Lecture Delivered at the University Museum, January 15, 1921

The boundaries of the new Syria where it fronts the eastern end of the Mediterranean agree approximately with those of Ancient Phoenicia. As defined under the terms of the Mandate that gives Syria to France as a Mandatory of the League of Nations, the coast from the Gulf of Alexandretta on the north to a point below the ruins of Tyre on the south is included in Syria, and once more, as throughout the Ages, East and West meet on that narrow ground. For the first time since the Roman Empire, Syria passes under the control of a Western Power and its destinies are linked with a European political system for the third time in its more than three thousand years of history.

The part that Syria has played in the world’s affairs was the natural consequence of its position on the threshold of Asia. For the European nations that used the sea, it was the gateway to the East, and for Asia it was the outlet towards the West. The stream of commerce and culture that had its sources in China and India, and that for two thousand years flowed westward across the continent, was discharged through Syria into the Mediterranean to be carried along the routes of ancient sea borne trade to European shores. It was the Phoenician, who first controlled that discharge and opened the ports of Asia to the European traffic that came on the returning tide. For if Syria was the spout by which Asia’s stream of wealth was directed to the sea, it was also the funnel by which Europe’s wares, both material and moral, were poured into Asia even to the remotest part of China.

This direct impact of two civilizations, each backed by the resources, and penetrated by the forces of a continent, concentrating and impinging on a narrow space, vitalized the local genius and made Syria peerless in industry and in commerce, while the intellectual and religious gifts that poured from her lap are among the forces that have shaped the course of Western civilization.

Syria still has the same advantage of position as it had in the older world. Its ports, opening on the Mediterranean, still look out towards Europe. Behind them is all Asia with its stores of wealth. Europe still asks for the spices, the fruits, the fabrics, the minerals and the oils of the abundant East and is willing to pay for them. New ambitions are brought to bear on the destinies of Syria and confident spirits do not hesitate to predict a return of its ancient eminence in the new life of a reconstructed world. To the student of history the idea is fantastic, for whatever its role in the future may be, it will be something very different from what it has been in the past. Not in a thousand years, with every ambition and high resolve, could all the mandates projected from Versailles summon the spirit or restore the substance of that ancient splendour of which Baalbek is the shadowy symbol.

Very little is left above ground of the civilization of the Phoenicians except the names of places, which indeed have in some instances survived all the changes of rulers. Such a surviving name is Baalbek which, in the ancient Phoenician tongue, meant the City of Baal. When the Greeks took possession, following the conquests of Alexander in the fourth century B.C., they translated that name into Heliopolis, the City of the Sun, for the Greeks recognized in Baal a solar divinity.

In the summer of 1919 I had the luck to spend five days at Baalbek and the place has haunted me ever since. It is my purpose to try to convey to the reader some idea of what I saw and learned of that abode of the gods.

The gods of the ancient world have a habit of coming back. They are not dead, being immortal; but I am afraid that they are having a very poor time of it just now and that they are suffering from poverty and neglect. I think that the attention of Mr. Hoover or somebody ought to be called to the deplorable condition of these languishing divinities. Some day when I shall have found time to start a society for the care and protection of homeless divinities and old gods in distress, I am going to see to it that all the old Things are accorded their share of decent treatment.

Of these ancient divinities that continue to haunt an ungrateful world, the old god Baal is one of the most persistent. In antiquity he was a very great and a very popular divinity. He was worshipped all the way from Egypt to Babylonia and it was in Phoenicia that he had his favourite habitation. He was so popular wherever he went that the other Semitic gods had to work hard to compete successfully with him. The ancient Hebrews, both rulers and people, were always going over to Baal in spite of the awful denunciations of the priests and prophets of Jehovah, who was represented by them as suffering from violent fits of jealousy. Several changes were rung upon his name as he moved about among different peoples: Baal, Bal, Beel, Bel and Bil are the names by which he was usually known and the Hebrew prophets to whom he was a dangerous rival and therefore the personification of evil, sometimes called him Beelzebub. When, therefore, you appeal to Beelzebub, as I have no doubt you often have occasion to do, you are paying your respects to the old god Baal, Bal, Beel, Bel or Bil.

Image Number: 29294

The Romans were the heirs to both Phoenicia and Greece when they extended their Empire to Syria in 65 B.C. Now Roman political sagacity was not bounded by any provincialism in matters of religion. When they took possession of a country they did not overthrow the altars that they found or drive the native gods into exile. They knew well enough that an exiled god is a dangerous customer and they knew that one of the ways to put themselves right with alien peoples was to make it up to their gods.

When, therefore, the Romans having occupied Syria, took possession of Baalbek, they adopted the Greek form of the name, Heliopolis, and they also adopted the old god Baal. They identified him with Jupiter, who thereupon took unto himself the attributes of Baal and was worshiped at Heliopolis under the name of Jupiter Baal. The scheme was a beneficent one, for Baal became more humane and civilized and Jupiter lost none of his dignity and, having some weaknesses of his own and a rather accommodating disposition, he had not the slightest objection to this identification of his name and worship.

