ALTHOUGH there has been extensive archaeological work carried on in the Southwest in recent years, much still remains to be accomplished, particularly in southeastern New Mexico, and across the boundary-line into Texas. With the hope of trying to fill in some of the missing parts of the picture of this area, work was undertaken, during the past summer, along the southwestern and eastern slopes of the Guadalupe Mountains, the principal object being to ascertain whether any evidence of Basket-Maker culture could be found there. The work was conducted under permission granted by the U. S. Department of the Interior.

Caves have not only furnished shelter to man against the elements and protection against his enemies and wild beasts, but they have also been utilized as storage and burial places since remote times. The caves of the Southwest, on account of the very dry climate prevailing, offer particularly favorable places in which to find material evidence of the early culture of that region. The dirt and dust is so dry in these caves that baskets, sandals, and many other things are preserved in a most remarkable manner, thus allowing one to draw an unusually complete picture of the life of these early people.

The earliest people in the Southwest, of whom there is definite knowledge, are the Basket-Makers. This name was applied to them by Richard Wetherill and his brothers, when, in 1889-90, they found remains of a people strati-graphically older than the Cliff-Dwellers, whose ruins they were exploring in Grand Gulch, Utah.

There are two distinct cultures generally recognized in the region spoken of as the Southwest, namely the Basket-Maker and the Pueblo; this latter group also includes the Cliff-Dwellers. The gap between the Basket-Maker and the Pueblo has been narrowed by what is known as the post-Basket-Maker and the pre-Pueblo cultures.

Basket-Makers of Period I are thought of as nomads, with whom hunting predominated, followed in Period II by the introduction of corn, supposedly from Mexico. During this time they began to dig pits in the floors of caves in which they stored their grain and also buried their dead. Crude sunbaked vessels were developed also about this time. As agriculture became better established and they became more sedentary in their habits, they began, in Period HI, to enlarge their pits or cists, lining them with stone slabs and covering them with poles and brush, from which pit-dwellings later developed. At the end of this last period of the Basket-Makers, true pottery was introduced and later highly developed by the new group who appeared on the scene.

The Basket-Maker was long-headed and did not have an artificially deformed skull as did the Pueblo peoples who followed him. As his name suggests, he made excellent baskets. He also made sandals of yucca leaves and yucca cord; well made twined-woven bags, fur-cloth robes, and instead of the bow and arrow he used a spear-thrower. He had no cotton and apparently did not domesticate the turkey, both traits appearing later.

This gives a brief sketch of the early people with whom we are here concerned. It leaves out the question of chronology, however. Dr. A. V. Kidder, in his “Southwestern Archaeology,” assigns a date to the Basket-Maker of 1500 to 2000 B.C. and this date appears to be generally accepted as conservative. Dr. A. E. Douglas, by a study of tree-rings, has developed a time-chart by which he has been able to date definitely many Pueblo sites from log-beams recovered from the ruins. His method will, in time, furnish further data on which to base an accurate chronology.

The Southwest from an archaeological point of view differs somewhat from the geographical division of our country, though the former continues to enlarge its boundaries as new culture-sites appear. At present this region seems to take in Arizona and New Mexico, the southwestern part of Colorado, most of Utah, eastern Nevada, and the western edge of Texas. Across the border it covers also a part of northern Mexico. We are concerned here with only a very small part of this large area, namely the southeastern part of New Mexico and just across the boundary line into Texas; more particularly with the country about the Guadalupe Mountains.

Image Number: 13221

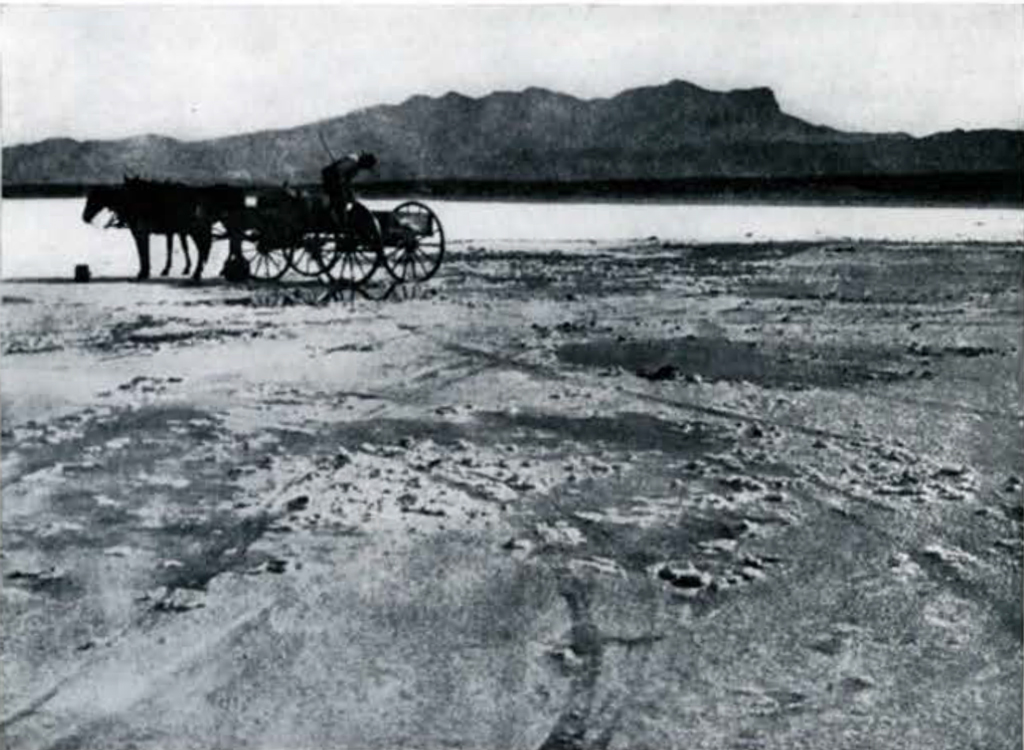

The Guadalupe Mountains [Plates XXVI and XXXVII] are an extension of the Sacramento Mountains southward across the New Mexico-Texas line into Culberson County, Texas, where they rise abruptly to a considerable height from the arid plains below. The peaks at Guadalupe Point rise more than 9000 feet above sea-level, the southernmost one terminating in an almost sheer precipice of limestone 1500 to 1800 feet thick. This limestone, according to Darton, is known as the Capitan limestone and is hard and massive, and merges northward in New Mexico with the Chupadero formations. Southward from Guadalupe Point, the Capitan limestone ends and the sandstone of the Delaware Mountains begins and extends on further into Texas.

