Brief accounts of the excavation and a reconstruction of the throne room of the Merenptah palace at Memphis have already appeared in the pages of the JOURNAL (Dec., 1917, and Mar., 1921). In view however of the preparation of a large scale model of this gorgeous chamber which will form part of the exhibit in the new Egyptian wing of the Museum, it seems well at this time to give a more detailed account of the decoration.

The chamber had been ruined when the palace was burned shortly after the death of Merenptah, and the heap of smoldering woodwork from the ceiling and doors had baked the greater part of the floor a bright red and wholly obliterated the pattern on its delicate covering. Since then the gradual rising of the bed of the Nile for many years has caused the palace level to be more and more submerged during the annual Nile flood. When excavated the floor consisted of soft sticky mud, on which only the traces of the bricks owing to the lighter lines of the joints, could be detected. The floor had been first paved with one course of large sundried bricks resting on a thick bed of sand. The surface had then been levelled up with a thin coat of mud mixed with cut straw. Over this was a smooth coat of white stucco giving a finished surface for the artist’s drawings. The decoration of the raised stone dais supplied the motive for the decorative scheme as, from one small fragment in one of the adjoining chambers, it was certain that borders of lines and dots like those on the dais were used on the floors. From a design on the floor of a similar royal apartment at El Amarna, we can supply the missing details.

From the main door to the foot of the ramp was a wide strip divided into transverse panels, each with a figure of a captive or a single bow. The captives all faced towards the door but their heads were placed alternately towards the right and left. There was here probably only a single row of captives on the main floor instead of a double row as on the ramp. Along each side of this band was a border of rakheet birds with upraised human arms symbolic of all peoples, adoring the king, within narrower borders composed of simple bands of red and blue and a row of discs, those with red rims having blue centres and vice versa. This motif filled the main aisle. The spaces between the columns and the outer walls were given up to marsh scenes, with various water fowl disporting amidst the lotus blossoms. The whole floor was enclosed in a composite border of simple bands and discs as in the central division. This richly colored covering would have had the appearance of a beautiful carpet.

The dais upon which was placed the chair of state stood at the far end of the room. It was of limestone raised twenty inches above the main floor and approached by a slope but slightly narrower than the outer end of the dais itself. The decoration on the ramp and dais was cut in low relief and colored like the floor. There were panels of captives with bows surrounded by a wide border of rakheet birds, rows of discs and simple bands. At each side was a block of stone cut to form four steps each with a sunken panel containing a captive or double bow. There were traces of gilding overlying the red bands and it may be that in every case red was simply the basis for the gold leaf.

