Before me stands an old American Indian basket, it is a production of my own people. As I look and study its dilapidated form I feel as if it recognizes me, and my thoughts flash across thousands of miles, back to the land where we both belong, and then back to the age stained old piece before me. It seems to me that I have seen this before. Is not this the old “Rest-in-shadow”? It may be that I only heard of it when I was yet too young to remember important things.

The basket was brought in to me, to write and tell about it, and after I dipped my pen in the ink I held it and wondered: “How am I to begin?” Now, for once I realize that I am handicapped in not knowing enough about one of the important things made by my own people.

Basketry is the woman’s handiwork, and at one time a man felt rather clumsy when he started to talk about the dainty composition, but, since the white people came to our land, most of us have learned that to know about many other things beside the aggressive arts is necessary. Hence, a man with modern education often times tries to make up with the woman for his former inconsiderate conduct, by consulting her on the methods of basket making, but a true Tlingit woman, like a disturbed clam, still has her lips closed tight upon her feminine thoughts in the presence of him whose idea alone had demanded all praises, and usually with a smile tells him to mind his own affairs. Hence, the description of this article shall be confined within the limits of a Tlingit man’s knowledge of the art, and, aside from the occasional use of native terms, no attempt is made to offer in detail the methods of weaving the basket.

Museum Object Number: NA3351

Image Number: 12593

From the beginning of its history the woman’s root basket had always held its own among the most important things invented for use in the economic life of the Tlingit people, and if anything deserved praise the art of basketry was entitled to at least some credit. But it was the former majestic attitude of the man that repelled in the woman her desire for consultation with her lord whose favor she had always sought. The basket was indeed a useful thing with him, but little did it occur to his selfish mind that it required great skill to produce it; to him the work was the result of a mere woman’s mind. Therefore, in spite of all disappointments the forlorn woman continued to perform quietly all that her skill could produce. Thus, the knowledge of the art was conveyed to our time only by the unerring patience and faithfulness of the old time Tlingit woman.

The life of the white man came over the Tlingit people like a great thunder storm, and in the wake of this the man found that all his old occupations in which he had excelled had been destroyed; thus all hopes within him began to disappear; the pride of excellence remained, however, with the woman: which is a good test that she easily surpassed the woman of the other race in the work she was allowed to continue. An invader may satisfy himself in saying that the native customs and habits have about disappeared, but could the lid of the true Tlingit woman’s mind be thrown wide open there would be seen the mystic veneration of her art still alive and active.

Geographic Divisions.—We have learned that after the Tlingit speaking people entered the land which is now known as Southeastern Alaska, they began to scatter. Only one group, comprised of close relations, made its settlement at the first landing, which they had referred to as Sä-niya “West-side” (of the Portland Canal). Most of the people continued their search westward for a more favorable place to call a home, and as the migration proceeded up along the coast, various groups found their way to some island, river, or inlet.

Years passed, but a man of Säniya-quan’ “Westside-people” lives to hear, from time to time, of his kin who had wandered elsewhere, only by a new geographical name; the names which, from that day to this, have clung to them like scars, never to be erased.

The divisions which met with fortune (and each eventually became an independent body) are: Tōn-yätug’-quan on the land named Tōn “Sealion” which is now known as Rivillagigedo Island; Henya-quan’ “Waterside-people” (i.e. the ocean side of the Prince of Wales Island); Shtug-hin-quan’ (Stikine people), Kuyou-quan’, on the Kuiu island; Kekä-quan’ on the land they named Kekä “Opening of day” (dawn) which is now known as Kupreanof island; Sheetika-quan’ “Shee-outland people ” (Sitka people) on the land they named Shee, which is now known as Baranoff island; Whonah-qa’wu “Northwind side-inhabitant” on the northern shore of the land which is now known as Chichagof island; Whoozdäh-quan’ (modification of Whooz-noowu’-quan) on the land they named Whooz-noowu’ “Grizzly-bear-fort” which is now known as Admiralty island; Auku-quan’ “Little-lake-people” (Auke Bay); Jihlkot’-quan’ found their way into the river named Jihlkot’ (modification of Chähl-haut’ “cached-salmon” which is Anglicized as Chilkat); Hlähäyik-quan found their way into the bay they named Hlähä-yik’ (cf. Hlähä, Tsimshian term for, on high or highest), which became better known as Yakutat Bay. There are few more geographical occupations, and the foregoing list includes only groups among which the art of basketry developed.

