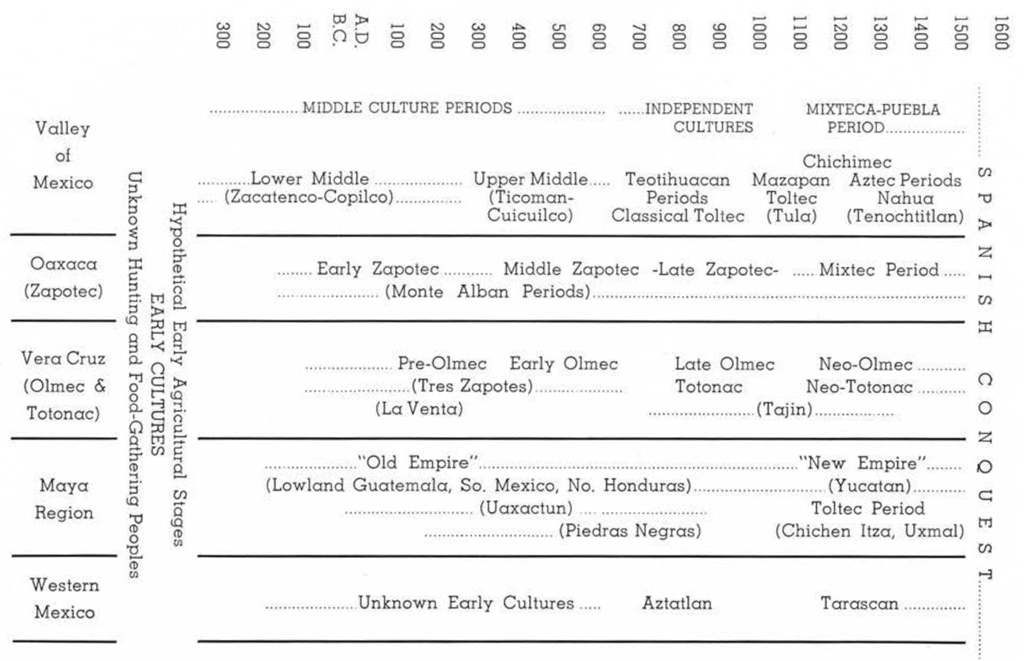

Of the early nomadic hunting peoples of Mexico who must have preceded the sedentary agricultural ones we know nothing. So far no site has been discovered that shows evidence of the early stages of agriculture and of pottery making, which generally accompanied it. The earliest peoples yet known to us were already far along the road to civilization, with permanent villages, well-developed agriculture, and highly perfected and diversified manufactures of pottery, weaving and other techniques and materials. Formerly known as the “Archaic Cultures,” the term “Middle Cultures” is now applied to them, reserving “Early Cultures” for the yet unknown hunting peoples.

The Middle Cultures

Probably about 200 B.C. a group of these farmers moved into the Valley of Mexico. Here by the shores of salt Lake Texcoco (which still exists, though much reduced in size by artificial drainage) they built their villages and tilled their fields further inland. Unknown even to historical tradition, our knowledge of them is based entirely on archaeological excavation, mainly due to the work of Dr. George C. Vaillant, now Director of the University Museum. Their refuse deposits which total more than twenty-five feet in depth, thus indicating a long period of occupation, rest on sterile ground, proving that, at these sites at least, they were the first sedentary inhabitants. They found the region a most hospitable one; the wash from the volcanic hills offered fertile soil, the great springs abundant fresh water, the marshes numerous water birds, and the hills sheltered deer and other game. This Middle Period is divided into two phases, a Lower Middle from about 300 or 200 B.C. to about 400 A.D., and an Upper Middle lasting until about 600 or 700 A.D. At Copilco in the suburbs of Mexico City some graves of the Lower Middle period have been found which were covered by a flow of lava that probably occurred about the latter date. This lower phase apparently did not extend beyond the confines of the Valley of Mexico.

