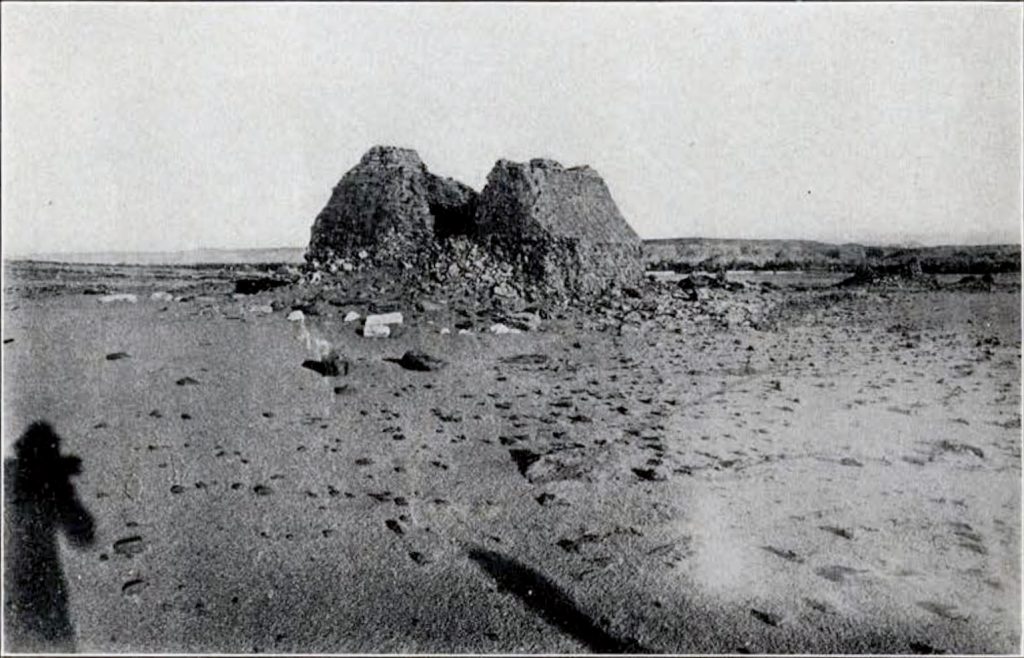

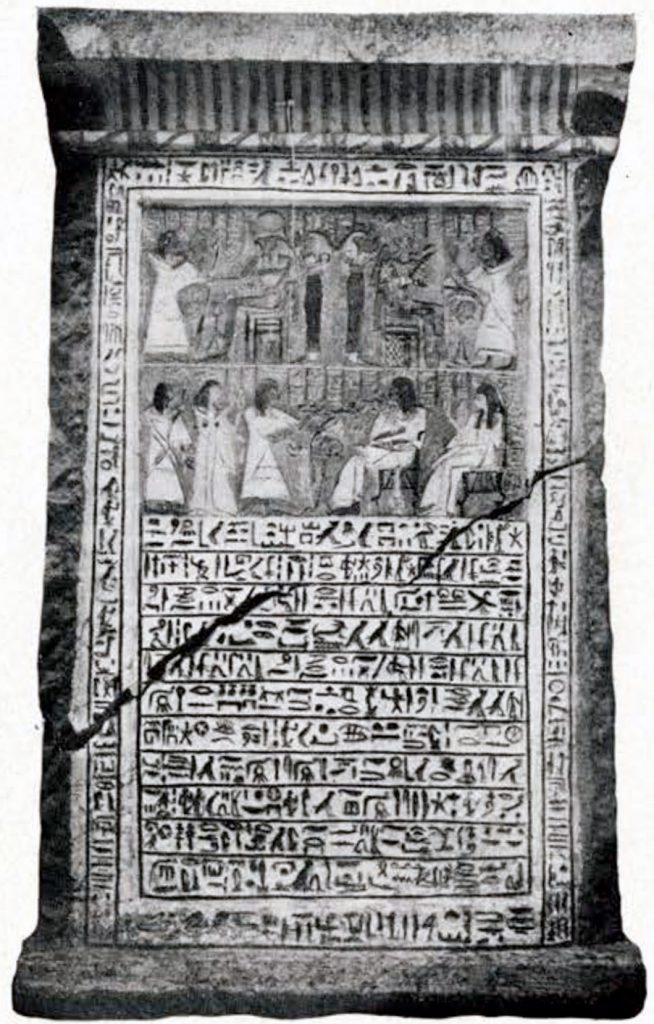

While Dr. Maclver carried on at Haifa the main work of the season, described in the last number of the JOURNAL, I was detailed to clear the town and fortress of Kara-nog, some eighty miles to the north. When the work was completed1 a little time remained at my disposal, and I turned my attention to the graves of the ancient inhabitants of Ma’am, an Egyptian town of the New Empire, whose ruins can la traced behind the modern village of Anibeh. In the high desert, about two miles from the river, stands an isolated hill wherein is cut a gallery-tomb with well painted reliefs; this is the tomb of Prince Pennut, a noble who was superintendent of the Temple of Horus of Ma’am, about 1150 B.C., and was the head of a family of important local officials. A little to the southeast of the hill is a large cemetery of peculiar interest. In all Egypt these are the only shaft graves of the New Empire that retain their original superstructures, small square chapels of mud brick with vaulted roofs, which are carried up in solid brickwork to a point, so as to give the effect of a pyramidion standing on a straight-sided podium or base (Fig. 25). The inner walls of these chapels were once covered with frescoes; thus in the tomb-chapel of Mery (Fig. 26) were painted a seated figure of Osiris, Anubis weighing the heart and opening the door of the hall, a priest clad in his leopard-skin, the sacred tree wherein stands the goddess pouring water over her two worshippers, the cow Hathor appearing from behind the western hills, and the pyramid-tomb itself with the mummied figure of Mery before it. But the mud plaster has fallen away and the paintings have almost wholly perished; the weight of the solid brick pyramids has broken through the vaults, and plunderers seeking ignorantly for booty have too often completed the ruin wrought by time and weather. It was in one of these chapels (that shown in Fig. 26) that Dr. Maclver four years ago found the magnificent painted stela or Mery, overseer of the King’s treasury in Nubia, that is now in the University Museum (Fig. 27).

