I

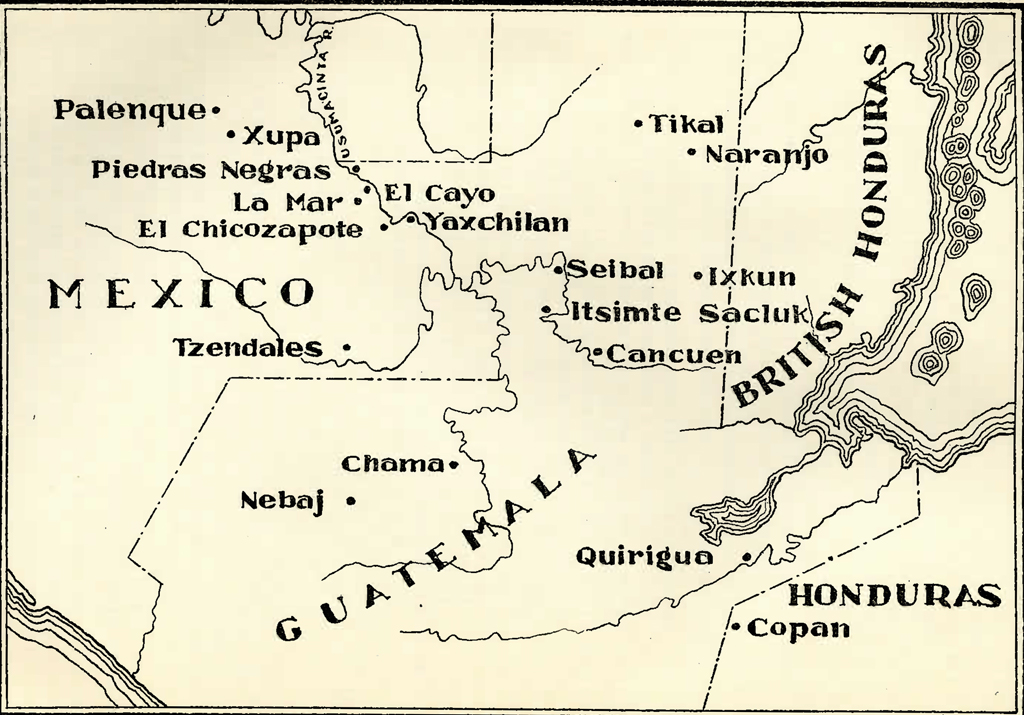

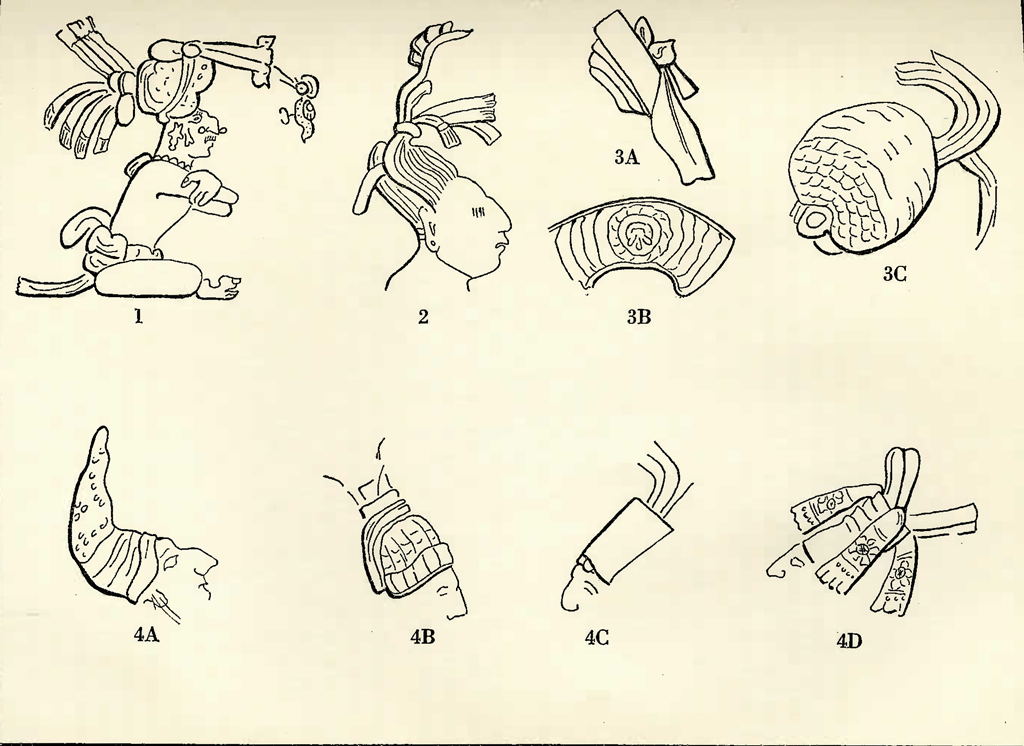

ALTHOUGH the monuments of the Maya Old Empire — monolithic stelae and altars, stone and wooden lintels—are few in number and often badly worn, they are the fullest record we have of the dress of the people who raised them, for we have too little data on the provenance of most carved jade plaques, painted pottery, and terra cotta figurines to use them as primary evidence. The monuments show us the elements of costume found everywhere so combined in different cities as to give each site a distinct individuality. The irreducible minimum of Maya garb was headdress, neck ornament and girdle or loin cloth [Figure 1]. These, in one form or other, are universal; additional capes, skirts, sandals, leg and arm bands appear sporadically.

HEADDRESS. The early Maya seem, like their later brothers, to have worn their hair long. Monuments from every southern site show figures, who, lacking more formal headdress, have their hair pulled up to the crown of the head, bound by ribbons or strips of cloth, and then allowed to hang or float at will, an inexpensive substitute for the feathers used on all forms of headgear [Figure 2]. Sometimes beads were strung separately or in groups along these locks of hair, sometimes feathers or flowers were mingled in the culminating tuft or in the binding, sometimes snake skin was used for binding or a bandeau. Some of the headdresses at Palenque and Yaxchilan are elaborations of this treatment, while others show the hair tied at the back of the neck. Almost every figure, however, on reliefs, jades or pottery, boasts a more or less elaborate example of one of the two main forms of headgear — turbans and mask headdresses.

Textile turbans take three forms: the horizontally folded, the vertically folded, and the round. The first, found at Copan, is the shape of a truncated, inverted cone [Figure 3, a]. On its base, the top of the turban, may stand another truncated zone, a bird, a crocodile, or formal loops and knots. It is also used on stela B as foundation for a mask headdress, and on stela I has only a very thick base to top it off.

The second form is found at Piedras Negras, sometimes with a snake mask on the front, or as a base [Figure 3, b]. The turban on stela 14 is decked with a death’s head, and that on stela 1 with planetary symbols bounded by frets.

The round turban occurs at Tikal, Copan, Piedras Negras and on the Chamá pottery [Figure 3, c]. At Copan, it is hidden under a flame-like scroll, or appears as a neat hemisphere trimmed with three bows at the sides, and small grotesque heads at the back and front. Stela 35 at Piedras Negras may show a round turban as the chief element in the headdress; on stela 9 such a turban serves as foundation for planetary signs and base for an owl’s head; on lintel 4, it bulges, unadorned, above a possible owl’s head, and, large and balloon-like, is the only one that resembles the turbans on the pottery in its apparent roughly woven surface. The latter are trimmed by an occasional textile knot, a flower with feeding bird, or a flower and fish.

Various forms of cap are also found: a definitely pointed textile one at Yaxchilan [Figure 4, a], and tall cylindrical ones at Piedras Negras. That on stela 12 is topped by what may be an embryo turban, that on lintel 2 by an entire macaw. The helmets of the row of soldiers on this lintel are probably quilted caps [Figure 4, b]. At El Chicozapote, a tall cylinder tufted with feathers rests on top of the head [Figure 4, c], and the priest on the Palenque sanctuary tablets has a wide band wrapped or tied about his head into the same shape, while the worshipper wears a cap with four flaps falling from the top [Figure 4, d].