The Romans entered Syria in 65 B.C. and the country today bears striking testimony to their beneficent rule and to their energy during the succeeding centuries. They stretched their roads like white ribbons across the map; they ran their aqueducts over mountain and plain; they flung their arches across rivers and ravines; they dotted the land with walled cities and at Baalbek they stand revealed to us as a race of giants with the powers of Olympian Jove. The site of each one of their cities was selected for a definite reason. Palmyra was built in the desert to control the caravan trade from Mesopotamia, Persia, India and China at the point where it met the caravans coming up from Egypt and Arabia. And Baalbek was built because it commanded the resources of a productive region and because it commanded also the religious traditions of the Syrians.

Syria is divided by two parallel ridges, the Lebanon and the Anti Lebanon running north and south. Between, in the broad and fertile plain, is Baalbek, the Roman Heliopolis, forty miles north of Damascus. Five days’ journey to the east across the desert is Palmyra and down along the fringe of the desert you can trace the lines where the Romans flung their mighty bulwarks round the world to protect it from the inhabitants of the dark outer spaces, represented on this eastern frontier by the wild Arabs of the desert. Behind these eastern bulwarks of their empire the Romans built in Syria a second and a greater Greece and its greatest monument was Baalbek.

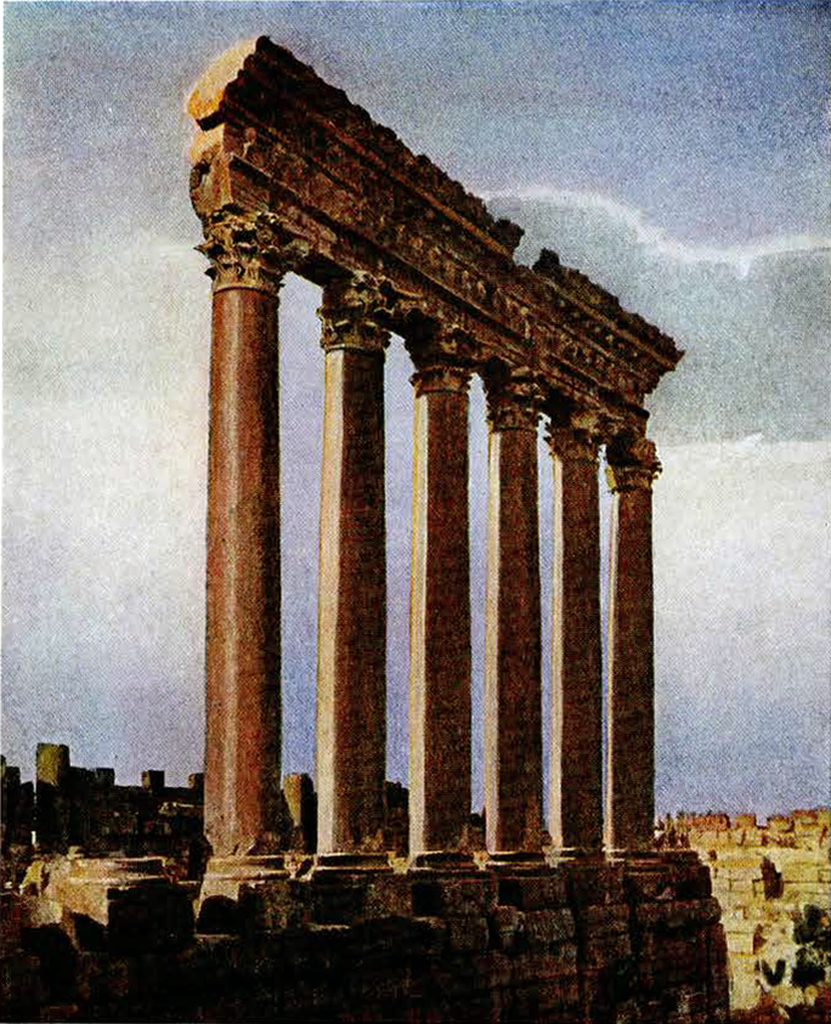

As you approach Baalbek along the plain between the Lebanon and the Anti Lebanon you see in the distance six columns against the horizon rising majestically above their surroundings. As you come nearer you can see below these columns a mass of ruined buildings that take shape gradually as you approach. This is the acropolis and even from a distance the traveler can distinguish clearly two of its main features. The nearer of the two is what we may call for the present the second temple standing against the background of a larger edifice in which the six soaring columns are seen to be raised on a platform. Heliopolis was a walled city and the acropolis stood within the walls in the southwest area. Some of the ancient city walls are still standing and the northern gate is almost intact, but the principal object of interest is the acropolis, now a mass of ruins.