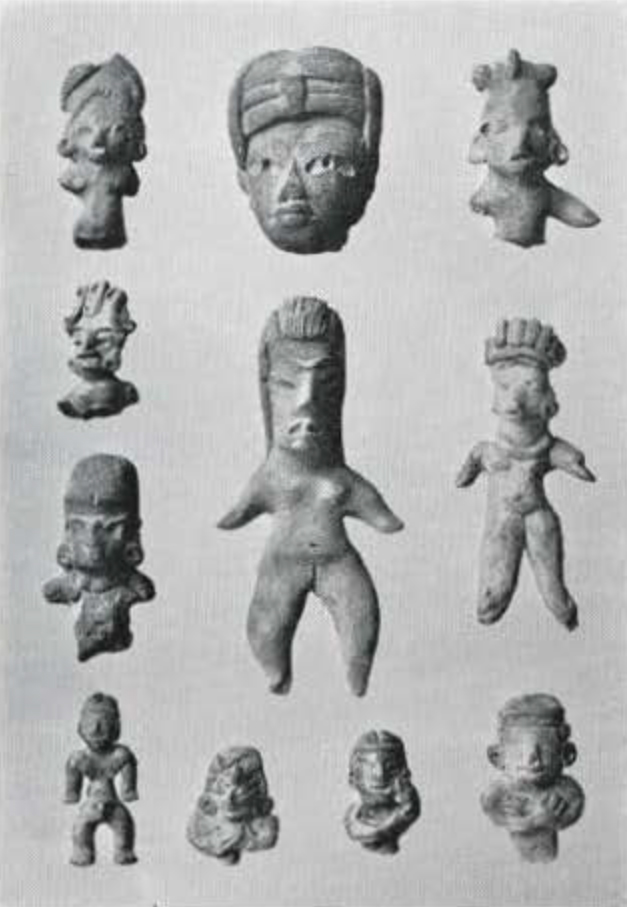

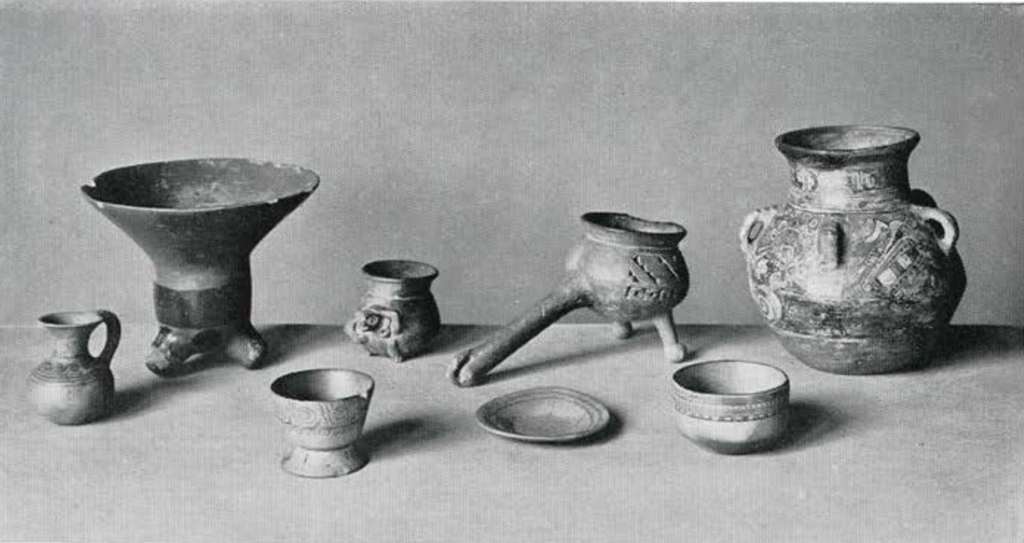

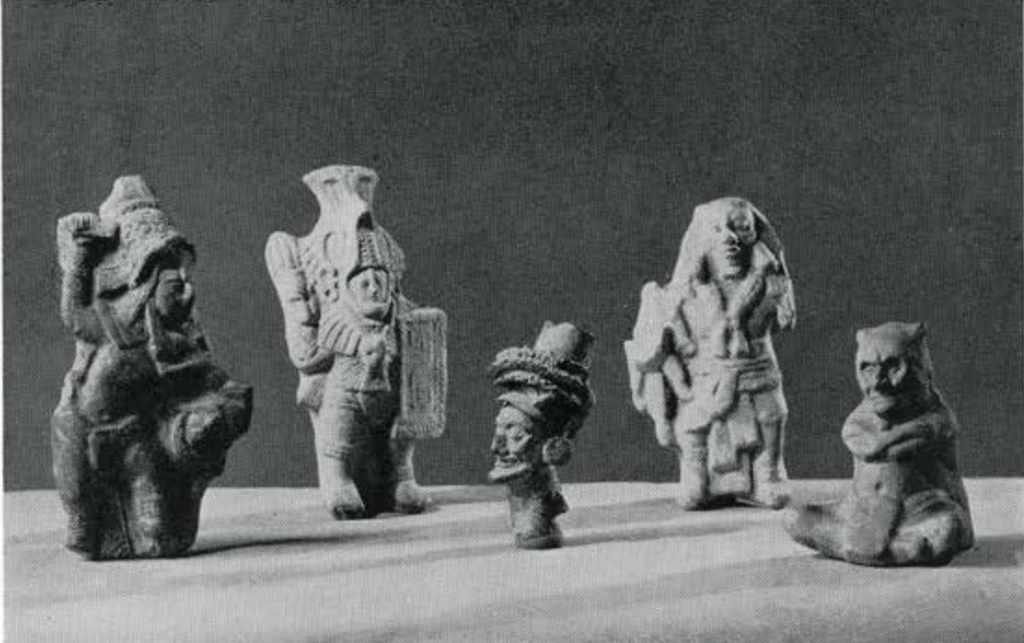

Their economic life probably differed very little, except for the greater supply of wild game, from that of the Mexican peon today. They built their houses of wattle and mud, ground their corn with manos on metates, wove garments of cotton and plant fibres, and made tools of stone, bone, shell and wood. Of the arts in basketry, wood, and such perishable products we know nothing, as none of these have been preserved. A tiny fragment of cloth indicates a weaving industry. The pottery vessels were mainly coarse and utilitarian, but others of better quality, with painted or incised decorations, were also manufactured. Their most characteristic products, however, were the little pottery figurines, generally representing women and probably goddesses, which are found in great quantities, though generally in a broken condition. These were hand modeled with the details and decorations applied; a number of different types, characteristic of minor temporal periods and different sites, have been differentiated. (Figure 2)

Museum Object Number: 11300 / 87-42-957 / 87-42-897 / 31-41-61 / 31-41-60 / 87-42-899

