There are two ways of reaching Constantinople at present. One is by the Orient Express, leaving Paris and passing by way of the Simplon Tunnel, Trieste, Belgrade, Sofia. The other route is by sea, through the Mediterranean and up the Aegean, through the Dardanelles, and across the Sea of Marmora. I went down by rail, five days and nights from Paris and after three weeks in Constantinople, I came back by sea. The first view that I had of Constantinople was at very close quarters when I emerged from the railroad station. One who goes by sea, on the other hand, has a magnificent first view of the city from the deck of the steamer on the Sea of Marmora. This view I reserved for my leave taking.

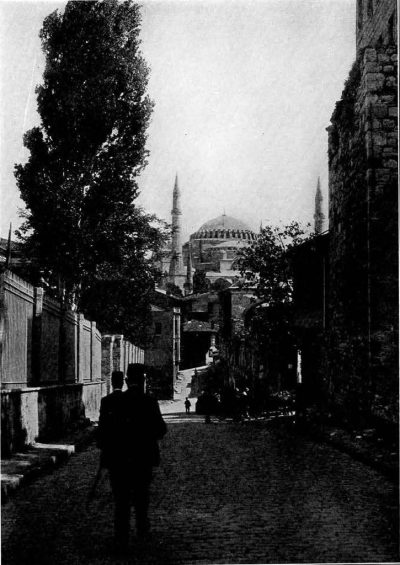

Image Number: 29321

To understand Constantinople, it is necessary to mark well its geographical position, the most advantageous in the whole world. That position is the key to its history, and its fate rests today, as it has always rested in the past, on that supreme circumstance of position. From its splendid harbor of the Golden Horn, its ships have two pathways north and south. One is the Bosphorus, leading to the Black Sea and the richest granaries of the world. The other leads through the Dardanelles to the Mediterranean and to all the Seven Seas. Both straits are so narrow that they can easily be defended against the strongest navies, a fact which was clearly demonstrated during the last war. All around Constantinople lie wide productive areas to furnish supplies and provide a field of political influence. By sea and by land, it lies at the meeting place of great highways, east, west, north, and south. The situation is also distinguished as the most beautiful site occupied by any city in the world.

Ancient Byzantium occupied the triangular peninsula between the Sea of Marmora and the Golden Horn. That is the principal part of Constantinople still and it is called by the Turks Stamboul. On the other side of the Golden Horn is Galata and Pera, the modern part of the city. On the Asiatic side of the Bosphorus is Scutari. The Bosphorus is twenty miles long and scarcely half a mile wide at its narrowest parts. A strong current flows out from the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmora. The salt waters of the Bosphorus penetrate a distance of four and a half miles into the Golden Horn which at its western end receives The Sweet Waters of Europe.

The name Bosphorus recalls the mythical origin of Byzantium. Zeus was being agreeably entertained by the lovely lady Io till Hera, the wife of Zeus, took a hand in the matter and pursued her victim with such relentless spite that the unfortunate fugitive found no rest till she arrived at the strait that divides Europe from Asia. There Io, being brought to bay, was nearly caught, but Zeus intervened at the last moment and transforming the lady into a cow, sent her swimming across to Europe where she was safe from her pursuer. Therefore, the strait was called Bosphorus, which means The Cow’s Crossing, or The Cow’s Ford. One modern guide book, written by a woman, contains the information that Bosphorus means the same thing as Oxford. Of course the good woman is perfectly right except that an ox is not a cow.

Here on the banks of the Golden Horn, Io gave birth to a daughter who, in course of time, had a son Byzas, whose father was Neptune and who, at his birth, was nursed by a Sea Nymph. Byzas founded the city which was called after him and became Byzantium’s first king. Historians reject the genealogy of Byzas but admit that there was a king of that name and they give his date as about 800 B. C.

Image Number: 29322

Image Number: 29323

Image Number: 29324

Image Number: 29325

Image Number: 29326

From that earliest date to this day, the history of the City divides itself sharply into three distinct periods. The first runs from the earliest antiquity to the year 330 A. D. when Constantine made it his capital and consecrated it a Christian city. The second period runs from 330 A.D. to 1453 when it was taken by the Ottoman Turks and made the Ottoman capital, the chief city of the Mohammedan world. The third period began in 1453 and ended in 1918 when the Allied Powers took possession. The first of these three periods may be called the Pagan Period; the second is the Christian or Mediaeval Period; and the third, the Mohammedan or Ottoman Period.

In the first century of our era, Byzantium got into trouble with Imperial Rome. She was helping Niger against Septimius Severus and the successful candidate for the Imperial throne led the forces of the Roman Empire against the city on the Bosphorus. During a three years’ siege, the Byzantines made a defense that is one of the bravest in all history. When at last the city fell into his hands, Septimius destroyed it and pulled down its walls. Then almost immediately he repented and started to rebuild Byzantium on a splendid scale. With a rapidity that is incredible today, the city rose from its ruins under the guiding genius of Septimius. Among other great works that the Emperor built was the Hippodrome which I will have occasion to describe, for it became intimately identified with the history of Constantinople in the second period. Septimius had not finished the Hippodrome when he was called away to Britain by a rebellion there. He never returned to Byzantium; in fact he never got away from Britain; the Irish question or something remained unsettled and Septimius, one of the very greatest of all the Roman Emperors, died and was buried at York in the year 211. The work of rebuilding Byzantium was then suspended for a hundred years.