Dilapidated as they are, the rarity of these superstructures makes them very important. Even more remarkable was the building that stood above a large “dromos” tomb in the same quarter of the cemetery. In front was a fore-court with brick pillars and an entrance to the east; behind was a second court, which had probably been vaulted ; it lay directly over the tomb proper, the stepped approach to which occupied its central area and had probably also been vaulted. The wall of the eastern courtyard was continued so as to enclose the western, leaving a space between the inner and outer walls about two feet six inches wide; this space was divided up by cross-walls at every seven or eight feet, and in these narrow coffins were subsidiary burials, probably of servants or retainers of the local magnate. The whole arrangement recalls that of the royal tombs of the earliest Egyptian dynasties of more than two thousand years before.

These tombs were all cut down into the rock and were reached either by a perpendicular shaft or by a stepped dromos, the pyramid, when there was one, usually standing a little west of the shaft’s mouth above the chambers; but the poorer people were buried in small graves roughly hollowed out of the shelving rock face of the desert plateau or else in the loose sand below it. They were encased in clay coffins, with faces rudely moulded in relief ; the better classes had had painted wooden sarcophagi, long since devoured by white ants.

Object Number: E11367

Image Number: 35550

Not a little of the interest of these graves lies in the fact that a good many of their occupants were members of the same noble family, whose chief representative, Prince Pennut, was buried in the painted hill-tomb behind the cemetery. The tracing out of their relations and of their offices will give us a connected piece of provincial history, while their material belongings, thus accurately dated, will be very valuable for the archaeology of a little-known period. The tombs excavated last season form but a very small proportion of the total number yet to be dug, so that nothing like all the evidence is yet to hand, nor has there yet been time to work over what we have, hut it is clear that the Pennuts of Ma’am filled for some generations most of the principal offices of the district. Thus Mery, Overseer of the Treasury in Nubia, whose stela is figured above, was the seventh son of Prince Pennut; his youngest sister, Thy, Songstress of Horus of Ma’am, seems to have married one Hornekht, who at one time held the same office. This Hornekht had made his sister, Tanezem, Songstress of Amen, a pretty blue gaze stela which is now in the University Museum.

