Mn R. F. E. PEESO, formerly a student in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania and now a resident of Morswa, Mont., has been taking advantage of his opportunities by making observations on the Cree Indians. A collection of myths which he has made will be published in another place. The following notes and illustrations are of interest.

EDITOR.

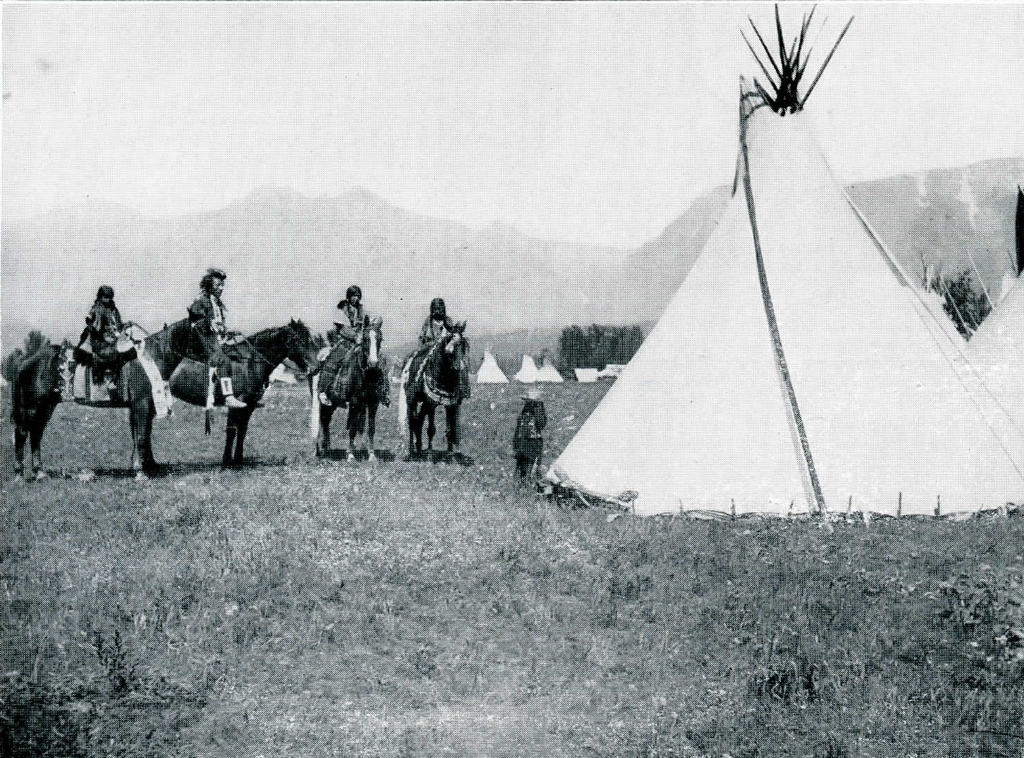

With the exception of the Chippewa, the Cree is the largest tribe of the Algonquian stock. Small bands are scattered throughout Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Physically, the Crees are not as imposing as their neighbors, the Assiniboin or Blackfeet, being of medium height and rather slightly built, but what they lack in size they make up in agility. The women, however, are noted for their comeliness. They have intermixed to a considerable extent with the Assiniboin, Saulteaux and French. The Pas-kwa-we-e-ne-wok “Prairie Indians,” resemble in mode of life and customs the other tribes of the northern plains and are said to be fairer and cleaner than their kindred who dwell in the timber. The Mas-keg-ah-wak or Swampies and Sah-kah-we-e-ne-wak or Timber Indians, resemble other tribes of the woods and are expert canoemen.

The Crees have seldom fought against the whites, although they participated to some extent in the Red River and Riel Rebellions in 1869 and 1885. After the execution of Louis Riel, in 1885, a number of them fled across the line into Montana, where several hundred still remain, but with their allies, the Assiniboin, who joined them, after breaking away from the Sioux, they waged bitter war with the Blackfeet, Gros Ventres, and other tribes to the south. They formerly ranged between the North and Saskatchewan Rivers, northeast along the Nelson River to Hudson Bay and northwest, almost to Athabasca Lake. At times they pushed as far south as the Yellowstone River. In 1835 a Gros Ventre camp of four hundred lodges was totally destroyed by them on this river. They were formerly a timber people, but were attracted to the plains by the buffaloes, and after they obtained firearms they greatly extended their territory and ranged over a vast country. In 1786 nearly half the tribe died of smallpox. They were again attacked by this disease with great severity in 1838. When trade was not concerned, they are reported to have been scrupulously honest, but in driving a bargain they would resort to all the trickery and deceit they could bring to bear. Polygamy was practiced and their morals were loose. Even before contact with the whites, they were very fond of gambling, the hand game being very popular. They had also dice games, double ball, the moccasin or hidden ball game, ring pin, guessing stick game, snow snake, lacrosse whip and top and others. They have also adopted checkers and cards. “Casino,” or “Sweep” as they call it, is popular with them.