On the west and southwest side of the Guadalupe Mountains [Plate XXXVII, 2] are salt lakes surrounded by white sand dunes of gypsum. On the east the land slopes gradually eastward and merges with the Texas plains. Both sides, however, are cut by canyons which serve to carry off the torrential rains occurring in this region at times. Mostly the canyons are dry; occasionally one finds a canyon in which there is a perennial stream, such as the upper part of “Last Chance Canyon” [Plate XXVII, 2] on the east slope of the mountain.

Except near the top of the mountains, where the growth of spruce and pine and long grass is a welcome sight, and in spots along the canyons favored by ground-water, the country presents the usual semi-desert aspect of the Southwest— innumerable varieties of the cactus family, scrub-oak, pifion, cedar greasewood, sage and several varieties of yucca. Near the top and along the bluffs of the southern end of the Guadalupes there are a few mountain sheep still to be found. There are also deer, grouse, Mexican quail, occasionally a wild cat or a panther, and countless rabbits.

Image Number: 13219

Whether the country below the top of the mountains, sloping away to the flats on the west side, and towards the Pecos River on the east, was always as dry as at present, is hard to say. Old settlers, about there, are inclined to say that climatic conditions are dryer now than they used to be; but old settlers everywhere are apt to comment unfavorably upon the weather. There is some evidence that where the grass has been grazed off by goat and sheep, the wind has gotten in its work and turned parts of the country into a veritable desert. On the other hand, through the tree-ring work of Dr. Douglas, it has been definitely established that, during the earlier Pueblo occupation of the country north and west of this locality, periodic droughts occurred, some of which were so extended that they were, undoubtedly, a contributing cause to the abandonment of these Pueblo villages.

Whether conditions were as dry as at present or not, there is evidence of early occupation of the country on both slopes of the Guadalupe Mountains. in the canyons there are caves of all kinds, ranging in size from the wonderful Carlsbad Cavern to small shelters. Most of them have been more or less disturbed by ranchers and cowboys looking for buried treasure, or by “pothunters.” The old Butterfield trail passed along the Delaware River and close around the base of Guadalupe Point on its way west, and the many stories of “hold-ups” along its route, in the days before the Civil War, help to fire the imagination of these treasure seekers. “Billy the Kid,” the hero-bandit of that region, roamed this part of the country, and through the tales woven about his career, no doubt have helped to keep alive the belief in huge caches of treasure, buried in the caves along this trail. There are also those who “specialize” in the hunt for Spanish treasure. The occasional find of a silver stirrup or a wrought iron bit lends zest to the search. Thus it is hard to find a cave that someone has not been into before you and has practically turned up-side down.

Image Number: 13186

Preparation for the hunt for Basket-Maker caves began at Alamogordo, New Mexico, and a preliminary trip was arranged by Mr. Tom Charles, who is largely responsible for the interest in archaeology in that vicinity, and whose help and friendship I greatly value.

With Demsen Lewis as guide, Mr. Charles and I crossed the Sacramento Mountains and headed for Little Dog Canyon on the west slope of the Guadalupes. The road, if such it could be called, disappeared completely among the boulders of the dry river bed, and brought the car to a halt with two flat tires. We had come about three miles from Mr. Martin Lewis’s place and now walked about four miles further up the canyon to a cave which Demsen Lewis knew about.

The cave was a short distance beyond the point where the canyon narrows into steep walls on either side. It was well hidden by bushes and hackberry trees in front of the entrance, which was some forty feet up the side of the canyon. The entrance was narrow and rather low. Inside, however, it opened into a larger and higher chamber. As soon as we directed our flashlight into the interior we were greeted by a swarm of bats; after smoking them out, the floor of the cave showed signs of recent digging all along the walls. We found no evidence whatever here of occupation, and the same was true of another cave a short distance up the canyon on the opposite side. So we abandoned Little Dog Canyon and returned to the car.

The following day we moved further south across the New Mexico-Texas line to the ranch of Mr. J. A. Williams of Ables, Texas, to whom grateful acknowledgement is made for the cooperation shown by him in allowing us to excavate in one of the caves on his land. In a direction a little south of east, and between his house and Signal Peak service station on the El Paso-Carlsbad Highway, there are a number of deep, barren canyons, and in mast of these are caves of various sizes, some of them used as goat-pens in the winter time.

