DURING the closing months of 1912 plans were completed for building an addition to the University Museum according to a modified form of the original design. It was announced at the same time that funds sufficient to complete this additional construction were on hand. The building operations which are now about to begin are the first steps taken in this direction since the opening of the present building in the year 1899. To understand the significance of this step toward the realization of a project on behalf of the people and for the advancement of knowledge, it is necessary to know something of the history and scope of the modern museum.

Some of the greatest minds of the nineteenth century applied themselves to the investigation of nature and through their labors Natural History was raised to the prominent place which it now occupies. The latter half of that century especially witnessed the vigorous growth of Natural History museums with their systematic collections illustrating the history of the mineral, the vegetable and the animal kingdoms. The public of almost every great city has thus been made familiar with the scientific interpretation of the world we live in and of the laws that shape its history.

In these museums the approved plan has been to develop the exhibits in genetic groups or series. Among these groups or series a prominent place was naturally given to that one at the head of which stands the human family. By means of this impressive argument the attention even of the illiterate was drawn to the natural relationship of our species to the world and to the universe. With this biological lesson the educational work of the Natural History museum ended so far as man was concerned. The position occupied by the human family in these systematic collections was relatively insignificant, because being based on biological affinities, they stopped with the physical aspect of the different species. Of all these species man alone presented on the other hand a fruitful mental development. This fact, taken in connection with the general scheme of classification, eventually gave rise to a new problem in connection with Natural History museums. On his physical side man fitted perfectly into the scheme, but on his mental side he was entirely apart and presented an array of phenomena peculiar to himself. On the one hand his physical structure left him among the animals, while on the other hand his mental specialization set him apart and gave him a unique position in the animal kingdom.

The directors of some Natural History museums set about to cover this last phase of evolution by adding to the subjects already illustrated in their collections, a department of Anthropology, comprising series of objects representing the works of man and illustrating the growth of human culture in its manifold varieties. Such purely human phenomena as progressive social institutions, the industrial and æsthetic arts and religious beliefs thus came to be included within the scope of some Natural History museums. Prominent examples of anthropological collections developing within the Natural History museum are to be found in the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

Of independent growth were the museums of Art, occupying a different position and confining themselves to collections illustrating the fine arts in their greatest perfection without particular reference to their earlier development.

The conditions of growth at present in the Natural History museums seem to indicate a point in the future at which the collections relating to the mineral, plant and animal kingdoms generally and those which relate to human civilization will be separated entirely and provided for in separate buildings. In the meantime the experience gained by their association has helped the development of historical and anthropological collections along systematic lines because biological methods have exerted a favorable influence on the study of History and Anthropology. At the same time the anthropological method has exerted an influence on the museums of Fine Arts to the extent that some of them are making an effort to overcome the influence of their traditions and to develop their collections with an enlarged scope and on systematic lines with reference to human history. The museums of Natural History and the museums of Fine Arts are thus being drawn together by a common interest in human history. It is likely that the result will be a division in both the one and the other and the consequent formation of a third class of museum deriving a part of its traditions from each and consisting of the human history collections and the scientific interests associated with them.

In this final division of labor there will be on one hand the Natural History museum containing collections illustrating the mineral, plant and animal kingdoms including man in his purely physical aspects. On the other hand will be the museum of Fine Arts that will aim to present examples of the best either in classical art and the art of the renaissance or else the best in modern painting and sculpture and the related arts. Between the two will be the museum of Human History, the special business of which will be to fill the gap separating the other two, and to illustrate the history of man as an intellectual being. The museum of Human History will be as much concerned with the earlier and cruder stages of development as with the more advanced, and will not be directly concerned with modern things. Indeed, since the early time of crude culture was vastly longer and more general than the later state of better things, a relatively large proportion of the collections in such a museum will be those pertaining to savage peoples, or to the prehistoric peoples of Europe, Asia and Northern Africa. The civilizations of antiquity, such as the Egyptian, Babylonian, Mycenaean, Minoan, the Greek and the Roman and all the others that contributed so powerfully to modern culture should be represented. With equal interest must be included those nations whose culture was related more remotely or not at all to our own. Among these are the nations of India, Central Asia, China, Japan, Mexico, Peru and many nameless peoples of antiquity. This seems to be the ideal towards which constructive activity in this educational movement is progressing during the present century. Each museum will approach that ideal in its own way and conform to these standards according to its opportunities and its individual interests.

