The origin and development of symbolism, letters, and designs used in decoration either with or without symbolic meaning is a field of investigation that can never be exhausted. The derivation of a symbol may be directly indicated by its form and may be very simple and obvious, or its origin may be quite different from what it seems. Again, a symbol may migrate form one people to another or from island to island or from continent to continent, modifying its form and taking on new meanings for the confusion of anyone who would trace its migrations. Perhaps the most perplexing thing about such devices is an extraordinary habit they have of deriving themselves in identical forms from totally different objects in different parts of the world and getting themselves associated in each instance with similar ideas.

An example of one or the other of these two classes—migration or convergence—is furnished by the double axe of ancient Europe and the so-called bannerstone of ancient America.

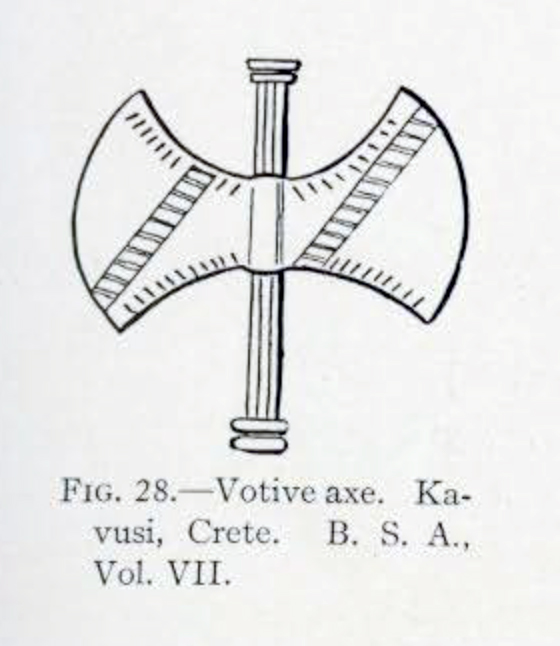

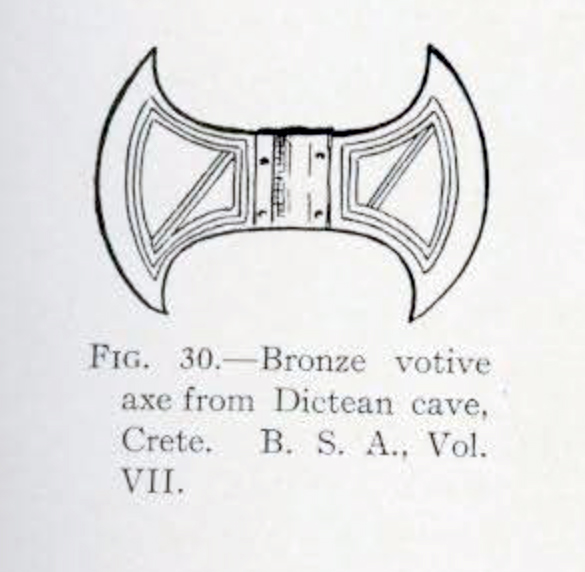

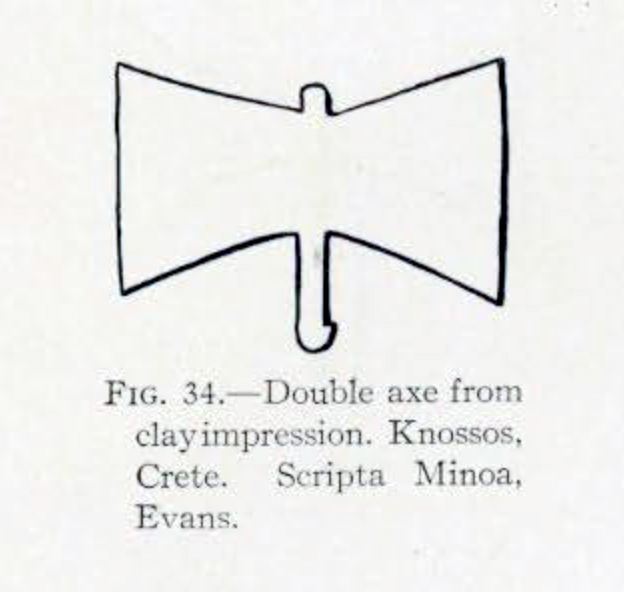

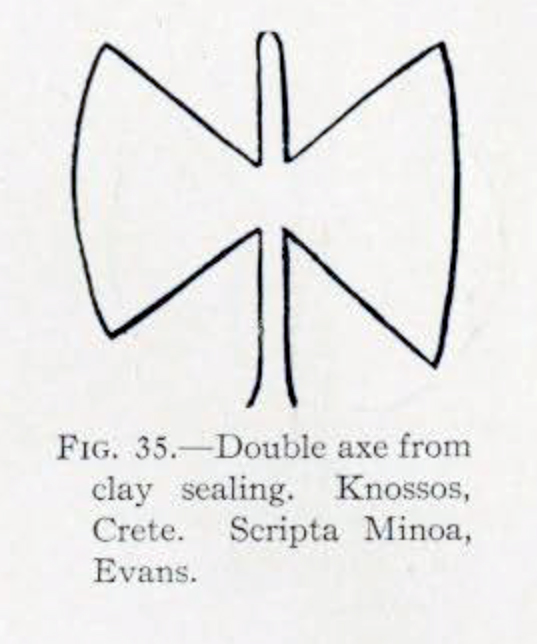

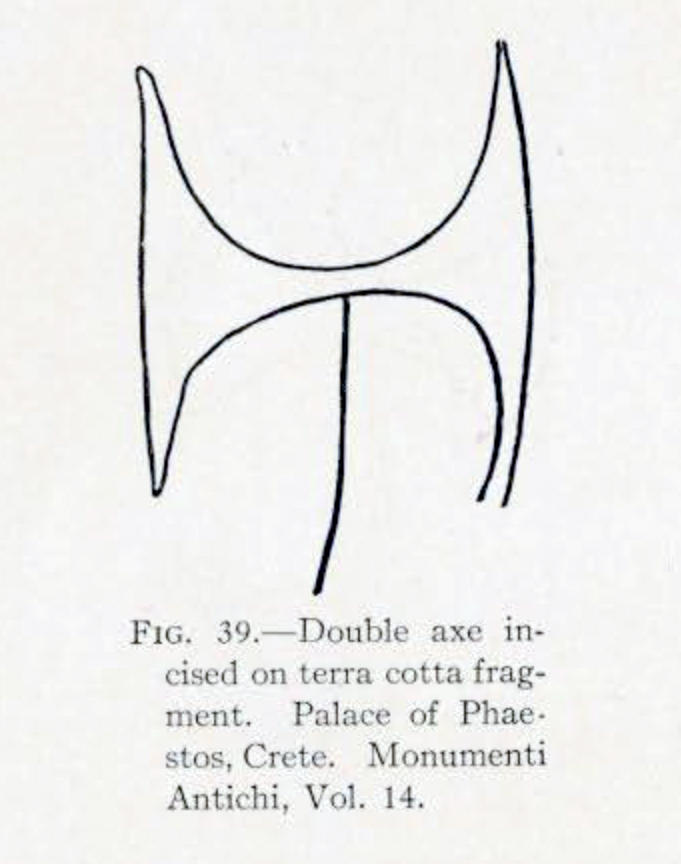

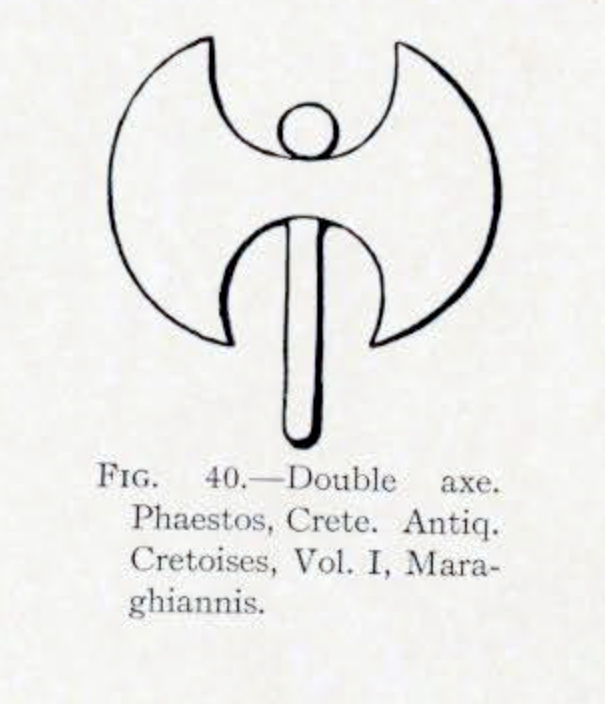

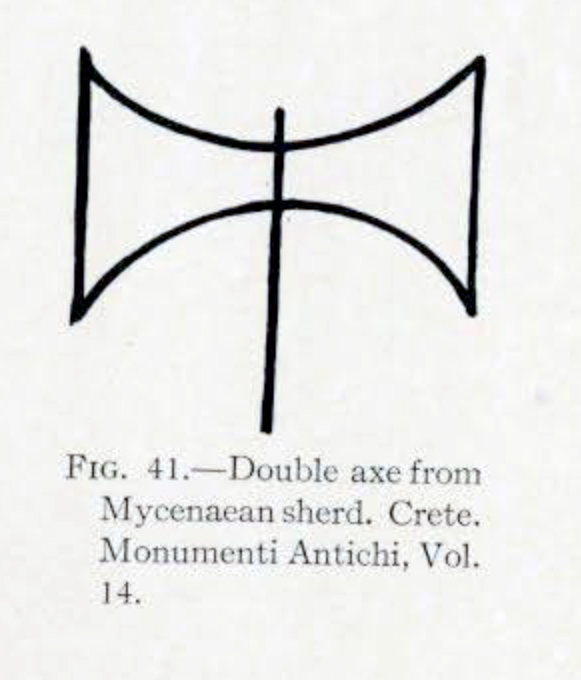

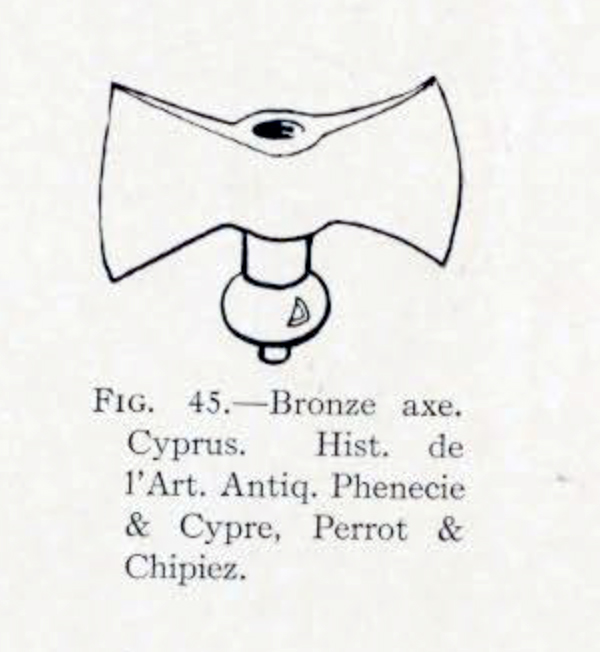

Double axes made of bronze and found in Crete are shown in the collections in the University Museum. Their date is about 1500 B. C. They appear to have been intended for use either as weapons or for hewing wood. The double axe of Crete made its appearance after the beginning of the Bronze Age. The stone axes of the period immediately preceding the Bronze Age are never double.