Image Number: 13222

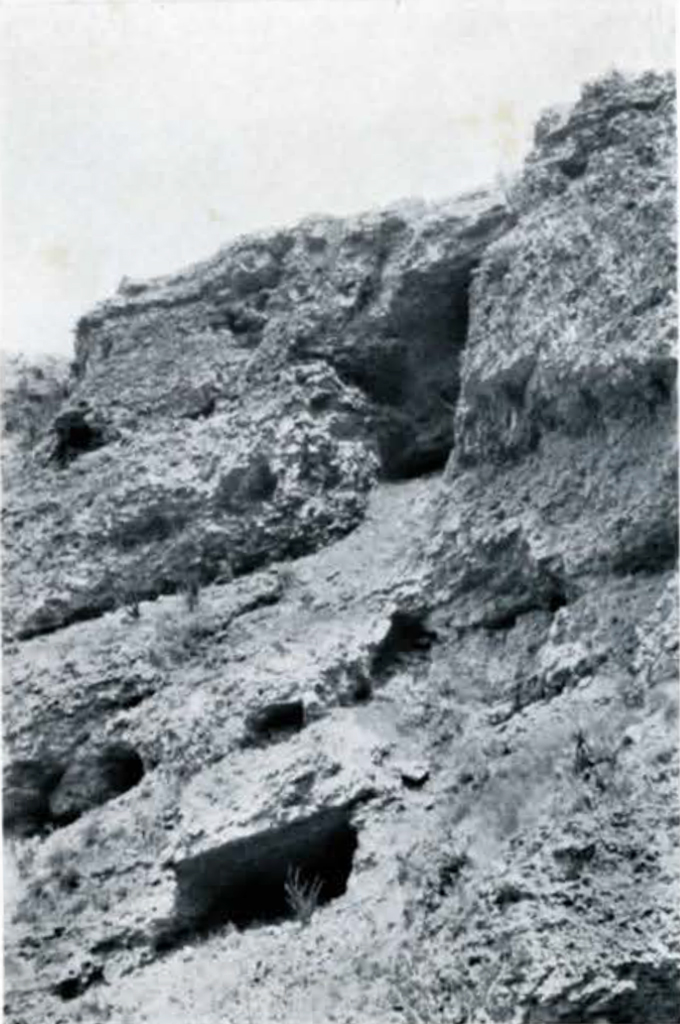

About three miles slightly north of west from the service station, and between here and Mr. Williams’s house is a large cave which looked promising enough to do some digging in, regardless of the fact that it showed unmistakable signs of having been previously disturbed. The canyon in which the cave is located seems to have no name; but sighting directly at the centre point of Guadalupe Peak, the cave was approximately fifteen degrees east of south from the peak. It is in the southwest corner of Section 13, Block 121, Culberson County, Texas. The entrance was some two hundred feet up the left wall of the canyon, facing almost due east, and the walk up to it was very steep [Plate XXXVII, 1].

We returned to Alamogordo to equip for the actual digging we had decided to do at this place. I went back to Signal Peak service station in a few days with Mr. Ray Charles and two Mexicans, making our camp at this point on account of being able to secure water there. We carried to the cave our equipment, including a wheelbarrow, which nearly wrecked the expedition in getting it up the side of the canyon.

When we arrived, Mr. Williams was sitting at the top of the canyon wall on the other side from the cave, with a gun across his knees. He explained that a young man had come on his place some time previously, and had dug up this very cave without telling him anything about it; and having heard that this same man was in the vicinity again, with the same purpose in mind, he was “laying” for him. Although I was in hearty sympathy with his feelings, I was glad he recognized me alive instead of dead.

The cave, as I have said, was fairly turned up-side down, with large holes dug on the right hand side at intervals all the way to the back, and the dirt and rock taken out piled up around the holes like small craters. At the front part of the cave large blocks of stone from the roof had fallen off. From the point of the south wall due north to the opposite wall, the entrance was nearly sixty feet, and from the centre of the entrance to the rear of the cave was slightly over sixty feet. However, the right hand side extended back about a third again as far as the other side. The roof which was quite high at the entrance sloped sharply at the back where there was hardly standing room.

Image Numbers: 13191, 13192

The front part of the cave seemed to be the least disturbed, so we began our excavation there, confining it to the right side of the cave only, leaving the left side for some future time. The rocks kept us busy for some while, and the Mexicans vied with each other in the size of the rocks they could send crashing down the canyon. After we levelled off a place at the front we began working back towards the holes already dug. The dirt was screened at the entrance before throwing it out of the cave, and in this way we recovered bits of cord, bone, spear-shafts, basket fragments and a few pieces of pottery. Clumps of grass had been dug out of some of the holes, excavated before we got there, as this lay around the holes in considerable quantities.

In order to get some idea of the depth of the dirt on the cave floor, we dug a hole six feet deep on the right hand side, near the wall and where there appeared to be no great disturbance. Below the irregular surface were loose stones, dried grass and cave dust; then came twelve inches of white ash and rocks, where there had evidently been a floor level, and where in some places was a kind of packed manure. Below this for twenty-four inches was a compact bard layer of dirt, followed by twenty-four inches of gravel, pieces of stick, pine needles and signs of rats. At the sixteen-inch level were found bits of bone and cord made of yucca fibre. The following are some of the objects recovered:

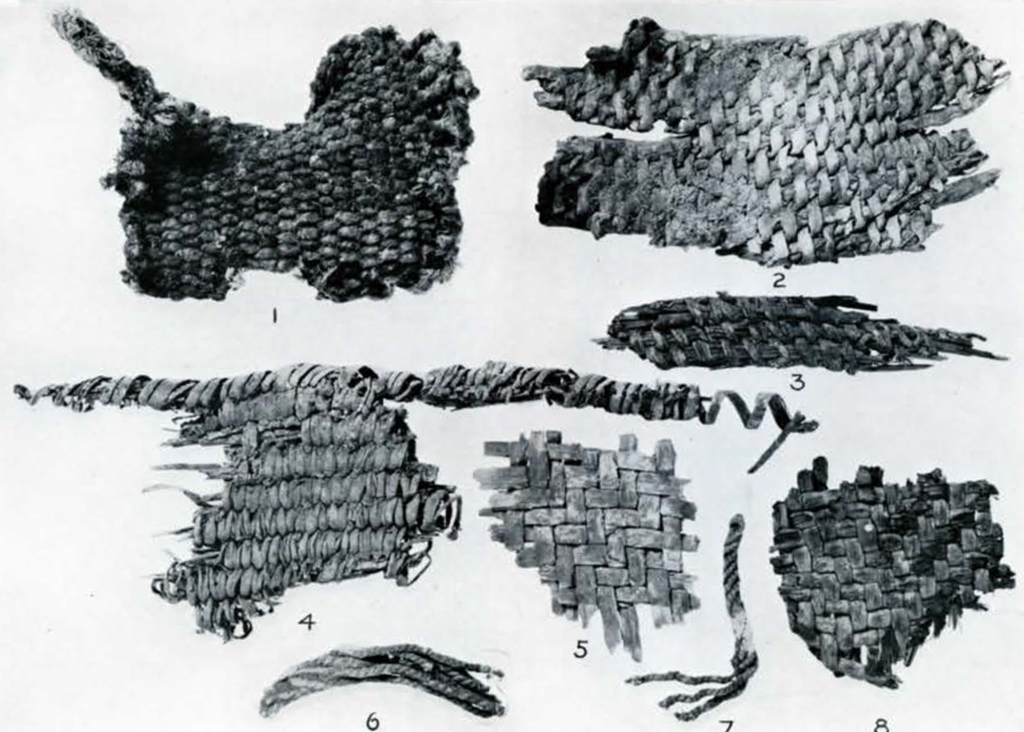

A fragment of heavy, twined-woven cord bag, typical of Basket-Maker work, and with red cord decoration [Plate XXVIII, 1].