Image Number: 29295

The second temple stood apart, a little to the south, raised on its own platform 15 feet in height. The main temple with its approaches stood on a stone platform raised 26 feet above the ground level. It was 1,100 feet long from east to west and 440 feet wide from south to north. This stone platform did not rest on a solid mass of earth or masonry. It was supported on a series of arched vaults of massive masonry running the length and breadth of the platform and crossing each other at right angles. These vaults are still intact and the platform above them is also unbroken. Besides these vaults there can be seen under the same platform, two large halls with walls and ceilings covered with beautiful and intricate sculpture.

The stairs ascending to the platform were on the east end. They consisted of a triple flight of stairs 160 feet long, nearly all of which have been removed by the Arabs. At the top of this flight rose the great gateway, portico or propylon, a word that I will use because it means a monumental entrance. This propylon was 160 feet wide and 36 feet deep. On right and left it was flanked by two massive towers and adorned in front by a row of twelve columns supporting the entablature. The back wall of the portico still shows twelve niches for statues of heroic size and was pierced by three doorways, the largest in the center being 26 feet high and 18 feet wide. The sockets without their bronze castings in which the great double doors swung are visible in the stone sills. In the thickness of the wall between these doors were two winding staircases leading to the roof, now fallen. The entire propylon, though permitting of measurement, is reduced to a mass of ruins.

The three doors led to a hexagonal court with a sunken basin in the middle surrounded by a row of Corinthian columns. On four sides of the hexagon were four great chambers with open facades adorned with Corinthian columns and six smaller rooms of irregular shape entered by small doors. The walls of the four large halls, still standing, had two rows of niches for statues, one row above the other. This hexagonal court was roofed over from the inner row of columns to the outer walls, the sunken area in the center being left open to the sky, so that you could walk around from the outer entrance to the inner entrance without being exposed to the weather. The traveler today looking westward from the court may envisage in one view the ruins of the great temple and its monumental approaches. In the distance, at a higher level, is the wreck of the temple itself with the six remaining columns rising above the snowcapped Lebanon mountains and etched upon the sky. This hexagonal court was 260 feet across and a triple doorway on the west side led to the square court which measures 440 feet from east to west and 385 feet from south to north. In this square court also was a sunken central area open to the sky. Around the margins of this open area stood once a row of Corinthian columns 25 feet high supporting a marvelous sculptured entablature nine feet high on which the roof rested. Behind these columns a wide covered passage ran around three sides of the court. Adjoining this colonnade and opening from it, a series of halls, some oblong and some semicircular with open facades adorned with Corinthian columns supporting another sculptured entablature, ran around the three sides of the court. In the open court itself are still to be seen two basins for running water, each basin being 68 feet long, 23 feet wide and 3 feet high, richly sculptured on the outside. Midway between these two basins stood the great altar 34 feet square.

This great courtyard is a jumble of ruins. Not one of the columns is standing and the whole space is strewn with fragments of noble structure that once formed part of cornice, capital, architrave and molding. In the walls of the chambers around the sides of the square court and the hexagonal court there can still be seen and counted 350 niches for statues. There is one more remarkable fact to be mentioned in connection with these two courts. All of the columns that adorned both of these courts and that adorned the propylon, about 200 columns in all, were monolithic shafts of red granite 25 feet high and 3 feet in diameter That rose colored granite is not found anywhere in Syria. It is found only at Aswan in Egypt, 700 miles up the Nile. All of these granite shafts therefore were quarried at Aswan, floated down the Nile, rafted across the Mediterranean Sea and hauled over the Lebanon Mountains to be set up at Baalbek.

Image Number: 29296

Now all that I have been describing is only the introduction, the approach, the vestibule of the principal edifice, and that edifice that roars so loud and thunders in the index was once the temple of Jupiter Baal and a wonder of the ancient world. It rose on a second platform 26 feet higher than the first or 52 feet above the ground level. It was 175 feet wide and 310 feet long and was reached by a flight of steps running the entire width of the building, 175 feet. A man standing at the great altar and looking up at the temple would see its broad façade towering 150 feet above his head. In plan the temple consisted of a cella surrounded by 54 Corinthian columns forming the peristyle and 8 forming the portico, 62 columns in all. Only 6 of these columns remain standing, the columns that loomed on our horizon as we crossed the plain. The whole structure was roofed over and the apex of the roof rose high above the tops of the columns, forming a triangular pediment in front. Within the west end of the cella was the sanctuary, and there must have stood the statue of the god, and as this would be of a size proportionate to the building it must have been of colossal dimensions. Of the massive walls of the cella itself not a single stone remains upon another.