It was not in a few years time that all these divisions were settled; many generations came and went. With the old passed to the Great Beyond some things of which we hear only in the legends, and in lieu of these the succeeding ones brought with them new things. Most of these served until something else appeared with more means of advantage, but it required the European civilization to put the woman’s root basket out of its long service.

Through all the years of unsettled life, arriving in one place, and leaving again for another, the women never lost sight of their coils of roots, and wherever a settlement was made a woman twined them into some useful form. Thus, they continued to make the baskets throughout the whole region. The same material and method in construction were employed, but with the progress of time, like other useful objects, each locality made a basket to serve its own purposes.

Image Number: 12668

Diversity of Forms.—The Great Raven, during his journey, transformed the land on which we live in different places. He made one place hard, while he smoothed out an easy way at another; he provided plenty here and less there. Thus, the ways of doing things are according to man’s environment. Yet with all these differences of habits he was wont never to forget his tradition. He may be of Jihlkot’-quan’ or of Hlähäyik-quan’; he is, nevertheless, a Tlingit. His geographic position never caused his tradition, language and customs to be different from those of his kin who had only settled on their own choice of land. But when it comes to providing accommodations for domestic life, what one uses with success in one’s own locality does not always meet with the same success in another. Hence, geography had much to do with the old time Tlingit enterprises.

In his own locality each man invented things, or modified things that had been invented in another, to suit his own purpose, and an object regarded for its utility at one place was sometimes regarded for its purchasing power at another. Thus, the use of basketry was either industrial or ideal.

On the one hand the form in basketry was decided at the outset, not by the desire to create something artistic, but to produce a useful receptacle, while on the other, the creation was done with a kind of aesthetic feeling, thus, its usefulness was often sacrificed to the desire to produce something beautiful. For example, there were the Jihlkot’-quan’ and the Hlähäyik’-quan’, the two geographical groups with whom the making of baskets offered a distinction.

With the Jihlkot’-quan’ the basket was a useful utensil: therefore its durability had remained foremost in the mind of the maker, and only leisure thoughts were spared to its artistic quality; the forms were limited to the most useful receptacles. The excellencies of weave and symmetry, however, were not entirely absent among the women—a fine basket went in company with the personal name of its maker.

With the Hlähäyik’-quan’ the industry in basketry has ever been of commercial importance, hence, the highest virtue of the woman was her ability to produce a beautiful basket, and it was always on the artistic quality of the production depended the efficiency in exchange. The piece for common use then was the despair of the expert weaver; it was bereft of ornament. Thus, the Hlähäyik’-quan’ women were foremost in the native art, and had the recent popularity of basketry but come in the days of native wealth they would have become also controllers of important means of trade.

Although no local difference was recognized in the construction of Tlingit basketry, a proud owner was often heard to say: “It is a Hlähäyik’-quan’ production,” indicating the people of the locality where basketry was regarded for art’s sake.

Museum Object Number: NA9214

Basket Maker.—It can be seen in most of the examples illustrated that in producing her effects the basket maker must have been well equipped for her work even before the first twist was attempted. The finest weaves show that every detail in the production was placed correctly during the progress of the twining, and when the work was finished there was no way to remedy defects, except by the possibility of raveling.

It was instinct which led the basket maker to search the forests and dig into the earth for the khät. She seemed to know in each section which plant furnished the toughest and most pliable root, the location in which it lay, and when it reached its best.

Basket Material.—Khät are the roots of plants, and it is the roots of the young and healthy seet (spruce) which they say are preferred, as offering the most desirable kind in pliability and uniformity in texture. In the spring of the year, when the sap began to run, it was a common thing to see women pass from tent to tent, making up a party to go “khät tearing.” It seems that the preparing of the khät is an industry left to a certain class of women. One often heard an expert weaver recommending to another, thus: “khät prepared by so and so are always nice, long and uniform in size, and the surfaces are never injured.” You might guess as well as a Tlingit man the meaning of all this.

In the summer camps it was also a common thing to see, suspended near some tents, strings of cut stems of various kinds of green grasses, hung out, as I have learned, to season and bleach. These the basket makers called shock’.