Of the early Pagan city, nothing remains above ground, but its history is a most moving story. Even in those early days it was surrounded by strong walls that withstood many a siege. Philip of Macedon besieged it unsuccessfully for two years and on one dark and stormy night, he made a final effort to carry the defenses by surprise. Suddenly, the clouds were torn apart, the moon burst through, the garrison on the walls saw the movements of the enemy and the city was saved. To commemorate this deliverance, for which they gave credit to the moon goddess Hecate, the Byzantines erected a great statue of that divinity and on their coins they placed her symbol, the crescent and star. This device was adopted by the Ottoman conquerors in 1453 and it remains at this day on the flag of the Turkish Empire. Another device that may be seen on ancient Byzantine coins is the cow that represents the lady Io.

Then, once more, in the year 323 A. D., Byzantium backed the wrong horse. The Byzantines supported Lycinius in his struggle with Constantine for the throne. Lycinius took refuge in Byzantium and when that city fell to Constantine, its conqueror became sole master of the reunited Roman Empire. Then Constantine decided to make the city on the Bosphorus the capital of the Roman world. He determined moreover to make Christianity the State Religion and on May 11th in the year 330, with great pomp and ceremony, the new capital was consecrated to the service of Christ. Eleven hundred and twenty three years later, there was another ceremony of consecration; this time the city was consecrated to the service of Mohammed. That interval of eleven hundred and twenty three years coincides almost exactly with what are called the Middle Ages and it is doubtful if history can furnish a parallel to the service that Constantinople rendered to civilization during this Millennium of its glory. During that period, all the Powers of Western Europe were born and grew to maturity. During that period of their childhood and minority, Constantinople was their guardian and the keeper of civilization on their behalf. When Constantinople fell at last, the Powers of Western Europe had grown to manhood and were able to defend themselves.

Constantine’s magnificent methods would be called extravagant today. He renamed his capital New Rome and aspired to eclipse by its splendour the ancient city on the Tiber. He gave it new walls enclosing an enlarged area; he finished the Hippodrome and other great buildings begun by Septimius and he gathered into that city on the Bosphorus such treasures of art as the world had never and has not yet seen assembled. From Greece and her Isles, from Egypt, Syria, Spain, Italy, from Rome itself, Civilization sent its tribute and poured its hoarded wealth to deck the newly risen Queen.

It must be borne in mind that during the whole of its first period, beginning about 800 B. C. and ending in 330 A. D., Byzantium was a Greek city, entirely independent and self contained. It could remain aloof in its splendid isolation or it could make alliances at will and at one time it was an ally of Rome itself. With the advent of Constantine, the change was as portentous as it was abrupt. The independent city of antiquity was welded into the fabric of the Roman State, it became the Capital of that State, it became Christian, and it became Romanized. Then began that long succession of the Eastern Emperors during which period Constantinople was wicked, cruel, profligate and effeminate. It was given to turmoil and dissension; its rulers were often weak and vicious. On the other hand, Constantinople, during that same period was heroic to a degree almost without parallel in history. Though beset on every side by formidable and barbarous foes, only once was that brave city forced to yield.

Of the wonderful baths, forums, palaces, and churches built by Constantine, very little remains above ground. Of the great Hippodrome, nothing can be seen today except three monuments with bases buried in the refuse of centuries. As this Hippodrome was the centre about which the life of the Imperial city revolved, we must get an idea of what it was like.

It was fourteen hundred feet long and four hundred feet wide. One end was semicircular forming the Sphendone; the other end was enclosed by a pillared and colonnaded structure in three stories. The lower story had stalls for horses and chariots, storerooms for all kinds of equipment, and quarters for the attendants. The second story contained a royal suite of apartments for the Emperor, together with a row of boxes for the court officials. The third story consisted of twenty marble pillars, supporting a platform or tribunal on the front of which was the Emperor’s box with a golden throne. The other three sides of the Hippodrome were enclosed by the marble seats that rose tier on tier to the broad promenade forty five feet above. The seats would hold not less than one hundred thousand people. When the standing room was taken one hundred and fifty thousand people could find ample accommodation. The Hippodrome was used for the races, games, pageants, and for public meetings and demonstrations of all kinds.

Along the axis of the arena was the Spina, a thick wall four feet high with a flat top. On the Spina was displayed a wonderful collection of masterpieces in marble and bronze from all the ancient world, and in fact the whole of the Hippodrome was adorned with antique and contemporary statues and groups of sculpture and their number ran into the thousands. Four great gates gave access to the arena; the gate of the Blues, the gate of the Greens and two others without names.

