Four centuries ago to this very year, in 1526, a handful of men stood on the deck of a tiny caravel off the coast of southern Colombia. For more than a year they had endured the arduous privations that were the lot of the sixteenth century explorer: hunger and thirst, the enervating climate and the irritating attacks of insects. Before them waited unknown dangers, starvation that had already claimed a large portion of their number, hostile natives and all the terrors of the imagination. Behind them lay relative peace and security. And yet the unknown lands ahead beckoned to the stout hearted with hints of adventure, discovery and wealth. Fourteen of the company elected to remain with Pizarro and carry on the conquest of Peru. Seldom has history recorded an instance of such steadfast adherence to purpose in the face of stupendous odds.

But such has ever been the lure of Peru. Though today no Inca army bars the way, yet many diseases, among them malaria, typhoid and dysentery, still lurk in wait for the unimmunized stranger from the north, and not infrequently they take a dear toll from him whose audacity and determination lead him to ignore or underrate them. Such was the fate of Dr. William Curtis Farabee, late Curator of the American Section of the University Museum1. Drawn to Peru by the wealth of its archaeological material and while in active prosecution of his work, he was stricken down with fever and dysentery, from the results of which he never recovered. Possibly he might have entirely recovered his health had not his devotion to his duty and to science induced him to recommence and continue work in Peru and Chile possibly too soon. Taken ill in June, 1922, he refused to abandon his undertaking, but remained in western South America until February, 1923, alternating periods of work with periods of rest and convalescence. Returning to Philadelphia, in April, 1923 he endured more than two years of slowly sinking illness until his death in June, 1925. The present article, offering a brief account of his last expedition, is prepared mainly from his field notes, diaries and letters and illustrated by his photographs.

Peru is a land of peculiar interest and fascination to the archaeologist. Here are found the remains of wonderful old civilizations which had long been forgotten and buried under the desert sands when Pizarro first set foot on the land. In some respects the Peruvian cultures may claim to have been the most highly advanced of any in America. Though absolutely without any system of writing—in which respect they fall far behind the Mexicans—they had developed a wonderful social system based on a decidedly socialistic plan. Though far inferior to the Mayas of Yucatan in the beauty of their architecture, yet their stone walls are extraordinary examples of the mason’s art, and the great megalithic works such as the stupendous fortress of Sacsahuaman may be numbered among the most impressive works of man.

Especially is Peru notable, however, for the perfection of the finer and smaller products of handicraft. No other region in America bears so close a resemblance to Egypt in this respect. The coast of Peru is a very narrow strip of land, the snow covered Andes being in many places visible from the sea. These rob the prevailing winds from the east of their last drops of moisture, so that decades may intervene between rain storms on the Pacific Coast. This region is therefore a perfectly desolate sandy waste except for the narrow valleys of the frequent short rivers which descend from the snowy crests of the Andes, valleys which blossom and yield luxuriantly as the tropical sun beats upon the well irrigated fields. And in these pleasant fertile valleys, as in Egypt where almost similar conditions prevail, civilizations developed very early, and many industries were brought to an extremely high stage of development. Here also, as in Egypt, the dead were buried in cemeteries in the dry sands of the desert where they were preserved from the decay wrought elsewhere by the damp. Doubtless this form of burial was chosen by these ancient peoples with this very object of preservation in view. For, although the names of these peoples, and all the facts of their history are utterly unknown to the archaeologist, yet from the contents of their cemeteries he can draw a better picture of their life and culture than he can of many another American people much better known to history. Thus, not only are the dessicated mummies excellently preserved, with their buried possessions of fine textiles, baskets, objects of wood and shell, and feather mosaics, but even the vegetal products buried with the dead for sustenance on his journey to the other world are easily identifiable today. It may well be that the Mayas and Aztecs of Mexico did as wonderful work in perishable materials as did the Peruvians, but their more humid climate did not permit the preservation of any cloths or other objects made of organic materials, and the high quality of these is known only from the glowing reports of the earliest travellers and conquerors.

At about the time of the opening of the Christian era, three important civilizations had evolved in Peru; one in the highlands which centered at the great site of Tiahuanaco near Lake Titicaca in Bolivia, and two on the western coast, one in the north near Trujillo, and one in the south near Ica and Nazca. Those on the coast, probably the oldest, were later decidedly affected and influenced by Tiahuanaco. In much later days, not long before the Spanish Conquest, the engulfing tide of the Inca armies from the highlands overwhelmed the coastal civilizations and imposed pure Inca culture upon them.

This is the story illustrated in the cemeteries of the arid coast which reveal in their contents changes and developments such as those recorded. In the oldest graves, objects of local origin alone are found; later, Tiahuanaco types appear, and, finally, objects of the peculiar highland Inca type.

Image Number: 25168

The Nazca civilization was the latest archaeological discovery in Peru. It was first found in 1901, and yet only twenty years later when Dr. Farabee was in Peru for the celebration of the centennial he could write that the whole Nazca country had been rifled and its wonderful treasures scattered throughout the world by mercenary men. By the time that Dr. Farabee arrived in the Nazca valley prepared to investigate its ancient culture, that valley had all been turned over in promiscuous fashion to supply the demand for the beautiful Nazca pottery. That Dr. Farabee was able to excavate an excellent collection under these conditions is indeed remarkable.

It was doubtless while observing large collections of Nazca pottery at the Peruvian Centennial, to which Dr. Farabee went as special representative of the United States Government in 1921, that he formed the idea of excavating at Nazca, for the University Museum had, until that time, not a piece of this beautiful ware. This, then, became the primary object of his latest expedition to South America on which he started early in 1922.

Leaving New York, February 5th, he and Mrs. Farabee arrived in Lima, the capital of Peru, February 20th. Upwards of a month was spent in the neighborhood of Lima while Dr. Farabee obtained the sanction of the Peruvian Government for his expedition. During this time Dr. Farabee utilized his leisure in excavating at Chorillos near Lima, and in studying collections in the museums. Finally, on March 25th, together with Gaston Tweddle, a seventeen year-old Peruvian boy, Dr. Farabee left Callao by a Chilean steamer, and arrived at the port of Pisco, a city of only four thousand inhabitants, some 150 miles south of Callao, the following afternoon.