As to their religion, they did not differ much from the surrounding tribes. The sun, moon and heavenly bodies, thunder and other natural phenomena were deified; and in a lesser way, the bear, elk, buffalo, moose and other creatures and objects. If an animal was killed, his skull or a stone representing his spirit was placed near the fireplace. Then the hunter burned tobacco or sweet grass so the words he spoke would arise with smoke to the spirit of the animal. He would say, “Give me life, food, clothes and good hunting,” or whatever he desired. He would put an old buffalo skull on the ground and poke buffalo grass into the eye and nose cavities and pray for what he wanted. Big dance lodges were erected and offerings of clothing, robes, furs and other articles prized by Indians would be hung over the stones and skulls.

Sometimes they would carve a pillar in the image of a man, which they called “Ma-to-kän”, which was stuck up outside the camp. Upon this were hung beads and pieces of cloth, and to it they made offerings, which were left until destroyed by the elements, for no one would touch what had been offered to the spirits. The Cree also practiced dog sacrifice. They also had a ceremony – of the smoking lodge they performed in the autumn. Beside the lodge they set up an image and hung clothing upon it. If any Indian needed an article so placed he might take it and leave tobacco in its place. When a child was born, the mother would make a feast and cook up some berries or some other Indian delicacy and call together a number of old men. She would tell one of them what the name of the child was to be. Then taking the child in his arms, this man would sit down and, beating time with a rattle, would sing a song directed to the spirit of the being or object that the child was named after. These songs are called We-täs-käh-täk. Then he would name the child.

There is practically no marriage ceremony.

When a person dies everything is taken out of the lodge. The body is taken out of the back or side of the lodge and not through the door. Originally the body was dressed and buried immediately after death occurred, but is now kept over night. It was dressed in its best clothes and, together with weapons, utensils, tobacco and food, placed in a shallow grave. The knees were drawn up and the body was placed on its back in a reclining posture, the head toward the north. Two or three nights after, a dead feast was held, but it was not a very large affair. While the body was being removed from the lodge, the spirit was thus addressed: “Go, go straight ahead. Don’t take anyone with you; don’t look back. And when you reach your destination, talk for us. Tell that young man not to bother us, not to come and take anyone away.” The relatives of the deceased gave everything away, the lodge and all its furnishings, their clothes, dishes and other property. Their tribesmen, however, contributed to their wants, one giving lodge, another a blanket and so on until they were as comfortably fixed as before.

The Crees had quite a number of dances:

War Dance—Pwat-se-mo-wen.

Caribou Dance—Weth-te-ko-kan-se-mo-win. This is a masked dance, the dancers making masks out of old lodge skins, buffalo robes, etc.

Prairie Chicken Dance—Pg-heyo-se-mo-wen.

Buffalo Dance—Mos-to-se-mo-wen.

Give Away or Present Dance—Ma-lä-ye-to-se-mo-wen.

Round Dance—Wäs-kä-se-mo-wen.

Ghost Dance—Che-pa-se-mo-wen.

When a person died, a lock of the hair was cut off and placed with tobacco and sweet grass and made into a bundle about a foot or fifteen inches long, wrapped in a skin or cloth. As others died, additions were made to the bundle and each year a piece of skin or cloth was added to the wrapping. In course of time some of these bundles became quite large. They were tied at the ends and hung up in the lodge. Once a year a ghost dance was held, either in the spring or in the fall. Each family would bring its bundle, which was called “Ne-yá,-che-kwa,” which implied that it was always carried along. Each family bringing a bundle is supposed to bring a kettle of soup or some other contribution for the feast.

On the first round, the dancers make the round holding up the bundles, which are then hung up in the back of the dance lodge, after which the dance continues and is concluded by a feast.