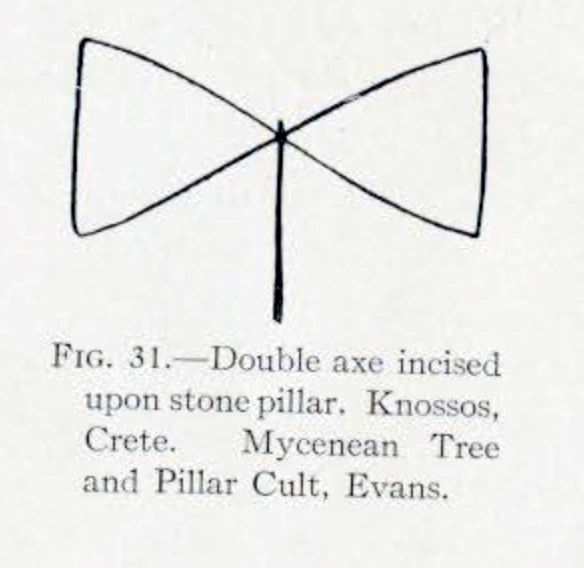

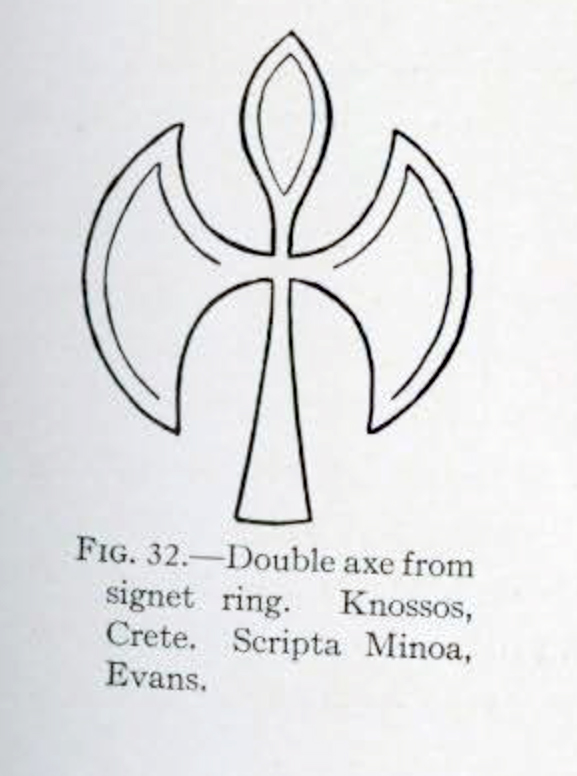

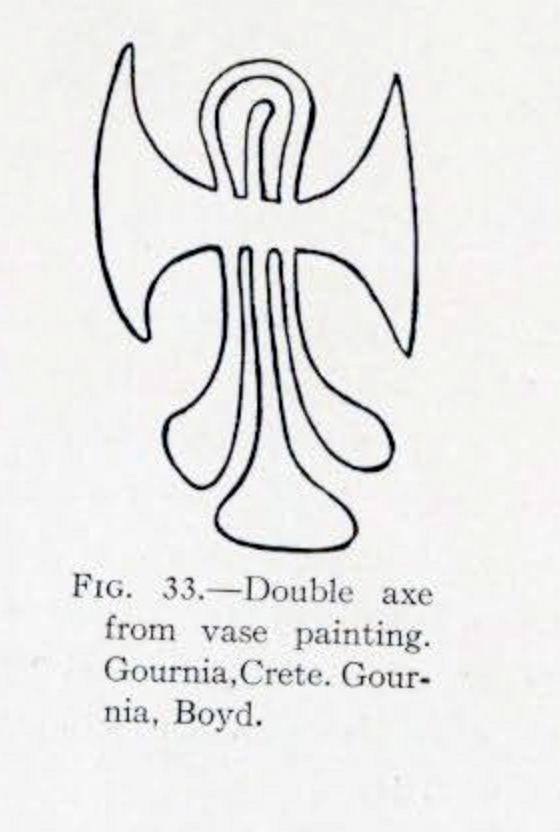

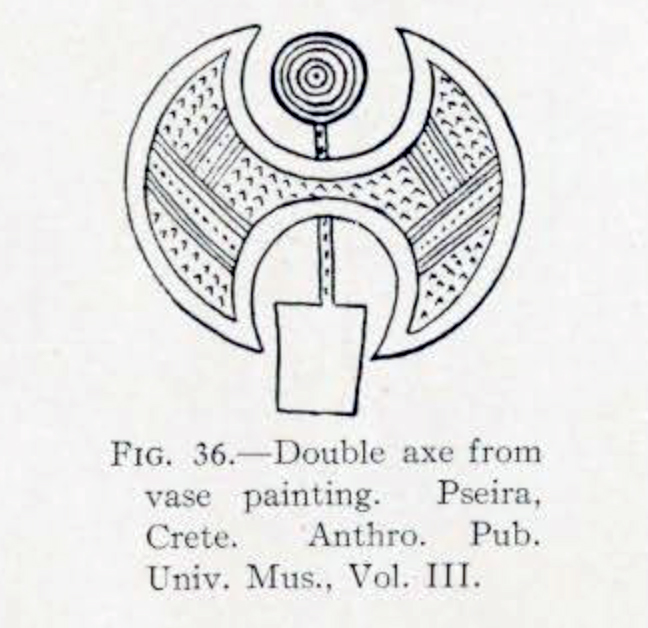

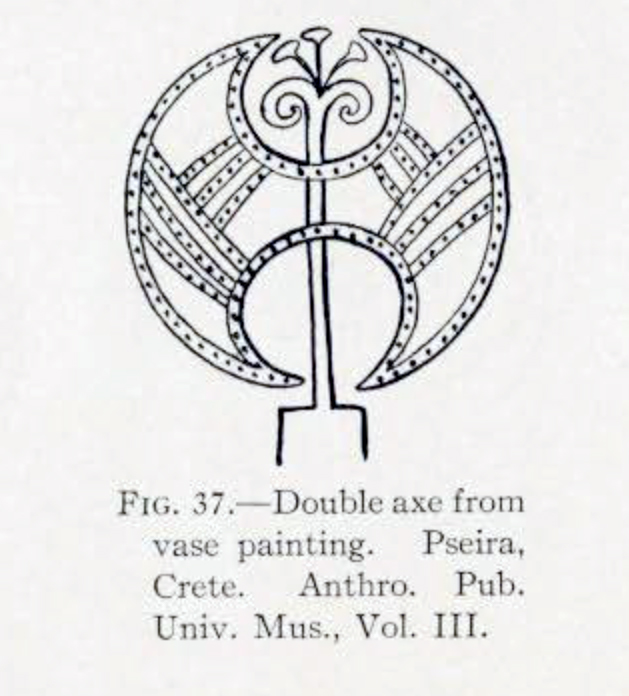

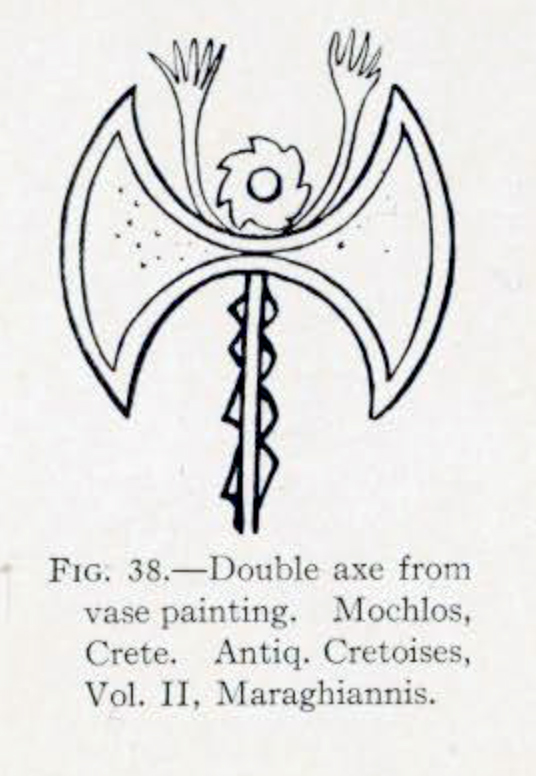

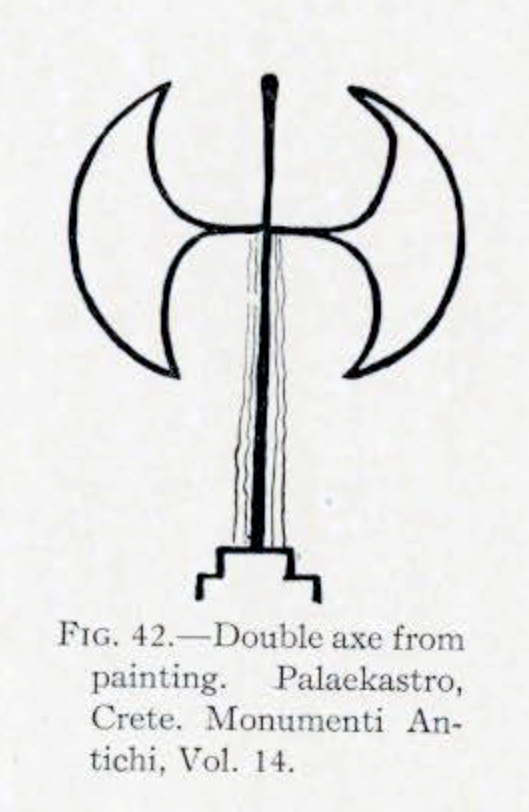

Besides the full sized axes made for use, there have been found in Crete of the Bronze Age, miniature axes of gold, bronze, ivory and clay. These are evidently symbolic ornaments and sometimes votive ‘ offerings. The outline of a double axe was found at Knossos on a clay sealing which Sir Arthur Evans assigns to the Middle Minoan I period. The well-known labyrinth or palace excavated by Evans at Knossos takes its name from the double axes carved in outline on its walls. The same design is painted frequently upon Late Minoan I pottery and engraved upon sealstones, and in all these cases the carving or painting has a symbolic significance. The natural inference is that the double axe in Crete was a sacred object and the symbol a cult.