In Constantinople, the populace was divided into two parties or factions, the Blues and the Greens, so called because of the colors which they wore as distinguishing badges. The Blues were the conservatives. The Greens were the radicals, the agitators, the reformers, and the trouble makers generally. There was no electioneering and there were no ballot boxes, but the rival parties had their own means of showing their convictions and expressing their sentiments toward each other. Each party was thoroughly organized, with its chief, its petty officials, and its clubs. In the Hippodrome, they sat on opposite sides of the arena, the Blues occupying the side to the Emperor’s right and the Greens the side on his left. Athletes, performing bears, horses, chariots, and charioteers were either Blue or Green; that is to say, they belonged either to one party or to the other, which gave additional zest to the performance. The races became contests between the rival factions. When one side applauded, the other hissed. When one side laughed, the other groaned. Sometimes when feeling ran very high, both sides leapt into the arena, met in the middle, and left their dead on the ground before the Imperial Guard could get their swords between.

Image Number: 29327

Of all the manifold and varied scenes that were witnessed in the Hippodrome during a thousand years: the gorgeous pageants, the heated contests, the fierce demonstrations, all the tumultuous human tragedy and comedy, I will recall five incidents to illustrate life in the Imperial City. Once the bearkeeper of the Greens died suddenly and left a sick wife and three little girls unprovided for. A day comes when the annual races are to be held. The Hippodrome is packed, the Emperor has taken his place, the races are about to begin. Through the gate of the Greens, come three little girls, aged three, five, and seven ; they pass along below the seats of the Greens, the side to which their father, the dead bearkeeper, had belonged; they are greeted with taunts and jeers; they hear no word of sympathy; they see no sign of pity. Yet, with piteous frightened faces, they pass along appealing on behalf of their sick mother for charity. A hundred and fifty thousand people watch their timid and bewildered progress. The races wait on the three little girls. The Greens feeling themselves affronted, become more noisy and insulting and order the children out. Weeping bitterly and holding hands they start to make their way back. Meantime, the Blues on the opposite side of the arena have watched this scene in silence. Now they begin to take a part. Loudly they call to the girls to come across to their side. Gently they coax them over and as the frightened children approach, they are showered with gold from the benches of the Blues. Men leap down to help them gather up the coins and still the golden shower comes down. Finally, loaded with gifts, the children are conducted to the gate of the Blues and carried home to their mother.

From that day forward, there was one little girl in Constantinople who knew exactly what she wanted and also how to get it. Her name was Theodora and when she became the wife of Justinian and Empress of the World, she remembered that day in the Hippodrome and she paid the Greens in full measure for what she and her sisters had suffered then. They were firmly and vigorously suppressed, and for many a long day the visibility of the Green was very low indeed in the capital of the Roman Empire. Not so bad for a little girl of seven and a beggar girl at that.

In the meantime, however, the Hippodrome witnessed a scene of another kind. In the early days of Justinian, the two factions came into violent conflict and for five days fighting went on in the streets. Then the two parties suddenly decided to come together, and to compromise their differences they agreed to depose the Emperor Justinian and choose another acceptable to both sides. They all went to the Hippodrome, there to give effect to their decisions. On that day the Hippodrome was packed by the noisy mob of united Blues and Greens bent on having their way and feeling themselves complete masters of the situation. Then Belisarius, commander in chief of the army, divided his small force into three parts. One of his divisions he gave in command to Mundus, and sent him to the gate of the Greens. The second, he placed under Narses and sent him to a second gate. He himself, commanding the third division, went to the gate of the Blues. Being merciful, he left the fourth gate free as a way of escape for the crowd within. As Belisarius appeared at the head of his column inside the gate of the Blues, Mundus led his column through the gate of the Greens, and Narses led his column through the third gate. The unarmed mob of some hundred and fifty thousand men struggling to escape by the fourth gate were then taken in hand by the three armed columns and when that day’s work was done, thirty thousand dead men lay within the Hippodrome. Justinian kept his throne and reigned with Theodora by his side for thirty eight years. They were years of profound peace and great prosperity for Constantinople. Everybody attended strictly to his business.

Image Number: 29328

After that day when Belisarius and his two generals cleared the Hippodrome, it was in such a mess that it was not used again for two years. Meantime Belisarius was in North Africa, where in a victorious campaign he destroyed the Vandal Kingdom. Now he was coming home bringing the captive Vandal king and a. wonderful captured treasure.

Again the Hippodrome was packed to its utmost capacity. The Emperor Justinian, robed and crowned, sat on his golden throne. Through the gate of the Blues came the long procession, Belisarius, in full armour and carrying his sword, walking in front, having refused to ride in the triumphal car drawn by four white horses as was customary, for he was modest as well as merciful. After him came his veterans fresh from battles that made the world’s history and after them came Gelimer, the captive Vandal king. Then came the cap-

tured treasure—the massive golden throne of the Vandal king, his crown, his chariot, hampers full of gold and silver and precious stones. Among that treasure was the sevenbranched golden candlestick and the golden vessels that had been taken from the Temple in Jerusalem to Rome by Titus four hundred and eighty years before and captured by the Vandals in their sack of Rome and now recaptured by Belisarius from the Vandals. It was a magnificent and a moving spectacle that was seen that day in the Hippodrome.