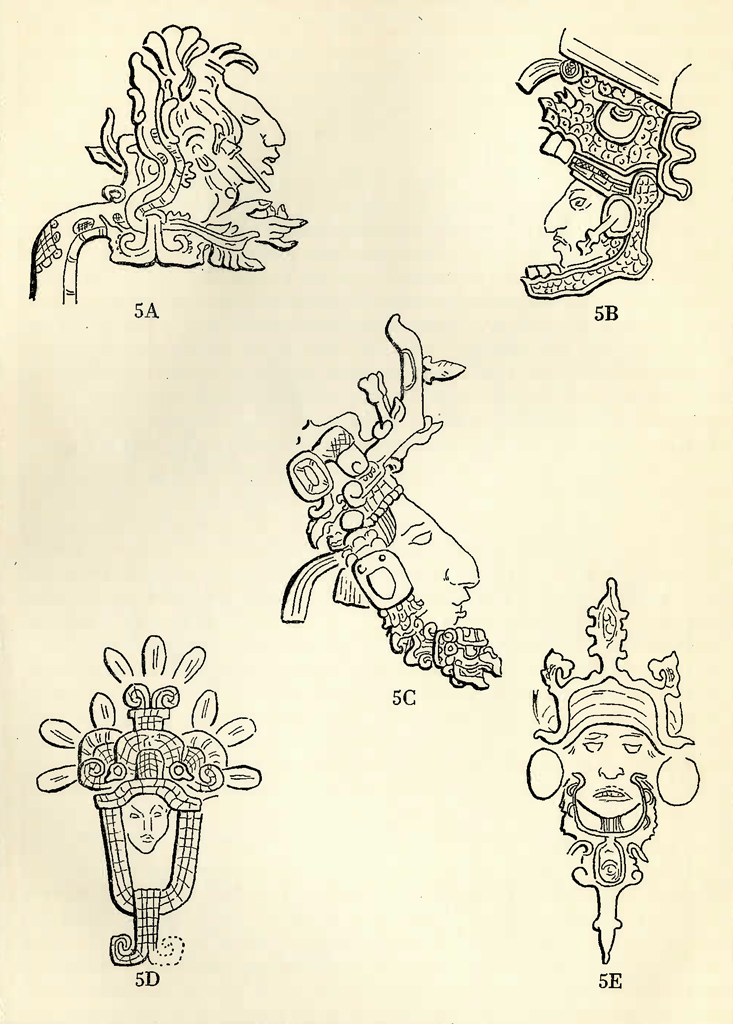

Mask headdresses probably derive from those which show the wearer’s face framed in the jaws of a snake, thus imitating the deities, who, on monuments and codices, project whole or in sections from the mouths of serpents or mythical monsters [Figure 5, a]. An apparent sequence in this type of headdress can be traced in the dated monuments that show it. A lintel from Temple III at Tikal, dated A. D. 228 according to the Spinden-Morley correlation, used in this paper, shows the wearer’s face between complete upper and lower jaws [Figure 5, b]. On stelae P, 2 and I at Copan, dated A. D. 363, 388, 407 respectively, and the undated stelae 1 and 2 at Tikal and the figure on the west side of the doorway in the Temple of the Cross at Palenque, the lower jaw has become a chin strap with a grotesque mask in the centre [Figure 5, c]; the latest of those dated, however, is the most realistic. At Piedras Negras, stelae 26, 31 and 7, dated A. D. 368, 378, 405, respectively, show another line of development of the lower jaw highly conventionalized [Figure 5, d], of which the beardlike appendage on the faces on stelae B and F at Copan, dated A. D. 471 and 523, may be a degeneration [Figure 5, e]. A chain hanging to the breast, at Tikal, and two chains terminating in serpents’ heads at Copan and Quirigua may be survivals of this idea, though this last ornament is found as a chain hung over the tree on a Palenque tablet. Headdresses, showing the front view of the upper jaw of a reptile snout, but lacking the lower jaw, appear at Copan and Piedras Negras, and on jade plaques [Figure 5, d]; such a snake snout is shown on a shield at Cankuen. These may be the same headdress that is shown in profile at Naranjo, Copan, Yaxchilan, Quirigua, Palenque, Tikal and Ixkun: various masks, lacking the lower jaw, of God K or his serpent proto-type [Figure 5, c]. Animal masks, as well, sometimes crocodile, sometimes jaguar, are often the main element in a headdress, and even a death’s head is occasionally used. A variation is the headgear in which, over hair or head covering, is fastened, at the angle of a visor, a band decorated in front with a grotesque or reptilian head [Figure 6, a].

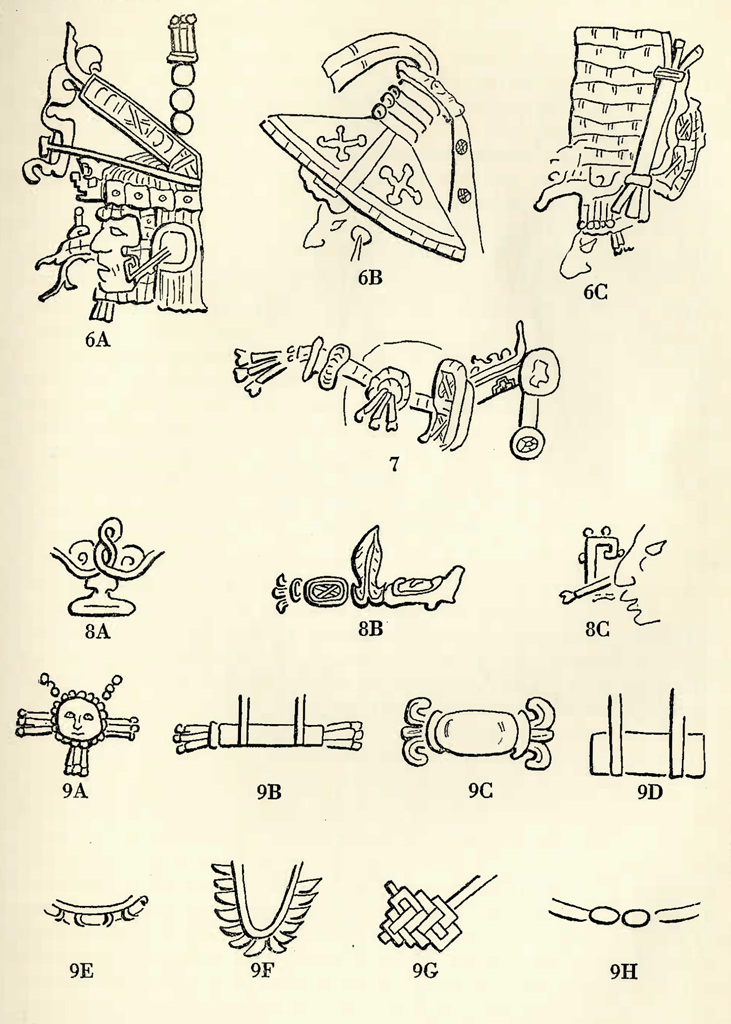

There are, of course, headdresses that do not fall into these two main classifications, such as a broad-brimmed hat, seen at Tikal, that is much the shape of the straw ones worn by the Indians of the Northwest coast, and is decorated with the crossed bones found at Piedras Negras, Chichen Itza, and on the cloak of the Bat God on a Guatemala vase [Figure 6, b]. A headdress of a crown of feathers surmounted by a large bird’s head is worn by God D at Palenque, and by God N on a vase in the University Museum. Then there are headdresses at Copan, Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan that are difficult to classify except as braided or woven structures; several of these at Yaxchilan are characterized by stretches of striped or folded textile that may be derived from the turban [Figure 6, c]. Here, also, and at Cankuen and Piedras Negras, the serpent’s tail, curled, is used as a base for construction [Figure 27].

For almost all these headdresses have a great deal of additional ornament; none, for instance, is without features at top, sides or back; some, in fact, are composed of little else. The snake, or some portion of his anatomy is the most prevalent decorative element: used entire at Copan, Piedras Negras and Seibal; half emerged from the top of the headgear at Yaxchilan, Naranjo and Palenque; one or more tails at Piedras Negras, Yaxchilan and Cankuen; an upper jaw at Copan; and a miniature sort of Ceremonial Bar at Piedras Negras. Additional heads or masks, human, grotesque, animal or reptile, are found in some form or size on headdresses at every site except Naranjo. Three superimposed round beads beneath an inverted bell-shaped one [Figure 6, a], usually serving as base for a burst of feathers, appear on top of headdresses at Tikal, Quirigua, Piedras Negras, Yaxchilan, Naranjo and Seibal. At Yaxchilan long neckbeads and an abbreviated openwork spear are sewn vertically at the sides [Figure 6, c]. A stela at Piedras Negras and a lintel from Tikal have textile rosettes in front and a sort of hinged elbow projecting from the rear [Figure 7]. Signs and symbols are fairly frequent; probable planetary ones at Copan, Tikal, Quirigua, Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, Palenque; a hand, palm out, at Copan, Piedras Negras, Seibal, Palenque; a fish feeding from a flower at Copan, Ixkun, Palenque, on pottery from Chajcar and Nebaj, and in borders at Palenque and the Chichen Itza ball court ; a flower at Yaxchilan and Palenque; a fish at Piedras Negras; a bird feeding from a flower on a Chamá vase; a heron with a fish in its bill at Palenque and Seibal; a bird at Piedras Negras, Seibal and Copan. What Spinden refers to as a cruller-shaped symbol probably belonging to the sun god [Figure 8, a] is found over the nose of figures at Tikal, Seibal, Naranjo; on the head on the girdle of a Copan stela; and on that of shields carried at Tikal, Ixkun, Naranjo, Itsimte Sacluk and on the Gann jade plaque; and what he calls the symbol of the back, underworld head of the Two-Headed Dragon [Figure 8, b] occurs at Copan, Piedras Negras, Yaxchilan, Palenque; at the last-named site on an object held, as well as on a headdress. A fret curling up from the nose of a figure, in two instances at Yaxchilan [Figure 8, c], is exactly like that on the Gann plaque, proving that the latter is not a degenerate Toltec speech scroll but a purely Mayan symbol.

