In the leading article in this issue of the Bulletin Dr. Rainey gives an account of the Museum’s new project at Tikal with photographs supplied by Edwin M. Shook, whom we have borrowed from Carnegie Institution as Field Director. The 1956 season was necessarily a preliminary one dedicated to opening up the site. When I was invited to fly down for a brief visit I was pleasantly surprised to learn that a fine new carved stela and altar had just been discovered. These monuments fit into a postulated special pattern of assemblage which formed in the back of Shook’s mind while he clashed about the site dealing with more practical matters. The new stela-altar pair is the fifth to be found at Tikal within an “enclosure.” Shook believes that all five “enclosures,” with their monuments, are only single elements in a larger single pattern of assemblage which governed the laying out of all five courts on which the “enclosures” are found. Recognition of this larger pattern. which certainly applies to at least two of the courts, is something new. I leave its description to Shook himself, when he has had time to verify his hypothesis everywhere. I confine myself to an exposition of the chronologic background for a future attack on the problem, and hence to the “enclosures” and their monuments. This requires particular attention to the new Stela 22, and to one of the others, Stela 19.

The term “enclosure” goes back to the great pioneer, Maler, who found three of them more than fifty years ago. I use it in quotes because I agree with Shook that these mounds are probably the ruins of one-room masonry-walled buildings with thatched roofs, the monuments being set behind a single doorway in the south side. We ought to be able to settle this matter by excavation. The placement or Maya stelae indoors occurs very rarely elsewhere, and certainly only at Tikal is there evidence for a whole series of such placements. On the other hand, if there were actually no roofs, placement of monuments within room-like walled enclosures is unique for the area.

The monuments in these “enclosures” are listed below, with the dedicatory dates of the four carved stelae. We may presume that the altars were contemporary with the stelae.

| TABLE: DATA ON MOUNUMENTS IN “ENCLOSURES” AT TIKAL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | “Enclosure” | Monuments | Dedicatory Date |

| D | Structure 72 | Stela 16 / Altar 5 | 9.14.0.0.0 |

| H | Structure 95 | Stela 20 / Altar 8 | 9.16.0.0.0 |

| E | (Unnumbered) | Stela 22 / Altar 10 | 9.17.0.0.0 |

| E | Structure 81 | Stela 19 / Altar 6 | 9.18.0.0.0 |

| E | Structure 86 | Stela E1 / Altar E1 | (not carved) |

The two earliest dates are as given in S. G. Morley’s “Inscriptions of Peten,” and I think are generally accepted. The date for Stela 22 was read by Shook when he discovered the monument last spring. The date for Stela 19 is Morley’s preference between two alternatives, now considered to be sure. For details of these two later dates see below.

The three enclosures discovered by Maler are Structure 72 with its carved stela and altar, Structure 86 with its plain stela and altar, and Structure 81, where he found the carved Altar 6, but missed the carved Stela 19. Shook found this in 1937, as well as Structure 95 and its carved stela and altar, when exploring with others on behalf of Carnegie Institution of Washington. So he was not unprepared to add the unnumbered enclosure and its carved monuments to the list this year, and he is responsible for finding three of the four stelae which can be used to date the ” enclosure complex.” The known chronological “spread” was probably from A.D. 411 to A.D. 790, though some would place this 80-year period earlier in Christian time. It ended 30 approximate years before the dedication of the latest known stela at 10.1.0.0.0 in the Maya count.