Image Number: 20000

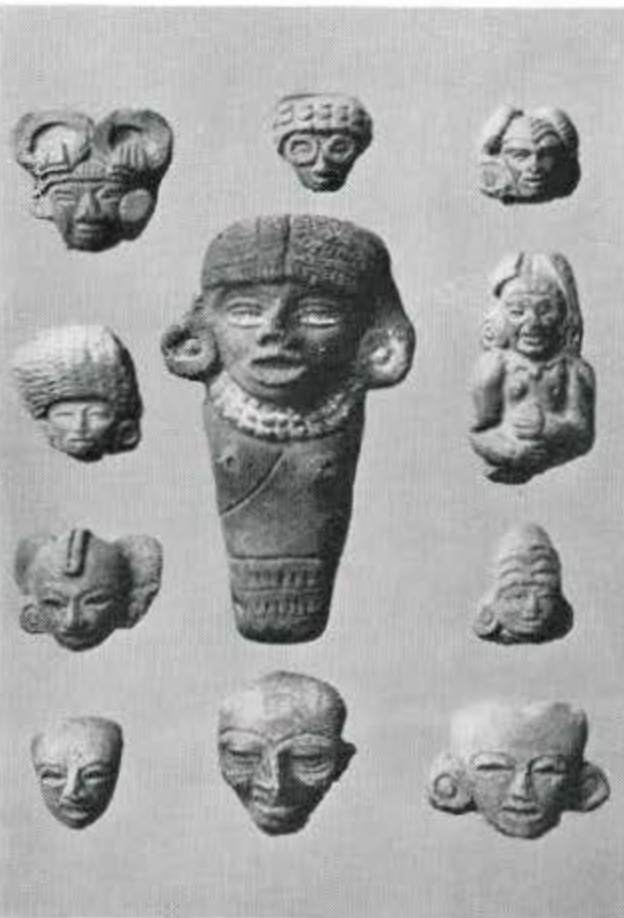

The Lower Middle Culture showed little of the emphasis on the religious aspect that was to characterize the later periods. This first appears in the Upper Middle Culture. It was evidently introduced from outside of the Valley, probably from the nearby region of Puebla, or even possibly from the Olmec area of southern Vera Cruz; some of the figurines show an art style peculiar to the latter region. It does not follow, however, that the actual immigrants were from the Olmec region. This culture extended beyond the limits of the Valley. The economic life continued on the same basis, with a lesser dependence on wild game which by this time was disappearing. The pottery vessels, figurines and other artifacts were more variant and better made and decorated, but basically similar except for the introduction of negative-painted (batik) ware.

Religious architecture now began, with terraced pyramids, ceremonial centers and city planning. The most impressive relic of this period is the great oval mound or pyramid at Cuicuilco, not far south of Mexico City. Built of earth and uncut stone it is some 370 feet in diameter and sixty feet high, and had an open altar on the summit. It was twice enlarged by covering with a new layer and had apparently been abandoned when, about the year 700, it was partly covered by the same lava flow that sealed the earlier graves at Copilco.

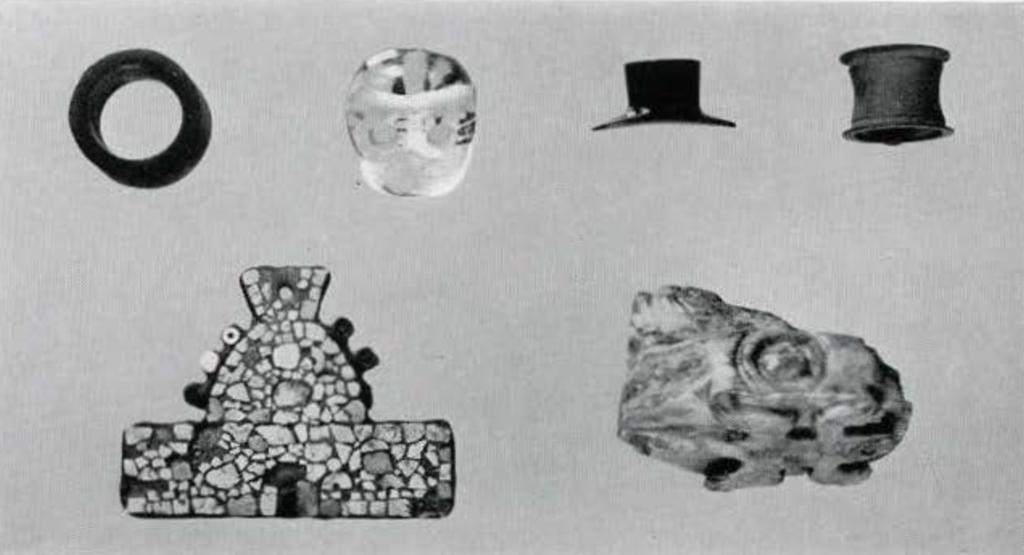

Museum Object Numbers: 87-42-422 / 87-42-419 / NA10799 / 87-42-421 / 97-83-157 / 2019-11-2

Image Number: 20003

The Teotihuacan and Toltec Periods

With the close of the Middle Period we cease relying exclusively on archaeological investigations, and tradition, a few groins of history mingled with the chaff of mythology, comes to our aid. The Toltecs appear on the scene. The quasi-historical legends, written down at the time of the Conquest, tell of a cultured notion that preceded the Aztecs in the Valley of Mexico, and from whom these less civilized invaders borrowed most of their arts. The Toltect capital was called Tula, and the traditions recount the dynasties and history of the Tula Toltecs. Archaeological excavations in the Valley of Mexico have revealed a highly developed culture of long occupation between the archaic Middle Cultures and the Aztec. Since this type is found in greatest purity at the great ceremonial center of Teotihuacan, not far from Mexico City, it was naturally assumed that Teotihuacan was the traditional Tula, and that the objects there found were typical of the Toltecs. To this day all popular archaeological works on Mexico have identified Teotihuacan with the Toltecs. Recent excavations at the town of Tula in the state of Hidalgo, however, have shown almost beyond argument that this is the historical Toltec Tula. The culture there found is that heretofore known as Mazapan, a relatively brief period subsequent to the apogee of Teotihuacan. The builders of Teotihuacan were therefore the predecessors of the classical Toltecs of the annals; there are no certain allusions to them or to the site in the traditions. They may have been pre-dynastic Toltecs but possibly were of other tribal and linguistic affinities.

