Museum Object Numbers: 29-41-706 / 29-41-726 / 29-41-708 / 29-41-729

Image Numbers: 19916, 19917, 19924, 19925

WE have described the Aztecs and their culture in some detail because they were in their zenith at the time the Spaniards overwhelmed Mexico, and had subdued most of the other native cultures and peoples, but this does not imply that they were superior to the latter except by force of arms. A half dozen other nations in other parts of Mexico, speaking other languages, were their essential equals in culture, though differing in details, and had been their cultural superiors in earlier days. Each had its own long history and its peculiarities of manufactures, architecture, and religious ceremonialism. We can touch but briefly upon these and their outstanding features. Almost any one might have been chosen for description as a typical Mexican people instead of the Aztecs, and most of the data on the latter would apply equally well to them.

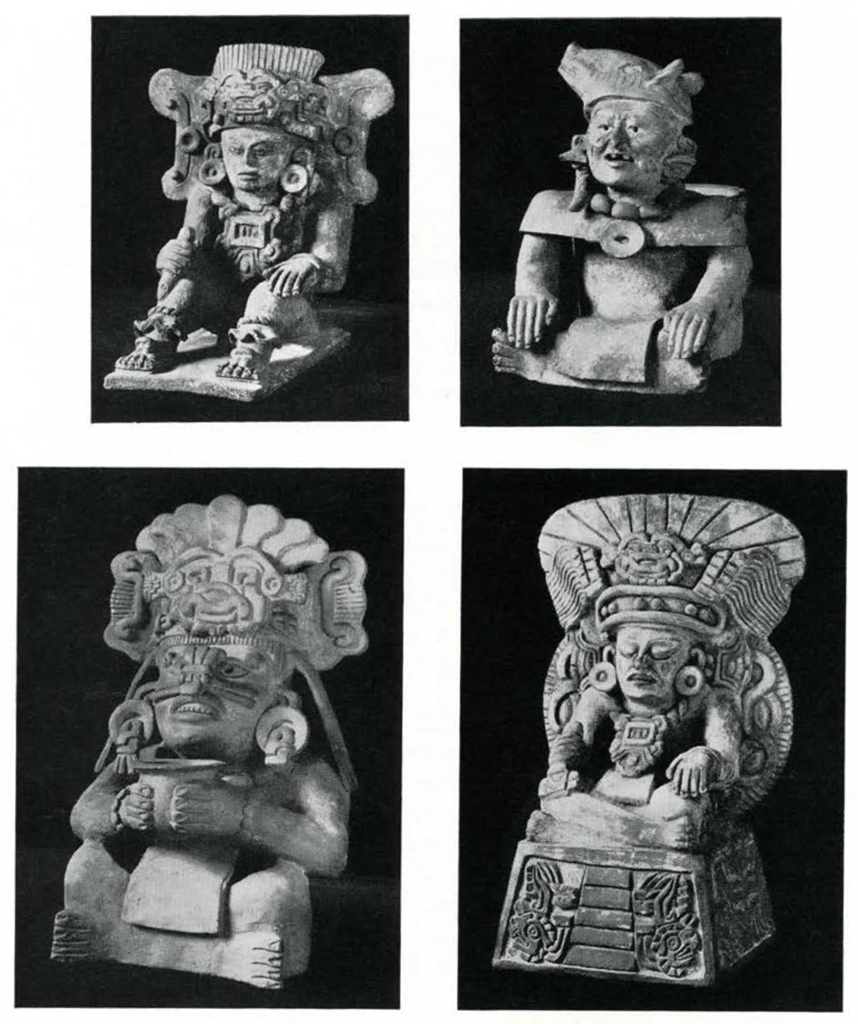

Museum Object Number: 29-41-739

The Zapotecs occupied large parts of the state of Oaxaca, their great ceremonial center being the ruin of Monte Alban near the City of Oaxaca. Here is a site second only to Teotihuacan in grandeur and complexity. The excavations of Alfonso Caso for the Mexican Government during the last decade have shown that the beginnings at Monte Alban were coeval with the later stages of the Early Middle Cultures in the Valley of Mexico. In certain respects, such as calendar and hieroglyphs, the Zapotec formed a link between Maya and Aztec. In this they somewhat resembled the Olmec, with whom they had close relations in early days. Monte Alban was occupied until the time of the Spanish Conquest. In a late tomb was recently unearthed the most magnificent array of jewelry ever found in America. Archaeologists distinguish five developmental periods, the last one of which was introduced by the Mixtec, who brought in the same generalized Mixteca-Puebla culture that produced the Aztec florescence. The Mixtecs probably also built the beautiful masonry buildings at Mitla with their mosaic decoration of thousands of small cut stones, probably the best preserved ruin in Mexico. Most characteristic of Zapotec archaeology are the ornate pottery censer urns that were placed over the doorways to tombs. (Figures 10, 14, 15; 25, 26)

