The wonderful discoveries made at Ur and Tell el Obeid by the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and the University Museum were briefly reviewed in the March JOURNAL. The very early forms of Art, going back to the Fifth Millennium B.C., recovered at Tell el Obeid in the neighbourhood of Ur, give a striking and vivid picture of Sumerian civilization at a very early stage, but still far from its beginning. For illustrations of the Dairy Scene and some other art objects the reader is referred to the March JOURNAL.

The temple of the goddess Nin-har-sag, the Lady of the Mounts, discovered in the neighbourhood of Ur at Tell El Obeid, by the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and the University Museum, was founded about B.C. 4300 by King A-an-ni-pad-da of Ur. His father was Mes-an-ni-pad-da the first king of the first Ur Dynasty as recorded on the precious chronological lists of Nippur preserved in the University Museum. Tell El Obeid is a low pile of ruins, 4½ miles distant from the stage tower of the Moon God Temple at Ur. The name of King Mes-an-ni-pad-da on the tablet in the University Museum had been deciphered some ten years ago, but his existence, as well as that of the two previous dynasties of Kish and Erech back to the flood, seemed somewhat legendary and mythical until the present sensational discovery, to use the words of C. L. Woolley, the Director of the Joint Expedition. From his monthly reports we borrow most of our information, to let the readers of the JOURNAL realize the importance of the find while awaiting the complete scientific publication.

Three buildings have been discovered by the Joint Expedition at Tell El Obeid at different levels, the deepest and original building being that of A-an-ni-pad-da, the uppermost being erected by King Dungi of the Third Ur Dynasty, while the middle one is attributed to the kings of the Second Ur Dynasrt some time between 4000 and 3000 B.C.

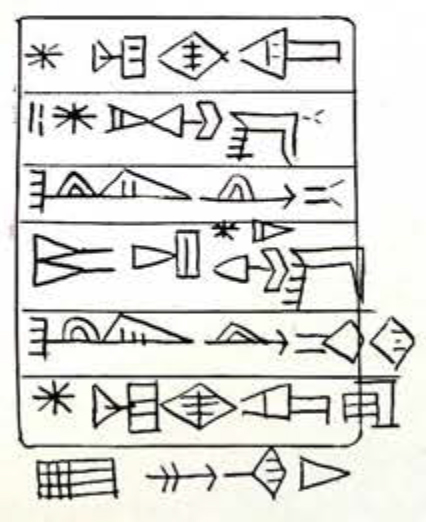

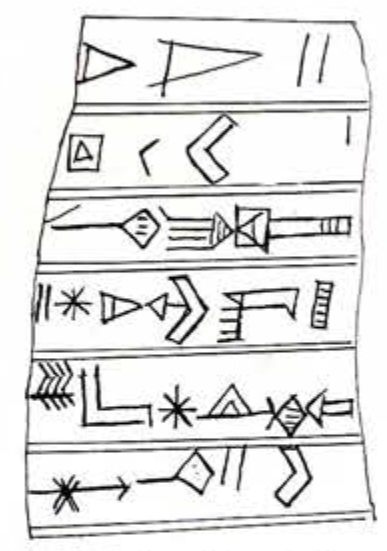

The first building, that of A-an-ni-pad-da, is dated by documents inscribed in the cuneiform characters and discovered in the ground. They are: a soapstone foundation tablet, a gold scaraboid bead and a fragment of a stone vase with a votive inscription. The foundation tablet, No. 1, read as follows.

“To Nin-har-sag, A-an-ni-pad-da, king of Ur, son of Mes-an-ni-pad-da, king of Ur, for Nin-har-sag, he has built a temple.”

