen to thy words,’ a voice answered.

“‘What is foremost in a man’s mind when he realizes, when confronted with a duty which no man could avoid, that he has reached the limit of his knowledge of life? Through want of a plain path he is confused. Indeed, a man in such a position is once more an infant who cries out for his wants; he may cry for that which is good to the taste, he looks to some one whom he knows to supply these wants, and he is made happy through affection. It is in like manner, with the feeling of an infant, that thy grandson Youwok has come to thy presence; he craves not that which is good to the taste but that which is the desire of a man.

“‘What is there to hinder a man’s progress when he journeys on a right trail of life? He is bound for the desired end. But he who sets forth to find must make a mark by which those who follow may be guided. Thy grandchildren, from their land, have now set forth upon this trail of life and are determined to reach the desired end. In thy hands, 0 chief, lies the object by which these, thy descendants, will bear in mind the Great Shell from which they came. Man knows no honour greater than that which these thy grandsons would bestow upon thee—the privilege of fulfilling the desire which is uppermost in their minds.’

“The purpose of the Shungoo-kaedi journey thither was no trifling matter; there was not a town in which this could remain unknown. Therefore even the youths at Git-gahtl understood the meaning of the speech. During the brief silence that followed there were messengers who rushed here and there, apparently delivering some whispered opinions.

“‘Thou nobleman, thy grandfather has heard thy noble thought.’ And here the speaker turned his face and called out some names:

“‘. . . Indeed, we have been honoured by the visit of the noble. Go thither! Let these your friends come to the warmth of our fires; they must be fatigued by their long journey.’

“In response to the call a group of young men came forward, and the baggage of the visitors was immediately carried away to different houses. But there were two canoes, each bearing a full load, well manned, still afloat beyond reach. After the other canoes were emptied and pushed aside, Youwok stepped ashore and, empty-handed, was led to the abode of the town chief.

“On the upper dais of the great room stood our ancestor You-wok. And there before him, within those walls, was a little world of wonder. The Eagle appeared on all sides; the great bird was carved, in various characters, on the house-pillars, the house-screens, the retaining timbers, and on the many chests. Here was, indeed, the House of the Eagles. For a moment Youwok felt sad, not because of disappointment, but because he thought of the comparison between this display and the style in which the object was shown at his own home. He thought of the original Eagle (page 377) of his ancestors which had been borne through so many changes of life; how small it seemed now! Then he was aroused by another thought. Insignificant as it might seem, this piece had been a cause of the foundation of his party.

“From his seat at the rear of the huge fire rose Ku-haedgu, the great chief. Who is there to imitate the manner of such a nobleman? Like the peaceful flow of a mighty river his words were spoken and these could not be turned back. They say the man was not of great stature. The corners of his noble forehead were like bays and a great beard hung down upon his chest. What a character! I often wonder why our own men never wore such a sign of distinction. I myself, unconsciously, pluck out the hairs as soon as one appears on my chin. With open arms he pointed to the seat he had just vacated and spoke:

“‘My grandson, welcome to the house of thy grandfathers, and here is thy seat. Who is there to sit in the Eagle House with more grace than thou?’

“Then Youwok was surprised; this was, in truth, a turn of affairs contrary to that for which he was prepared and there remained

no way in which to offer his well-rehearsed speech of presentation. He had planned to offer his own ‘presents’ first, but he was beaten in this. After he was seated, Youwok, in a confused manner, spoke:

“‘In thy house, my grandfather, there is plenty and thou shouldst wish for nothing more. Yet I bring to thy hands some things, not because thou art in need of these things but because they are products of my own land. In those canoes yonder, my grandfather, are pieces of fur that may add more to thy comfort and there are also men [slaves] whom I, personally, have trained to attend to thy wants.’

“On that great face, which was lifted high and moved about as if to make certain that all those present had heard, was a broad smile when Ku-haedgu spoke his acceptance:

“‘In truth, my grandson, when a man is at my age he looks only for that which offers him more comfort. Ha! And thou hast brought me these things? Indeed, thou hast come at an opportune moment; henceforth I shall feel secure against man’s pity when I take the seat of the aged.’

“Again the lord of the town looked about and called out the names of his chosen men:

“‘. . . Go, fetch these things that my grandson has brought for me.’

“When the things were carried in, there were bundles of various sizes, of fur of the sea-otter, beaver, marten, fox and ermine. There were also bundles of moose-hides and behind this great pile of property stood, in order, a well-selected group of young slaves; they say these were one count [twenty] in number.