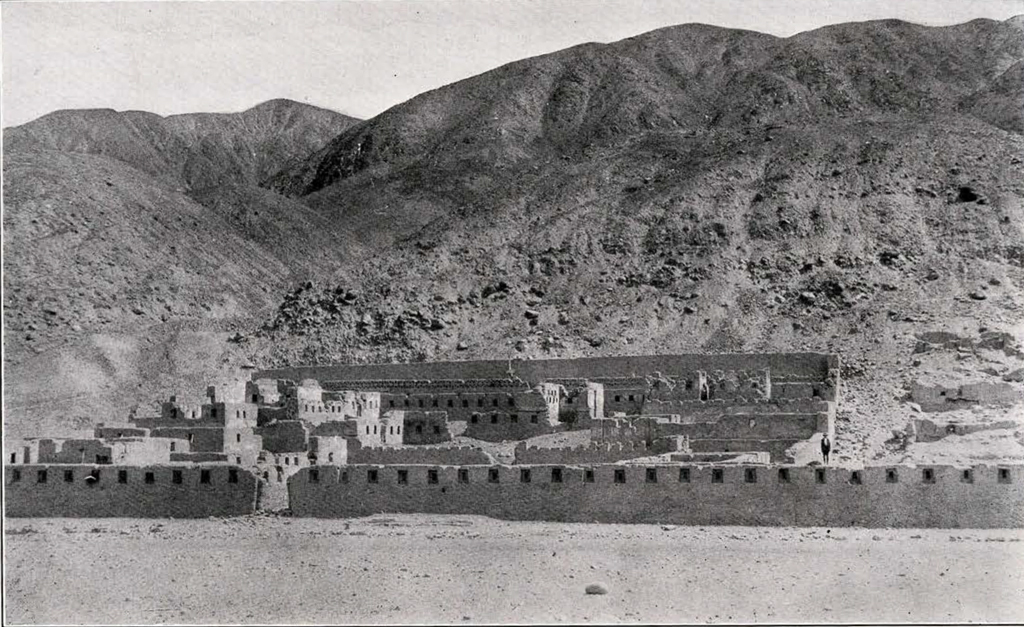

On March 28th he went up the Pisco River some thirty miles to the hacienda or plantation of Monte Sierpe, where he remained until the 31st. During these few days Dr. Farabee made a careful examination of the famous Tambo Colorado which lies five miles further up the valley at an elevation of twelve hundred feet. Tambo Colorado, or Pueblo Colorado, is the best preserved ruin in all Peru, as Dr. Farabee’s photographs well indicate. Of pure Inca architecture, it was built in the later days of the Inca Empire, probably about the year 1500. Though the roofs are fallen, the walls with their typical niches remain, built of stone below and adobe above. The red, yellow and white coloring which was applied to the walls may today, after a lapse of more than four centuries, still be seen at a distance of a quarter mile, Dr. Farabee reports in his notes. On both sides of the river below Tambo Colorado are many other ruins in a poorer state of preservation, the mountain sides are terraced to a considerable height, and old irrigation ditches are everywhere visible, indicating a large population. He made very detailed notes, drawings of the plan and details of construction and photographs of this impressive structure.

Image Number: 25165

The week from April 1st to 7th Dr. Farabee spent in the nearby Ica valley, where he studied some important private collections and investigated the numerous ruins in the valley. He reports that they were very poorly built of sandy adobe brick, now crumbling to dust.

The next few days took him to the neighboring Nazca Valley, his principal goal. Leaving Mamacona in the Ica Valley on April 7th by automobile, a few hours’ run down the valley brought him to the hacienda of Ocucaje. Thirty miles more across the high pampa and the hacienda of Huayuri was reached. For a mile and a half the road led across soft sand. Two lines of posts had been fixed in the ground and between these brush had been piled to a thickness of two feet, a very expensive undertaking. The narrow valley Dr. Farabee reports to be full of ruins, those in the valley being built of adobe, those in the mountains of stone. A run of another hour brought him to Cabildo, where, apparently, the night of April 7th was passed.

The height of the Rio Grande at that time kept the party at Cabildo all of April 8th and the morning of April 9th, and Dr. Farabee as usual utilized this time in investigating the archeology, the records of which are among his notes and photographs.

At last on April 9th the party forded the Rio Grande and reached its goal at Nazca. After a day or two of investigation and preparation, Dr. Farabee commenced his excavations, which continued in Nazca Valley from April 13th until May 20th. For thirty miles he followed the Nazca River, excavating in every site which offered any promise of result.