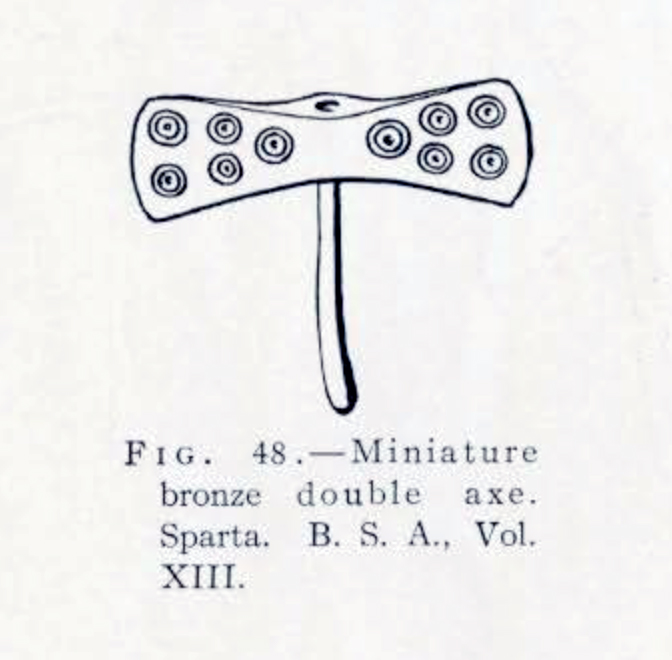

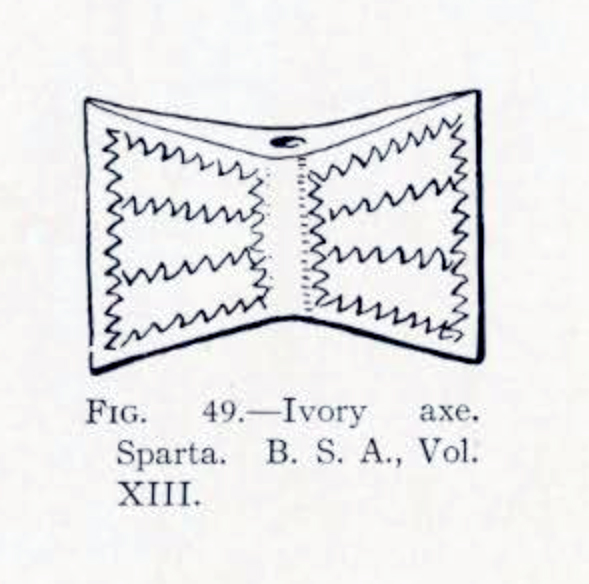

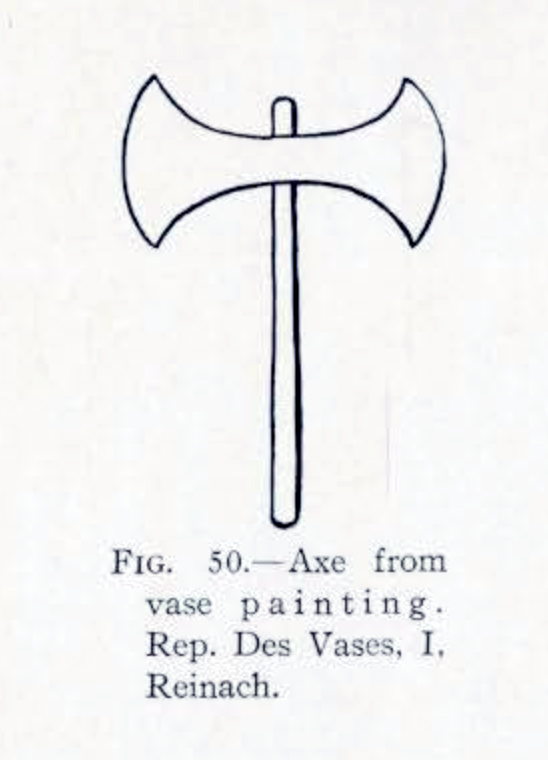

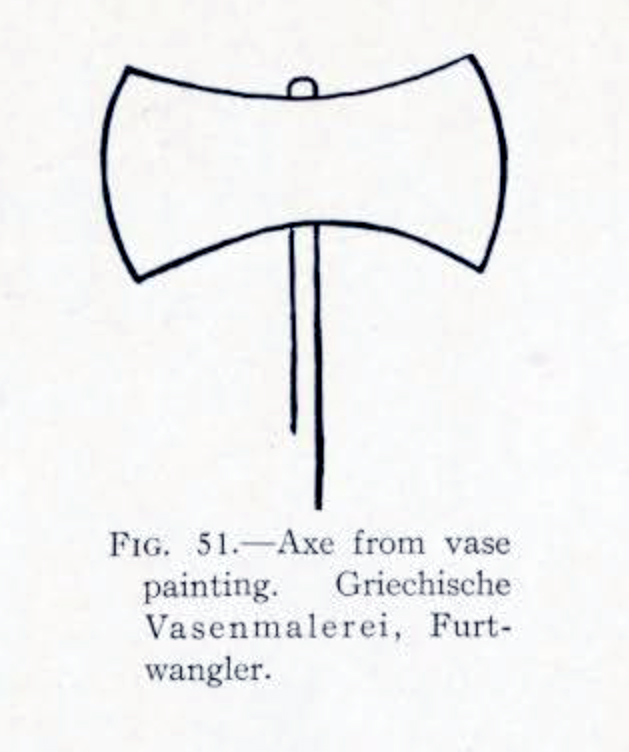

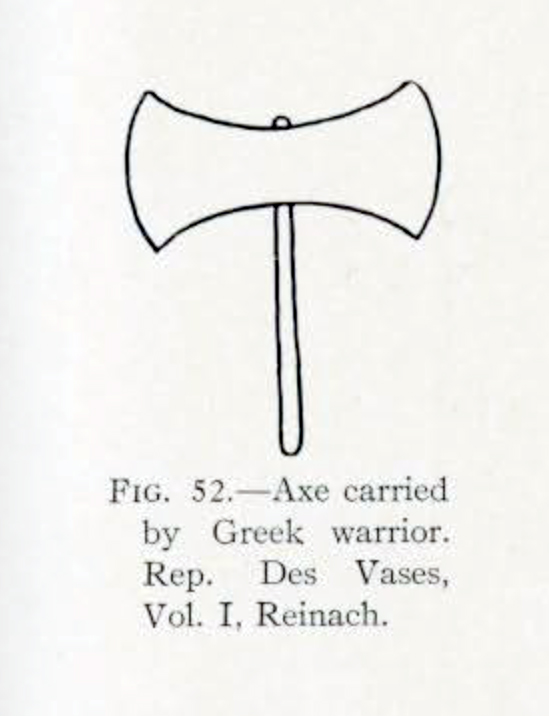

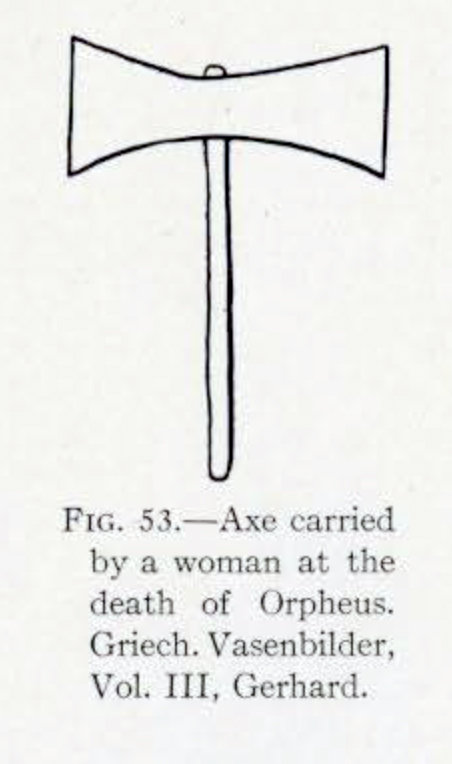

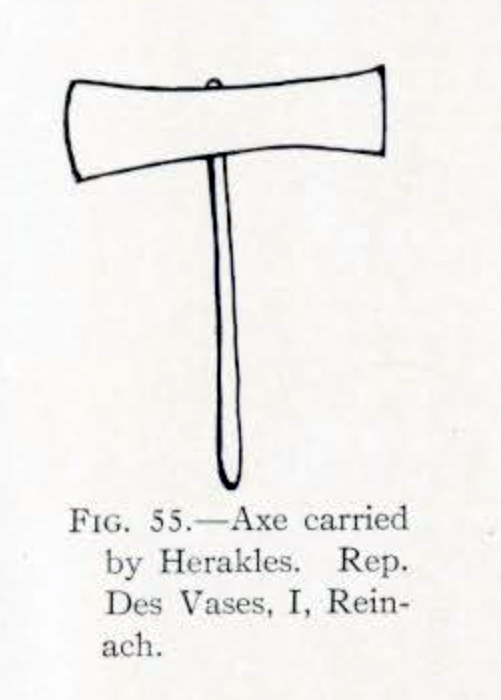

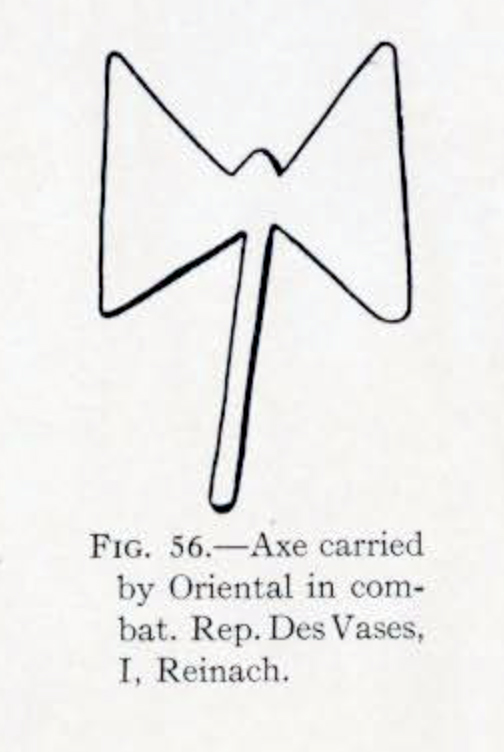

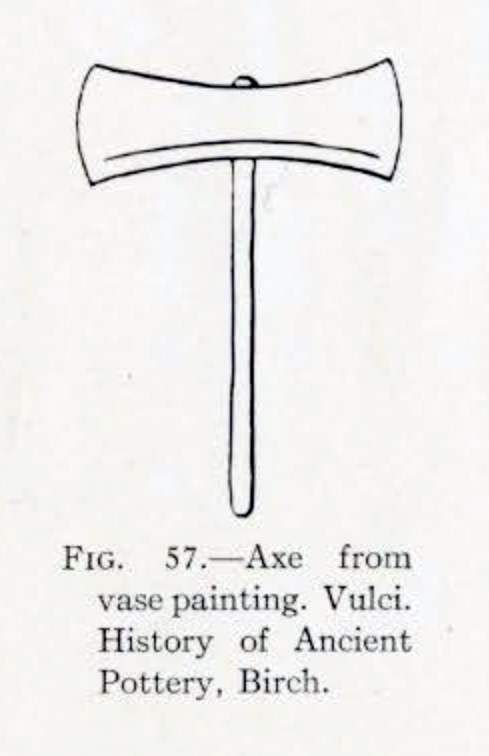

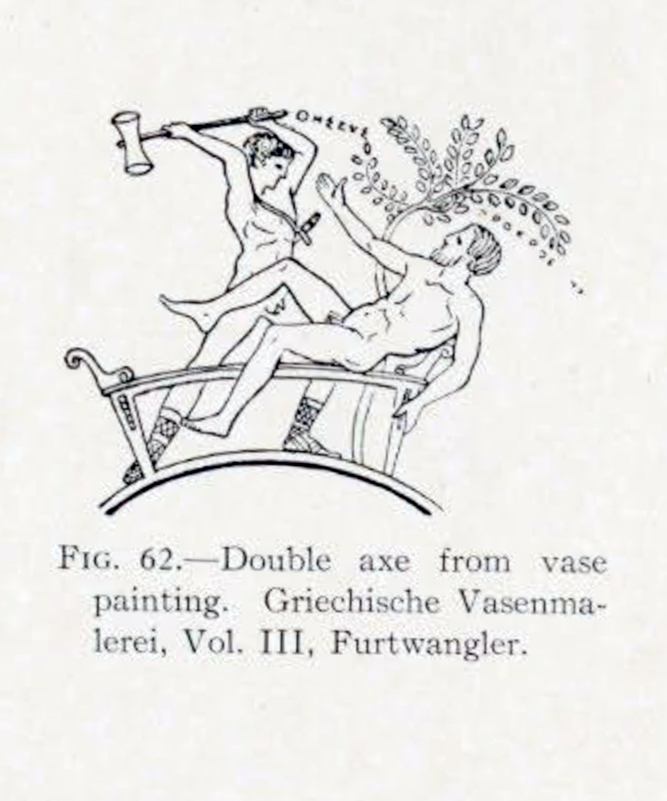

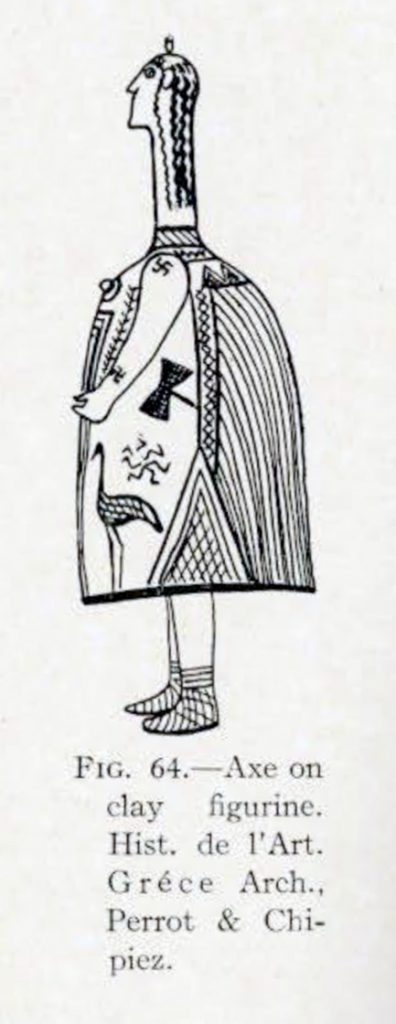

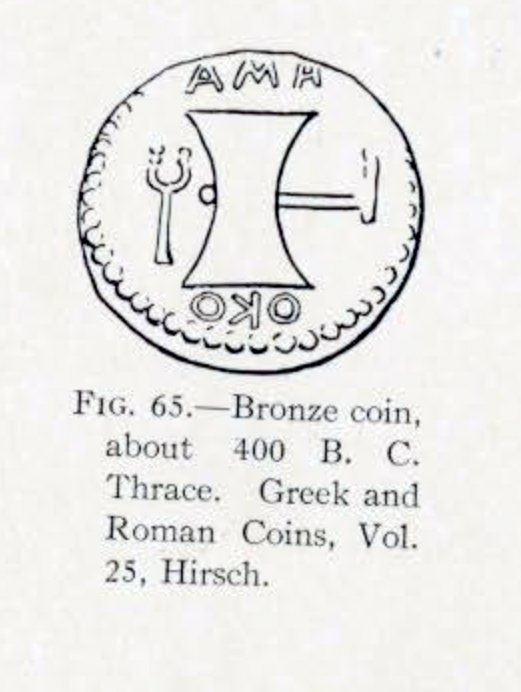

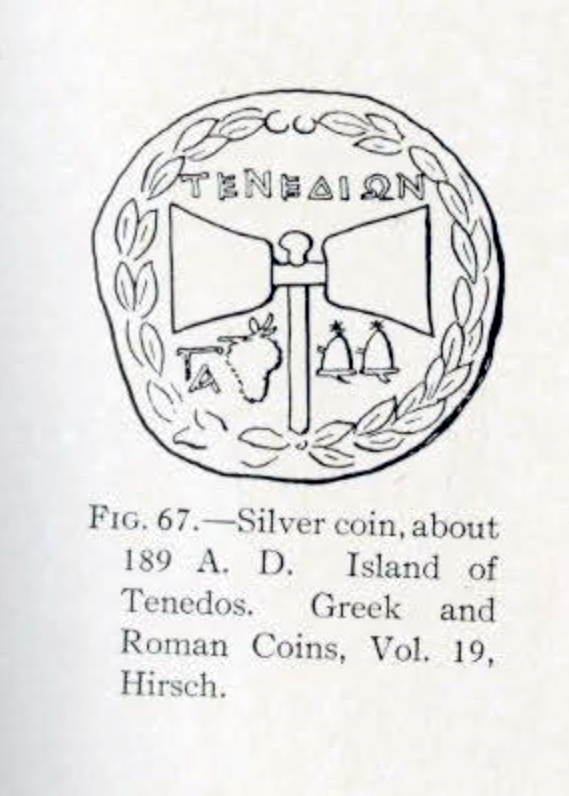

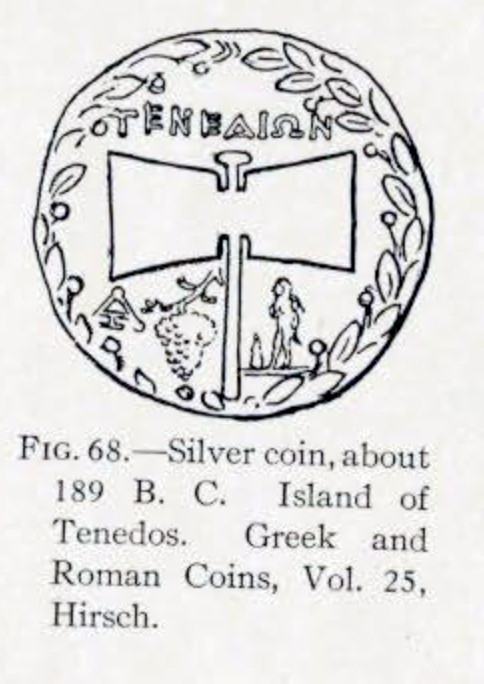

In Greece the symbolic use of the double axe is apparent from very early times. In Sparta, numerous miniature axes in ivory or in bronze have been found dating from a period as early as 800 B.C. It appears in painted outline upon Dipylon vases and is frequently represented on red-figured and black-figured vase paintings of the Classic period where it is sometimes seen in the hands of various persons portrayed in the decorations. Small double axes of gold were worn by Greek women and are found in their graves. It is also shown on various Greek coins.