The culture of Teotihuacan developed from the last phases of the Upper Middle Cultures. The depth of the deposits indicates a rather long period of occupation, generally estimated as between 500 and 1000 A.D., though some authorities start the period at 300 and others end it at 1100. Archaeologists distinguish five developmental stages. The remains of towns of the Teotihuacan period and culture are found throughout the Valley of Mexico and even in a considerable area outside of the Valley, and Teotihuacan influence reached much further afield.

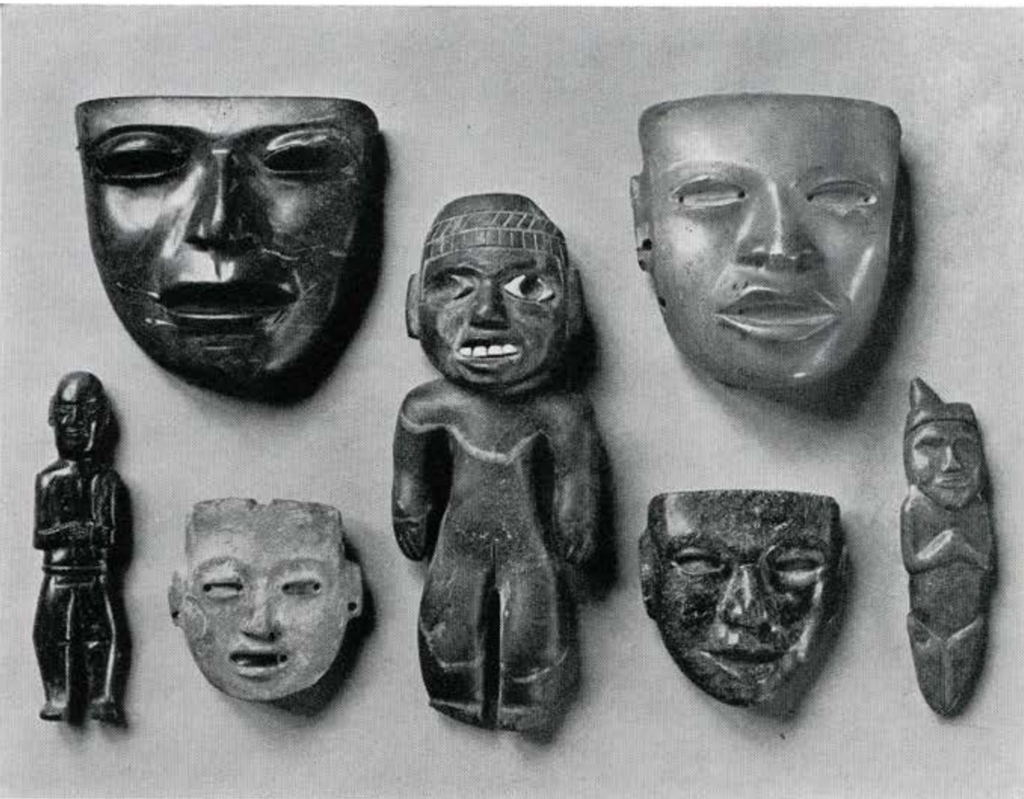

Museum Object Numbers: NA6362 / 87-42-416 / 37-13-196 / 2019-11-3 / 82-42-415

Image Number: 20072

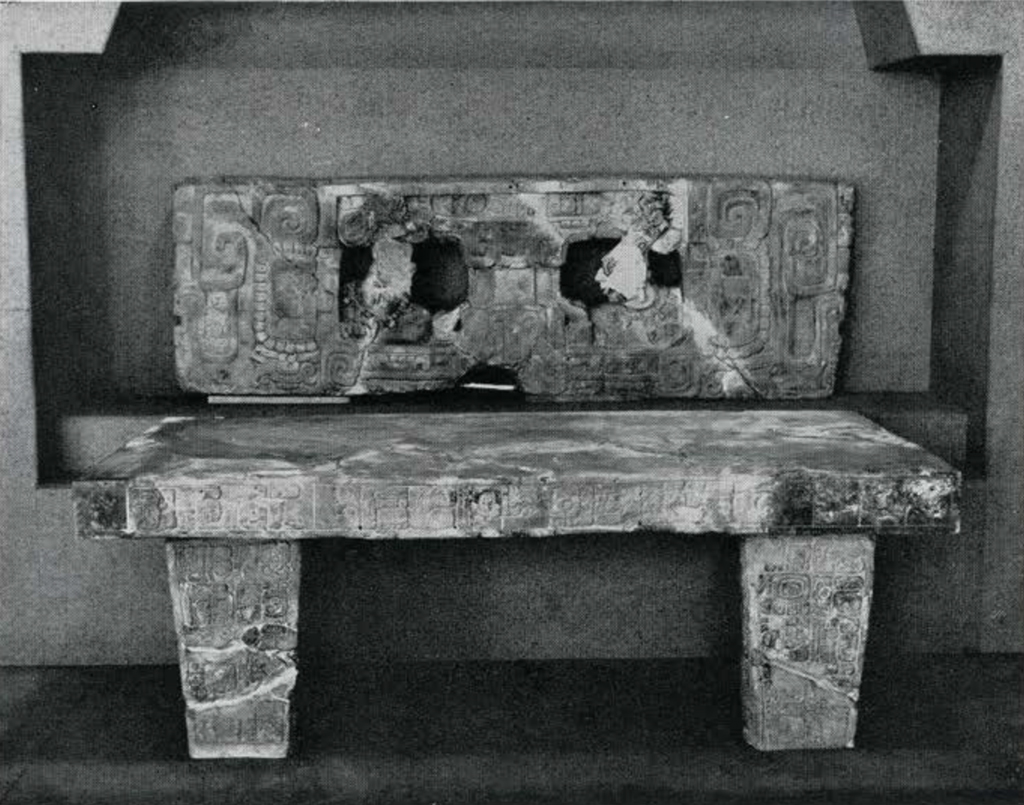

The great ceremonial site of Teotihuacan is one of the largest and most impressive in the world, some six square miles covered with, at present, the ruins of buildings and their pyramidal foundations. The entire area may originally have had a plaster floor. Towering over all is the great Pyramid of the Sun which originally covered a greater area than the largest pyramid in Egypt, over seven hundred feet on a side, but is a third lower, a little over two hundred feet in height. The entire outer facing was removed in an ill-conceived restoration in the first decade of this century. It is built of adobe (sun-dried mud) bricks, has a stairway up the side and had a temple on the small truncated top. The Pyramid of the Moon is smaller. Some of the many buildings have been excavated and have revealed in their several superposed structures painted frescoes and quantities of objects, especially pottery figurines and small censers. Probably the entire site was devoted to ceremonial purposes. (Figure 3)