Basket Designs.—The basket has now passed into modern trade. The skill and taste, which at one time were put to the manufacturing of the merely useful receptacle, now lead to the making of choicest shock’ with which to bring out the desired designs as accurately as possible, and with this adaptation, the old time, self color “hat brim” pattern which, in Chilkat, was the only ornamentation seen on the border of some burden baskets, found itself among a multitude of new patterns which are worked with colored shock’ in the weave which is called false embroidery. This is a method of ornamentation in which the outer surface of the Tlingit twined basket is covered wholly or in part with the designs, which, however, do not show on the inside. The weavers call this yädä-shock’ “surface-entwining.”

As the knowledge of designing with the shock’ extended down through the region occupied by the Tlingit people, there was no end to the things which, appearing each right after the other, suggested new forms of patterns. There were the natural features of objects, such as plants, mountains and rivers; animals or parts of animals; if an entire creature could not be shown some minute part would represent it. All these ideas were exchanged among the weavers, and some were sometimes changed to suit the whim of the buyers. All these various ideas in designing in turn created among the women an emulous feeling in aesthetic ideals and technical skill, which became a potent factor in refining the art of designing. But the method of construction has not been improved upon. There are in the possession of some old families, baskets that were made prior to the intrusion of the white peoples. The forms and designs on these are similar to many now made. This indicates that the art has kept, to a great extent, its old time purity.

Museum Object Number: NA9219

Image Numbers: 12666, 12665

Coloring Basket Material.—With the development of yädä-shock’ came coloring. There came into use the first natural pale yellow, which was turned to various shades after the “wolf-moss” was discovered; the white alder furnished the various shades of the orange color; after a while weavers began to scrape off the soot from the timber support over the fireplace, which furnished the black, and by diluting or mixing this with some other color furnished the various shades of brown; blueberry had long suggested itself in coloring the basket in various shades of purple. If you can imagine yourself in the place of the basket maker, you can keep on adding to the things from which she drew her scheme in coloring. After all, to dye straw is not such a profound secret as some imagine.

Use and Names of Baskets.—Wood was always at the command of the Tlingit people, and a wooden box was much easier to make than a woven basket for the purposes of cooking by boiling and of carrying water. Only among a plain sort of people and the uneducated was one utensil used for many purposes. In nearly all families there was a variety of utensils, devised to accommodate the various purposes. But when away from the permanent homes there were an infinite number of ways in which the root basket lent its services.

The basket forms took their names either from their uses or from their shapes. Few examples are here illustrated, and owing to the limited space some of the types have to be given only by brief descriptions:

Qäku’-tahyi’, “basket-lower half,” is a basket made for the purpose of cooking foods by boiling. As its name implies, it appears like a common cylinder with the upper half cut off. The heavy root strands used make its body much stiffer than that of an ordinary kind, and its border is greater in diameter than its foot, which makes it flare like a tin dishpan. The reason for this is that when the basket is placed in the hole dug in the ground for it, the sides, which become yielding when exposed to the intense steam, are held up between the surrounding earth and the weight of the contained liquid and since the steamed sides have a tendency to fall toward the liquid, they must in this case lean toward the solid earth.

It must not be supposed that the basketry cooking pots were placed over a fire, as those of a metal. As I have already said, a hole was dug in the ground, and in this the cooking basket was placed, about one third of its height standing out above the level of the ground so that no dust or sticks should fall into the cooking. This projecting part was supported by four stakes, each of which, at an equal distance apart, was driven down against the outside wall, with its upper end fastened to the border of the vessel. After the pot had been thus secured against accident, the food and water were placed in-it, and with a pair of wooden tongs the stones which had been heated were dropped into the cooking.

Tähl’, “flatten,” is illustrated in Fig. 49. This shape was made to be used in berry picking, especially the huckleberry, which grows as if it had been spilled or scattered all over the field, and to pick it one at a time would be a tedious job indeed, so the problem of the quickest way was solved by the invention of the tähl’. The berries are then put by handfuls, leaves and all, into the flat basket, and after a number of handfuls it was then taken up with both hands, shaken in a whirling motion, the contents bounced up and down, and blown on at the same time, thus driving off the leaves, and the sticks were removed before the berries were emptied into the all around cylindrical type called chewkaet (Fig. 50). The name chewkaet means “always at the side” of the picker, and it was not allowed to stand at a certain point, as in other kinds of berry picking, since Madam Bear herself was sometimes out for the same kind of berries, and whenever she came upon a basketful it was a “help yourself” with her.