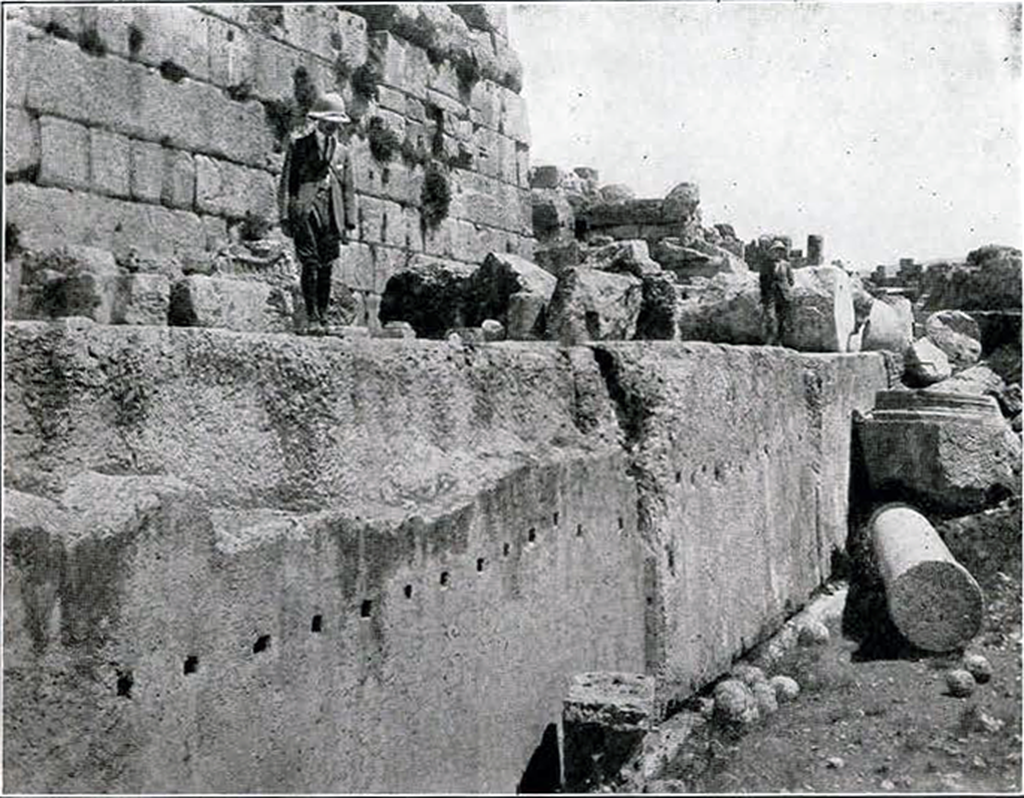

I come now to an amazing feature that has taxed the credulity of generations of men ever since Baalbek was rediscovered in the sixteenth century. Around the three exposed sides of the temple, below the bases of the columns and at a distance of 25 feet from the wall of the platform on which it was built, there is to be seen today an unfinished rampart which remains exactly as it was left by the masons, the space between the rampart and the platform wall being filled in with solid masonry. I will only call attention now to the fact that the upper course of stones on the west side of the rampart consists of three stones, not counting the ends of the side courses, and that the total length of that west section of the rampart is 225 feet. Each of the two side courses, one on the north and one on the south, contains nine stones and the length of each course is 335 feet.

Before proceeding with the description of the temple of Jupiter Baal it will be necessary to get some idea of the style and proportions of the second temple, which is much better preserved. The second temple, if it stood by itself, would be remarkable for its size and magnificence, but it is dwarfed by the immensity of its huge companion. Its entire structure is of fine white marble to which time has imparted a rich brown tone. Part of the peristyle is standing and the walls of the cella are wonderfully preserved. The columns of the peristyle are made in five sections each, they are 60 feet high and 5 feet in diameter; they support a fine entablature and the distance between the columns and the walls of the cella is 10 feet, and that space of 10 feet is bridged above by great blocks of stone reaching across the architrave to the wall and forming a vaulted ceiling exquisitely carved. In hexagonal spaces placed at intervals on this ceiling are portraits of all the gods and of their numerous progeny and with their emblems, reaching all around the building and looking down upon us from the ceiling, the carved decoration of which is altogether exquisite and wonderful.

Passing opposite the portico which, with the exception of the two columns of the southern end has fallen way, you find this portico consisted of eight fluted columns, the only free standing fluted columns at Baalbek. Here also you can see the upper part of the flight of steps that led up to the portico, over which steps the Arabs have built a castle.

Image Number: 29297

The entrance to this second temple is 43 feet high and 23 feet wide and is surrounded by a border of beautiful sculpture. On the soffit of the lintel is carved a great eagle with wings outspread. The lintel is made of three stones, and many years ago the keystone in the center had become loosened and had slid down until it seemed to hang as by a hair. Sir Richard Burton, when he was Consul General at Damascus, built up a pillar of small stones to take the weight of the great keystone and support it. It weighs many tons. In the thickness of the wall, at the right of the door as you enter, is a winding stair cut out of the great blocks of stone. Passing within the temple you find that the roof is entirely gone and that the interior walls, presenting engaged fluted columns of the Corinthian order, are fairly well preserved.