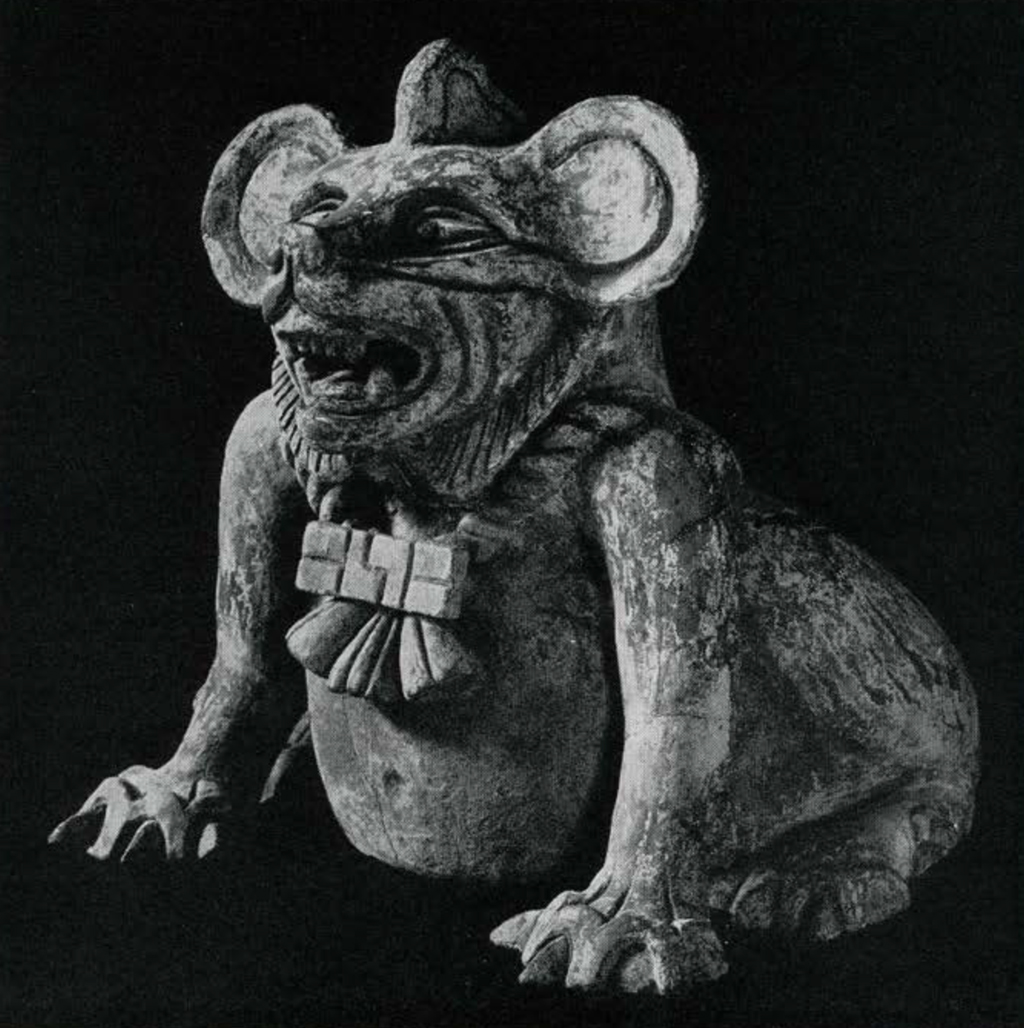

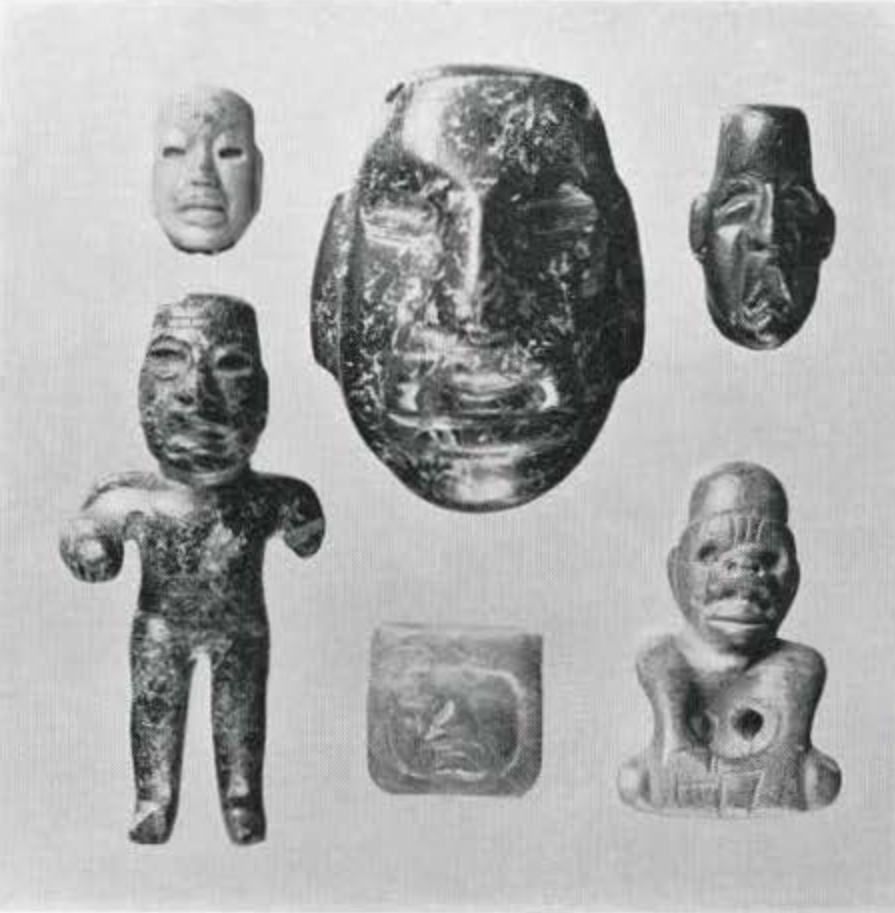

Image Number: 20004

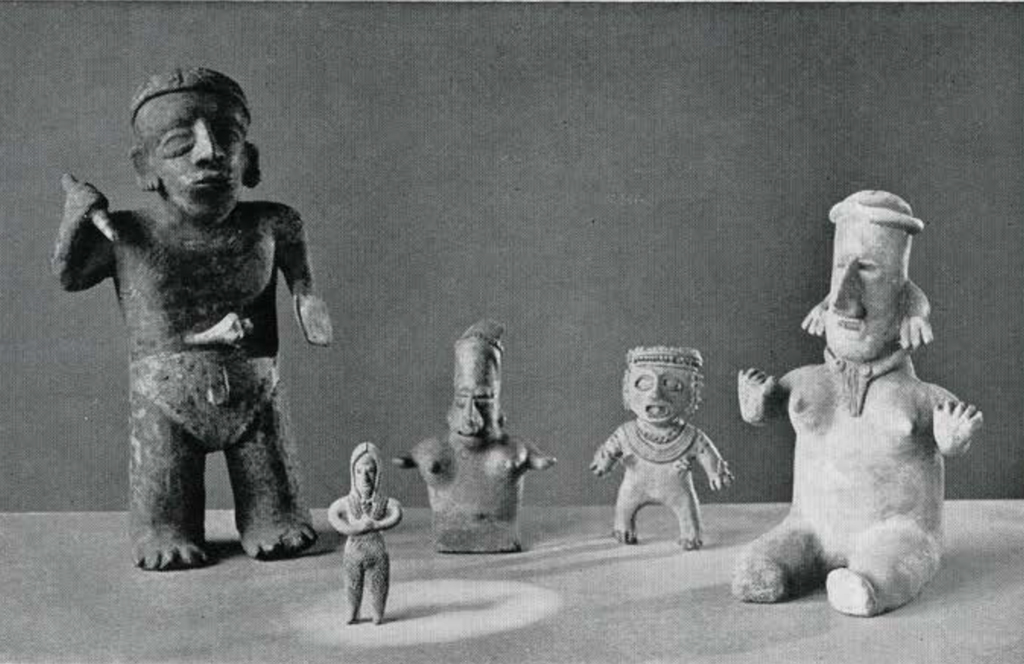

In southern Vera Cruz and western Tabasco lived the Olmec or “Rubber people.” Only a name, and a quasi-mythical one, they have been vitalized by the recent excavations of M. W. Stirling at Tres Zapotes, La Venta and Cerro de las Mesas. A very long period of occupation is indicated, the early stages of which are as old as any in Middle America. Some of the hieroglyphic dates apparently antedate the Christian era, and even at that early date the art was far advanced, the general culture possibly the highest in Mexico at that time. Objects found in the Mexican highlands that show complexes of Olmec characteristics suggest that this may have been the center for the origin and spread of the early theocratic impulses that first appeared in the Valley of Mexico in the Upper Middle Culture. Possibly the Maya, Zapotec, Teotihuacan and other early Mexican civilizations had the same cultural ancestor. Exquisite work in stone carving was done, both in massive monoliths and in small figures, the latter generally of jade. The sculpture is free, naturalistic and equal to the best Maya work; colossal stone heads characterize certain periods and show close relationship to the west coast of Guatemala. Especially characteristic of the art in small objects are human figures and heads with charming infantile faces, and stylized jaguar heads. The pottery figurines are also beautiful and of unusual types. (Figures 27, 28)