NECKLACES. These were practically universal, long and short, usually of round beads, but sometimes, as at Copan, of round and cylindrical beads combined. These beads were probably jadeite, as most of the stone beads found so far have been made of this material. Some of these necklaces at Copan, Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras and Palenque have down the wearer’s back an additional string ending in a tassel [Figures 1 and 26]. An amulet of a human face edged with small round beads [Figure 9, a] appears in the front of such strings of beads at Copan, Quirigua, Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, Tsendales, Palenque, and even at Chichen Itza in the New Empire; usually three pendants, each of a long and a round bead, hang from the amulet, and three project from each side. At Piedras Negras a personage wears an amulet of an entire human figure. A long tubular bead, with similar rays at each end, suspended from thongs or textile strips [Figure 9, b], was worn at Copan, Quirigua, Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, Seibal, and is seen on jades and on the pottery; a possible development from it, or else degenerate conventionalization of the Ceremonial Bar (see Copan, stela 11; Quirigua, stela C) is a flat, oval bar, with trefoil projections at the ends [Figure 9, c], found at Tikal, Quirigua, Piedras Negras, Yaxchilan and Naranjo. An oblong bar, similarly suspended [Figure 9, dl, is found at Copan, Tikal, Naranjo, Cankuen, on stone figures from Copan in the Peabody Museum, and on the Chamá pottery; and an apparently inflexible carved necklace, associated by Seler with the Death God, appears at Copan, Quirigua, Naranjo, Seibal, and on the Bat God of the Guatemala pottery [Figure 9, e]; here the girdle is similar. A necklace of leaves on a narrow band is worn short at Piedras Negras and long at Naranjo [Figure 9, f]; at Palenque and Tikal an ornament of woven ribbons or textile strips hangs at the level of the wearer’s waist [Figure 9, g] ; at Palenque, an elaboration of the long bead hangs from a knee-length intricately carved chain; at Yaxchilan, on the pottery, and on a jade piece as well as on a painted vase two large oval objects, probably beads, are held tight at the neck by a thong [Figure 9, h].

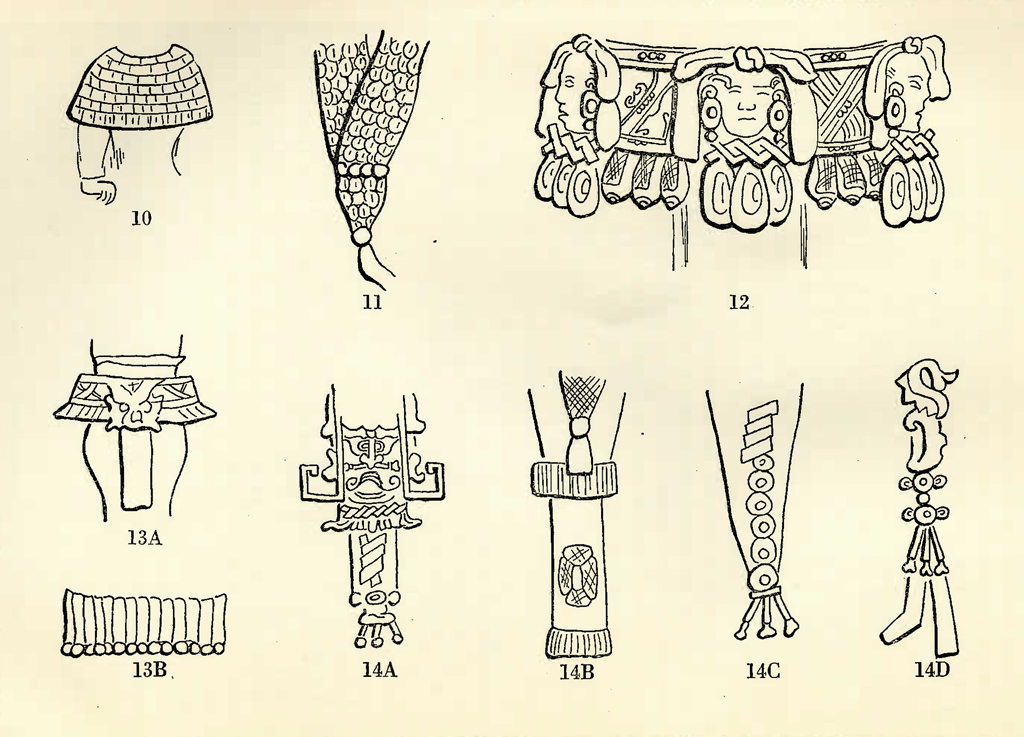

Circular collars [Figure 10], sometimes long enough to be called capes, made sometimes of round beads, sometimes of round and cylindrical combined, but usually of close set squares that are perhaps jadeite, appear everywhere. The long bead described above is worn with them, superimposed or suspended, as is the flat, oval bar, itself sometimes of similar squares. Amulets are often sewn on the collars, and at Copan, Tikal, Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, Seibal, Ixkun, Cankuen, and on jade plaques, are visible in threes, one in the centre and one on each shoulder.

At Yaxchilan alone is found a sort of muffler [Figure 11], of tubular material, feather or textile, that hangs about the neck like a scarf and is knotted at the level of the waist; a similar neck ornament is seen on a figurine in the Peabody Museum, and on the pottery a short section of the same material is fastened to strings that tie at the back of the neck, the puffy crescent thus formed in front being sometimes trimmed with knots and joined with an oblong bar. At Chichen Itza a Maya chief is holding, presumably as an offering, a bunch of these same long, tubular affairs, knotted at either end.

GIRDLE. A type of girdle found at all of these sites but Quirigua and Piedras Negras may be taken as the norm: fairly wide, generally of textile in a design which may have planetary significance, with a fringe of sea shells, it has in the front and at the sides large amulet heads with three shells hanging from each [Figure 12]. Variations may lack the side heads, may have the solitary head that of a jaguar, or may lack only the central head; again, girdles of varying design may be entirely without such heads. A strange, corsetted effect is produced by a girdle several inches wider than the tightly bound waist at Quirigua, Piedras Negras, Yaxchilan, Naranjo and Seibal [Figure 13, a]. A different type of girdle that appears most frequently at Palenque and is always associated with a long or short network skirt consists of long tubular beads, set vertically close together and edged at the bottom with round beads [Figure 13, b].

The long flap hanging from the front of the girdle that Spinden calls apron, may belong to the girdle or the loin cloth underneath it. Its most elaborate form, boasting one or more grotesque faces, with frets at the sides [Figure 14, a], appears at every site; lacking grotesques, at Copan, Quirigua, Ixkun and Yaxchilan. In other forms, it is unmistakably textile at Piedras Negras and Naranjo [Figure 14, b]; probably textile, decorated with beads carved into rosettes, at Yaxchilan, Palenque, and on jades [Figure 14, a]; and essentially bead at Copan, Tikal, Naranjo, Yaxchilan and Palenque [Figure 14, d]. At this site similar bead ornaments hang from the back of the girdle, sometimes shorter ones from the sides, and two carved chains from a man’s belt support a grotesque manikin swinging behind him. This occurs also at Tikal, where a grotesque head may be similarly hung from a seated figure on a lintel.