Museum Object Number: NA9218

Image Number: 12592

The huckleberry picking at Chilkat, was attended with a spirit of fun making; hence, no young person was compelled to join a party going to the berry mounts, and for this occasion most girls had their tähl’ and chewkaet made with some attractive designs, not only to carry something nice on the picnic, but also to identify their own among many other baskets. The handiest size of the tähl was about fourteen inches in diameter, and the chewkaet held about two pecks.

Khōt is a term applied to an open work basket, the weave of which is shown by the modem basket illustrated in Fig. 51, but the original shape was something like the lower half of a sailor’s dunnage bag. The khōt was employed in trying out fish oil; it was used also for cooking in a dug out wooden pot. Meats or berries were placed in the khōt, and dipped into the water that had been boiling in the pot. The largest of this type has a capacity of about one bushel.

Qäku’-khisha (drinking basket) is a term applied to a small cylindrical basket, almost the same in size and shape as a pint condensed milk can.

Since a normal person is able to put his lips to an open stream of water, there was no great need of a drinking cup, but during the days when the custom of lustration had to be observed, even the stomach was cleared in the purificatory ceremony; to do this, salt sea water was used, for its emetical quality, which was usually taken in seclusion, and for this purpose a small wooden box was provided, but in the possession of the ever shifting class of hunting families the drinking basket was occasionally seen.

Wushto-qa’gu (one within another) is a small cylindrical case, made in two pieces, one sliding within the other like a telescope. The average size of this type is about three inches in diameter for the outer piece, and about four inches in length for each. Formerly this type was made for use as a case for charms or magical medicines, and has been more particularly the property of the shaman, which accounts for the extra fineness of workmanship seen in all those found. Wushto-qa’gu is said to have been the first type made, in Chilkat, with a design; but the embroidery on this first one was worked with split quills of eagle feathers. So this must have been long before the shock’ was introduced among the group.

Although the root basket, in Chilkat, has always served well in many ways, the thought of its use came mainly with berry picking, which was one of the important industries in the locality. After the products of the summer season had been laid in store for the winter, the principal one among those gathered during the autumn was kawhueh’, a red, juicy berry which is sometimes called “high bush cranberry.”

Museum Object Number: NA7638

Image Number: 12642

There were quantities of the kawhueh’ to be found almost anywhere along the Chilkat River, but some picking grounds were handier than others. These were not far from the villages and some were along lakes, while the others were along swift streams and hilly places which were not so easy to get to. Hence, in order to give everybody an equal chance to an easy time, a day was announced by the “townsmen” (town council) for what was termed “pickers’ stampede,” and until that day no one was allowed to go for the berries.

When it came to the provision with regards to the maintenance of life there was no exception made in the rules which governed the economic life in Chilkat: the nobleman, the townsman, the rich, and the poor enjoyed equal rights, but it also became necessary to adopt rules which protected these rights. Near the day of the pickers’ stampede slaves were stationed to guard the best picking grounds against a greedy or selfish person, who would sometimes steal ahead regardless of the rules; if any violator was caught picking there, before the day set for all, he never escaped his punishment at the hands of the authorized guards, which was, sometimes, besides losing all that he had picked, to have his canoe destroyed.

A day before the pickers’ stampede families from the neighboring villages began to arrive at Kluckwan, the principal town in Chilkat, which was always the starting point on the occasion. It was the day on which all baskets were brought out and unfolded, and their pack straps adjusted, as were other camp equipments, and everything was fixed in readiness for an immediate start.

It was not every Tlingit who fared well on the kawhueh’, in fact there were many who would not eat the berries in any style, but the excitement of the pickers’ stampede caused enough thrill to arouse even an indolent person to move lively and to mix up in the rush of the start. The occasion inspired them somewhat as the white man’s patriotic celebration does him, one joined whether or not it benefited him.

At dawn of the set day, one was roused from a happy dream by a confusion of noises: there were sounds of moving things; there was laughter; shouting and yelling at some delayed person to move lively; all in chorus with the howling and yelping of many dogs that were about to plunge in to swim across the river after their masters’ canoes. It was the pickers’ stampede which came only once in a year, so no one should entertain a feeling of disgust at anything. Would this day be comparable to that of the out door sports or the field day of modern times? Nay, the thrill of the sports are felt only by the young and sometimes rich, and it is usually a thing of the past with a matured person, and some persons cannot always afford to participate. But on the day of the pickers’ stampede, there was no exception, young and old, rich and poor for once felt alike, and dignity and pride were for the moment forgotten. There was never a healthy being left behind in Kluckwan, save the mangy dog which was always fool enough to chase after the wandering echoes of his own howls, from one deserted house to another.

