THERE are now shown in the Middle American Hall four monumental stelae from Pied.ras Negras, one of the results of the Eldridge R. Johnson Expeditions to this ruined city of the Maya ‘Old Empire’ in Peten, Guatemala. Three of these, Stelae 14, 40 and 12, arc exhibited together on a dais at the eastern end of the hall where, their light limestone forms contrasting strongly with the black wall background, they make a striking appearance as one enters the hall. Stela 13, of smaller size, stands to one side, off the dais. Four other stelae were sent to the National Museum in Guatemala City in accord with the contract with the Guatemalan Government.

Image Number: 19364

These monuments are dated to the exact day in the Maya calendar, and their dates indicate that a stela was erected at the close of each five-year period, apparently to mark the passage of this space of time.

Stela 12, probably the most artistic large Maya monument known, was described in the Bulletin for June, 1933.

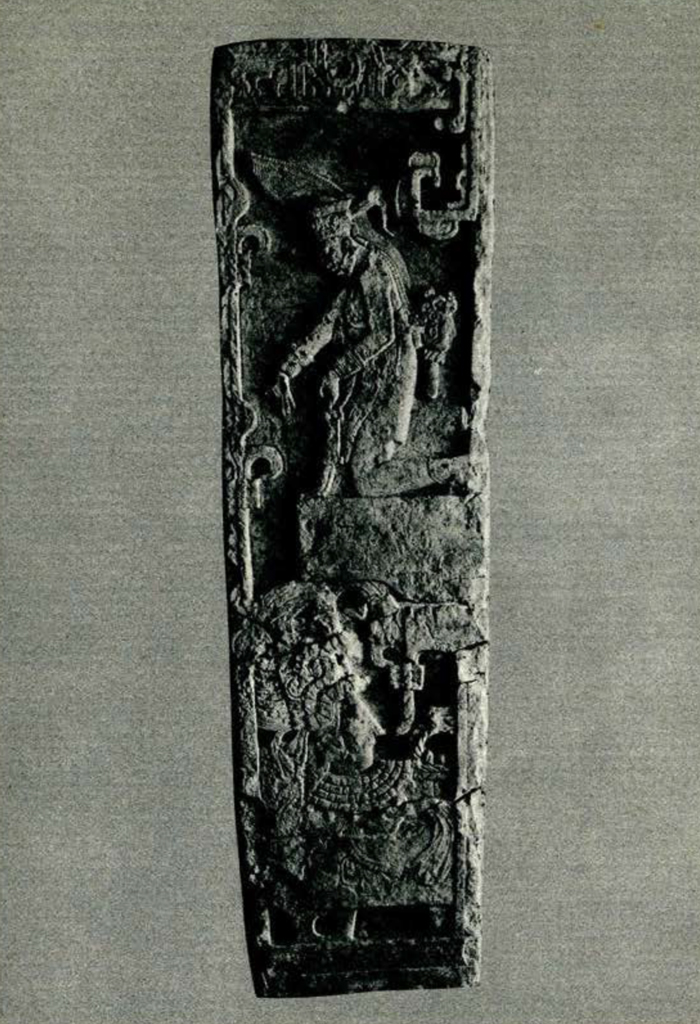

Stela 40, the largest Maya monument in the Museum [Plate IX], stands in the center of the group on the dais. Unlike all the others, it was not found by the discoverer of the city, Teobert Maler, in 1899, hut was unknown until 1921 when it was unearthed by an expedition of the Carnegie Institution consisting of Drs. S. G. Morley and Oliver G. Ricketson, Jr. It was the largest well-preserved monument at the city, and probably as large as any erected there. It was in two pieces when found; if it had been unbroken, the task of transporting it might have been beyond the power of the simple mechanical appliances available to the Museum’s expedition. As it was, the handling of the larger half, which weighs about three tons, taxed the abilities of the staff. The raft on which the great boxes were carried through the last rapid on the river tipped dangerously, but the rivermen were quick and watchful, jumped to the other side of the raft and saved the great stone from loss in the deep water.

The original height of this stela was fifteen feet, eight inches. In order to place it in the Maya Hall, twenty-six inches of the uncarved base that was set in the ground had to be removed, so that at present it appears practically as it did in situ. This lower piece has been preserved and can easily be replaced if and when the monument is moved to another place with more clearance. The original weight of the stela was about five and one-half tons, the present weight as exhibited about five tons.

The task of quarrying, transporting, erecting and carving such a great block of stone were noteworthy feats for primitive people. Of their methods of handling the monuments we know nothing, but as no piece of metal has been found in the ‘Old Maya Empire’ it is universally believed that these people were ignorant of copper and bronze, as well as of iron and steel, and that the sculptures were carved with tools of stone and abrasives such as sand, together with endless time and patience.

The decoration of Stela 40 is much simpler and more reserved than those of the other three stelae. The principal element, near the top, shows a human figure who probably represents the Corn God, though possibly a priest or noble. He wears a great headdress like a bishop’s mitre, and fastened to his back is a human head shown in profile. This is probably a mask of some type, not an actual severed head. With his right hand he drops grains of corn, and in the left he holds a bag which presumably contains more corn. At the base is a large human head shown in profile. The nature of this is uncertain, but it probably represents some deity, and the fact that the corn drops upon this head suggests that it may represent some concept such as the Earth Goddess. The head bears a serpent head-dress. The apparent fleurs-de-lis at the left margin probably represent the leaves of the corn plant.

The date of this monument, 9.15.15.0.0 in the Maya calendar, as given by the glyphs on the side edges, shows that it is the earliest of the four stelae in the Museum. The correlation of the Maya calendar with ours is still a moot question, but the settlement of this problem now apparently lies with one or the other of two schools of thought, each of which proposes a day-for-day correlation. According to one, the date is June 5, A. D. 746, according to the other, the year is A. D. 486.

J.A.M.