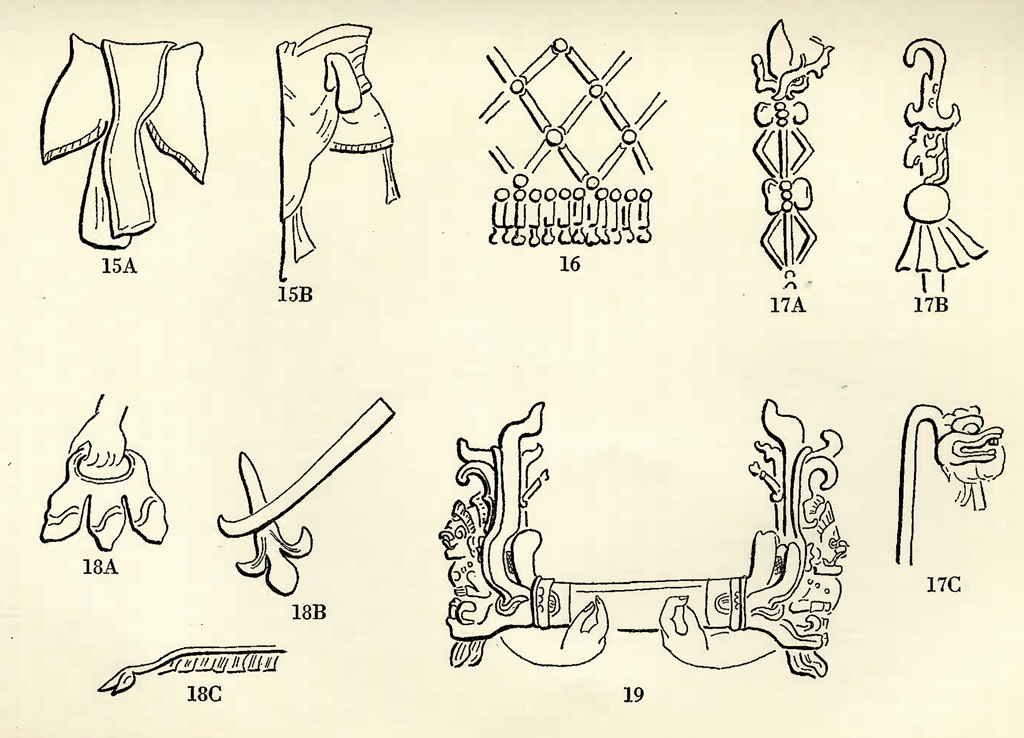

LOIN CLOTH. The traditional Maya loin cloth, that wrapped around the waist in a wide band with long ends before and behind, is shown on the pottery; a variety with front flaps and a shaped skirt [Figure 15, a], shown at La Mar, must have been worn under girdles and tunics, for we have skirts that undoubtedly belong to such garments, of textile at Yaxchilan and Piedras Negras, of network at Tikal, Piedras Negras and Palenque, of jaguar skin at almost every city. A loin cloth that wraps around with a long triangular apron front appears at Palenque, Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan [Figure 15, b].

SKIRTS, ROBES. Long skirts of the network that seems to be diagonally woven of round and cylindrical beads [Figure 16] are found alone at Copan and Palenque, over textile at Naranjo, and over jaguar skin on stela H at Copan. At Naranjo a long textile skirt is worn under a long feather cape; at Cankuen under an apparent network dress, much like the network garment covering a cat-faced figurine from Chamá. At Tikal, Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan elaborate robes, probably embroidered, are fastened over the shoulders [Figure 26].

CAPES. Short capes are of network at Copan, Palenque and perhaps Naranjo, of skin at Tikal and Yaxchilan. Feather capes are long in front at Naranjo and Piedras Negras, long behind at Tikal, apparently only over the shoulders at Copan, Piedras Negras and Naranjo [Figure 24, b]. At Yax-chilan and on two figurines in the University Museum occurs a cape, long behind, that may be feathered, quilted, or plain textile, and on a Copan stone figure in the Peabody Museum, there is a short, richly embroidered textile one.

Tunics, probably of the same close set squares of which collars were made, are worn at Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan; one of jaguar skin at Yaxchilan, and here also a woven variety with bead rosettes.

ACCOUTREMENTS. Almost every sculptured figure carries some object of practical use or religious significance. Military implements are fairly common; the spear appears in every city but Copan and Quirigua; a short one, resembling a javelin, is found at Naranjo, and the man on stela 2 at Cankuen carries a bunch of short javelins like those used with the atlatl. Ceremonial types include an openwork variety found also at Chichen Itza, as well as at Tikal, Naranjo and Itsimte Sacluk [Figure 17, a]; varying snake head kinds and one that ends in a hook, at Piedras Negras [Figure 17, b]; and long staves at Naranjo, Ixkun and Tikal. Shields, worn on the left forearm, are round and small, representing usually a human or grotesque face at Tikal, Quirigua, Ixkun, Itsimte Sacluk, Yaxchilan, Naranjo and on the jade plaques; larger and oblong at Piedras Negras, Naranjo and Can-kuen, and on a figurine from the Highlands of Guatemala. On a Chamá vase a large oblong shield stands behind the chief, and at Palenque a large round one stands before two crossed ceremonial spears. At Tikal, Yaxchilan and Tsendales, human or death’s heads are slung presumably as shields at men’s backs; the reverse of stela H at Copan shows what may well be intended for the same thing. At Yaxchilan we find a stone knife on lintel 26, jaguar claw clubs on lintel 6 and a feathered club on the deity side of stela 11.

Figures carry small bags or pouches of varying shapes and stuffs at Piedras Negras, Yaxchilan, Tsendales, Naranjo, Seibal, Palenque and Tikal; a foliated one on stela 30 at Naranjo [Figure 18, a] is duplicated in that carried by a Toltec at Chichen Itza; and an object of the same shape on a vase may be bag or fan. An axe with trefoil edge [Figure 18, b] occurs at Yaxchilan and Palenque; stave-like torches decorated with a Maltese cross at Yaxchilan; short cone-like torches at Yaxchilan and possibly on the pottery, and what may be torch or foliated stave at Yaxchilan on lintel 24; a round fan, long-handled and feather-edged at Yaxchilan, short-handled at Naranjo, and woven or braided on the pottery. A strange object is one made perhaps of feathers, perhaps of scales, carried in the hand on stela 13 at Naranjo and on a vase, and worn apparently suspended from the headgear on lintels 6 and 43 at Yaxchilan [Figure 18, c].

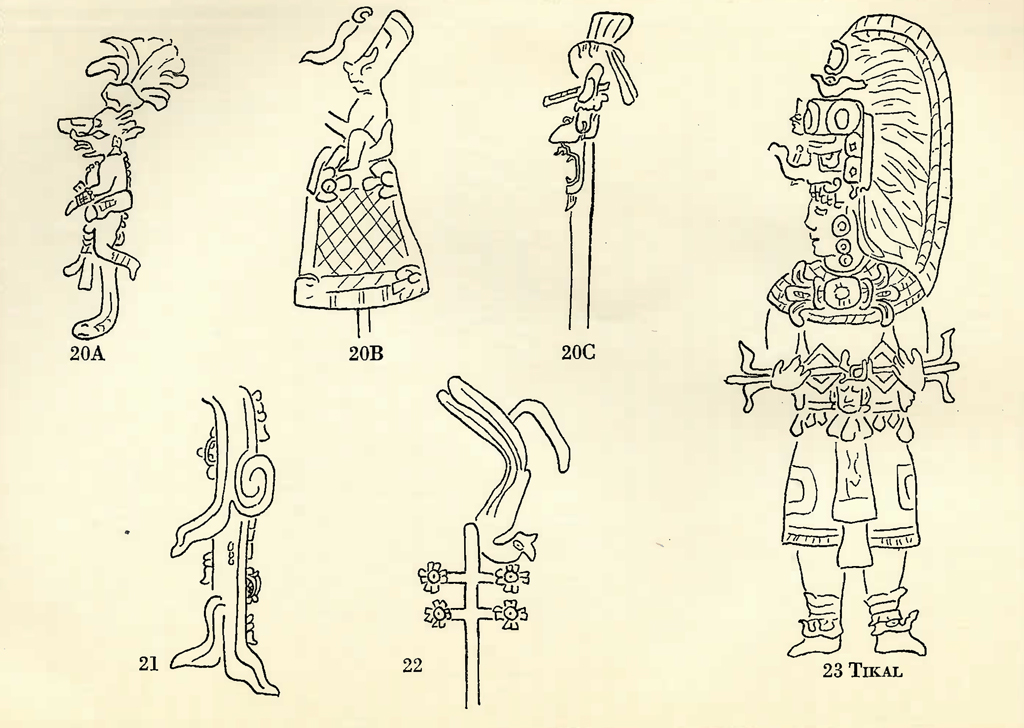

Religious importance is attributed to the Ceremonial Bar and the Mani-kin Scepter. The first, a short bar with a human head between the snake jaws [Figure 19], is found at Quirigua and Copan, the snake body a pendant curve on the three earliest stelae at the latter site. At Tikal, an entire figure rests in the serpent’s mouth. The bar is short without human heads in two Quirigua stelae; long and decorated with planetary signs at Seibal; the same, with masks in the serpents’ jaws, on stela 4 at Yaxchilan, and long with human heads but no symbols on the bar on stela 1, and at Naranjo. The second, in its usual form of the Manikin God held by his snake leg [Figure 20, a], occurs at Tikal, Quirigua, Itsimte Sacluk and Yaxchilan; at the last-named site the same god appears seated on a braided truncated cone that is mounted on a long staff [Figure 20, b], and it is probably he who, seated or reclining on a cushion, is held aloft on the sanctuary talets at Palenque. Here, at Tsendales and Piedras Negras, is found the form of the Manikin Scepter that is reduced to a head on a staff [Figure 20, c]; the child in arms at Palenque who has one leg a snake’s body and head may be another manifestation of the same deity. A type of flexible shield, probably representing water [Figure 21] (see Dresden Codex), seems to be an object of adoration at Yaxchilan, is held, in abbreviated form, by a worshipper and worn in a headdress at Palenque; and hangs from the jaws of the Ceremonial Bar snakes at Quirigua. A conventionalized tree with a bird at the top [Figure 22] is carried at Yaxchilan, a tree not so conventionalized on a jade plaque. A basket appears generally as an adjunct of the thorn-knotted penitential rope at Yaxchilan, but seemingly secular in its use at Naranjo and on the pottery; a small tied bundle is borne by minor figures at Yaxchilan; a feathered jaguar head is being presented to the possible god on lintel 26 at that city; and on a Chamá vase two men carry bones painted red on one end. A snake is held vertically by the figure on a Quirigua incense-burner and by both persons on a Palenque relief; a snake with a god issuing from his jaws appears first between two men, on Yaxchilan lintels, its body held by the man on the left, then, unsupported, to a solitary worshipper.