Image Number: 25132

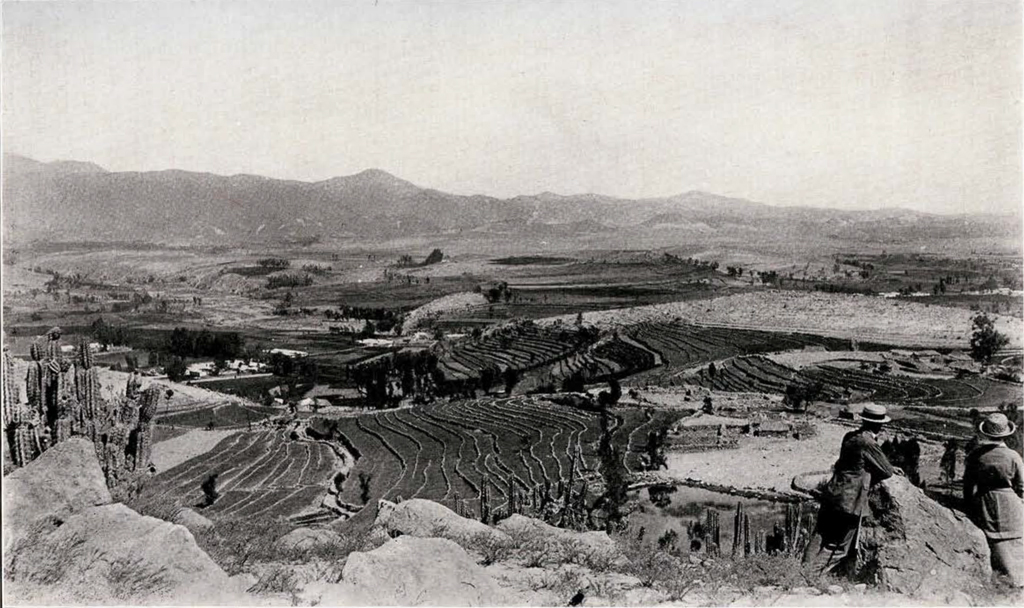

Of the valley Dr. Farabee reports, “There must have been a very great population here in ancient times in comparison with the population at present, two thousand or twenty five hundred. The land under cultivation was about the same or somewhat greater in ancient times. Many of the irrigation ditches are the same. The other day the river was in flood on account of rains in the mountains. Crossing the valley, I found one ditch of clear water, while all the others were muddy. After following it up, I found the origin of the ditch in a continuation under the river. Another day, looking for a drink, I found another clear stream; following up, I found an artificial cut some thirty feet deep leading from the valley a quarter of a mile into the mountains. The water is always clear and never goes dry, although the river is dry for eight months. These ditches are the work of the ancients.”

During his six weeks of work in Nazca Valley many beautiful objects, mainly of pottery and textiles, were secured.

Dr. Farabee kept accurate notes of his excavations and the contents of each grave, but these details are of interest only to the professional archaeologist.

Image Number: 25133

The body or mummy was generally found on the floor at the base of the tomb, wrapped in cloths and surrounded by pottery vessels which probably originally contained food and drink for the sustenance of the deceased on his journey to the other world. These mortuary offerings ran quite a gamut as regards quality and quantity, being probably an index of the wealth and social standing of the deceased. Some bodies were without any accompanying objects, others possessed nothing but a few ears of corn, some a rude pot or two, while one boasted of as many as nine exquisite pottery vessels and other mortuary objects of value.

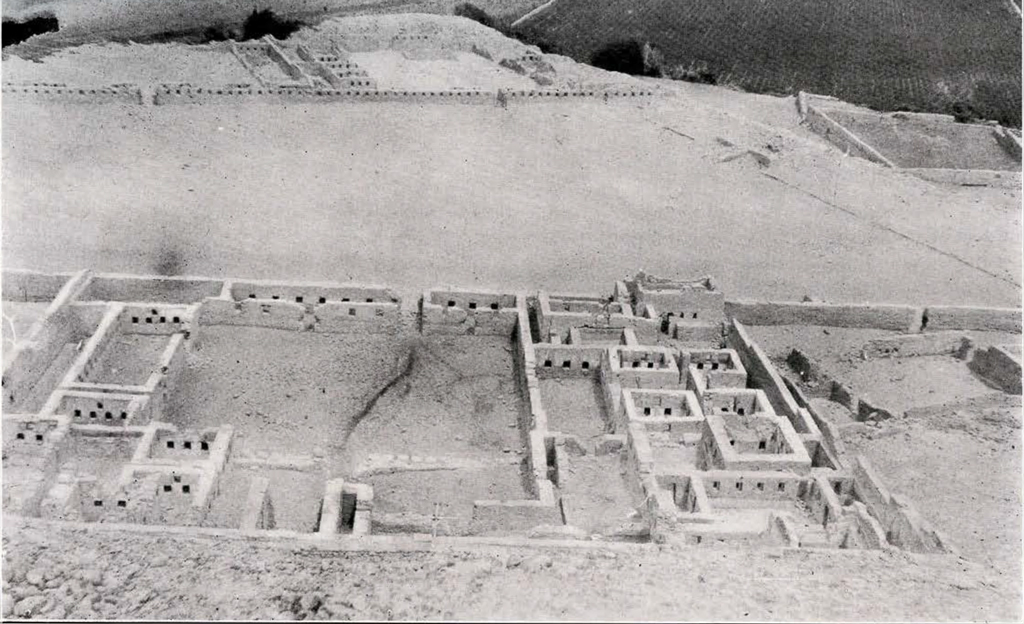

The ruins at Nazca are not extensive or of great interest, far less so than the cemeteries. The architecture of the Pacific Coast, being mainly of adobe brick, has suffered fax more from the ravages of time, and consequently is far less impressive than the wonderful stonemasonry of the highlands. Dr. Farabee notes that the ruins at Nazca are found on the south side of the river, opposite the present village. They occur from the bottom of the valley to the level of the height of the citadel, 110 feet, the surrounding hillsides being terraced for house sites, not, as is more usual, for cultivation.

The main ruin at Nazca measures a thousand feet on the east and west axis and 350 feet on the north and south axis. The walls, which have been largely destroyed by earthquakes, are of adobe faced with large stones as much as ten inches in diameter and plastered over. During the earthquakes, most of these large stones have been shaken out, leaving in the walls only the small stones used to chink the interstices. The largest room measures forty feet in length, the floor having been made by levelling sand over the rock surface and covering it with adobe mud.

Image Number: 25113

The principal feature of the ruins at Nazca is known as the citadel, a name which is probably appropriate, inasmuch as it appears to have been a fort. It is practically in the center of the group of ruins and occupies a rocky promontory extending out from the foothill behind. It consists of two parts, stories or tiers, the upper one being circular except at the back, thirty six feet in diameter. The walls are of adobe brick, six feet high and plastered on the interior, with niches or embrasures on the parapet. The lower section is more irregular, with an apron extending fifty feet beyond the wall of the upper section. The floors of both are of the natural bedrock without adobe. The citadel is approached by a graded way and ascended by a staircase. That this site was in later years used by the Inca conquerors is shown by the fact that a wall of dressed stone blocks, in the technique typical of the Incas, in one place encloses the stairway on both sides.

Ceasing his work at Nazca proper on April 30th, Dr. Farabee moved his scene of operations to Cantayo, a short distance up the river, where he worked until May 6th. Then he moved to Esta-querilla, the hacienda of Manuel Carrera, governor of Nazca, at a distance of seven leagues below Nazca, where he conducted investigations and excavations from May 8th to May 20th. Estaquerilla2 is so named from a group of 240 forked posts of approximately equal height fixed in lines in the sand and presenting a strange and exotic effect in the sandy desert. The presumption is, of course, that they were employed to support the rafters and beams of an immense shed, the roof of which has long since disappeared, but it may well have served another purpose; all is conjecture.