This is the time to relate an incident in the recent fortunes of Baalbek which may serve both as a footnote to history and as a typical modern instance. In 1898 when the German Emperor made his tour of the East he visited the ruins, together with the Empress and the Sultan of Turkey. The Kaiser then obtained permission from the Sultan to send a German archaeological expedition to make excavations at Baalbek. The mission, consisting of twelve men, arrived in 1901 and they employed about four hundred natives making excavations for four years. My main purpose in referring to this episode is to call attention to two things that the German archaeologists did, one good deed and another. They found the great keystone in the lintel of the doorway propped up as Sir Richard Burton had left it. They raised the keystone again into its original position and fastened it in place by means of a heavy iron strap sunk in the stone. They were then able to remove Burton’s pillar without the risk of dropping the keystone and to continue their excavations about the entrance. That was what may be called their good deed. In one of the niches in the interior wall of the temple there was to be seen before the war a new tablet of white marble. That tablet contained an inscription in German and in Arabic. The German inscription was in very elaborate Gothic letters cut in the white marble and filled in with gilt. Above was the Emperor’s coat of arms; then came the name of the Emperor; then that of the Empress; then the name of the Sultan of Turkey and last but not least, the name of God. Then followed a long inscription highly complimentary to all four and giving the date at which that distinguished company visited Baalbek.

When my time came to visit Baalbek that tablet was no longer in its place on the wall of the temple. It was lying with a lot of other rubbish on the floor of the Arab castle near by. This is what happened. When Lord Allenby after his victory over the Turks and their German Allies was marching northward he passed Baalbek and placed an Australian garrison there, and it seems that these astonished troopers from the sheep ranges of. Queensland and the streets of Brisbane, whose reputation is not exactly that of artists and whose constitutions were proof against most forms of atrocity, were nevertheless moved to take down that tablet from its place and assign it to a more appropriate setting on the rubbish heap, and I feel quite sure that when the Australians next went into battle, all the inhabitants of Olympus gave them every assistance in their power.

Before leaving this second temple I want particularly to put it on record that after a long controversy among scholars as to which of the gods this temple belonged to, the question has been settled to the satisfaction of everybody, and I rejoice to be able to record the decision that this beautiful temple, so noble in proportions and so exquisite in detail, was dedicated to no other than our good old friend Bacchus of the wine cups.

Image Number: 29298

The temple of Bacchus is, as I have said, very much better preserved than the temple of Jupiter Baal, for the latter has been used as a quarry since the fall of the old religion at the end of the fourth century. Churches, mosques, castles and fortresses have been built from it and the crowning feature of that chaos of ruins consists in the six standing columns supporting a fragment of the entablature.

These columns are 66 feet high. The bases are 8 feet high and the capitals are 8 feet high. The shaft of each column is built in three sections and each shaft has a minimum diameter of 7½ feet. The columns support an entablature 15 feet high. This entablature consists of three horizontal members; the architrave resting on the capitals, the frieze resting on the architrave and the cornice resting on the frieze and completing the entablature above. Each of these horizontal members consists of a single course of stone and each stone is 17 feet long and 5 feet high and weighs not less than 30 tons. Bases, shafts, capitals and entablature are all of white marble now turned to a rich warm brown and gold. Part of the wall of the platform on which the temple stood is exposed below the bases of the columns and the big stones forming the wall of the unfinished rampart that enclosed the temple platform on the three exposed sides can be seen below.

Fallen capitals and fragments of architrave, frieze and cornice are lying about in heaps. From these one can examine in detail the sculpture that was carried around the four sides of the temple. Lions’ heads at intervals on the cornice served as gargoyles to carry off the rain water from the roof.

I come now to the rampart wall that was carried around the northern, western and southern sides of the temple platform at a distance of 25 feet from the latter. That rampart was never finished.

The course of stones in the southern range was intended to carry another course of the same dimensions and that was to carry a third course forming a huge ornamental cornice giving a finish to the top of the wall. Each of the stones in position is 15 feet high, 15 feet wide and 44 feet long and there are nine of them in this course. Two more courses of these stones would bring the top of the rampart wall up to the level of the platform wall and to the bases of the columns. The space between was to have been filled up with solid masonry to form a terrace running around the three sides of the temple and commanding a magnificent view on all sides.

On the western side of the rampart wall which is the end wall, the second course of big stones was already put in place. This course of stones is 195 feet long and it consists of three stones. Each of these stones is 15 feet high, 15 feet wide and 65 feet long. One more course of these stones would bring the wall up exactly to the level of the columns of the peristyle and on a level with the platform wall, which is 25 feet inside. Of special significance is the fact that the faces of these huge stones are not finished.