A mask is worn over the face of the principal figure on monuments at Copan, Tikal, Yaxchilan and Palenque; the object carried by the man on stela 8 at Seibal may be such a mask, and the scale arrangement close-fitting about the face on stela 11 at the same city [Figure 6, a] may be a degeneration or an impressionistic rendering of one. Small figures that may be related to those in the panel glyphs at Quirigua play about in the intricacies of the Copan and Quirigua headdresses [Figures 24, a and 25] and hover over the demolished head on lintel 5 at Piedras Negras.

II

In spite of this general distribution of articles of dress, there are costumes at each site typical of that city, and certain objects not yet found elsewhere.

TIKAL. Men at Tikal wear a snake mask headdress, collar with foliated bar, and a shell-fringed three-headed girdle over a skin or net skirt [Figure 23]. This is the only place where we find a headdress showing the wearer’s head between the realistic jaws of a scale snake [Figure 5, b]; where the openwork spear is held horizontally or aslant across the body; and where an entire figure rests in the jaws of Ceremonial Bar snakes.

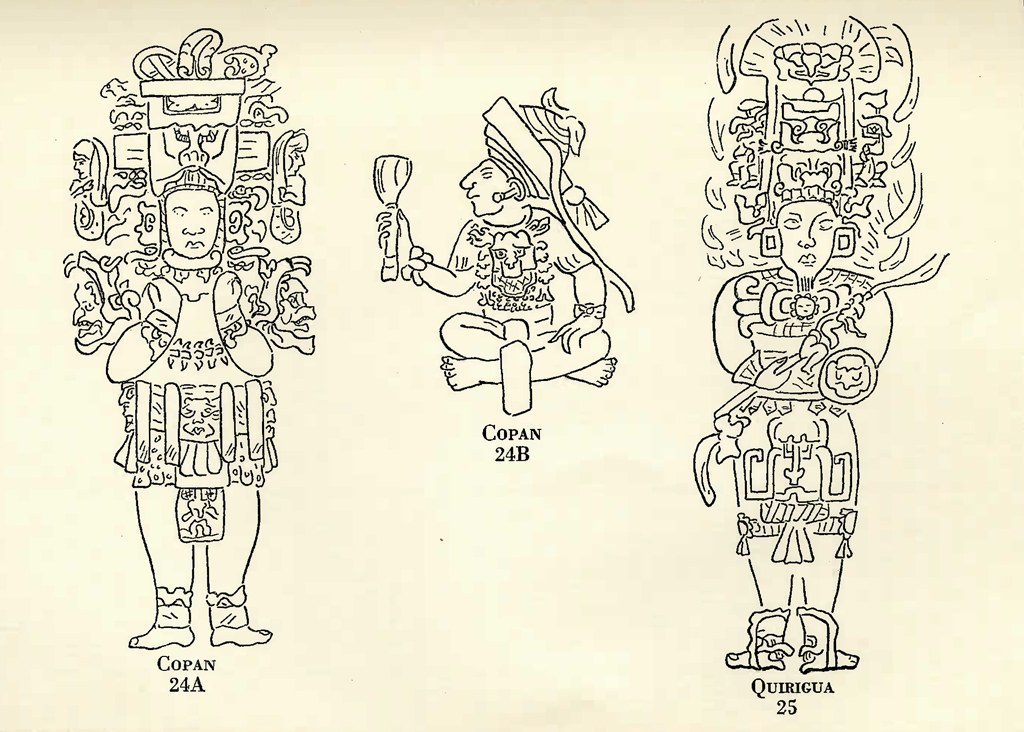

COPAN. At Copan there are two distinct divisions, the standing figures of the stelae [Figure 24, a] and those seated in rows about the altars and along the step found by Maudslay [Figure 24, b]. The men on the stelae wear towering headdresses, with tiny figures, sometimes animal-headed, popping in and out of the folds; shell-fringed three-headed girdles that here alone have straps — plain, knotted or grotesque hanging between the heads; sandals and cuffs that are adaptations of a snake’s head; square-set collars that are half-hidden by the Ceremonial Bars they bear. Only at Copan do we find this article with the bar replaced by a realistic snake body. Stela N seems to represent a water, presumably crocodile, deity; stela I shows a man in a mask (probably the face of God D, portrayed in the heads on his girdle) carrying a dead snake, with the three-member underworld symbol at the top of his headdress. On two stelae occurs the horizontally folded turban which is such a marked characteristic of the seated figures.

This turban appears on thirty-six of the forty-two figures on altars and step; two of the remaining six wear a round turban with the scroll front that is found nowhere else. The rest of their costume consists of the traditional form of loin cloth, and neck ornaments of the horizontal long bead — hung singly, in pairs, or three together — or two snakes, from whose knotted heads hangs a bead-fringed tau-shaped ornament that sometimes develops into a jaguar head; almost all wear short feather shoulder capes.

QUIRIGUA. The typical Quirigua costume [Figure 25] would be a high headdress of superimposed masks; a collar with three amulets or a scale foliated bar, the latter found where a Manikin Scepter is carried; a shell-fringed girdle with one central head and grotesque, fretted apron; bead knee bands with an amulet in front, and sandals with a grotesque face. A Ceremonial Bar is found here with water pouring from the snakes’ mouths. On the north sides of stelae A and C, that is, the side toward the mound before which they stand, are symbolical or masked dancing figures, with the head in profile, and with highly conventionalized girdle, headdress and Ceremonial Bar.

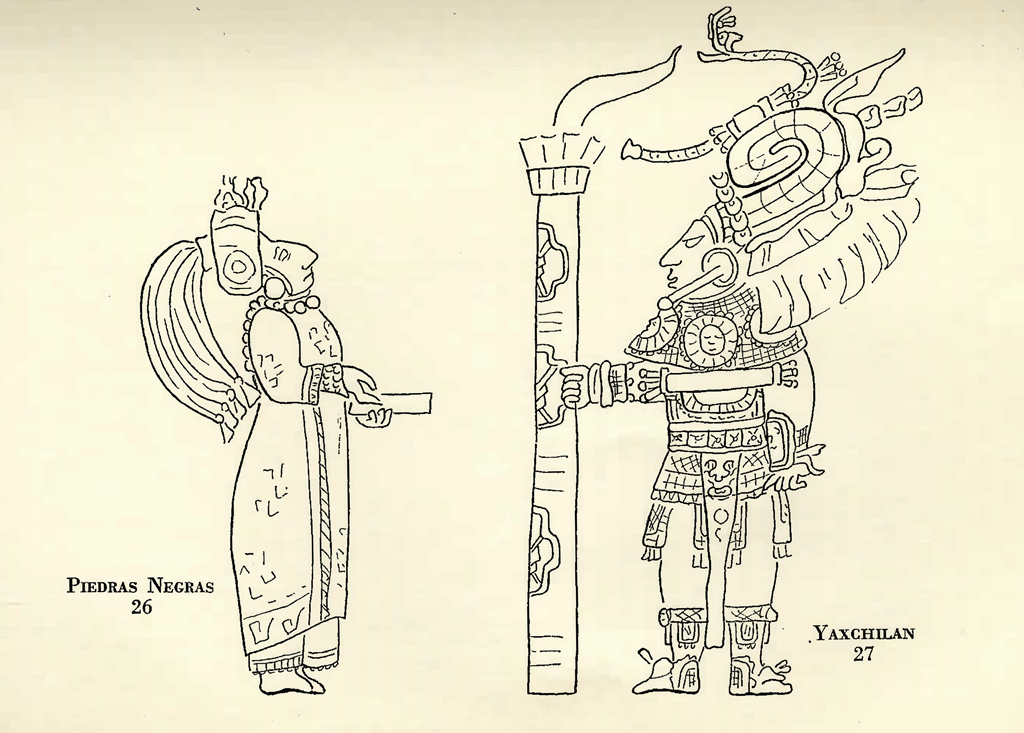

PIEDRAS NEGRAS. Only at Piedras Negras do we have definitely militaristic scenes. Lintels 2 and 4 both show a captain facing a file of soldiers; and stela 12 shows captives, guarded by soldiers, being presented to a chieftain by a presumable priest. Also at this city is a unique series of stelae that show persons of great importance seated in canopied niches. A man with a snake-snout headdress, with or without the geometrically conventionalized lower jaw, or in a vertically folded turban, wearing a collar and loin cloth with elaborate textile flap, or wrapped in a robe, would be characteristic of this site [Figure 26], as would one in a girdle of close set squares fringed with rows of shells, beads and perhaps embroidery, with skirt or loin cloth showing below, wearing embroidered knee bands, a collar of alternating round and cylindrical beads, a feather holder erect or on its side somewhere in his headdress, and carrying an oblong shield and a spear practical or ceremonial. Only here on the monuments do we see shepherd’s crooks ending in a snake’s head [Figure 17, c], and spear ends where a conventionalized snake god’s head becomes a sort of boat hook [Figure 17, b]. The coincidence of crook and headdress with lower jaw on stelae 26 and 31 makes one feel that they represent the same person. The chief warrior on lintel 2 and the figure on lintel 35 also strongly resemble each other, having identical collars, with an unusual border ornament, identical shields, bags, and textile aprons decorated with a four-petalled flower, and similar headdresses and girdles. These identical costumes on different monuments are in both cases dated within a few years of each other, which may indicate actual portraiture.