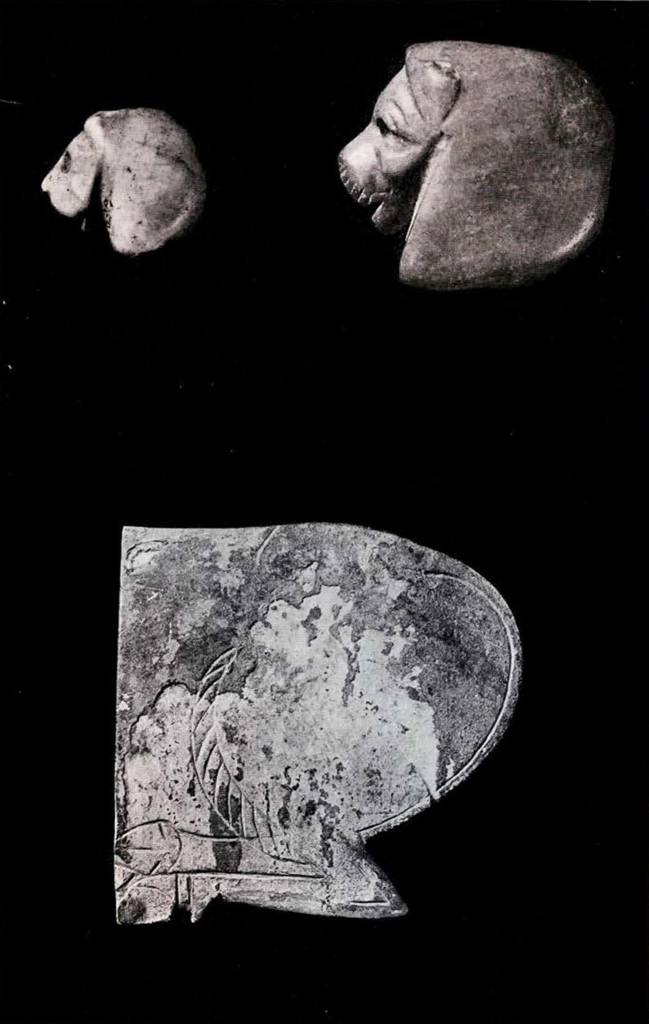

The gold scaraboid, No. 2, pierced in the length, has engraved on the convex, back “A-an-ni-pad-da, king of Ur.” It is a bead, and probably a seal. The oldest seals, before the invention of the cylinder seals in connection with clay tablets, were first flat seals or beads carried as pendants in a necklace. The convex back might be carved in the likeness of an animal figure, lion’s head, vulture, eagle, crouching bull or scarab. It was an emblem, a personal mark. The flat side resting on the breast might have some mysterious emblem, such as an animal figure cut so as to transform the object into a seal used to impress the personal mark. But that personal mark, to which later on was added a name written in cuneiform characters on cylinder seals, has to be traced back through the flat seal to the bead and the personal ornament which gives it its full cultural value. We know several seals of the Cassite Period, B.C 1600 to 1100, deposited in temples as votive offerings: “shakin aban duppi shuatu.” The gold svaraboid bead or seal of A-an-ni-pad-da may be such a votive offering.

The votive inscription on a fragment of stone vase, No. 3, records the dedication to A-an-ni-pad-da of a stone vase decorated with metal to carry some liquid such as water or milk (?). The dedication was by Nannar-ka, and the ceremony included a libation.

The building of A-an-ni-pad-da may be the oldest known Sumerian Temple. Only the famous constructions of king Ur-Nina and his predecessors at Tello Lagash—can compare with it. They have much in common. ” It is a rectangle—with an angle due North—with a projecting platform containing a staircase on its S.W. side and another projection approached by a massive staircase on its S.E. side. It consists of a platform with a containing —buttressed—wall of burnt plano-convex bricks above which rose a building of mud bricks of plano-convex form and red colour. The projections were also in mud bricks.”

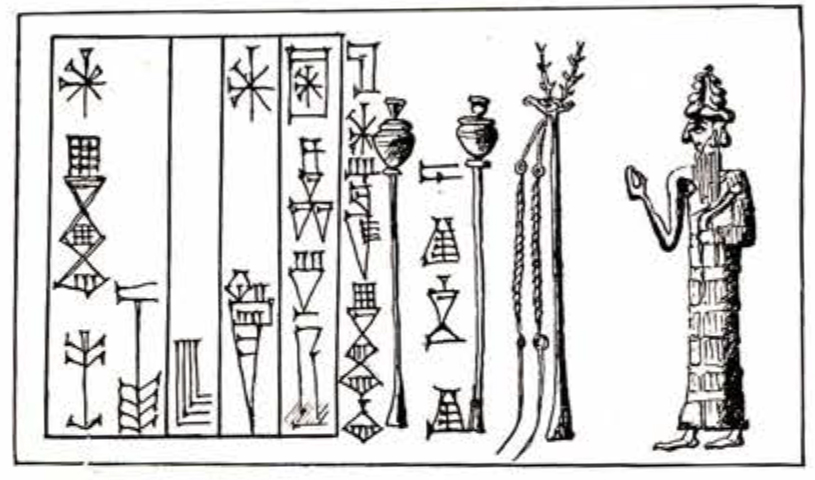

The old Sumerian temple was first a terraced enclosure with ramps or staircases leading to the upper level. This is the temenos or sacred area with the four angles at the four points of the compass. Within the paved court—kisallu–like the Latin templum or the modem khan, was erected one or several shrines and later the famous stage towers. But the towers are just an exaggerated development of the terrace, and the receding stages a necessary condition of the massive mud construction. The sacred enclosure and the threshold, whatever may be the god or the symbol within, are the oldest and most important features. They are a development of pens and parks with their entrance reinforced by posts with a side buckle, probably to fix a crossbar, as we shall see when studying the stone and copper relief ornamentation of Tell El Obeid. The same buckled posts alone or in the hands of the mythical keepers of the gates, Gilgamesh and Enkidu, are the symbols of shrines seen on either side of enthroned gods like Siru the serpent god, Enki the god of waters, and Babbar the rising Sun god. The archaic representation of a bull crouched in front of a winged gate is likely connected with the Moon god of Ur, or Nin-har-sag of Tell El Obeid. Later the buckled posts were confused with lances, especially in the case of the war god, or were replaced by colossal clubs.

At Tello the entrance was marked by huge brick pillars. From the beginning the sacred threshold and its pillars are a symbol of temple and shrine. They have a close relationship to the square and round fenced enclosures on the archaic Elamite reliefs, into which the primitive hunters forced wild animals to be captured. And the buttressed platform with ramp is not far from the wooden scaffold on which the old Elamites built their round mud granaries with an opening above to which a ladder gave access.

The sacred area at Tell El Obeid was enlarged probably by the kings of the Second Ur Dynasty. A new wall enclosed the whole of the hilltop where stood the original building of A-an-ni-pad-da. The hill was terraced with mud bricks of a square form and of a grey colour under which the old temple was buried 5 feet deep. In the retaining wall were used burnt bricks of the square model and marked with a finger print.

The scanty remains of the upper and last building have been identified with King Dungi of the Third Ur Dynasty, about B.C. 2250. In connection with this last builder it is interesting to recall that the Museum possesses, since 1888, a soapstone foundation tablet of his father Ur-Engur—CBS. 841—which may have been discovered at Tell El Obeid in the past and which records the reconstruction of the temple of Nin-har-sag. In that case Tell El Obeid would be the old Sumerian city of Kesh, a fact of some consequence. The tablet reads as follows.