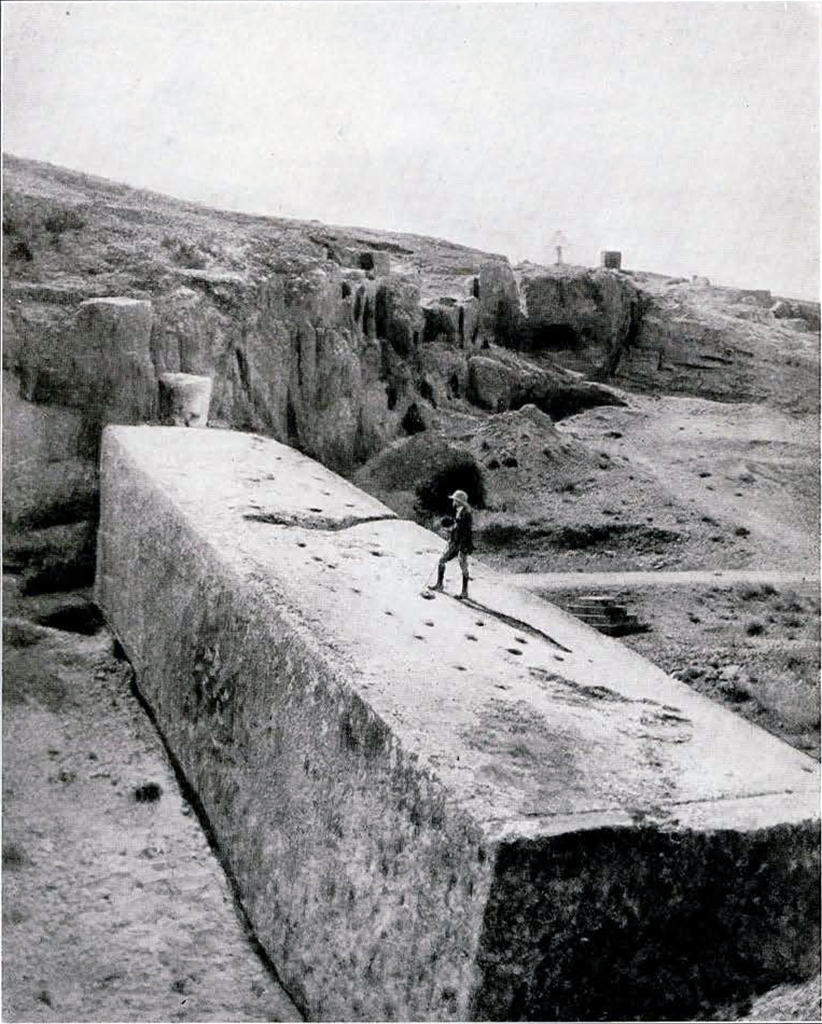

Let us go to the marble quarry three quarters of a mile away and see what we shall see. At the entrance to the quarry we find a stone, a block of marble of uniform quality and without flaw, 16 feet high, 16 feet wide and 69 feet long, and it weighs 1500 tons; but there are more and greater wonders to come.

I have not yet mentioned the joints between the big stones that were put in position in the rampart wall. These joints to my mind are even more remarkable than the stones themselves. To illustrate what I mean I here present a photograph taken where two of the stones in the southern range come together. This course of stones was being cut away at the top so as to form a battered surface and on the stone at the right the batter was not finished. But I want to call attention to the joint between the two stones which may serve as an example of all the joints that were made in the rampart walls. What you see is a vertical V-shaped groove with polished sides at the place where the two stones are joined together and the joint, which is at the bottom of the V-shaped groove, is so fine that it is invisible and can be detected only with a strong magnifying glass. This close contact of the two stones extends from front to back and from top to bottom. I am using no exaggeration when I say that it is like the invisible joint in a polished mahogany table top. It is scarcely necessary for me to add that no mortar or filling of any kind was used in the masonry construction at Baalbek.

Four questions now present themselves as follows.

First. Who built the temples of Jupiter and Bacchus, and when?

Second. Why did they use such huge stones, the largest that have ever been used in construction?

Third. How did they move these stones?

Fourth. How and when were the temples destroyed?

Let me say at once that only the last of these questions admits of a definite answer. The answers to the others, if they are forthcoming at all, must be based on conjecture.

The first question, Who built the temple, and when? is answered by the inhabitants of the country in the following interesting way. They say it was built before the Flood by the giants who lived in those days; they affirm that no race of men since the Flood were big enough or powerful enough to accomplish such a task. They contend that since the Flood men do not live long enough to do so much work, and it must be admitted that there is something in that. In an interesting historical work written by the Grand Patriarch of the Maronites, the Christians who live in the Lebanon, there occurs this interesting and illuminating passage:

“Tradition states that Baalbek is the most ancient building in the world. Cain, the son of Adam, built it in the year 133 of the Creation in a fit of raving madness and with the help of the giants who were punished for their iniquities by the Flood.”

Such is the testimony of local scholarship. Our wiser Western scholarship is much less explicit and direct and much less final in its conclusions. We are to believe that there is not a stone visible at Baalbek that is older than the Roman Empire. That much may be positively asserted. Not a trace has been found of the original temple of Baal that must have stood on the same site. Whatever it was like it has entirely disappeared and was replaced by the temple whose ruins have excited astonishment and incredulity since they were made known to the world by a European traveler in the middle of the sixteenth century. It seems strange that such a place should have been forgotten for a thousand years, but it is still more strange that the Roman historians make no mention of the building of that wonderful temple.