Museum Object Number: 15079 / 15080 / 15077 / 15078 / 15076

Image Number: 19977

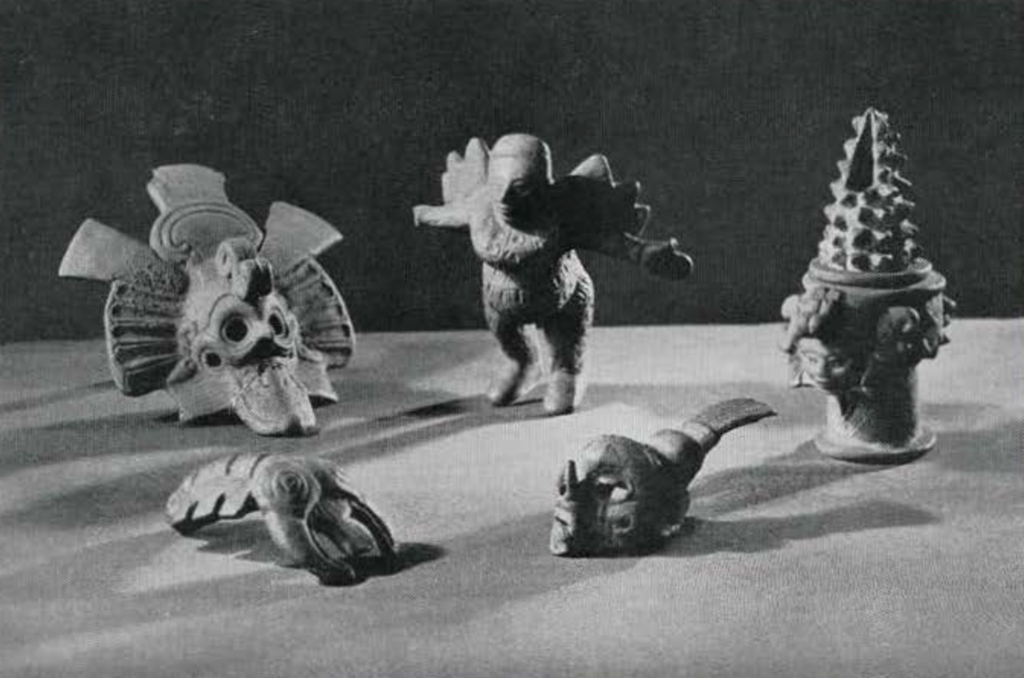

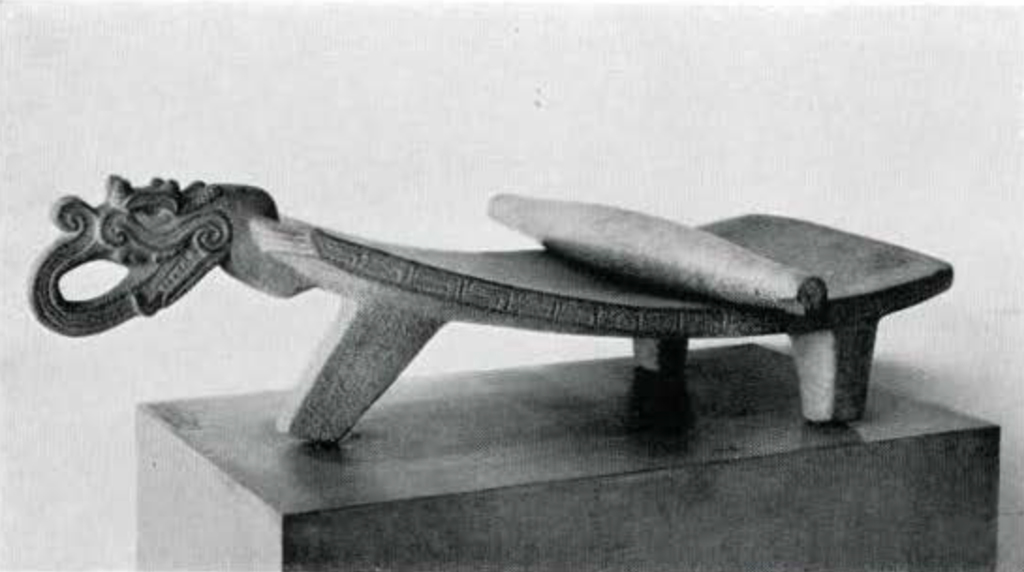

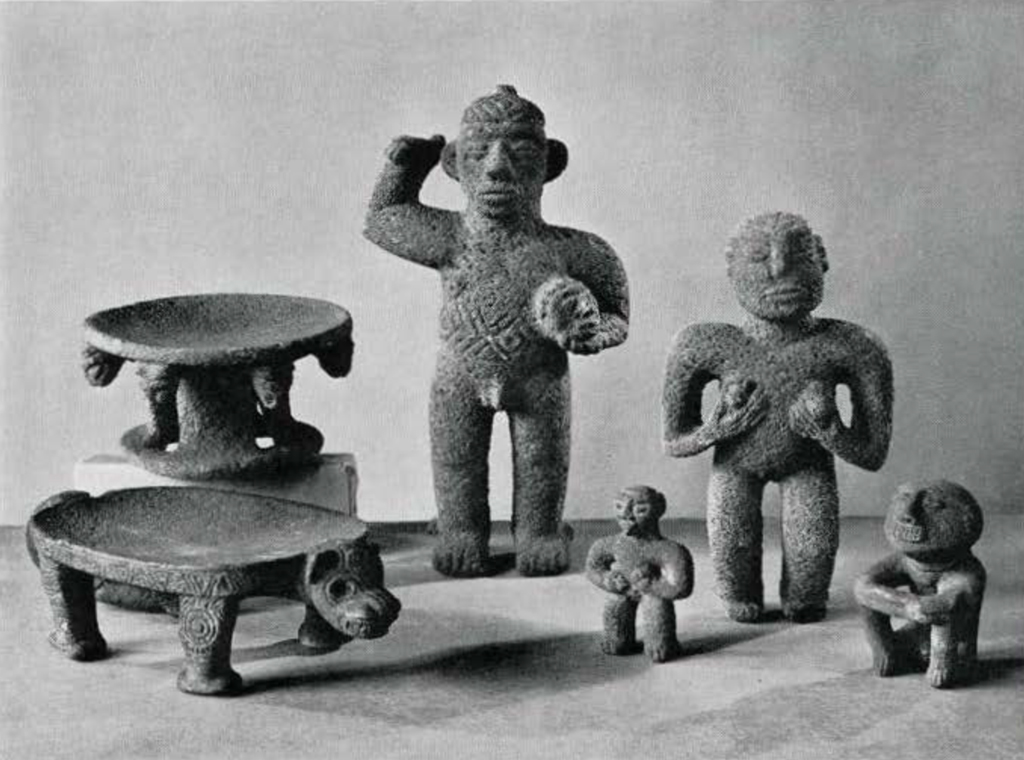

To the north of the Olmec, in Vera Cruz, and between them and the Huaxtec, the Totonac had their center. Their culture was similar to that of the Olmec, but the language was different. They also did excellent work in carving small stone objects, and the ceremonial “yokes” and “palmas” are among the most exquisite examples of ancient Mexican sculpture. The art is generally more conventionalized and stylized than that of the Olmec. Among the pottery products, large human heads showing a most natural engaging and mirthful smile are notable. As in all Mexican regions of long occupancy, the early pottery figurines were hand-modeled, the later ones made in molds. (Figure 30)

The sequential cultural horizons of the Totonac and their country are not so well known. The latest of these was one phase of the generalized Mixteca-Puebla culture, the architectural expression of which is exemplified in the magnificent terraced stone pyramid of Tajin, Papantla, the 364 niches of which each held a small idol.

Museum Object Numbers: 30-53-1 / 20-120-1 / 37-21-3

Image Number: 19973

Museum Object Numbers: 39-29-5 / 42-8-3 / 39-29-10 / 39-29-14 / 12677

Image Number: 20001

Museum Object Number: NA11872 / NA11873B

Image Number: 19501

Museum Object Numbers: 38-29-4 / 38-29-5 / 38-29-7 / 12463

Image Number: 19646