AMID the rugged foothills of the Wichita Mountains, on the military reservation at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, lives a remnant of the famous Geronimo’s warlike band of Apaches. Still held as nominal prisoners of war under the watchful care of the United States Army they are gradually finding their way to the “white man’s road.” Geronimo, the crafty leader of so many successful raids, fell victim to the white man’s habits a few years ago, and with him died much that belonged to the old life of his people; for the new leader, young Asa Daklugie, has turned his back upon the past and is looking forward to a new day.

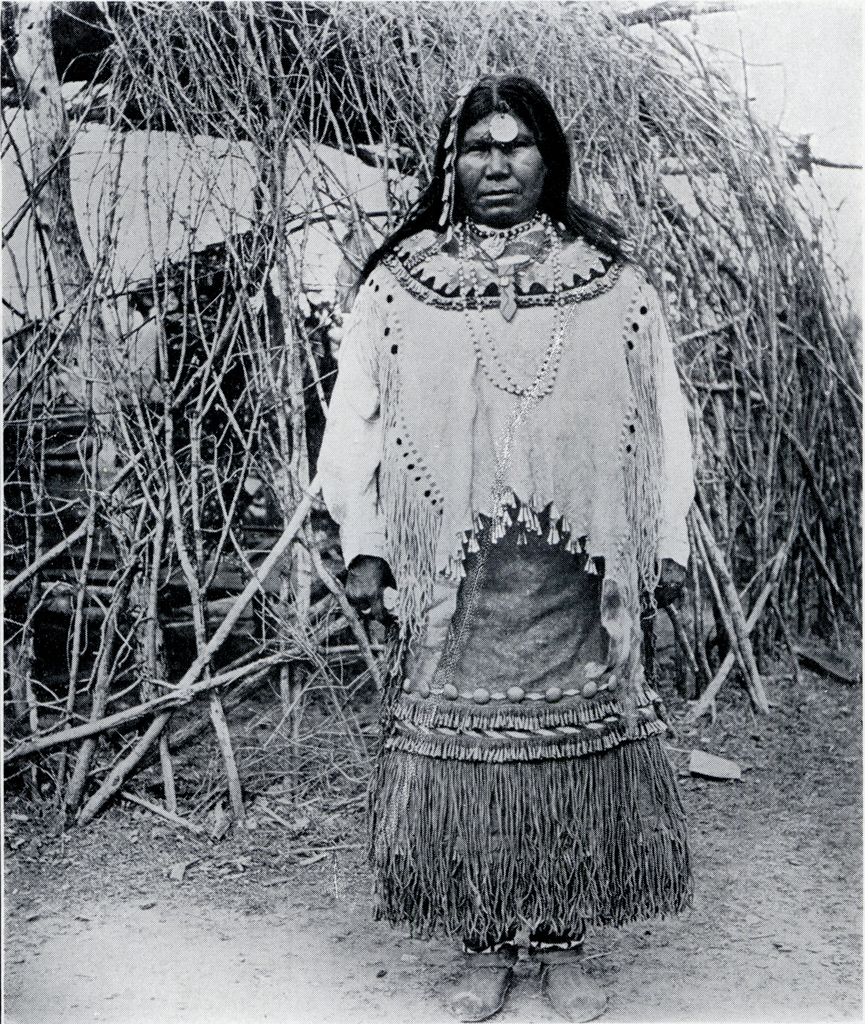

Most of the old ways have been abandoned; the picturesque native costumes have given way to overalls, boots and flannel shirts; the hunt has been supplanted by the raising of cattle, while farming in a small way ekes out the none too generous rations received at the fort.

The little and extremely airy frame houses furnished by a paternal government are occupied and appreciated when the land lies baking under a torrid summer sun, but when the icy “Northers” come sweeping down in the fall the Apaches are glad to take refuge in “wickiups” and tents erected in sheltered places in the timber along the creeks.

At first the Museum expedition, supported by Mr. George G. Heye, which was in my charge, could find little in the way of specimens to illustrate the old arts and customs; the Indians said they had nothing; but soon baskets and domestic utensils were shyly offered for sale, then such things as ornate saddle bags, the characteristic Apache moccasins with up-turned toes, and other articles of costume began to appear. After a while we were able to secure the curious charms of abalone shell, worn as amulets to prevent disease, and little figures of the Thunder God carved from the wood of a lightning-struck tree, kept to ward off thunderbolts.

One day a stalwart Apache led me aside and exhibited a great pair of branching, deer-like horns, cunningly carved from wood, and attached to a tight fitting buckskin mask or cap, intended to pull down over the face and tie about the neck. “A fine specimen for the Museum!” I thought.