YAXCHILAN. At Yaxchilan the atmosphere seems to be almost exclusively religious; practically every carving shows a person receiving or holding ceremonial objects. Characteristic of this city are figures in reptile headdresses that seem more apt to represent the snake god K than an actual serpent, for the eye is almost always above the nose rather than behind it. They wear square-set knee bands, collars and long robes; or collars with three amulets, accompanied by elaborate headdress and varying girdles [Figure 27]. A characteristic girdle fits tight at the waist and flares below; one portion or the other is generally decorated with beads or the ubiquitous close-set square. Unique here are the bird and tree object [Figure 22]; the penitential rope; large stave-like torches decorated with Maltese crosses [Figure 27], and small cornucopia ones; and various elaborations of headgear such as the geometricized snakes of lintels 8 and 24, the striated textile headdresses referred to above, and applied long beads, openwork spears, and small superimposed shields. A tunic with rosettes probably of beads, is found only here, and with it there is always the muffler [Figure 11], that mysterious neck adornment peculiar to Yaxchilan. Twice, the man who wears them carries a flexible shield, once, a knife; where he wears a muffler but no tunic he holds a spear, and, on lintel 45, a spear and flexible shield. Only at this site do we have a snake appearing with a god issuing from his jaws. There are at Yaxchilan three cases of almost complete identity between figures on different lintels. The first, lintels 6 and 43, shows the main figure on each relief wearing an animal mask headdress with long beads attached vertically at the sides, a collar with three amulets and pendant long bead, a tied girdle with a jaguar head in front, what seems a bordered tunic but may be upper arm and thigh bands, elaborate amulet knee bands and sandals. They have nose plugs that turn up with a flare at one end; a strange feather or scale chin strap, or pendant from the headdress, and carry the beehive type of Manikin Scepter. In the second case, lintels 1 and 42 show the main figure — on one lintel turned away from the lesser, on the other turned toward him — wearing a striped or folded textile headdress with two superimposed small shields and a long bead at the side, a collar with three amulets and pendant bead with a semi-circular flap hanging from it, a flaring girdle with tabs below it, scale knee bands, sandals, holding in the right hand a Manikin Scepter, on the left wrist a round shield. In the third case, lintels 3 and 7, both figures have headdresses of a curled snake tail surmounted by three beads and two more tails, shell-fringed girdles with three heads, fretted aprons, a round shield on the left wrist and a Manikin Scepter in the right hand. Here, as at Piedras Negras, identical costumes are dated close together. The fragments of stelae 1, 4 and 6 also bear a strong resemblance to each other: at the top, we see sun and moon glyphs on either side of a mask; below, a figure with a human head slung at his back wearing a collar with three amulets, a girdle without heads, and a bead apron, holds a flexible shield [Figure 21] over a knotted and woven object that may be drum, altar or table. Offerings are laid on a similar object in a secular scene on a Chamá vase.

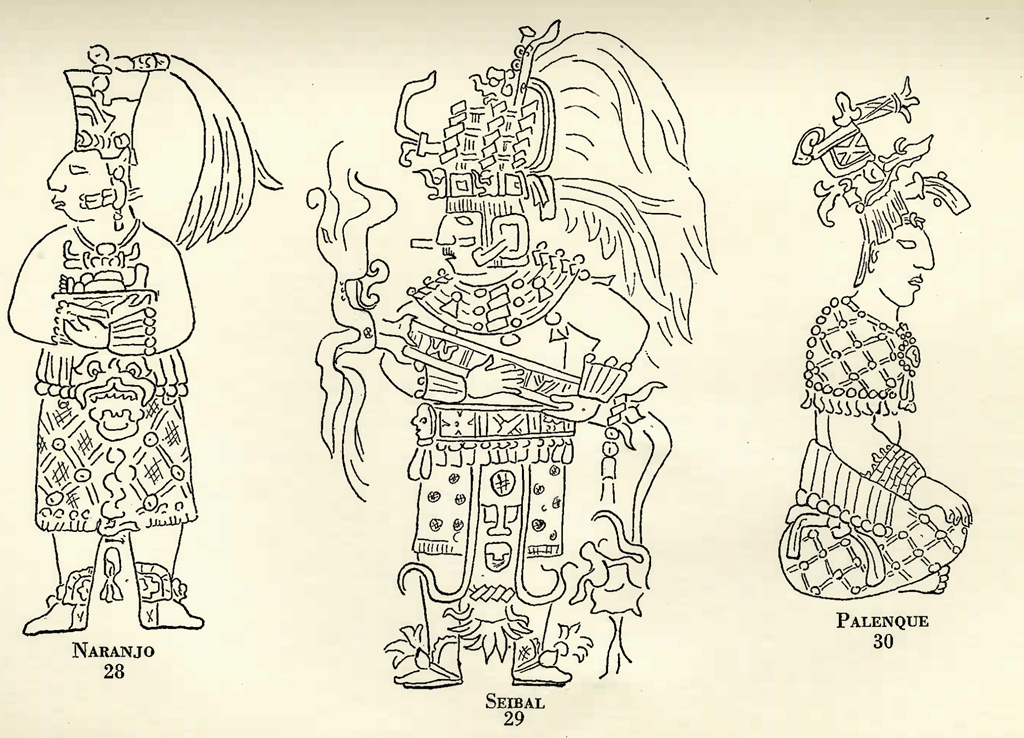

NARANJO. Characteristic of Naranjo is a figure in a snake or snake god headdress and a long net-over-textile skirt, carrying a filled basket [Figure 28], or else one rather like Tikal but holding aslant a long Ceremonial Bar with human heads in the snake jaws.

SEIBAL. A man wearing a collar with three suspended amulets or one made of beads in a zigzag pattern, a girdle of planetary symbols with heads at the sides, and a grotesque apron with rounded frets over a short skin skirt, whose compound visor type of headdress is built over a helmet probably of false hair, and who carries aslant a Ceremonial Bar, long and decorated with planetary signs, would be from Seibal [Figure 29]. A bib-like collar, one with a strange foliated front ornament, and a radiating beaded one, are peculiar to Seibal as is the prolonged neck bar on stela 1. Stelae 5 and 7 wear the skirted loin cloth as at La Mar, and a large, twisted bar, broken at one end, apparently glued to their chests.

PALENQUE. The characteristic dress of Palenque [Figure 30] would be a short or long net skirt and a net cape, a girdle of long tubular beads edged with round ones, hair drawn up and banded with or without supplementary trimming. The costumes on the sanctuary tablets are unique: tall cap, bead necklace and apron or shaped net loin cloth for the priest; for the worshipper, a cap with embroidered flaps, and a cloth garment that covers him from hips to neck, whence it falls in a twisted rope down his back. Here, in the (ceremonial) spears on the panel of the Temple of the Sun, is a new variety whose point is an enlarged and decorated tooth of the ubiquitous God K. Here also we make definite contact with the gods of the codices. God D, the Roman-Nosed God, probably Itzamna, appears on the east side of the sanctuary entrance in the Temple of the Cross in a costume — a jaguar skin cloak, a textile strip neck ornament, with a padlock-shaped pendant hanging from it, and a headdress in which the head of the Moan bird is the predominating element — practically identical with that which he wears while supporting the left side of the altar on the sanctuary tablet of the Temple of the Sun. At the right side of this altar, however, his attributes are essentially reptilian; the neck ornament is the same, but the headdress is a snake head one, and the god wears a dorsal strip with cross-hatchings.

III. Conclusions

Although scarcity of material makes generalization dangerous, scenes on the pottery, clearly those of daily life, that show even nobles wearing only headdress, necklace and loin cloth, emphasize the ceremonial character of the clothing on the stone reliefs. The quasi-sacred nature of such costumes may account for the apparently static fashions during a period of four hundred years, as witness the clerical robes of to-day. The variations in costume, therefore, are local rather than chronological. Hence, the appearance in only two or three places of articles of costume which are neither confined to one site nor yet widely distributed, shows a perhaps significant contact between cities where there is as yet no other proof of close interrelation.

