MAYAN carved and dated monuments, so splendidly represented in our museum by originals from Piedras Negras, are found scattered over a wide region of tropical lowlands. This is the so-called “Old Empire” of the Maya. The most beautiful are at Piedras Negras but the earliest are in the center of the region to the east. Maya high culture with its hieroglyphic writing, astronomy, art and probably its advanced architecture evidently began in this center, called the “Peten”. Through the centuries it must have spread in all directions among the surrounding Maya. We may suppose that as it did so it encountered local traditions differing from those of the central peoples. At Piedras Negras some of the new ideas were probably rejected, others accepted, the new stimulating mixture giving rise to new forms and a new course of development, especially in architecture. Only thus can be explained the striking fundamental similarities and the equally striking stylistic difference between the two regions as we find them.

Latest form, with simple foundation platform [STR. J-29, Phase A (latest)]; Preceding phase, same style, but with one doorway only. The elimination of doorways may be for greater strength and be connected with early difficulties in supporting heavy masonry vaulted roofs. [STR. J-29, Phase B]; Still earlier period, same style but with doorways. The piers between doors are slightly smaller than those of the latest period. [STR. J-29, Phase C]; The earliest form with complex Peten style substructure. The solid mass behind the room probably supported a large ornamental tower, removed in later periods. [STR. J-29, Phase D]

Image Numbers: 19442, 19443, 19444, 19445

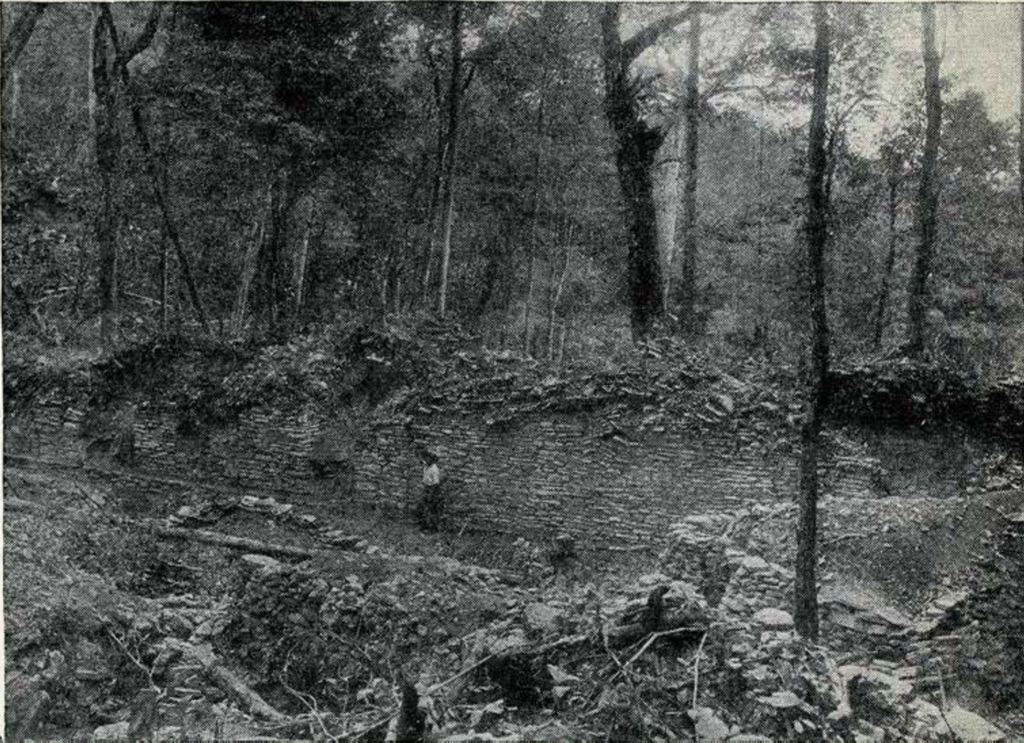

One of the principal achievements of the three month 1936 season was to catch this process at work in several temple designs. The temple numbered J-29 (Plate V, Phase D) was a marriage of Peten architectural style with pre-existing local notions of what a temple room must be. The drawings show the building without its roof as if sliced off horizontally about six feet above the room floor. The enormously thick rear wall was undoubtedly for support of an ornamental tower. This, and the peculiar shape of the building and its substructure, are typical central Peten features, never before encountered in this region. But the three doorway façade is typical of the west, not of the center. The low sill along the rear of the room, the niche with a special kind of stone altar in it, and the ventilator are known in combination only at Piedras Negras itself.

The foreign shape of the building proper survived to the end, but the elaborate substructure on which it stands went out of style and was buried by a simpler one at a later date. (Plate V, Phase C.) After this two of the doorways were eliminated and in the final period again make their appearance in phases B and A, respectively. In all phases after the earliest the elaborate Peten style substructure was buried.

With the discovery of three thrones of a new type notable progress was made in determining the real function of the Maya long buildings (Plate VI). It has been supposed they were residences of the priests. With a total of five thrones now known in as many palaces it is clear that they were in part used for ceremonies of the sort depicted on our beautiful lintel 3. (See Bulletin, Volume 6, No. 4). The new examples were provided with special rooms at one side, with a connecting window rather than a door. One cannot help wondering if these rooms were not for storage of priestly or regal paraphernalia and the painted books or codices of the city.

The museum will shortly receive its first example of middle period sculpture, a beautiful fragment broken up by the Maya and used as mere building stone (Plate VII). In any museum not already rich in Maya sculpture, this piece would be assigned a place of honor. Deep trenching below temples in search of elaborately furnished tombs was fruitless, though important additions to our collections of pottery fragments and figurines and of fine stucco work were made.

Our stay was enlivened by a visit from a Lacandone Indian, one of the remnant of Maya who still live among the ruins built by their ancestors, refusing to take up the white man’s culture. He is shown with Messrs. Colmont and Dechaume, two French explorers who persuaded him to come.

Plate VI shows in course of construction the type of bush house in which everyone now lives. But this is a very special one, built under the direction of the Guatemala inspector, Don Victor M. Pinelo whose home is to the east. It differs from the local variety especially in its rounded corners, and represents architectural influence from the central Peten district again at work at Piedras Negras, after the lapse of hundreds of years.

The staff consisted of Francis M. Cresson, Jr., assistant archaeologist; Miss Tatiana Proskouriakoff, architect; Mrs. Satterthwaite in charge of camp, objects, catalogue and books; and the writer. Two of them are shown on a Sunday outing. Shooting these rapids in this type of dugout canoe fashioned from a single log was undoubtedly a regular incident in ancient Maya trade and communication, as it is today.

L. S., Jr.