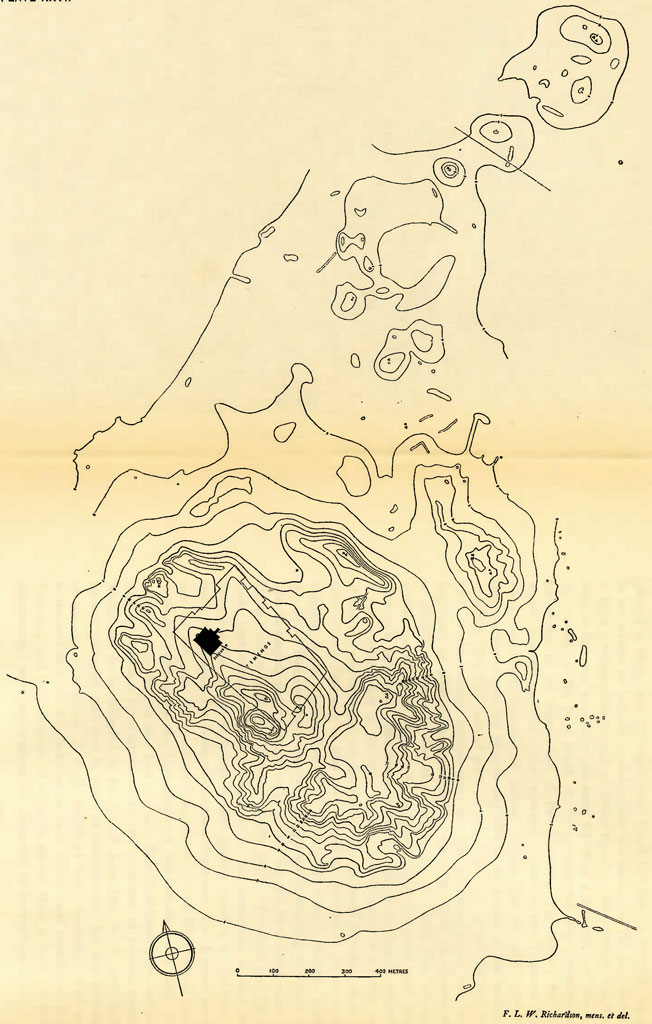

THE tenth season of the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and of the University Museum, Philadelphia, began work in the field on November 25, 1931, and closed down on March 19, 1932. My staff included, in addition to my wife, Mr. J. C. Rose, who came out as architect for his second season, and Mr. R. P. Ross-Williamson, who acted as general archaeological assistant; Mr. F. L. W. Richardson of Boston, Massachusetts, was also attached to the Expedition to make a contoured survey of the site [Plate XXVII]. No epigraphist was engaged, for the work contemplated was not likely to produce much in the way of inscriptions; but an arrangement was made whereby Dr. Cyrus B. Gordon, epigraphist on the Tell Billa Expedition of the University Museum, could be called upon to give his services if and when required; actually a single visit enabled him to do all that was essential. To each of these I am very much indebted. As usual, Hamoudi was head foreman, with his sons Yahia, Ibrahim and Alawi acting under him, and as usual was invaluable; Yahia also was responsible for all the photographic work of the season. The average number of men employed was 180. This relatively small number of workmen, and the shortness of the season, were dictated partly by reasons of finance but more by the nature of our programme which envisaged not any new departure in excavation but the clearing up of various points still in doubt and the further probing of sites already excavated, with a view to the final publication of the results of former seasons; the work was therefore rather scattered, five different areas being investigated in turn.

In the published plans of the Temenos (Museum Journal, XXI, 2, Plates I-IV; Antiquaries Journal, X, Plates XXIX-XXXII) it will be observed that immediately inside the ‘Cyrus’ Gate on the northeast side there is a large area in which no buildings at all are shown. The ground surface here has been much denuded by water action and the probability of any buildings of the historic periods surviving had seemed so slight that for eight years I had left the site severely alone. In the winter of 1929-30 a trial trench cut just inside the gate brought to light a bitumen-lined tank of Third Dynasty construction. Unpromising as the area was, there did seem therefore a possibility of recovering enough to fill in a blank in the ground-plan and complete our knowledge of the topography of the Temenos. This season the trial trench was enlarged in every direction. Close to the Temenos Wall there were found remains of various periods, but the walls were too fragmentary to give any plan or any idea of the nature of the buildings of which they had formed part. A very little way inland the last vestiges of the historic periods gave out and we encountered only wall fragments of plano-convex mud bricks, these also quite incoherent and so shoddy in character that the mean houses to which they belonged would scarcely have been worth excavating even had they been tolerably well preserved. Our results here were therefore largely negative. It was evident that in the time of the First Dynasty of Ur this part of the site was occupied not by temples but by small private houses; if there was a Temenos at that date it did not extend so far from the Ziggurat as the ‘Cyrus’ Gate of the Neo-Babylonian enclosure. Under the Third Dynasty there was here an important building to which the tank belonged, and a second (apparently, like the first, constructed by Dungi) whose southwest front lay inside the late Temenos line but its main part extended beyond that line to the northeast; at that date therefore the official buildings in this quarter stood in no relation to the limits chosen for Nebuchadnezzar’s Temenos. The Kassite period saw the site once more occupied by private houses the ruins of which extended right under the foundations of Nebuchadnezzar’s wall. The conclusion is that, in this part at least, Nebuchadnezzar’s ground-plan was not dictated by tradition or by the existence of ancient temples which had to be included in his Sacred Area, but, in all probability, he was enlarging that area in order to provide room for new buildings of his own foundation. A single length of heavy mud-brick wall with buttressed face, of Neo-Babylonian date, which runs parallel with the Temenos wall at a distance of eighteen meters from it, may be Nebuchadnezzar’s work and explain the alignment of his enclosure.

In the First Dynasty ruins there were found a few clay tablets and jar-sealings, but otherwise the site was barren of objects.

The Cemetery Site

At the close of the season 1928-29, there was found at the northeast limit of the predynastic cemetery a grave, PG/1422, which in my report (Antiquaries Journal, IX, page 307) I described as apparently of intermediate date inasmuch as its contents combined the characters of the earlier and of the Sargonid periods. In the season 1929-30 there were found in the immediate neighbourhood of this grave two pits (PG/1846-7) which had been plundered in the time of the Third Dynasty of Ur but retained untouched certain subsidiary burials whose furniture was also of mixed character. In all of them the pottery was that found in graves dated by inscriptions and so forth, to the Sargonid Age. The cylinder seals were not quite Sargonid in type but manifestly later than the First Dynasty of Ur; the jewellery was for the most part late, but a gold figurine in PG/1422 recalled rather the style of the early graves, and some of the weapons were cast, and of the types found in the Royal cemetery, but there were examples of the hammered copper weapons which by the Sargonid time had replaced bronze castings. A careful analysis of all the graves in the cemetery area, worked out in the summer of 1931, confirmed first impressions. It became clear that on the northeast outskirts of the old cemetery there was a homogeneous group of graves which, while coming very close to the Sargonid in date, were yet definitely earlier than Sargon; moreover they presented certain unusual features, in that PG/1422 was very much richer than any other late grave found, and PG/1846 and 7 were large rectangular shafts each containing a number of graves arranged round their sides (the middle of the shaft, presumably the place of the principal burial, had been plundered) so that they bore some resemblance to the royal graves, for example PG/1054. It seemed to me tolerably certain that we had here interments of the time of the Second Dynasty of Ur, possible that they were royal graves. The presence of subsidiary burials gave colour to the latter view, the doubt as to the date of the Second Dynasty and the probability that it preceded the Sargonid age by a relatively short space of time supported the former. That the graves were not of the First Dynasty of Ur was shown by the seals and by the pottery, for the types known to be characteristic of that dynasty were conspicuously lacking here, and some at least of the Sargonid types found had not been introduced, so far as we know, under the First Dynasty. More evidence was required however. The area in which further graves of this group could be found was limited, for the great mausoleum of Dungi and Bur-Sin, lying just to the northeast of those already excavated, had destroyed all earlier remains down to the Jem-det Nasr level, but between the mausoleum and the excavations of former seasons there was a strip of ground not yet touched, and it was accordingly marked down for clearance this winter.

Image Number: 191962

Image Number: 191966

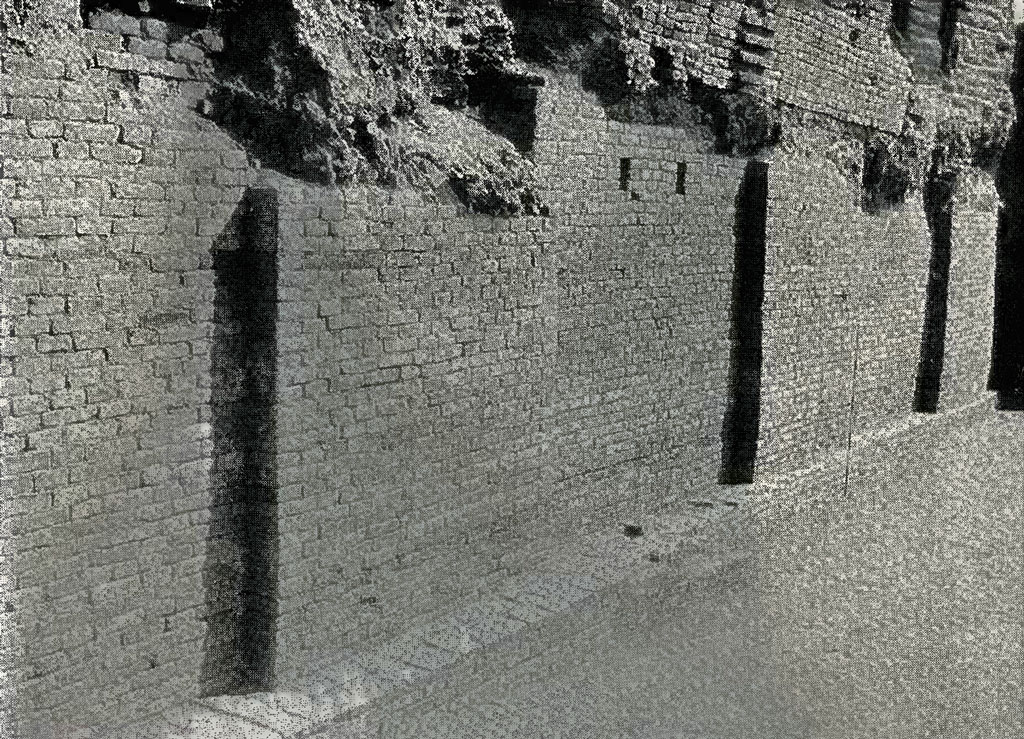

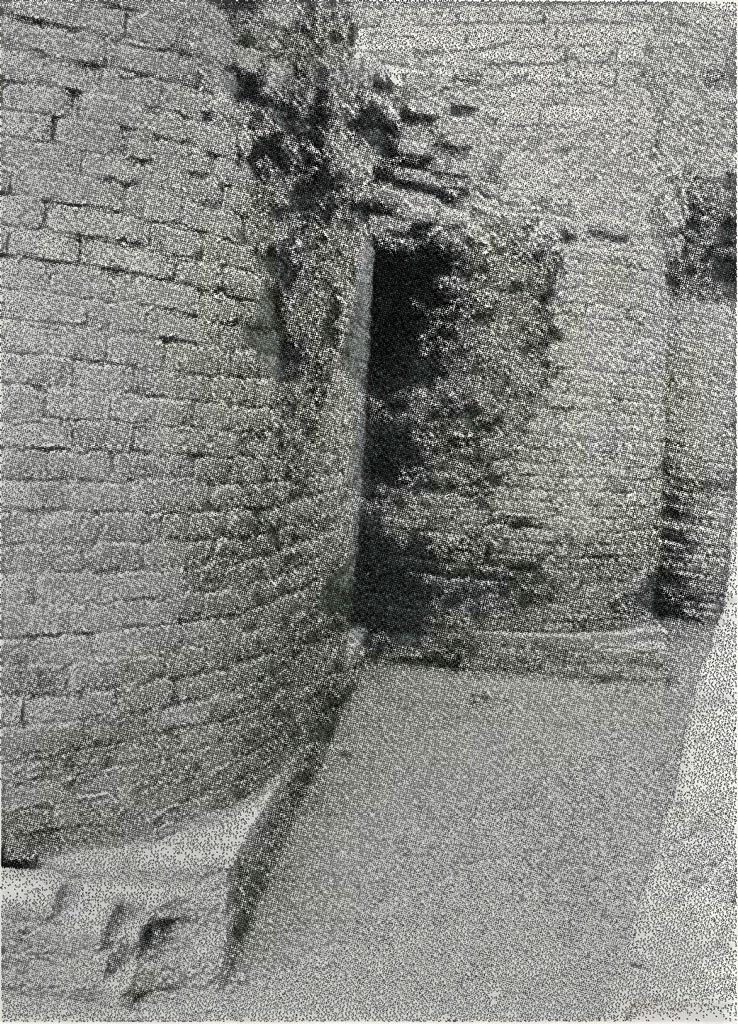

The first result of our work was to expose to ground level the outer (southwest) wall of the mausoleum [Plate XXVIII, 1]. This splendid example of Third Dynasty brickwork ranks second only to the Ziggurat in quality and in preservation. Like the Ziggurat, the wall is laid out not in a straight line but in a slight convex curve, and the buttressed wall-face also is not only battered but convex vertically; the most striking feature is at the south end where the two rounded corners resting on square bases are really magnificent [Plate XXIX, 1]. Each of these corners had been breached, in each case to exactly the same height above the foundation, presumably by robbers in search of foundation-deposits; the only other corner of the building which survives (the west corner) was excavated by us, a shaft being driven down into the brickwork from above to below the foundation of the super-structure, but no foundation-deposit was discovered; whether the old robbers had any better luck it is impossible to say.