When questioned about the price our Apache’s face grew solemn and he dis-coursed at length on the great sacredness of the mask, and what might happen to him if he sold, then mentioned a price that was exactly what we would expect from one of Geronimo’s marauding partisans. Taking my turn, I called his attention to the mask’s inferiority, and expressed a doubt as to whether I should buy it at all. But finally the bargain was closed at a more reasonable figure, and I drove away with not only the treasure itself but the legend of its origin as well.

The story he told me was very similar to the tales related by many other tribes to explain the origin of masks; even the Iroquois and Delawares of the East have like traditions.

“A long time ago,” he said, “an Apache named Kantaniro was hunting near a big mountain out in Arizona, when he saw a strange being come out of the rocks, a creature with no ears or nose, but which had great horns upon its head. He was badly frightened, but the spirit called to him and told him not to be afraid, and offered to help him. The hunter stopped to listen, and was told just how to make and use these masks. `Do as I tell you,’ said the spirit, ‘and I will give luck to your girls when they arrive at womanhood, will cure your sick, protect you against storms, and help everybody.’

“So when a girl reaches the proper age her parents get up a big feast in her honor and we dance several nights wearing the masks and horns, which look like the spirit the hunter saw in the mountain. At this time people who are sick can come, and the dancers cure them, for they have the spirit’s power. When all is over the girl is no longer a child, but a woman. The white people call it the ‘Devil Dance’ but it has nothing to do with anything bad. Perhaps they think the dancers look like the spirit who will take care of them when they die.”

As may be imagined I was eager to see the dance, but no chance came until the following summer, when an Indian brought me word that the great event was to take place.

Leaving Lawton, the nearest town, in the gathering dusk, we drove out past Fort Sill and down into the shadows of the Medicine Creek bottoms. Finally fording the limpid stream, we came out into a large clearing where many tents, visible in the flickering light of numerous fires, revealed the presence of a large camp.

In the middle a round space had been cleared of brush, and here various Indians were busily piling up two great heaps of logs, one to start the dance fire, one to replenish it.

Everywhere was laughing and talking. Here were heard the complex sounds of the Apache language, one of the most difficult in phonetics of any Indian language with which I am acquainted. There, from groups of sheeted visitors, the plain, matter-of-fact Comanche, and from still other groups , were heard the singsong, drawling tones of the Kiowa tongue. Altogether the scene was a noisy one, and it would be hard to imagine one more picturesque.

A modern touch was given to the scene by a flourishing soda-water booth, where some enterprising soul was doing a land-office business in pop and lemon sour.

At last the log pile was lighted and the blaze, mounting into the still summer air, made the great circle bright as day. A loud slapping sound drew our attention to a group of Indians who, squatting about a dry cowhide, had begun to belabor it, in unison, with stout sticks, and soon the measured throb of a torn-tom joined the din, followed by a burst of wild, weird song.

A hush of expectancy fell upon the audience, and all eyes seemed trying to pierce the darkness beyond the fire’s bright circle of light.

Suddenly an owl-like “ho ho ho” was heard faintly from the black void to the east, then louder and closer, until a file of awe-inspiring demons came trotting into the circle, crowned-with great branching horns, from which hung bundles of sticks that clattered at every step, and which surmounted round, hairless, earless, noseless heads, with circular mouth and eyes. Bodies were painted with black and white, while round each waist hung a fringed kilt heavily hung with metal jingles. The feet were shod with typical Apache moccasin boots, and each hand bore a sword-like or a cross-like wand. Briskly making the circuit, they trotted out to the four directions, paid their respects to the four winds with a “ho ho ho,” then turned back again to the circle.

All at once the music changed to a thrilling rhythmic dance tune, full of wild, wolf-like cries—and then began the most wonderful dance it has ever been my fortune to witness.

Gyrating and prancing, the dancing figures went through the most strenuous movements, contortions, bendings, writhings; every man exactly in time, every step in unison. The great waving horns, the sweat-streaked, laboring, painted bodies, the violent clatter of the pendant sticks, seemed as if calculated to produce a terrifying effect. From somewhere appeared the little brown maiden in whose honor the dance was held, dressed in a beautiful suit of fringed buckskin, with a great disk of abalone shell pendant upon her breast, where also hung the little bone tube through which she must drink during this, her initiation into woman-hood. With a companion, she joined the dance, moving about the fire inside the circle of horned figures, and there she kept it up, in her heavy buckskin costume, that hot July night, until a very late hour when all was over.

M. R. HARRINGTON.