THROUGH the recent assignment of a greater amount of room to the African collections than was formerly available, it is now possible to show a much larger number of objects in a way which it is hoped will afford a comprehensive view of various phases of the material culture of the negroes and suggest, so far as material objects can, something of the scope of their mental or spiritual achievements in a sphere where art, and religion with its accompaniments of magic, provide the inspiration.

A representation of a noble, as shown by his collar and anklets, presenting a casket. The four half-length figures in low-relief represent Europeans

Museum Object Number: 29-94-3

Image Number: 668

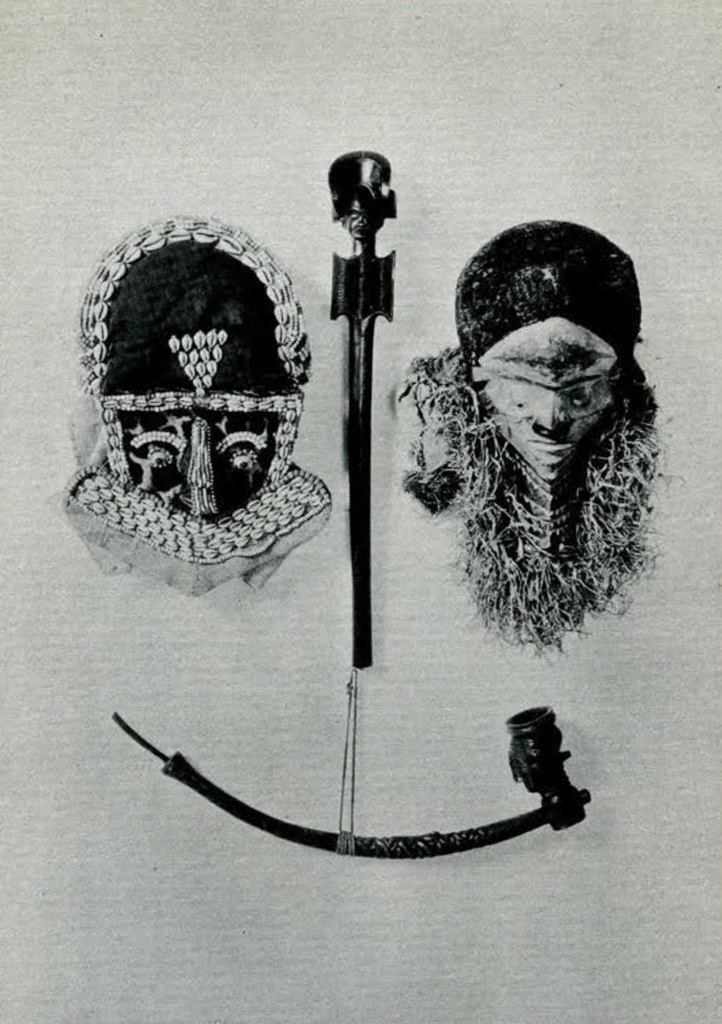

When the installation of the African collections is completed, in the early autumn, the long gallery on the ground floor to the east of the rooms containing the American collections will be given up to collections illustrating the chief types of culture which have been developed in negro Africa. These are arranged topographically, beginning with the Akamba, a Bantu-speaking people of East Africa, who practise both agriculture-of the simple negro form, which does not embody the use of the plough- and the raising of cattle. Then come the Pygmies of the Ituri Forest on the eastern border of the great basin of the Congo. These undersized negroes depend for their subsistence on hunting and the collection of wild edible roots and fruits, insects and small animals. Next, a group of Bantu-speaking peoples, all agricultural, of which the Bushongo are the most important, living in, or on the borders of, the more open forests of the southern part of the Congo basin. Then the Ovaherero, another Bantu-speaking group, a pastoral people of Southwest Africa. Finally, the Bushmen, people almost as short in stature as the Pygmies, who, like the latter, depend for their subsistence entirely on what they can gather-game, small animal and insect forms of life, wild vegetable food-from the country over which they wander-in this case the Kalahari Desert of the South.

The Bushman and the Pygmy collections represent the industries of the only non-Bantu-speaking peoples, with the exception of the Hottentots and Damara, in southern Africa, that is, roughly, the people occupying that part of Africa which lies south of a line drawn from the southernmost point of the great western peninsula to the corresponding point of the eastward projection of the opposite coast-line. ‘Bantus’, if not racially unmixed, are predominantly negro, the ad-mixture with an ancient, probably originally Asiatic ‘white’ race or races, being most perceptible in the east and south. The Bantus of the west, including the Congo basin, have a culture similar to that of the negroes living north of the line indicated above and south of the Sahara, most of whom are engaged in agriculture of the native African type. Though negroes are by no means uniform in race, the culture of ‘West Africa’, in the sense in which this geographical expression is used later in speaking of the art, has considerable uniformity. Negro Africa, for practical purposes, means Africa south of the Sahara, and the more westerly regions of this great area have more in common that is typically negro than they can show of differences.