When once started anyone might go as fast as he liked, and it was the slow man’s own fault that he arrived to take what was left. There was, however, always ample space in all the fields, but the easiest grounds were the first taken, and no reservation of grounds was recognized. Only to show respect to the noble families of limited means, who were usually the last to arrive on the berry fields, some best places were left alone. As for the aged persons, there were always many young men to volunteer their free services to the needy.

A set of three sizes of baskets was made for use in this kind of berry industry. The first, called segä-tä’na, “neck-carrier,” was suspended with a cord around the neck, and hung against the chest of the picker; into it berries from the bushes were thrown. It was the smallest of the set, with a capacity of about two quarts.

The second, called yä’nah, “packer,” was carried around on the back by means of a single packstrap which encircled the shoulders, with both ends secured to the two loops supplied on the border. Into the yä’nah the segätä’na was recurrently emptied. It was medium in size, with a capacity of about one peck.

The third was called qä’ku (an old term, the definition of which is unknown, applied to baskets in general) or was sometimes called tāh-ton’, “bottom-rest” (stationary). This was the largest of the set, with a capacity of about two bushels, the measure which equals a little over one hundred pounds in weight. The pliable, yielding walls of this size required a support in some manner to hold the whole from settling toward the foot, to comply with this the body was expanded in the middle of the height; thus the belly shape. So when the basket was full the reduced circle of the border was held up by the loose load itself. Tähton’ was a term derived from the method of placing the burden basket at a convenient point on the berry track, so that a number of pickers might empty into it. Each picker, then, carried around the segätä’na and yä’na, and when these had been filled they were emptied into the qä’ku. When the qa’ku in turn had been filled a man packer came along and carried it into camp or to the canoe landing, informing the pickers of the location of an empty one.

The kawhueh’ picking was all done in two days at the most. There were about four qäku-measures picked to each adult, and some families were usually satisfied with a ten qäku load. There are a number of interesting methods to be described in the kawhueh’ industry, but we will have to conclude with some idea of the former chief purposes of the Chilkat people with the basket, And we could go on for many more pages, describing types that have, from time to time, appeared since the Tlingit basketry came into modern trade, but we can make only a few more remarks about those we should not leave out.