Let us go forward from that day six hundred and fifty years to the year 1204. The Fourth Crusade, ostensibly on it way to Palestine arrives at Constantinople, the Christian capital of the world. The city is fabulously rich. The Crusaders decide to take and plunder it. Constantinople is unprepared for the treacherous assault and the reigning emperor is a weak and foolish man. The Christian capital for the first time is captured and sacked; the palaces are spoiled; the Hippodrome is stripped of its priceless collections of art; the bronzes are melted down ; the marbles are broken up ; the whole Hippodrome becomes a ruin. Saint Sophia is filled by day and by night with scenes of revelry and lust. The greatest and richest church in the world is stripped of its treasures; the great golden altar is broken up and carried away with the golden ornaments and vessels; the seven-branched golden candlestick and gold vessels captured by Belisarius six hundred and fifty years before and taken by Titus from Jerusalem eleven hundred years before, are stolen with the rest and all this golden loot is loaded on a ship and despatched to Venice.

Image Number: 29329

The ship that carried the Crusaders’ loot from the Golden Horn was lost in a storm at sea and went down in the Mediterranean with all its treasure, and there it lies safe in Davy Jones’s locker.

The sack of Constantinople took place in 1204 and the city never recovered from the blow. Never again was the Hippodrome used, except as I shall mention, for it remained a gutted ruin. Two hundred and forty nine years have passed. The Empire has dwindled till nothing is left but the Capital itself. It is the year 1453. The Ottoman Turks to the number of three hundred thousand cross the Bosphorus and draw up before the walls. Within those walls, the Emperor Constantine XIII is able to muster seven thousand men to defend the city against three hundred thousand. On May 20, 1453, Mohammed the Ottoman leader, caused it to be made known within the city that he was going to make his supreme assault at dawn on the morning of May 29th. At midnight on the twenty-eighth of May, Constantine went to Mass in Saint Sophia, the last time that Mass was ever celebrated there. From Saint Sophia, he went to the ruined Hippodrome and there, an hour after midnight, he addressed himself to his soldiers. He begged that if he had ever offended any man he might be forgiven. He made no promises. He did not speak of victory. He simply asked every man to go with him on the walls and die fighting in the morning. The old chronicler says that the soldiers wept when they heard their Emperor’s words. But not a man faltered; no one failed him and before another sun had set Constantine XIII and his seven thousand had died fighting on the walls and Mohammed II entered Constantinople in triumph and proclaimed Mohammed the Prophet in the Church of Saint Sophia. It was the 29th day of May in the year 1453.

The Ottoman Turk is still in Constantinople. The Hippodrome has almost disappeared. Saint Sophia is still a mosque. The Turk has been a troublesome tenant in the palace of the Cæsars and it is hard enough to say any good word for him, but it behooves all good Christians to remember that it was not the Turk that destroyed Constantinople. It was the Crusader that destroyed Constantinople, two hundred and forty nine years before the conquest by Mohammed II.

The site of the Hippodrome is today in part a large open space called the Atmeidan and part of it is occupied by the great mosque of Achmet. The ground level is now twelve feet above the floor of the arena. Three monuments still standing on the buried Spina mark its position. Here is the Egyptian obelisk, here the serpents of Delphi, and here the Built Column. The Egyptian obelisk stands where it did, marking the centre of the arena. This shaft of red granite was first erected on the banks of the Nile by Pharaoh Thoth-mes III two thousand years B. C. It was brought to Constantinople by Constantine the Great, and by Theodosius II it was erected on the top of the Spina in the center of the Hippodrome. So far as I am aware this obelisk is the oldest thing to be seen today in Constantinople. Untouched by the tooth of Time and standing like a lance in rest, indifferent, scornful, contemptuous, says he: “I look back on forty centuries as you reckon time. That son of Zeus and Io that laid the first stone beside the Golden Horn is an infant as compared with me. I saw the first Phoenician galley launched when Tyre was a fishing village. I can remember the sack of Troy as if it happened yesterday. I knew Joseph and his brethren. I saw Moses turn the Nile water into blood, a trick I had seen a hundred times before. I saw Hellas rise and Rome fall. And now I hear a noise of upstart nations scrapping their nutshell navies. They don’t know where they are going but they are on their way. I know where they are going and I’ll be here long after they arrive.”

Image Number: 29330

Image Number: 29332

Image Number: 29333

In line with the obelisk on the axis of the arena a slender twisted bronze pillar rises up out of the earth in which an excavation has been made to reveal the base on which it stands on top of the Spina. You may look well at this twisted pillar of bronze, for even if you are not a worshipper of relics, it will not fail to claim your veneration. It represents three serpents twisted about each other. Their heads, now broken off, were spread apart and supported a tripod of solid gold. This serpent column stood originally in the Temple of Apollo at Delphi where it was placed by the Greeks as an offering to the god after their victory over the Persians to commemorate the battle of Platæa. On the coils, you can ‘still make out the names in Greek letters of the Greek cities that took part in the victory and that joined in setting up this monument in their most sacred shrine at Delphi. Constantine brought it to Constantinople in 330 and set it up in the Hippodrome exactly where we see it. The gold tripod was carried away by the Crusaders and the three heads of the serpents have been broken off. One of them may be seen in the Imperial Ottoman Museum.