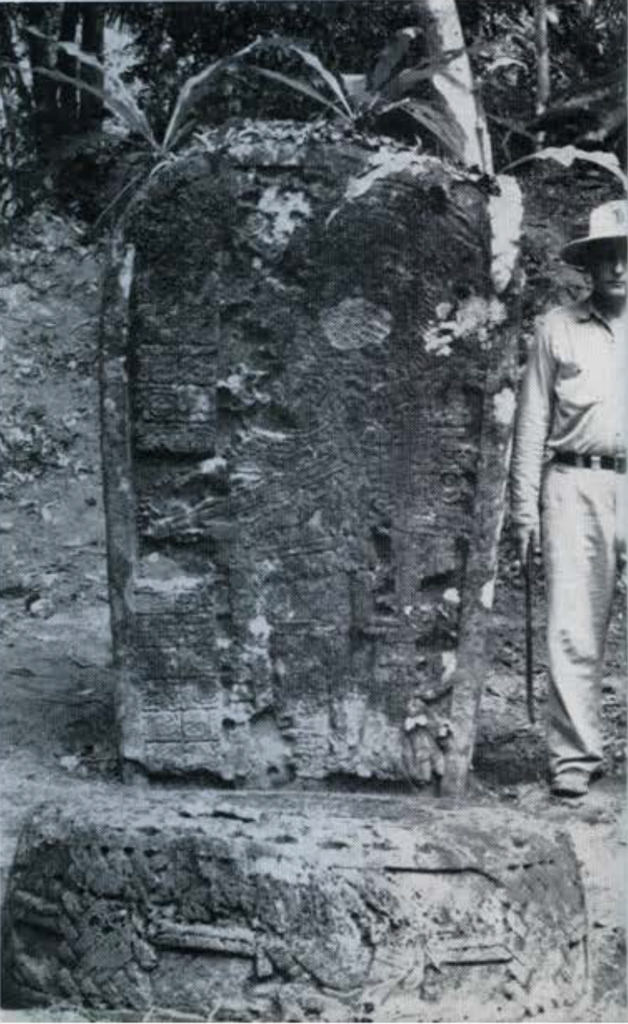

We have stated that one stela and one altar appear in each “enclosure.” This involves correction of a mistake in the published record for Stela 19. which has previously been assigned two altars-a plain one as well as the carved Altar 6. Drawings of the latter appear in Fig. 39. Working in a hurry in 1937, Shook found what seemed to be a second and plain-topped altar, which appears in the foreground of Fig. 35. It is actually the bottom half of Maier’s Altar 6, as demonstrated below, the two halves having been dragged from their original position before the stela. The normal relationship of one altar before one stela seems to have applied within the enclosures as well as elsewhere.

Image Number: 56-3-112

Before turning to details which will not interest many readers, and assuming the correctness of our dedicatory dates as listed, one interesting fact seems clear. The placing of stela-altar pairs of monuments within “enclosures” seems linked with katun-marking, for all four of the known dates are at katun-ends, when one period of 20 approximate years was completed and another began. One suspects that the enclosures, whether roofed buildings or not, were built for the monuments, and so contemporary with them. Excavation will probably demonstrate whether this is so or not. If it is, we have a series of dated similar masonry structures as well as monuments extending through about 80 years of time, from 9.14.0.0.0 to 9.18.0.0.0 in the Maya “Long Count,” and the katun-marker was not merely a monument, but a monument and a structure.

We do not know whether Structure 86, with its plain monuments, belongs before, after, or within this 80-year period. Certainly it may belong within it at 9.15.0.0.0, in which case five sequent katuns were marked by monuments in “enclosures,” without a break in the series. More careful surface examination will probably justify Shook’s hypothesis that the structures and their monuments are only elements in a 5-times repeated plan for an entire court. If this is fully verified we should entertain the notion that for a considerable time each katun was marked by construction of an entire court, basically different from anything earlier on the same spot. Excavation may prove otherwise, but that, I think, is one of the problems we ought to solve. At present it would appear that new ideas in ceremonial court planning had evolved locally, or were introduced from somewhere else.

NOTES ON THE COURTS OF STELAE 22 AND 19

During my visit I made a sketch of two of the “enclosure” courts, the Court of Stela 22, at the east end of Group E, and of the Court of Stela 19, immediately next it to the west. A proper survey will involve significant corrections in the published maps, which do not show the “enclosure” mound of Stela 22, nor the fact that the two courts are clearly separated by a difference in level. The latest rightly shows four pyramids without masonry temples on their tops, and the reconstruction of four stairways on each is fully justified by their forms, but the map is wrong in showing them in three sizes. These pyramids seem to be identical in size as well as form. Two of them, Structures 78 and 79 are in the Court of Stela 22, and the others, Structures 80 and 82, are in the Court of Stela 19. The “enclosure” is to the north in each case, and at court level.

Pyramids of this type are probably unknown elsewhere among lowland sites of the Classical period. Maler called them “sepulchral,” but one had better await excavation before deciding on any specialized function. Whatever the functional implications may be, I was convinced that Shook is correct in thinking that these two courts are substantially identical in size and character.