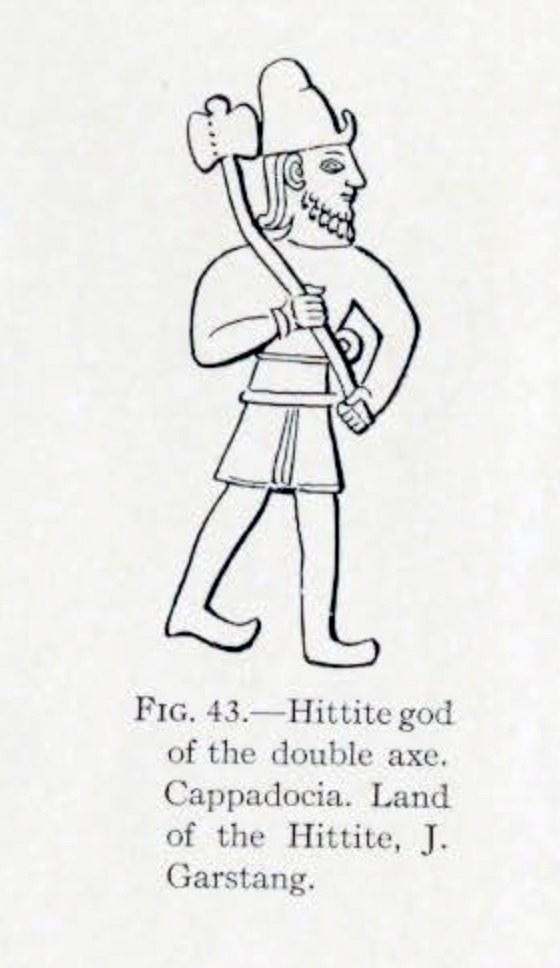

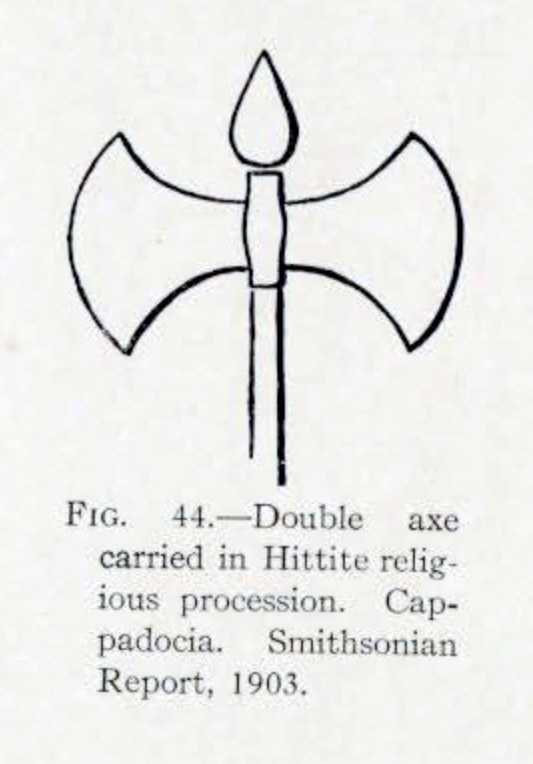

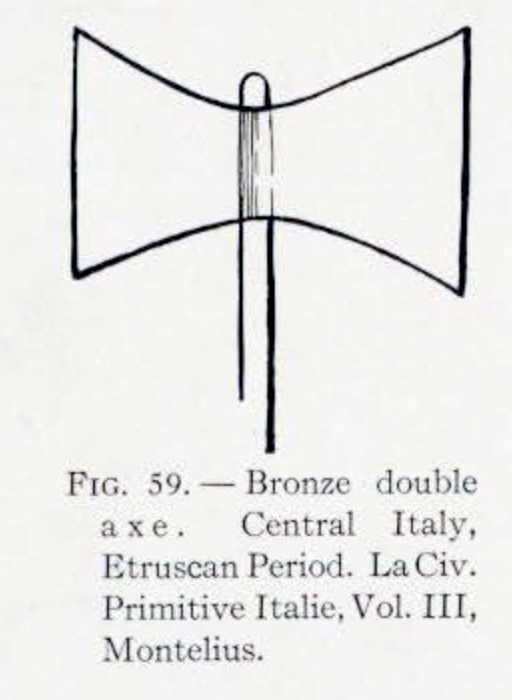

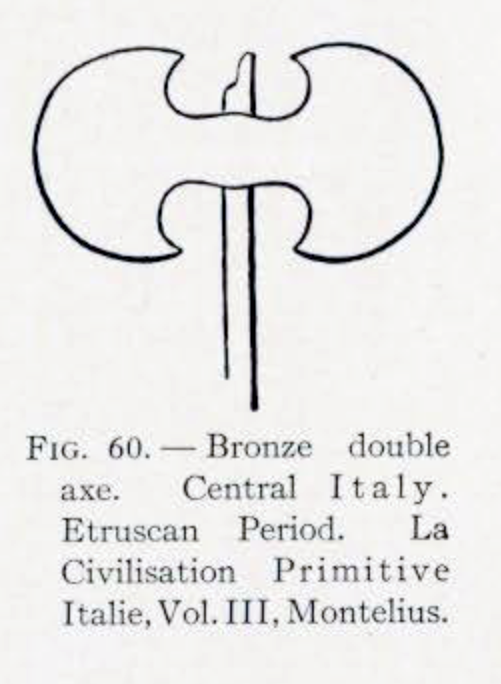

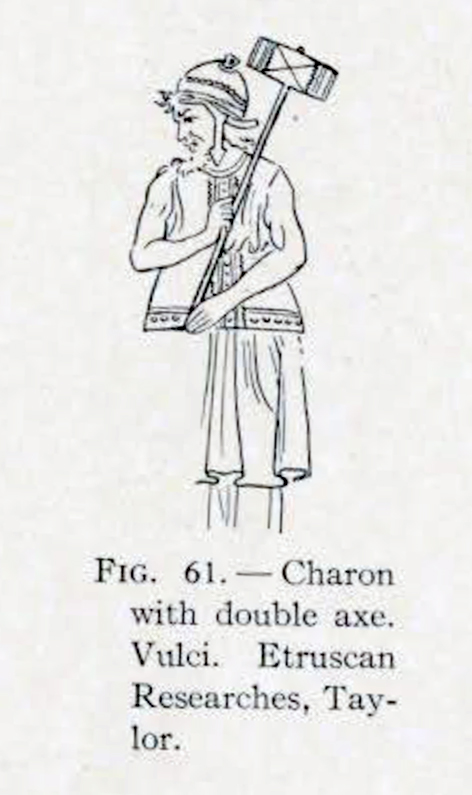

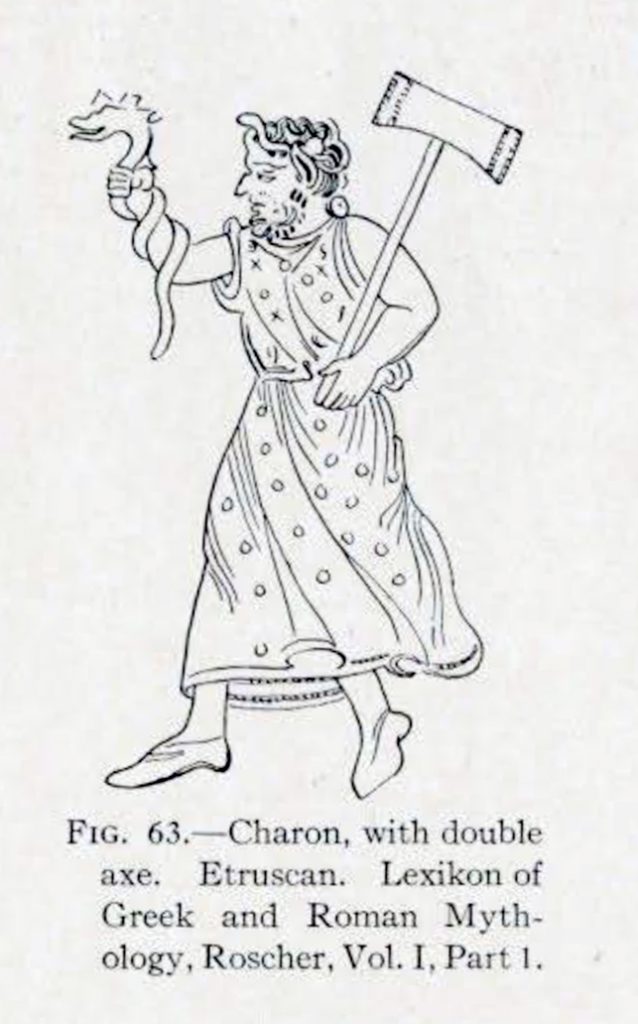

A double axe appears among the Hittite remains of Syria and Cappadocia where its use was evidently symbolic. It is found in Asia Minor and among the early Etruscan remains in Italy.

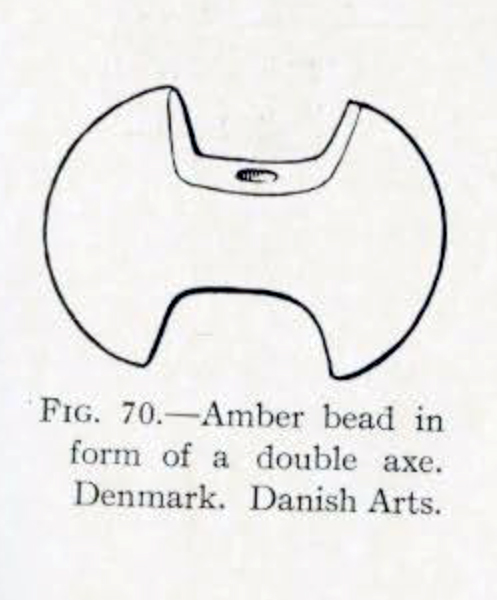

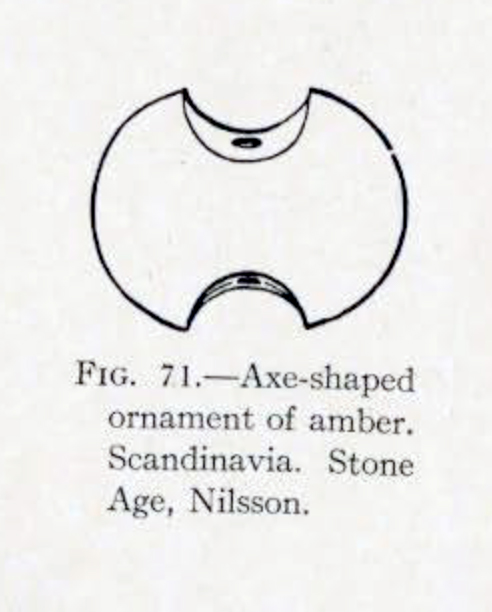

Scandinavia had double axes of stone in the Stone Age, evidently meant for use. During the same Stone Age, miniature double axes in the form of amber beads or ornaments were also in use.

The stone axes with two cutting edges that are sometimes found in Great Britain, appear to be a local development from the single axe and are less like the double axes of the Mediterranean than are the Scandinavian double stone axes.

From the evidence of archaeology, therefore, the use of the double axe either as a weapon or as an implement for domestic use or as a symbol or as all three was very general in countries around the Mediterranean during very early times. All the examples known, however, belong in the Bronze Age. In Scandinavia they are found in the late Stone Age, which, however, was contemporaneous with the Bronze Age in the Mediterranean area.