“To Nin-har-sag, his Lady, has Ur-Engur, king of Ur, king of Sumer and Akkad, built Kesh, her favorite temple.”

The temple of Kesh has a place apart in Sumerian literature. It is the temple of Nin-har-sag, a goddess of mountains, probably of Elamite origin, a great goddess—Nin-Mah—like Ninlil, another mountain goddess, the mother of all fecundity under the name of Nin-tud, to whom bulls and cattle were especially dedicated in the dairy at Tell El Obeid. Her shrine is a symbol of white purity. But her connection with Elam, from which country were probably imported the first tamed bulls and cows, is most illuminating. We read that Rim-Sin the Elamite king, who about B.C. 1970 extended his power over the royal cities of Erech and Larsa, was proclaimed legitimate ruler of Sumer in the temple of Kesh.

A tablet from Nippur1 is interesting in connection with the ornamentation of the Tell El Obeid old building, because it has a description of the temple of Kesh as known to the scribes of the Isin Dynasty about B.C. 2000. It forms a striking commentary on the design and decoration of the newly discovered building together with its mythological symbolism.

Hammurabi is the last king on record who showed interest in the temple of Kesh, about B.C. 1928. In the prologue of his code are mentioned his restoration of the enclosure and provisions for a rich food endowment.

A series of remarkable objects of art which decorated the walls and entrance of the old building of A-an-ni-pad-da, were recovered by the Expedition where they had fallen. They were embedded in the clay and covered with the layers of the new terrace, erected 6000 years ago. They consist of copper statues of bulls and lions in the round; copper reliefs of crouching bulls forming a frieze; stone or shell bas reliefs of all kinds of animals, bulls, bisons, eagles, ducks, ibexes, in cut pieces, fixed with copper wire on a wooden panel and inlaid in bitumen within a copper frame; there are also limestone plaques carved in low relief and incised fragments of shell. In the same connection were found sundry pieces like the gold scaraboid bead, stone vases inscribed or decorated with relief, mosaic columns and mosaic flowers, beams of palmwood covered with copper plates- in short a treasure house preserving for our enjoyment an amazing collection of early Sumerian art.

The smiths of Tell El obeid were experts at casting metal. In their statues, the head is generally cast apart, and attached to the body of the animal formed of thin beaten copper plates nailed on a wooden core. The horns of the bulls were in some cases of gold, cast apart and attached by rivets. The eyes-of shell and bitumen- were inlaid. The bulls are over 2 feet high.

The copper basreliefs shown on page 7 of the March JOURNAL, form a variant of the same collection. The body of the bull is a beaten plate of copper nailed on the board. The head cast in the round is attached to the neck and stands boldly out facing the observer. The bull is represented crouched, one knee up, as ready to rise in a very effective and natural attitude.

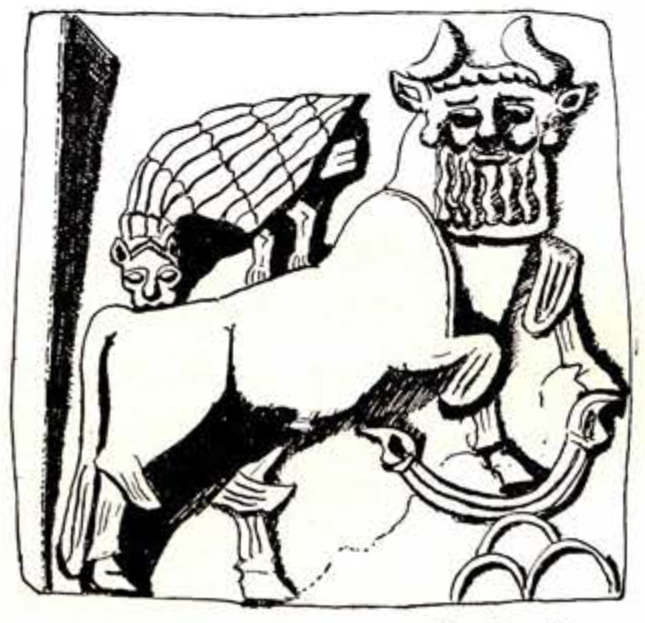

One stone basrelief, No. 4, is carved out of one whole block or plaque. It represents a human headed bison in full run among the hills. A lion headed eagle has fastened its claw on the animal’s hind quarters. The group is known from other Sumerian monuments. It forms a realistic coat of arms and its symbolism is not doubtful. The bison with long flowing beard, crescent horns, tufts of hair- a sign of strength- growing at the joints is an inhabitant of the Elamite hills. The water buffalo with the rugged slanting horns is not represented before the time of Sargon of Agade, B.C. 2700. The lion headed eagle dominates the tame animals and seizes them in its talons. He is an emblem of the corral or park, the doors of which beat and open like wings.

The eagle is the animal sacred to Ningirsu the warrior of Enlil, god of thunder and lightning who inhabits the summit of the mountains, as the eagle is sacred to Jove in the Greek mythology. Very archaic cylinder seals represent antelopes, goats and ibexes, crouching in a park by a reed or wood construction or gate, and dominated by an eagle with spread wings which has seized them in its talons.