The Dungi mausoleum originally stood in a hollow, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say on a terrace cut into the slope of the old cemetery site; the top two courses of its foundation offset were exposed, but from the wall the ground level sloped up steeply to the high ground on the southwest. On the slope close to the wall we found some two hundred bricks either stamped with the Dungi stamp or bearing the finger-prints which his brick-makers favoured. They were stacked in regular rows, leaning one against the other, three and four deep, and obviously had been put here for use in the building but left because they were superfluous to it. It is a curious commentary on the amenities of the Third Dynasty city that a pile of waste bricks should have been let lie in the proximity of one of the most important buildings until they were covered by rubbish. Under the bricks we found a very large number of inscribed tablets, (apparently business documents, but they have not yet been read) which had been spread over a piece of matting and then the bricks had been stacked above them.

Image Number: 192059

Image Number: 191965

The level at which graves could first be detected, that is the level of the tops of their shafts, was virtually that of the Third Dynasty ground-level against the Dungi mausoleum, but here the slope of the ground has to be taken into account; in the time of Dungi more than three meters of deposit lay above the shafts, and since the workmen who cleared the ground for the building cut it back at a slope, they failed to discover them. Bur-Sin’s workmen found and plundered PG/1846 and 7—bricks stamped with the king’s name and quantities of bitumen, were found by us deep in the shafts—because Bur-Sin’s annex projected to the southwest and encroached on the cemetery area, but though the vault foundations cut into the side of PG/1848, the workmen failed to detect its presence and left it otherwise undisturbed. The terrace cut back into the hill for the northwest annex of Bur-Sin lay so much higher than that of Dungi that the oversight is easily explained.

Image Number: 192083

We discovered and cleared two shafts and part of a third. PG/1848 and PG/1849 (the partially cleared shaft) lie to the northwest of PG/1847, which was dug in 1929-30; PG/1850 lies to the southeast of PG/1846. All the shafts lie in a row, and their southwest sides are in absolute alignment; they are separated from each other only by narrow walls of unexcavated soil; they should therefore be almost contemporary; at any rate there must have been some mark above-ground which defined exactly their position and enabled the grave-diggers to keep their line true and to avoid disturbing the next grave. From the point of view of chronology, which was the main interest of our excavation, the fact of prime importance was the following:—A wall of mud-brick ran from northwest to southeast above the southwest edge of the line of shafts. At the northwest end, by PG/1848 and PG/1849, we failed to trace it, but there were remains of it over PG/1847 and at the south-east end of the excavated area it was standing to a height of 2.25 meters. It was 2.40 meters wide at the base, diminishing to 1.50 meters, and was built partly on the firm soil into which the shafts had been sunk, but for nearly half its width it rested on the filling of those shafts, and it also overhung the pit at the bottom of which was the grave PG/1422. A branch wall ran out from it along the southeast edge of PG/1850, likewise resting half on the grave-filling and half on the solid ground, and there were traces of a similar branch-wall along the northwest edge of the same grave, although these were so scanty that without the other walls they could scarcely have been taken as evidence. Possibly the main wall was built to define the new cemetery area; possibly it was, with the branch walls, part of a superstructure common to all the shafts; in any case it can have been built only after the shafts had been dug and filled in again. The mud bricks of which the wall was built were of the plano-convex type, much rounded above, measuring 0.27 x 0.17 meter with a maximum thickness of 0.10 meter. In the foundations of the wall there was found a hollow in which lay piled, one on the top of another, five copper heads of bulls [Plate XXX, 3]. The heads had obviously belonged either to statues of animals or to furniture; either, that is, to reliefs or figures in the round such as decorated the facade of the First Dynasty temple at al ‘Ubaid, or to such things as the harps found in the ‘old cemetery’; but they had been broken off from whatever it was to which they had belonged and had been deposited in the wall foundation as fragments. It is natural therefore to assume that they were older than the wall itself. Now in point of style the heads closely resemble those of al ‘Ubaid, and contrast strongly with the many animal heads from the old cemetery; they have all the formed conventions of First Dynasty art and have altogether lost the naturalism of the predynastic sculptures; it is impossible to mistake their parentage. We have no means yet of knowing how long the First Dynasty canons persisted; the heads might be considerably later than A-an-ni-pad-da, but they cannot be much earlier; fortunately as evidence for date they are superfluous.

Image Number: 191979

Museum Object Number: 32-40-226

Image Number: 191978

The existence of the plano-convex wall over the top of the shafts and the presence in the shaft PG/1848 of both rectangular and plano-convex bricks (see below the detailed description of the shaft) prove that the graves date from the moment of transition from the plano-convex period to that in which square bricks were used for building.

At Tello it has been proved that plano-convex bricks were employed until the reign of Entemena and then went out of fashion. It is reasonable to suppose that the change took place at more or less the same time throughout Sumer, at least within the margin of a century or so; and though at Ur no definite evidence has been forthcoming we can fairly say that our plano-convex wall and the shaft graves beneath it are not later than Entemena.1 One recognised system of dating would make Entemena come about 2800 B.C., he being the fifth descendant of Ur-Nina, who is put at between 3000 and 2900 B.C.2 This would seem to be too early a date for our shaft graves.

The general resemblance between the contents of the shaft graves and those of dated Sargonid graves in the matter of headdress, most of the pottery,3 and many of the metal types, favours a reasonably close connection in time, something much shorter than the three or four centuries implied by the early dating of Entemena. On the other hand, certain noticeable differences, for example, in the cylinder seals, and in some metal types, and the survival of predynastic axe forms, and the use of plano-convex bricks in the graves as contrasted with their complete disappearance by the time of Sargon, necessitate a real time gap between them and, therefore, between Sargon and Entemena. This is against Weidner and Christian and would agree with Sidney Smith’s chronology, bringing Entemena down to about 2600 B.C. Again the marked difference between the furniture of the shaft graves and the pottery and cylinder seals of the First Dynasty of Ur must mean that that dynasty is considerably earlier than the graves and, therefore, than Entemena; it is entirely opposed to that manipulation of the King-lists by which Weidner and Christian make the First Dynasty and Ur-Nina contemporary, and supports Sidney Smith’s contention. The yet more marked contrast between the shaft graves and those of the Royal Cemetery puts out of court the theory of Weidner and Christian that the Royal Cemetery should be dated to the First and Second Dynasties of Ur.4

Admitting that the relative date for the shaft graves is established—that they are not later than Entemena and might be contemporary with any one of the Lagash rulers preceding him—is there any excuse for the further assumption that they represent the Second Dynasty? That there should exist at Ur graves of the Lagash period is inevitable; but is there anything to connect them with a particular dynasty of kings of Ur whose names do not occur in them and .whose date is admittedly unknown? Their position in the time sequence, between the First Dynasty and Sargon, is compatible with whatever exact date be assigned to the Second Dynasty, but that is clearly not enough.

I have remarked that PG/1422 was unusually rich; indeed, for its wealth of gold and other objects it stood out from the general run of late (Sargonid) graves almost as conspicuously as did that of Mes-kalam-dug from the private graves of the early Royal Cemetery. It was also very much richer than any one burial in the graves PG/1846-50, but these were distinguished from it in another way just as the royal tombs of the old cemetery were distinguished from Mes-kalam-dug’s grave. PG/1422 was a plain pit containing a single burial, the body placed in a wooden coffin, the objects put some with the body and some in the pit outside the coffin. PG/1846-50 were large shafts containing a number of bodies, buried separately and generally in coffins (some were wrapped in matting) but buried all at the same time and with elaborate and long drawn-out ceremonies. No such multiple burials occur amongst the private graves of the old cemetery, nothing like them is found in the Sargonid graveyard; but the analogy with the old royal tombs is striking. But though most of the bodies are adequately adorned with gold, the ornaments are very uniform; the principal burials, denoted as such by their position, are but little richer than the rest, and there is none of the violent contrast that distinguished the occupant of a royal tomb-chamber from his followers in the death-pit. If these are royal graves, they are the graves of very minor royalties; and, while it is of course possible that the kings of the Second Dynasty were no more than that, I am far from claiming that these are their graves. It might be argued that they are ‘death-pits’ belonging to tombs placed elsewhere,5 possibly even above the top of the shaft; it is difficult not to push the obvious analogy with the royal tombs of older date. The closest parallel is with the royal tomb PG/10546 where the shaft was filled in by degrees and the upper burials are individually complete, as here, though in PG/1054 the tomb-chamber was at the bottom of the pit. The most moderate statement would perhaps be this: we have here graves rich, but not so rich as to be necessarily royal, of a quite abnormal type, a partial parallel to which is only found in connection with kings’ tombs of a much older date, and they belong to a period which may well coincide with that during which there were again kings at Ur; to connect them with the reign of those kings may explain their peculiarities; to attribute them to any other period (which would be no less arbitrary) would make them inexplicable.

Image Number: 191969

Image Number: 191972

In any case we have one important historical result. These shaft-graves, dating as they do before the close of the ‘plano-convex’ period and being demonstrably not of the First Dynasty, prove that it was the Second and not the First Dynasty of Ur that was overthrown by Ean-natum of Lagash. Of the Lagash domination the excavations have produced evidence enough, but there have been no names on the Ur side to correlate its rulers with those of Lagash, and it was open to suggest that Eannatum destroyed the First Dynasty and that the shadowy Second Dynasty must be interpolated between the earlier dynasty of Eannatum and the rule of the later patesis Ur-Bau and Gudea; that is now shown to be impossible. It is satisfactory that the conclusion so enforced does in a measure support the evidence of the King-lists.