These posts stand six feet apart in twelve rows of twenty posts each. They measure six or seven feet in height and apparently average six or eight inches in diameter. But in the center of the southern line are three massive posts the largest of which has a diameter of about two and a half feet. In addition to this main group, other posts standing singly or in groups of two or three, or lines of from five to twelve are noted all about Estaquerilla1. Other lines of stumps of posts indicate that there was a stockade of about a hundred yards square about Estaquerilla. But here there is little evidence of architectural features, only a very few walls of stone or adobe being found.

Considerable excavation was done by Dr. Farabee during his stay of nearly two weeks, although the local cemeteries had been almost entirely despoiled.

Image Number: 25210

At Cahuacha as well as at Estaquerilla, Dr. Farabee noted the presence of ruins; in fact, it is probable that ruins can be found almost everywhere along this coast. Those at Cahuacha, however, are not of the type to attract the attention of casual visitors. In many places the tops of the hills have been levelled, built up with adobe and made into terraces so that they stand up above the line of the hill. In other places, small mounds built of adobe bricks of a wedge shape are seen. Lines of adobe walls run for hundreds of yards, but most of these are now crumbled and disintegrated, reaching a height of two feet in only one place.

The shape of the adobe bricks employed differed greatly from place to place. At Nazca, apparently, square bricks made in moulds were typical; at Estaquerilla square bricks were entirely missing, the adobes being of a wedge shape and hand made, built into the wall in the same way as stones at Nazca. The wedge shaped adobes were found also at Cahuacha, but in the upper part of the valley above Cahuacha they were cylindrical, ten inches long and six to eight inches in diameter, also hand made.

At two other places in Nazca Valley Dr. Farabee made investigations: at Tambo de Perro, four miles below Estaquerilla and at Las Cañas, six miles above Estaquerilla where he notes that the adobes were hand made cylinders.

The last dated entry in Dr. Farabee’s Nazca notebook is that of May 20th at Estaquerilla. However, there are several pages following, referring to Cahuacha, Tambo de Perro and Las Cañas, and his expense sheet refers to work in Nazca Valley until May 26th. From this time on, and except for detailed and dated notes of his work later at Arequipa, Pisco and with the Araucanian Indians, the details of Dr. Farabee’s life must be gathered from occasional letters written by him and Mrs. Farabee. Apparently, during most of this time, he was too ill, weak and indisposed to keep a diary.

It was evidently in the Nazca valley on or about May 26th that Dr. Farabee first contracted the illness which, after a lapse of more than three years, was to claim his life, a martyr to the cause of scientific research. The complaint was inflammatory dysentery, one of the diseases most prevalent and feared in the tropics, caused, generally, by the infected drinking water which one must endure in isolated arid places. The place where he was taken ill was at a distance of 154 miles from Ica, the sole source of medical attention, a city of some ten thousand inhabitants. Though ill, apparently he rode fifty two miles on horseback the following day, May 27th, from Nazca to Cabildo. Such a trip across desert trails is an arduous task for one in the best of health, and for Dr. Farabee in his feverish condition, it must have been torture. Small wonder he collapsed in a native hut at the end of the day. From here he sent for an automobile, for which he waited three long painful days. Dr. Farabee’s perseverance in his work needs no fuller encomium than is found in the mute evidence of the following item in his expense account : “June 1—Labor—Cabildo.” Evidently during these three feverish days, he had kept his men at work excavating. That very day he endured an even more exhausting ride of more than a hundred miles in a small automobile over the rough trails of the Pampa Huayuri to Ica. Naturally he barely survived the journey, and the terrible hardships acting upon his constitution, which, although originally robust, had doubtless been weakened by the malaria from which he had suffered on his previous trips to Guiana and the Amazon, undoubtedly laid the foundation for the pernicious anemia which, baffling the best help which medical science could offer, eventually overcame his heroic resistance. As it was, he could not have lived two days longer without medical attention. Too ill to be taken to the best hospital at Lima, he was removed to the estate or hacienda of a local friend. A slip of paper found in one of his notebooks, apparently a nurse’s record of his treatment for June 4th and 5th written in Spanish, gives a sufficient insight into the gravity of his illness, an average of above one administration for each of the twenty four hours being indicated. But he rallied under the tender ministrations of Mrs. Farabee, who joined him about that time as rapidly as poor transportation facilities permitted, and apparently was convalescent by the middle of the month. However, he was not able to travel until June 23rd and then went by way of Pisco, Callao and Lima to Chosica, a health resort at a moderate altitude in the mountains twenty miles beyond Lima, where they arrived on June 25th. He had then lost forty pounds in weight and could with difficulty walk a hundred yards.

Image Number: 25203

Fifteen days of rest at Chosica not proving a high road to convalescence, Dr. Farabee went to the British-American Hospital in Callao for the week of July 12-18. From here he decided to carry out his long projected trip to Arequipa, a health resort of much higher altitude in southern Peru. They left on the 18th and reached Mollendo, the seaport, July 20th, Dr. Farabee “well, but thin and weak,” as he optimistically reports.

In the beautiful healthful region of Arequipa Dr. and Mrs. Farabee remained from July 20th until August 24th, recuperating under the shadow of the majestic snowcapped volcano “El Misti,” 19,200 feet high. Even in his weakened condition, his mind was constantly on his work and the objects of his expedition. In a letter of August 23rd he states that although thin and light he felt in good health and had been exploring the region for three weeks. The whole valley, he reports, was formerly occupied, and the terraces are used for house sites today. Regarding his excavations, I quote his report almost verbatim.

“Eight miles east of Arequipa is Sabandia, a summer resort; it was also the center of ancient culture. The hills all about are terraced to their tops with little houses dotted between. Burials were made on the tops of surrounding desert hills. . . .”