So there is presented, summarily, a picture of Negro Africa according to the three chief ways of life which have been developed among its peoples in their efforts to make the best of their world in relation to the place in it which they have chosen or to which they have been driven in the struggle for advantageous position. Between the material poverty of the Bushman or Pygmy and the comparative luxury of the settled tiller of the soil the gap is wide and its width is made apparent by observation of the contrast between the simple crafts of the Pygmy and the highly developed arts of a people like the Bushongo. Yet the ingenuity and patient courage required for survival in the hard struggle against discouraging circumstances have made of the little nomads of the forest and the arid steppes beings of character and intelligence not at all contemptible in comparison with the bigger negroes who have reached a more enviable position in human society.

In the room opening from the centre of the long gallery will be seen the fine collections of sculpture in wood, ivory, and bronze or brass. It is in such forms that the spirit of the negro has found its most congenial artistic expression, and it is in the first of the three media enumerated that the negro artist has most often excelled; though, between three and four centuries ago, the metal workers of Benin and Yoruba in Southern Nigeria were employing an advanced technical procedure in the creation of works of high artistic excellence. In this room the artistic products of a number of peoples will be shown, forming, in addition to those placed in their proper geographical relations in the other room, a widely representative grouping of fine pieces from those parts of Africa where negro art has reached its highest development, and which are usually included, from this point of view, under the term ‘West Africa’: the west coast and its hinterlands from Gambia to Angola, together with a large part of the basin of the Congo.

The African collections in the University Museum have been built up during a period of some forty years; most actively during the latter half of that time, under the influence mainly of the late Director, Dr. G. B. Gordon. There is room, even with the larger space now available, to show only a comparatively small part of the material in the possession of the Museum. It has been acquired partly through the generous interest in the Museum of travellers in Africa, partly through purchases from travellers or residents in Africa, either directly or from discriminating dealers into whose hands such material has come. Thus, for collections from the Bushmen and from various tribes in northeastern Belgian Congo, the Museum is indebted to the kindness of Mr. Rodolphe M. de Schauensee and Mr. Alfred M. Collins, respectively, who gathered the material for us during recent hunting expeditions in the regions concerned. The Pygmy collection was purchased from Colonel Wellington Furlong, who lately returned from Africa with relics of Stanley’s expedition for the rescue of Emin Pasha. The Kasai collections were made by the German ethnologist, Leo Frobenius, twenty-six years ago, at a time when the natives of that country were comparatively untouched by European influences, and were added to from the collection of the late Emil Torday, the well-known authority on the peoples of the Southwestern Congo.

Space does not permit either a complete enumeration of donations, like the earlier contributions of Dr. William Pepper or Mrs. W. D. Frishmuth, which have enriched the Museum with valued accessions to the African collections, or a description of the collections themselves. It is believed however that a fair idea of their geographical scope and some notion of their variety can be got from the map, and from the plates with brief descriptive notes which follow here.

H.U.H.