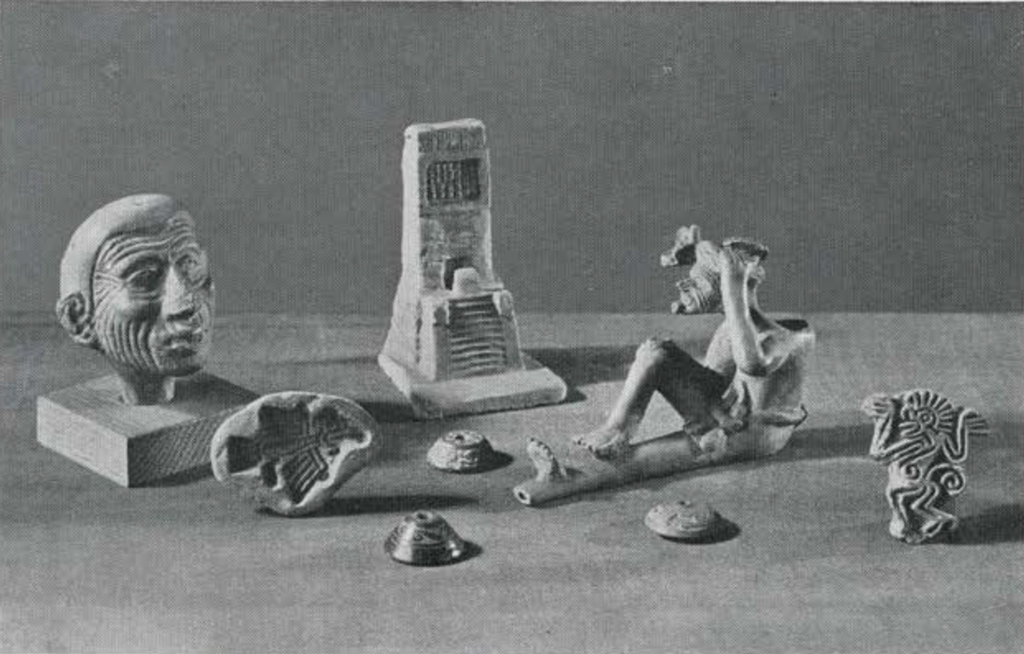

Ancient traditions, as already stated, recount the history and dynasties of the Toltecs of Tula. After many centuries of building and rebuilding, of architectural development and superposition, Teotihuacan was abandoned, probably about the year 1000, and not again used. Toltec culture undoubtedly assimilated all the high elements of the Teotihuacan peoples, and built upon and improved them. The material remains of the Tula Toltecs are those heretofore known as Mazapan, considerably different from and not directly developed from, those of Teotihuacan.

Museum Object Number: 87-42-992 / 29-41-600 / NA6354 / 31-41-58 / 12905 / NA6342 / NA5592

Image Number: 19997

The dynastic Toltecs of Tula, or Toltecs of the annals, may have been the first of a number of invaders into the Valley of Mexico from the north, during the period of several centuries that intervened between the Teotihuacan and the Aztec eras. These immigrant peoples were collectively known as Chichimec, a name that implies barbarians of lower cultural status; the Aztecs themselves were the last wave of this invasion. The Toltecs apparently spoke a language closely akin to that of the Aztecs, but peoples of entirely different linguistic groups were included in the designation Chichimec and were associated with the migrations of the Chichimec period.

