HORSEBACK riding in Southern Mesopotamia in the Third Millennium was not a sport for either gods, kings, or men, because the horse was unknown, and the best and noblest conveyance was by chariots. In that long period from the Early Dynasties in the Fourth Millennium B.C., to the First Dynasty of Babylon at the beginning of the Second Millennium, this was a land of charioteers. Wheels and chariots are the claim and pride of the ancient Sumero-Akkadian culture. Two-wheeled chariots, four-wheeled chariots, with studded tires, curved poles and trappings have been found at Ur and Kish buried with the animals of their team, and even grooms and drivers. A complete copper model with the driver, reins in hand, urging his team of four wild asses, has been recovered at Tell-Agrab. Other examples of war or state chariots are represented on some outstanding monuments: the Mosaic Standard of Ur, the perforated plaque-reliefs of Khafaje and Ur, the Stele of the Vultures of Lagash, and the state chariot of Ningirsu, patron of Lagash described by the patesi Gudea in glorious terms on the great clay cylinder records.1

Museum Object Number: 35-1-16 / B16686

Image Number: 6805

From his account we learn that the four animals of the team were asses of a famous breed called “ug-kash,” endowed with a clear good voice, evidently not horses, as it has been sometimes contended, but a species of equidae related to the wild onager.

A last testimony, a dated account tablet of King Bur-Sin of the Third Ur Dynasty,2 lists 78 teams of asses of all ages and ranks for the town and the country in the royal stables, but no horses.

The mode of driving is characteristic of the time. No bits or double reins were used as is commonly the case for horses in teams or controlled by a single rider. Instead a silver ring was fixed through the upper lips of the two middle asses, and a single line led from the ring to the hands of the driver standing on the box, goad in hand. Oxen and bulls were led in the same fashion by a rope attached to a ring in the nose. Chariots driven by oxen have been found in the trenches of Ur. Mythological chariots3 were drawn by lions or winged dragons (fig. 1).

When the horse was finally introduced into Mesopotamia, it was significantly called “the ass of the mountain,” pointing to its eastern origin. Can we fix a date for its first appearance? The highlands of Persia-the hill regions of the Kurdistan, Zagros, Luristan and Anshan, were the homeland of wild tribes or nations which across centuries invaded and dominated Mesopotamia. The horse was the favorite mount of Parthians, Medes, Persians, even of the wandering Scythians. The Assyrians probably recruited among them their splendid cavalry. The mounted archers of the Balawat bronze doors are shooting arrows while galloping in true Parthian style. The graves of the Luristan valleys, where men and horses were buried together, have yielded a rich spoil of bronze bits, frontals, rosettes and chariot ornaments. In the middle of the Second Millennium the Kassites, descending from the Zagros fastness, dominate Babylonia, correspond with the Pharaohs of Egypt, and send them presents of lapis and horses. The Guti invasion, which destroyed and succeeded the dynasty of Agade in the middle of the Third Millennium, brought perhaps the first “ass of the mountain,” or horse, into Mesopotamia.

