Any handbook on Greek vases, every general discussion of them, posits the statement that the vases are of the highest importance for their illustration of the myths of Greece, not only in the literary version handed down by the epic and dramatic poets, but also in variant local forms, which are traditional and perhaps more popular. The use of the word illustration here is unfortunate for the word is a bit ambiguous. In fact so eminent a critic as Karl Robert writing Bild and Lied definitely denied that Greek vase painting can be called illustration. Robert would have illustration beginning in Alexandrian art; and others would say that illustration is a relatively recent artistic development. Illustration in its broadest sense, however, is old as art itself. The painted reliefs in Egyptian tombs, the Madonnas of Christian iconography, the bulk of Indian painting and Chinese Buddhistic art, even the greater part of derived linear decorative patterns—all are basically illustration, even though we never think of them as such.

Museum Object Number: MS1752

Illustration explains in terms of line and contour something which has been previously expressed in words. It therefore presupposes a text which offers to it an excuse for being; it is dependent upon it, and consummates its highest purpose only in connection with that text. Of course, illustration may permissibly and justifiably give aesthetic pleasure, but pleasure is not the sole reaction from any illustration pure and simple. Because of the overshadowing of the illustrative by the aesthetic and the decorative, illustration in its widest sense as exemplified above is not always recognized. In its narrow sense illustration is less interpretation than the crystallization of a moment of import or excitement. This is the sense of the word to many laymen who gain their impression from the average illustrated novel or magazine of fiction, and this is an entirely modern development of the meaning of the word. What I wish to make clear is that if the Greek vase painter is to be called an illustrator, it must be in the larger and original sense of the word. The solution of the difficulty would perhaps be to find some better term to apply to both the vase painter and his work.

This paper is an attempt more exactly to define the work of the Greek vase painter, so as to arrive at a more just estimate of the value of his work in the pictorial or graphic sense of it.

Stress can not too often be laid on the fact that the Greek vase painters were never considered artists. Even their contemporaries ranked them as artisans. It is therefore in no sense fair to speak of the vase painters in any way that may lead to a confusion of their sphere with the major art. Dimly vase paintings may reflect the motives of the lost Greek frescoes, but the influence from mural painting upon pottery must necessarily be almost negligible. That is to say, a vase under socalled Polygnotan influence will prove the justness of the title by a certain tendency to elaboration, an indication of landscape, an attempt at perspective made by placing figures on different levels, and a certain subtlety in indicating characteristics not by attribute but by gesture and pose. Yet undeniably such treatment betrays both a lessening sense of the true function of vase painting and an overreaching ambition; and it is a presage of decadence.

The vase painter was primarily a decorator and a designer, whose sole function was to accentuate the beauty of the potter’s creation. What he drew or painted on the vase must necessarily be of such nature as to enhance the beauty of the curves and proportions of the vase. He must so decorate the surface as to increase the appreciation of the beauty of its form. Like the good accompanist in music, the vase painter must show his skill only to round out the aesthetic effect of two expressive mediums juxtaposed.

The designs of Greek vases are largely inspired by Greek mythology and legend. In the broadest sense of the word they are illustrations; but since they present scenes without a precise moment, scenes generally of undetermined locality, they may be said less to illustrate a story than to embody a theme. The Greek vase painter is not so much interested in the question of why and where Heracles had to struggle with the Nemean Lion as he is concerned with showing man directed by the powers above conquering the beast. The vase painter translated into terms of line and contour the stories which permeated the atmosphere. Very justly has it been said that Greek art flourished under peculiarly auspicious conditions. Greek poetry and Greek art ran side by side. Probably at no other time in the history of the world except as Greek art developed was it possible for artists and artisans, poets and populace to enjoy a common inspiration which engendered products of universal appeal. Not even in the age that saw the blossoming of Gothic art was there so unified an interest. Nowadays diversified interests as well as a stupid distinction set up between art and trade by the superficial minded make universal appeal well nigh impossible and art a mockery. The Greek realized fully that vital art is more than beauty; it is truth and utility and only therefore has it an excuse for being.

Museum Object Number: MS404

The golden age of Greek vase painting developed what one might almost term a pictographic system of decorating vases. A well known story was selected, perhaps one of the exploits of Heracles whose deeds, despite hackneyed treatment, never failed to win interest. Of this story the theme was taken and translated from words into lines. Just how this could be done can best be made clear by a study of some vases bearing mythological scenes.

