WHY do institutions like our Museum dig out the dead bones of the past? Certainly a prime consideration is often the hope of finding and preserving beautiful or rare objects, and making them known. Even so, an archaeologist is expected to reconstruct the broad outlines of the life and times o the people who produced them – to answer the questions how? why? when? as well as what? Anything, no matter how unspectacular, may be grist for the mill.

Image Number: 20194

If the site is in Middle America, or in the Andean region of South America, rather than elsewhere in the New World, one is better able to reconstruct details of “lost civilizations” because it is then possible to work backward in time from two sorts of non-archaeological sources of information. The white conquerors wrote accounts of native high cultures in these areas, as they were destroying them; and some small native groups went underground and managed to preserve something of the ancient ways of thought and practice, which can be studied today. The old can be interpreted in relation to the comparatively recent past, and even in the light of the present.

In Middle America one of these stubborn modern groups is that of the Lacandone Maya. They are a dying remnant who have retreated before encroaching white civilization, and now live in the otherwise deserted forests south of the ancient ruins at Piedras Negras, in Guatemala. The Museum dug at this ruin from 1931 to 1939, and various notices respecting the excavations have appeared in previous numbers of the Bulletin.

An unusual find was the ancient covered vessel with the peculiar “spikes” shown in fig. 1. We can infer something of its use and meaning by comparing it with vessels still made by the modern Lacandone, two of which are shown in figs. 2 and 3. The uses of modern Lacandone pots like the latter are described in an exceptionally complete study of these people by Dr. A. M. Tozzer, of Harvard (A Comparative Study of the Mayas and Lacandones, published for the Archaeological Institute of America in 1907). He demonstrates that present-day Lacandone religious practices and beliefs are largely survivals from ancient times. Facts concerning the Lacandone culture will here be selected from Dr. Tozzer’s study without further reference to it.