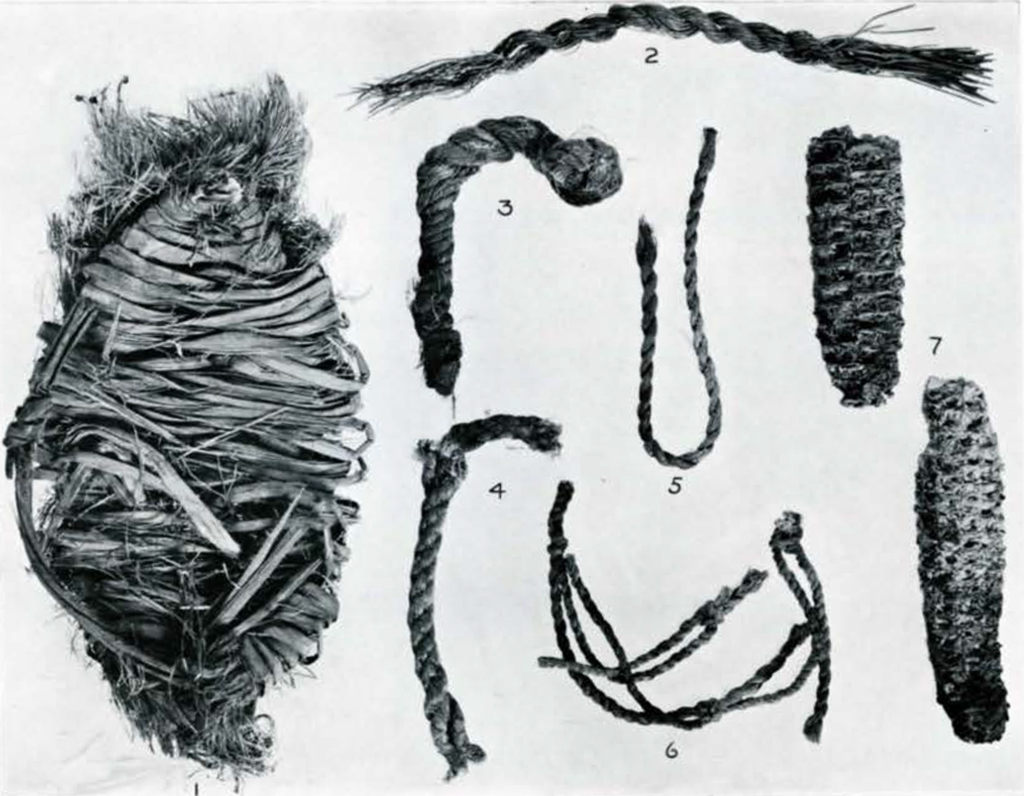

Pieces of two and three strand cord, fringe and various types of cord and netting shown in Plate XXVIII, 6 and 7, and in Plate XXIX, 3 to 6.

Small corncobs shown in Plate XXIX, 7, various knots and loops of yucca leaves, such as were used to bind twigs and splints for making baskets or other objects; a bone awl three inches long [Plate XXXI, 6]; a small object, probably of ceremonial use, made of the dew-claws of the deer, fixed at regular intervals on a small stick [Plate XXXI, 5].

A sandal, six inches long, of wickerwork, made of whole yucca leaves, pointed at both the heel and toe by drawing together at each end the two yucca leaves, forming the warp elements [Plate XXIX, 1].

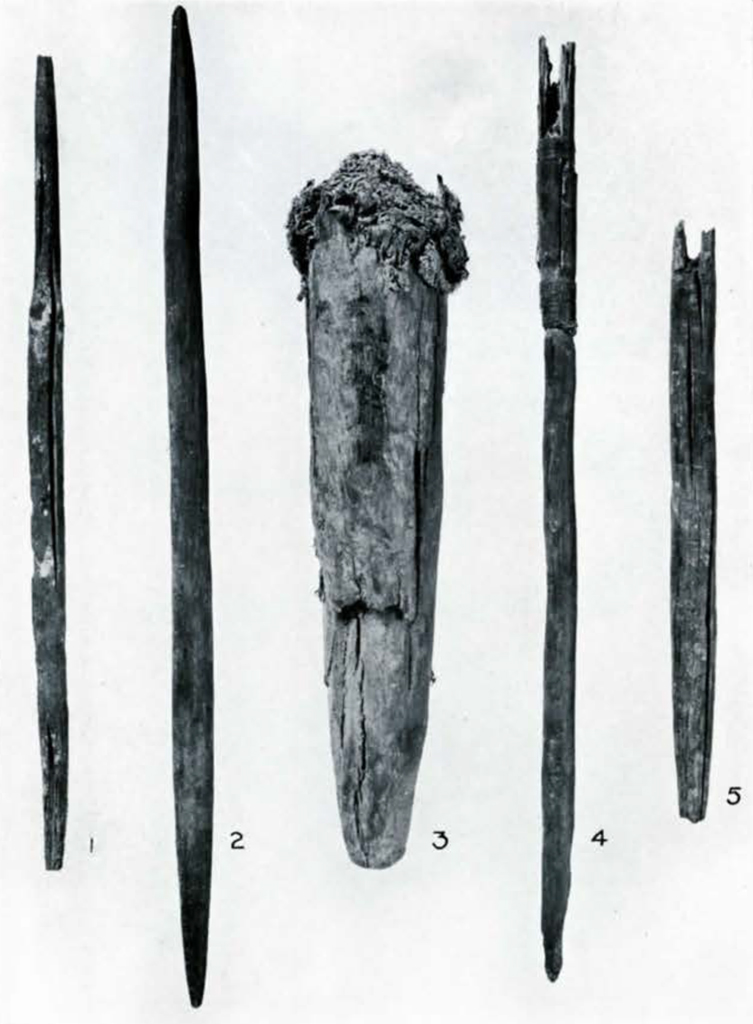

Among the wooden objects are a foreshaft seven inches long, pointed at both ends [Plate XXX, 2]; a wedge battered at the end [Plate XXX, 3]; a bark scoop; and a number of sticks of various use, some with cord markings on them.

Only one stone implement was recovered, a spear-point, or possibly a knife of rhyolite, shown in Plate XXXI, 3.

There were a number of animal bones, such as the skulls of some rodent; deer leg-bones; and a few small bones, and pieces of skull of a human.

A few fragments of pottery were also found, but as they were found in the previously disturbed dirt, no definite level can be assigned to them. They are rather well made, with a fairly coarse sandy binder. Some pieces are of a blackish-gray color, while others are a dull reddish-brown, due to firing; the outer surface quite rough.