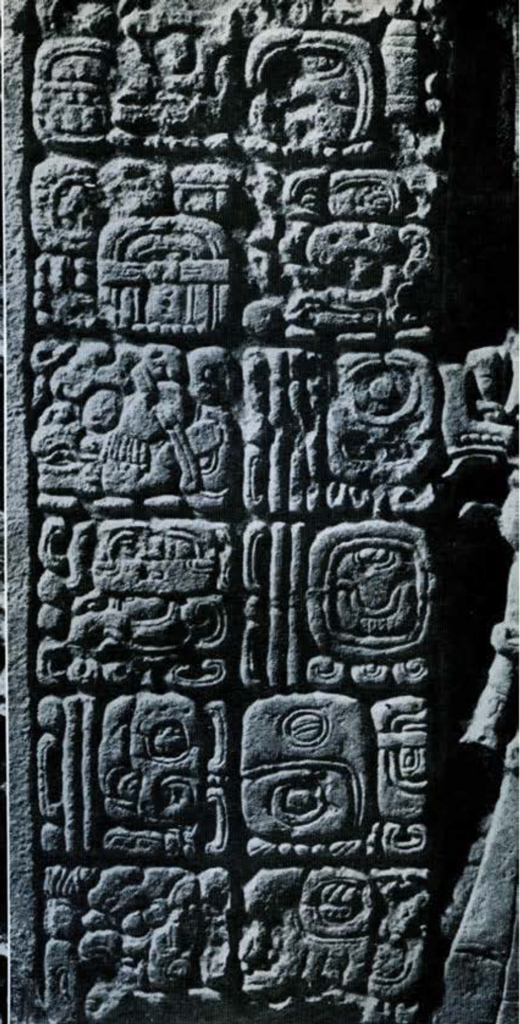

The Dates of Stela 22

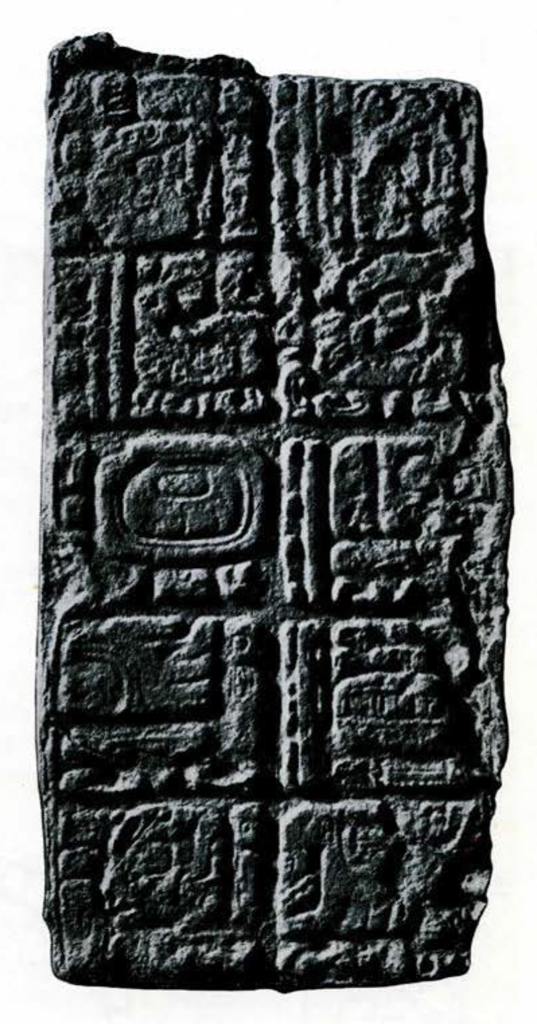

The inscription on Shook’s new stela opens at the top of an upper two-column panel and passes to a lower one (Figs. 33, 34). The photographs, by George Holton with artificial light, are excellent and there is unlikely to be any question respecting the following summary of the chronological portions of the text. As is customary, the columns are lettered A-B, and the rows are numbered 1-12 for convenience in referring to individual glyph-blocks, of which there are twenty-four.