Image Number: 20193

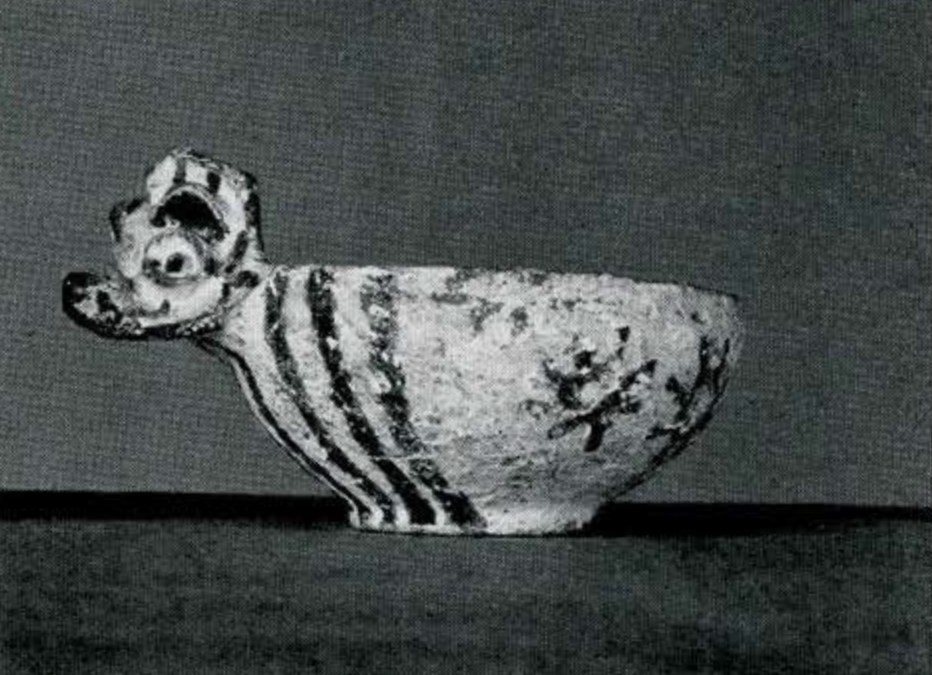

The painted Lacandone vessel of fig. 3 was acquired by purchase some years ago. These people make pilgrimages to the ruins, and leave such vessels behind them. I once saw a number in a room at Yaxchilan, south of Piedras Negras, a month or so after they had been left there. This practice had been noted long before. Whatever else these little pots may be to their makers, they function as incense-burners. Considerable numbers may be used in a ceremony. Fifty, large and small, appear in Tozzer’s plan showing the disposal at a renewal ceremony, though apparently only ten were to remain throughout the year. The incense, a gum usually called copal, is burned in the bowl, and flames and a pungent black smoke rise from it. For the Lacandone, the cloud of smoke is the counterpart of a rain cloud, but it also has magical curative power for individuals, if properly handled. Palm leaves may be waved in the smoke by the head of a family as he chants. Later, he ministers to his family, and “If any part of the body is afflicted, it is tapped and rubbed at greater length with the leaves.”

In the village the ceremonies require a special roofed area or hut which we can call a temple. Here the censers are kept, and also a special clay cover, illustrated by Dr. Tozzer, but not reproduced here. It is more or less hemispherical in shape, with sections of the rim cut or broken out for ventilation, and apparently there was a loop handle on one side which has been broken off. This cover is used for collecting soot from the burning copal gum. It represents the dome of the sky, and the soot is symbolic of the black rain cloud. Indeed, the name of the Rain God, Mensabak, is equated by Dr. Tozzer with “maker of the black powder or soot.” Our little vessel is painted in the manner described by him. The stripes are black and red, on a white chalk base. The black pigment, one understands, must be copal soot.

In fig. 2 we show another Lacandone censer, at the same scale. This was found with others in a roofless palace room at Piedras Negras. They had been placed over debris already fallen from the roof, but were buried by more debris which presumably fell after the Lacandones had left the censers as offerings to some modern god who lived there. The form is very similar to that of the ancient spiked bowl, which was found about a hundred yards away, but below the ancient prepared surface. In essentials the cover of the older vessel is not unlike the modern dome- of-heaven soot collector. Grooves in the handle-like knob at the top form a cross which probably symbolized the four world directions, which figure in the Lacandone ritual, and in that of many other modern tribes. This knob is hollow, with a hole in the top which could be for ventilation. A difference between the modern and ancient bowls is that the older one lacks tiny perforations in the bottom and lower parts of the sides. Such holes, about 1⁄8″ in diameter, seem to be the rule in modern Lacandone censers. But we have one in our collections which has only a single hole, in the center of the bottom; and if there are any at all in the painted vessel shown, they are entirely stopped up by the white paint on the outside, and by remains of the gum inside. Obviously the holes are not functionally necessary for proper combustion.

The correspondence in the form of the spiked bowl is significant, for this combination of hemispherical bowl on a relatively high annular base does not occur in the general run of Piedras Negras pottery. I think no Maya specialist would question that it is an ancient incense burner, as classified by Dr. Mary Butler in her study of pottery at this site. My special point here is that it is good evidence that the modern Lacandone shape and the gathering of the soot may be survivals from times prior to the Maya date 9.15.5.0.0. The spiked vessel was buried before the base of Stela 9, probably erected at this time, when temples were more than thatched huts, and the great period of Maya sculpture was beginning. This might be as late as the Thirteenth, or as early as the Sixth century, depending on conflicting chronological theories. I think the best “scientific guess” is that the spiked censer was laid away sometime during the Eighth Century of our era, quite possibly in the year 736 A.D. A similar form may have been used for a similar purpose for twelve hundred years and more.