It is my understanding that several baskets, a number of sandals, a skull and other objects to a considerable amount were taken from this cave, and are in private hands in Carlsbad, New Mexico.

A second cave on this side of the mountains was also examined; but no excavation was done, and for the very good reason that the cave was in a very inaccessible place. This particular cave is in the northwest corner of Section 46, Block 66, and is also on Mr. J. A. Williams’s land. In an air-line it is located about three or four miles somewhat west of north from his house, but to get to it is many miles further and a long climb up the Guadalupes. It is approximately a mile above the flats and near the top of the uppermost bench of the mountains at this point. To get to it you climb up to the top bench just below the talus sloping from the peaks, following around one spur after another till you reach the canyon where the cave is located. It has to be approached by going above it and then around and up to it from the outer edge, as the wall of the canyon is very steep at this point. It faces almost southwest.

Its inaccessibility accounts for it not having been disturbed. It is very large — much larger than the one just described, with a wide high roof at the front. At the rear, and on the left hand side, is a high-roofed chamber going off at right angles. The dust is several feet thick in this part of the cave and the floor surface is thickly covered with bat guano. The roof was blackened with smoke and also with the excreta of thousands of “daddy-long-legs,” which gives almost the same impression as smoke.

Image Number: 13189

Image Number: 13190

At the right, towards the back of the outer chamber, was a low pile of rocks among which we picked up a piece of knotted fibre such as might have formed a sandal tie. By the opposite wall was a sort of pit which may be what, in that part of the country, is called a “mescal pit.” Not being properly equipped to excavate this cave, chiefly on account of the difficulty of transporting water, we left the cave as we found it; but with the sincere hope of being able to return at some future time to do the work properly. It took us forty minutes to climb down from here to the bed of the canyon, and then we were still high above the flats to the west. On the way Mr. Williams pointed out two mountain sheep to us.

The caves on the east slope of the Guadalupes seem to be more numerous, for nearly every canyon has some. Before doing any excavation work on this side, I spent a number of days, with Mr. R. M. Burnet, of Carlsbad, as my guide, in reconnaissance of the canyons west of here. Without “Bill” Burnet’s able help the results would have been very meager. We went first to Anderson Canyon, where we found a toe of a sandal at the rear of a cave which had not been much disturbed. We came back to this cave later to do some excavation. We also investigated caves in Pine Canyon; but, as we understood that Dr. Mera from the Laboratory of Anthropology at Santa Fe expected to work on the caves in this canyon later on in the fall, we did nothing more than look them over. They all appeared to have been previously disturbed.

Making Carlsbad my base, I then decided to concentrate on the canyons tributary to Last Chance Canyon on the south side, this last named canyon being one of the largest tributaries of Dark Canyon. We stowed our equipment in the back of the Chevrolet and all over Bill’s ancient “T-Model,” and with our force augmented by two energetic young men from Carlsbad, by the names of Julian Shattuck and Norman Riley, who went along to help dig, we set out for the mountains.

We followed the road to Queen, which was a trial and a tribulation, even to the Ford, but we eventually arrived at the top, and surrounded by big pine trees we camped for the night at the Ranger Station at Carson’s Seep. The following morning our objective was Gilson Canyon, another tributary of Last Chance Canyon. We took a roundabout way, going to the upper part of Dark Canyon first and then stopping on the way to get two horses to use in getting down into the canyons.

Gilson is a wild winding canyon with steep sides. We found no caves till we reached a sharp bend where there is a goat camp and where the old cowboy, whose name the canyon bears, lies buried in a solitary grave. There were a number of caves at this point, two hundred or more feet above the bottom of the canyon, some quite large and one with a double-storied entrance. All, however, had been dug into. Several showed signs of water seepage, and since there was no evidence of occupation, we did not consider it worth while to do any excavation. We followed the canyon down to within a short distance of where it empties into “Last Chance.” There were a number of large shelters beyond Gilson Camp, and on the walls of some of them were paintings. At one particularly narrow place in the canyon we found the remains of an ancient still, with a sign painted on the rocks warning federal officers to keep out.

A little discouraged at having gone into dozens of caves without finding any that we considered worth more than a hasty examination, we next decided to head for the country somewhat north of Last Chance Canyon, known as the “Three Forks” country, and which is the upper reaches of Rocky Arroyo. We followed the road which goes past the “H Bar Y” ranch to the point where the three forks come together and where there is a large cattle tank, approximately fifty miles by very bad roads from Carlsbad. From the cattle tank above mentioned, and less than half a mile up the left band or south fork there is a sort of crescent-shaped flat place where the dry canyon bed takes a bend around some sharp spurs. Here in a northeasterly direction along the slope are several caves close together and on different levels.

The larger and upper cave [Plate XXVII, 1] attracted our attention, even though it had been previously dug into in a number of places. It was approximately seventy feet above the flat, with a high opening— some twenty-five feet, and it faced a little south of west. The roof was much weathered, especially near the entrance where large quantities of rock had fallen off, some of which took two of us to shove over the side. There is a double overhang, due no doubt to the harder limestone underneath eroding less easily than that forming the upper part nearer the entrance. At some fifteen or twenty feet in from the edge of the cave, the second overhang begins, and from here to the very rear of the cave the roof slopes back more gradually at a height of about three feet above the floor. The entrance at the second overhang was thirteen feet, seven inches wide.

The previous digging had been done on the right or easterly side of the cave, at least three fairly large holes having been dug and the dirt and rock piled up so that it extended over the whole surface of the floor. We decided to excavate the westerly side. The loose stones and large rocks near the entrance were first thrown out of the cave, and a shelf dug down to a more or less solid level from which we began a trench four or five feet wide following the left band wall. We threw the dirt and stone out as we progressed back into the cave, setting up a screen at the entrance. Some of the holes further in the cave we filled up with the loose rock we took out. The very fine dust was as thick as usual in caves of this type, and we all wore respirators.

Image Number: 13200

Almost at once we began finding animal bones scattered through the dirt at various levels from fifteen to eighteen inches down to three feet, near the wall where pack-rats may have carried them down into some of the crevices. Mixed in at the same general levels, we found bits of cord, fragments of basket, two foreshafts, one apparently a spear foreshaft, and some pieces of gourds. There was no stratification; bones and other objects were mixed together in the undisturbed part of the cave floor that we excavated.