| A1 -B1 | (9.17.0.0.0) | 13 Ahau 18 Cumku |

| A2 | 17th Katun | |

| B2 | Haab (tun) completed | |

| B9 -A10 | 2.1.16 | (distance number counted backward) |

| B10-A11 | (9.16.17.16.4) | 11 Kan 12 Kayab |

It is fortunate that the “period-ending” expression in A2 is clear, for it guarantees the correctness of the distance number, which is partly expressed in an atypical manner. The number is composed of 16 days, 1 uinal (one 20-day period) and 2 tuns (two 360-day periods), which we should express as 756 days. The second term, which accounts for 20 days of this total, is expressed by the moon-sign with a circular “eye” between the horns of the lunar crescent. Unless we read the “eye” as one numerical dot, there is no coefficient such as would appear above a normal uinal sign, had such been used here. The subfix is, however, of the same type one expects in distance numbers. In his great work on the Maya hieroglyphs J. E. S. Thompson discusses various contexts in which the moon-sign is used with the numerical value of 20, finding only five widely scattered examples among distance numbers on the carved monuments. He thought that such use was probably restricted, in all contexts, to 2-place numbers having total values between 20 and 39 inclusive. This sixth example in a distance-number indicates there was no such restriction.

Two presumably chronological glyph-blocks are omitted from our tabulation because their function is not understood. The first, at A5, shows another moon sign with dot-like “eye,” this time with an associated number 9. Like the distance number 2.1.16, it lies between the two dates of the inscription, but in a calendrical sense it is “isolated,” since it seems to be a number, but connects no expressed pairs of dates. Our Dedicatory date is fixed in the Long Count by the “period-ending” method, that is by the brief record “17th Katun” of 82, rather than by the full “Initial Series” Long Count number 9.17.0.0.0, a fact of importance here.

With these shortened “period-ending” statements we do not expect a lunar statement; but after an Initial Series we might have had a whole series of glyphs giving, among other things, the age of the moon, the number of a lunation, and the length of a lunation. Had our glyph at A5 been in the proper place in such a lunar series, we would read as we did in the distance number-we would add the bar-dot number 9 to 20 as the value of the moon sign, and obtain 29 days. But this time the time-distance would be from the end of the last (and the beginning of the current) lunation. We would infer that by Tikal observation (or calculation?) the current lunation was 30 days long, and that on the next 30th day of completion the age would drop to “zero.” Now age “zero” is recorded at Quirgua for this same katun-ending day at 9.17.0.0.0, not for the day after. But in our present imperfect knowledge a disagreement of several days in the moon age as of the same actual day, at different sites, does not cause us to suspect the reading at either site. So one is tempted to suggest that here we have an exception to the general rule that lunar data were never given with mere “period-ending” dates, and that the lunar record was here pared down to the fundamental item, the age-count. The late S. G. Morley has interpreted at least one example at another site in this manner.

The trouble with this hypothesis is that several isolated “lunar” statements like this one have been spotted by Thompson, and in some of them the values as moon ages are far outside the general range of deviations from a standard system of calculated ages used for comparison. If these are moon ages they must be set down as mistakes by the recorders. This could not be a fair way out of the difficulty until the number of known examples giving believable moon-ages far exceeded the number of those which do not. In the meantime Shook’s new stela adds a bit of evidence on a perhaps minor unsolved problem, but one which comes closer to the “egg head” side of ancient Maya culture than many of the findings of archaeology. The mere fact that those Indians could unwittingly set up such a problem for us is not without interest.

Image Number: 56-3-111

The second non-understood chronological block is at B8, where we see a clear “4 Katuns.” Such “isolated” records of katuns, frequently with an affix known as “Ben-Ich” and with coefficients no higher than 6, are, I think, fairly common. Thompson bas considered the problem of their meaning, evidently hopes to solve it, but has not reported that this new example will help.

Every new text is an important contribution to scholars who are trying to learn precisely what was being said about the dates-that is, to decipher the non-calendric glyphs. Those on this stela have been duly registered in a glyph dictionary being prepared by Thompson.