Farther to the south on the same axis and also raised on the Spina, is a bare column built up of blocks of stone. It was built by Constantine IV as a memorial to his mother and it was covered on the outside from top to bottom with plates of brass, which were stripped off and melted down by the Crusaders. It is the most pathetic object in Constantinople. Though less ancient than Pharaoh’s obelisk by 2500 years, it strikes a very different note, where it stands in its naked decrepitude, with its piteous protest against this sorry scheme of things.

We are in Venice for a moment. Above the portals of Saint Mark’s stand the four colossal horses “shining in their golden strength.” These horses were made by some Greek artist and erected on some building in Greece about the fourth century B. C. They were carried from Greece to Rome by one of the Caesars to adorn the square in front of the Senate. From Rome they were carried by Constantine to the new capital on the Bosphorus and set up on the Hippodrome. From the Hippodrome, they were carried in 1204 to Venice by the Crusaders. Napoleon carried them away to Paris but in 1815 they were returned to Venice. During the late war when an attack on Venice seemed imminent they were removed to Naples for greater safety. Since the Armistice they have been taken back and replaced on their pedestals. These horses have not yet seen Chicago, but then time is nothing to them. They can wait.

In another part of Stamboul, rises a battered column bound together with iron hoops to keep it from falling. This is called the Constantine’s Column erected in one of the principal forums by the first Emperor at his consecration of the City. The eight porphyry drums of the shaft were brought from Rome and, in the pedestal beneath, Constantine placed the following objects: Mary Mag-dalen’s alabaster box, the crosses of the two thieves, Noah’s adze and the Palladium of Rome—the very things that any industrious collector today might acquire by a visit to a reliable dealer in Jerusalem or on Fifth Avenue. On account of these sacred relics under its base, the column was believed to work miracles and it was regarded with the greatest veneration. On top of the column, Constantine placed a bronze statue of Apollo, the work of Phidias, taken from Athens, and the public was allowed to believe that this statue represented Constantine himself.

Another antiquity is the Aqueduct of Valens, erected by that emperor about 370 and often repaired. It is a huge and impressive structure cutting through the heart of Stamboul and rising to a height of seventy feet with its twenty feet of thickness.

The ancient underground cisterns are among the most astonishing sights in Constantinople, or rather, beneath Constantinople, for the city is built over them. More than twenty of these cisterns are known. One of the largest and most remarkable is called by the Turks, The Hall of a Thousand and One Columns. These columns stand in sixteen rows and each column is built in three sections fitted into each other by means of sockets. In some mysterious way, this reservoir has become more than half filled with earth. You see only the upper section of each column and a part of the middle section; all the rest of the middle section and all of the lower section is buried. Underneath all that earth, the floor of the cistern is made of cement and the height from that floor to the brick arches is sixty feet. It was built in Constantine’s time by engineers from Rome. The purpose of the cisterns was to store water for use in time of siege and they were never empty.

Constantinople was a city full of churches for Church and State were closely united. Some of these churches are still standing, most of them converted into mosques. Just inside the city wall, on the west, stands the Church of Chora. Its single minaret shows that it is now a mosque. This little church was built a hundred years before the time of Constantine when Byzantium was still a Pagan city. It was built far outside the walls as they then stood. Hence, it is named Chora which means in the country, just as they have in London Saint Martin in the Fields. Many centuries later when Theodosius II enlarged the city, the little church of Chora was enclosed within the new and mighty ramparts of the Imperial city. In outside appearance, the Chora is small and unimpressive. Inside, it is supremely beautiful. The walls of the sanctuary itself have been plastered over by the Mohammedans, but contrary to custom they have left exposed the wonderful mosaics of the narthax and the exonarthax. All of the interior of this wonderful church was encrusted with pictures in mosaic and those which remain uncovered present a continuous succession of the most exquisite fantasies wrought in Byzantine mosaic by consummate artists. Glowing with color, these ancient walls greet you as you enter with a message of beauty from sixteen hundred years ago. The masterful composition, the soft radiance of the colors, the faithful expression, and the fine workmanship reveal a degree of skill and of artistic feeling that is not equalled in any later ecclesiastical edifice that I know. The Church of Chora presents all the characteristic features of Byzantine architecture.

The objects that I have thus briefly described, together with the world renowned Church built by Justinian and called in English Saint Sophia, are the principal surviving remnants of the great city, of which the defences still defy the passage of time as they defied all other enemies during a thousand years.