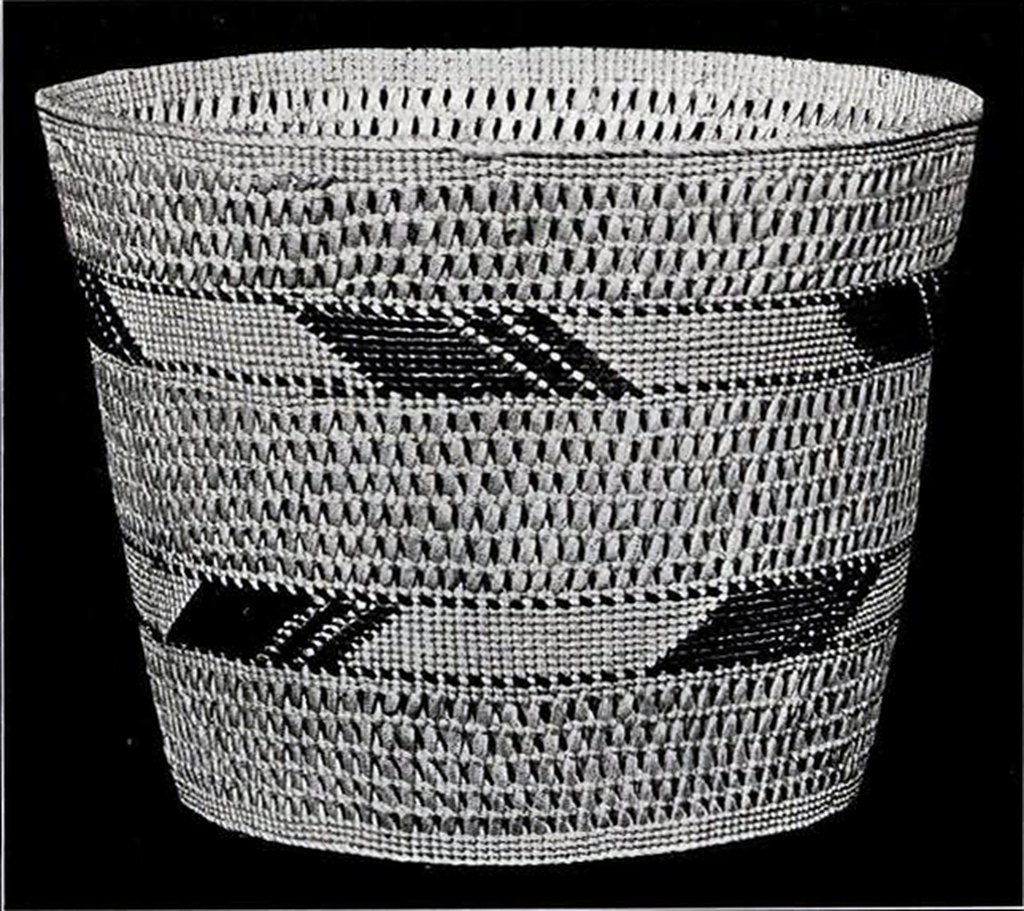

Among the finest specimens in the large collection of the Tlingit baskets, placed on exhibition in the North American Indian basket room, in the University Museum, is a medium sized basket of recent make (Fig. 52). The crosslike designs on the two outer bands are the variations of what they called the “shadow of raven’s tail,” while on the middle band is embroidered another old design called “incline, or mountain-side vine.” There was never any question about these, but the curved in outline of the walls caused question by some authorities on the art of North American Indian basketry. There seems to be some doubt about this type being an old one, but, from its native name, sähu-shäki’yi, “hat-crown,” it must be old. True enough, it is one of the most difficult forms to make among the Tlingit baskets, but the reducing of the middle part of its height is not a new invention as can be seen by comparing this with the crown part of the old rain hat illustrated in Fig. 53.

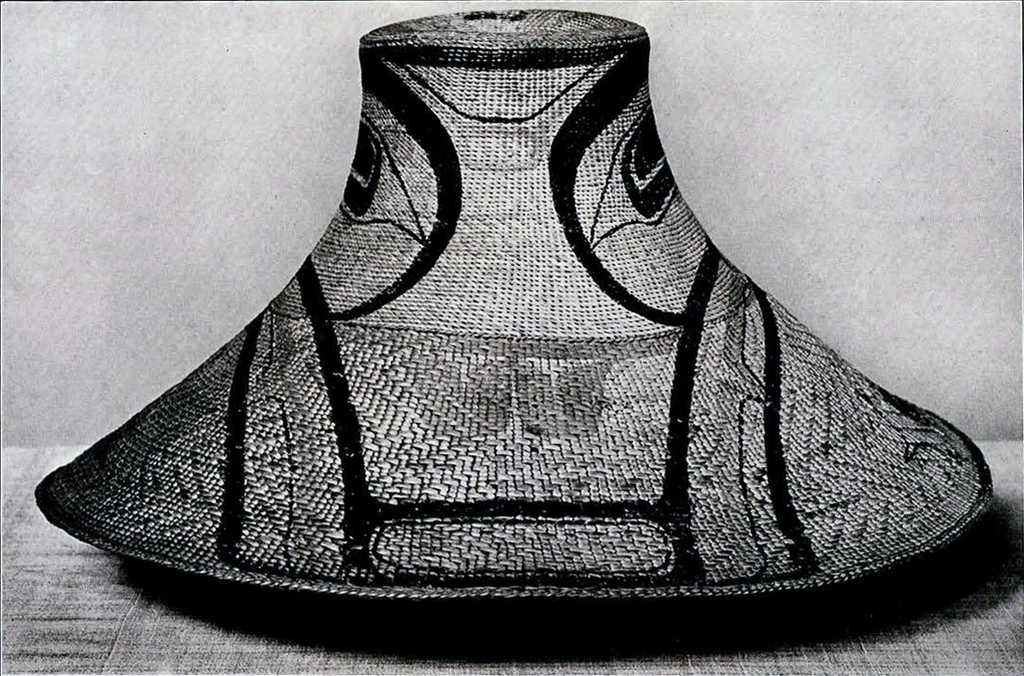

The rain hat is one of the samples of the old time basketry; the form is said to be an invention of the Haida speaking people, who inhabit the Queen Charlotte Archipelago. The brim part was usually covered with the intricate, self colored patterns which appeared like zigzag lines in relief. This same pattern was woven on the border band of some of the burden baskets. The totemic symbolism which is seen on some was never embroidered, but painted on, as on the specimen shown.