In two weeks of digging, Dr. Farabee secured over one hundred pottery vessels. On account of the greater humidity of the climate, however, all perishable objects such as he found so perfectly preserved at Nazca had entirely disappeared.

Image Number: 25215

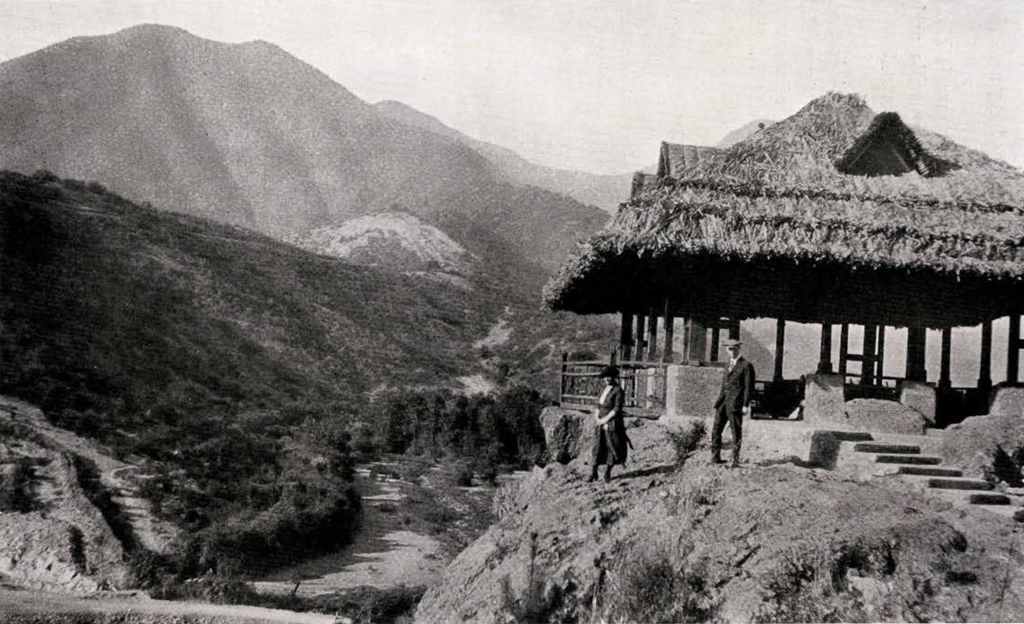

Another place investigated by Dr. Farabee was at the mountain pass of Corralones on the trail from Arequipa to the sea, about seventy miles from the sea and thirty from Arequipa. It appears to be near the station Quishuarani on the railroad from Mollendo to Arequipa. This is about one third way on the old Inca road from the capital city of Cuzco to the sea and, as the river here bends so as to come within three miles of the trail, it was probably an important point in early days. The pass is two thousand feet above the river and seven thousand above the sea. Here in aboriginal days was one of the inns or tambos which the Inca rulers maintained on their road at intervals of a day’s travel, a building of dressed stone of two rooms and a “corral” or wall of stone, all now in ruins.

The interesting feature of this place, however, is not the tambo but the petroglyphs. Dr. Farabee reports that the whole mountain is covered with granitic boulders of all sizes, weathered to a reddish brown color on which figures were made by pecking with another rock through the weathered patina to a depth of a quarter inch. The making of these figures had evidently continued from the earliest times up to the present. Figures of men on horseback and initials with dates contrast with figures of entirely aboriginal content. Dr. Farabee records that one date, 1652, seemed fresh in comparison with some of the obviously earliest markings. ” The feathered two headed serpents appeared the oldest, along with geometrical designs, suns, deer and faces. There were no dogs and few llamas, but many deer, frogs, foxes and lizards.” The photographs which he made of these petroglyphs afford a far more realistic impression of them than can any description.

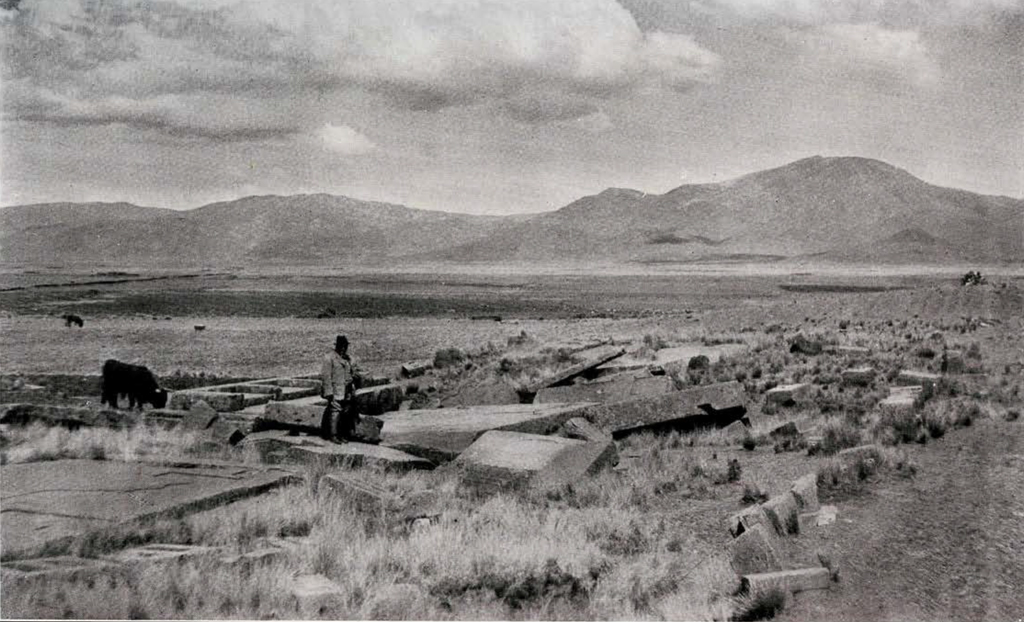

Image Number: 25285

On August 25th, Dr. Farabee felt sufficiently recuperated to attempt a longer trip and, taking advantage of the hospitality of Mr. T. A. Corry, accompanied him in his private car to La Paz, the capital of Bolivia. La Paz is a most picturesque city of 107,000 inhabitants, situated at an altitude of 12,120 feet in the southern Andes. A considerable part of the population is composed of Aymara Indians, and thousands of other Indians of the same group crowd the city on market and fiesta days. A few miles away on the shores of Lake Titicaca are the extraordinary ruins of Tiahuanaco, the center of the early and semimythical ” Megalithic Empire” which probably flourished in the early years of the Christian Era and disseminated the influence of its culture far and wide throughout western South America.