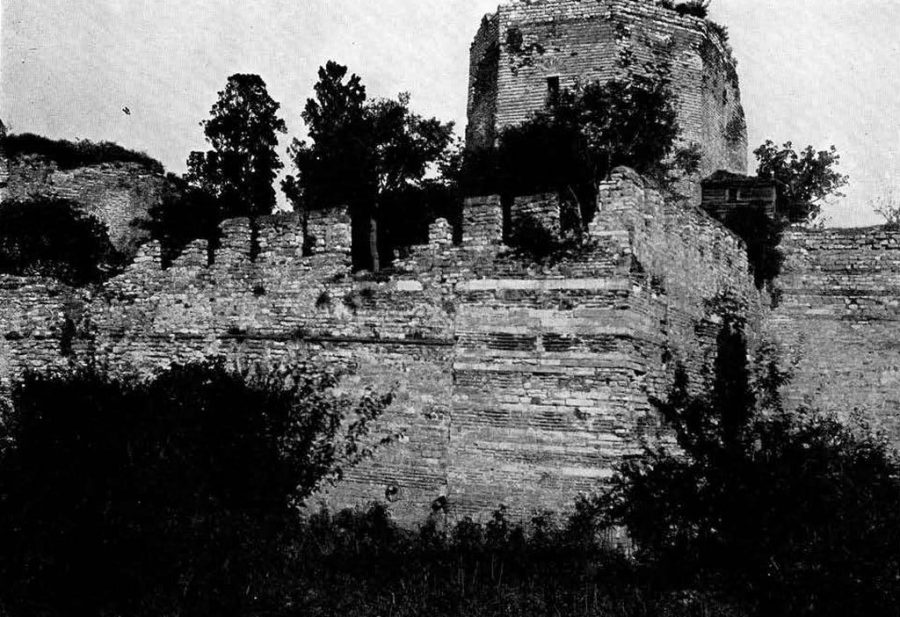

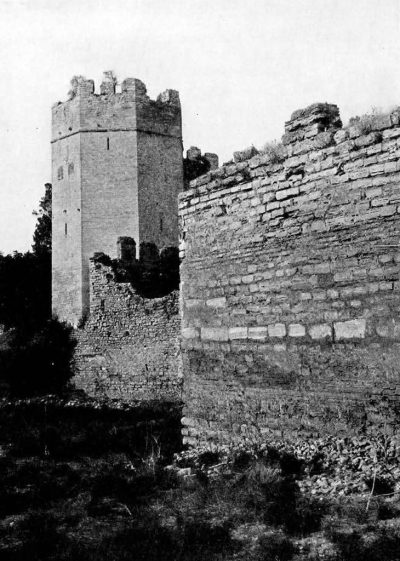

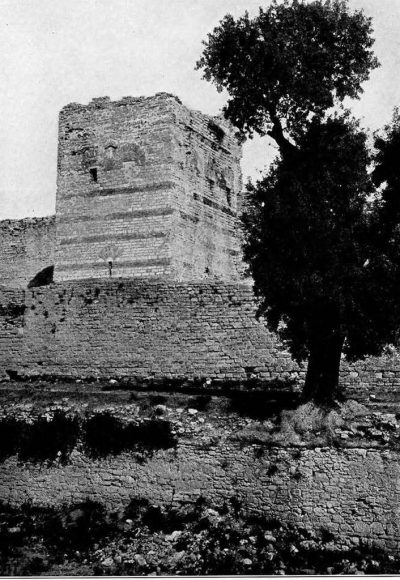

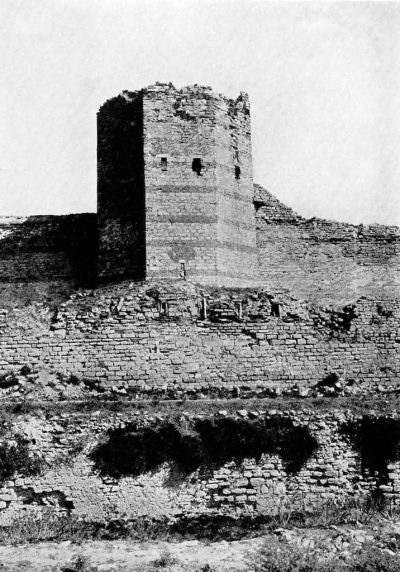

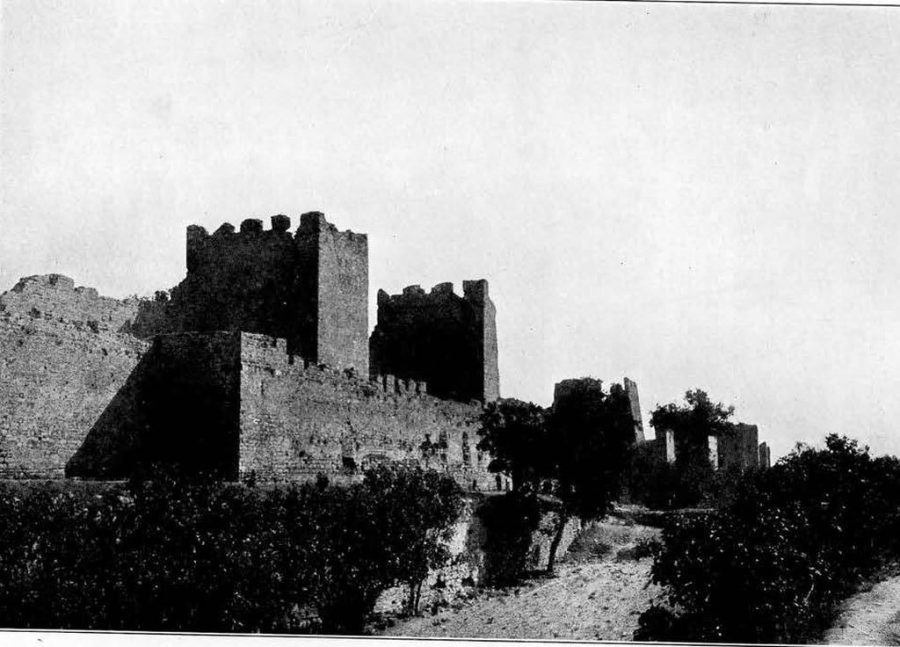

Constantinople was completely encircled by walls. A sea wall ran along the Golden Horn and was continued around the end of the peninsula and along the Sea of Marmora. Here the sea wall still joins hands with the land wall which cuts across the peninsula from north to south for a distance of four and a half miles to the Golden Horn where it joins the sea wall on that side at a point called Aivan Serai. This land wall was the most important part of the city’s defenses but there was still another defense worthy of mention. An iron chain stretched across the entrance of the Golden Horn, closed the harbor effectively against an enemy in time of war. A fragment of this chain is still preserved in the Imperial Ottoman Museum. Mohammed II, the Ottoman conqueror, was for a long time baffled by this chain for he believed that unless he had possession of the Golden Horn he could not take the city. He therefore made a shipway of planks from the Bosphorus over the hills to the Golden Horn, used a lot of grease and a great many rollers and hauled sixty eight ships over the hills and launched them in the Golden Horn.