The Tula Toltec “Empire” apparently lasted for about one hundred and fifty years, probably somewhere between the years 1000 and 1250. Then it “fell,” overrun by another Chichimec wave, possibly that of the Aztecs themselves. The Chichimec period naturally overlaps that of the Toltecs on one hand and that of the Aztecs on the other, and is generally placed al about 1100 lo 1300 A.D. Toltec blood and culture however remained virile; certain centers such as Texcoco and Azcapotzalco, the latter now a suburb of Mexico City, remained wholly Toltec far into Aztec times and preserved Toltec traditions. The Aztecs looked up to the Toltecs as their masters and teachers in all the arts, made few improvements in their techniques, and boasted of Toltec blood in their lineages.

Museum Object Number: 31-41-40 / NA9268 / 4208 / 15083 / NA2151 / 34-34-1 / 31-41-52

Image Number: 19968

The Mixteca-Puebla Period

Probably some time in the twelfth century began a period of renaissance, of even greater emphasis on ceremonial and ritualistic symbolism, which was to produce a complex of traits that molded into a like form all the higher civilizations of Mexico. The protagonists of this awakening seem to have been peoples of two separate linguistic families, the Mixtecs of northern Oaxaca and the Nahuas of the region of Puebla. from these centers spread the worship of a relatively uniform pantheon of deities, similar ceremonial practices and religious symbolism, a development of a rather un-American emphasis on lineage and dynasty, the evolution of a complex and accurate calendar, a system of pictorial writing or representation, and even similar styles and techniques in art and architecture. This era or cultural phase is known as the Mixteca-Puebla period. Its most prominent exponents were the Aztecs or Tenochca of Tenochtitlan, the ancient City of Mexico.

The Aztecs

The later history of the Aztecs is well known through their traditions, but their beginnings are shrouded in myth. They probably came, as their legends state, from the north, though probably only from the north central part of Mexico. Their language, still spoken by hundreds of thousands today, is distantly related to that of many other northern Mexican tribes, such as the Yaqui, and even to the Pima and Utes of our western states. As has been said, they were only one of a number of tribes, collectively known as Chichimec, who arrived in the Valley of Mexico somewhere about the year 1200. Their difficulties in the next century or more, as vassals or mercenaries of earlier Toltec or Chichimec towns, need not be recounted here. About the year 1325 they established their town, Tenochtitlan, on an island in Lake Texcoco. This is today the center of great and beautiful Mexico City, the lake level having been greatly reduced by drainage.

Museum Object Number: NA5977 / 87-42-89 / NA5994 / 87-42-91 / NA5194B / 29-150-20

Image Number: 20095

Warlike in national spirit, the Aztecs or Tenochca soon became the dominant power in the Valley of Mexico. Forming an alliance with two other towns, Texcoco and Tlacopan, they soon subjugated all the other small groups in the locality. Later, Aztec armies conducted campaigns as far afield as to attack the Huaxtecs, the Zapotecs, the Tarascans, and even the peoples of Guatemala. By 1450 they had vanquished most of Central Mexico. None of these nations was actually conquered, but there and in the intervening regions the Aztecs had nominal control and received annual tribute. Their constant wars and forays seem to have been not so much for national aggrandizement, booty and tribute, as for securing captives for religious sacrifice.

At the time of the conquest by Cortes in 1519 Tenochtitlan or Mexico City was a magnificent city that excited the admiration and cupidity of the conquerors. Its population is estimated at three hundred thousand. The ceremonial center, containing the palaces of the great chiefs, the many temples on their pyramids, ball-courts and other public buildings, was built of stone masonry, while houses of wealthy families of lesser importance were of adobe bricks. Three great causeways crossed the shallow lake to the mainland, and an aqueduct brought fresh water from springs at Chapultepec. Canals largely took the place of streets.