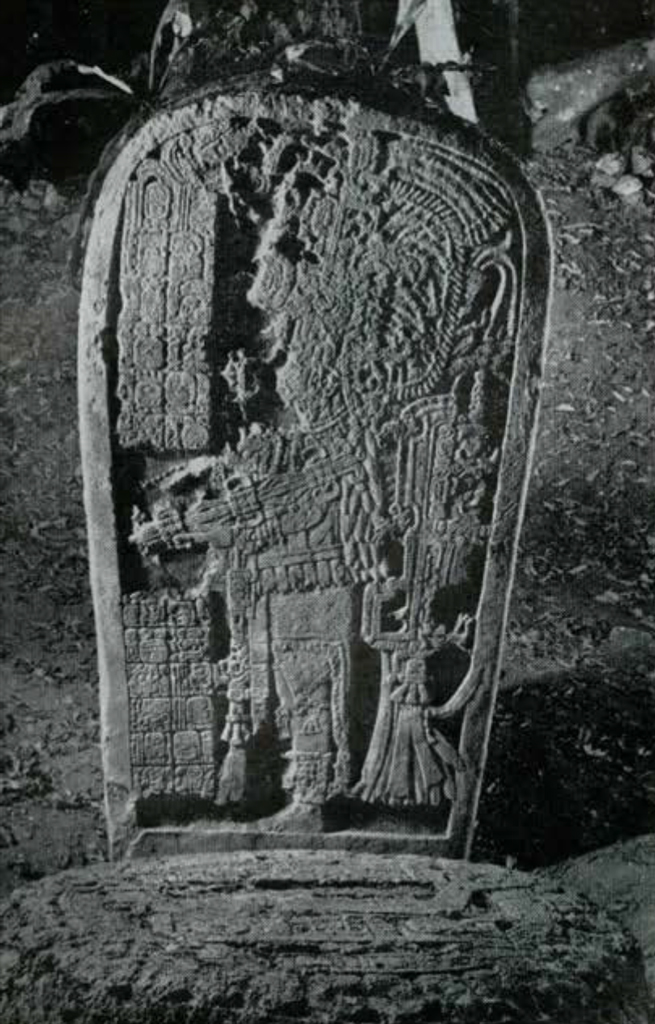

A new monument with well-preserved pictorial design affords a chance to test further the style-dating system rather recently worked out by Tatiana Proskouriakoff, also of Carnegie Institution. Photographs of Stela 22 were submitted to her, and also to Anne Chowning, of Bryn Mawr College, who has familiarized herself with the system. They independently reached the same result – 9.16.0.0.0. plus-or-minus 2 katuns. The stylistically indicated mean date is within l katun of the actual one recorded.

The Dates of Stela 19

Shook tells me that when this monument was discovered it bad to be photographed in the rain, which accounts for the poor photograph published by Morley. Depending on this be was able to read the badly eroded dedicatory date as 9.17.0.0.0 or 9.18.0.0.0, the latter being preferred. With the better photographs of Figs. 37 and 38, or working from the original, I am sure he would have read the rest of the chronologic skeleton of the text differently, concluding that his preferred alternative dedicatory date was surely the correct one. The following tabulation is based not only on better photographs but on study of the original and of casts of the important glyphs, which later can be loaned to interested specialists. The whole design is very similar to that on Stela 22, and here as there one passes from an upper to a lower panel. In this case there are 26 glyph blocks.

| A1 -B1 | (9.18.0.0.0) | 11 Ahau 18 Mac |

| A2 | 18th Katun | |

| B2 | (badly eroded) | |

| B9 -B10 | 1.14.19 | (distance number counted backward) |

| A11-B11 | (9.17.18.3.1) | 2 Imix 9 Kayab |

| A12 | Completion | |

| B12 | Expiriation of 1st katun |

Image Number: 56-5-3

By inspection alone one may say that the day-number in the dedicatory date is above 5 and freak erosion may prevent one from saying it is above 10; the month-coefficient is surely 18; and in B1 where we expect the katun number we have either 17 or 18, with 18 preferred, and this number is above what may be remains of a normal katun sign with a long narrow prefix to the left. Nothing more can be actually seen with certainty in the first four blocks.

Careful measurements show that a symmetrical reconstruction of the coefficient of Imix in the second date calls for two dots between significantly longer elements above and below. The upper of these elements is still there, and while it is not a very satisfactory non-numerical crescent in form, its shape does suggest that it is an eroded one. Thus 2 Imix, rather than 4 Imix as seen by Morley in the poor photograph, is a much preferable reading. Counting forward from the resulting 2 Imix 9 Kayab by the clear distance number reaches 11 Ahau 18 Mac; since this is correct for the preferred katun record at B2 (18th katun) and for the month coefficient of 18 at B1 there now remains no reasonable doubt that the opening dedicatory date was as given in our tabulation. In the actual reading one counted back from the dedicatory date, just as on Stela 22.