The network clothing that makes the characteristic costume of Palenque [Figure 30] so distinctive is not limited to that city alone, for capes, long skirts, and short skirts appear plain or over a skin or textile foundation at Tikal, Naranjo, Xupa, Piedras Negras and Copan, while a figurine from Chamá, and a stela from Cankuen show what seem to be complete dresses of this material. Always, however, except at Xupá, a small town not far south of Palenque, and at Copan, the use of network is, according to our evidence, an adaptation, not a duplication of the Palenque style, for it takes forms not found at Palenque, and omits the typical combination of long skirt and cape with a long bead girdle. At Copan this occurs twice, on monuments probably erected within a year of each other; stela H, strikingly different from all the other stelae, and altar T, where the persons wearing this costume seem to be in the retinue of two men in a costume more characteristic of Copan itself. They are interspersed with bird and animal headed creatures and may be taking part in a dance or some other religious rite. The cat-headed figurine from Chamá may similarly be a masked dancer. These isolated occurrences at Copan, at the beginning of the sixth century, of a costume identical with that characteristic of Palenque would seem to prove that the latter was a flourishing city with far-flung relations of trade or war by A. D. 523. It is interesting to note in this connection a figurine, in the Peabody Museum, of a woman in a blouse of similar openwork diagonal weave, but obviously cotton, resembling in fact Sahagun’s description of cotton clothing worn by the sixteenth century Mexicans.

Palenque and Tikal share two unique adornments: the manikin figure swinging behind a sculptured personage by chains from the side of his girdle, and the neck ornament of woven textile strips [Figure 9, g]. The latter is an object interesting in its connotations. On Chamá pottery this occurs as a design on a necklace, and it is repeatedly used as decorative detail in costume in the carvings of Copan, Palenque and Quirigua. In the codices it occurs as a mat, from which Dieseldorff calls it the Pop motive from the Maya name for mat. If there were any basis for this connection, one would expect to find the braided motive in the glyph for the month called Pop; and here it indeed occurs, in the form of the glyph used on the monuments — its only occurrence among the glyphs. The Maya title for prince was Ahpop — hence this symbol would seem to indicate authority and princely position wherever it appears. The stela at Tikal on which it is worn as a necklace is early A. D. 215, according to Spinden’s correlation — and one would like to think that, since the necklaces at Palenque are its only other appearance in this form, there must be some close connection between them. The question, however, of the age of the Palenque temples is as yet unsettled. The dates on them are fairly early, ending in the middle of the fifth century, but according to the architectural development of the Guatemala cities, Palenque is the latest and most highly developed of all; hence it has been thought that the temples there were erected toward the end of the Old Empire and that the dates recorded refer to events far in the past. Be that as it may, the Pop neck ornament may prove a link between Palenque and the early Empire. An ornament on a Seibal headdress of two interwoven double-headed snakes probably derives from this motive, and is practically identical with the woven snake motive used in Mexican art with Tlaloc, Coatlicue and other deities.

Feather garments appear only at Tikal, Copan, Piedras Negras and Naranjo, though a cape of dubious fabric may include Yaxchilan; and embroidered robes only at Tikal, Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan. There is a headdress with rosettes in front and a sort of hinged elbow behind [Figure 7] that occurs only twice, once at Piedras Negras, A. D. 442, and once at Tikal, A. D. 481. This may mean close contact between these cities, monuments erected to a hero whom they shared, or merely that we know only two examples of a widely distributed form of headgear. In the same way the resemblance of a solitary puff ball turban at Piedras Negras [Figure 3, c] to those on the pottery from Chamá and Nebaj may or may not be important. The openwork spear [Figure 17, a] is found only at Tikal, Naranjo and It-simte Sacluk, though it reappears at Chichen Itza. Piedras Negras, Yax-chilan and Cankuen show a warrior in a snake tail headdress, and the harness, also found at Naranjo, that may be textile or closely woven beads, and includes skirted girdle, possible tunic, and, at the last three sites, tabs hanging from the shoulders and the sides and front of the girdle. The man at Naranjo holds one javelin just like the three on the Cankuen stela, and has a shield of the same shape though bearing a different design. These javelins are short, the only short ones on the old Empire carvings, and identical with those carried for use with the atlatl by the Toltec warriors on the Chichen Itza Tiger Temple frieze. There is, however, no representation of the spear thrower itself, unless it should be the partly obliterated object in the right hand of the Cankuen warrior.

A new element enters in the identification by costume of deities or historical personages. The cases cited of identical costumes on different monuments seem to show human beings rather than divine, with the exceptions at Yaxchilan of the man holding a flexible shield over a possible altar on stelae 1, 4, and 6, and the frequent man-in-a-muffler, whose companion almost always kneels before him. There is no sure clue as to which gods these are, if gods they be, nor can we be certain as to whether they show the god himself or merely a priest in divine regalia. The startled attitude of the worshipper on lintel 16 at Yaxchilan, however, might well indicate his reaction to the personal appearance of a god.

But at Palenque we seem definitely to have three appearances of God D. He is portrayed in the two figures supporting the altar on the Temple of the Sun tablet: on one side dressed as he is on the doorway in the Temple of the Cross, on the other still with the textile strip symbol of authority at his neck, but with the rest of his costume showing snake attributes instead of jaguar and bird ones. These Atlantean figures thus seem to show this deity in two manifestations of his role as sky god. The feather crown headdress surmounted by a bird head that he wears on the Temple of the Cross doorway is duplicated by that of a god, apparently N, God of the End of the Year, on a vase from Kixpek.

——

This, then, is a study handicapped by scarcity of available material that yet does offer definite possibilities for throwing light on the vexed question of Maya history. Even negative evidence is valuable, for it can show us that the variation in costume is local rather than chronological, thereby indicating influences and diffusions from one city to another. If further finds should show that present apparent differences between costumes of cities of the Old Empire are non-existent, that would at least be a definite proof of cultural uniformity.

Something may be learned of the interrelation of the Old Empire with Yucatan by comparing carvings from the Peninsula with those from the Guatemala cities. The occurence of apparent atlatl darts in the equipment of warriors of the Old Empire, for instance, will, if substantiated, mean either that Toltec influence was felt in Guatemala long before the days of the Yucatecan league, or else that this weapon, supposedly characteristic of the Nahua people, was early known to the Maya as well.

The cases of identical costumes on different monuments are so far rare enough to permit the idea that they are actual portraits. If they should prove, however, with more material, to be merely costumes typical of, perhaps, certain orders of priests or warriors, that, in itself, should help in interpreting what we know of Maya history and social organization. For this, carvings and paintings that show two or more persons are more valuable than those with only one, for the interrelation of the figures is often an indication of their respective status.

Study of the gods of the codices, where they can be identified in the archaeological material, may throw new light on their proper classification, for here their costumes seem to be more comprehensive and more suggestive of their divine attributes than those they wear in the codices.

The possibilities of this line of research are, therefore, varied enough to warrant further investigation.

Appendix

Features Each City Has in Common With Each Other City, and, Below, What Those Features Are

| T | C | PN | Y | N | Ts | IS | Q | Ck | I | S | P | Py | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tikal | – | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | 4 | 2 |

| Copan | 3 | – | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1 | – | 4 | 1 | – | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Piedras Negras | 5 | 5 | – | 4 | 4 | 1 | – | 1 | 2 | – | – | 3 | 1 |

| Yaxchilan | 2 | 1 | 4 | – | 3 | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | 2 | 4 |

| Naranjo | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | – | – | 1 | – | 2 | – | – | 2 | 4 |

| Tsendales | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| Itsimte S | 1 | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Quirigua | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cankuen | – | 1 | 2 | – | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| Ixkun | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Seibal | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Palenque | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Pottery | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Copan | Tikal | Round turban, chin strap, back shield. |

|---|---|---|

| Yaxchilan | Back shield. | |

| Naranjo | Short feather cape, net cape and long skirt, inflexible necklace. | |

| Quirigua | No skirt, snake jaw chain, elves,* inflexible necklace. | |

| Tsendales | Back shield. | |

| Cankuen | Long net skirt, snake snout on shield here | |

| Seibal | Inflexible necklace. | |

| Piedras N. | Copan | Snake snout headdress, short feather capes, lower jaw headdress, round turban, elves. |

| Tikal | Long feather cape, robes, short net skirt, round turban, hinged elbow headdress. | |

| Yaxchilan | Girdle, beads; apron loin cloth, robes, snake tail headdress. | |

| Naranjo | Short feather cape, long feather cape, leaf necklace, shell orna¬ment. | |