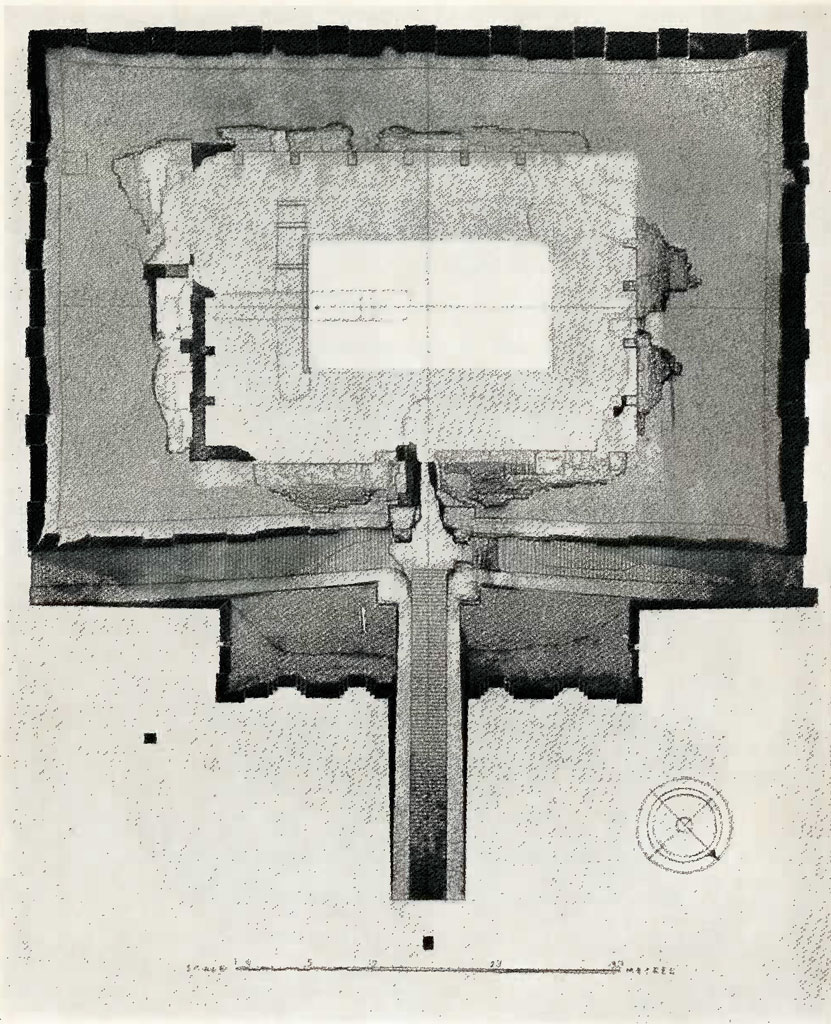

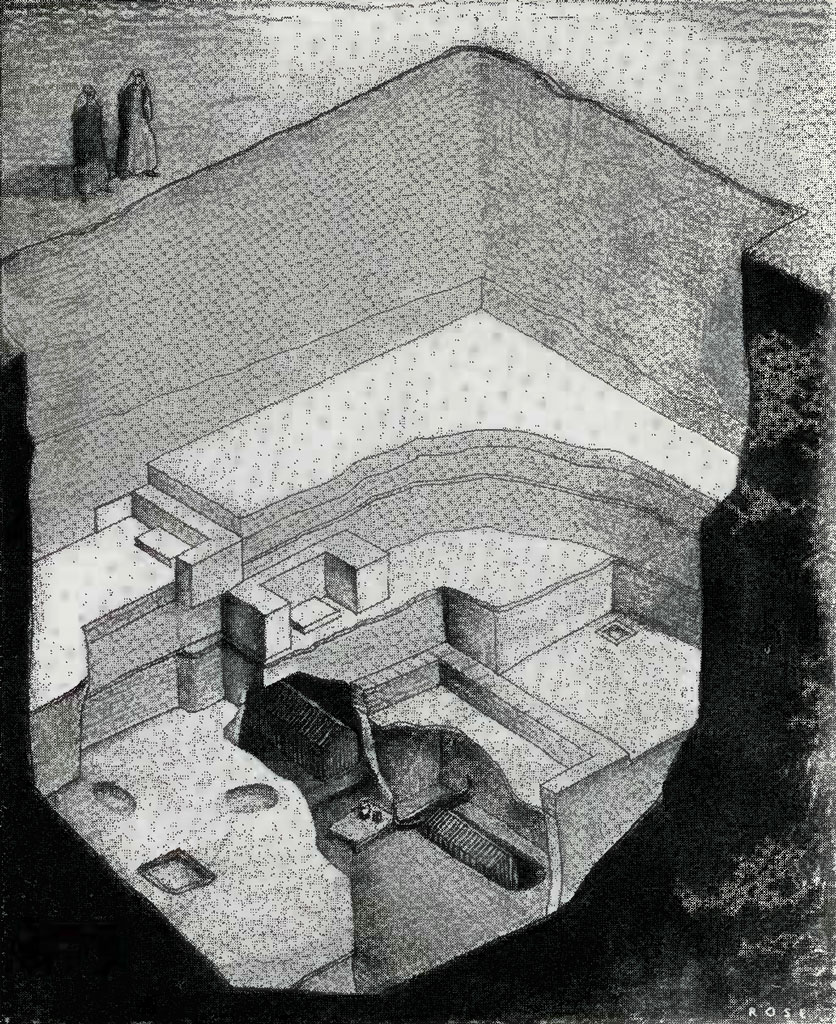

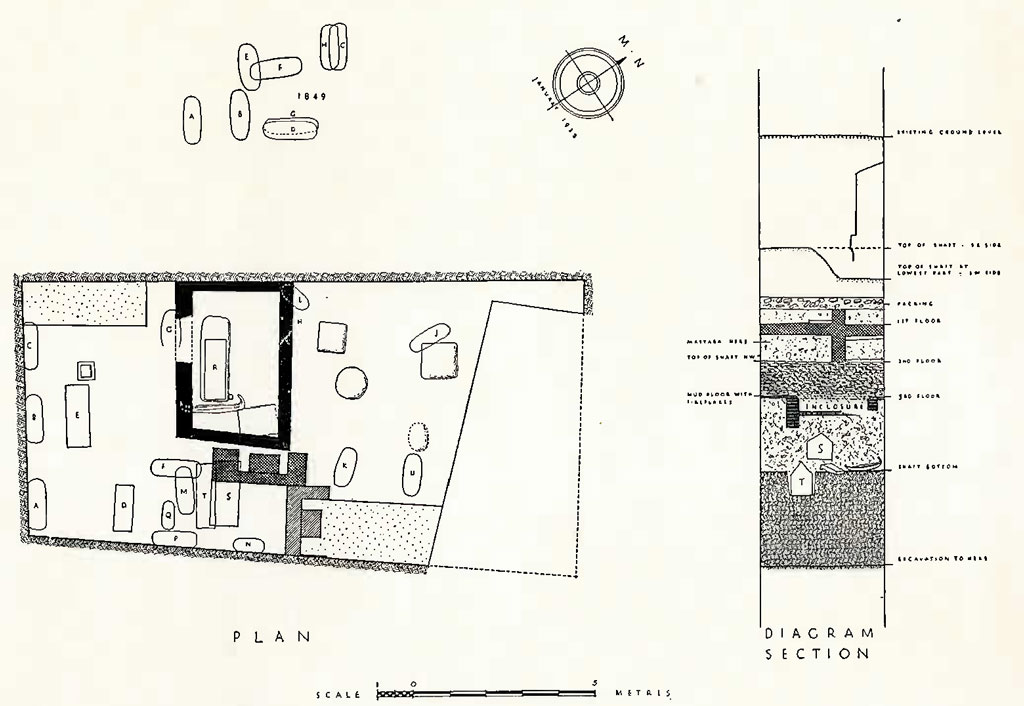

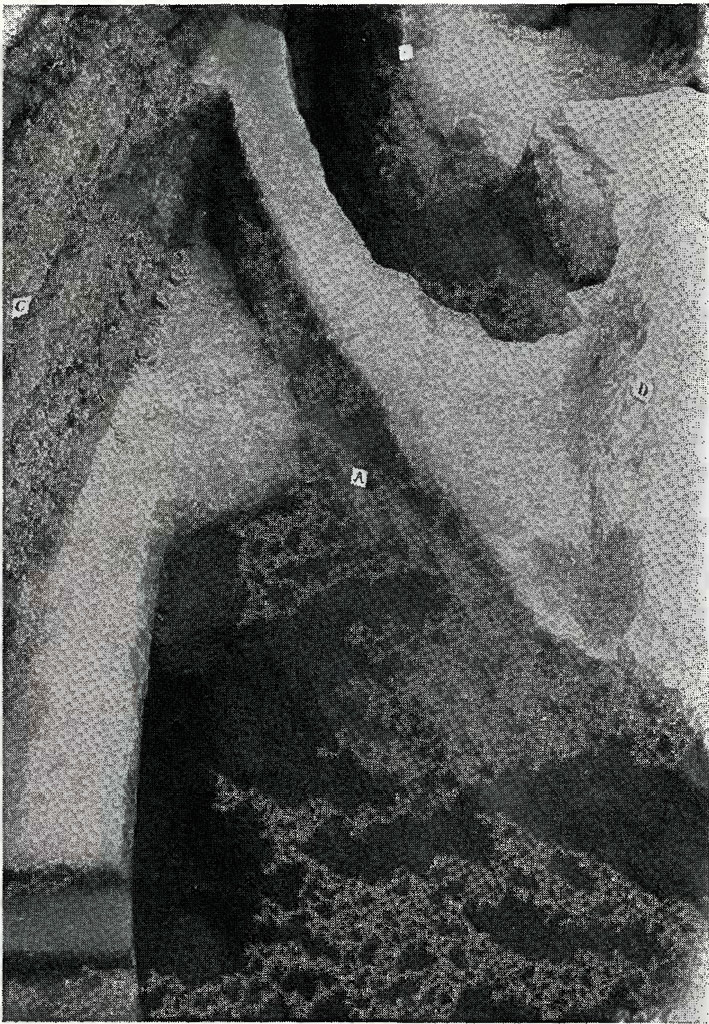

Description of PG/1848 [Figure 1]

The shaft measured 15.30 x 7.50 meters and was fairly rectangular; the angles were oriented to the points of the compass with tolerable accuracy. The top of the shaft was first discernible at a depth of 0.40 meter below the foundation offset of the Bur-Sin mausoleum; the bottom lay at 6.50 meters below that level. The sides of the shaft sloped slightly in from the vertical and were for the most part simply cut in the soil; in places, where the mixed rubbish gave a bad face, they were smoothed with mud plaster.

The southeast wall was preserved to a greater height than the northwest, where denudation had been more serious. Inside the shaft there was a top filling of rubbish containing a great deal of broken pottery, which at the southeast was 1.40 meters thick and sloped slightly so that at the northwest it had a thickness of 2.10 meters. The pottery was not of a very decisive nature, but contained examples which would seem to be more characteristic of the Third Dynasty of Ur than of the Sargonid age, and the impression recorded at the time of digging was that there had been disturbance here, and that the filling was of later date than the shaft itself.

At a depth of 1.40 meters the mixed filling gave place to one of broken mud brick, a packing which extended for 4.00 meters from the southeast side and then broke away and the mixed filling continued, as already said, to a lower level. Below the unbroken mud-brick packing was a wall of mud brick 0.40 meter high and 1.95 meters long; it ran at right angles to the southeast side, and the plastered face of the latter, corresponding to a branch wall, made a niche, in which was a brick altar 0.10 meter high standing on a plastered floor of mud brick 0.30 meter thick. Below this a stratum 0.70 meter thick of mixed rubbish was succeeded by more packing of mud bricks; these, like those of the construction above, were rectangular and measured 0.26 x 0.16 x 0.85 meter. This packing extended unbroken over the whole area of the shaft, and on the surface of it, close to the northwest side, there was found a grey steatite circular stamp seal with a figure of a buffalo and

inscription of the Mohenjo-daro type (U. 17649; Plate XXX, 2). It was difficult to say whether the seal belonged to the floor on which it lay or to the mixed filling which here came right down to that floor level. A shell cylinder seal (U. 17650) and two circular inscribed tablets (U. 17653) were found close to it but more in the rubbish stratum and did not help to date it.

Musuem Object Number: 32-40-437

Image Number: 192085

Image Number: 191988

On the brick floor, in the southeast half of the shaft, there was a second walled niche and altar lying almost under the first but further out into the shaft and oriented at right angles to it; one of the walls of the lower niche had been carried up so that its upper part could be incorporated in the higher niche; this would be evidence that the process of filling in the shaft with successive strata was continuous and done to a definite scheme. In the floor there were several shallow holes either cut simply into the packing or lined with bricks set on edge which contained wood ashes and had clearly been fireplaces.7 From the niche there extended along the southeast side of the shaft a sort of mastaba or bench of brick 2.20 meters long and set back 1.60 meters from the niche front. On the other side of the niche its southwest wall had been widened by a bench, 0.85 meter wide, of earth carefully plastered, standing 0.30 meter high and running back to the side of the shaft.

The brick floor was 1.00 meter thick; below it was a smooth clay floor in which there were fireplaces irregularly placed; one of these was a quite elaborate structure with a bitumen-lined hollow under which was a sort of vent filled with ashes.