Museum Object Numbers: AF2369 / AF2222 / AF2310 / AF2335 / AF2286

Image Number: 968

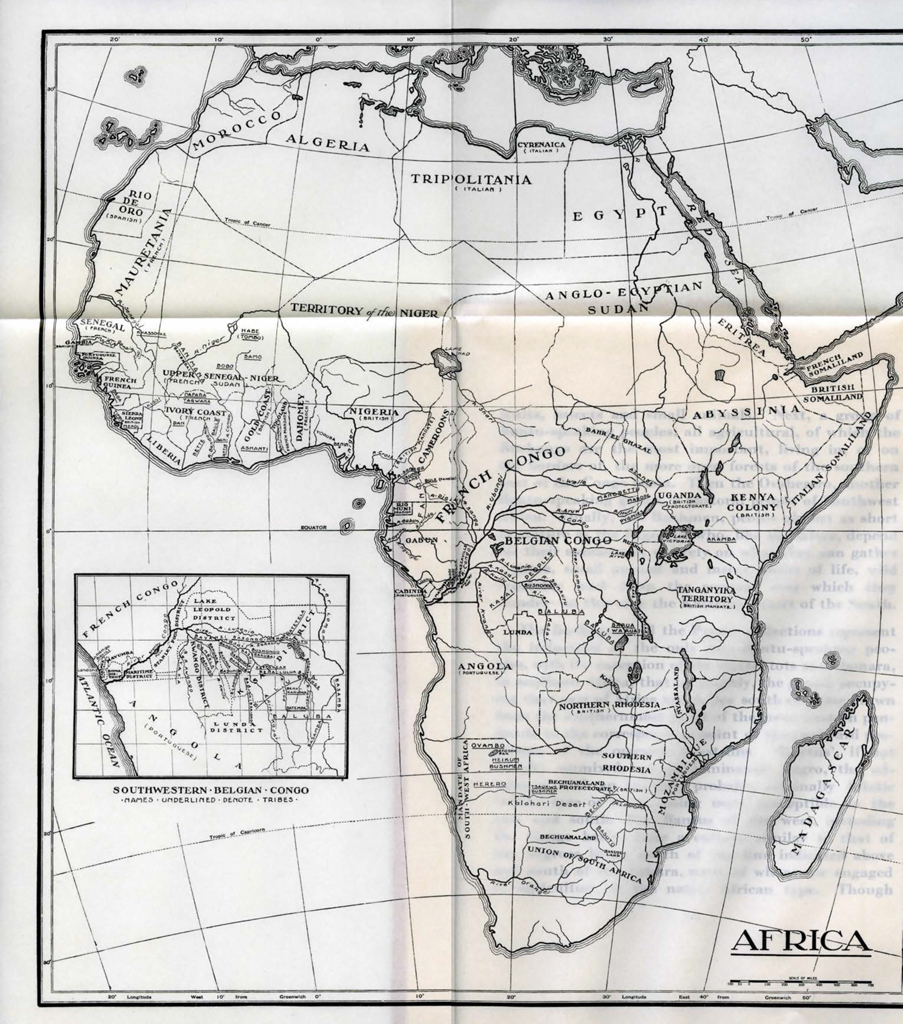

Plate II. Akamba

Primarily an agricultural people, the Akamba have adopted cattle-raising from their neighbours, the Masai. The cylindrical string bag shown on the opposite page is of the kind used by women for bringing in the produce of the fields, the cultivation of which is women’s work. String is made from the fibres of the bark of the baobab and wild fig trees. A hollowed section of a log, marked with the emblem of the clan of the owner, serves as a beehive. Honey is mixed with gruel or porridge, the form in which cassava or manioc, millet, beans, and so forth, are eaten. It also serves to make a fermented drink. The crooked stick with a chain attached is intended to represent the horns of an ox. It was placed on the fence of a cattle pen as a charm to keep lions away from the cattle. The portable stool with its circular top inlaid with copper wire belonged to an Akamba man. Women’s stools have a somewhat different form; men’s stools are tabooed to women. The collar of copper wire is of the type assumed by young men when they enter the class of warriors. The chief enemies of the Akamba were the warlike Masai; raids and counter-raids were formerly very frequent.

Museum Object Numbers: 31-21-9 / 31-21-5 / 31-21-75 / 31-21-53 / 31-21-32

Image Number: 954

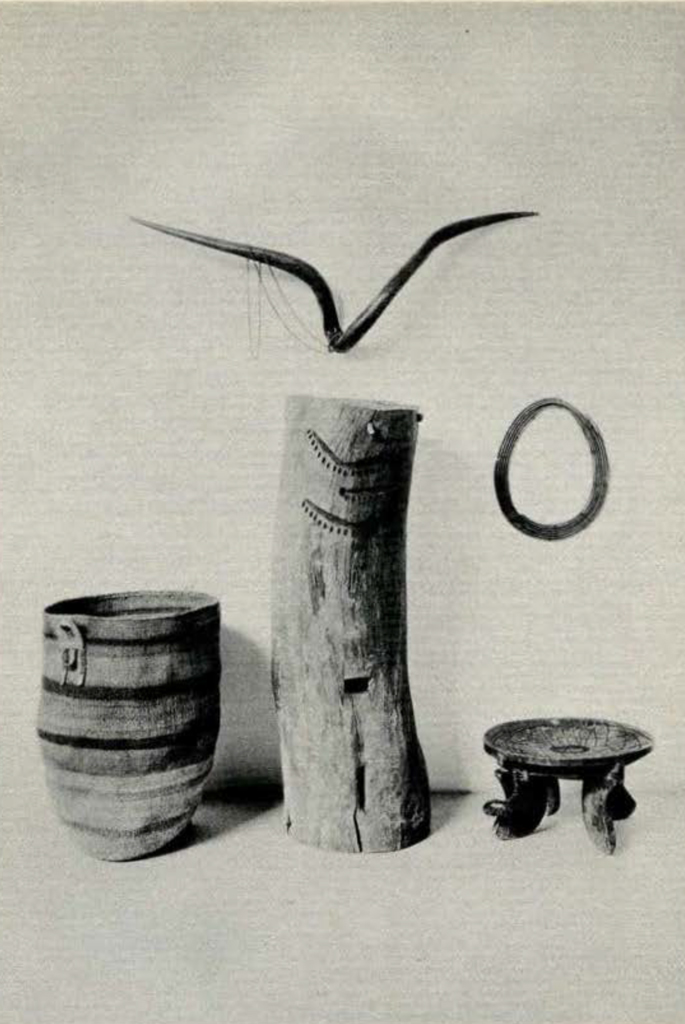

Plate III. Ituri Pygmies

The bow with poisoned arrow is the characteristic Pygmy weapon. The very short bow stave is often reinforced by being covered with the furry skin of monkeys’ tails shrunk on the wood. The arrows are either simple pointed wooden rods-the true Pygmy type-or such rods fitted with socketed iron heads which they procure from their neighbours in exchange for game. Typical clothing consists of an apron made of the felted inner bark of the wild fig; the manufacture of this fabric seems to have been learnt from the taller negroes who have driven the Pygmies into the least accessible parts of the dense equatorial forest. The skin of the okapi, a small species of giraffe, is a favourite material for belts in this region. To preserve whatever of their collections of foodstuffs-game, wild fruits or roots, grubs, mice, and so forth-they do not consume at once-either raw or roasted over or in the fire-it is placed on a round basketwork tray which is hung up out of the way from the roof of the hemispherical shelter of boughs and leaves in which the Pygmies sleep and take refuge from storms.