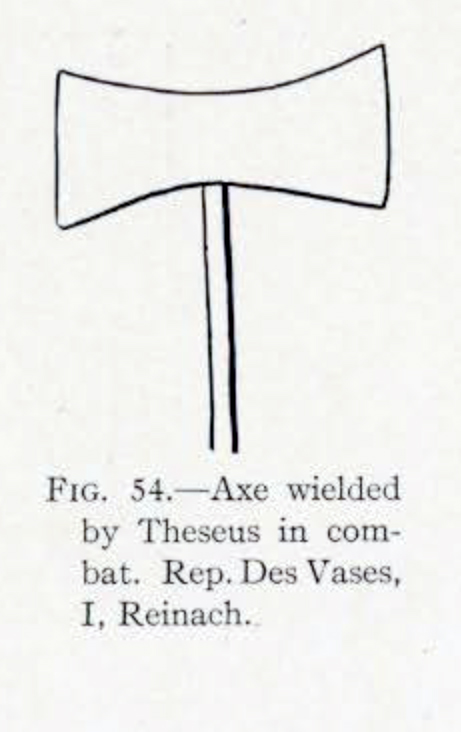

In all the countries mentioned, the tendency of the double axe is to become associated with ceremonial uses, if indeed it did not begin with these associations. It was everywhere a sacred object and its use was symbolic. It is true that it is sometimes represented as a weapon, as in the exploits of Theseus on a red-figured kylix in the British Museum or in the hands of the Amazons, as on a frieze at Magnesia in Asia Minor, and also on vase paintings. This occurrence of the double axe, however, as a battle axe used by the heroes of mythology is in no way inconsistent with its sacred attributes or its essentially ceremonial or symbolic character.

The fact that it is sometimes seen in the hands of Amazons led Nilsson to call the double axe “The Amazon Axe.” There appears to be no warrant for this name. Nilsson is wrong in his statement that this is the weapon peculiar to the Amazons and that they are always armed with double axes. An examination of the vase paintings shows that Amazons are armed with other weapons quite as often as with the double axe.

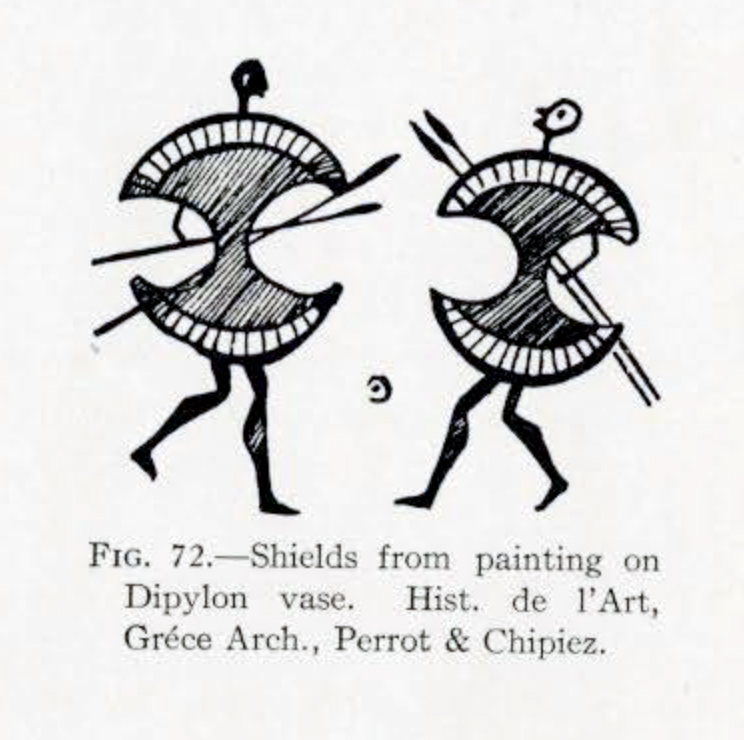

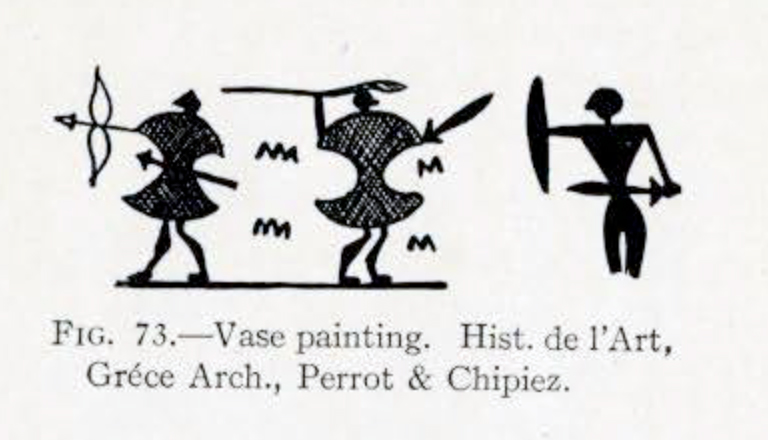

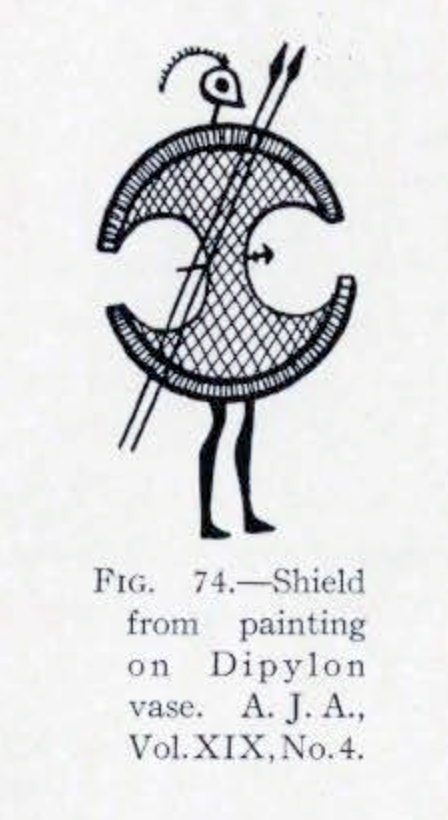

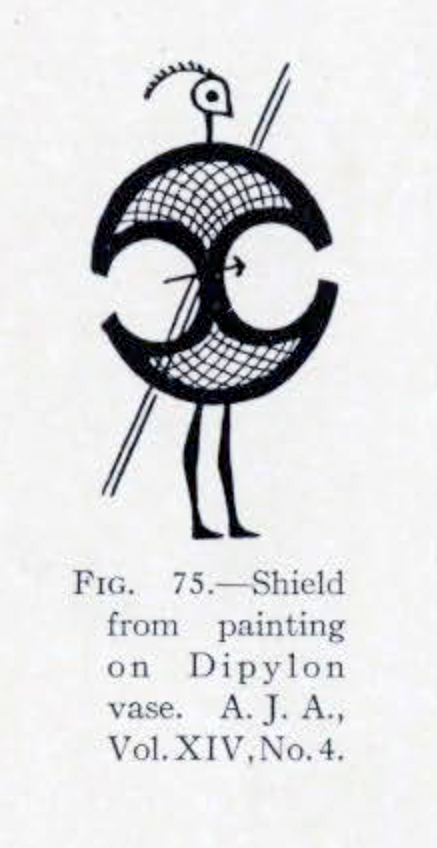

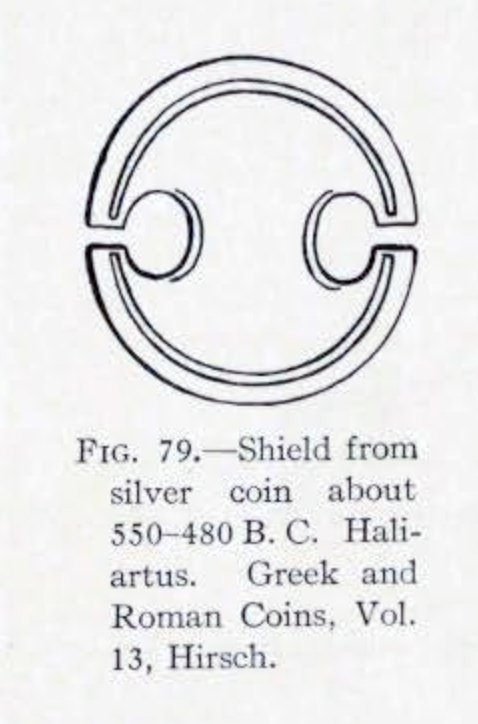

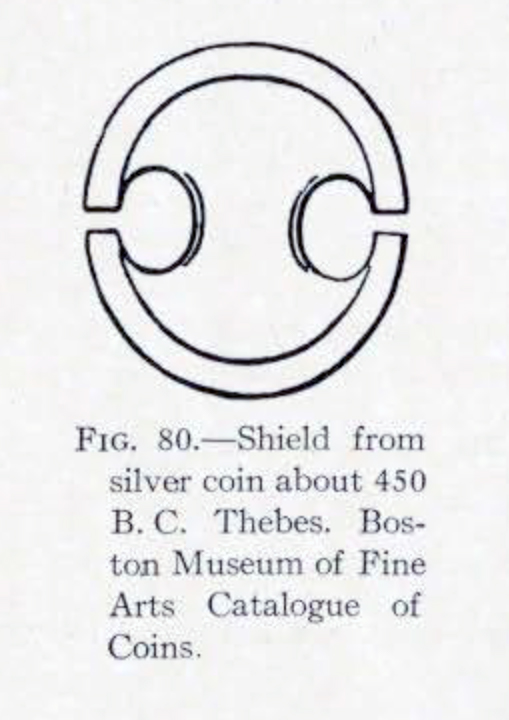

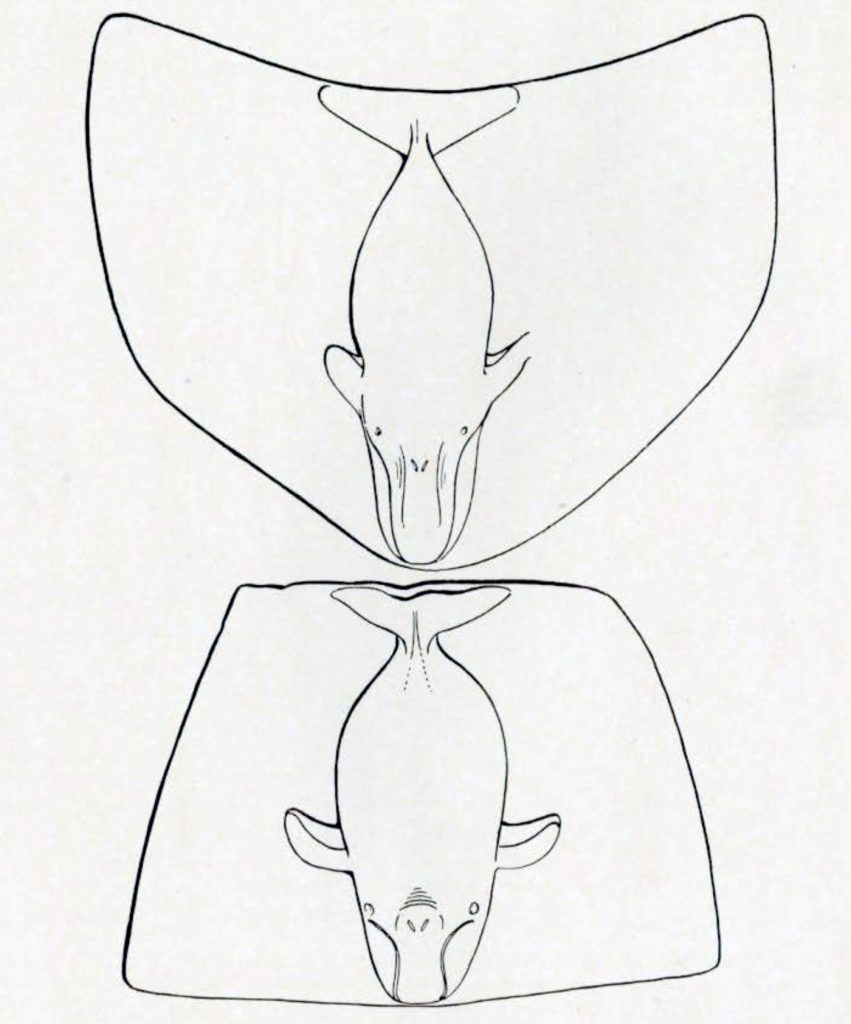

An Archaic Greek Shield

There appears to be a close connection between a certain form of Greek shield and the double axe. In the Archaic period in Greece this shield is shown in paintings on Dipylon vases, where it is carried by warriors. On the same pottery the symbol of the double axe plays a prominent part. It is hard to see why a shield of this shape was adopted unless it was in imitation of the outline of the double axe. It is quite intelligible that such a symbol might have been adapted to the form of a shield. If the double axe was a sacred object or a symbol of strength, or if its symbolism was that of protection, a shield of this form would naturally have more virtue than an ordinary shield. A similar form of shield, known as the Boeotian, is seen on Attic vase paintings and on Greek coins dating from the sixth century B.C. to the second century B.C.