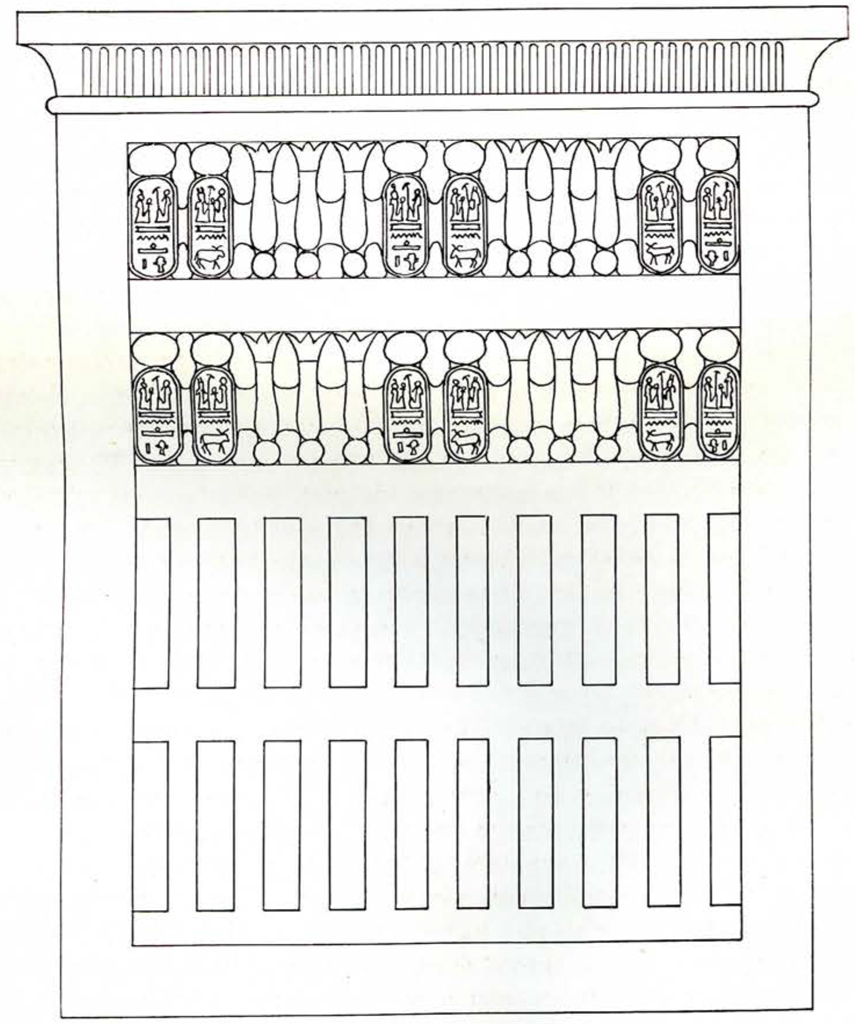

The walls were finished in the same way as the floor with a final fine coating of white stucco. At no point did they remain for a greater height than six feet, so that we have only the material for a restoration of the lower portion. This dado was divided into horizontal strips. The lowest had a series of painted offering niches with spaces between sufficient to contain a bunch of lotus or papyrus plants, the respective emblems of Upper and Lower Egypt. Above this was the usual charming narrow border of red, green, yellow and blue blocks. Then came at least two rows of cartouches bearing the double names of the king between the ankh and uas hieroglyphs meaning life and happiness. This brought the decoration to a height of about eight feet. Between here and the ceiling the wall space may have been filled with similar bands of cartouches, but from the inner faces of several of the doorways I am inclined to think that it contained more spirited pictures, such as the king hunting and fishing or perhaps, to follow out the idea uniformly expressed on the columns, scenes showing the king making offerings to Ptah, or slaying his enemies. The windows were placed high up, four along each side, corresponding to the spaces between the columns and possibly two at the rear wall on either side of the throne. Each window was cut from a single thin slab of limestone and one has been restored from fragments found lying just outside the walls. It was divided into four horizontal parts, the upper one having a pattern of three groups of double cartouches separated by kheker ornaments. In the second division were similar cartouches but separated by winged hawks. The lower two divisions contained rows of simple open slots. The spaces between all these were perforated. The entire surface of the windows was either colored in harmony with the wall decoration or was completely gilded.

The roof was divided into three main panels by the long wooden girders of cedar wood resting on the two rows of columns. These had inscriptions similar to those on the doors and columns, painted with dark green and blue on a reddish ground. The transverse rafters rested on these at intervals of three feet and were likewise painted red, while the ceiling spaces between them were colored a brilliant blue studded with golden stars to represent the heavens.