The Greek vases in the University Museum with mythological scenes, though few in number, are fortunately varied in subject. Many of their themes are taken from the epic cycle, and include the wrestling of Peleus and Thetis, the Judgment of Paris, the ambush for Troilus at the fountain, the rescue of the corpse of Achilles, the fight over the body of Antilochus, as well as the peculiarly Attic themes of Theseus and the Minotaur, the exploits of Heracles, the Birth of Athena, and her Reception into Olympos. We should include also the symbolic theme of Greeks fighting Amazons, which is to be distinguished from the mythical combat of Heracles with Amazons, and seems to be in the fifth century at least an allegorical expression of joy and thanksgiving at the victory over the invading Persians in 480 B. C. Ultimately it may signify the downfall of matriarchy.

In general one may say that there are four ways of depicting a story—the simple, the complex, the complicated and the simplified.

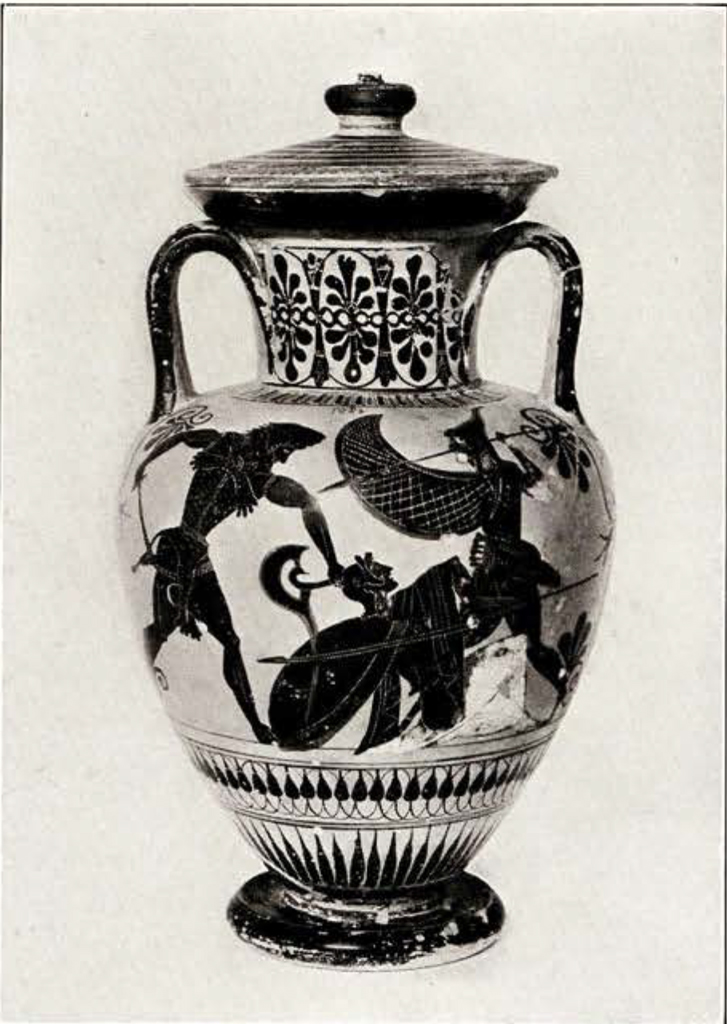

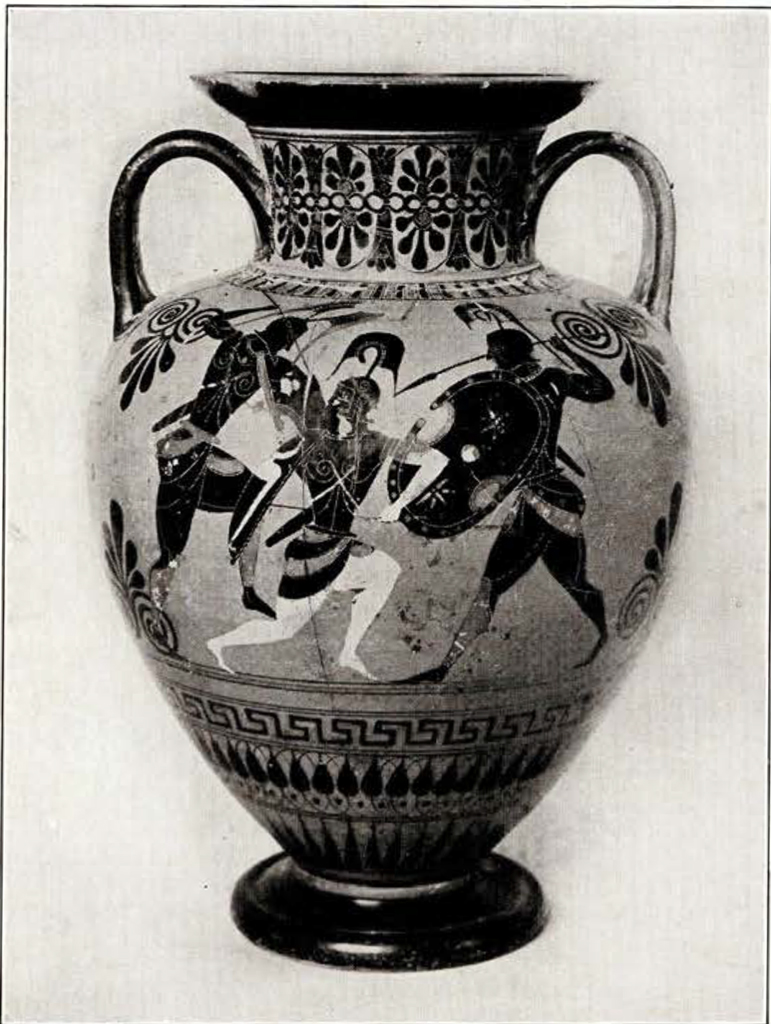

The simple treatment gives a scene whose meaning is obvious. The figures delineated are, even in the barest conception of the theme vitally concerned in the action, and none of the figures is superfluous. Examples of this simple treatment may be found on two amphorae in the University Museum (Mediterranean Section, Case VIII, No. 119 and No. 127). The obverse of each of these vases shows Heracles fighting Amazons (Fig. 29). In each picture Heracles has worsted one Amazon, and a second rushes to the rescue of the fallen. It would perhaps be stretching the imagination too much to find in the fallen Amazon the figure of the queen Hippolyta, whose girdle Heracles had to fetch for Eurystheus.