At a point twenty-two feet from the end of the second overhang, or some thirty-five to forty feet from the entrance, we uncovered two baskets, a larger one covering a smaller one. Both were lying quite close up against the side wall of the cave with a foot of dirt over them and six inches of loose rock, fallen from the roof, on top of this. The baskets appeared to have been forced up against the wall by the pressure of the rock and dirt at this point, the floor having a tendency to slope towards the wall. Unfortunately the centre of the top basket had been knocked in by the pressure and was sunken in about five inches below the rim. There was nothing in the lower basket but the dirt which had been forced in from the top and some whitish streaks mixed in with the dirt. There was evidence of a seepage of water, at one time or another, from the wall, so that it was difficult to judge whether this represented a completely disintegrated burial of an infant or not. The upper basket was approximately twenty-two and three quarters inches in diameter, while the lower one was twenty-one and one half inches. The rim of one, decorated with a mountain design, was in good enough condition to show that they were coiled baskets with a two-rod and bundle foundation, with seven coils and fourteen and one half stitches to the inch [Plate XXVIII, 4]. These baskets differed from some of the fragments found nearer the entrance, one piece having an alternating large and small twig foundation, four interlocking coils and nine stiches to the inch [Plate XXVIII, 2], while another fragment has a similar loose coil and a foundation composed of a number of small twigs [Plate XXVIII, 3].

Of the other things recovered, a spear foreshaft lends evidence of a Basket-Maker culture [Plate XXX, 5]. This foreshaft is five and one half inches long with a notched end. The other foreshaft recovered is seven inches long, with a shoulder at one end and pointed at the other [Plate XXX, 1]. Only one bone awl was found, made of deer leg [Plate XXXI, 4]. Bits of cord and reed were also removed, and, in the very rear of the cave, two sandals were found, one fourteen inches under the surface and the other a little above that depth. Both are made of wickerwork and have pointed heels and toes similar to the one found on the other side of the Guadalupes and already described. The smaller one is six and one half inches long and the larger one seven inches [Plate XXXV, 3].

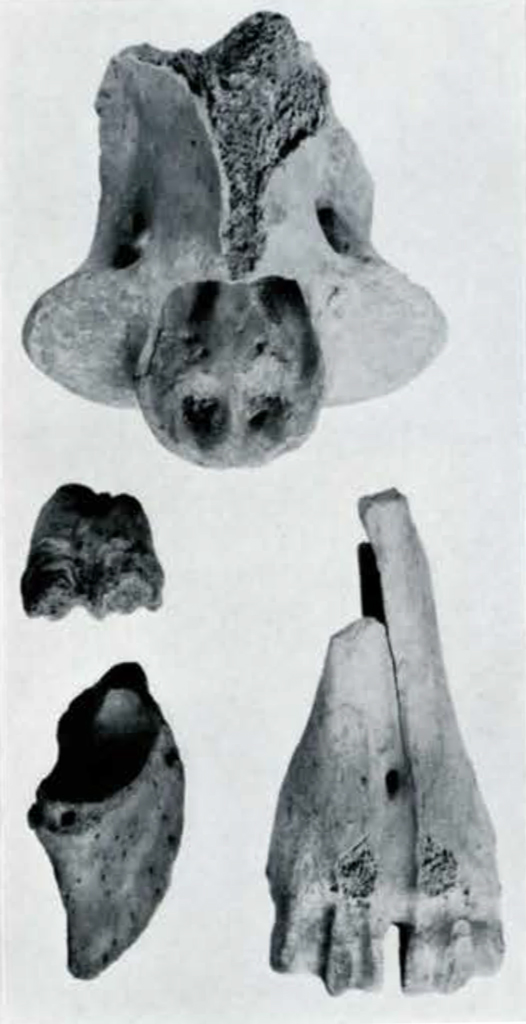

The animal and bird bones recovered from this cave consist of Bison, Horse, Antelope, and California Condor, the latter identified by Dr. A. Wetmore of the National Museum. Dr. Malcolm R. Thorpe, of the Peabody Museum, Yale University, very kindly made the identifications of the animals for me, and I take this opportunity to acknowledge my thanks. The bison has been identified as probably Bison alleni (Marsh), but since none of the horn was recovered, this identification cannot be made certain. Plate XXXII, 2, shows the teeth and a hoof of an adult horse, identified as Equus complicatus (Leidy), while Plate XXXIII, 1, represents a young horse of the same species, both more specifically identified as Equus fraternus. The vertebra of the smaller horse was found lying alongside the upper basket found in this cave. Plate XXXIII, 2, shows the leg bones, teeth, and horn core of Tetrameryx shuleri (Lull). It does not hold, however, that the baskets and other such objects recovered are necessarily of the same age as the bones, which have been identified as Pleistocene, though they were found at the same or even higher levels in the same cave. It is hard to say how these bones got into this cave; there is no evidence that they were carried there by human hands. It is, of course, a possibility that these particular animals lived longer, for some reason or other, in this locality, than paleontologists now believe. In any case, the bones of Tetrameryx are interesting in themselves on account of the fact that they are rare.

Image Number: 13196

Looking like coal-passers, we finished our work here after several days, and, after a bath in some puddles, we returned to Carlsbad to replenish our supplies. The next cave investigated was the one in Anderson Canyon [Plate XXXVI, 1] where we had previously found a sandal toe, and to which we now returned to do some excavating. The road to this canyon leads off to the left at the fork in Last Chance Canyon, the right hand fork going to Sitting Bull Falls. As soon as we came within sight of the canyon we stopped, and from there followed up the canyon to the gate marking the boundry of the National Forest Reserve. The cave is about a mile up the canyon from this point, on the right hand side, and some forty or fifty feet up the wall.

Covered in front by cactus plants and a large ocotilla, or candlebush, the entrance to the cave is hard to see from below. The bed of the canyon at this place is formed of large blocks of limestone, tilted in such a way that you get the impression the canyon runs in the opposite direction to that in which it actually does. Rain-water collects in natural depressions in the rocks. The entrance to the cave faces southeast, and is slightly over twelve feet wide from the point of the southwest corner to the northeast corner. Six or seven feet in from the lower edges of the entrance is a natural pillar which divides the entrance, the left hand side being partly blocked with loose stone. The right hand side, at the edge of the pillar is fifty-three inches high, and the roof slopes down towards the back rather sharply, so that, at a distance of about thirty-five feet from the entrance it is necessary to stoop and then crawl to reach the back of the cave, which goes back another forty or fifty feet. From the point some thirty-five feet in from the entrance the walls also narrow and form a sort of tunnel four or five feet wide, extending to the rear of the cave.