Museum Object Numbers: NA5996 / NA5909 / NA5908 / NA5907 / NA5906 / NA5877

Image Number: 20095

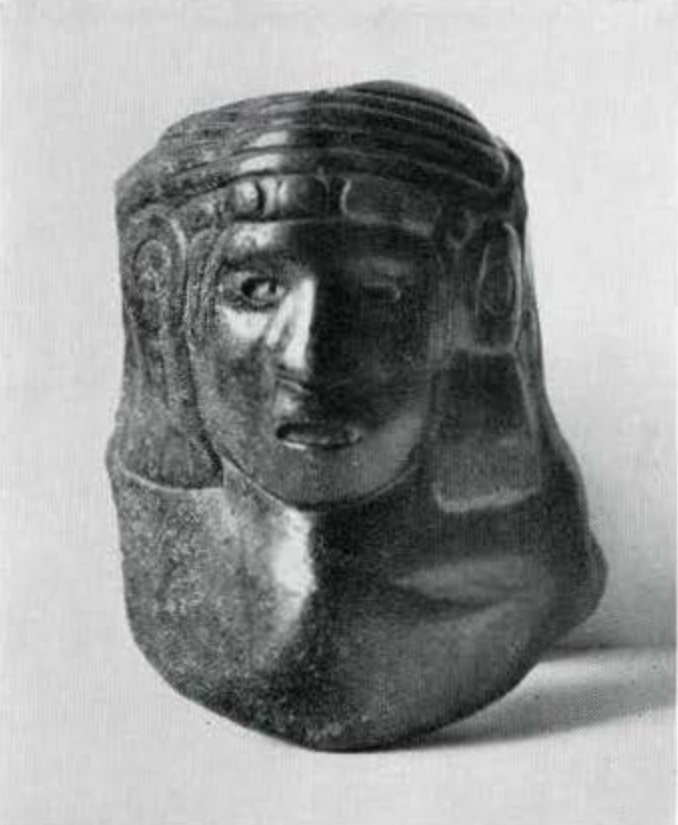

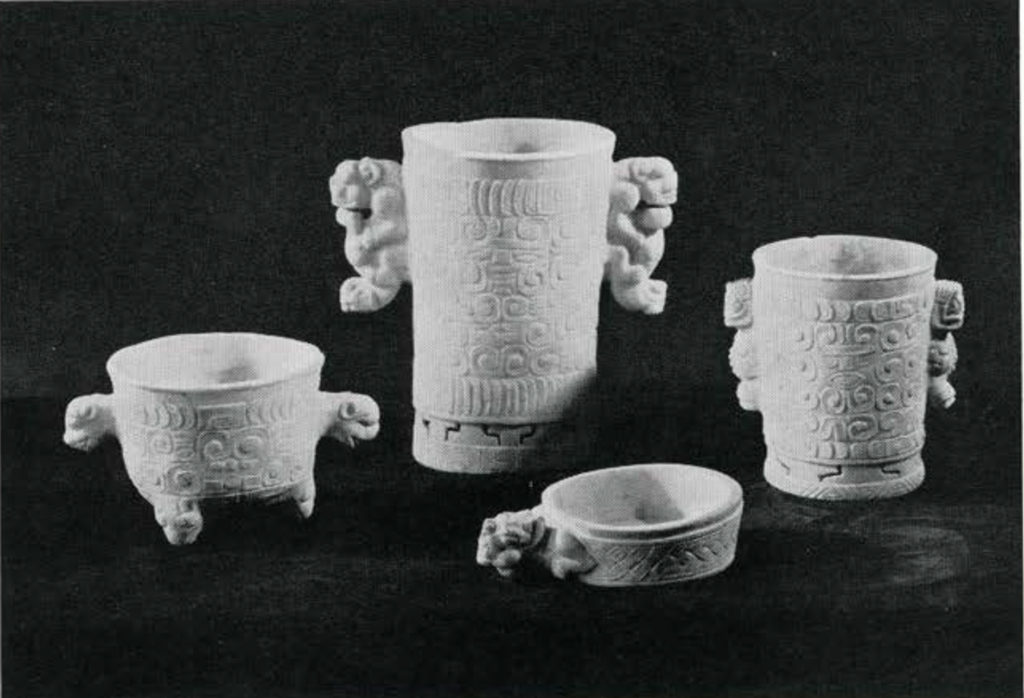

The economic life of the average Aztec differed in little from that of all Mexican Indians of that day and of today. His staple foods were corn, beans and chile, his home a thatch-roofed hut. His scant clothing was of woven cotton or maguey fiber. Every man, in addition to being a farmer, had some trade, some handicraft, and generally each village specialized in the manufacture of some product. Pottery vessels and figurines, textiles, work in stone, metal, wood, and mosaic in feather and turquoise were among the most important industries. Iron tools were unknown, and copper and bronze ones rare. Gold and silver were employed for artistic and religious purposes, but jade was more highly prized than either. All these products excited the admiration of the Spaniards, who mistook the fine cotton textiles for silk and said that the work in gold was superior to that of the best artificers in Spain. (Figures 4-15)

These products and manufactures were bartered in markets, as there was almost no currency except cacao (cocoa) beans, though hollow quills of gold dust and thin blades of copper had a limited use. Trading merchants made long journeys to distant parts and formed a special guild, protected by military power, since they also served the nation as spies.

Museum Object Numbers: 2019-11-7.1 / 2019-11-7.2

Image Number: 19962

Museum Object Number: NA9269

Image Number: 20024

As everywhere in America, the idea of private ownership of land was inconceivable; fields were allotted to families for cultivation. Although the Spaniards, steeped in European tradition, saw everywhere emperors, kings, princes and nobles, the social organization was essentially a democracy, the population divided into small and major groups, each with its council which appointed its representative to the larger group. The Aztec “rulers,” however, were generally selected from one family or lineage; the former government by the council of the clan had been superseded by that of the hereditary chief. There was no aristocratic class, but rank and honor could be obtained by those who had achieved marked success in war and in certain other activities. Beneath these, and beneath the common man, was a small class of military captives and slaves, generally aliens, but also including some who had been condemned to slavery for crimes, or had sold themselves into this condition for economic security.

Religion was intimately bound up with every phase of life and every activity, and the government was practically a theocracy. Temples, major and minor, were as omnipresent as churches in Mexico today; in fact, most churches were built on the sites of pagan temples. The pantheon was large, with many gods and goddesses, each with his special attributes, interests, regalia and ceremonies. Each day was dedicated to some deity, and some ceremonial ritual appropriate to his nature was then celebrated. The religion was thus closely bound up with the calendar.

Image Number: 20105

Almost every one of these ceremonies climaxed in human sacrifice, the most characteristic feature of Aztec religion. The gods, on whose good will the welfare of the nation depended, required sacrifice and nourishment, and human life, hearts and blood were naturally the most dear and desirable. Though in a few cases, to suit the nature of the deity, the procedure was altered, the standard practice was for the priest to open the breast of the victim, not invariably a man, tear out the heart, and offer it to the image of the deity. The word “victim” is not quite appropriate, for sacrifice was an honorable death, martyrdom for the welfare of the nation, and insured one a paradisal eternity. There are recorded instances of prominent men who demanded sacrifice as their fate, but nevertheless alien captives composed the great majority of sacrifices. The cult of human sacrifice was probably at its peak at the time of the Conquest, and the numbers thus immolated were almost incredible; at the time of the dedication of the great twin temples to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc twenty thousand are said to have been sacrificed, though allowance should be made for both Aztec and Spanish exaggeration. Huitzilopochtli, “Hummingbird Wizard,” was the God of War, the most prominent Aztec deity; Tlaloc was the Rain God. Among the most important of the other gods and goddesses were Tezcatlipoca, “Smoking Mirror,” the chief god of the pantheon; Quetzalcoatl, “Feathered Serpent,” God of Learning, Priesthood, and the Wind; Xipe, “The Flayed One,” God of Seedtime; Huehueteotl, the “Old Old God,” God of Fire; Coatlicue, “Serpent Skirt,” the Earth Goddess; and Chalchihuitlicue, “She of the Jeweled Robe,” the Water Goddess. (Figures 4, 12)