The complex method is represented by a blackfigured cylix showing the rape of Thetis. On the outside of the cup in the centre of each field Peleus struggles with Thetis. On each side of the straining group stands a Nereid, sister to Thetis, an affrighted witness of the scene. Thus to the simple fact of the wrestling is added the note of general distress caused by the violence of the intruder. Another example of the complex method of treatment is seen on the vases representing Heracles’ conquest of the Nemean Lion. This takes place generally in the presence of Athena, the patron deity of the hero. Frequently his nephew and comrade Iolaos is a spectator. Almost always the hero’s arms—his bow, quiver and club—are held by these spectators, or are hung up in the background, by way of indicating that weapons are useless against the invulnerable beast.

The third method I call complicated because it introduces figures which are not really germane to the scene, although they do belong in the story. For an example of this method I have chosen a large blackfigured amphora from Orvieto, showing Theseus slaying the Minotaur. The story goes that Theseus, son of Aegeus, king of Athens, along with six youths and seven maidens, was sent to Crete as part of the tribute exacted by the Knossian sea king from the subject city of Athens. These young people were to be victims of the Minotaur, the bull of Minos, which in historical times was misunderstood as a half animal, half human monster, instead of the sacred bull baited by toreadors as he is still in Spain. Theseus resolved to slay the Minotaur so that never again such tribute need be paid. There was however a great difficulty about the accomplishment of this ambition, for the monster was kept in a labyrinth or maze from which egress was practically impossible. Theseus won the confidence of Ariadne, the daughter of Minos, who gave him a key to the labyrinth, she supplied a great quantity of yarn or string, one end of which Theseus tied to his person. Then he went in stealthily by night to the monster’s lair while Ariadne stood outside the building paying out the string. When he had slain the Minotaur, Theseus simply followed back on the course of the string to the entrance where Ariadne awaited him.