The University Museum has grown up along these lines and has in a measure been anticipating the general movement for museums to illustrate the life history of the human race.

The relationship between any museum building and the collections preserved within its walls is so intimate and so important that the development of one cannot properly be achieved without reference to the other. These two phases of museum construction, the erection of a building and the assembling of collections, should proceed hand in hand in order that inward growth should mould the outward form. This is only a statement of the general principle that good architecture requires that a building should be adapted to its uses. A building not so adapted, no matter what its design, is a failure in an aesthetic as well as in a practical sense. The truth of this principle is forcibly illustrated in the designing of a museum building, which should be an intelligible expression of the culture concept which it involves.

A building which aims to embody in its contents the history of civilization in its progressive development should without adhering to any one historical style in itself represent something of the history of a architecture. If not an expression of its highest development, it should at least represent an historical phase in the art of building without advocating too clearly the claims of any one period or people. At the same time a building which would meet this demand would still fail to satisfy the requirements of good taste in architecture if it lost sight of the functions of a modern museum and failed to meet with equal directness the purely physical properties of the exhibitions and the scientific interests for which it is erected.

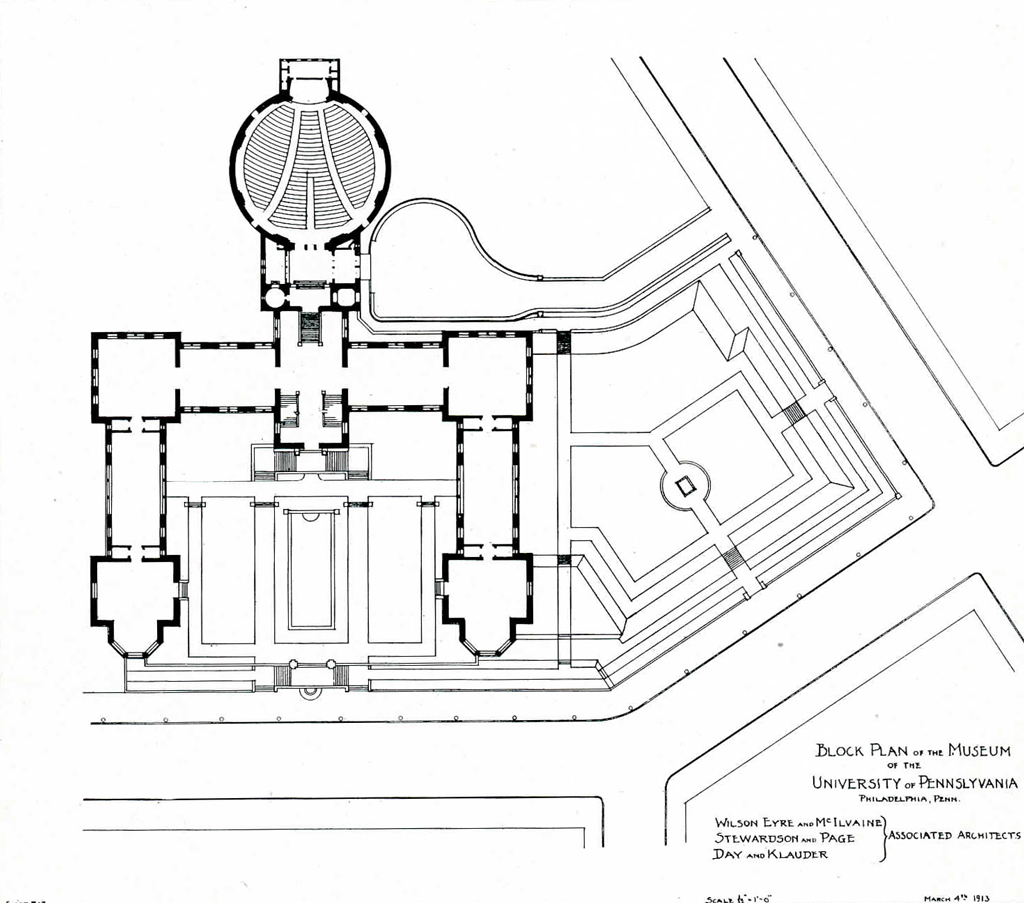

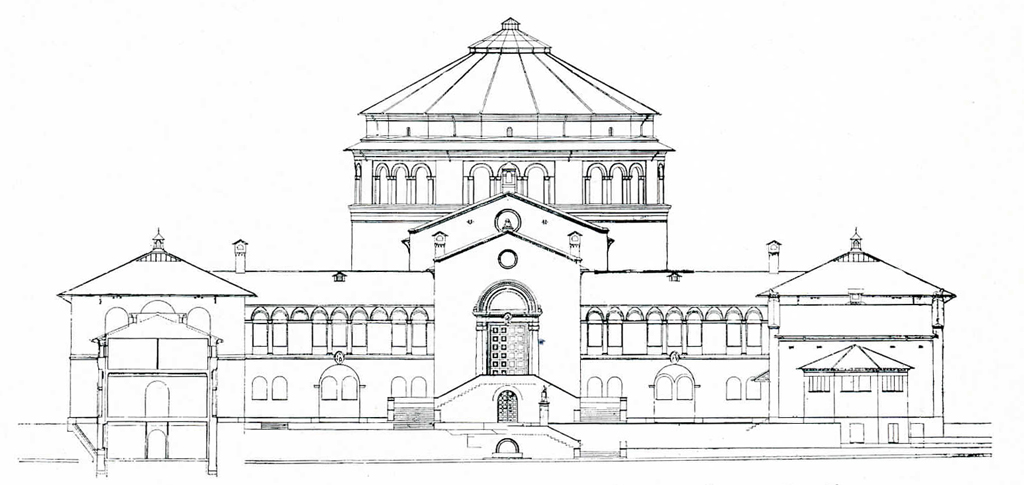

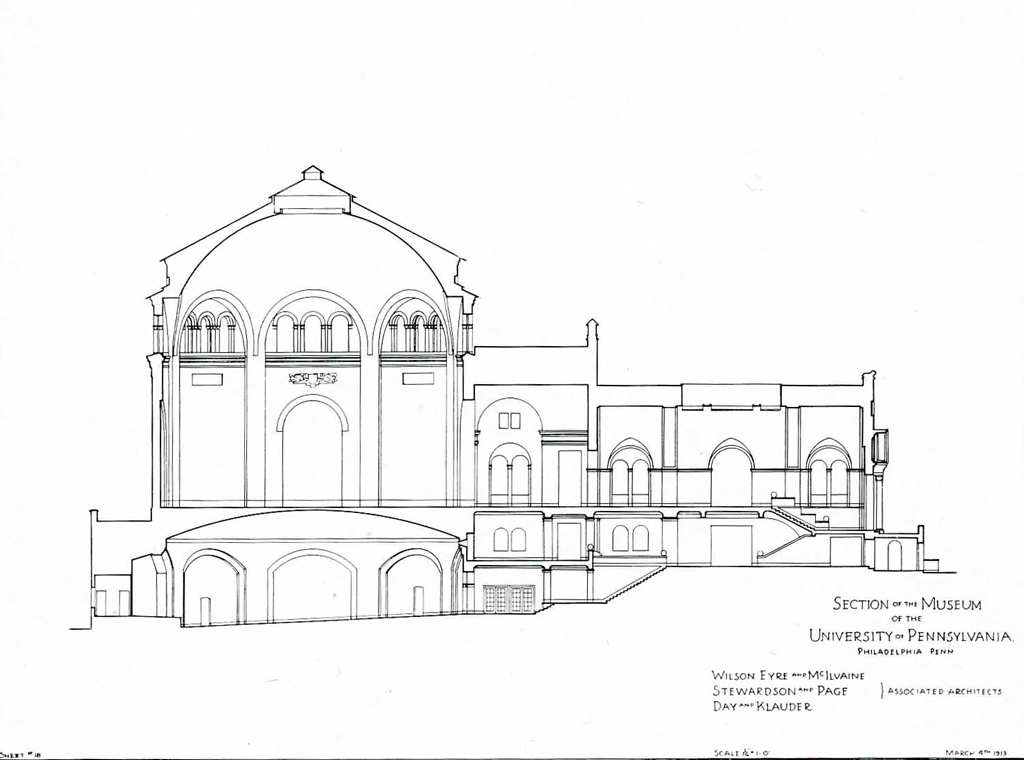

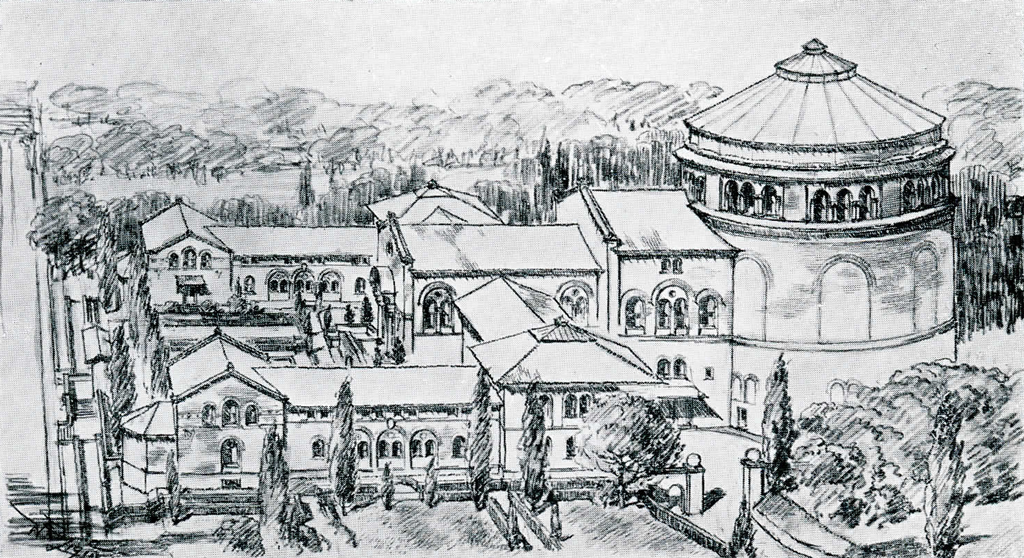