Museum Object Number: 44-13-1

Image Number: 20193

The Lacandone make their censers in two sizes, each with similar up-turned faces at the rims. On the larger ones, at least, each face represents a sort of agent-god of a main god, known by name to the priest, though to an outsider all masks appear pretty much alike. The “agent” seems to be essentially a messenger. The masks on the smaller censers represent a lower class of gods or spirits which “are supposed to aid in the general ceremony as additional servants of the gods.” One or several of these smaller vessels belongs to a particular main god. For convenience we can speak of large “messenger” and small “servant” gods and censers. The modern Lacandone example from Piedras Negras was accompanied by smaller “servants” which are not illustrated. Judging by size only, the ancient spiked censer was a “servant.” It is shown at the same scale as the two Lacandone vessels with gods on the rims. It lacks the image, but it seems permissible to imagine that, at the earlier time and place, images were made separately – yet not necessarily divorced from the ritual of the censers. The vessel of fig. 4 shows a censer of similar form. A complete figure is attached, but it could easily have been made to stand separately. This censer was found by the late Dr. Thomas Gann on the surface of a mound in Quintana Roo.

The Lacandone “messenger” censers, visual embodiments of gods and spirits, are normally kept on a special shelf in the temple hut. Some, but not all, may be taken down for a particular ritual. Those which are to participate actively are ranged on a carpet of palm leaves, laid on the floor before the shelf, or on a low table. Those remaining on the shelf are nevertheless near by, and must be, for they are fed at intervals during the ceremony, like those on the altar of palm leaves. Primitive gods do not work for nothing. Food and drink are actually applied to the protruding lower lip of the mask on the censer.

Should these people shift the scene to one of our typical excavated Piedras Negras temples they would find a low masonry bench across the rear of the room, providing a suitable shelf for their clay censer-gods. The altar of leaves could be spread before it, but a new element would enter the picture. This is a short upright stone column inserted in the plaster floor. If the censers, or at least the small servant ones, were arranged close about this column, it would become blackened with soot, and damaged by the heat of the blazing gum; yet the surrounding floor itself need show no effects of the fires. This is the actual situation, found repeatedly. The censer function for the spiked bowl, derived from modern practice, helps explain features in the ancient temple architecture. Clay images of the gods were probably ranged on the long benches when not being especially invoked. Blazing censers to provide black smoke were probably placed close to the column altar during actual ceremonies. Perhaps the image, “messenger” or main god, was placed on the altar itself, where it would be bathed in the smoke provided by “servants” on the floor. In those days there were many temples, and perhaps there was only one master god in a single temple, or two or three related ones.

General correspondence with modern practice may be seen in another feature. A special Lacandone god, Usukun, “is not of good intention,” and has the earthquake spirit for his servant. He alone is excluded from the temple, but is served outside, to the east. At Piedras Negras such unwilling deities could have been fed and bathed in the pungent smoke at a second column altar, set up on the pyramid, but in front of and outside the temple building (though not necessarily to the east).

These burned column altars are present in and before the earliest Piedras Negras temples, so far as we can judge, and they seem to carry the ritual of the incense-burner back to a time long preceding that of the spiked example actually recovered. The Lacandone censers must be renewed periodically, in theory every year. The old and “dead” large censers and the smaller “servant” vessels are then carefully hidden away under the cliffs. Thus it is easy to understand why we find the ancient temple areas bare of the clay idols of which the conquerors spoke. A search for hidden places might be richly rewarded.

The Lacandone have another class of god-image, to which Dr. Tozzer restricted the term “idol.” These are the main gods, and are not renewed. They are carefully handed down from father to son. Each has been obtained only after the god concerned has signified his willingness, and a pilgrimage has been made to his home for the purpose. These gods are little stones, some of them miniature carvings which are undoubtedly the work of the ancients, including what we should be likely to classify as “jade ornaments.” They belong in the bottoms of the “messenger” censers, remaining there below the burning gum, until transferred to a new censer. Such gods as these are by no means absent from our excavated collections, though they seem not to show evidence of contact with fire. They are common enough, but were found carefully buried, with other sacred small objects, in special pots not of the censer class. A common place was below a column altar, which means that many were laid away for good when a new temple was being built. Perhaps these stone gods also died and had to be buried, and new ones made – but at some time interval longer than the year.

Occasionally the collapse of some wall must throw one of these ancient miniature carvings to the surface, where a Lacandone could find it. His obvious interest in these may cause his association of certain gods with certain ruins. We are impressed by dead architectural and sculptural magnificence. The Indian is probably more awed by the gods be- hind it all. For him they are still alive.

L. S. Jr.