Returning to Arequipa for a few days on August 29th, Dr. Farabee proceeded again to the highlands on September 15th, this time to the romantic city of Cuzco, apparently with the purpose of making researches and excavations in this region. He remained in Cuzco until September 30th, much of the time living with Dr. A. A. Giesecke, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, Rector of the University of Cuzco and sometime Mayor of the city. But Dr. Farabee found himself too ill and weak to attempt any arduous labor at this altitude of 11,380 feet and had to content himself with observing the better known features of this old capital city of the Inca Empire, the city which was as sacred to the ancient Peruvians as is Mecca to Mussulmans. Here on November 15, 1533, Francisco Pizarro completed the conquest of Peru.

Cuzco today retains little of her former glory and plays but a small role in the interests of modern Peru. Compared with the 223,000 inhabitants of Lima, the modern capital, Cuzco’s 30,000 people, many of them Quichua Indians, count for little. But this very fact of unprogressiveness has permitted the historical background to persist largely unchanged and the city to remain a Mecca for tourists, archaeologists and historians. Here as nowhere else in America can the old be glimpsed in the present. The old pre-Columbian Inca masonry still shelters in its shade Indians of pure Inca blood whose costumes and customs have been changed but slightly and superficially since the days of Pizarro and Atahuallpa.

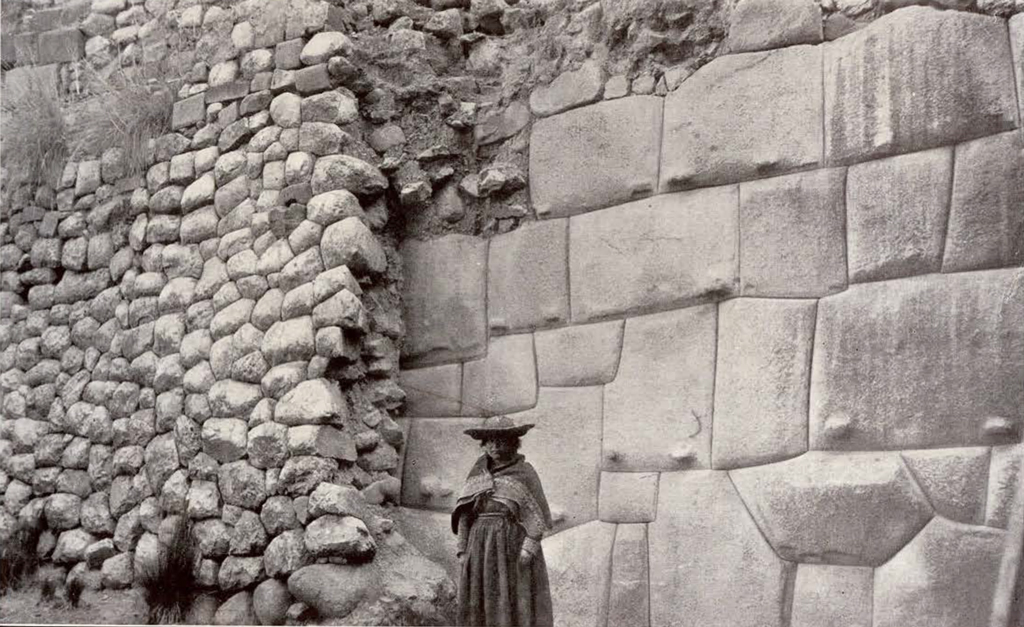

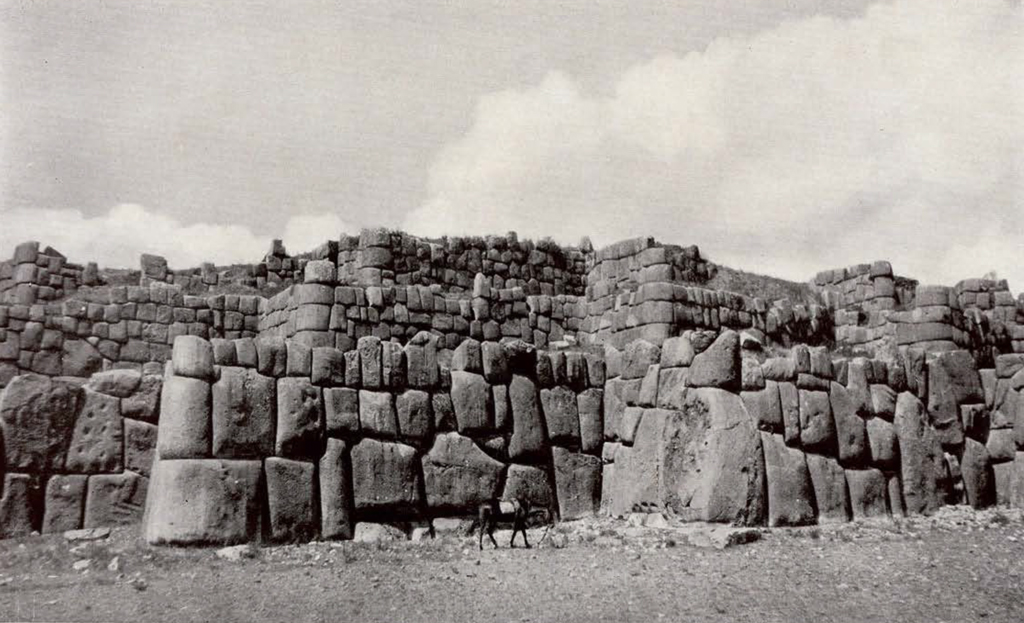

Image Number: 25191

Aboriginal Peruvian masonry is interesting, admirable and in places stupendous. The walls stand today as firmly as the year they were erected, although no mortar or other cementing material was used in their construction. So nicely are the stones fitted together that the adjacent surfaces are broad, even, flat and smooth, meeting so closely that a knife blade cannot be inserted between them, and standing firmly. The stone blocks were not cut to uniform or even approximately uniform size, but were apparently selected at random, of various sizes and shapes, and their sides abraded down to fit their neighbors and the exact space to be filled. The labor required to dress such stone blocks with the use of only stone tools and sand abrasives—for iron and steel were totally unknown and bronze implements not suited to the