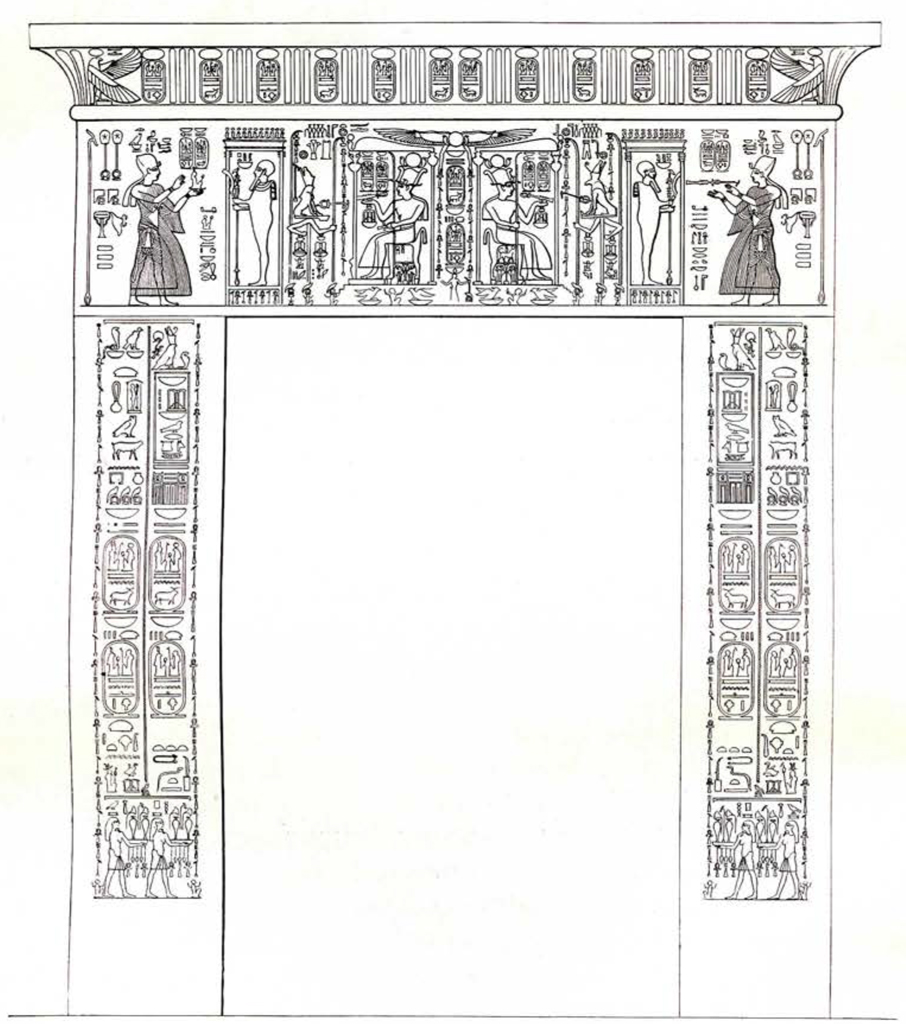

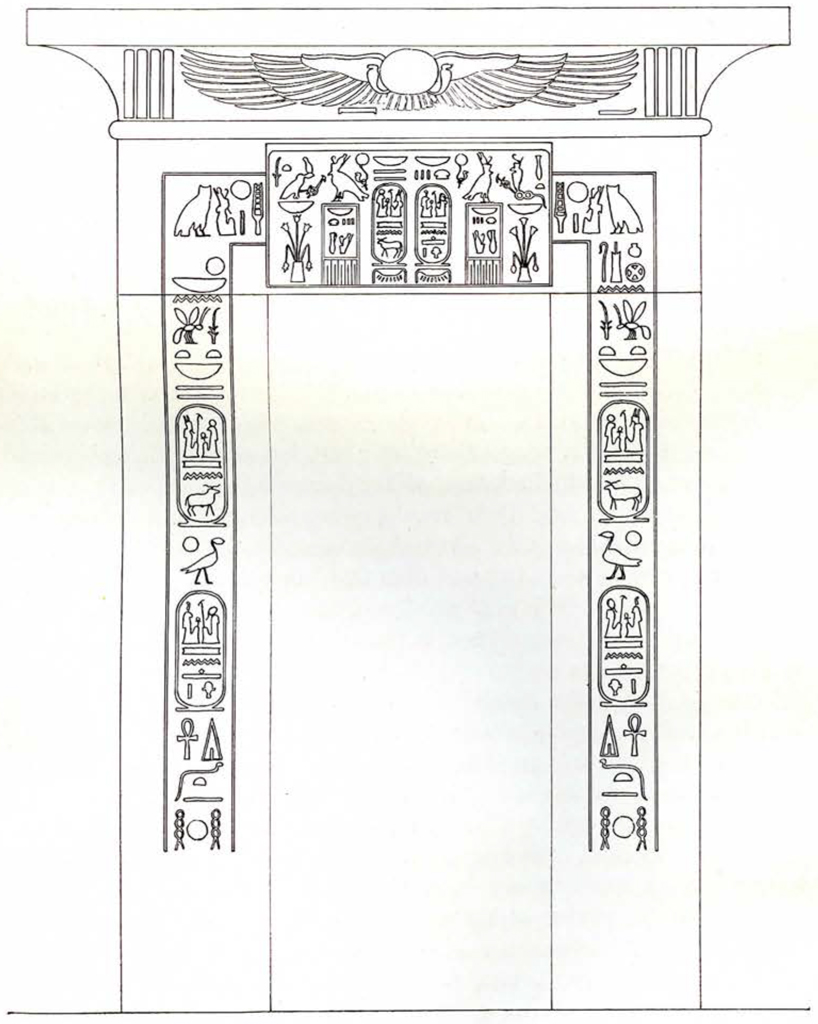

The entrance to the throne room from the vestibule was much wider than the doors leading into the side chambers but its height was not in corresponding proportion so that it had a somewhat squat appearance. A heavy lintel increased this effect. Each side of the door framing was a single upright block, containing double vertical lines of inscription giving the two names of the king with his titles of “Lord of the Two Lands,” “Lord of Diadems” and variations of the usual ending for long life and happiness. At the bottom was a small panel showing two gods of the Nile bringing in jars of the water which gives life to Egypt. The panel continued inside the opening with one figure and one vertical line of inscription above it. At the upper end appeared the Horus name of Mer-enptah, which differed somewhat on each lintel. The figures in the panels were in low relief but all hieroglyphs were inlaid with blue faience. They were first marked out on the surface and then chiselled away to a depth of about three eighths of an inch. The faience was apparently made in sheets which were cut up as required into pieces of the proper size and shape. Simple signs were formed of a single piece but more complicated ones and those having long curves had to be made up of separate bits fitted together. The edges were cut with a bevel and the pieces were bedded in white cement which was allowed to squeeze up between the joints as the faience was pressed into position and the excess wiped off the surface.

The lintel was made of two blocks, one forming the main architrave and the other the overhanging cornice above it. As these stones had to span not only the opening but the two sides of the door framing as well, they were over seventeen feet in length. The decoration was very elaborate and was a fine example of the ability of the Egyptian artist to lay out a design with due regard to symmetry and beauty. The composition filled the space and inscriptions were combined with the relief figures with considerable cleverness. In the centre at the top a winged sun disc held two chains of ankh and uas signs. This formed the axis of the composition and on either side were two scenes practically the same but reversed for the sake of symmetry. In the first was Merenptah seated on his throne beneath a canopy. In front of him was a sort of standard, that on the right of the lintel bearing a figure of the Set animal and that on the