Image Number: 20097

The priesthood was large. In addition to conducting ceremonies the priests practised divination, determined lucky and unlucky days, made astronomical observations, kept track of the very accurate and complicated calendar, and painted and interpreted the native books or codices. The calendar was similar to that of the Maya, but possibly less developed; their period records did not extend beyond the sacred cycle of fifty-two years. It was feared that the earth would come to an end at the close of any one of these cycles, and the most solemn ceremony of the nation, that of the “New Fire,” was held at the end of every such cycle. At this time all household equipment and temple furnishings were destroyed and replaced by newly made ones, and the religious and civic edifices were refurbished and enlarged. The great “dumps” of refuse that resulted from this wholesale destruction, and the additions to the temples have furnished archaeologists with a fifty-two-year timetable for their estimates of temporal periods.

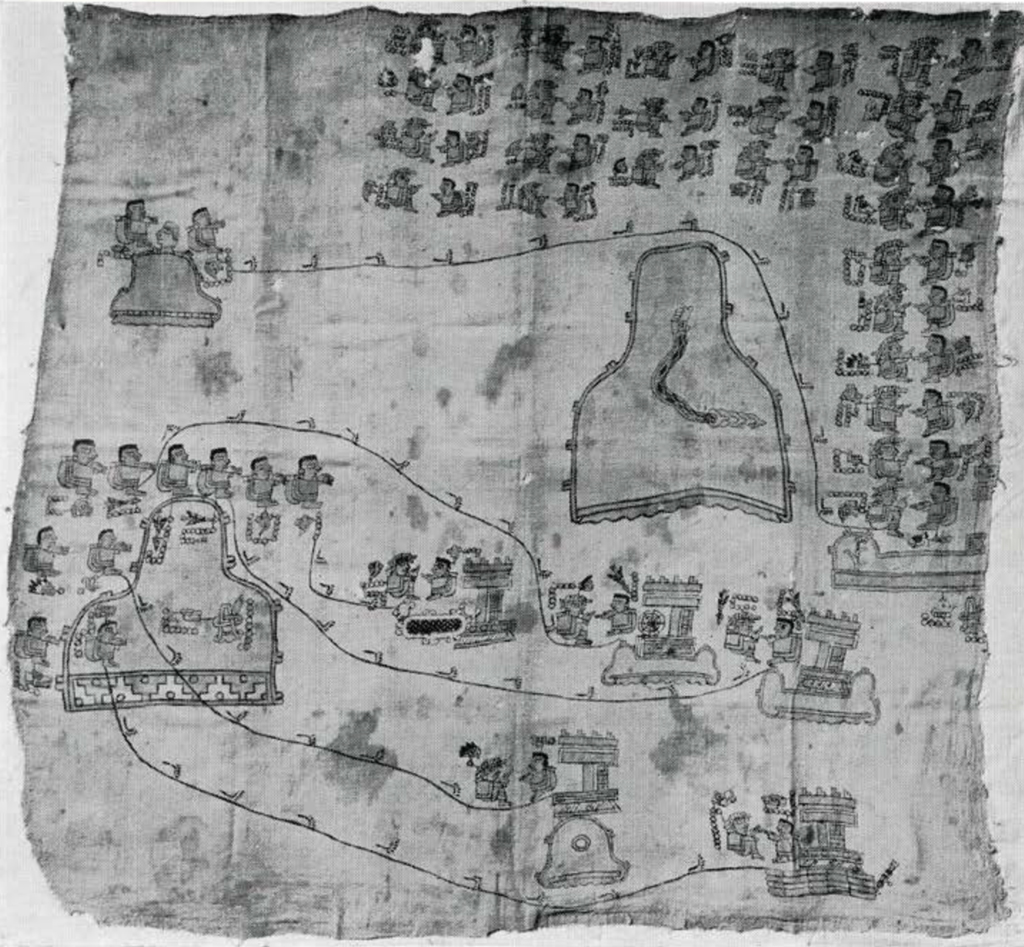

The books or codices, made of paper of bast of the wild fig tree and folded like screens, were painted with figures in many colors. They consisted of conventionalized pictures, together with certain generally understood symbols, and recorded historical tradition, genealogies, the sequence of ceremonies, lists of tribute, and similar data. While far from being alphabetic, the system of writing had progressed beyond that of pure pictography to that of ideography, iconography, or writing by rebuses; this was mainly used, however, in the recording of proper names of places and persons. (Figure 15)

Museum Object Number: 42-7-1

Image Number: 19820

Image Number: 19382

Museum Object Numbers: NA11571 / NA10977 / NA11027 / NA10976

Image Number: 19538

Museum Object Numbers: NA5528 / NA5526 / NA5527 / NA5529

Image Numbers: 19505, 19509