Museum Object Numbers: AF54 / 29-94-12 / AF3686 / AF5158

Image Number: 840

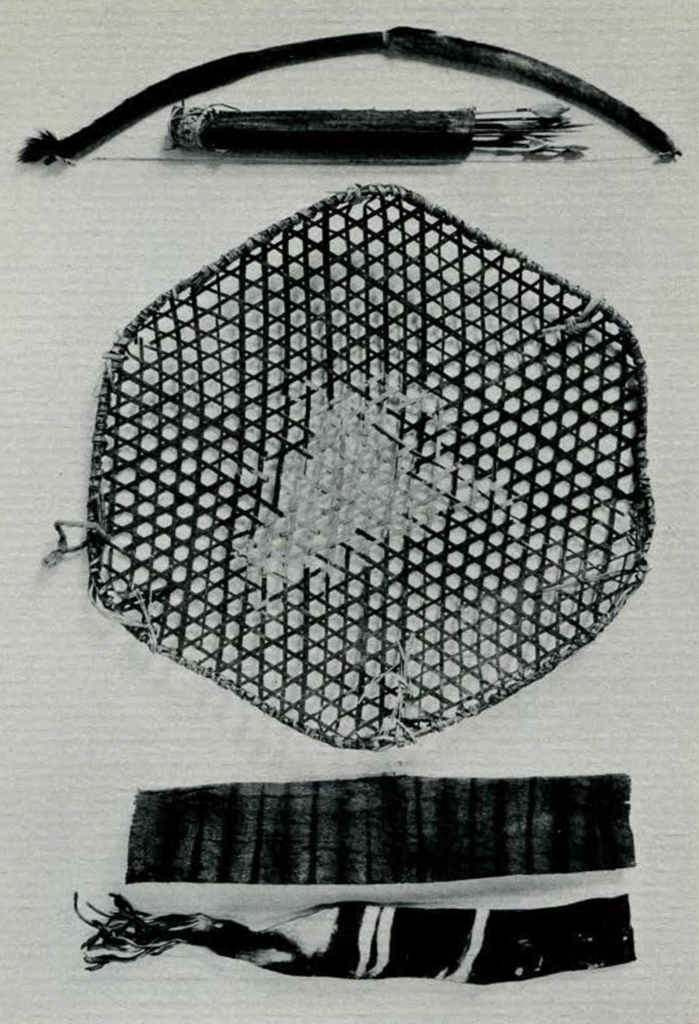

Plate IV. Kasai Peoples

The use of tobacco spread all over Africa with surprising rapidity during a period much shorter than the four centuries which have passed since it was taken by Europeans to the West Coast from America. A Bushongo legend attributes its introduction in their country to their great hero and king, Shambo Bolongongo, who may have flourished some three hundred years ago. The head of the pipe shown opposite represents an antique Bushongo style of hairdressing. The same king is said to have founded a secret association whose members served as a kind of police force. One of three high officials of this society wore the beaded mask made of leopard skin and native palm fibre cloth at the ceremonies held for the initiation of new members into the society. The other mask was worn by male candidates for initiation into adult membership in the Bapende tribe; it was assumed after circumcision, which was performed during the seclusion of the initiates in the bush. The short wand or baton was the emblem of authority of a Badjok (Bakioko) chief. It illustrates one form of a remarkable headdress peculiar to the tribe.