Without making claim to the attainment of so much perfection, it may be said that the architects of the University Museum have conceived a plan which in its proportions and in its design is admirably suited to the purposes of such a museum as has been described. This plan has broken away from all precedents in museum building and followed an original idea, giving rise to a building which is at once unique and adaptable. The dominant feature of the architecture will be a dome surmounting a large exhibition hall. From this hall, galleries running east and west will connect with other halls similar in form, but inferior in dimensions, also surmounted by domes which, though prominent, are dominated still by the central dome. From the two subordinate halls four wings extend, north and south with separate entrances and with courts and formal gardens between. So far as the historical style is concerned the inspiration was drawn perhaps mainly from the Roman Basilica and the Romanesque style of Northern Italy.

It is worth while to examine this plan with reference to the collections in order to see how well the building may be adapted to a consistent scheme of classification.

In its complete state there might be installed in the four main wings the collections which illustrate the four culture areas that correspond to the earlier history of human civilization. Thus, one might be devoted to the peoples of Asia, one to the American Indians, one to the African negroes and the fourth to the peoples of Oceania. Underneath the smaller domes that flank the central dome might be placed the collections of Egypt and Babylonia. In the central hall, the crowning feature of the building and underneath its dome, might be placed the artistic productions of Greece and Rome.

In the various connecting galleries, large and small, might be arranged those collections which pertain to special phases of human culture or collections that have special reference to the development of the arts. Here also might be placed the museum library containing those works of standard value that have special reference to the collections