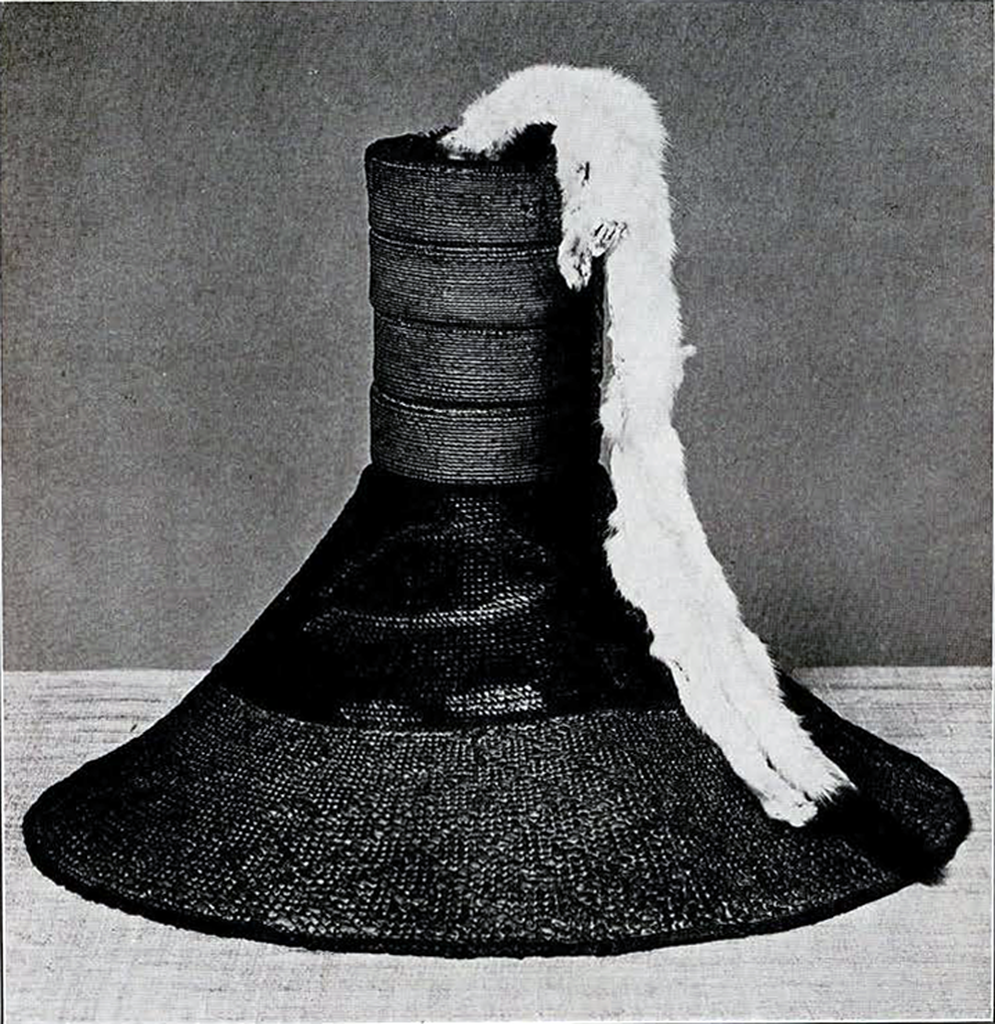

Shädäh-koohu’, “headcover stock” (headcover with stock), is a term applied to the old ceremonial hats, one of which is here illustrated (Fig. 54). The name is derived from the cylindrical ornamentation rising from the top of the crown. This “top stock” form is the masterpiece in execution and ornamental weaving; its complicated formation is a lost art to the weavers. There now may be an expert basket maker who is possessed of sufficient skill to copy the top stock, but no attempt has been made to reproduce it. The flexible ornamentation of the hat illustrated is woven like a cylindrical case of four circular boxes, connected in intervals, each by a constricted tubelike opening, and it can expand and contract like an elastic band. Shädäh-koohu’ was the first object in basketry which was mentioned in Tlingit mythology, and the workmanship on it justifies its claim to the origin of the art in spruce root.