left a hawk headed animal, both wearing the dual crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt. Both held out towards the king the emblems of life, happiness and endurance. The standards had two human arms holding staffs of many years and the emblem for the anniversary festival. At the ends of the lintel were scenes where Merenptah stands before the shrouded figure of Ptah, the great deity of Memphis in a shrine. At the right end was Merenptah receiving from the god the emblems of life and happiness and at the left he gives to Ptah a small figure of Truth. On the cornice were a series of cartouches with the king’s names alternating with groups of three vertical feathers. At the ends of the cornice were two hawks with partly folded wings. All the human figures on the lintel were in relief, but the wigs and crowns were inlaid with faience specially made to fit. Portions of the robes were covered with gold foil. All hieroglyphs were of faience.

The actual doors were double and when open rested against the sides of the opening behind the stone framing. They turned in bronze sockets which were fitted into heavy stone blocks in the threshold. The wooden framing was four inches thick and the edges were strengthened with heavy wrought bronze, which appeared as straps across the door. On these were engraved the two car-touches of the king, and were probably gilded.

The six smaller doors inside the chamber were of the same technique, but on the lintels were inscriptions only and no relief scenes. The main panels were symmetrical designs of the two Horus names of the King combined with his two regular cartouches, while short inscriptions started from each side and continued down the framing. The wording on each door varied but followed the usual formulae. On the cornice was a winged sun disc, of which the feathers were inlaid with a number of pieces of blue faience outlined with gold leaf, while the disc itself was wholly gold.

The columns had an inlaid band of inscription similar to those on the door frames extending around the base. The bottoms of the shaft had lotus sepals in relief starting from a wide band of gold. Between the tops of the leaves were inlaid lotus flowers. Half way up were scenes in relief corresponding to those on the main lintel or substituting for the scenes of offering to Ptah, a picture of Meren-ptah slaying his foes before the shrine of the deity. The capitals were decorated with an elaborate pattern of cartouches between lotus stalks and flowers.