“In those days the exchanging of important things was done in a respectful manner. And every service was performed in like manner. A man of high character was never known to name or set a price upon his skill or labour and it was according to his own sense of honour, too, that a man expressed his thanks. But now, if the iron dollars are not sufficient in number, we cannot get that which we desire.

Museum Object Number: NA9468

Image Number: 12606

“A year, perhaps, had passed when our party called together people from other towns to celebrate the dedication of the new Eagle House at Clay-point Fort. The last ceremony was then drawing to a close, each of our men had sung his song [term for offer of contribution], and it was about dawn of the next day when You-wok stood by the great pile of his own property. On his head was placed the new Eagle Hat—the same one there before you. In concluding his speech, before the distribution of the main offering among the guest party, personal names were bestowed on those members in whom all hopes of progress were then centred, names to commemorate important events which had occurred in our affairs. At last the spokesman announced the new name for the young chief:

“‘Henceforth this man shall be no longer Youwok but he shall be called Situwu-kah [Astute Man]. Tae-quedi! Naeh-adi! Naes-adi! Yan-edi! and Chukan-edi! [Original clans.] In your firm grasp is now the object of your desire. Who is there to dispute your claim to its ownership when ye bear forth into life the Eagle? But before we raise our heads in pride it is proper that we give honour to the noble mind which is the source of one’s pride. We have learned that where even a crafty mind fails, a generous mind succeeds. Surely there never was a decision made with more wisdom than that of this man when he decided to clear away the feeling of embarrassment.’

“Now, my lad, I have conveyed to your mind the source of our pride and you bear that same name, the mention of which brings back to the mind of a true man the history of its origin. Many men bore this name before you—noblemen, indeed, who did honour to it. And when I hear about your journeys to the far corners of the strange world, I would, only in silence, invoke some unseen power to grant you success and bear the name clear of disgrace and shame.”

The Tlingit definition of the term Situwu-kah does not exactly correspond with “wisdom”, which the name is supposed to imply, for “wisdom” in Tlingit cannot very well form a personal name, and the use of the allied word “astute” is more convenient of pronunciation. Hence, the employment of Situwu-kah (Stuwu-ka), regardless of its native definition; but the true interpretation of the name is “Wise Man”.

Modern influence has now silenced our native life because of our nonconformity and this old hat, likewise, has ceased to inspire patriotism. Hence we can do no more than recite the story of its origin.

The ceremonial hats and other esoteric objects pictured and described on the following pages form a part of the large collection of Tlingit Indian specimens secured by the author on his last expedition to Alaska for the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM. These, together with the best of the other objects, are exhibited in the Tlingit Hall in the west wing of the first floor.

The Whale Hat

Ceremonial hat, woven of roots of the spruce tree. Painted on it is a design representing the Whale, an emblem of the leading clan of the Tlhigh-naedi moiety of the Tlingit people, and signifying greatness. The carved wooden piece, fixed on the top of the crown, with locks of human hair for ornamentation, represents the fin of the sea animal.