The roof showed evidence of smoke. The floor had been very little disturbed by any previous digging and this gave us some hope of finding some interesting material. As already mentioned, when we had visited this site before, we had dug up a toe of a sandal, near the back of the cave. We had also picked up an arrow foreshaft [Plate XXX, 4] lying on the surface of the floor, back of the pillar which divides the entrance.

We began our excavation along the right, or northeast wall, first, throwing over the edge of the cave the loose rock which had weathered from the roof and was partly blocking the entrance. A shelf was made near the front and we then began a trench about three feet wide, following the wall back, and rigged up a sort of sled from a box we had brought along, in which we put the dirt and dragged it out to the entrance where we screened it before throwing it over the side. The work was very fatiguing, as it was necessary to sit in cramped positions to dig, or even to lie down where the roof sloped near the tunnel at the back, and the dust was particularly thick, so thick at times that our lights could hardly penetrate the clouds suspended in the air.

Two distinct layers of fibre showed up, separated by dirt and. in some places by ashes, to a thickness of nearly four inches. The surface had been practically undisturbed; only a few small holes had been dug here and there. mostly along the right hand wall. There was approximately six inches of loose rock and dirt followed by two or two and a half inches of matted fibre, which was hard to dig out. Then came a layer of three and a half to four inches of ashes and dirt mixed together, followed by a second fibre level of about the same thickness as the first one, under which was undisturbed dirt continuing down to the rock floor.

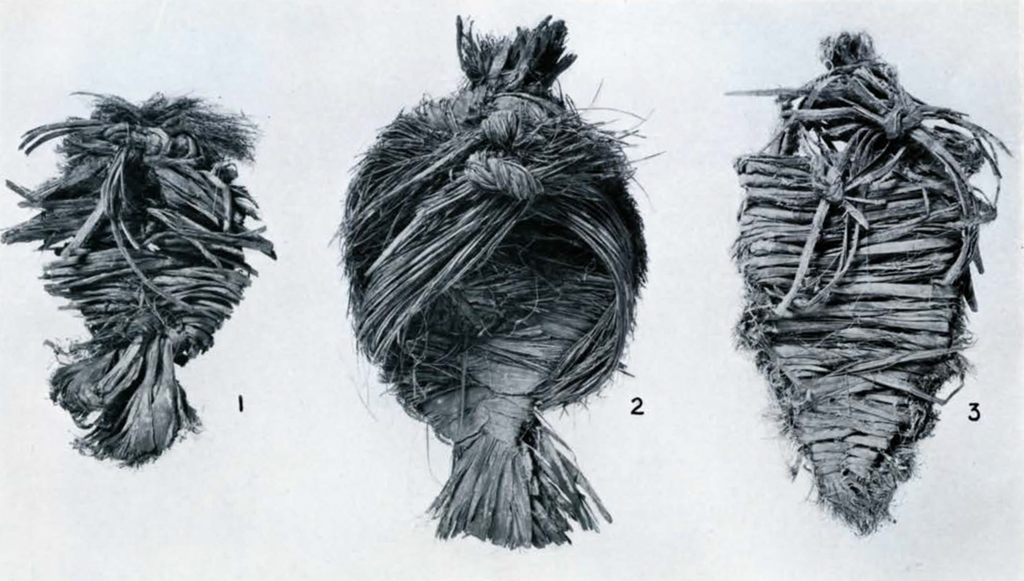

Not far in the cave we began to find bits of cord (see Plate XXIX, 2, for cord made of very tough fibre), fragments of baskets, matting and sandals, mostly at the level of the second fibre layer— fourteen to eighteen inches under the surface. The sandals are rather interesting types. None of them are exactly like those recovered from the other caves described. One type [Plate XXXIV, 1] is made of whole yucca leaves, and is very similar to that type described by Kidder and Guernsey in Bulletin 65 of the Bureau of American Ethnology, except that it appears to be made in the opposite direction. In other words, in the type which Kidder and Guernsey call Type I of a Basket-Maker sandal, the small ends of the warp are brought to the heel where they are tied in a triple knot, whereas in the type shown in Plate XXXIV the small ends of the warp are brought. to the toe and tied, and the ends at the heel protrude. There is also the difference that the warp and the weft both are made up of a number of small whole yucca leaves, instead of one. The sandal shown in Plate XXXIV, 2, is similar but the warps are drawn a little closer together at the heel and do not protrude so far. The larger ends of the weft leaves are shredded out on the under side of the sandal to form a sort of pad. The type shown in Plate XXXIV, 3, is also made of wickerwork, but on a two-strand warp instead of four like the other two examples reproduced on this plate; the toe and the heel are both more rounded. The sizes are: (1) six and a half inches long, including the fringe which protrudes about one and a half inches; the sandal is three inches wide at the widest point; (2) eight and a half inches long; not quite four inches at the widest point; (3) eight inches long and a trifle less than four inches wide. This last type seems to conform quite closely to the Cliff-Dweller type of sandal described by Kidder and Guernsey as Type I, b.

Image Number: 13218

Image Number: 13218

Plate XXXV, 1 and 2, shows two rather interesting types found in this same cave in Anderson Canyon. One is a small sandal for a child, and is only five inches long and less than three wide. The two warp elements are crossed over each other at the heel and protrude to form a sort of “fishtail,” each, however, are made up of several leaves. The leaves forming the weft are woven back and forth once over the warp, the ends coming out at the bottom being cut off close where they emerge, while those coming out on top extend across the width of the sandal.

The sandal shown in Plate XXXV, 2, is a modified form of the type just described. It is composed of leaves of the yucca or similar plant, partly pounded to make them softer. The warp is formed of a number of leaves bunched together and forming an oval, giving two warp elements. The ends at the heel are crossed and extend in the same sort of “fish-tail” just described. An additional feature is that the weft leaves just above the “tail” are shredded and tied over the toe onto the tie-knot, forming a part of this latter and giving the sandal the appearance of those slippers for ladies called “mules.” The sandal proper is only five inches long, the “fish-tail” extending two inches beyond. It is four inches wide across the middle, and would appear to have been designed to cover only the ball of the foot.