and which would be required for reference by the curators. In the basement beneath the great central hall might be placed an auditorium capable of seating two thousand people. For the administration of such a museum, a large number of storage rooms are required as well as laboratories for the scientific labors of the curators and their assistants. The building plans as they grow will adapt themselves to these needs as well as to the other requirements of a modern museum according to the teachings of experience.

The part of the building now actually in process of construction comprises the westernmost of the two subordinate domes with connecting galleries. Directly under the ninety-foot dome, lighted from above, will be the large circular exhibition hall already described. Beneath this hall and at a depth below the basement of the building will be a circular auditorium with 750 seats. This auditorium is to be fitted with every feature calculated to secure the best results and give the greatest amount of comfort to the audiences. When the time comes for a larger auditorium, it might be built in connection with the central hall and the hall devoted in the meantime to that use, might be converted into an exhibition room.

The building will be fireproof in construction and will be supplied with every possible precaution for the security of the treasures that will be kept within its walls. It will also be equipped throughout with such devices as modern methods afford for the proper heating, lighting and ventilation of the exhibition rooms, the auditorium, the offices and workrooms.

The building operations now inaugurated, it will be seen, are not intended to carry the building to completion. The larger plan which has been outlined, if it is ever realized, as every worthy object should be, will require a long period of growth and will afford a wide scope for the ability and generosity of all who are or who may become interested in this liberal undertaking on behalf of education and the people.