Museum Object Number: AF19 / AF5116 / AF4026 / AF1586

Image Number: 839

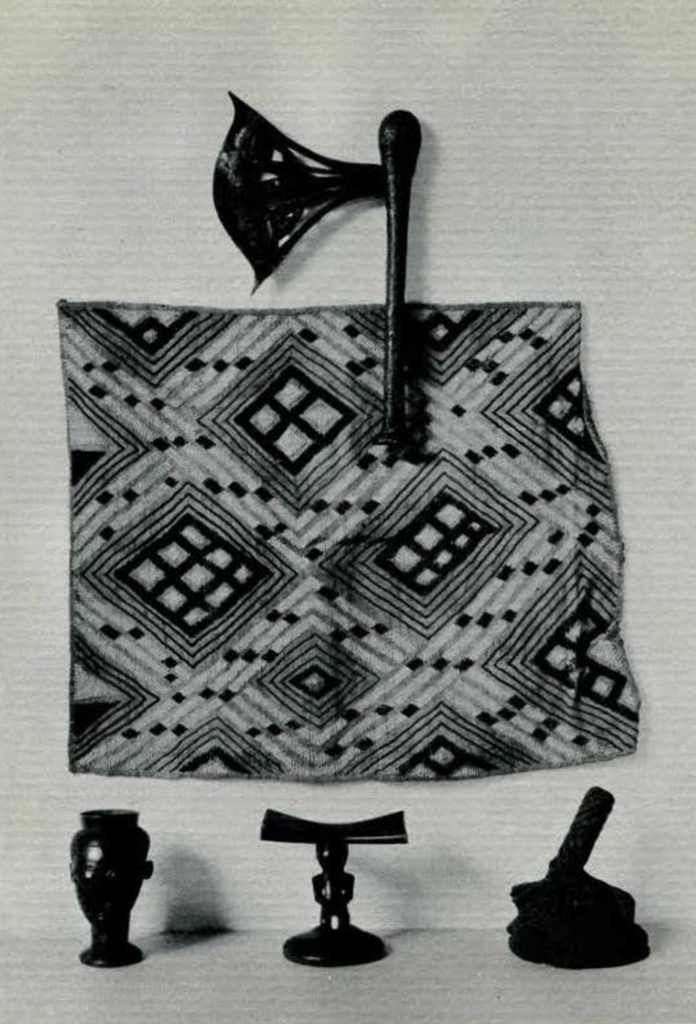

Plate V. Kasai Peoples

The Bushongo wooden cup in the form of a human head represents a conventionalization of the classical style of several large wooden portrait statues which are among the oldest surviving examples of sculpture in wood from negro Africa. The cap of woven string belonged to a Bankutu chief. The wearing of this form of cap by anyone of lesser rank was punishable by a fine. The strip of palm fibre cloth with embroidered design formed part of the gala costume of a Bushongo woman. This kind of embroidery is said to have been invented by the chief wife of Shamba Bolongongo, the hero-king, who, among many innovations, taught these people, as they believe, the art of weaving. The wooden headrest is the African conception of a pillow. This example is from the Zappo-Zap, a mongrel Baluba tribe. These people, who are skilled workers in metal, contributed also the ornamental axe, emblem of the authority of a chief. The blade is forged from a single piece of iron; the handle is of wood, sheathed with copper.

Museum Object Numbers: AF2680 / AF2722 / AF2382 / AF2804

Image Number: 965

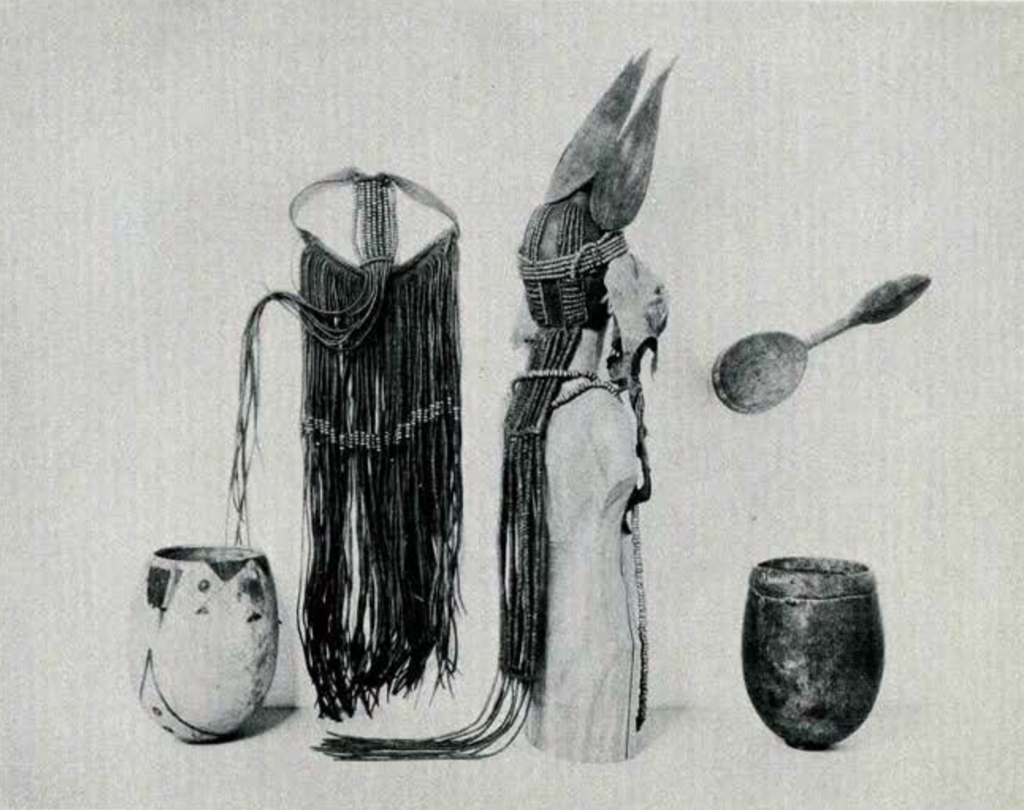

Plate VI. Ovaherero

The headdress of leather ornamented with iron beads is assumed by Herero women at marriage. Beads made of iron or of ostrich eggshell are also made up into necklaces, broad girdles resembling corsets, and leggings, which, together with a pair of aprons and a mantle of animals’ skins, form the married woman’s costume. The apron of thongs decorated with iron beads is worn by girls. The egg-shaped wooden vessels are containers for sour milk, which is the principal food of the Herero, whose whole existence centres about their cattle. The milk vessels are never washed, a condition which ensures the rapid souring of the milk. Men, usually the servants of owners of large herds, tend the cattle on the ranges. Unlike most of those negroes whose chief industry is cattle-raising, the Herero delegate the milking of the cows to the women. In general, pastoral negro peoples-the Akamba providing another exception-forbid all contact with the herds to women, who are believed to have a harmful influence on the cattle.