Immediately below the clay floor there were encountered the tops of walls of mud brick forming a rectangular enclosure; these walls actually went down for 0.80 meter, but half their height was hidden, and the enclosure was surrounded by a floor lying 0.40 meter below the clay floor with the fireplaces. In the enclosure there were found small animal bones, grain and ashes, and an (early) lapis lazuli cylinder seal (U. 17656) : all probably were remains of some sacrifice; in the floor outside the enclosure there were again fireplaces. The enclosure walls were of plano-convex mud bricks; on the northwest these were sloped and smoothly plastered with mud. In the west corner of the shaft at this level there was a sort of Mastaba standing 0.40 meter above floor level (the walls went down 0.30 meter below the floor) filled with earth and mud-plastered.

All the burials in the pit lay below this last floor; the chief burial was beneath the enclosure, another important burial beneath the altar of the second floor, a third alongside this, and the rest scattered but for the most part in the southwest part of the shaft’s area. They were not all at the same level, but all must have been contemporary in that all lay above the pit’s bottom and below the floor with fireplaces which represents the first stage in the filling of the shaft. In no case was it possible to detect any pit cut from above; the bodies, in coffins or otherwise, seem to have been laid on the filling as this was put in, and therefore it can happen that one is set directly above another (F lay immediately over M).

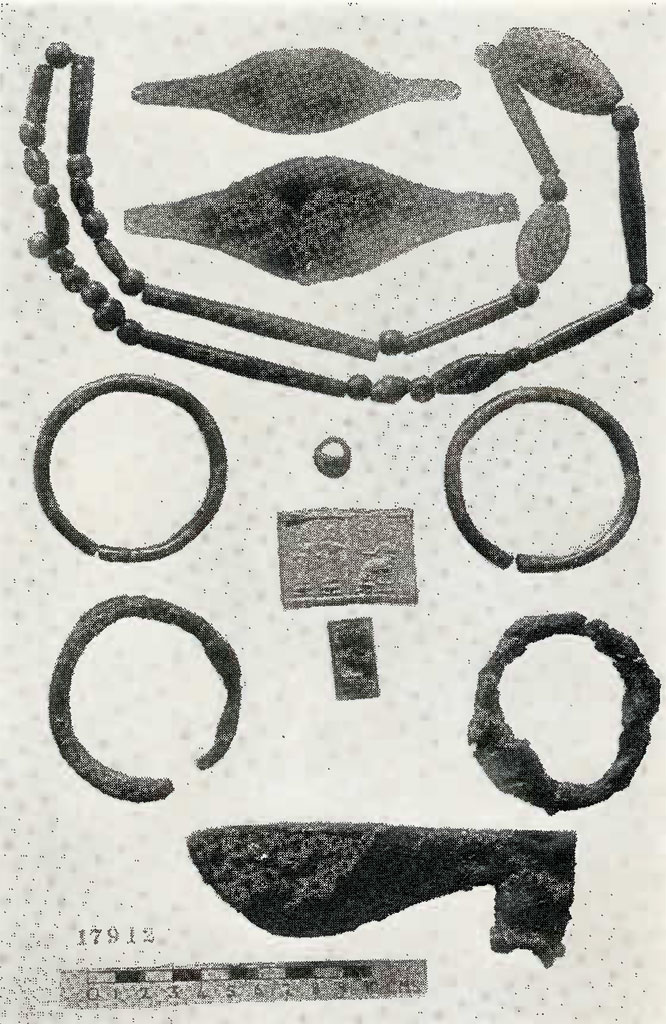

Burial R. Below the enclosure there had been sunk in the bottom of the shaft a roughly rectangular pit large enough to contain a coffin; the pit was lined with matting. The coffin was of wood and measured 1.55 x 0.60 meter; it lay northwest by southeast. In it was a body laid on its right side, the head northwest, the legs slightly flexed, the arms bent and the hands brought across the chest. Behind the legs were the remains of a large copper cauldron; a copper bowl lay in front of the thigh, and by the waist and knees were two examples of a clay vase-type familiar in the Sargonid period. Behind the head was a copper axe—welded, not cast—also of late type. The personal ornaments were four bracelets, two of copper, one silver and one gold; on the head three gold frontlets, ovals of sheet metal, a twisted gold hair-ribbon, two gold hair-rings. Round the neck were two necklaces, one of very small gold and carnelian beads, one of large gold ball beads and very large beads of carnelian, agate and marble (U. 17813).

In the grave but outside the coffin had been set a number of objects; four of these were copper vessels, two of them large cauldrons, a vase and a shallow bowl, all in very bad condition, a copper trident with prongs 0.35 meter long, a copper dagger, and seven clay vessels.

At the foot of the grave was a second shallow depression in the bottom of the pit in which were a bitumen model boat 1.55 meters long and 0.35 meter wide, in or by which were two clay pots, and a sort of table made of reeds over-laid with a coating of smooth clay 1.00 x 0.70 meter square, by which was a (broken) clay pot [Plate XXXI, 1].

To the southeast of this grave and lying underneath the altar of the upper floor was a separate burial S. The coffin was of reeds over a wooden frame and the impression of it in the soil was admirably preserved, so that not only the individual reeds could be distinguished but even the strings which secured them one to another and to the frame [Plate XXXI, 2]. It measured 1.75 x 0.70 meter; the sides were 0.55 meter high to which had to be added the height of the gable roof.

Image Number: 191996

Image Number: 191989

In the coffin the body lay on its right side, the head northwest, the legs slightly flexed. On the forehead were two gold frontlets; close by was a twisted gold hair-ribbon, and near the right ear a gold ear-ring; round the neck a string of gold and carnelian diamond beads, a second string of small gold and carnelian ball beads, and a third of large gold balls and very large beads of carnelian, agate and steatite. Between the hands was a copper bowl, diameter 0.14 meter, stuck to which was a gold finger-ring and a pair of gold ear-rings. By the hands was a copper knife, a wolf’s tooth, and, by the pelvis, a single shell ball bead (U. 17816).

Parallel to grave S and partly underneath it was another reed coffin, burial T. The body lay almost on its back, the head northwest and turned over the right shoulder, the legs practically straight. On the head, four gold frontlets and a twisted gold hair-ribbon; near the head was a gold finger-ring and interlaced with it two gold ear-rings which evidently had not been worn but put as offerings into the grave. Round the neck was a string of small diamond beads in gold, carnelian and lapis lazuli, and a second string of small gold and carnelian ball beads, some fluted, and some large beads, the order disturbed, of carnelian, agate and lapis lazuli with gold balls. On each arm was a plain silver bracelet; by the shoulder a straight copper pin, by the hip a shell cylinder seal and a copper axe of the same type as that found in Burial R; a hemispherical copper bowl in front of the breast, and with it a copper vase, and two clay vases both of ‘Sargonid’ type, completed the grave furniture (U. 17815).

To judge by their position these were the three principal graves, and their contents were also the richest, but of the others, A, B, F, G, M, and P had gold frontlets and twisted hair-ribbons and small gold objects such as ear- or finger-rings and beads; burials C, D, J, K, L (a child’s grave), N, Q (also a child’s grave), and U were poor; the bodies were wrapped in matting or simply placed in a matting-lined depression.

Image Number: 191998

The Ziggurat [Plate XXVI]

In the season 1923-24 the top of the Ziggurat was cleared of rubble, the plans were drawn out by Mr. Newton, and a suggested restoration of the building as it was after the restoration by Nabonidus in the sixth century was published in Antiquaries Journal, v, page 9, figure 1. I was at the time in agreement with most of the details of that restoration, but since then a good deal has happened. In the first place we have learnt more than we then knew about the brickwork of the various periods; and I began to be doubtful about certain points in our original scheme. Dr. W. Andrae, Director of the Vorderasiatische Abteilung of the Berlin Museum, who visited Ur in 1926, suggested to me that the bricked-up recesses in the top stage of the tower might be ‘keys’ for securing a case-wall to the core, quoting analogies from the excavations at Babylon. At first I was not convinced, but as I had always felt that our only explanation of these recesses was unsatisfactory, I grew gradually more inclined towards his view. A further difficulty was that our original reconstruction made the Ziggurat not very much higher than the existing ruin; it seemed doubtful whether the dilapidation of such a building to its present dimensions would account for the mass of debris which we had cleared from against its walls. This winter Mr. Rose put the matter to the test by calculating the extent of that dilapidation and the cubic contents of the debris. The problem was not simple, for allowance had to be made for wind action both in heaping up sand against the building and in denuding the ruins and the rubbish-heaps, and also for the contribution made to the rubbish-heaps by the Neo-Babylonian buildings erected either against or close to the walls of the tower on each of its four sides, buildings of which very little survives as a basis for calculation. Naturally nothing like accuracy could be achieved, but on the most conservative estimate it became clear that for the tower to be buried as it was, at least four meters and probably a good deal more would have to be added to its height as given by the restoration published in 1925. But an addition to the height of the Ziggurat involved a radical change in its plan also, for the upper staircases suggested in Mr. Newton’s drawing could not be carried higher without reducing the area on the top stage available for the site of the temple to impossibly small limits or to nothing. Moreover if Dr. Andrae’s suggestion were correct the top stage would have to be remodelled altogether. The whole question of the Ziggurat had to be taken up a second time.

Further, in 1923-24 we were concerned only with the latest phase of the building. Great care therefore had been taken not to destroy any of the existing brickwork, which was for the most part the brickwork of Nabonidus, and no attempt had been made to probe into this and see whether anything of the superstructure of the earlier Ziggurat survived at a lower level. In view of our general program of tracing as fully as possible the history of the Ziggurat site, the time had come to try for further light on the Ziggurat as built by Ur-Engur, even at the cost of damage to the existing monument.

Image Number: 192000

Image Number: 192020

Only a small number of men were employed on the top of the tower, and the later brickwork was cut away only where results essential to the working out of the Third Dynasty plan could reasonably be expected; at the end of the season all the trenches so made were filled in again, both to protect the older remains and to restore the ruins to its normal appearance. A very full photographic record was made of all the Third Dynasty work found, and Mr. Rose’s plans and sections record every individual burnt brick of that work. It will be some time before all our data can be assembled and assessed, and reconstructed drawings made of the two Ziggurats; but the data are surprisingly full, and about the Third Dynasty building in particular we learnt very much more than we had ventured to hope.

Museum Object Number: 32-40-308

Image Numbers: 192008, 192009, 192010, 192010

At either end of the Ziggurat and along its northeast side there were found in situ remains of the burnt brick paving of the first terrace, giving therefore the exact height of the lowest stage of the building. On the northeast side, where the three great stairways meet, the original Third Dynasty treads were found, much damaged but recognizable, 2.0 meters under those of the Nabonidus reconstruction. The landing on which they converged was the floor of a square brick gate-tower with (arched?) doorways on all four sides, three of these serving the lower stairways, the back (southwest) door giving on to an upper flight which ran straight up to the second terrace. Mr. Taylor, in the course of his excavations in 1854, which produced the famous cylinders and led to the identification of the site of Ur, drove a wide trench from the stair landing into the heart of the Ziggurat, cutting right through the upper flight of steps, no easy task, in that they were formed of a solid mass of burnt bricks set in bitumen mortar. Fortunately his trench was not quite central, and one side of the brick mass survived. Its top, with all the treads, had been shaved off flat by Nabonidus’s workmen in order the better to lay their own bricks, but the foundations were stepped up apparently pari passu with the treads, and so may give us the original inclination of the flight and the height and depth of the individual treads. The stair massif ends against the face of the second stage.