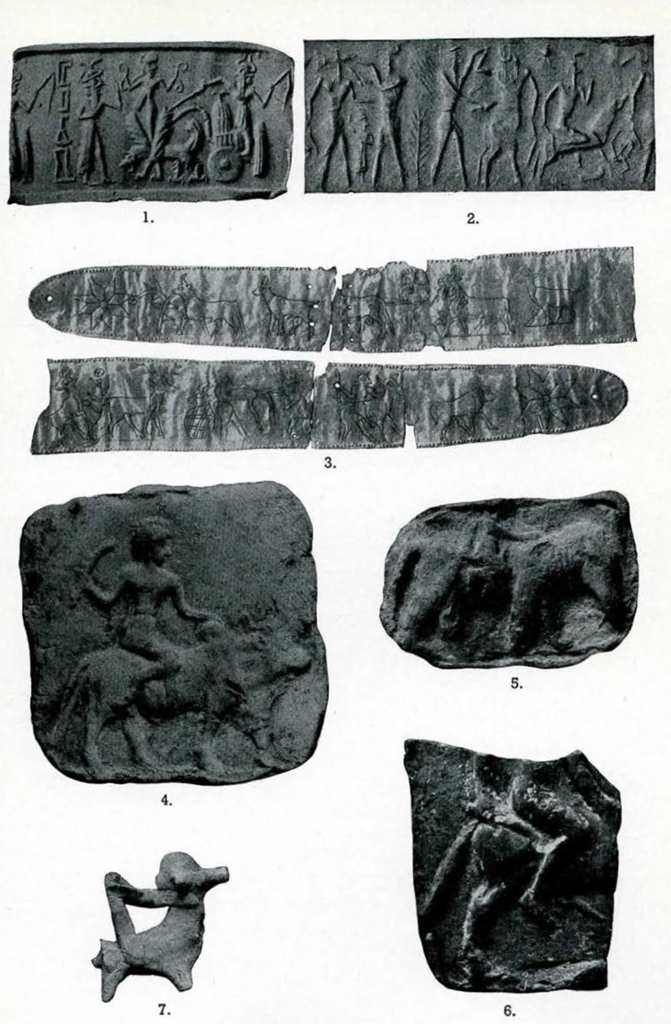

The rare examples of horseback riding in that period are found on two stone cylinder seals of the Post-Sargon type, and on a gold fillet discovered at Ur in a grave of the Royal Cemetery, also dated in the same Sargonic age. To these may be added now three reliefs on clay plaques, two from Ur, and one from Ishchali (reproduced with the gracious permission of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago), which represent men riding astride not only a horse, but a typical Indian bull, and even an elephant. The style of riding is very peculiar. The plain of the Diala, where Ishchali is located, is rich in Indian monuments. It is the natural highway of the land trade from the Eastern regions towards Mesopotamia. An Indian seal, found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, shows that such a trade existed in the early part of the Third Millennium. The reliefs here presented are a new link in that chain of evidences. They are:

- Cylinder seal of carinated black diorite.4A rider, whip in hand, astride a curious animal. He bears an Akkadian name: Na-ti-um servant of Lugal – an-na-tum. A Lugal-annatum, ruler of Umma, was a contemporary of Sium, King of the Guti (Plate IX, No. 1).

- Cylinder seal of carinated black marble5 (No. 2). The same horse- back rider, whip (?) in hand, gallops away over the body of a prostrate foe begging for mercy. He is riding in a peculiar style with bent leg and high knee. The rest of the composition shows solar heroes defeating their enemies, one of which is Eabani the bullman.

- The gold fillet from Ur6 (No. 3). This was tied about the head of a lady of quality, buried in a grave of the Sargonid age with her necklaces, pin and cylinder seals. Haphazard figures have been impressed on the soft metal: hunters, bearded men with long hair, holding rope or lasso, wild animals of the hill country, bearded bison, antelope, red deer, goat in a net, mastiff, and among them the same identical rider on horseback, whip in hand. The impressions were often weak, and some question might be raised about the position of his leg and knee.

- The rider on the back of an Indian bull.7 (Ishchali, Iraq. By permission of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago. (No. 4).

The animal is a splendid example of the Bos Indicus, drawn by an artist from the living model, with all the details of hump, horns, dewlap, and passive gait. The mode of riding is especially interesting. The driver sits astride, with bust and face turned sideways, his raised right hand brandishing a short slightly curved club over the hind quarters of the bull as if ready to strike; his left has a good grip on the hump. A large strap of some woven material is tied round the body of the animal, loose enough to allow the knee of the rider to be stuck below in order to keep his balance. - The elephant and his driver8 (No. 5).

This curious relief, found at Digdiggeh near Ur, is evidently the work of an artist not familiar with elephants, or the proper way of driving them. It would be difficult to do him justice without reference to some model new and strange to him like the rider on the Indian bull. His elephant, anyhow, is true enough to be identified with the Indian type: straight back, square head, small ears, thick stout legs (The Komooria Dhundia).9 The tail is somewhat long; no tusks show, and it may be a female, its trunk rolled up as if collecting fodder, its hind leg raised, which is the natural gait of the huge beast while marching.

But the driver-the Indian mahout-is here represented in an impossible position, sitting neither on the head nor on the neck, but hanging mid-flank on one side, his left hand resting on the shoulders, his right, armed with the short curved stick, simply hanging motionless. Fortunately the big strap tied about the body of the animal, and under which he has stuck his bent knee, helps him conveniently to keep his balance, as it does more naturally for the bull driver. Such straps are still used today in India to keep the howdah in position. - The horseback rider10 (No. 6).

This fine example of the Sargonid art is unfortunately broken. The heads of both rider and horse are missing. It was evidently modelled from life by an artist with the ideal of the Greek sculptor for lines and proportions, the play of muscles and motion. The horse is unmistakable from hip to hoof. Only one back leg is seen in perspective as if the animal was galloping. The rider, slightly bent forward to follow the action of his mount, is not sitting straight close to the shoulders, facing forward, both hands controlling the reins, as usual with later figures of Persian riders. To the contrary he follows the foreign style exemplified in the previous reliefs. His bust is turned sideways, the left hand resting on the neck of the animal, the right arm half bent, the right hand over the tail of the horse grasping the stick or whip. His two legs are hanging normally, the second foot showing in perspective below the belly of the horse. The only strap is again the large woven band we have seen about the bodies of the Indian bull and of the elephant. - The rough rider11 (No. 7).