Museum Object Numbers: 31-2-23 / 31-2-199 / 31-2-167 / 31-2-88 / 31-2-91

Image Number: 963

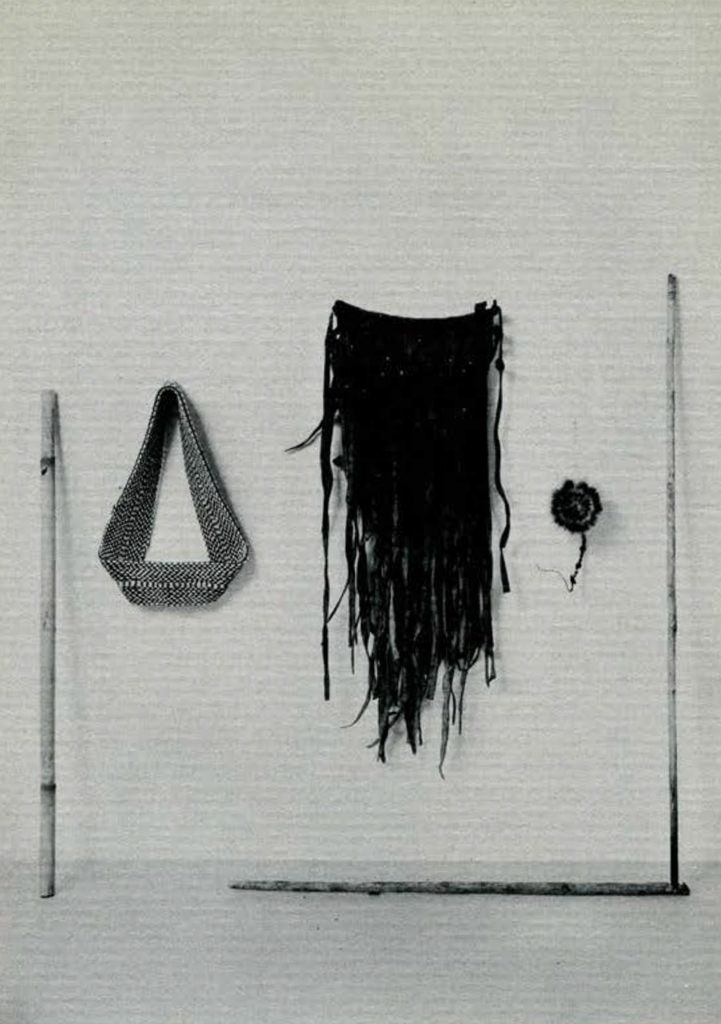

Plate VII. Bushmen

The two sticks placed at right angles were used in making fire; the horizontally placed stick being held in position by a foot of the operator, while the other stick, resting in a depression near one end of the former, was twirled rapidly between the operator’s hands. Heated by the friction, particles of glowing wood dust, falling through a notch in the edge of the depression on to some dried grass, set this on fire. The tube of hollow cane was used for sucking up sub-surface water into the mouth. The water was then ejected through another, smaller, tube placed in the corner of the mouth into an ostrich eggshell held ready to receive and store the liquid, so precious in the arid Bushman country. Bushman clothing is of skins. Ornaments-headbands, like that of a woman shown opposite, necklaces, and girdles-are made of ostrich eggshell discs , the manufacture of which, by women, is the only Bushman industry whose products find a market outside their own territory. The small circular forehead ornament made from the hair of a badger’s tail was worn by a girl. The fringed object is a woman’s apron of thongs. All clothing, the women’s as well as their own, is made by the men from the skins of animals killed in hunting.