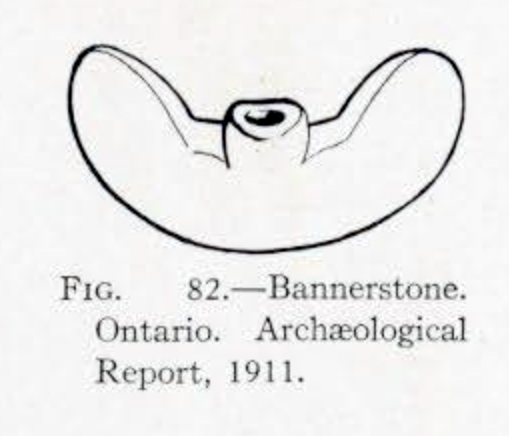

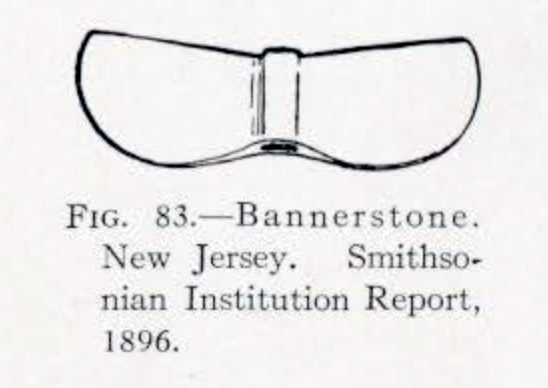

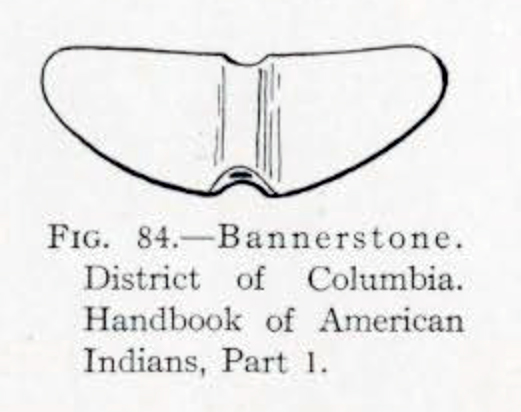

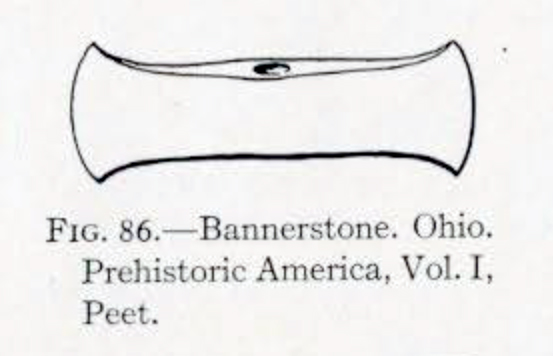

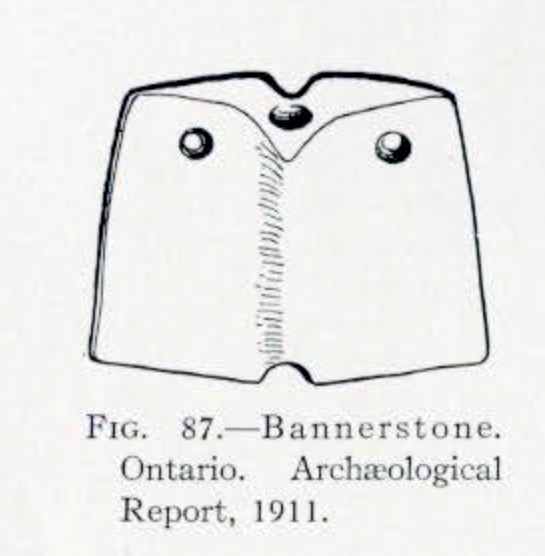

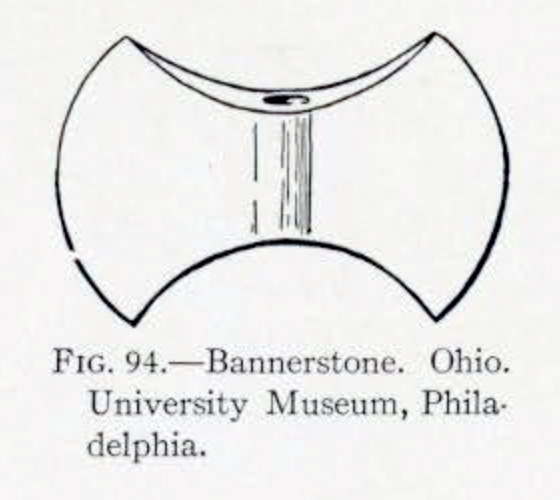

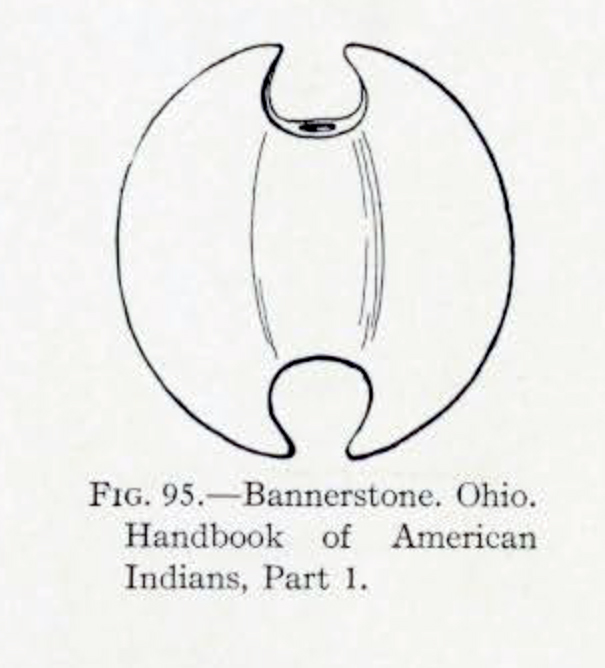

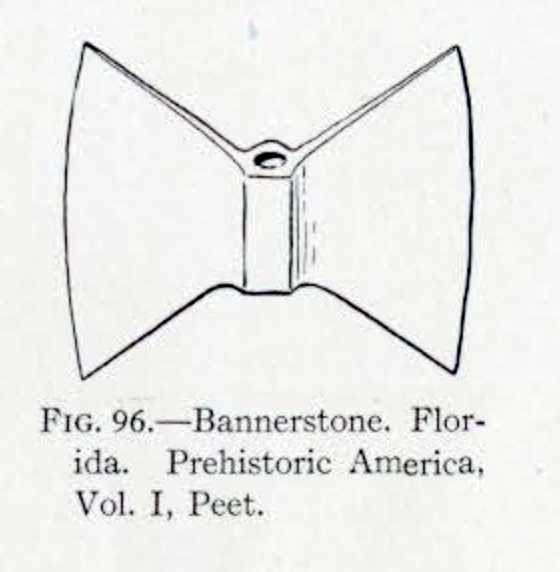

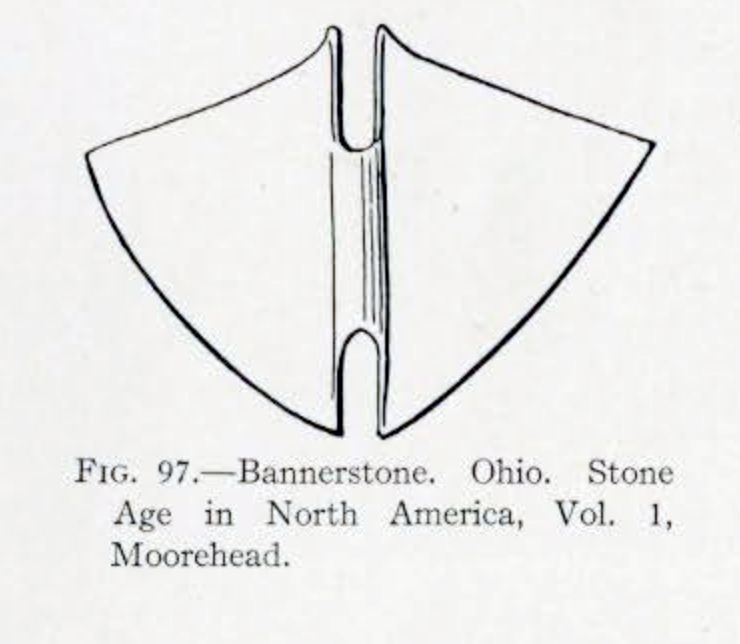

The Bannerstone

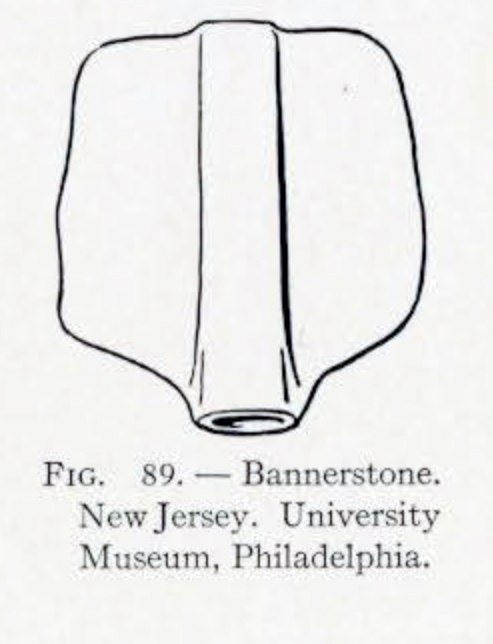

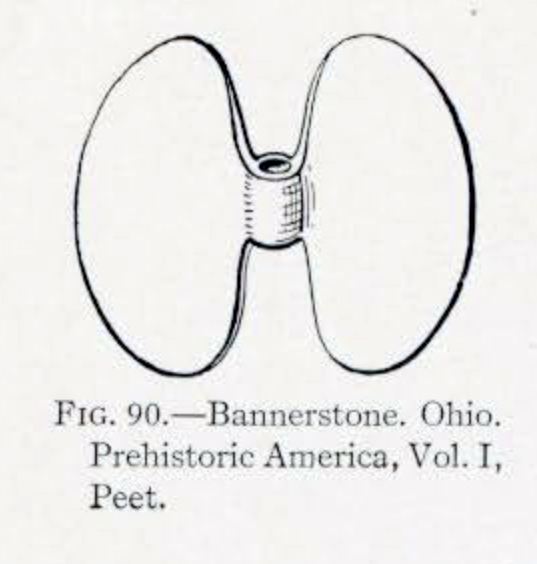

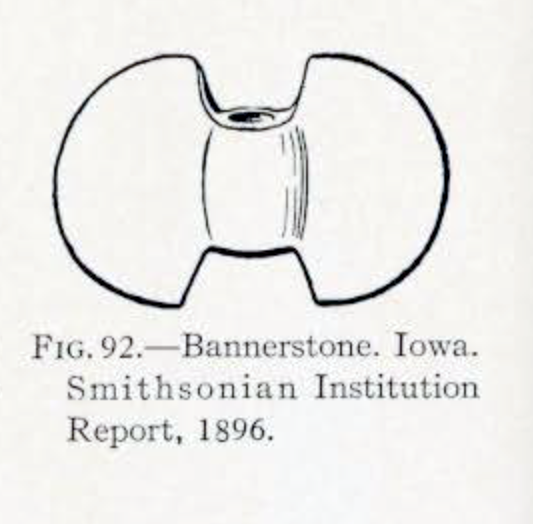

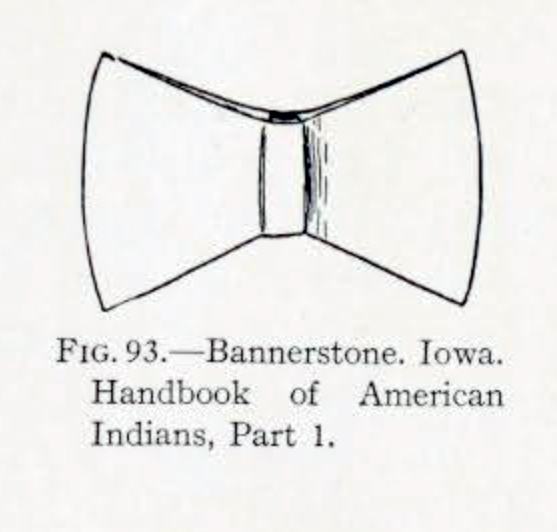

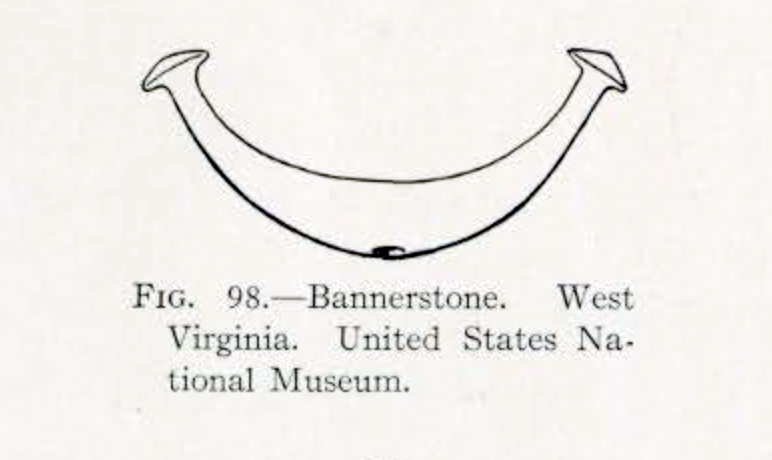

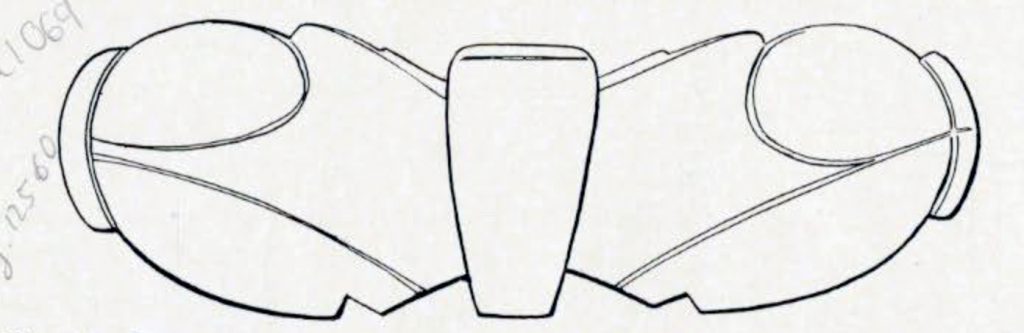

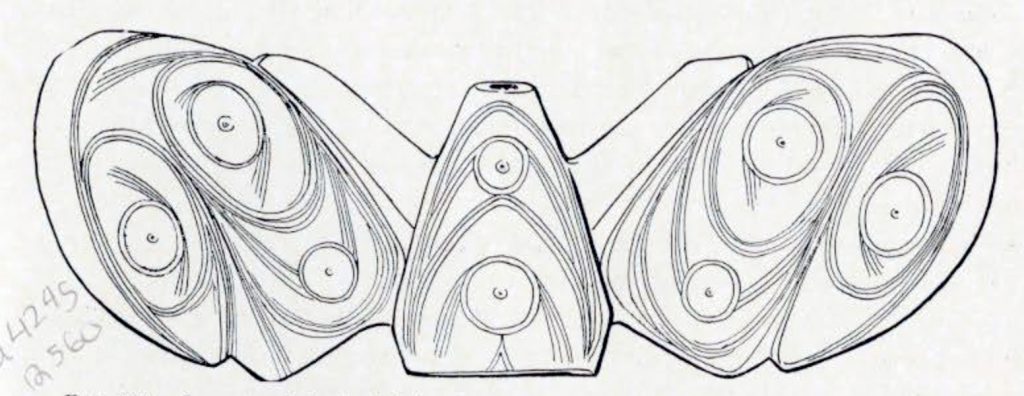

The class of objects to which this name has been applied by common consent is found in many different forms and made of a great variety of stones. It is an ancient thing used by the former inhabitants of North America. It is usually bored through the center as if for mounting on a staff, but is sometimes found without the bore.

Prof. W. H. Holmes, Director of the United States National Museum, has been kind enough to let me see the manuscript of his forthcoming book on American Antiquities and to give me his permission to quote from it the following passage.

“Within the same region in northeast America, the thinning out as does the gouge to the south and west, is an object of rare and highly specialized form, an axe-like implement, known as the bannerstone, with tubular perforation for hafting and with extremely varied wing-like blades. It is not found elsewhere in America. In northern Europe there is found a drilled axe of similar type and it is a noteworthy fact that this form of artifact throughout the Old World though originally perhaps a thing of use had wide and diversified application as a symbol. The following very interesting and suggestive statement regarding the ‘Amazon Axe’ is quoted from Nilsson. ‘Stone weapons of this kind are rather variable, and the central part is often much shorter than the figure here referred to, resembling that shown in Fig. 174. The original of this sketch is from the south of Scania, and is preserved in my collection, but is not finished, there being no hole for the handle—but this weapon is always known by both ends being much more expanded and more or less sharpened. It is exactly like the axes with which the Amazons are armed, wherever we see them represented. On a marble sarcophagus of the Louvre, at Paris, bearing the inscription SARCOPHAGE TROUVE A SALONIQUE EN MACEDOINE, the warriors wield axes with one edge and a pointed sharp back: but all the Amazons have such two-edged axes as the one here sketched. The Amazons are represented with such axes even in other places also; for instance, on some antique friezes in the British Museum. In a treatise on The Sword of Tiberius (in German, 4to, with coloured engravings), an Amazon is also represented with a similar axe. It is called Amazon Axe. Xenophon mentioned it in the Anabasis, iv, 4; and Horace speaks of Amazonia Securis in the Odes, iv, 4, 20.’*1

“The American homologue certainly had no other than sacred and ceremonial functions. It may not be amiss to suggest that possibly in prehistoric times examples of this type of implement were carried by some voyager across the intervening seas and that being regarded by the natives as possessed of supernatural attributes these were adopted as ‘great medicine’ spreading to many tribes and taking a wide range of form. It does not appear an entirely impossibility that a stone or bronze perforated axe of this type left by one of the Ericsson ships should have been the ancestor of these peculiar objects. Who will venture to say that these greatly varied, beautifully finished and widely distributed objects may not have come into existence among the tribes during the 620 years separating the discovery of Vineland and the arrival of the pilgrims.”

In the passage which I have just quoted from his forthcoming book, Dr. Holmes suggests that the bannerstones were derived from the European double axe, one of which may have been brought over either by Ericsson or by some unknown voyager in prehistoric times, and afterwards copied by the Indians for their own uses. Dr. Holmes puts forward the general proposition that these objects may have come into existence among the Indians during the 620 years separating the discovery of Vineland and the arrival of the pilgrims.