Image Number: 192079

The containing-wall of the second stage was laid bare along the southeast end, both corners being exposed, and was traced at points along the northeast side, at stair-head, and on the northwest end. It was of burnt brick, built with a slight batter, like the walls of the lowest stage, and like them relieved with shallow buttresses; it was standing to a height of 1.35 meters. Behind the wall was a filling of mud bricks of normal Third Dynasty (Ur-Engur) dimensions, 0.23 x 0.15 x 0.07 meter. The wall and the filling presented a perfectly level surface over which lay a layer of reeds, bitumen and matting, and then the unmistakable mud bricks of the Neo-Babylonian restorer. It was clear that the original terrace had been cut down and the brickwork levelled as a foundation for the new work. From the southeast front of the terrace a cutting was made following this level towards the center of the building, and at a distance of 9.0 meters from the front a fresh mass of Third Dynasty mud brickwork was encountered; it had the usual slight batter, rose to a height of 3.0 meters, and had a width of 11.3 meters; we exposed the entire side and the east and south corners. From the description so far given it would naturally be supposed that we had found Ur-Engur’s third stage; but the facts were not so easily or so satisfactorily explained. There was here a solid mass of mud brick rising well above the actual level of the second terrace. Below the point of junction there was no distinction between the two constructions, the lines of brick running straight through from one to the other with no break of bond. The slope of the wall-face certainly was consistent with its being a true terrace front, but it must be remembered that in each stage the brickwork throughout the mass presents the same features, the courses being laid parallel with the sloped face of the burnt brick casing. The face of the brickwork had been rather roughly coated with mud plaster, which again gave it the appearance of an exterior wall, but behind this plaster the bricks were laid in the fashion usually employed by Ur-Engur for filling: that is, two courses of horizontal bricks alternating with four courses of bricks set slantwise on edge in a herring-bone pattern; moreover, of the four courses, two will have the edges of the bricks exposed, but in two the bricks will be at right angles to the rest, so that their flat sides show on the wall face and their purchase in the brick mass is reduced to minimum.9 Such a system, though good enough for filling, is out of the question for a wall face where the wall is to retain so formidable a mass as that of the Ziggurat; as it is, the bricks set with their flat faces to the wall front are being pushed out and tend to fall away. It is quite impossible that Ur-Engur’s third stage should have been built of mud bricks thus laid and should have lasted until the time of Nabonidus. Yet, in spite of the irregularities of the wall face due to the bulging of the bricks, that face shows no sign of weathering; the plaster has only a single thickness (it has never been repaired) but is intact; and there is no trace of any later casing to preserve the Third Dynasty brickwork. Our work on the Ziggurat has not yet gone so far that I can guarantee an explanation of the seemingly conflicting facts, but I am fairly sure that what we found here was a core from which the facing of burnt brick has been removed. But the value of the discovery remains, for it is tolerably certain that there has been no cutting back of the core (I found by practical experiment that it was impossible to cut back into the standing brickwork and produce so regular a face as this) and that only the burnt brick has been taken away. It is possible that the mud plaster was then applied to disguise the roughness of the core, for piety’s sake, during the interval before the new brickwork of the restorers rose up to conceal it, but it may also be an original plaster laid over the core before the burnt brick case was added;10 in either case we have only to add the normal thickness of a casing wall to get the true ground-plan of Ur-Engur’s third terrace.

Image Number: 192014

Of the Third Dynasty Ziggurat, therefore, we have the lowest stage preserved up to its full height, a second stage whose original height can be calculated from the stairway giving access to it, and the outlines of the third stage. Also we have the details of the three great staircases leading up to the first stage together with the ground-plan of the landing gate-tower and the details, including the parapet walls, of the upper flight. Further, on the first terrace, at the southeast end, we have the walls and doorway of a chamber built up against the middle of the wall of the second stage. This is a quite unexpected feature in a Ziggurat, and we cannot explain its purpose, but it is part of the original building of Ur-Engur, and that it was an essential part is shown by the fact that it has several times been repaired by later rulers: the floor has been made good at least twice, and under the pavement bricks of one restoration we found quantities of miniature moon-crescents, boats and so forth, of copper, witness to the sanctity of the chamber.

In several places additions and modifications of the original design prove that the Ziggurat received more attention from later kings than our records hitherto had led us to suppose11 and add to our knowledge of its history; but there is no serious change until Nabonidus undertook his great work of reconstruction. Again we have not yet had time to work over our material and assess its results, but it is clear that the sixth century Ziggurat was very different from that of the twenty-third century; it was much higher, much more bulky, and above the first terrace, which remained unchanged, it bore no relation to its predecessor. Having been exposed for so long to the elements it is not nearly so well preserved as the Third Dynasty construction buried in its core, but the evidence it has yielded should allow of a reconstruction plausible and in the main demonstrably correct.

Image Number: 192105

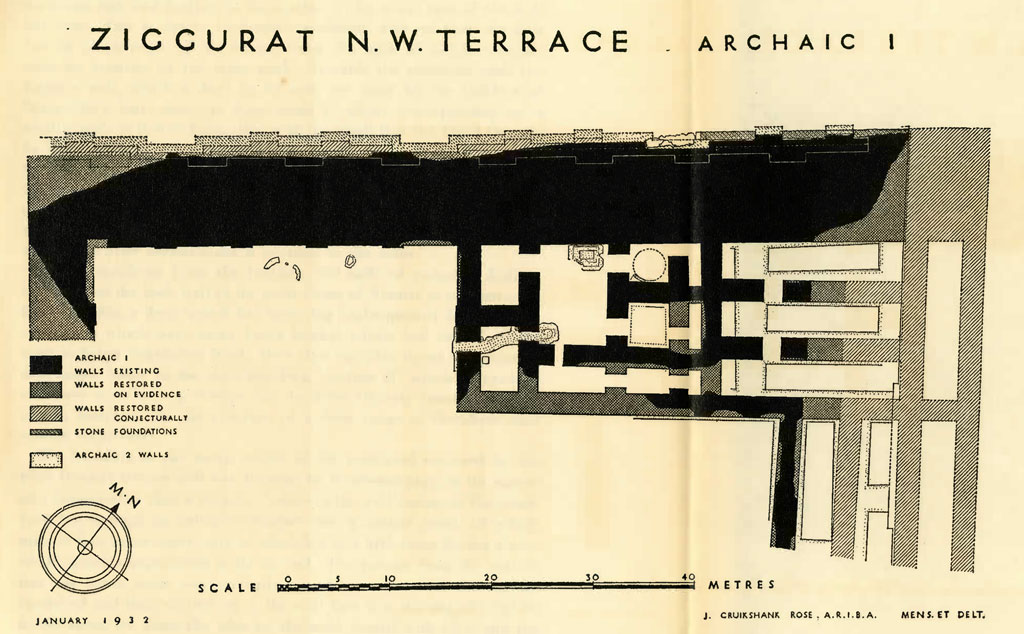

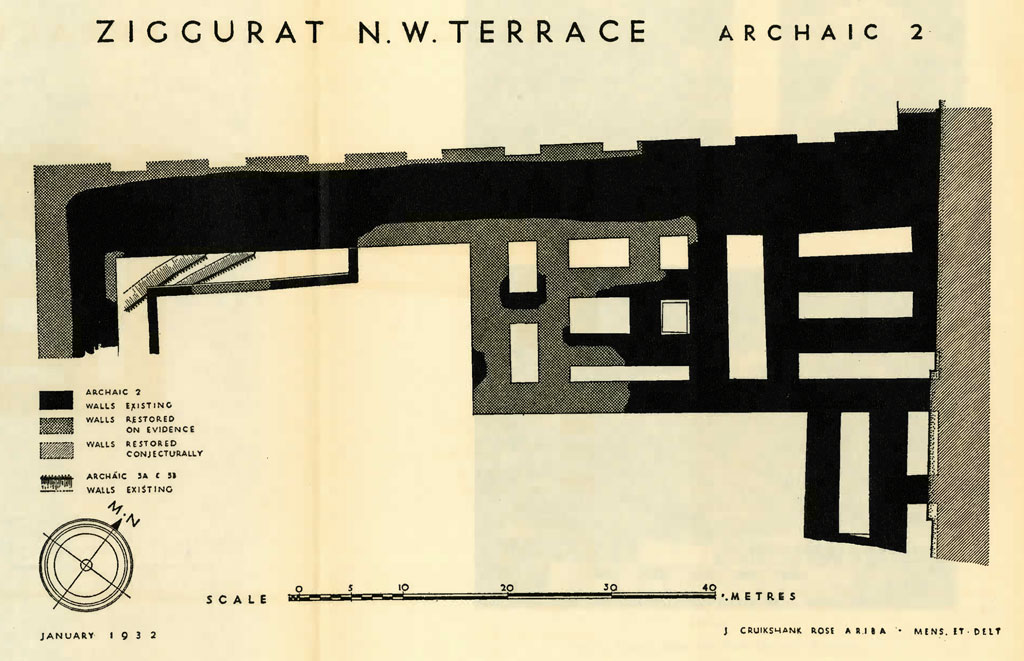

The Ziggurat Terrace

The Later Buildings

The terrace at the foot of the Ziggurat had been cleared in the season 1924-25 down to the level of the Third Dynasty, which at that time was the limit set to our researches. The remains of walls of that period, as well as those of later date overlying them, had been respected (for plans see Antiquaries Journal, v, 4, figures 1, a, b), but had since suffered so much from the weather as to retain little interest. The results of a deep cut made in 1930-31 near the north corner of the Ziggurat, where walls much earlier than the Third Dynasty had been brought to light, justified the removal of the insignificant ruins of the classical period in order to obtain evidence for the earlier stages in the history of the Ziggurat site. Already work done in 1926-27 along the southwest side of the Ziggurat had shown that the late constructions there, down to and including the Temenos Wall of Nebuchadnezzar, were founded on and virtually reproduced the Third Dynasty girdle wall, and that this in its turn was but a reconstruction following on the lines of more ancient work, some of it built with plano-convex bricks and presumably belonging to the First Dynasty. The remains on the northeast side, near the north corner, clearly ought to be examined more thoroughly, but here the area was limited on the one side by the central flight of the Ziggurat stairs and on another by the sunken ‘Nannar’ court to the northeast. The northwest side therefore, where the classical buildings already excavated might well have had forerunners of the same type, was the most extensive and the most promising field for further work.

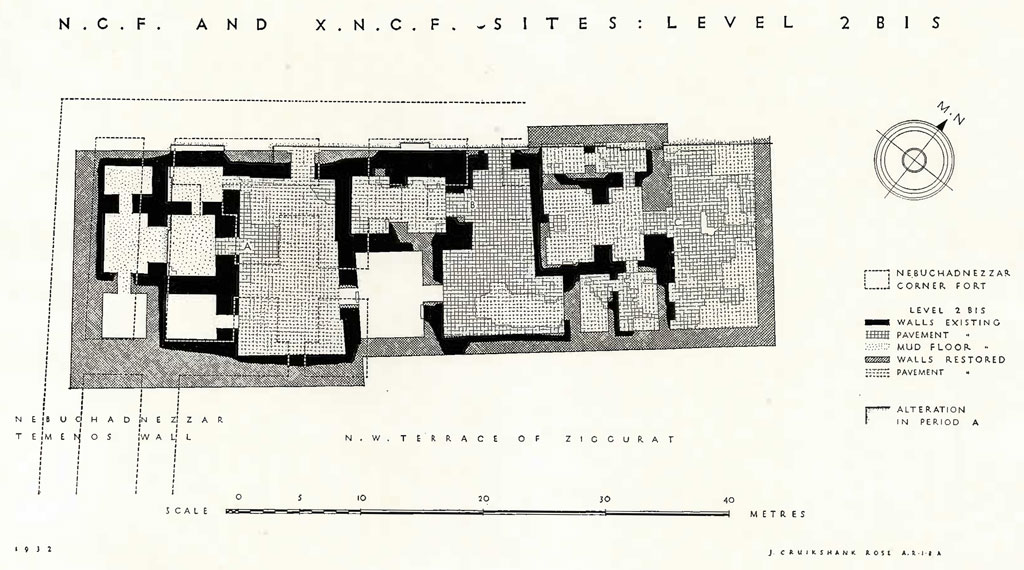

Our excavations last winter covered the whole area between the north-west face of the Ziggurat and the Temenos Wall of Nebuchadnezzar and passed round the north corner to join up with the trench cut in the previous season. They dealt primarily with the range of chambers which ran along the edge of Ur-Engur’s terrace and then turned at right angles to enclose a court of which the Ziggurat itself formed the third side, with the Nannar sanctuary of Neo-Babylonian times built in the corner between the central and northwest flights of stairs. In the course of the preliminary work of destruction certain additions were made to our knowledge of the historical periods.

Figure 3.

Image Number: 192023

Under the Neo-Babylonian Nannar sanctuary no corresponding building of earlier date was found. That the site was unoccupied under the Third Dynasty does not necessarily follow, because there had been a drastic levelling here to make room for the new building, whose foundations went down almost as deep as any of the Third Dynasty, and if there had been anything here it would have left no trace of itself.