Museum Object Numbers: AF5207 / AF5360

Image Number: 875

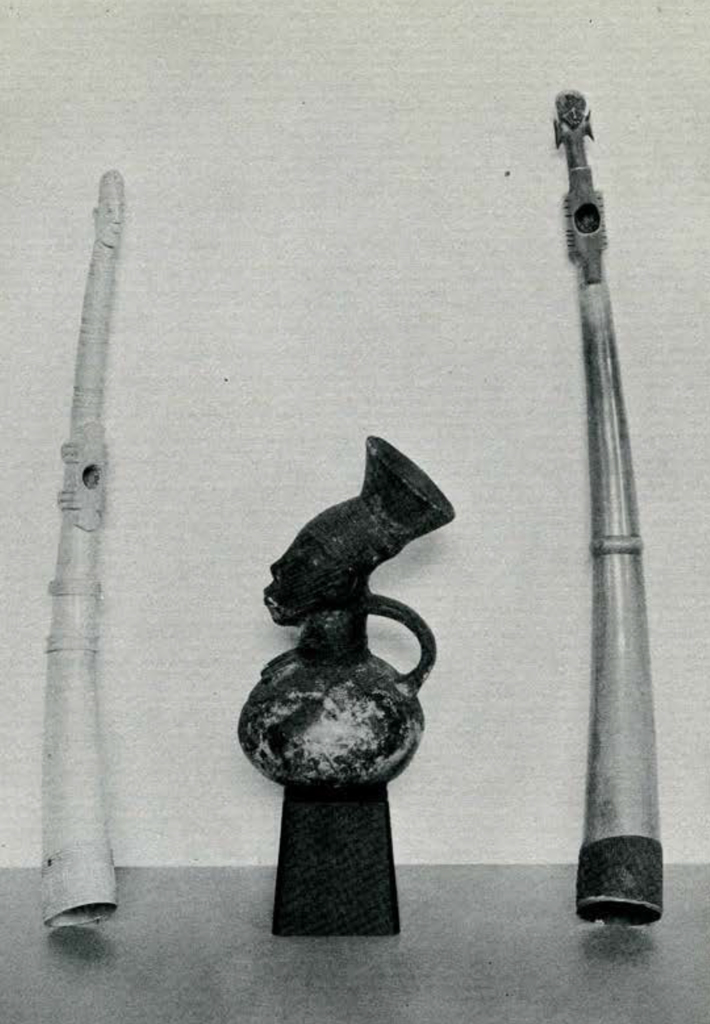

Plate VIII. Northeastern Belgian Congo

The two Mabode ivory trumpets are of a kind used for signalling. They serve also for the amusement of the performer and his audience. A virtuoso is said to be able to produce an astonishing variety of sounds-from the imitation of the soughing of the wind or of the soft pleading accents of the human voice to that of the trumpeting of an elephant! The trumpet on the left if not actually of Azande origin, is due to the inspiration of this more northerly people; the grotesque form of the head which surmounts the other example suggests a local origin. The graceful earthenware jug is from the Mangbettu. The striations on the face of the woman represented imitate the cicatrization or scar-tattooing with which many negroes adorn their skin. The upper part of the jug simulates the elaborate coiffure of Mangbettu women, built up of hair, shed or living, on a cane foundation. This form of vessel is said to be used at the feast which accompanies the ceremonies in which boys are inducted or initiated into adult membership of the tribe; on these occasions the elders drink beer from goblets like this.

Plate IX. Lower Congo and Gabun

The baton surmounted by two seated figures and provided with a fringe of nutshells to serve as a rattle belongs to the equipment of the master of ceremonies in the ritual connected with the initiation of boys. The figures represent the patron spirits of a cult of the rainbow. The figurine at the right is a magic-working image, whose power depends chiefly on the contents of the receptacle on the abdomen of the image. The small iron bell or gong attached to the image serves to summon the spirit or spirits concerned with the working of the apparatus, or to warn its owner of the approach of hostile spirits. The other small wooden figure is of a type which is made as a memorial to the departed and which may be permanently or temporarily inhabited by the spirit of the deceased, which can be induced by sacrifices to help the surviving relatives in time of need. The flat brass-covered image at the lower centre represents a deceased chief or other influential personage. It was kept with the bones of the departed so that his spirit might be summoned by prayer and sacrifices to protect or further the enterprises of surviving relations. It comes from a region to the north of the places of origin of the other three: the basin of the Ogowe River in the French Congo.

Museum Object Number: AF5081

Plate X. Benin

On clay altars in the compound of the King’s dwelling bronze heads, portraits of the kings, were placed, each surmounted by a large elephant’s tusk, which was carved with representations of the divine king, his officials and attendants, European visitors in sixteenth century costume, and so forth. The head with the tusk symbolized the spirits and power of the royal ancestors, or was the seat of those spirits, at any rate during the time of the offering of sacrifices, when animals and human beings were the victims. The human victims were regarded as messengers sent to the ancestral spirits in the land of the dead to convey news of the country and requests for aid and favour from their living representative, the King. The winged headdress was the Bini equivalent of a royal crown, made of coral or agate beads. These were the most prized appanage of the King; besides himself, only nobles and courtiers and their wives could wear the beads, granted to them during their lifetime and reverting to the crown on the death or disgrace of the temporary owner.