In order to accept or reject such a view it is necessary either to support it by strong positive evidence or oppose it by strong negative evidence. That an object identical in form with some of the banner-stones existed in Europe on the shores of the Mediterranean and on the shores of the Baltic in times very much earlier than that of the Norse explorers is certain. On the other hand, there is no evidence at all that it was in use or even known in any part of Europe during the period between the discovery of Vineland and the arrival of the pilgrims.

In the Mediterranean area the double axe belongs in the Bronze Age and in Northern Europe it is confined to the Stone Age. It is not probable that Ericsson or any of his contemporaries would have brought to America an implement or symbol that was not in use in their time. On the other hand, there is evidence that the banner-stone existed in America at a very much earlier time than that of the Norse voyagers. Leaving aside their occurrence in Ohio, there is evidence that they were perfected at a very early period in the history of aboriginal culture in North America. An excavation made in New Jersey, brought to light a number of bannerstones in situ associated with argillite implements and other conditions that proved for them a relatively remote antiquity.*2

According to this evidence at least two forms of bannerstone were produced in New Jersey, not 900 years ago, but several thousand years ago. If, therefore, the bannerstone of America was derived from the double axe of Europe, it was introduced at a very much earlier period than the period to which the earliest historic communications belong. What evidence is there that it was so derived?

The suggestion of Dr. Holmes rests on the undoubted fact that a large class of objects are found in America which, while presenting a wide divergence in form show a general resemblance to the European double axe and sometimes presents such a close approximation that it becomes identical and cannot be distinguished. The suggestion rests also upon the equally undoubted fact that the two classes of objects had a ceremonial use and a symbolic significance. In either case the meaning or set of ideas associated with the use of this symbolism remains unknown.

These circumstances though very interesting and instructive would need the support of substantial corroborative evidence in order to establish anything resembling a positive argument.

There has not yet appeared any such corroborative evidence. If any of the varying forms of bannerstone was derived from a European model it is not likely that the connection can ever be established. An identity even of such a highly specialized form coupled with entire conformity of function is not in itself trustworthy evidence of borrowing.

What evidence is there, on the other hand, for an independent native derivation for the class of objects known as bannerstones?

It has been shown that certain types of bannerstones were in use in America in very ancient times. It can also be shown that an object similar in form was in use within recent historic times and an object similar in form is in actual use down to the present time at one point on the continent. In both these instances the use of the object is purely ceremonial and symbolic. In each instance it is associated with rites which are evidently very ancient and the object itself in both instances is evidently one whose form and symbolic use have been handed down for many generations.

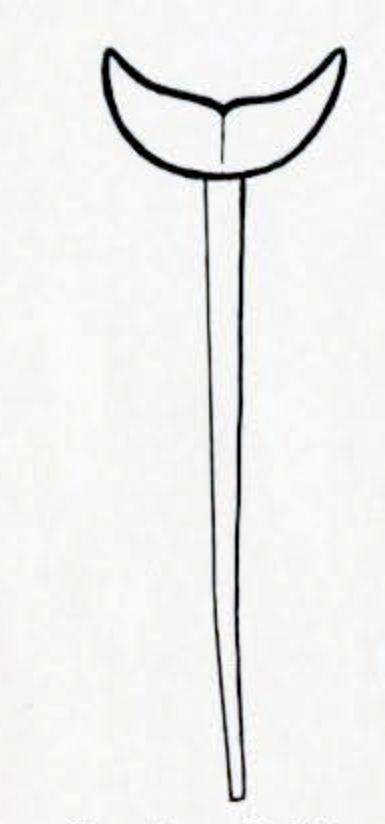

In that very valuable and excellent work by James P. Howley entitled “The Beothuck or Red Indians” may be seen opposite page 249 a reproduction of a drawing made by a woman of the Beothuk Indians and obtained from her in 1829. The Beothuks were the aboriginal inhabitants of Newfoundland and have been extinct for some time. In the drawing to which I refer is seen a series of six staves each surmounted by a symbolic device. One of these, we are told, represents the whale’s tail. With reference to this object Howkey has the following memorandum, referring to the notes of Carmack who first obtained the drawing from the Indian woman. “A note informs us that a whale was considered a great prize, this animal affording them a more abundant supply of food than anything else, hence the Indians worshipped this image of the whale’s tail. (The italics are mine.) Another reference to this occurs among some stray notes of Carmack’s as follows: ‘The Bottle Nose Whale which they represented by its tail, frequents the Northern Bays… and the Red Indians consider it the greatest good luck to kill one…'”