I am indebted to Thompson for pointing out the damaged but sure “expiration” subfix in B12, and the somewhat atypical form of his “u-bracket” prefix which changes a cardinal to an ordinal number. The katun sign with coefficient of 1 as main sign is also damaged, but perfectly clear. The signs in this block mean that the count back from the dedicatory katun-end was to a non-tun-end date which was the “katun anniversary” of an unexpressed 4 Imix 4 Zotz, a still earlier date at an unexpressed 9.16.18.3.1 position in the Long Count. This unexpressed date must have bad some special local significance because of which it was taken as the base for a special count which measured its recession into the past, as time went on. We should look for the actual recording of the base-date, and of other “anniversaries” of it, on any new monuments of the late period which may be discovered. With Thompson’s help our re-examination of this inscription adds Tikal to a list of six other sites where he had previously recognized the tun or katun “anniversary” pattern in the calculations.

Image Number: 56-5-3

Using her style-dating system, Proskouriakoff arrives at 9.18.10.0.0, plus-or-minus 2 katuns, for the dedicatory date of this stela. Again the system yields results close to the recorded date, and helps to dispel any lingering doubts as to the reading.

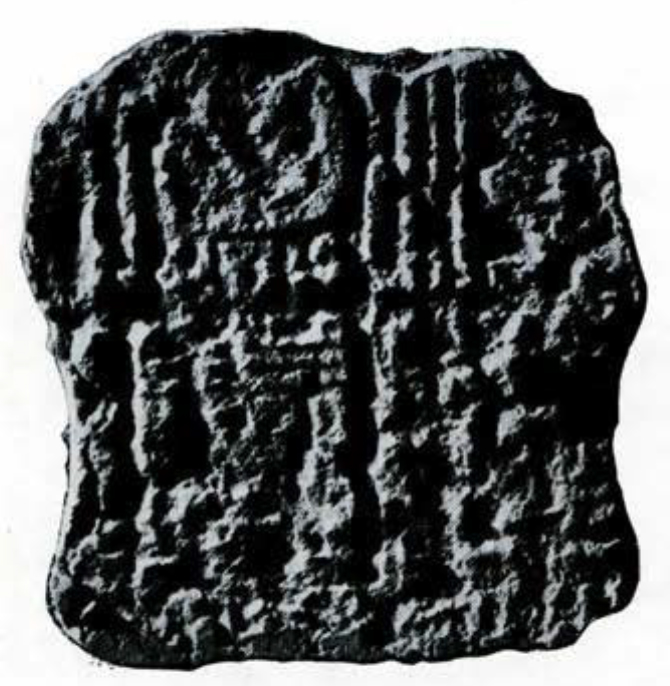

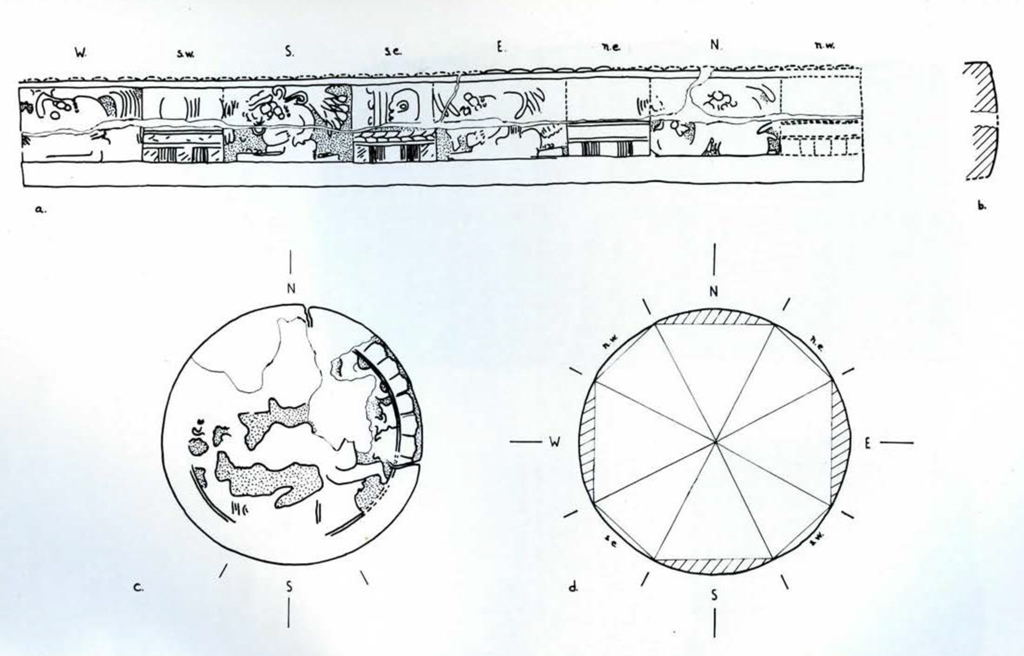

The Design on Altar 6

Maler discovered this monument over a half century ago, but it was in such bad condition that he did not describe it. I made the drawings of Fig. 39 in order finally to dispose of the supposition that Stela 19 was supplied with two altars. The photograph, Fig. 35, shows how easily Shook could be misled in 1937, when he was groping about in the bushes, and in a hurry. When I had cleared up the area for him in 1956 be immediately noted remains of sculpture on the largely buried edge of the supposedly plain altar, and decided that it must be the bottom half of Altar 6, which had split in two. Separate drawings of the edges of the two halves were made and then brought together as in Fig. 39a, and found to match.

There are four panels on the edge showing four seated gods. The bodies are human, shown in front view, while the heads are grotesque and turned to observer’s left, and downward. In some cases, and perhaps in all, the god seems to be gesturing, with one forearm raised higher than the other. Each of the god panels occupies 55 degrees of the circle. The panels which separate them, each covering 35 degrees of arc, seem to have all shown essentially identical basketry objects in their lower halves, but there was variation in what these supported. In the two cases where something is left there is a probable and a sure glyph, the latter being a head with coefficient of 13.