Museum Object Number: AF2002

Image Number: 718

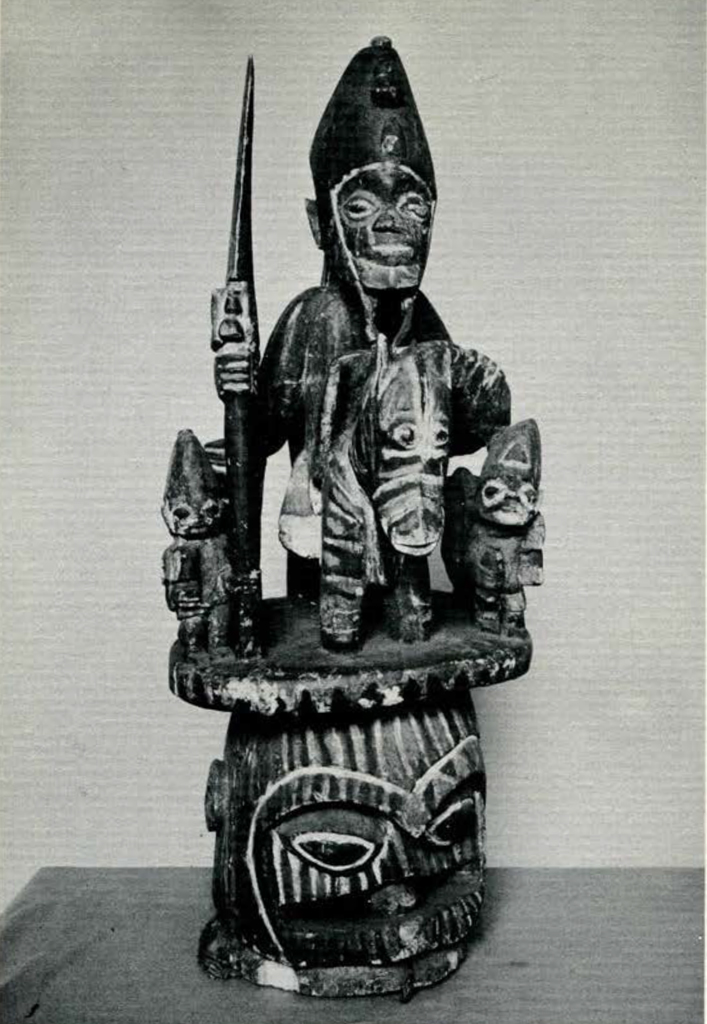

Plate XI. Yoruba

Neighbours of the Kingdom of Benin, who, many generations ago gave to the Bini the dynasty under which their country became a powerful slate, distinguished for the proficiency of its artists, who were equally skilled as workers in metal and in the carving of wood and ivory. They owed much to the inspiration of Yoruba artists, among whose most individual creations were great wooden masks surmounted by large single figures or by groups of figures. The image of a mounted warrior was some-times placed at the entrance of a town to house the spirit of the latter’s guardian.

The group shown here is probably a representation of the god Shango, with attendants whose relatively small size denotes inferiority of rank. The spearhead of the warrior is adorned with the representation of a stone celt between two other objects, probably powder flasks. Another celt is worn on the headdress of an attendant. These celts, whose origin is mysterious to the Yoruba, are an attribute of Shango, god of lightning, and are believed to be thunderbolts.

Museum Object Numbers: 29-12-144 / 29-35-3 / AF5370

Image Number: 722

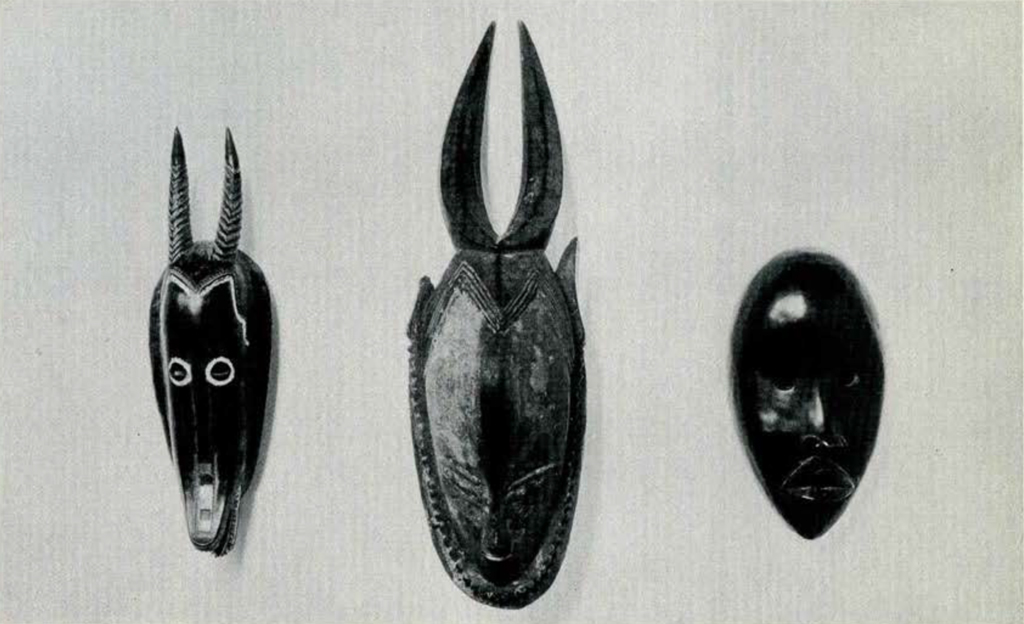

Plate XII. Ivory Coast

The two horned masks are products of the Guro, a people formerly predominant in the western part of the territory now occupied by the Baule, the most important group in the central lands of the Ivory Coast colony. Guro masks are a part of the magico-religious properties of the clan organizations and are made from the wood of trees which have a totemic relationship to the clan or which have magical qualities favourable to members. Clan totems among the Guro, or beings non-human reckoned among the ancestors, include, besides trees, also the goat and the antelope, which may account for the form of the smaller mask and for the addition of goat’s or antelope’s horns to the other. The third mask is of a type found among the Dan of the western border of the colony.