The basreliefs of cut pieces of shell and limestone inlaid in bitumen belong to a special technic of mosaic and inlay decoration to which may be traced later even Damaskeend steel. The black bitumen is both cement and effective background for the white stone design and genre composition. The inlay material included all kinds of precious metal and coloured shells and stones; alabaster, limestone, lapis lazuli, and mother of pearl being commonly used. Horns, ears, eyes, eyeballs, beard, locks of hair, checkered spots on the robe, or fancy decorations, were attached or inlaid in that way, as were also mitres, turbans and parts of dresses.

A long line of passing bulls2 is the simplest form of relief, and a picture familiar and endearing to pastoral peoples. The abundance of cattle was a sign of prosperity. Ducks, geese, goats and ibexes belong to the same simple pastoral life, No. 6.

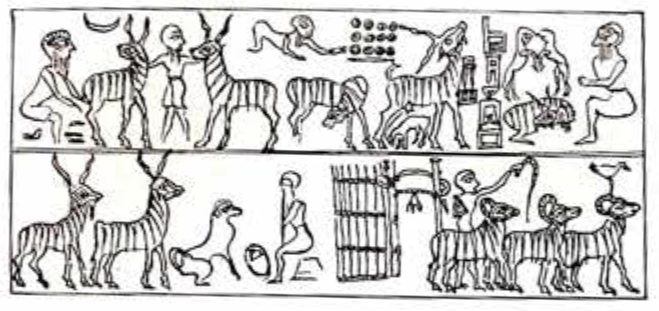

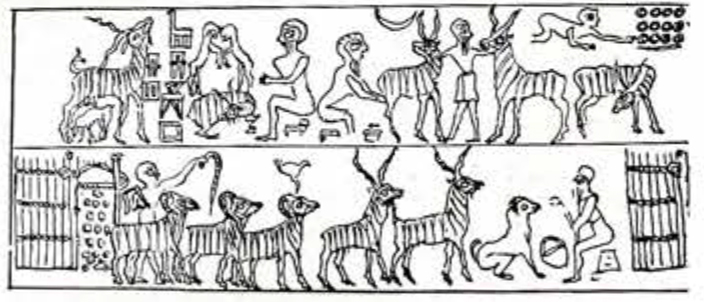

The finest basrelief is a charming pastoral scene which restores under our eyes a part of the active life at the dairy of Tell El Obeid.3 On either side of a central reed byre typical Sumerians are milking their cows and storing the precious liquid. The gate is the central motive of the panel. The reed construction is easily understood. The most remarkable features of the gate are the two buckled posts on either side of the entrance and the crescent decorating the upper part over the lintel. Two heifers are coming out of the byre which might as well be a shrine. The Moon god is called the young Bull of Heaven and the resemblance between the crescent, his emblem to the end of the Babylonian times, and the horns of the bull is obvious. The Bull of Heaven, a round relief on a shallow bowl of steatite from Ur, dating about B.C. 2300, has a white shell crescent inlaid between the horns.4 A gate with crescents over the lintel is part of the geometrical designs decorating a still earlier steatite vase from Tello, No. 7. The checker lines, and herringbone constructions on either side are an imitation of wicker work. We learn from Strabo that the famous χαλαμὣνες of the marshes of Babylonia were plaited and bedaubed with bitumen to make waterproof vessels. But the interesting connection between pens and shrines, gates and buckled door posts will be better illustrated by a comparison with a few archaic pastoral scenes from Ur, Susa, Tello, Nippur, engraved pm stone reliefs, plaques and seals, and scatted in various publications and museum. They derive a new light from the basreliefs of Tell El Obeid.