In the drawings, the various panels have been given directional labels, assuming the same orientation before Stela 19 as that of Altar 10 before Stela 22, which had not been disturbed. The four god panels then face to front, rear, and sides of the enclosure, as do the victims on Altar 10; also as on Altar 10, as one stands before Stela and Altar, a victim on the top is seen belly down, arms bound behind his back, his head raised upward and backward, and with one leg also raised up in the air. This type of prone victim may also be seen on Altars 8 and 9, which belong respectively with Stelae 20 and 21, and on Stela 5. Our Altar 6 extends the time range for this trait from 9.15.5.0.0 to 9.18.0.0.0-that is, through most of the known period for “enclosures.” However, only three of the five examples were on monuments in enclosures-Altars 6, 8, and 10. Fig. 39c is my drawing of the top of Altar 6; a photograph of the top of Altar 10 suitable for publication is not yet available.

Image Number: 56-5-4

The diagram of Fig. 39d shows lines joining the ends of the panels on the edge, where they meet the split-off top surface of the lower half of Altar 6. It illustrates the fact that the stone was quite close to a true circle in form, and that the panels on the edge were laid out with considerable accuracy.

I close with a word on the positions in which the two halves were found, that is, as in Fig. 35. Maler first saw the altar “in the center of the enclosure.” This would put it before the butt of the stela, which has fallen backward, and Maler was a careful observer and a stickler for measurements. He says nothing about a sizeable pit in this position, first seen by Shook in 1937, which I filled before the photograph was taken. Tozzer saw the altar and so did Morley and other Carnegie Institution explorers in 1928, without noting a pit and without discovering the stela. It is difficult to imagine anyone missing the stela, once the pit was there, so I conclude that it was dug between 1928 and 1937. Probably “unauthorized persons,” known to have been active at the site during this period, dug the pit seeking a ceremonial cache. To facilitate their operations they probably dragged the top of an already split altar to one side, and the bottom half in the opposite direction.

If this is what happened and the digger happens to read these lines, we would very much like to know if he found anything, and if so, what. We expect to recover a long series of ceremonial caches below stelae and/or altars, but a large majority of them will be associated with plain monuments which cannot be dated directly. One hates to lose the data on a cache which, if there was one, must have been deposited at 9.18.0.0.0.