The names of four of the Emperors have been associated with the Temple of Jupiter Baal. We are told that Trajan towards the end of the first century, while on a campaign in the East, visited Heliopolis and consulted the Oracle. There must therefore have been a temple in Trojan’s time, but it is not known that it could have been the same that I have been trying to describe. The name of Antoninus Pius, who reigned fifty years later than Trajan, has been connected with the foundation of the Temple. That connection is based on a statement found in a history written in the seventh century, 500 years after the time of Antoninus Pius, who reigned from 138 to 161, a span of 23 years. There are two difficulties about accepting the statement that Antoninus built the Temple. It is hardly credible that a work of such magnitude was accomplished in the space of 23 years, and moreover the personal friend and biographer of Antoninus makes no mention of any such act on the part of his Imperial patron. The name of Septimius Severus who reigned at the end of the second century, has also been connected with the building of the Temple. This connection is based on the fact that there are some coins of Septimius that show the outline of a temple with the words Jupiter and Heliopolis. These coins have furnished ground for the idea that it was Septimius Severus who, during his reign, dedicated the temple of Jupiter to Baal, but the historian Dion Cassius, the friend and biographer of Septimius, makes no mention of the subject at all. The name of Caracalla, his son and successor, has also been connected by some writers with the finishing of the Temple, but that idea again is based on some coins of Caracalla.

Image Number: 204511

The inscriptions found at the ruins do not help us, for there is not a single inscription that gives the name of the builder or that refers at all to the construction of the Temple. The fact remains that we do not know the date or the name of the builder. The style is that of the Roman Imperial Age and that is all we know of the origin of the greatest work that man has ever had the audacity to plan or the energy and skill to execute.

As to the second question, Why did they use such large stones? and why did they join these stones together with such incredible and unusual precision? The motives that men have for doing anything reduce themselves to a very few. The proximity of Egypt where the Romans had by this time grown accustomed to seeing in the work of their predecessors, the ancient Egyptians, massive masonry, huge blocks of stone and exceeding fine joints might have suggested to them a plan for surpassing the Egyptians in their own distinctive arts; but if that had been their chief incentive they would have chosen to beat the Egyptians on their own ground and would have achieved their triumph in Egypt rather than in Syria.

It was not for defense that they raised these stones, because the city wall enclosed the Acropolis and for defensive purposes they would have put the biggest stones in the city wall. When I saw that the surface of these huge monoliths remained unfinished it occurred to me that the builders had planned to cover the surface of the entire walls of the rampart with sculpture in relief, perhaps with scenes from mythology representing the inhabitants of Olympus or some similar scheme familiar enough in Greek and Roman art and architecture. It is obvious that for such a purpose the bigger each unit of construction the better, and it is also obvious that the finer the joints where they intersected the work of the sculptor, the better for his work and for the appearance of the finished surface.

Now for the third question. How did they move these stones and lift them into position, and how did they make such joints as those that we have seen? You already know the explanation of the native and I think there are reasons for dismissing the theory of giants before the Flood. The question is usually dismissed with the statement that the builders had legions of slaves whose normal energies and resources were, it seems, developed to an astonishing degree by the liberal application of portentous and magic whips, and whose unskilled labor miraculously transformed itself under the same treatment into the most refined and exquisite craftsmanship. That is an interesting theory, but there are objections to the theory of slaves and I find myself unable to entertain it. In the first place it has no historical basis at all. In the second place, Baalbek did not impress me as the work of slaves. It impressed me rather as the work of men who loved their toil and who gloried in the labor of their hands. It impressed me as the work of men who handled their tools with affection and who caressed the marble as they wrought it till it yielded to their touch and responded to their will for the sake of the love that they bore it. In other words, it all impressed me as the work of men who are as extinct today as the giants before the Flood.

What mechanical devices were used I do not know, but I think it will be agreed that the magicians who juggled with these stones, tossed them about, chucked them up on the top of walls and balanced them on the tops of columns and never thought of mentioning it at all, have furnished us with an interesting standard by which to measure our own performance. But when, in addition to that, they ranged those stones up together with the precision of science and with a cabinetmaker’s joints, I confess that I find it a little bit provoking on their part, for it looks as if they were rubbing it in on us.