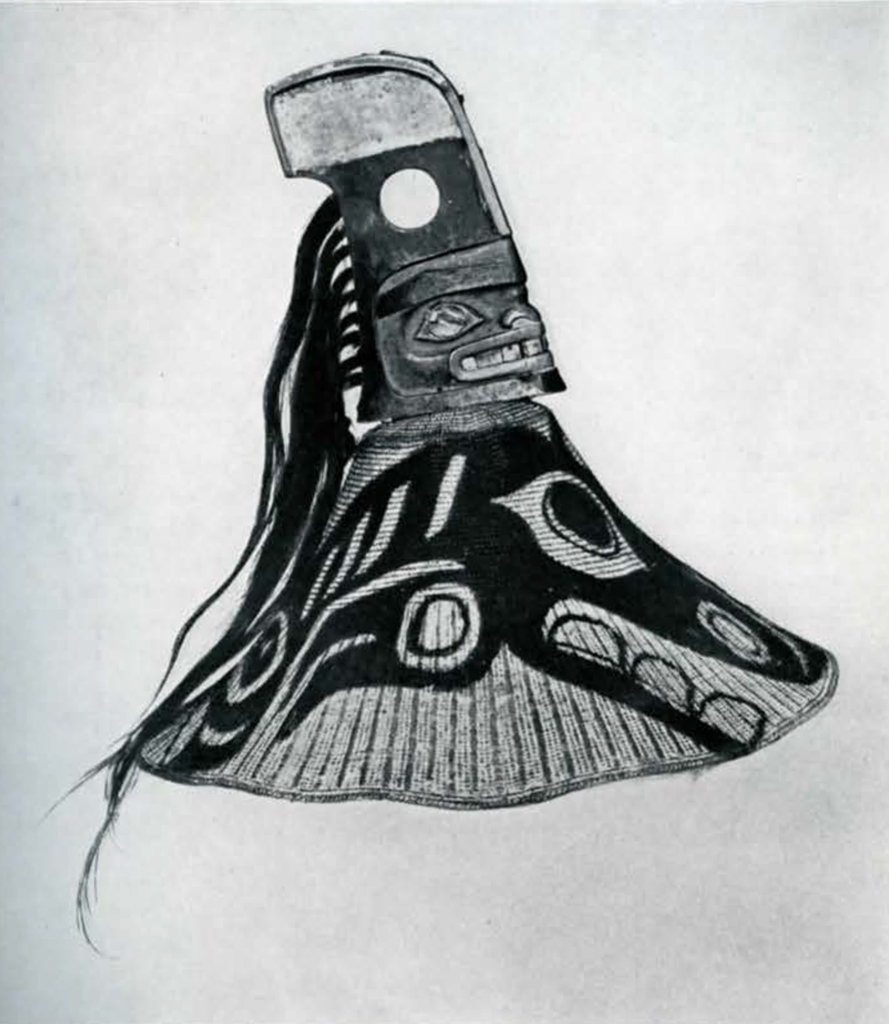

The Raven Hat

Ceremonial hat, carved of wood to represent the “Raven of the Roof”, a characteristic emblem of alliance of one of the important clans of the Tlhigh-naedi moiety of the Tlingit people. Native copper is used for ornamentation, and the “top-stock”, which represents the number of ceremonies in which the old hat was brought forth before the public, is woven of roots of the spruce tree. It is like a cylindrical case of seven circular boxes, connected by constricted tubelike openings so that it can expand and contract like a bellows.

The true likeness of the bird, in this specimen, was intentionally ignored in order to make the object appear different from the original Raven Hat.