On the northwest side two gate-socket stones of Ur-Engur, found in position, confirmed the existence of two doors conjecturally marked in our earlier plan. A more important discovery was made when the Third Dynasty walls were being removed. Of these walls there seldom survived more than the mud brick foundations. The burnt brick superstructure had disappeared and what burnt brick there was belonged to a later reconstruction the walls of which rested on the stumps of the old. The later work had been published by us as being of Larsa date, an attribution based on the character of the bricks, but its authorship was left in doubt; stamped bricks of several Isin and Larsa rulers had indeed been found loose on the site, but none was in position. Now in the mud brickwork underlying the walls of a large room northeast of the court there came to light two foundation-boxes of burnt brick each containing two copper cylinders inscribed with the name of Nur-Adad of Larsa, about 1970 B.C. [Plate XXXII]. As foundation-deposits these copper cylinders, 0.275-0.33 meter long and 0.065 meter in diameter, are unique; they are of solid metal, completely covered with inscriptions. On three of the cylinders the texts are duplicates of each other and of clay cones published in Ur Royal Inscriptions (numbers 112, 124) which are now seen to belong together; the cones came from the same building. The object of the dedication is a great ‘cooking-pot’ or oven for preparing the food of Nannar and of all the gods worshipped in the temple, that is, on the Ziggurat platform. This is of peculiar interest in view of the discovery that two chambers of the First Dynasty building of which this building of Nur-Adad is a late edition were entirely taken up by great ovens or fireplaces which we had, before the cylinders were read, recognized to be of a ritual character. The discovery, however welcome, was disconcerting at first, for the cylinders and (as shown by their measurements) the bricks of the boxes which contained them were of Larsa date, whereas the wall in which were the boxes could, on the strength of the measurements of its bricks, be assigned only to the Third Dynasty. A closer examination showed that a square hole had been cut from above into the mud brickwork and the burnt bricks of Larsa type laid around its sides; so far from the anachronism of the inscriptions upsetting our previous conclusions the paring of the mud bricks—one of which was reduced to a width of scarcely a centimeter—proved them correct.

Figure 4.

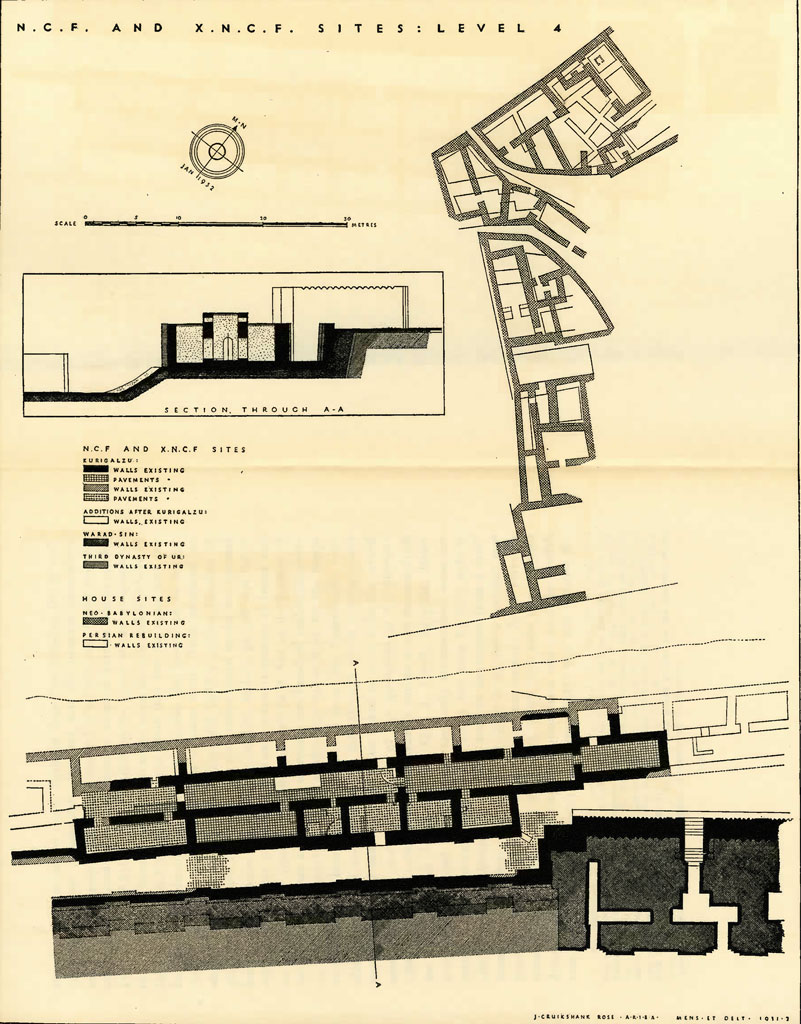

Image Number: 192035

Another new discovery lay further afield, but as it concerns the plan of the Larsa buildings published in Antiquaries Journal, v. page 353, and figure 1 (b) it were best described here. In 1924-25 we found that the mud-brick terrace wall of Ur-Engur had been refaced with a kisu or revetment in burnt brick which again we attributed to a Larsa king; projecting from this was a fort with sally-port which in its present condition was the work of Kuri-Galzu (about 1400 B.C.) but as proved by inscribed cones found in position, had first been built by Warad-Sin of Larsa; the burnt-brick facing contained bricks with the Kuri-Galzu stamp, the mud-brick core we assigned to Warad-Sin. We have now found, what we did not suspect before, that the original Larsa front of the building is remarkably well preserved, masked by the Kassite revetment, and is in itself most remarkable [Plates XXXIII and XXXIV.]

The salient, constructed in mud-brick, is bonded into the burnt brickwork of the terrace revetment, which must therefore have the same authorship. A re-entrant angle in the southwest side has the northwest face decorated with two double-recessed niches of normal type, but the whole length of the main northwest front is made up of a series of large attached half-columns with double recessed niches down their centers; this type of wall, copied later by Kuri-Galzu, now makes its first known appearance in Larsa times. The decorated facade rests on a heavy foundation stepped out in a succession of narrow offsets all of which, probably, were below ground level, so that the widening of the foundation is constructional and not ornamental; two or three straight courses at the top alone seem to have been exposed, and afforded the necessary base for the half-columns. In the center the frontage line was set back for a doorway flanked by two sets of broad reveals, and in the angles between these and the side walls were mud-brick columns in the round. The columns were of moulded bricks, segmental in shape and with the outer face not only rounded to the curve of the shaft but with a further boss in relief such that each set of three bricks (two in the lower and one in the upper course) bore a triangle in low relief; this decoration made of the column a very close imitation of a date-palm trunk, the original from which in Mesopotamia the architectural column was inevitably derived. The columns were slender, with a diameter of only 0.70 meter, and could scarcely have attained any very great height; presumably to counteract the weakness inherent in their girth and material they were tied at intervals into the side walls of the entry by courses of bricks running through. The wall was continued across the doorway, what looked at first sight like a blocking of the passage proving to be bonded into the jambs, and this original barrier rose to a height of 1.60 meters, virtually that of the interior passage-way in Kuri-Galzu’s reconstructed fort. It would appear that the Larsa doorway also was at a high level and was reached by some kind of wooden steps normally placed in the door recess but removed in times of danger, and so serving the same purpose as the drawbridge of medieval times. At the west corner of the facade, where a plain buttress framed the decorated wall length, we found definite proof of the authorship of the whole building, and with it of the terrace revetment. On either face of the buttress at a height of 1.85 meters above foundation level there was built into the wall an inscribed clay cone of Warad-Sin (see Ur Inscriptions, 131) : the stem was embedded in the brickwork, the flat inscribed base was flush with the plaster on the wall face, which had been carefully trimmed so as to leave the clay disc exposed. This discovery of the cones in position made it evident that those found in 1924 (see Antiquaries Journal, v, page 356) and then described as being in the mud-brick core behind the burnt-brick face, were really in the face of the mud-brick wall which the later burnt-brickwork merely masked.

Image Number: 192023

Image Number: 192032

Apart from the topographical interest of this, the most ornate example of Larsa building yet encountered, the fact of its including free columns is of much importance. The common employment of the column in very early Sumerian architecture is now firmly established; we have a good instance of it in the Third Dynasty (Antiquaries Journal, x, Plate XXXVI, 6), and now it recurs under the Larsa kings, while Haines, though his account was discredited, claimed to have found a columnar hall of Kassite date at Nippur. At no period therefore in Mesopotamian history can the possibility of the use of the column be discounted.

The Early Buildings

Below the level of the Third Dynasty buildings which occupied the area between the northwest face of the Ziggurat and the terrace wall of Ur-Engur there was found a not very dissimilar range belonging to the period of the First Dynasty of Ur. A very heavy mud-brick wall running along the southwest side of the Ziggurat returned along the northwest side so as to enclose a courtyard between itself and the tower; in the north corner of the court was a building protected by the wall which on this side had a thickness of 11.0 meters. The north corner of the wall had been destroyed, but it seems to have returned and continued in front of the northeast face of the Ziggurat as a compartment wall enclosing two or more, probably three, ranges of long and narrow magazine chambers. The outer wall (see the plan, Plate XXXV) rested on, and on the outside was carried down so as to mask the face of, an earlier wall which will be described later. It served as retaining-wall to a terrace whose floor level was 3.60 meters above that of the ground outside to the northwest; the exterior face was relieved by a succession of long shallow buttresses which seem in their turn to have been relieved each by two small shallow projections; the upper part of the wall face was of mud brick, the foundations or the lower part of the wall proper (it is difficult to say exactly how much was exposed) was of large boulders and quarry-shaped blocks of coarse white limestone [Plate XXXVI, 1]. The core of this unusual construction was the older wall; against the face of that, a revetment of mud bricks had been added and brought to a fairly true face up to the height to which the stones were intended to stand; then the stonework, only one course thick, had been added, with mud mortar to fill the joints, and the mud brick of the upper section of the wall brought forward over the stones; the latter were largely if not wholly hidden by a plaster of stiff clay. The stonework does not seem to have served any very useful constructional pur-pose, for it is not sufficiently bonded into the brick behind to be a source of strength, and as a ‘dry-course’ it does not safeguard the inside of the wall; it is however fully in the tradition of the buildings of ‘Archaic Level V’ at Warka12 and of the First Dynasty temple at al’Ubaid. Only a short length of the stone-work remains, giving the main wall line; the projecting buttresses have been cut away even at the northeast end, and further to the southwest the whole face of the wall has gone. This is due to Ur-Engur’s workmen, who cut back the wall for the construction of his terrace front, the back of which coincides with the frontage of the older work. Towards the northeast end, Ur-Engur’s wall, which is here in its turn cut away by the builders of Warad-Sin’s fort, seems to have made a salient corresponding on a smaller scale to that of Larsa date, with the result that the Third Dynasty builders, working out further afield, left the First Dynasty wall untouched at this point and only shaved off the projections which interfered with their ground plan. So damaged is the First Dynasty wall that our restoration of its buttressed face is necessarily rather conjectural, but the existing evidence and analogy with what went before as well as what came after should make it accurate in the main.

Image Number: 192107

Image Number: 192109

On the northeast front the building had suffered complete destruction. Behind the back wall of the great Court of Nannar as reconstructed by Warad-Sin, a deep trench had been dug (subsequently filled in with rubbish in which were many Larsa bricks) which had cut off all the walls to below foundation level. Here then our plan shows a reconstruction simply based on the older building, ‘Archaic II’, which everywhere else does serve as a prototype for the First Dynasty construction; its extent, however, and the existence of a third range of chambers must remain conjectural.

The building in the north corner of the courtyard enclosed by the First Dynasty terrace wall was, to judge by its ground plan, in the nature of a house rather than a temple. A door in the wall facing on the courtyard led through an entrance-chamber into a central court, off which opened four other rooms, one of which led to a fifth room having a very small square compartment at its far end. The passage from the outside into the inner court was carefully paved with bitumen, the surface cambered and then carried up to the wall face in a skirting effected by bricks being set along the edge by the wall, coated with clay, and the bitumen laid over them. The traffic was so considerable that the flooring had had to be relaid at least twice. In the north corner of the inner court there was a basin of burnt bricks and bitumen, the sides rising above floor level, the base sunk some 0.30 meter below it, in which were found small clay pots; it was presumably a place of offering, for it was partly overlaid by a bed of ashes witnessing to constant fires. The two chambers on the northeast of the central court were occupied one by a circular and one by a square enclosure containing lime and ashes; they were too large to be ordinary ovens and fireplaces, and may have some ritual significance.

The burnt bricks, of which the basin in the court and a somewhat similar construction in another room were built, were plano-convex bricks of the al ‘Ubaid type, measuring 0.20 x 0.16 meter. Other burnt bricks measured 0.25-0.24 x 0.18-0.16 meter, maximum thickness 0.08-0.07 meter; some had a single ‘finger’ impression, some a long narrow frog.