Other sons of Peanut were scribes, priests, and temple officials; his grandson, another Peanut, who lived during the reign of Rameses IX (1142-1123 B.C.) was buried under one of the better preserved pyramids, which he shared with one Weseremnetef, presumably a relative, the fragments of whose stela, now in the Museum, show that he too held office in Wawat, the inter-cataract region where Ma’am stands. Amongst other titles of people not necessarily connected with the family we have that of a person already known in history, Messui, Viceroy of Cush in the time of Siptah; of Pentaurt, Captain of Troops in the days of Seti I; of Dwaha, chief priest of Horus of Shenyt; and of a deputy of Wawat, Mahu. The tombs had been very richly furnished, and though plundered in antiquity had not been subject to that repeated robbery in ancient and modern times from which the cemeteries at Northern Egypt have suffered; consequently, though only a small number were opened, they produced a considerable quantity of fine museum specimens now on exhibition.

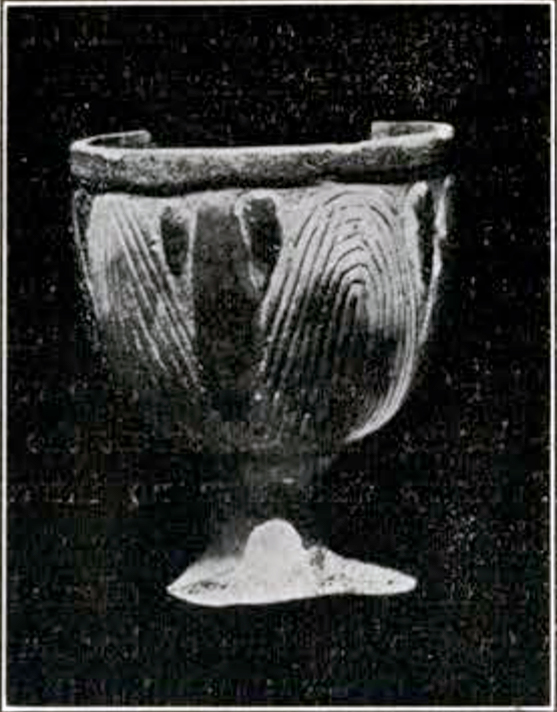

On Fig. 28 is shown a statuette of Mahu, Deputy of Wawat; it is carved in red sandstone, the color heightened with a wash of haematite and the details picked out in black and yellow. Several statuettes of limestone were found, but the paint with which they were originally covered was much faded and the inscriptions had disappeared; a more unusual specimen is that on Fig. 29, a beautifully carved though conventionally treated statuette of steatite which has been glazed with the vitreous glaze generally applied to scarabs; it is perfect except for the feet, which have been broken away. The personage represented is yet a third Pennut, whose relation to the great family is not at present clear. Another remarkable object is the faience cup or chalice on Fig. 30; it is moulded in relief as a lotus flower, a type not in itself uncommon ; but in this case, instead of the usual blue glaze being employed, the stem and outer petals of the flower and the interior of the cup are in a dead blue-black, the inner petals are white, and within these again are petals of a deep red. In the same tomb as the sandstone statuette of Pennut III were found numerous pieces of colored faience inlay; the original background, which was probably of wood, has disappeared, but the glaze silhoutte can be reconstructed as showing a man in the attitude of prayer before a cluster of papyrus reeds and bullrushes. These three objects throw a novel light upon one of the minor arts of the nineteenth dynasty.

Object Number: E11156

Image Number: 33229

The pottery, though plentiful, is not remarkable, the traditions of the eighteenth dynasty being for the most part faithfully followed and but slightly developed; one curious vase has the face, arms and breasts of a woman modeled in relief. From an unfinished tomb came a magnificent vessel of Cretan fabric decorated in creamy white and chocolate color, with bands of running spirals and marguerites. The specimen, according to Dr. A. J. Evans, falls very early in the period Late Minoan I, and should be dated about 1600 B.C.

A large number of scarabs were obtained bearing the traditional name of Thothmes III, that of Amenhotep, of Sety, of Rameses II and of Queen Tausert. Two specimens were unique; one, now in the Cairo Museum, is a large heart-scarab of steatite with its wings widely extended, the markings on these and on the back picked out with gold foil; another, also of steatite, represents the sacred beetle perched on a pectoral of beads with hawks’ head clasps carved out of one piece of stone; these two came out of the same tomb. Two daggers of bronze with ivory handles were found in another tomb; they are of the regular eighteenth dynasty type; a small fragment of a vessel of blue and white glass with human figures moulded in relief upon it bore witness to the treasures that early plunderers had destroyed.

C. L. Woolley

1A report on this work is now in process of preparation.

Fig.31.— Vase of Cretan Fabric.

Object Number: E11264

Image Number: 33222