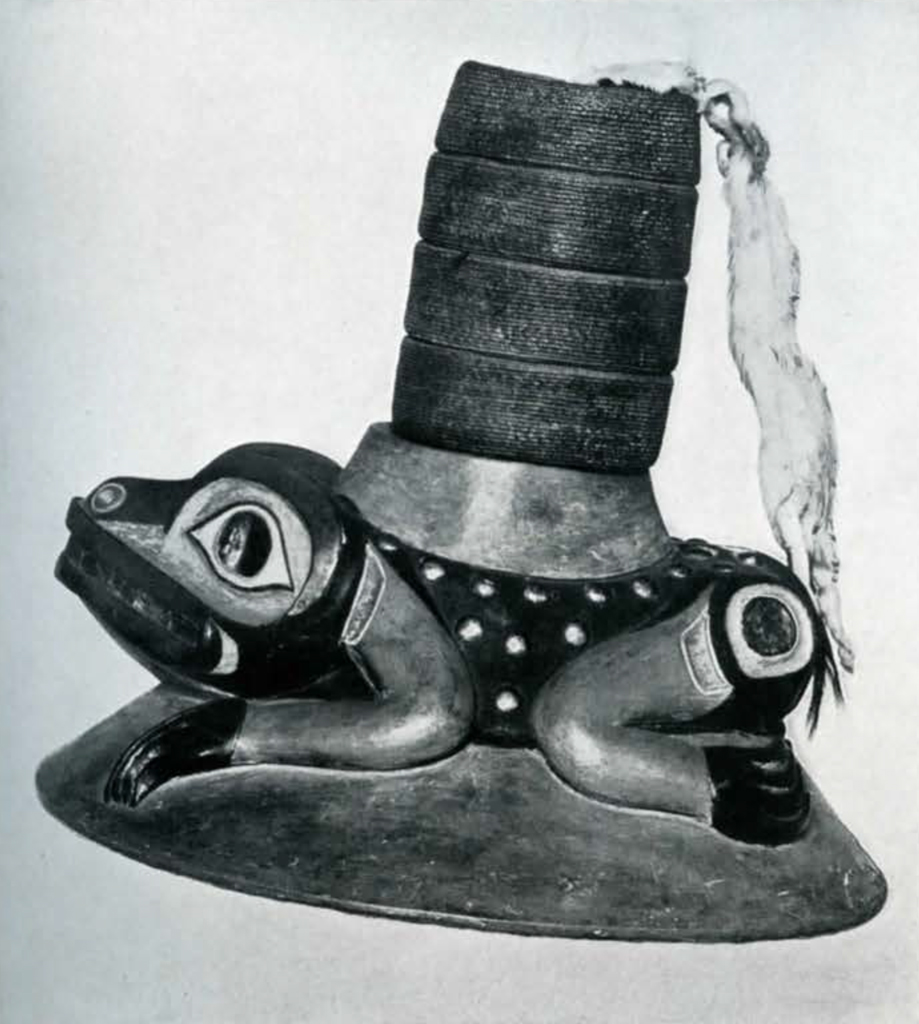

The Frog Hat

Ceremonial hat, representing the Frog, an emblem of the Kiks-adi clan, a subdivision of the Tlhigh-naedi moiety of the Tlingit people. It signifies persistence. In their early history the Kiks-adi, like frogs, were unmoved by all the abuses of other parties, but steadfastly continued in their development. Thus came about the adoption of the amphibian, regardless of a possible connotation of loathsomeness.

The specimen is carved of one piece of maple wood, ornamented with copper and brass, and pieces of blue abalone shell are inlaid as teeth and eyes. The “top-stock” is woven of roots of the spruce tree.

The Eagle Hat

Ceremonial hat, representing the Eagle, an emblem of the Shungoo-kaedi moiety of the Tlingit people signifying determination. The specimen is carved, in one piece, of the root of the red cedar and ornamented with human hair. The designs, carved on either side and inlaid with pieces of abalone shell, represent the wings, while those on the front part of the crown are the talons of the bird.

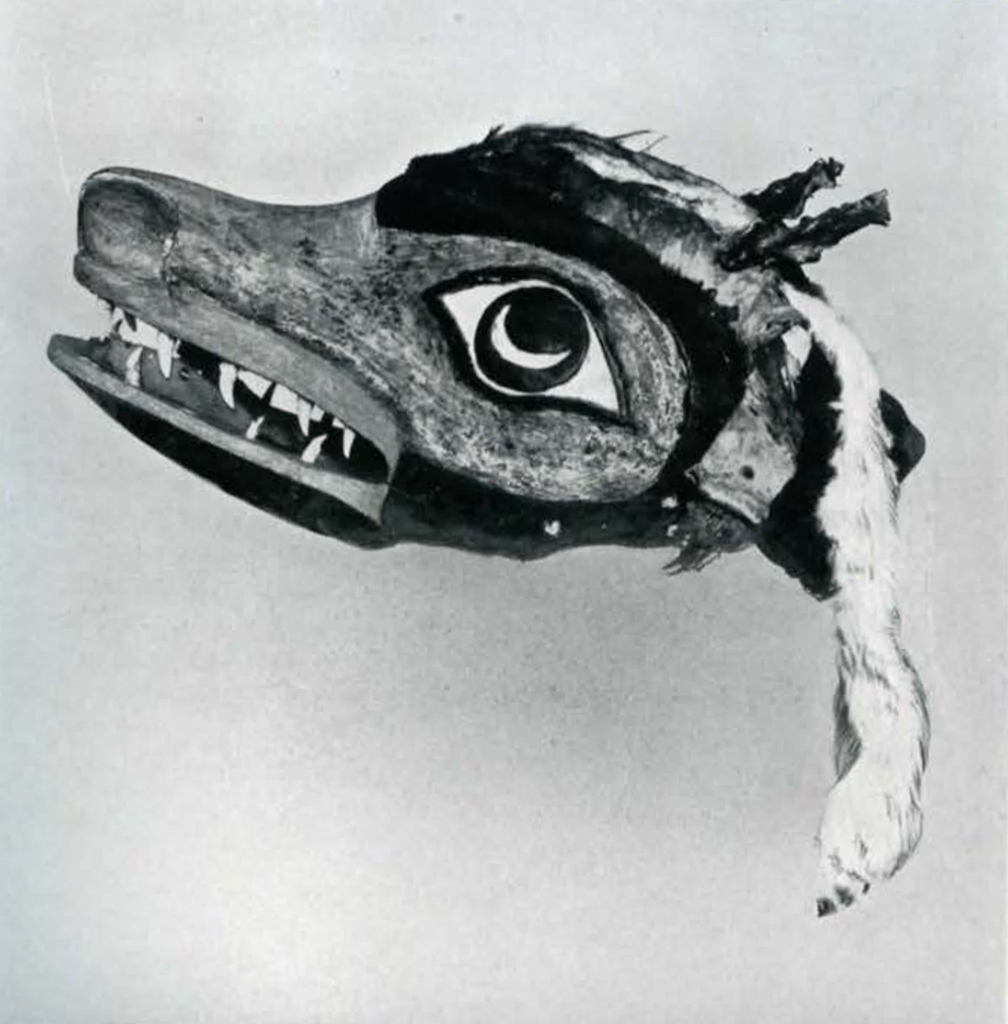

The Wolf Helmet

War helmet, representing the Wolf, an emblem of the Kaguan-ton clan, a subdivision of the Shungoo-kaedi moiety of the Tlingit people. It represents courage. The specimen is carved of wood and crowned with the scalp of the wolf, with the ears of the animal preserved. The skin part of the scalp, however, has been partly destroyed by insects. The teeth are also those of the animal.