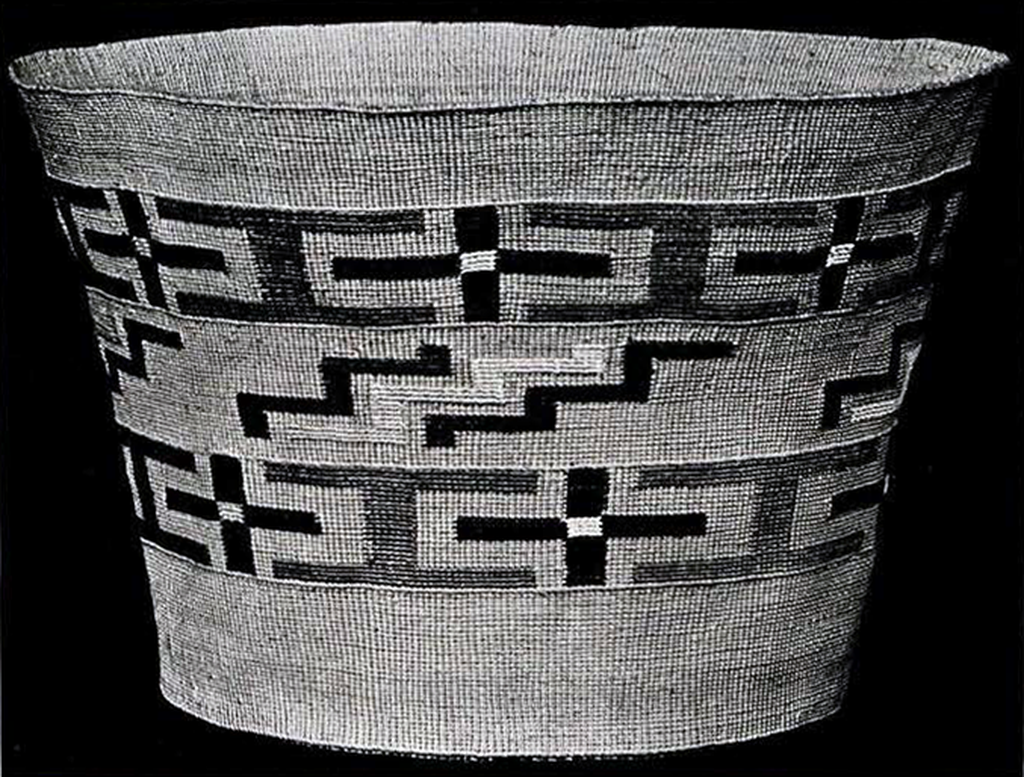

Before I stop, let us go back to the old “Rest-in-shadow.” I call the old basket which is illustrated in Plate VI by this name because I am almost certain it is the same one which, at one time, was transferred along with other classes of property, by one of the clans of Hlähäyik’ to its rival party, at war, of Chilkat, as an indemnity. The basket afterwards was often referred to at Chilkat in a manner of ridicule, because with them all root baskets were made for use in berry picking, and a mere utensil bearing a personified name, was ridiculous. Hence, at its new home, Rest-in-shadow was disgracefully thrown in among other common burden baskets, and after many years of hard service it was given to a Whoozdä-quan’ trader in exchange for two sacks of potatoes. This was the last thing I remembered hearing about it.

As I look at and study the old basket which has come through so many changes of life, it seems to me that it has indeed reached its final stage of service, but the idea of the maker can still be seen through the veil of age. Every item of form, color and design of this old specimen has in it the true element of native art. The designs: on the two broad bands, between the sidewise series of the shark’s teeth patterns, are two vertical lines of solid brown, each pair on the natural straw background, representing shadows of two standing trees, by which, obviously, the name of the basket was shown. On the narrow middle band are the tracks of a fortune hunter, who searched here and there, from side to side along his trail. And the crosslike patterns, at equal distances near the foot, are a design representing the shadow of raven’s tail; while the body of zigzag lines placed in between, represents the current of a stream of water. Only the maker’s people knew the meaning of this combination of patterns.

From what we have heard about it the old Rest-in-shadow was created in glory and was offered with pride, but in the land where higher art prevailed it became a slave. After years of hard life it drooped into pensive sadness, and, like many others of its kind, in the vale of melancholy, its last service to humanity was to have been to support the cradle of the new born, thence to its rest in some abandoned burrow. But the hand of the white man invaded the precincts of “savage” life in time to rescue it from its last humble service, and to place it in a position worthy its beauty.

L. S.