work—can hardly be imagined. Apparently the masonry of the earliest days was the most careful and marvellous, the workmanship deteriorating, as is often the case, in later days. It was this architecture which has given the name Megalithic Empire to that old culture which preceded the Inca and whose principal seat was probably at Tiahuanaco. The most impressive example of this work is found at the awesome fortress of Sacsahuaman which guards the northern approach to Cuzco, on the brow of the hill 760 feet high, overtowering the city. The total length of the walls is about eighteen hundred feet, but the central portion consists of three parallel walls twelve hundred feet long, with zigzag reentering angles built according to the modern type of fort engineering. The lower wall measures twenty seven feet in height, the middle wall eighteen and the upper wall fourteen feet, a total height of fifty nine feet. But the astounding feature of Sacsahuaman is not so much its majestic proportions as the massiveness of the individual blocks composing it. These are of an almost incredible size, the blocks at the salient angles being especially enormous.

Some of the earlier chroniclers speak of the blocks as having been brought from quarries five to fifteen leagues away. Even discounting this latter statement, it is difficult to understand how a people, ignorant of modern engineering theory and possessing only the rudest appliances without metal parts, could ever have transported and erected such immense blocks, even granted unlimited reserve of man power. The cyclopean blocks are generally not erected in regular courses, but each block is dressed so as to join closely with its neighbor.

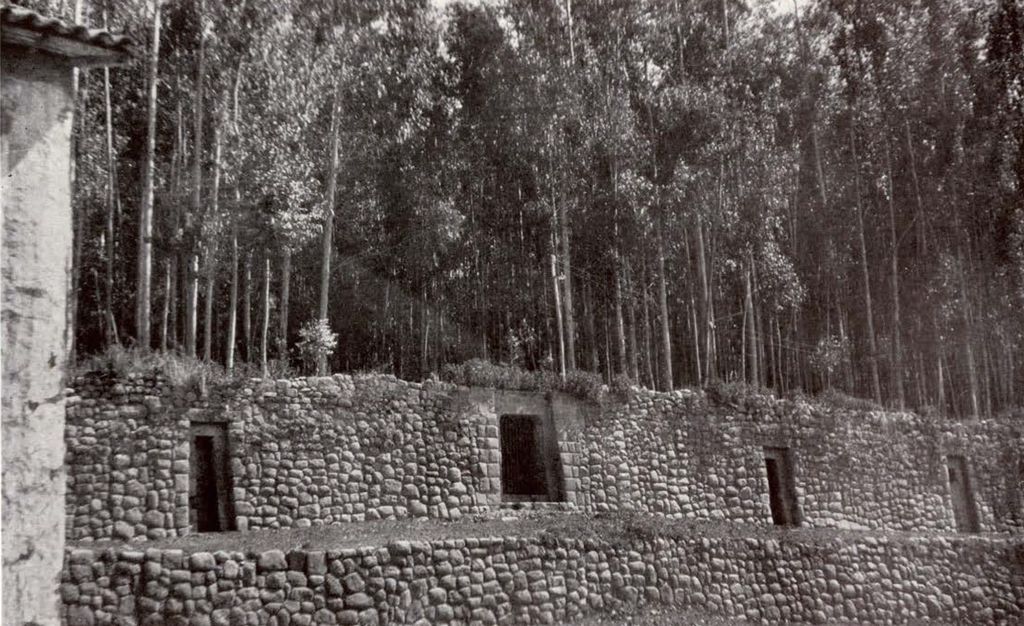

This same style of masonry is seen in the walls of many old buildings in Cuzco today, one famous large stone block being known as the “Stone of Twelve Angles,” so many modifications of its faces having been required to cause it to fit the faces of its neighboring stones. A second type of masonry is apparently later and somewhat inferior, the stones smaller, less angular and less carefully dressed. Of such masonry is built the Colcompata, another majestic structure on the outskirts of Cuzco at the base of the Sacsahuaman hill. This is believed to be the wall of a palace built by the first Inca, Manco Capac. The doors and niches so typical of Inca architecture, converging towards the top, are well illustrated in this structure.