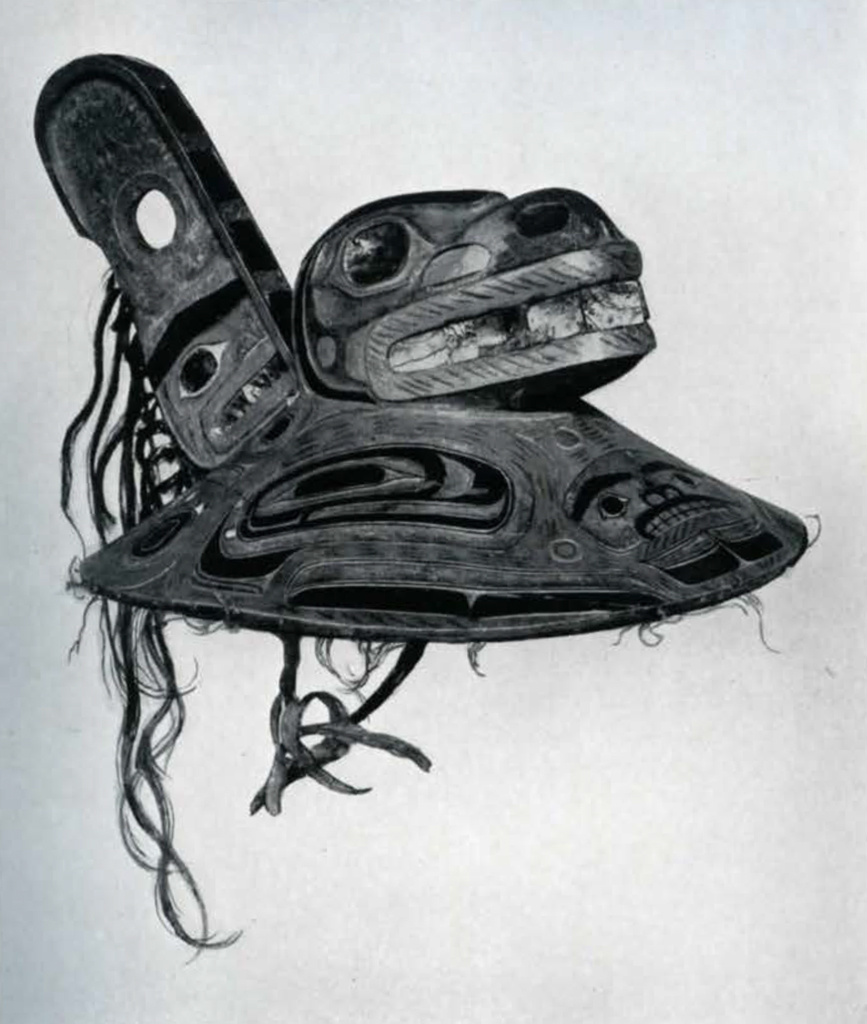

The Killer-Whale Hat

Ceremonial hat, representing the “Noble Killer”, an emblem of the maritime power of the Kaguan-ton clan, the most powerful of the Shungoo-kaedi moiety of the Tlingit people. The characteristic name was thus applied to distinguish the object from the original “Killer-whale”, founded by a humble subdivision. The specimen is carved of wood. It is inlaid with pieces of blue abalone shell and the fin part is ornamented with locks of human hair.

The Eagle Staff

Ceremonial object, representing the Eagle, an emblem of determination, and belonging to the Shungoo-kaedi moiety of the Tlingit people. The object is said to be the original piece which the people carried when they took possession of the region, after which it was used as a crest on a ceremonial headdress. But after the making of a hat representing the same object it served as the headpiece of a ceremonial staff, whence the final name.

The specimen is carved of a fine-grained wood and was always protected by a case of woven bark. The human hair ornamentation, which once hung low about the effigy but is now worn to short stubs, consists of locks taken from heads of slaves who were slain during the ceremonies in which the object was brought forth before the public.