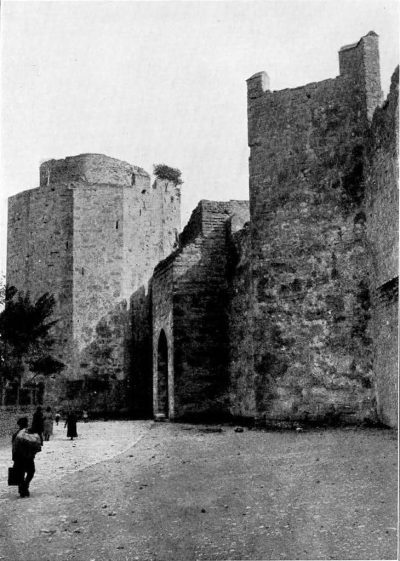

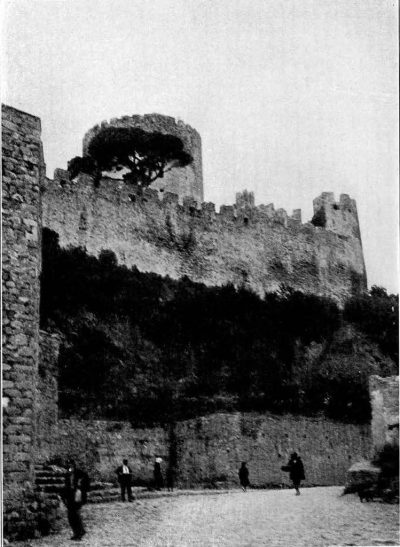

Image Number: 29334

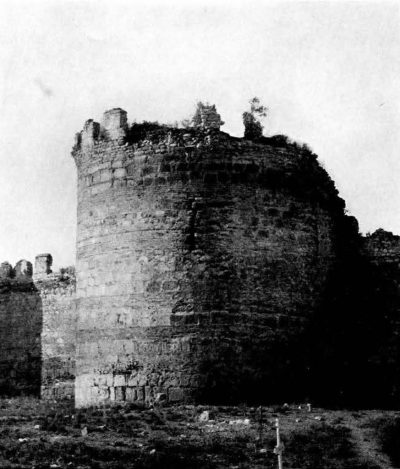

Perhaps the best preserved bit of the sea wall is one that rises from the Sea of Marmora and is known as the Marble Tower, but it is the land wall that chiefly claims our interest. The land wall had seven gates looking west. Proceeding northward from the Sea of Marmora, the first gate you come to is that famous one called the Golden Gate. It is now walled up and it was never used at all except for ceremonial processions. It was by this gate that the emperors and their generals, returning with victorious banners from wars in defense of the Empire and of civilization, made their triumphal entry into the city on their way to the Hippodrome. There is nothing left to indicate the towering strength or the splendid adornment of the Golden Gate. The walls were covered with marble reliefs that were world famous and the summit was crowned with groups of statuary in gilt bronze.