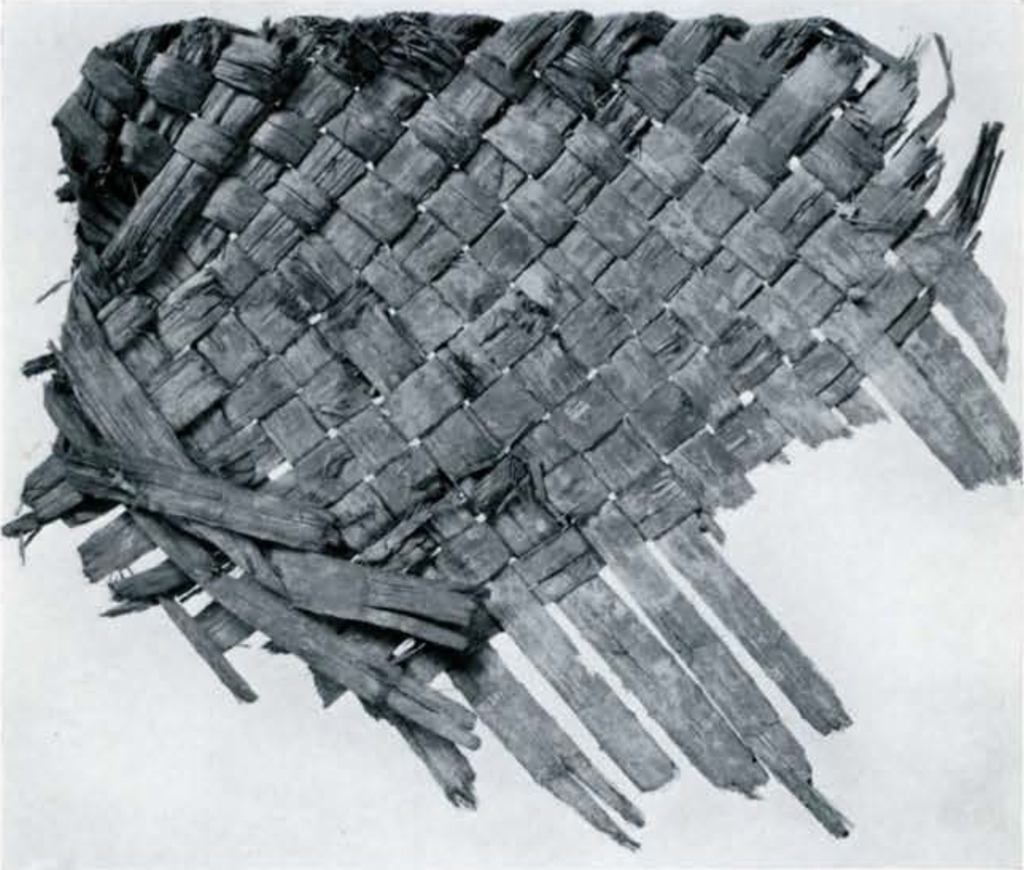

Some pieces of matting were recovered from the cave also. These are shown in Plate XXVIII, 5 and 8, and in Plate XXXVI, 2, the former being twilled work, while that in Plate XXXVI is straight weaving. The method of forming the selvage is clearly shown in the plate.

There were some basket fragments from this cave similar to those described from one of the other eaves, and there were a number of knots of yucca leaves, either parts of sandal ties or binders for tying up splints and twigs for use in making baskets. One stone tool was found here, shown in Plate XXXI, 8. In this same plate, 1, 2, and 3 are points picked up on the flats along Dark and Anderson Canyons.

Beside the caves in this region there are numerous shelters. We found a great many of these in Last Chance Canyon. In front of most of them, or near by, there are round pits formed of small loose rocks which have the appearance of having been burned. Locally these pits are called “mescal pits,” supposedly having been used to cook mescal. These pits are found in all the canyons we went into on the east side of the Guadalupes. They are also found within a short distance of the caves we visited, sometimes in front of the entrance to the cave, where the canyon wall is not too steep, and sometimes below the cave on a flat place in the canyon. These pits vary in size, the largest we saw measuring about twenty-five feet in diameter. We dug into only one of these, finding a few animal bones and teeth and some sherds of a yellowish-gray color. In a few cases these pits were built as part of the shelters, the back part of the shelter forming one of the sides. In only one cave was anything like this sort of pit found, and that was in the large cave on Mr. Williams’s land on the west side of the mountains.

By way of a summary, it might be said that the work of the past summer covered the investigation of a great many caves in the canyons, along the southwestern and eastern slopes of the Guadalupe Mountains, in Eddy County, New Mexico, and Culberson County, Texas. Three of these caves were partially excavated, two of them having been disturbed previously, and the third in Anderson Canyon on the east side showing only slight disturbance previous to our arrival. The other cave on the east side is in what is known, in the “Three Forks” country, as the south fork. The cave on the southwest side excavated is on land owned by Mr. J. A. Williams, of Ables, Texas.

The material recovered from the caves we worked in consists of baskets, fragments of baskets, several types of sandals, pieces of twined, woven bag and matting, a few spear and arrow foreshafts, bone awls, bits of cord and netting, corn cobs, wooden wedges and other wooden objects, a few sherds of undecorated grayish-black pottery, and a number of animal bones, identified as Pleistocene bison, horse and a rather rare antelope, Telrameryx shuleri, besides the bones of some bird similar to that of a large stork. A few human bones were recovered as well.

Certain of the material from these caves resembles very closely specimens of Basket-Maker culture from other parts of the Southwest, notably the fragment of twined, woven bag and spear foreshafts, while other objects found are different. Some types of sandals, though somewhat similar to certain types of Basket-Maker sandals figured by Guernsey and Kidder, are yet enough unlike them to make them different. Certain other types of sandal appear to be very like some types shown in the Peabody Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and said to be from Coahuila, Mexico.

For the present it seems unwise to try to attempt to arrive at any definite conclusion as to just where the culture of this area fits into the general picture. We can only present the evidence as we have found it in the hope that it will add in some small way to the mass of evidence, which is bound to accumulate as time goes on, and, in this way, aid in arriving at a definite conclusion as to what the culture of this region represents.