| Tsendales | Head on staff. | |

| Cankuen | Bead girdle, snake snout on Ck. shield, snake tail headdress. | |

| Quirigua | Elves. | |

| Palenque | Piedras N. | Head on staff, short net skirt, apron loin cloth. |

| Tikal | Short net skirt, woven ornament, swinging back figure, chin strap. | |

| Copan | Long net skirt, net cape, chin strap, snake jaw chain. | |

| Yaxchilan | Apron loin cloth, axe. | |

| Naranjo | Long net skirt and cape. | |

| Cankuen | Long net skirt. | |

| Tsendales | Head on staff. | |

| Naranjo | Tikal | Openwork spear. |

| Yaxchilan | Fan, basket, tabbed warrior costume. | |

| Cankuen | Javelin, tabbed warrior costume. | |

| Itsimte S | Openwork spear. | |

| Yaxchilan | Tikal | Short skin cape, manikin scepter heald by snake leg. |

| Quirigua | Itsimte S. manikin scepter held by snake leg. |

Occurring on old Empire reliefs:

| In 4 cities. | |

|---|---|

| Net cape and long skirt | C, N, P, Ck |

| Back shield | T, C, Ts, Y |

| Inflexible necklace | C, Q, N, S |

| Manikin scepter (usual form) | T, Q, Y, Is |

| In 3 cities. | |

|---|---|

| Robes | T, PN, Y |

| Short net skirt | T, PN, P |

| Openwork spear | T, N, IS |

| Round turban | T, C, PN |

| Chin strap | T, C, P |

| Short feather cape | C, PN, N |

| Snake jaw chain | C, Q, P |

| Head on staff | PN, Ts, P |

| Snake tail headdress | PN, Y, Ck |

| Tabbed bead(?) girdle | Y, N, Ck |

| Long feather cape | T, PN, N |

| In 2 cities. | |

|---|---|

| Hinged elbow headdress | T, PN |

| Woven neck ornament, swinging back figure | T, P |

| Skin cape | T, Y |

| No skirt | C, Q |

| Elves, lower jaw snake snout headdress | C, PN |

| Shell ornament, leaf necklace | PN, N |

| Tunics | PN, Y |

| Axe | Y, P |

| Fan, basket | Y, N |

| Javelin | N, Ck |

Any object occurring more than four times is considered too frequent to be significant.

Probable Dates of Erection of Monuments Cited

Spinden-Morley Correlation

| Tikal | |

|---|---|

| A.D. | |

| Stela 9 | 215 |

| 5 | 484 |

| T2 11 | 487 |

| Stela 16 | 503 |

| Altar 5 | 503 |

| Copan | |

|---|---|

| Stela P | 363 |

| 2 | 388 |

| I | 407 |

| C | 470 |

| A | 471 |

| B | |

| D | 476 |

| N | 501 |

| Altar L | 502 |

| Step | 503 |

| Altar T | 523 |

| Stela F | 523 |

| H | 524 |

| Stela 11 | 516 or (?)570 |

| Yaxchilan | |

|---|---|

| A. D. | |

| Stela 6 | 396 |

| 19 | 472 |

| Lintel 9 | 476 |

| 15 | |

| 26 | 477 |

| 42 | 480 |

| 14 | 481 |

| Stela 5 | 484 |

| Lintel 46 | 486 |

| 33 | 487 |

| 1 | 492 |

| 5 | |

| 7 | |

| 16 | |

| Stela 11 | |

| 20 | 494 |

| Lintel 3 | 496 |

| Stela 18 | |

| Lintel 2 | 497 |

| 6(?) | |

| 8 | 500 |

| 24 | 501 |

| Stela 1 | |

| Lintel 32 |

| Naranjo | |

|---|---|

| A. D. | |

| Stela 3 | 422 |

| 28 | 431 |

| 20 | 434 |

| 24 | 442 |

| 22 | |

| 21 | 447 |

| 23 | 452 |

| 2 | 453 |

| 29 | 455 |

| 30 | |

| 31 | 462 |

| 18 | 466 |

| 5 | 472 or 524 |

| 13 | 526 |

| 14 | 530 |

| 12 | 540 |

| 6 | |

| 11(?) | 543 |

| 8 | |

| 7 | 550 |

| 32 | 560 |

| Tsendales | |

|---|---|

| Stela | 432 |

| Itsimte Sacluk | |

|---|---|

| Stela 1 | 452 |

| Quirigua | |

|---|---|

| Stela H | 491 |

| Altar L | 493 |

| Stela F | 501 |

| D | 506 |

| E | 511 |

| C | 516 |

| A | |

| K | 545 |

| Cankuen | |

|---|---|

| Stela 2 | 530 |

| 1 | 535 |

| Ixkun | |

|---|---|

| Stela 1 | 530 |

| La Mar | |

|---|---|

| Stela 1 | 523 |

| 2 | 545 |

| Seibal | |

|---|---|

| Stela 7 | 540 |

| 8 | 590 |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 1 | 609 |

| 2 | (?) |

Notes

The map is after Morely.

A drawing of the stela at Tsendales will be found, Figure 232, in Spinden, page 197.

A drawing of the figure at Xupá, is in Maler, 1901, page 21.

Jades referred to are, unless otherwise stated, in the Peabody Museum, Cambridge, Mass. The Gann jade plaque is figured in Joyce, 1927, page 171. Figurines are in the University Museum, Philadelphia.

The drawings are from the following sources:

- Gordon, pl. 8

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 11 (d)

-

- Maudslay, I, pl. 92 (6)

- Maler, 1901, pl. 13

- Maler, II, p1. 32

-

- Maudslay, II, pl. 84

- Maler, 1901, p1. 31

- Maler, 1903, pl. 38

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 81

Page 158

-

- Spinden, 1913, fig. 24

- Maudslay, III, pl. 78

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 71

- Maler, 1901, pl. 23

- Maudslay, I, pl. 34

Page 161

-

- Maler, 1908, pl. 9

- Maler, 1911, pl. 28

- Maudslay, II, pl. 92

- Maler, 1901, pl. 14

-

- Spinden, 1913, fig. 1 (b)

- Spinden, 1913, fig. 83

- Maler, 1903, p1. 72

-

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 11 (e)

- Maler, 1903, pl. 49

- Maudslay, II, pl. 36

- Maler, 1908, pl. 20

- Maudslay, II, pl. 25

- Maler, 1901, p1. 21

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 81

- Gordon, p1. 30

Page 162

- Maler, 1903, pl. 49

- Maudslay, II, pl. 84

- Maudslay, I, pl. 82

-

- Maler, 1903, pl. 74

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 10

-

- Spinden, 1913, fig. 15 (a)

- Maler, 1901, pl. 28

- Maler, 1903, pl. 73

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 36

-

- Maler, 1903, pl. 36

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 76

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 36

-

- Maler, 1908, p1. 23

- Maler, 1901, pl. 17

- Maler, 1901, pl. 23

-

- Maler, 1908, pl. 42

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 36

- Maler, 1903, pl. 50

- Maudslay, I, pl. 82

Page 166

-

- Spinden, 1913, fig. 47 (a)

- Maudslay, II, p1. 95

- Spinden, 1913, fig. 50

- Spinden, 1913, fig. 84 (c)

- Spinden, 1913, fig. 103

- Maler, 1911, pl. 26

Page 169

-

- Maudslay, I, pl. 63

- Maudslay, I, pl. 92

- Maudslay, II, pl. 36 (b)

Page 171

- Maler, 1901, pl. 20

- Maler, 1903, pl. 63

Page 173

- Maler, 1908, pl. 39

- Maler, 1908, pl. 8

- Maudslay, IV, pl. 10

Bibliography

| Dieseldorff, E. P. | A Pottery Vase with Figure Painting from a Grave in Chamá. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 28, page 639. |

| A Clay Vessel with a Picture of a Vampire-headed Deity. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 28, page 665. | |

| Kunst and Religion der Mayavölker. Berlin, 1926. | |

| Förstemann, E. | The Vase of Chamá. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 28, page 647. |

| Gordon, G. B. | A Study of Maya Pottery. Philadelphia, 1925. |

| Joyce, T. A. | Mexican and Maya Art. London, 1927. |

| Maler, T. | Explorations in the Department of Peten, Guatemala, and Adjacent Region. Explorations of the Upper Usumatsintla and Adjacent Region. Peabody Museum Memoirs, Vol. IV. Cambridge, 1908. |

| Researches in the Central Portion of the Usumatsintla Valley. Peabody Museum Memoirs, Vol. II. Cambridge, 1901-03. | |

| Explorations in the Department of Peten. Peabody Museum Memoirs, Vol. V. Cambridge, 1911-13. | |

| Maudslay, A. P. | Biologia Centrali-Americana. London, 1899-1902. |

| Seler, E. | The Vase of Chamá. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 28, page 651. |

| Spinden, H. J. | A Study of Maya Art. Peabody Museum Memoirs, Vol. VI. Cambridge, 1913. |

| Unpublished MS in Peabody Museum on Dates on Maya Monuments |