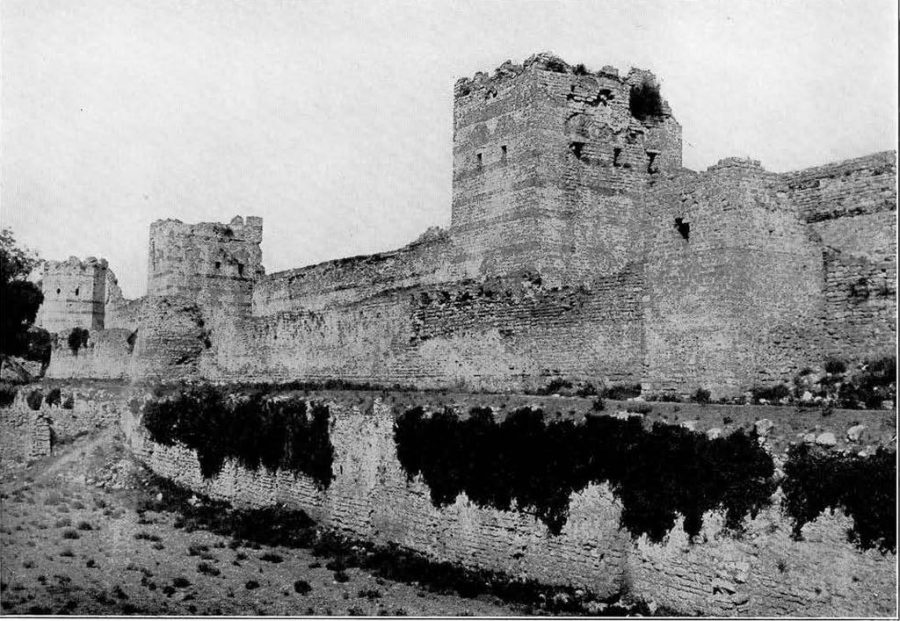

After passing the Golden Gate, one sees the land wall stretching away into the distance with a long succession of towers, some of them square, some hexagonal, and some octagonal. Presently, one becomes aware that there are two walls, an inner and an outer, running parallel to each other, and also that there is a moat. These walls were built by Theodosius II in the fifth century, with the exception of a short piece at the north end where the Theodosian wall was replaced by Heraclius to enclose a new district beside the Golden Horn. The city of Constantine had grown so fast that it was already overcrowded in the fifth century and the land walls had to be rebuilt a mile farther out.

The building of the inner wall was the first great work undertaken by Theodosius after he came to the throne. This wall was hardly more than finished when a severe earthquake threw it down in 447. The emperor started immediately to rebuild it and at the same time, decided to add the outer wall and the moat. The inner wall consists of a succession of ninety six towers united by a curtain wall. In the outer wall, there were a similar number of towers alternating with those of the inner wall and united in the same way by a lower curtain wall. In front of the outer wall was the moat. The towers of the inner wall are seventy feet high and forty feet thick. The curtain wall running between these towers is thirty five feet high and sixteen feet thick. The space between the inner and outer wall is fifty two feet wide. Between the outer wall and the moat is a space of sixty feet. The moat itself is sixty feet wide and thirty feet deep. There was an ingenious system of aqueducts that kept the moat supplied with water. The towers and the curtain walls are built of concrete faced with blocks of limestone. At intervals there are several courses of brick that run right through the structure and bind it together in a solid mass. On the tops of the towers the sentinels stood and in time of war the engines for throwing stones and Greek fire were placed upon the towers. The total thickness of these defenses is two hundred and seven feet and the height from the bottom of the moat to t he top of the towers is over one hundred feet. The length of the land wall is four and a half miles. This Heraclean wall at the northern end is single and without a moat but its huge towers give an impression of great strength.

Image Number: 29335

Day and night for a thousand years, the watchmen stood on these ninety six towers of the landward walls looking to the west and night after night, for a thousand years, these sleepless watchers sent forth the call “All’s well.” Night after night, for a thousand years, and every hour of the night, that call was taken up by the sentinel on the tower at the Sea of Marmora and it ran along from tower to tower of all the ninety six towers till it reached the Golden Horn. The only time during eleven hundred years when these towers were silent, the only time when the walls were taken by an enemy, was in 1204 when they yielded to treachery and let in the spoilers of the Fourth Crusade. They resisted successfully every other attack. From every point of the compass and from the half-points and quarterpoints, the barbarians kept rolling up against these ramparts. Wave after wave came thundering on with devastation in its wake. Avars, Germans, Huns, Goths, Vandals, Bulgars, Slays, Persians, Saracens, Tartars, Turks flung themselves in furious succession against these bulwarks and for a thousand years each successive wave was halted and rolled back. The racing tide that overwhelmed Imperial Rome got no farther than this wall. This was the rock on which it broke.

The end so long delayed came on at last. I have told you how Constantine XIII and his garrison of seven thousand defended the city against the Ottoman Turks. On this very wall the defenders died. On this very wall the last of the Cæsars fell sword in hand, claiming for his sepulchre the stateliest of cities and for his winding sheet the most gorgeous fabric ever woven by the loom of Time or by the dreams of men, the mantle of the Roman Empire.

Nothing in Constantinople impressed me like these western walls; not the wonderful view of Stamboul from the Tower of Galata; not the amazing modern city with its mosques, its khans, its bazaars, its baths and its myriad population of all races and all creeds; not the marvellous view from the Giant’s Grave, whence like Childe Harold, I saw ” the dark Euxine rolled above the blue Symplegades” ; not the spacious and lamenting void of the Hippodrome, not Saint Sophia. Nothing, in short, held my imagination and dominated the horizon of my thought like these brave old bastions, these invincible walls.

When I surveyed the scene for the last time, I was tempted to linger far into the night, mid there, amid a dead and silent world, in those still watches, a murmur ran along the battlements. It may have been the wind or it may have been the owl, but I knew perfectly well that it was not the wind and that it was not the owl, but the call and countercall of ghostly sentinels on the ghostly towers : “All’s well “. . . . . . . “All’s well.”