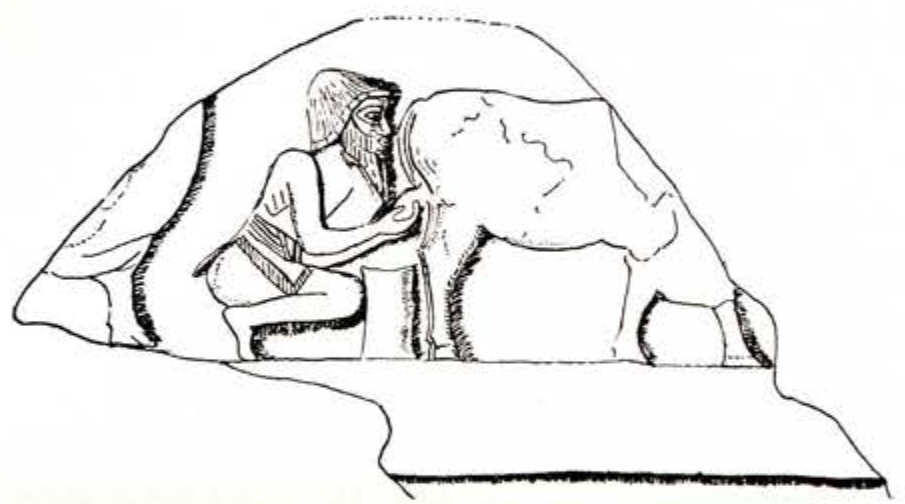

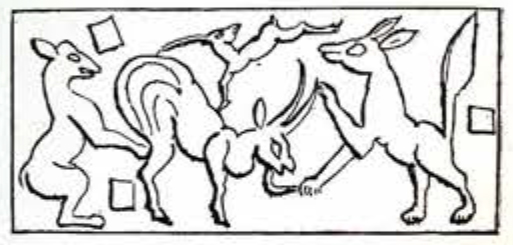

Turn to an examination of the new Dairy Scene.5 The milking scene on the right is remarkable. The position of the milking man behind and not at the side of the animal is quite unexpected. The calf is muzzled and attached by a rope to the neck of its mother, to prevent it from being suckled, and also to keep the animal quiet during the milking process. The milker is squatting, not resting apparently on any stool, and holding at the same time between his knees the pointed jar in which he collects the milk. The milkers of today, while not always using stools, are usually squatted or seated by the side of the animal when milking cows, but sheep and goats are commonly milked from behind. The almost invisible udder bespeaks an early age of farming, when long breeding had not yet developed the hanging teats which we associate in our minds with the image of the cow. The limestone basrelief of Ur, No. 8, interpreted first as the castration of a bull, is in reality a milking scene. The position of the milking man is identical. The milk pail with a flat bottom, the same that we shall find in many milking scenes, and in the hands or on the head of many worshipers, is resting on the ground. The same interpretation must apply to an Elamite seal impression, No. 9, with a scene of a goat arrested by two animals, fox, wolf or dog, and erroneously considered as humorous. It is in reality a milking scene. One of the animals holds the she goat by the beard and horns while the second is playing the milker. The flat bottomed pail is not missing, and the other square objects in the field may be more milk pails. The most interesting point is that we are transported to the animal world, characteristic of Elamite mythology in Sumerian texts of B.C. 2400. The Elamite mysterious fox or wolf is elsewhere represented as paddling a boat in the middle of the marshes, and a wild bison as throwing the arrows of lightning like another thunder god.

Returning to the Dairy Scene from Tell El Obeid, the scene on the left shows the storage of the milk. The well balanced composition has a central active group between two secondary figures. Two are masters seated on cubic stools- or thrones gish-gu-za- with four legs and no backs, and two are servants standing and working. The milk is poured from the pointed jar through a funnel or strainer of very modern aspect, into a flat bottomed vessel resting on the ground. This latter vessel, which has perhaps three or four small legs, tapers toward a narrow mouth. Milk, butter, cheese, and many kinds of beverages besides beer, wine and oil of different brands and qualities are mentioned in the earliest inventory lists. The long pointed jar used for milking, and the flat bottomed vessel differ clearly from the two big jars to the right and left of the central group. On one side a servant prepares one of those big jars. His hand and arm are thrust through the mouth of the vase as if busy cleaning it. The jar stands on its point. In the second case the jar has been filled and sealed and the second seated figure holds it, not on the point but lying on its side, while a rope fixed round the bulky vessel helps to handle it. Big jars with handles—perhaps rope handles—and also reclined on their sides, are represented on some rare Elamite seal impressions.

From a later period, that of Gudea, patesi of Lagash, about B.C. 2400, we borrow an interesting text describing the organization of the household of the patron god Ningirsu.

“In order to multiply the butter and the beverage—beer or buttermilk(?)—so that the serpent in the house of E-ninnu, the temple of Ningirsu, do not get away with the cream of the sacred goat, the goat which suckles the kid Lulimu, the mother of Ningirsu, he let En-lulimu, the shepherd of the Lulimu kid, take his place near Ningirsu under his order.”

This is only one instance of a dairy attached to a temple. The role played by the animals, the serpent which steals the cream of the goat which is the mother of the god, has a strange flavour of the old Elamite mythology. Nin-har-sag the goddess of Tell El Obeid was also a mother of gods and kings whom she nourished with her sacred milk. Another mother—we should say cow—goddess who played the same part at Lagash under the name of Gatumdug, presided over a regular farm including the following features.

“teams of bulls and their drivers, cows and calves and their cowboys, sheep and lambs, goats and kids and their shepherds, she asses and fillies and their drivers.” Small and big cattle are always carefully distinguished and their keepers called by different names. The sign for cowboy is a picture of a cow pen, the sign of the shepherd is the stick, the whip, the pastoral scepter. Naturally the cow farmer is sedentary, while the owner of sheep and goats that feed on poor grass and clover in travelling large tracts of land, is a nomad. The cow farmer of Tell El Obeid is a shaven and shorn Sumerian, while the sheep and goat shepherds usually wear the short hair and beard of the Elamite or of the nomadic Semite.

At the time of the third Ur Dynasty, Drehem in the outskirts of Nippur, was a big farm, just like the farm of Gatumdug at Lagash, or the farm of Ninharsag at Tell El Obeid.

Besides her temple at Tell El-Obeid or Kesh, Ninharsag had temples in Girsu and in Umma, cities which are among the oldest Sumerian settlements. At Nippur she was identified with Ninlil. She was invoked in Elam by the patesi of Susa, Basha-Shushinak. She is one of the oldest Sumerian deities and her connection with Elam is significant. On the famous Stele of the Vultures and other early texts from Tello she has charge of pens and byres, the pure enclosures. The name of her place, Kesh, means also: protection of the divine enclosure. Another name of her shrine is the Solid Reed Construction, the Brilliant Grove. The shrine proper, built in the middle of a terrace, was graced with her statue seated on her magnificent throne of Majesty. Stone and metal vases were used for the ritual functions of her cult. Two doves placed in front of a slender vase with palm branches and bunches of dates were an acceptable offering. In the shrine within the limits of the temenos, she would deliver her oracles. She had a rich treasure house with silver and precious stones that tempted many a plunderer.

As a goat was the mother of the god Ningirsu, so perhaps was Ninharsag or Ninlil, the mother of the Moon god of Ur, a divine cow. The cultural and religious aspects of the Sumerian art point toward an early connection with Elam. Both obey the same inspiration and follow the same rules, which we may briefly sum again: a predominance of animal figures and natural scenery; few or no anthropomorphic representations of the gods; an untiring repetition of the same figure forming a frieze or procession; opposition of figures upside down or heraldic grouping on dither side of a central motive; a combination of face and profile instead of true perspective.