In contrast with the riders in intaglio on the seals and on the gold fillet, or in smooth relief on the clay plaques, there is a small horseback rider, roughly modelled by hand in the round, a work of the local potter which betrays a very different skill and inspiration. It is essentially a sketch, a symbolic figure, not concerned with anatomic details and even true proportions. The most successful parts are the horse’s head and neck. The legs are too short, and the hind quarters are curiously flattened, leaving a little clay projection to attach it to some other object-perhaps a clay chariot. A rough piece of clay serves for the body of the rider. There is no attempt at modelling. The piece is split below to represent the legs, but these are left unfinished below the knees. The head is missing, but from other examples we know that it was of the archaic type with pellet eyes on either side of a sharp nose pinched out of the clay. The arms are shapeless pieces of clay of exaggerated length to connect with the hands clasped about the neck of the mount. This is the all important gesture of the rider planted stiff and too far back over the hind quarters of the horse.

Such is the so-called snowman technique of a potter using fingers and clumsy tools very different from the refined, delicate work of the seal maker and engraver on hard stones. Moulds of clay were later used to multiply good originals, made of baked clay or even stone. But still cheap products were modelled by hand to meet a popular demand in all places and times. This is the case of the Persian horseback rider, a well-known terra-cotta model with which our rough rider has much in common, notably the rider’s position with hands clasped about the neck of the mount, and the horse’s erect neck and small pointed head with pellet eyes, and a mane cut in a brush between short ears.

In reality the archaism of the rough rider sets him apart from the Persian rider, who usually wears the Persian pointed cap and beard, and sits quite close to the neck of his mount. The horse evidently changed less than the rider, from the faraway days when the strange “ass of the mountain” appeared in the plains of Mesopotamia with a man astride its back, coming from the highlands in the East. In the Third Millennium it was still a rare vision. Later they would pass as a torrent.

“Behold a people shall come from the north . . . , they shall hold the bow and the lance . . . , and they shall ride upon horses, everyone put in array like a man to the battle, against thee, O daughter of Babylon.”

(Jeremiah, Chapter L, Verses 41-42.)

L. L.

1 The Gudea Cylinders A.VI, 18; B.IX, 15-16, XIII, 18. For a translation of the inscriptions see; George A. Barton, The Royal Inscriptions of Sumer and Akkad, Yale University Press, 1929. ↪

2 L. Legrain, Le Temps des Rois d’Ur, Paris, 1912, v.1, No. 43. ↪

3 Seal cylinder of black steatite from Ur, found in a pit of the Royal Cemetery labelled PJ (Predynastic Jemdet Nasr), in the grave G.99, and registered under the field number U.18922, now in the University Museum (CBS 35-1-16). It shows a god driving a chariot, drawn by winged dragons. Between the wings rises a goddess armed with curved bows. Inscription to the name of Ur-giš-me-è, see: Antiquaries Journal, XIV, 1934, pl. XLII. ↪

4 L. Legrain, The Culture of the Babylonians, (In University of Pennsylvania, University Museum. Babylonian Section. Publications. v. 14, 1925, No. 154). The seal now in the University Museum (CBS 5028), was bought in Baghdad in 1890. ↪

5 Collection De Clercq. Catalogue Méthodique a Raisonné, Paris, 1888, v. 1, no. 181 bis, pl. XXXVIII. ↪

6 Joint Expedition of the British Museum and of the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania to Mesopotamia. Ur Excavations . . . The Royal Cemetery, London, 1934, v. 2. Text, p. 299 and Plates, no. 139. The Gold Fillet registered under the field number U.8173 and now in the University Museum (CBS 16686) was found in the grave PG. 135 (predynastic graves). ↪

7 University of Chicago, Oriental Institute. Oriental Institute Communications, No. 20, 1936, fig. 73c. (photo. 25859). ↪

8 Ur terracotta, registered in the field U.18819. It was found in the Digdiggeh Cemetery outside of the city. In the forthcoming volume on Ur Terracottas, it is catalogued under No. 378. ↪

9 E. J. H. Mackay, Further Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro, Delhi, 1938, v. 1, p. 329. ↪

10 Ur terracotta, registered in the field U. 18819 (in the forthcoming volume it is catalogued under no. 392). It was found in the pit of the Royal Cemetery labelled PJ at level 16th below the surface. ↪

11 Ur terracotta registered in the field U. 6892 (in the forthcoming volume it is catalogued under no. 36). It was found in the Digdiggeh Cemetery outside of the city. ↪

PHOTOGRAPHS

- Mythological chariot. God driving a team of winged dragons, Goddess standing over them-Cylinder seal from Ur.

- Horseback rider-Cylinder seal in the De Clercq Collection.

- Horseback rider, on a Gold fillet from Ur.

- Rider on the back of an Indian bull, from Ishchali. Terra-cotta.

- Elephant and its driver. Terra-cotta plaque from Ur.

- Horseback rider. Terra-cotta plaque from Ur.

- Horseback rider-Archaic hand-modelled type from Ur.