The mud bricks of which the house walls and the great exterior walls were built were also plano-convex and measured 0.20 x 0.14 meter with maximum thickness 0.09 meter, edges 0.055 meter. The usual construction was for three courses laid herring-bone fashion to alternate with three courses laid flat.

Image Number: 192037

Image Number: 192092

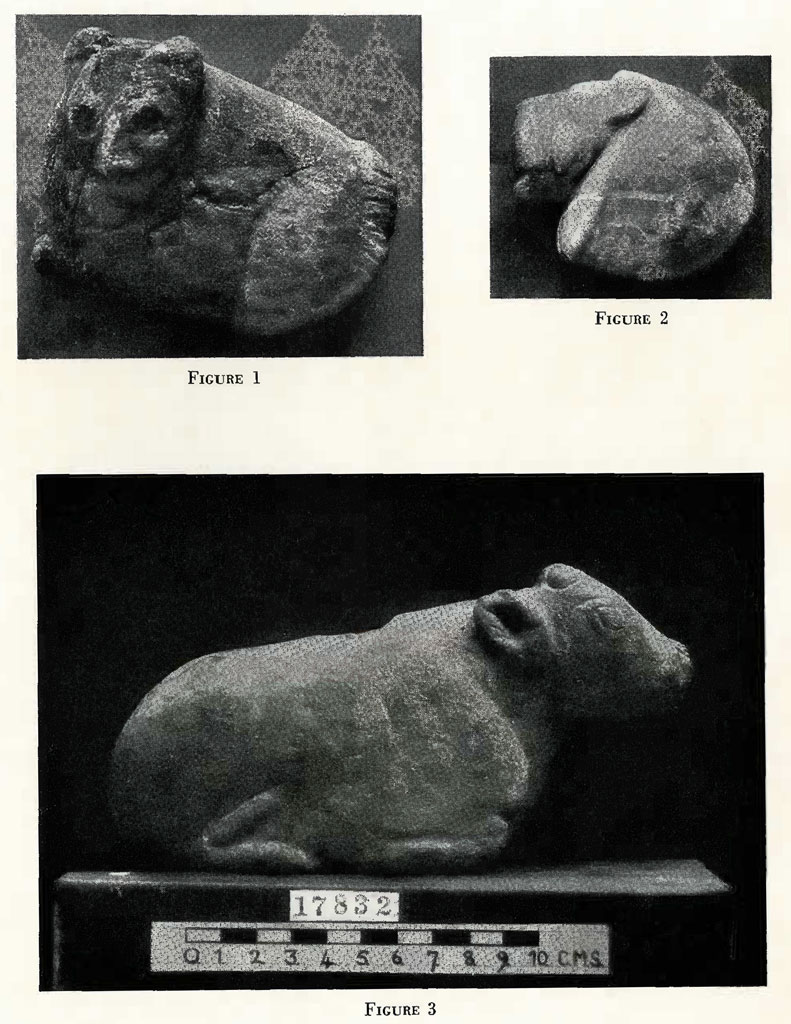

The walls of the building were of poor quality, and at the northeast end were very difficult to follow; the floors however, though only of mud, had a very solid bedding composed of nodules of reddish clay thirty centimeters and more thick; where the walls gave little evidence it was easy to follow the edges of the chamber floors and so secure the details of the plan. The outer wall was of much better quality and along the side of the main court was standing to a height of 1.75 meters. Immediately below the floor of the courtyard and certainly placed there deliberately as an offering was a large clay jar, containing a number of figures in white calcite, illustrated on Plate XXXVII.

The objects were as follows:

U. 17832. Statuette of a seated bull, length 0.17 meter, height, 0.075 meter. In the top of the back is a square hole to take an upright (?a socket for a figurine of a god?). The muzzle is damaged by decay. [Plate XXXVII, 3.]

U. 17833. Statuette of a reclining dog (?), length 0.065 meter, height, 0.035 meter. It was originally painted red and the eyes filled in with black. A hole is pierced from the top of the back to the stomach; on the under side is an engraved design of animals, mostly cut with the drill, perished and scarcely distinguishable. [Plate XXXVII, 1.]

U. 17834. Figurine of seated calf, the body in profile, the head turned outwards over the shoulder; length 0.035 meter, height 0.03 meter.

U. 17835 A, B. Two lion’s heads, silhouetted in profile; extreme diameter 0.045 meter and 0.05 meter. Originally painted red, both pierced for suspension. They are really stamp seals, the lower surface being flat, with a design of animals roughly cut with the drill. [Plate XXXVII, 2.]

U. 17836. Object of white calcite, bell-shaped with double pierced lobe; height 0.063 meter, base diameter 0.052 meter.

U. 17837. White calcite toilet-pot made of two small vases joined together; height 0.022 meter, total length 0.07 meter.

U. 17838. White calcite vase, miniature, height 0.04 meter, rim diameter 0.036 meter.

U. 17839. Copper instrument, possibly a razor, length 0.08 meter.

U. 17840. Copper disc, possibly a mirror, diameter 0.135 meter. To it is attached by corrosion a second example of the ‘razor’ type of tool like U. 17839.

U. 17841. Figurine of veined calcite in the form of a human being, very summarily treated, height 0.055 meter.

U. 17842. Beads; a mixed lot of carnelian, lapis lazuli, glazed frit, agate, shell, quartzite, crystal, and so forth. Rings, balls, double conoids, barrels, facetted lentoids, tubular, and so forth. 745 in all.

The walls of the First Dynasty building rested for the most part on the stouter walls of an earlier building (Archaic II; see plan, Plate XXXVIII) which also was completely excavated in the course of the season. Here again there was a very heavy outer wall, 9.0 meters thick, enclosing a courtyard and a building in its north corner and returning along the northeast face of the Ziggurat as a compartment-wall containing two ranges of magazine chambers. The outer wall on the northeast side had been destroyed to make room for the southwest boundary of the great Nannar Court, the foundations of which, thanks to the low level at which the court lay, went as deep as those of the predynastic structure, but as regards its character there could be little doubt. This compartment-wall and the solid wall on the northwest served as retaining-walls for a platform raised about 2.0 meters above the ground-level beyond them; the northwest wall had a series of shallow buttresses along its outer face, but the inner face was plain. The height of the platform inside it was clearly shown by the wall face, which had been plastered with mud above while the foundations below the floor were naturally left rough. The walls of the building in the north corner were standing to a maximum height of 4.50 meters, but even so were no more than foundations rising scarcely to the floor level of the court. All the chambers had been filled in with a solid packing of mud brick intended as a foundation for the pavement which had disappeared; in consequence, there were no doorways, and the ground-plan was less illuminating than it would otherwise have been; no objects were found in the rooms. A later phase in the history of the building was denoted by a wall in the courtyard running parallel with the outer wall. Its front was sloped with the batter normal in a retaining-wall and behind it was earth packing overlaid by a floor of mud brick two courses thick. It formed a terrace or platform 1.20 meters high which had been built over the original floor perhaps as the base for an altar or small independent building; a passage was left between it and the outer wall, but was blocked at the northeast end by mud brickwork abutting on the old enciente.

Museum Object Number: 32-40-454

Image Number: 192097

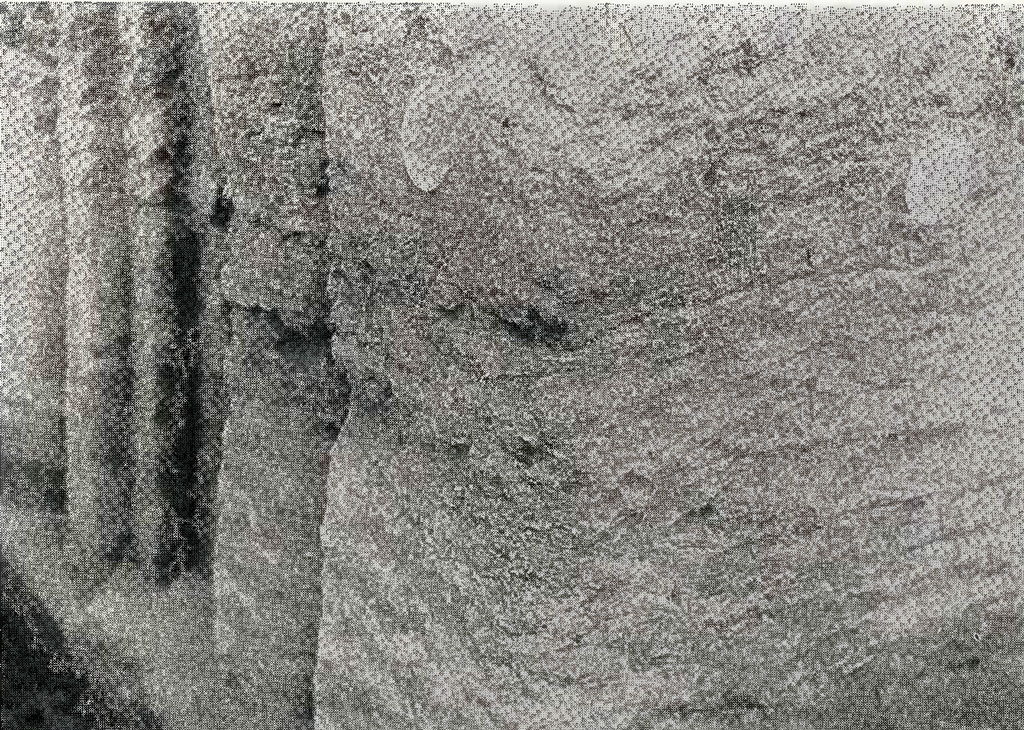

All the walls, both those of the chambers and the containing-walls of the original building, were remarkable in that they were built with a mixture of plano-convex and square bricks. The plano-convex bricks measured 0.20-0.19 x 0.13 meter with a maximum thickness of 0.06 meter, the square bricks were of different sizes, measuring respectively 0.37 x 0.23 x 0.11-0.10 meter, 0.35-0.34 x 0.23 x 0.10 meter and 0.22-0.20 x 0.13 x 0.085 meter. That all were strictly contemporary was shown by the fact that instead of the plano-convex bricks being above and the flat bricks below them, as would have been the case had the wall been of two periods, there were alternating courses of bricks of the different types [Plate XXXIX, 1] ; the small plano-convex bricks were sometimes laid flat, more often herring-bone fashion; the square bricks were always flat-laid. It follows that the structure dates from the period of transition between Jemdet Nasr and the ‘plano-convex’ age, ‘which we now know to have been of very long duration; it is hazardous to risk giving actual figures, but presumably our Archaic II belongs somewhere about 3600 B.C. It is curious that here, as in more or less contemporary buildings at Warka, fragments of al ‘Ubaid pottery occur fairly plentifully in the mud of the bricks and very freely indeed in the mortar between them. This is true both of the walls and of the filling of the chambers, which consists of plano-convex bricks only laid in courses with very little mortar.

The Archaic II building clearly served as a pattern for that of the First Dynasty, and this again was copied, at least in its main lines, by Ur-Engur and by later historic kings. The similarity of ground-plan must connote a similarity of purpose, and since the historic buildings are definitely the surroundings of the Ziggurat, we may fairly conclude that both in the First Dynasty and at the beginning of the ‘plano-convex’ period there was a Ziggurat corresponding to the buildings we have found and occupying the same site as that of Ur-Engur. Conditions are then the same at Ur as at Warka, where Ur-Engur’s Ziggurat is built round and over the ruins of similar towers of earlier date which serve as its core. Although at Ur it would be inadvisable to confirm this by excavations which would undermine and involve damage to and perhaps the destruction of the finest monument of its kind existing in Iraq, confirmation is hardly necessary and the fact of former Ziggurats having existed can safely be assumed on the strength of the evidence now to hand.