But the Elamite is a passionate hunter of the wild animals of the hill land: goat, sheep, ibex, antelope, deer, gazelle, urochs, bison, boar and lion. The Sumerian of Tell El Obeid is the peaceful farmer concerned with his tame cattle. Their physical appearance is different. The Sumerian is shaven and shorn and wears only a sheepskin or woollen kilt. The Elamite has beard and hair, turban, cap and tunic. The most interesting contrast is found in the different representations of the gods. To Elamite imagination are due the composite monsters: bullman, lionman, birdman, scorpion-man, serpentman. The same forms have been adopted by the Sumerians, the best known being Enkidu, the bullman, companion of Gilgamesh. Also the dragons and griffins, animal composite monsters, are common to Sumer and Elam. But while the Elamite deifies the animal and gives him a human attitude as throwing arrows, paddling a boat, milking a goat, in Sumer the god very soon divests himself of his animal form to assume the appearance of a king seated on a throne. The ancestor animal survives as his servant and emblem. Gilgamesh, the hunter, and the bullman Enkidu are the keepers of the gate of the park transformed into a shrine, and they hold the buckled posts. The serpent god with a human bust on a serpent coil is a witness of this gradual transformation. He was originally worshiped at Der on the border between Elam and Sumer. To the farmer industry of the Sumerian, the farming of animals and the tilling of the land, are due the beginnings of the great Babylonian civilisation. Sacred temenos and walled cities go back to fenced pens and parks.

In connection with the Sumerian art of Tell El Obeid a few known monuments are here reproduced anew with a short description.

No. 10.-Sumerian shepherds and their dog (?). They are perhaps worshippers in a procession. They carry a stick and a palm (?). The pointed jar with a spout is of a very archaic type, a symbol of liquid offering. They are shaven and shorn. One figure seems to wear a turban. Their only garment is the sheepskin or woollen kilt. Long straight nose and small chin are truly Sumerian. Tell El Obeid relief on a fragment of large limestone vase or basin, the bur-mah of the texts.

No. 11.- Fragment of a dairy scene (?). A seated figure and a reed construction. Two pointed jars suggest milk and cream. Impression on a clay sealing from Nippur.

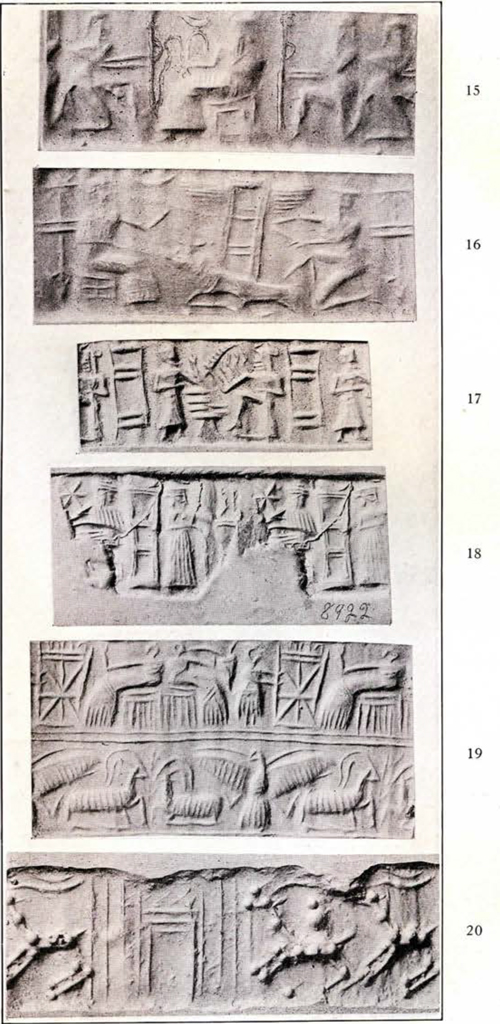

No. 12.- Two primitive Sumerian gods partaking of some ceremonial feast. The gate with the buckled posts is the symbol of the shrine. Archaic cylinder seal reproduced from W. H. Ward.

No. 13.- The hero Gilgamesh holding the two buckled posts. He is the traditional keeper of the shrine’s gate. He is a famous hunter like Nimrod, a king of Erech of the many enclosures, and a builder of its great wall according to a tablet in the Museum collections. He is here represented in front face with long hair and beard and naked as engraved on a mother of pearl plaque from Tello.