Museum Object Number: MS5467

Now mark how the vase painter tells the story. In the centre of the panel stands Theseus dispatching the bullheaded man. This deed should be done in a secret place unseen of men; but at the left behind Theseus is Ariadne, and behind her stands a draped man who, if bearded, might on the analogy of other representations of the scene be her father Minos whom she is betraying. At the right of the central group are three figures which may be Athenian youths. In an illustration none of these five figures has any proper place, but in a story telling picture they serve to round out the theme of the narrative. The figure of Ariadne suggests the way by which Theseus attained his goal; the figure which normally stands behind her, Minos, locates the action in Knossos, and suggests the complication of forces that caused Ariadne to aid the stranger despite her natural inclination to do her father’s will; the three figures at the right suggests the mission on which Theseus was sent to Crete, and also the result of his daring—the freeing of the Athenians from the galling tribute.

The fourth method consists in taking a well known story telling motive or type and using it less with the idea of telling a story than of decorating a space. A blackfigured cylix shows on the exterior on one side between eyes a nude youth and a seated sphinx. The sphinx is a hybrid creature commonly associated with Egypt, but the winged variety is of Mesopotamian origin. The Asiatic form was adopted by the Greeks in the period of strong artistic influence from the East, and was used as decoration on the Oriental-izing pottery of the seventh century B. C. In Greek literature and mythology the sphinx has only local connotation—Thebes, a city which has much of the non-Hellenic in its makeup and traditions. The sphinx is involved in the most famous legend of Thebes, the story of Oedipus, the most cursed of men, who unwittingly slew his father and married his own mother. The story goes that Laius, king of Thebes, being warned by an oracle that his son begotten against the will of the gods should slay him, had the baby exposed. But shepherds found the child and reared him, calling him Oedipus —swellfoot—from the fact that when he was found his feet were pierced and bound together. The lad one day in a traveller’s brawl on the highway slew his unknown father; later he came upon the sphinx. The sphinx had been plaguing the country about Thebes by killing all she met, for none could save his life by guessing the answer to the riddle she asked. It ran to this effect—There is upon earth a two footed and four footed one voiced thing that is also three footed; it alone of all creatures of earth and sky and sea changes its nature; when it goes on most feet it is feeblest. Oedipus read this riddle by Man, who in babyhood creeps on all fours, in his prime walks upright and in old age leans on a staff. Having so answered the sphinx, he dispatched the monster, and the grateful Thebans made him their king and gave him to wife their queen Jocasta, widow of Laius.

In Greek art a man and a sphinx in a group seem always to connote Oedipus, but there is little in this representation to clinch the allusion. The youth has none of the travellers’ accouterments which tradition gives to Oedipus in this motive. The motive is become mere decoration.

Since Greek decoration like all good decoration is derived, it is not fanciful to look for stories behind such scenes of blackfigured vases as the chariot scene, or the warriors playing dice, and other scenes of which we do not know the full significance. Some day we may discover the exact meaning of such scenes. It is not so long since the chance discovery of some verses of Bacchylides made clear the scene of Dionysos sailing on the famous cylix of Execias.

We must realize then that the story telling of the Greek vase painter is of a very special sort. Its essence is compactness. Details of his picture suggest details of the story behind it: a tree, for instance, will serve as short hand symbolism for a forest. This compactness must reveal how far the Greek artist is removed from the primitive. Primitive narration placed side by side successive scenes each with the hero therein. Such was the sculptor’s method when he carved on the metopes of a Doric temple the exploits of Heracles or Theseus. Except for the famous cup in the British Museum on which Duris painted exploits of Theseus, the vase painter did not employ continuous narrative. Very rarely do both obverse and reverse of a vase feature the same story. The rule is that the obverse is the more important, and that the reverse is a decorative foil to it. The reverse may be related to the obverse, or it may be quite distinct from it. For instance the two amphorae mentioned above as having on their obverse the scene of Heracles and the Amazons, are decorated on their reverse with kindred scenes—one with mounted Amazons, the other with Greeks fighting Amazons; but the amphora showing Theseus and the Minotaur has on the reverse a simple scene of the departure of a warrior in his quadriga.

This brief sketch does not take into account scenes of every day life, which are very common on Greek vases, and which in their glimpses of palaestra, banquet hall and ceremonial, are more nearly illustrations than are the mythological scenes just discussed. The paper contributes little new to the appreciation of Greek vases, but it constitutes the beginning of a larger study of the narrative element in Greek art, and if it help at all to increase the layman’s interest in the Greek vases in the University Museum or in Greek vases in general, it will have served its purpose well.

E. F. R.