Now for the fourth and last question. How and when were the temples destroyed? We know that the Emperor Constantine after his conversion to Christianity ordered the temples of Baalbek to be closed some time during the first half of the fourth century, and at that time the great gates were shut on the worshipers of Jupiter and Bacchus to remain closed throughout the succeeding reign. Then to the Imperial throne at Constantinople came Julian, whose reasoned conviction that the preservation of human civilization and Greek culture required the restoration of the old worship was given public effect by his avowal of paganism coupled with toleration for all creeds. The temples of Baalbek were opened once more for public worship, but the respite was short, for two years after coming to the throne Julian was killed on a Persian battlefield (363) and with him died the last hope of paganism; but it remained for Theodosius, who reigned at the end of the fourth century, to celebrate the victory of Christianity by an edict ordering the destruction of the pagan temples throughout the world. The overthrow of Baalbek, then begun, was carried on for centuries by the Christians and by their successors, the Mohammedans. Already in the time of Theodosius a church was built in the great court of the Temple of Jupiter with stones wrenched from its mountainous walls. Statues were burned to make lime or wantonly destroyed, and even the portrait busts of the gods carved on the ceiling of the peristyle of the Temple of Bacchus 65 feet in the clear overhead were systematically and laboriously defaced, as may be seen today where the great stones of that ceiling are still in place, but it was the Temple of Jupiter Baal that suffered most. Besides the Church of Theodosius many other Christian buildings were raised from its well hewn stones during the two and a quarter centuries through which the Christians remained in possession. When at last the Arabs broke through the Eastern defenses and drove the Romans out of Syria in the seventh century, they completed the destruction to convert the great platform of the Acropolis into a fortress and, throughout the succeeding centuries, to build mosques, castles and palaces from the temple masonry. Meantime to the outside world Baalbek was utterly forgotten for a thousand years till a European traveler at the middle of the sixteenth century made the ruins known to Europe and when Wood and Dawkins, two English architects, sixty years later published their drawings, they were able to convince the world that the story was not a myth.

I am not bold enough to attempt to decribe the emotions of a pilgrim in the presence of this ruined shrine. The effect conveyed by the eye to the astonished mind is matched in a wonderful way by the sensations of the ear, for the breeze that is always blowing strikes from these uplifted stones a clear melodious sound, sustained on a single chord and pitched in a minor key and when the gale sweeps down from the Lebanon these tall columns of sounding marble vibrate like the strings of an AEolian harp, flinging on the winds their soft lament.

On the south front of the standing columns the state of preservation is good, but the winds and the storms come from the north so that the northern exposure faces the weather and on that northern exposure where the rains, the snows and the hail drive against the unyielding stone and where the fingers of AEolus have swept the strings of this Olympian lyre, it shows worn and battered like some tall cliff that fronts a stormy sea.

While we are looking at this picture let us not miss its full message, lest what we have seen should make us feel too proud of Adam’s breed. If this picture shows us on the one hand man, the architect, in action like a god, it also shows him up in action like an insect or a worm. When the builders raised these columns they placed bronze dowels sunk in lead between the base and the foot of each column and some one in the course of time has cut away the stone at the foot of every column to extract the lead and bronze; and yet with only half a foot to stand on, each column continues to bear up its load and has weathered every storm and every earthquake. So long as these six columns stand as they stand today, serene above the warring nations—these valiant sentinels that have braved, age after age, the hostile elements and the violence and rapacity of man—so long will men bear witness that here a miracle was wrought in stone.

Now imagine nineteen of these columns in a row with the entablature spread above them and restore in your mind’s eye the wall of the cella behind them, spread the roof over it all and raise the rampart of the big stones to the level of the bases of the columns to form a terrace and finish the rampart above with a gigantic sculptured cornice and imagine the face of the rampart wall around the three sides of the temple to be carved in figures of heroic size representing scences on Olympus, and you will see in your mind’s eye a fraction of the vision of the architect who planned the Temple of Jupiter Baal.

When the sun rises above the Anti Lebanon and the splendour falls across the wreck of eighteen centuries you may conjure up, though dimly, some fragment of that vision; and if you are worthy, power may be given you to read between the lines of the dissolving marble some syllable of that builder’s thought.

I remember a morning when I stood below the six majestic columns and watched the dawn come up. High up in the air, where the uplifted stones poured out their heart upon the breeze, in that soft booming sound that floated down the centuries, I fancied that I heard in that mystic chord the voice of the old divinity, the plaint of the great god Baal. It seemed to fill the firmament and pervade the vault above, and I should not have been at all surprised if I had heard Apollo’s bowstring twang or seen Jove’s thunderbolt descend.

But where I stood below, the ground was warm with human heart beats, for in that enchanted atmosphere I felt the stirring of men’s thoughts and I felt the pressure of the faith of men. There was a mighty presence that enfolded me, and, wrapped about me like a vapor, the immortal spirit of a master mind. And as I looked upon his ruined workmanship, the tumbled columns and the stolen stones rose up and took their appointed places and the void was filled once more with the vision as the builder saw it in the realization of his dream. But I had no standard to take the measure of the mind that worked that miracle and I had no instrument to gauge or arithmetic to estimate the thought that found its habitation in that mind. Yet as I traced the lines of his foundations and his plan unfolded itself acre upon acre around me, a plan that was so nearly finished and now so utterly undone, I felt that it was not so very far along the road that I was traveling to the heart of that builder’s heart.

You cannot have failed to notice that wherever a bad building defaces the landscape, nature refuses to be reconciled to its presence, and that wherever there is a beautiful or a noble work of human hands, whether it be a cottage or a palace or a temple, nature seems to appropriate that object and in caressing accents to call it her own. How well this partiality of nature is brought home to us at Baalbek even the photographs confess; for the voice of nature seems to be saying: This temple is my very own, it is planned after my own fashion, it rhymes with my rivers and my waterfalls, it is made like my mountains, it is one with my thundercloud.