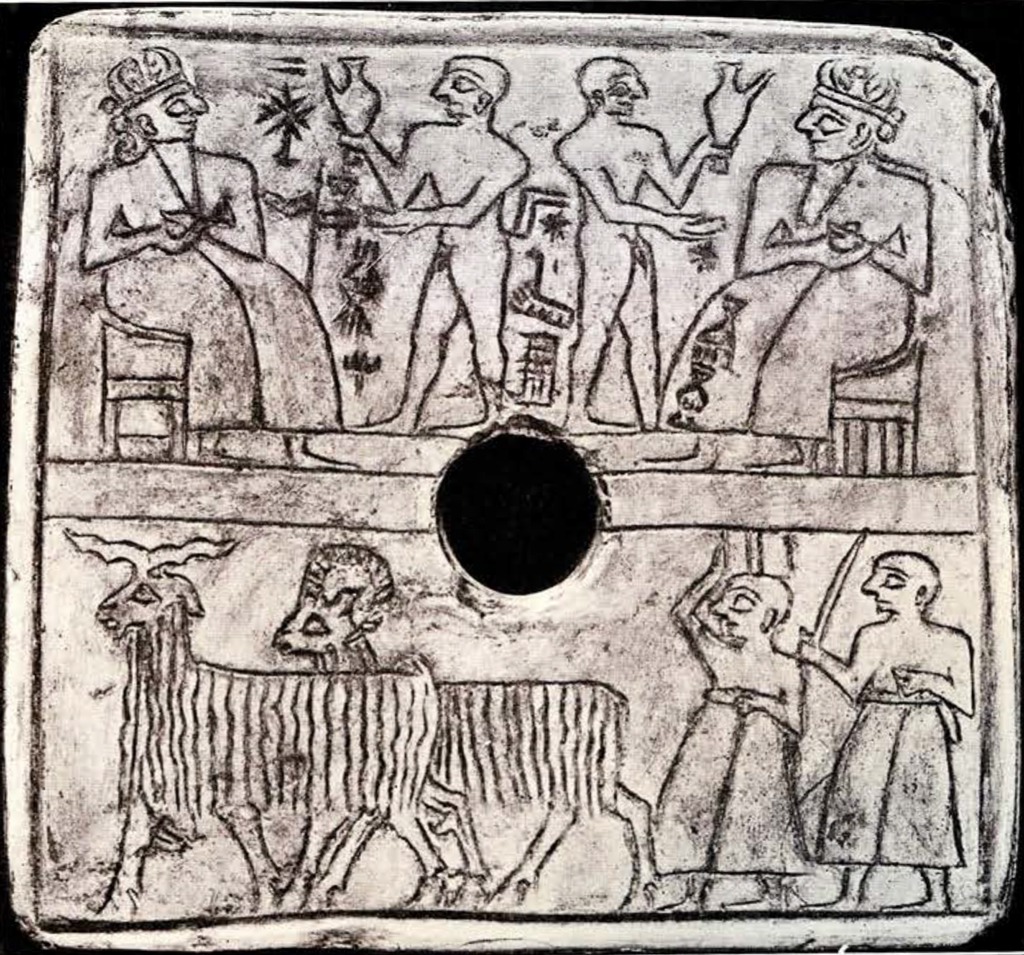

No. 14.- The god of water in his shrine and a kneeling Gilgamesh keeper of the buckled post of the gate. Seal cylinder of the Brussels Museum published by L. Spleers.

No. 15.- The god of water Ea holding the spouting vase and a kneeling Gilgamesh holding the buckled post of the shrine. Seal cylinder in the Museum Collections, CBS. 5058.

No. 16.- A goddess seated, perhaps Ninharsag, holding the extremity of a rope which is attached to a winged gate. A kneeling Gilgamesh holds the other end of the rope, and makes sure the closing of the gate. A crouching bull completes the picture of a pen like the byre of Tell EL Obeid. Crescent and sun star mark the evening and morning. Seal cylinder in the Museum Collections, CBS. 5003.

The seal of Basha-Enzu, the first king of the IVth Kish Dynasty, about B.C. 2992, who carries the title of never failing husbandman of Ur, has also the symbol of the passing bull, an emblem of the Moon god, the young bull of heaven. Seal cylinder in the Museum Collections. CBS. 5005. Cf. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1922, pp. 60-65.

No. 17.—The Sun god Babbar with flaming wings and notched sword rises in the morning over the mountains of the East. In front of him there is a worshiper and a pile of cakes on an offering table. A gate is a symbol of the shrine. Seal cylinder in the Museum Collections. CBS. 3790.

No. 18.—The serpent god on a rare shell cylinder unfortunately broken. The human bust rests on a coil partly visible. In front of him a worshiper pours a libation. Three branches arise from a huge vase or hourglass shaped altar between. A gate is the symbol of the shrine. Star and crescent mark the evening and morning. Seal cylinder in the Museum Collections. CBS. 8922.

No. 19.—Two archaic Sumerian gods seated on ancient thrones drink through a pipe out of a pointed jar. A priest or door keeper holds one post of the gate. Their style makes them contemporaries of the Tell El Obeid reliefs. The lower register with the spread eagle seizing in its talons two crouched goats is the vivid symbol of the penfold. Seal cylinder in the Museum Collections. CBS. 5008.

No. 20.—Two antelopes and a reed construction symbol of the park. Seal cylinder in the Museum Collections. CBS. 14395.