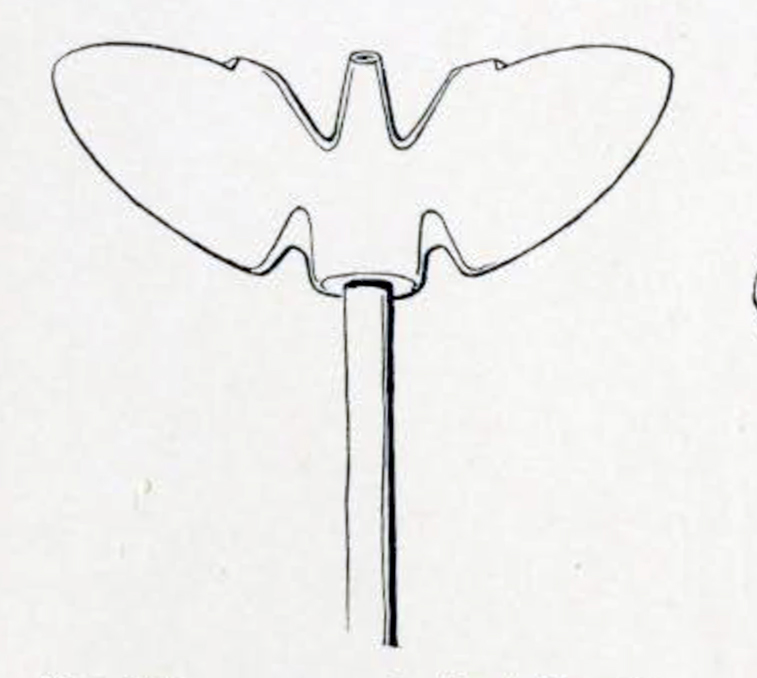

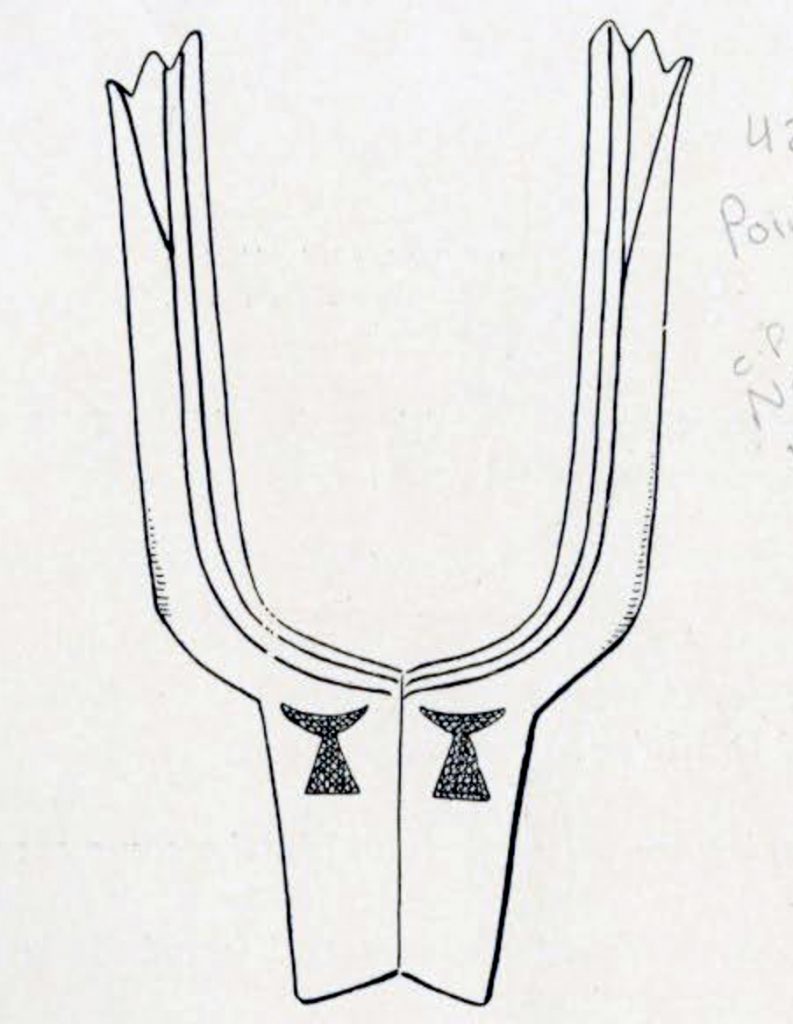

This use of the whale’s tail by the Red Indians of Newfoundland in the early nineteenth century has its counterpart among the Eskimo of Alaska abut Bering Strait and the shores of Bering Sea, and have an elaborate ceremony connected with the whale hunt. In this ceremony they use an object which they declare represents the whale’s tail and which plays a very important role in the ceremony. This symbolic device is made of ivory, either fossil or walrus ivory, and is often tastefully decorated. It has two wings and a pointed projection between the wings at the top. At the lower edge in the center it is partly perforated by a socket for the insertion of the staff on which it is carried. i am unable to explain projecting point at the top which always has deep incision at the end, but it certainly has something to do with the symbolism of the object.

When I was in Alaska in 1905 I was able to obtain several examples of this object which are now in the Museum. I had no opportunity of seeing the ceremony, but from Mrs. Bernardi of Nome who had witnessed many Eskimo ceremonies I learned some of the facts about the ceremony connected with the whale hunt.

At that time and later I noticed that the whale’s tail is a favorite device among the Alaskan Eskimo for carving on ivory or wooden implements and for tattooing on their persons and for charms. This use of the symbol which often at first sight appears to be for decoration has also a deeper religious significance.

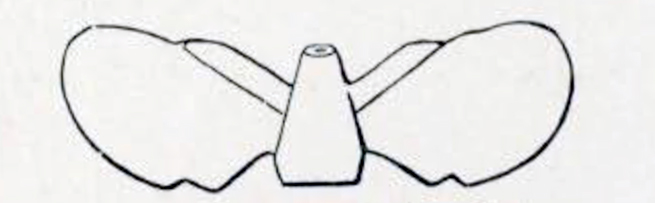

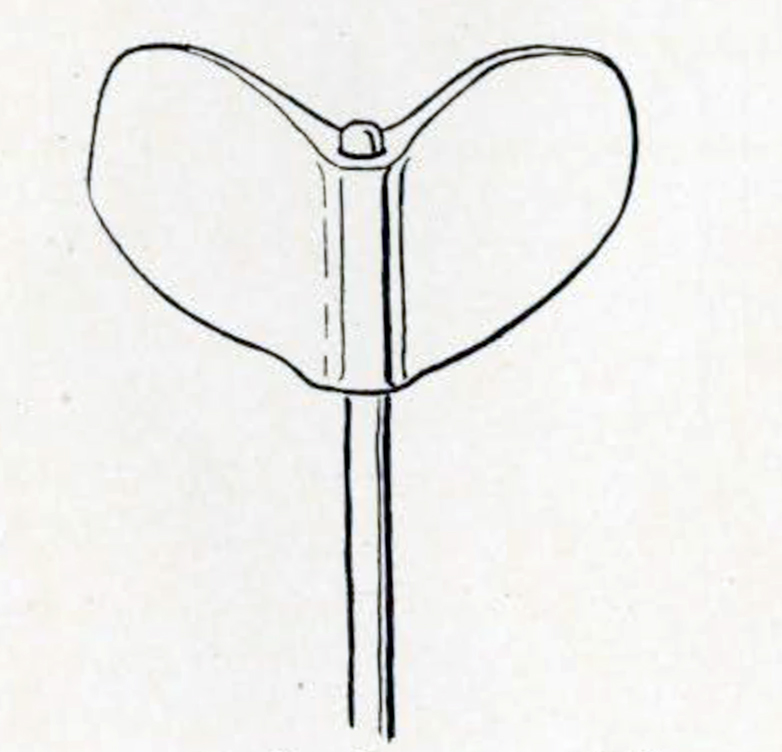

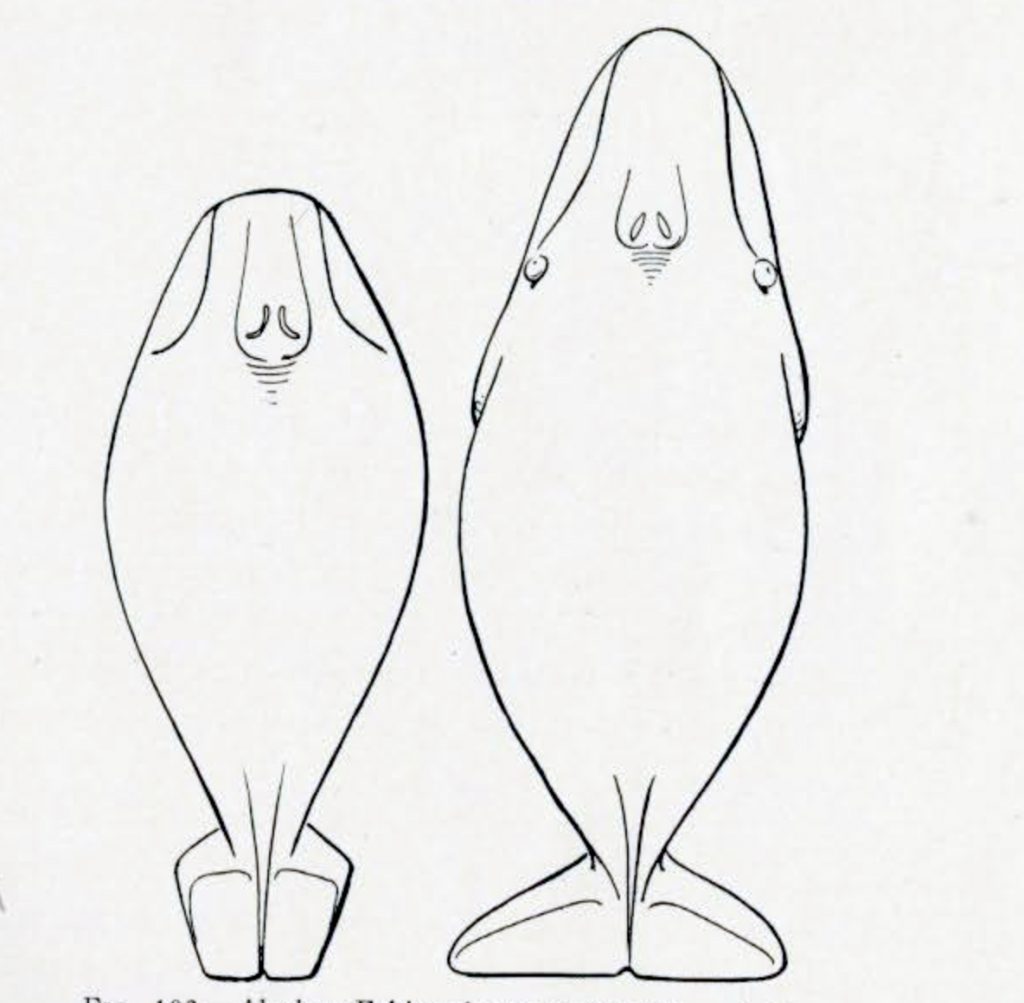

Many emblems are used in the whale ceremony; that which represents the animal’s tail takes two formsedit1. They conform to the tails of whales in wood and in ivory which are used as boxes, playthings, or ornaments among the Eskimo. These two forms correspond closely to two characteristic forms of bannerstones.edit2

The preponderance of the whale and especially of the whale’s tail in the decorative art and symbolism of the Alaskan Eskimo makes it appear as the most important symbolic device known to them. The set of ideas with which this symbol is associated is probably one of the most deeply rooted and powerful of their religious beliefs. The rites of this cult have been practiced for a long time.

The whale’s tail as a religious symbol is therefore found at the two remotest extremities of the North American continent, East and West; in Newfoundland on the one extremity and at the vicinity of Bering Strait at the other extremity. Between the two and covering a wide area are found the bannerstones. This area extends from Ontario to Florida and from Maine to Ohio. None have been found outside this area, and their occurrence grows more rare towards its western and southern margins. If such an object was in use at one time in the western part of the United States its evidence has been overlooked or lost.

A ceremonial object symbolizing the whale and associated with a cult of that animal could come into existence only among a people living near the sea. It would naturally not penetrate to the far interior of a large continental area where the animal could not be known and where its symbolism would not be understood. The bannerstone has its greatest development on the eastern seaboard of the United States and it gradually disappears as one recedes from the coast westward. Its distribution is therefore in keeping with the idea of origin among a coast people. The reappearance of a surviving symbol of similar form at the other extremity of the continent, taken in connection with the historic evidence furnished by Newfoundland, indicates a wide knowledge and use of the same symbolism among the people of the continent dwelling on the coasts of the seas frequented by certain species of whale which are known to have been hunted and used as food from Newfoundland and Labrador to Alaska.

Summing up the whole subject, it will be best to distinguish between different types of bannerstones.

- The one with upward turning wings, monoplane type edit3 characteristic of the eastern area, especially the littoral of New Jersey and Pennsylvania. This form is found also extending westward and southward.

- A tapering form edit4 found in the same area as No. 1 and in close association with it and found also extending westward and southward.

- The double axe form edit5 characteristic of Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin. This form extends down into Georgia, Florida, and Louisiana. In the southern region all forms are rare.

- The butterfly form edit6 found in Ontario, Ohio and the western and southern fringe generally of the bannerstone area.

- The yoke form edit7 characteristic of the Ohio region.

Besides these five forms there are seen in most collections a variety of shapes that are classed as bannerstones. These variants and erratic forms increase as one goes westward and southward and are found chiefly in the western fringe of the bannerstone area.

The meaning of this distribution of forms is either that the different types are unrelated objects derived independently from different origins and representing different ideas or else they represent the variable forms which the same symbol took, on its migration westward from the east Atlantic seaboard. The evidence at hand seems to point to the latter view. That is to say, a symbol which retained its proper form and significance in the place of its origin where its meaning was plain, was naturally subject to many local influences as it passed into regions where it was not well understood, and being subject to varying interpretations, took on many different forms.

Although one form of object usually classed with the banner-stone and closely resembling the double axe of Europe may possibly have been introduced into America from Europe at an early period as suggested by Doctor Holmes, there is strong evidence in favor of a native origin for the bannerstone that is characteristic of New England and the North Atlantic States, and also of a second form which is sometimes found associated with this most characteristic one. These two forms closely resemble two forms of symbol that are still used among the Eskimo of Alaska for ceremonial purposes. The first, the most prominent and characteristic of these two forms, shows a close correspondence to a form of symbol used as late as the nineteenth century by the Beothuk or Red Indians of Newfoundland.

That the possibility of a foreign origin for various elements of Indian culture is a reasonable assumption cannot be denied, but it would seem that whatever aspect of this culture we choose to study, we are likely to be led in our inquiries to purely American sources. For the bannerstone as for all native ideas, a native origin seems to be the most plausible, and it is by pursuing our researches on the American continent itself that we are most likely to find the explanation of ancient American symbols.

G. B. G.

*1Nilsson’s Scandinavia, pp. 71-72 (The Primitive Inhabitants of Scandinavia, by Sven Nilsson).

*2See University Museum Anthropological Publications, Vol. VI, No. 3.

edit1 Missing text that includes 2 images in the sentence, look at pdf version on page 63

edit2 Missing text that includes 2 images in the sentence, look at pdf version on page 63

edit3 Missing image that is within the sentence, look at pdf version on page 66 bullet 1

edit4 Missing image that is within the sentence, look at pdf version on page 66 bullet 2

edit5 Missing image that is within the sentence, look at pdf version on page 66 bullet 3

edit6 Missing image that is within the sentence, look at pdf version on page 66 bullet 4

edit7 Missing image that is within the sentence, look at pdf version on page 66 bullet 5

Museum Object Number: NA3649

Museum Object Number: NA1069

Image Number: 12560

Museum Object Number: NA4245

Image Number: 12560

Image Number: 12097

Museum Object Number: 42100

Image Number: 12561