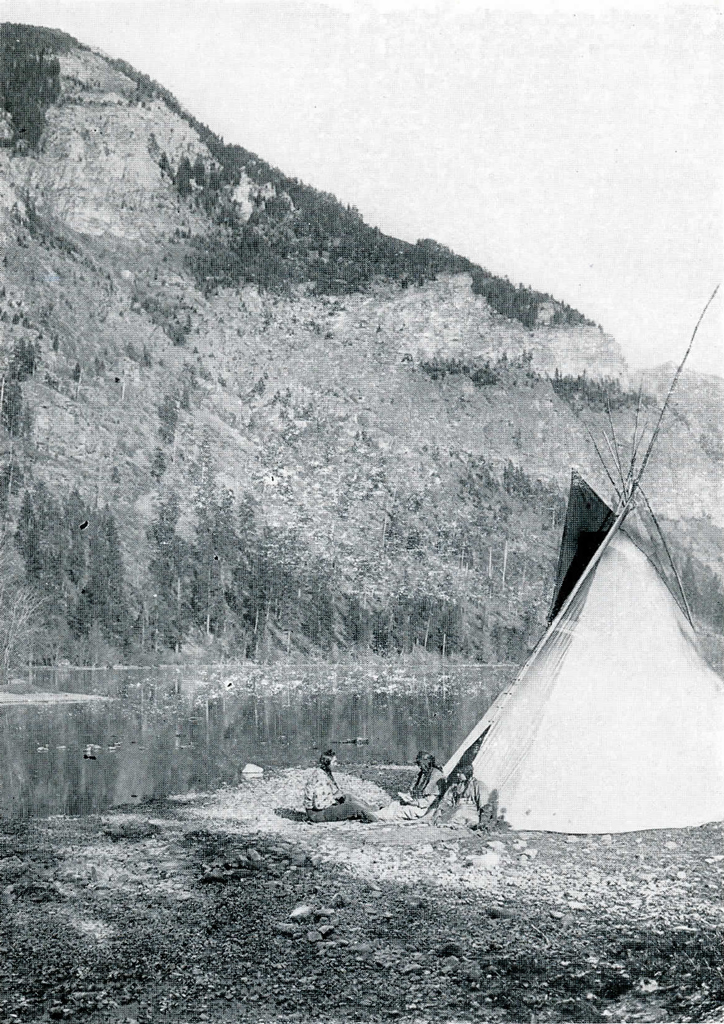

Image Number: 141890, 12958

Sun Dance—Un-pa-wa-se-mo-wen.

The Cree Sun Dance is in many points similar to that of the Blackfeet and others, but it differs in some of the minor details. A large dance lodge is erected. A centre pole is set up with side poles placed in a circle around it, supporting the rafters which radiate from the centre pole. Brush is then laid on the rafters. All the materials for this lodge are collected on one trip. A nest is made on the centre pole for the thunder (Pe-ay-so). Furs, robes, feathers, calico, beads and other offerings are hung from the centre pole and on them is marked the spirit for whom it is intended. Should a per¬son desire any particular thing very much, he makes a promise to dance in the Sun Dance. Now the dance has lost much of its original significance and ritual. The government has put a stop to the self-torture which was formerly practiced. A small fire of sweet grass is made which the dancers inhale. Then they begin to dance with their eyes fastened on the centre pole of the lodge. All at once they seem to see a face there. Then they sit down and paint their face in the same way as the one they saw. Sometimes they see an eagle, a feather or some other object there. Then the dance is continued, the dancers blowing on whistles made of eagle wing bones, sometimes elaborately decorated with porcupine quills and feathers.

When they give out, the head man of the dance gets up and makes a fire of sweet grass to which he holds the pipe which he then offers to the four cardinal points and prays for rain. Should it rain, the dancers hold out their cups to catch the drops. These they drink. If no rain falls, they drink nothing. The (lance is continued for two days and two nights, during which time the dancers neither eat nor drink (except as mentioned), although they may smoke.

The more remote bands still live chiefly by hunting, trapping and fishing for the Hudson Bay Company. Others nearer the settlements work in the woods as boatmen, and in lumber camps. The Crees are experts in the timber. Some act as guides for tourists. Many are freighters, farmers and stock raisers. They are cunning and expert workmen. Their weapons, implements, utensils, clothing and ornaments are durable and ingeniously made. Their quill and bead work designs are striking and characteristic.

The lodges are similar to others. When set up in a windy place, four poles are tied together; when in a sheltered place, only three.

The lodge is called—Ne-ke-wap.

The poles—A-pä-so-yä.

The flap poles—Kä-kä-pä-kwä-nä.