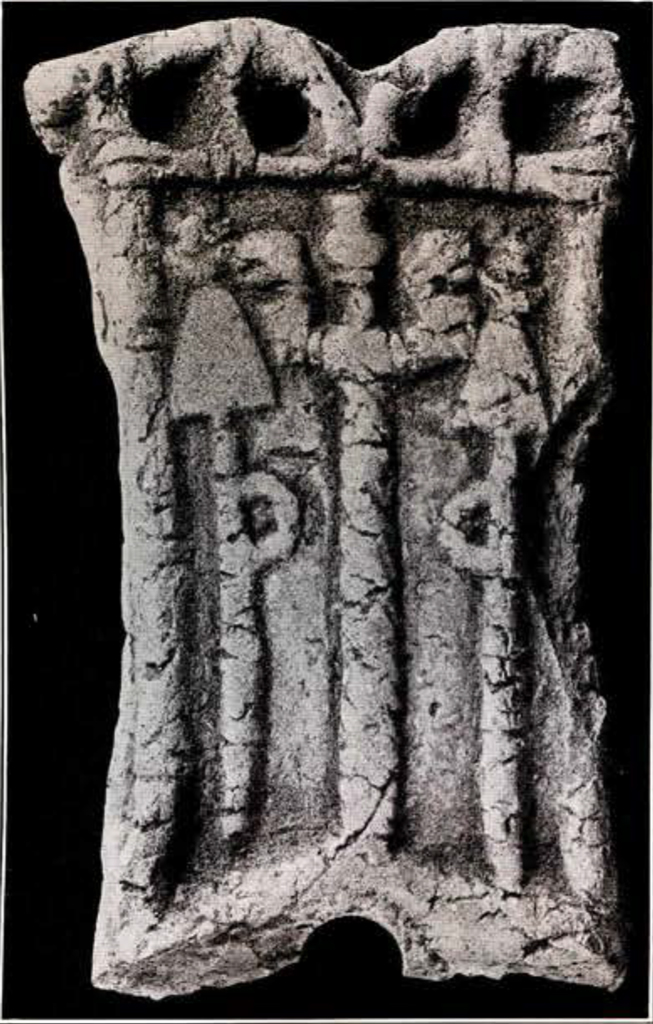

No. 21.—Clay relief, front part of a chariot protecting the driver from the dust and horse’s kick. The relief represents the emblem of the war god Ninil, a club between two lions’ heads, standing between two buckled lances, a symbol of the shrine very appropriate on a war chariot. Nippur collection in the Museum. CBS. 15397. A more complete relief in the Yale Babylonian Collection shows the same buckled lances derived from the buckled posts in the hands of two Gilgameshes on either side of a gate surmounted by a crouching bull. Moon and star and passing birds complete the symbolism of the shrine.

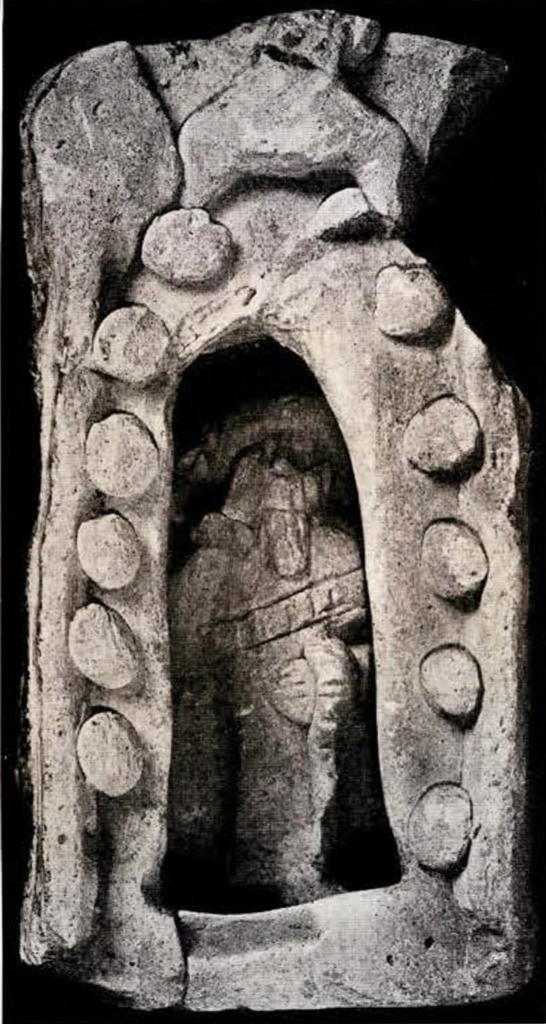

No. 22.—A terracotta shrine with a little statue of a god from Nippur. The bearded god with a turban, one hand covered by the folds of his shawl, the other raised to his mouth, is in no way characteristic and probably belongs to a late period, but the two lances on either side of the entrance and the symbol above are in keeping with the oldest tradition. The twelve lumps of clay suggest a boss knob or rosette decoration. CBS. 15396.

No. 24.—Flat seal of red marble with the convex back representing a lion’s head. The eyes were inlaid. The flat side has 3 lions engraved in the hollow. Museum Collections. CBS. 14537.

No. 25.—Same type in white marble. CBS. 14538.

En-he-gur, shepherd

dEdin-mugi, minister of the divine she asses of reproduction(?).

Ur dLugal-edin-na, the medicine man is thy servant.

There are pastors of asses called sib anshu-ama-gàn sib ama-gàn-ša. Perhaps instead of anshu, ass, it would be better to translate lulimu, doe, which would agree with the decoration of the whip, and answer to the divine shepherd En-lulim of the Gudea text.

In brief the Tell El Obeid reliefs and other works of art seem to bridge over the gap between the Pre-Sargonic and the Pre-Elamite Periods. Remains of the same type have indeed been discovered by the French at Susa, Tape-Mussian and Bandar-Buchir. The Pre-Elamite Period represented by the painted vases and engraved seals seems to be the oldest of all. But the Tell El Obeid period, while not so primitive, is through its naturalistic scenery and absence of human figuration of the gods, to be set apart and before the Pre-Sargonic Period. The new period of art may be called by the name of Tell El Obeid or of the First Ur Dynasty.

1 CBS. 14229.↪

2 CBS. 14229.See THE MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1924, p. 26.↪

3 See THE MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1924, p. 26.See THE MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1924, pp. 10, 11.↪

4 See THE MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1924, p. 26.↪

5 Ibid, pp. 10, 11.↪