That there were yet earlier Ziggurats is at least probable. In the west corner of the courtyard of Archaic II and beneath the foundations of its containing-wall there was found a terrace front differently aligned and built of the small bricks called by the German excavators at Warka ‘Riemchen’ ; it had later been refaced or reinforced by the addition of a revetment built with mud bricks of the same type (measurements, 0.23 x 0.10 x 0.10 meter). Nor was this all. Excavations in the courtyard to the east of this early terrace edge produced a floor level of clay over which were thickly strewn clay cones from a mosaic wall-decoration. That they were older than our Archaic II was shown by the fact that the cone stratum ran under the foundations of the upper terrace wall (Archaic II b.) and had been cut away by the foundations of the great containing-wall. The cones, coloured red and black and creamy white, were of two sizes, most being of the small slender sort measuring on an average 0.09-0.08 meter in length with a diameter of 0.015 meter, while some were 0.13 meter long and had a diameter of 0.03 meter with a slight depression in the blunt end. These two types are found in situ in the same wall-face at Warka decorating a building which the excavators date as not later than the close of the fifth millennium B.C., a building which is constructed with mud ‘Riemchen’. Here the cones may well be brought into relation with the later revetment of the transverse wall, and probably belonged to buildings standing on the terrace which that wall contained [Plate XXXIX, 2].

At a depth of 0.30 to 0.65 meter below the clay floor on which the cones were lying, there was a second floor-level consisting of clay and crushed limestone on which lay more clay cones but of a different sort. They were of an average length of 0.18 meter, 0.07 meter in diameter and deeply hollowed at the end so that when set in the wall face they would give the effect of a disc of black shadow surrounded by a ring of light clay colour. Such large cones have been found (not in situ) at Warka at levels below those in which the smaller cones occur, so that the dating evidence from the two sites agrees; they would seem to belong to a stage of development between the slender mosaic cone and the clay vases which similarly decorated the face of the primitive mud Ziggurat of Eanna at Warka.13 The stratum with the large cones is probably to be equated with the older transverse wall and the cones must come from the earliest building yet known to us on the Ziggurat site; it is of course possible that, like the Warka vases, they were the decoration of the first Ziggurat itself.

The investigation of the early surrounding of the Ziggurat led us somewhat further afield than had been at first intended. It was important to locate exactly the west corner of the enclosure, which at a late period was represented by a small fort forming a salient from the general line of Nebuchadnezzar’s Temenos Wall but lying for the most part inside it: it was difficult to explain why Nebuchadnezzar had chosen this particular line—well outside that of the Third Dynasty and Kassite terrace—unless there was some earlier structure whose site he wished to include in his Sacred Area. Accordingly, work was started inside the precincts of the Neo-Babylonian fort.

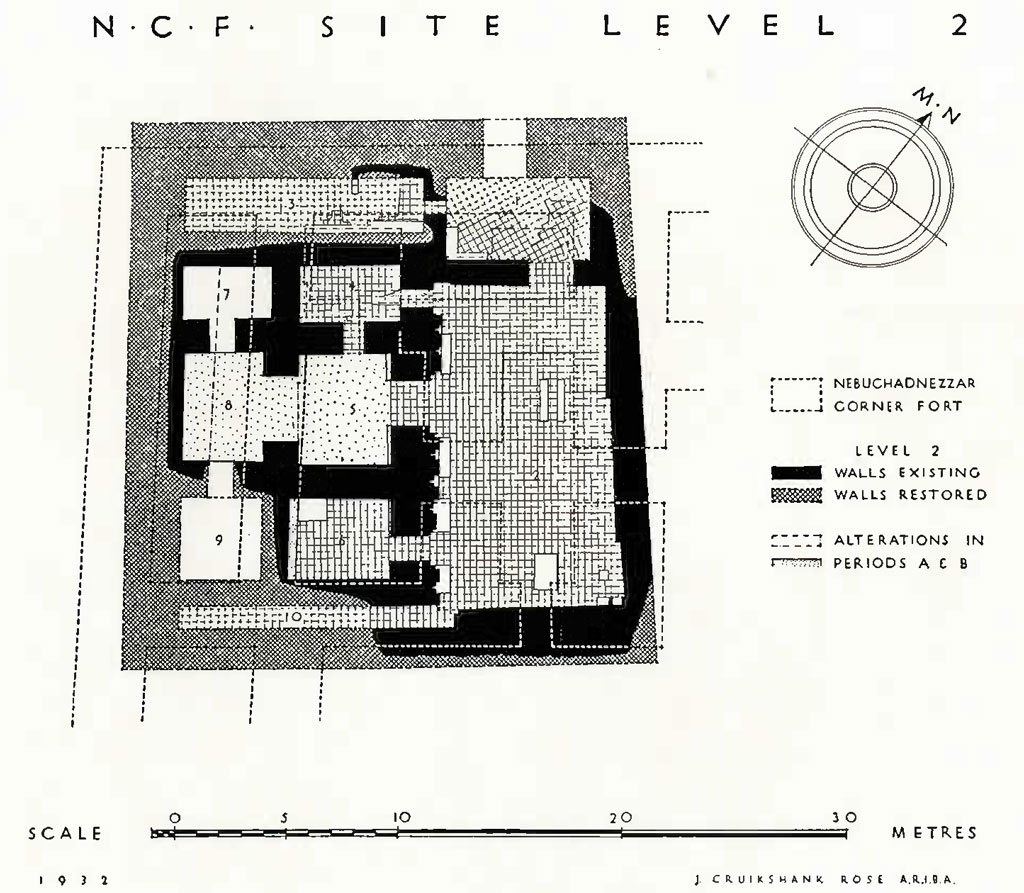

The southwest chamber of the fort was found to be occupied by a large shallow pit lined with mats which had been used as a mixing-bowl for bitumen, probably that employed as mortar in the reconstruction of the Ziggurat by Nabonidus. Below this there came to light a building with paved floors the outer walls of which (on the northwest and southwest) lay immediately under those of the fort. The building (see plan, Plate XL) was a small shrine opening on a courtyard to the northeast of it, and the entrance to the court was from the northwest, that is from the side opposite to the Ziggurat; the shrine therefore, the floor of which was at a level rather lower than the top of the Ziggurat terrace, had no communication with it. As work progressed further to the northeast it was found that this shrine was one of a number of which three were preserved to the extent that their ground-plans could be recovered in detail ; all were more or less of the same pattern, showing a court to the northeast on to which gave two-roomed sanctuaries, either simple or flanked by side chambers. Unfortunately there were no inscriptions to identify their authors or the deities to which they were consecrated. What was clear, however, was that shortly before Nebuchadnezzar’s time there was a row of shrines occupying a lower platform of the Ziggurat. Some time after they had been built, a heavy mud-brick wall had been erected along the edge of this lower platform, cutting off the approaches from that side and slightly curtailing the size of the buildings. To judge by the type of bricks employed, the wall might have been the work of the Assyrian governor Sinbalatsu-iqbi, and the shrines should in that case date to the eighth century B.C.

Further work proved that these buildings were but reconstructions of something older. The forerunners of the two chapels to the northeast had been completely ruined; enough remained to show that they had existed, but not enough to give their character. The southwest chapel, however, incorporated a great deal of the older building of which it was a simplified copy. In this underlying structure (see plan, ‘Level 2’, Figure 3) the facade of the shrine facing the court was of burnt brick and was decorated with double niches; immediately in front of the doorway was a brick altar, and in the east corner of the court there was, against the southeast wall, a double niche containing a raised base, and another altar in front of it. A door awkwardly contrived in the south corner gave access to a very narrow passage which may have contained a staircase (the southwest end where the stairs should have been was ruined away) and corresponding to this there was a long narrow chamber in the west corner of the building, entered from a forecourt whose walls had for the most part disappeared; the brick pavement served to define its limits, and a curved line of paving-bricks denoted the position of the outer door. Here again there were no inscriptions to identify the builder and establish the date of the building.

The irregularities in the pavement of the court clearly showed that there were more ruins to be discovered beneath it [Plate XLI, 1, 2]. They proved to be those of two small two-chambered shrines set side by side (see plan, ‘Level 3’, Figure 4) perhaps again belonging to a series of similar shrines, but of others no remains survived. These were oriented otherwise than the shrines of ‘Level 2’ and ‘Level 2 B’, the entrances being on the southeast and opening on to a lane which ran along the foot of the upper terrace of the Ziggurat; the facing of burnt brick added to the terrace by Kuri-Galzu had fallen into ruin and much of the brickwork had been carried off as a building material before the shrines of ‘Level 3’ were set up.

The two little shrines were of much the same pattern. In one the inner room or sanctuary is almost entirely taken up by a large brick base, in the other there are two brick bases again almost filling the room. The walls were of burnt brick, the floors had been of clay laid over brick rubble; flanking the outer door of one, there were two rectangular brick bases, and two more seemed almost to block the northeast end of the lane just beyond the shrine door. The construction was poor, and much of the outer (southeast) wall had fallen forwards into the lane in masses whose bricks still adhered together; in two places carefully squared stone slabs had been substituted for bricks. Against the middle door of the northeast building the door-socket stone was found in place, but it was uninscribed. Again the bricks bore no inscription, and measurements told nothing, for the walls contained a medley of bricks of all periods down to the Kassite; a fragment of limestone with an inscription of Kuri-Galzu found lying by the communicating door of the northeast shrine certainly did not belong there. A curious discovery was made in the sanctuary of this building; partly under the pavement and partly in the thickness of the northeast wall was a collection of clay models of plano-convex bricks (usually with a symbol incised on one side) square bricks and mixing-bowls for bitumen. This reverence for the primitive brick type is paralleled by the custom in Neo-Babylonian times of enclosing the papsugal figures buried beneath house-floors in boxes made of plano-convex bricks: it was perhaps for the same reason that in ‘Level 2 B’ the floor of the courtyard of the northeast chapel was paved with plano-convex bricks and with bricks of Dungi.

In the lane, against the shrine wall, was found the coarsely-carved head in white limestone illustrated on Plate XLV, 1. A more remarkable discovery made at the same level was that of the granite stele shown on Plate XLII, 1. The stone is 0.25 meter in height and is a very hard coarse-grained red, black and white granite; no cutting tools have been used on it (presumably the stone was too hard) but the relief has been produced by rubbing or grinding with sand or emery. On the front is the seated figure of a god behind whom is an attendant standing with a staff or fly-whisk; on the narrow edges are two standing attendants and on the back is an inscription in large straggling characters of which the middle has been intentionally defaced. What survives of the text gives us the names of Ur-Nina and of his grandfather: his father’s name and that of Lagash have been hammered out. Various monuments found in past seasons have borne witness to a Lagashite domination at Ur; this stela would lend support to the view that such domination began with a victory of Ur-Nina, and it is perhaps to him that we must attribute the overthrow of the Second Dynasty of Ur.

In all our excavations at Ur there has been hitherto an almost com-plete blank in the record of building construction between Kuri-Galzu in the fourteenth century B.C. and Sinbalatsu-iqbi in the seventh; frag-ments of brick paving by Adad-aplu-iddi-nam (about 1050 B.C.) in front of the Ziggurat and in the great court of Nannar were the sole exception to the rule. The interest of these unfortunately nameless ruins on the lower terrace of the Ziggurat consists largely in this, that they serve to to Kuri-Galzu’s fort15; by omitting the end chambers on the inside of the corridor, the magazine building was made to follow the outline of the fort salient; the unity of the scheme is obvious. The probable reconstruction of the magazines is given by the section on Plate XLIII; the store rooms would probably have flat roofs sloping slightly outwards for drainage and the roof of the corridor would be raised so as to admit light by clerestory windows, the roof sloping either to one side or, less probably, to both from a central ridge; none of the walls is thick enough to support brick vaults. At Babylon the store-houses attached to the Ziggurat formed quadrangular enclosures below the terrace; the range of chambers on the lower terrace at Ur are clearly magazines and must correspond to those at Babylon.

When these buildings were found, the season was so far spent that no attempt was made to go below them and discover whether they followed an earlier model; but during the last days of work there did come to light, in front of the fort salient, splendid walls of the Larsa period, standing as much as 3.50 meters high; there was no time to excavate properly these important remains, which must be related to Warad-Sin’s mud-brick fort.

The discovery of the lower terrace adds much to our picture of the Ziggurat. Separated from the houses of the town by an open space, which at the point where we have dug is no less than 11.0 meters wide, Kuri-Galzu’s terrace-3.25 meters high—was carried up by the blank walls of the magazines built on its edge, and would give the appearance of a massive rampart shutting off the sacred area from the domestic quarter. Above the roof of the storerooms would be seen the higher buildings of the upper terrace whose walls again would make an inner line of defence, and the towering mass of the Ziggurat would dominate the whole; this isolation of the great monument, unsuspected hitherto, must have vastly increased its effect.