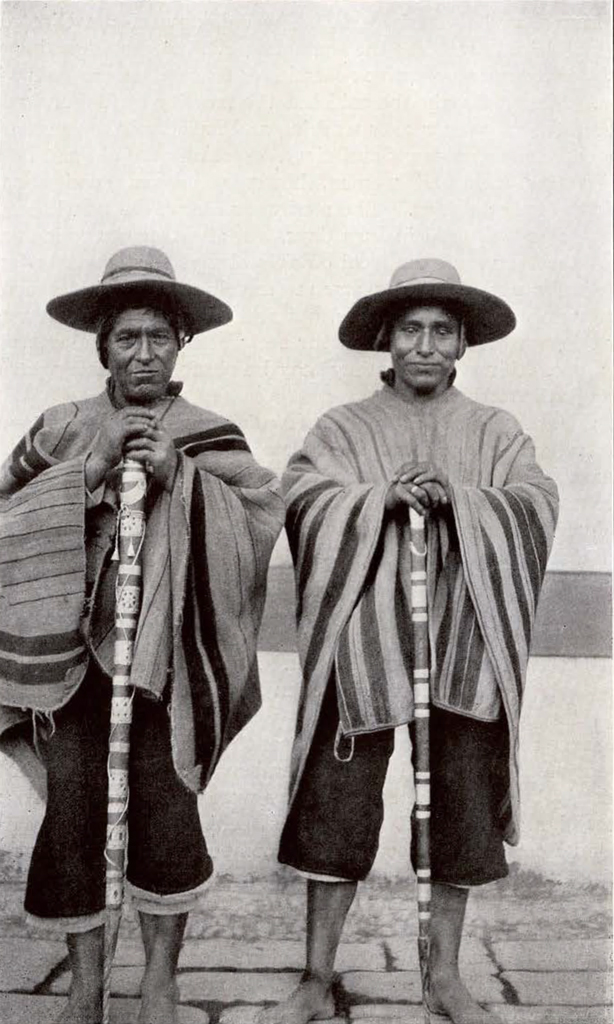

The Indians of the highlands of Peru and Bolivia, the Quichua and Aymara, dress in very distinctive costumes, the result of a blend of aboriginal and Spanish garb. The chilliness of the climate at this high altitude requires that sufficient clothing be worn, but the poverty of the average native necessitates that it be worn to the last thread. Since not only the cold but the scarcity of fuel and water in these bleak regions makes washing and bathing infrequent, most of the natives are unkempt and dirty, especially the old and infirm. The younger men and women, however, possess good apparel, especially for fiesta days. The men wear the woven poncho of the same type as that used in Inca days, but also trousers which reach only to the knee, and the local officials always carry as a badge of office elaborate staffs. The women wear voluminous skirts, generally a large number of them at once, but still affect the shawl, worn, as in Inca days, with the corners at the neck fastened with a large silver pin or topo. Always busy, they may be observed spinning yarn as they walk the streets.

Dr. Farabee remained only a few days in the neighborhood of Cuzco, returning to Arequipa on October 1st. Here also his stay was short, for, impatient of more delay and anxious to prosecute his researches further, he planned to return to Pisco, where he had seen some interesting ruins. Leaving on October 18th, he spent several days looking over the field, and on October 24th inaugurated excavations at Puntillo, near Pisco. Here he remained at work until November 18th, excavating at Puntillo, at Manrique Solar and surrounding places and making side trips to Pisco, Ica and Caucata to study collections and arrange work. As a result of these researches he was able to ship a large collection from Pisco, but his notes on his work are rather brief.

On the edge of a slight terrace close to the beach and only fifteen or twenty feet above sea level Dr. Farabee found the walls of houses completely buried in the sand. They were built of adobe, four to six feet high and five feet thick. Just behind this group of houses he found a cemetery of peculiar type, composed entirely of graves of young llamas without a single adult animal. Some thirty such burials were dug up in a small space, but with them there was nothing of interest.

Image Number: 18810

Across the bay Dr. Farabee’s explorations yielded little of interest for an article that does not deal with the more technical side of at chology. The same is true of the shell heaps that he found below Puntillo, along the beach, and his researches at Pisco.

In a letter written on November 18th, Dr. Farabee, evidently feeling considerably better and confident of speedy recovery, outlined his plans for the continuation of his expedition, an ambitious project, only a small portion of which fate was to permit him to realize. He planned to spend a few days with the little known Uros Indians of western Bolivia near Lake Titicaca, and to make extended researches on the Araucanian Indians of central Chile. Then he wished to cross the Andes and to work for some time in Argentina, both excavating and making ethnological investigations among the Pata-gonians, and finally to study the lowly Botocudos of eastern Brazil, the “real cannibals of Brazil,” as he termed them. Of this extensive program, only the work with the Araucanian Indians was realized.

On November 19th Dr. Farabee left Pisco and on the following day visited the hospital in Lima, remaining in the city several days. Between November 28th and December 6th he evidently made a hasty trip to Mollendo and Arequipa and back, whether for health or business is not stated, remaining in Lima then until December 13th. Again on December 14th he proceeded to Mollendo and Arequipa and on the 17th, in company with Mrs. Farabee, sailed on the British steamer Ebro for Chile. This steamer he took, he wrote, in order to have the attention of a “white” physician, as he was “not entirely recovered and thirty pounds light.” The Ebro stopped at Arica, Iquique, Antofagasta, and on the 21st arrived at Valparaiso, the principal seaport of Chile.

Image Number: 25186

While waiting for the day scheduled for its departure from Valparaiso, the Ebro, in order to beguile the time pleasantly for its tourists, undertook a side trip to Juan Fernandez Island, a lonely islet in the Pacific, nearly five hundred miles from the Chilean coast. Dr. Farabee, feeling very ill, was glad to seize the opportunity of a sea voyage of a few days, and at dawn of the day before Christmas, 1922, they reached the island. The little isle, only thirteen miles long by four miles wide, is of a volcanic nature, precipitous and rugged, covered with a dense humid verdure. There are few trees, however, and before its discovery it was utterly uninhabited by man or by any mammal. The largest hummingbird known is found on the island of Juan Fernandez, but its principal claim to fame is as Robinson Crusoe’s island. The original of Defoe’s immortal work, Alexander Selkirk, a sailor, was landed on this island at his own request after a quarrel with his captain in 1704, and here he remained in solitude, monarch of all he surveyed, for four years and four months, until taken off by another vessel. A tablet is erected to him upon a hill with a marvellous view where he sat in lonely contemplation day after day scanning the horizon eagerly for a sail. These facts of Selkirk’s exile are well attested, but the story of Robinson Crusoe which was based upon it is, of course, mainly imaginary.

One day the Farabees spent on Juan Fernandez Island, and, leaving there at midnight on Christmas Eve and spending the Yuletide (which in this region occurs in midsummer) at sea, they again reached Valparaiso on December 26th, and the following day proceeded to Santiago. They apparently spent from that time until January 8th recuperating and preparing for the next expedition, that to the Araucanian Indians in south central Chile.

Image Number: 25274

The Araucanians are a vigorous, independent nation, or at any rate were so until recently, before they became debauched and debased by “civilized” conditions. In many respects they resemble our own Indians of the great plains, free, independent, warlike, vigorous and upstanding, with many noble qualities. They are fine horsemen, but, like our own western Indians, unduly given to strong drink. They bear the honor of having been probably the only American nation successfully to resist all invasion of their territories. The conquering armies of the Peruvian Incas learned this to their cost when they endeavored to extend their empire ever further south in the days before the Spanish Conquest, and the southern boundary of the Inca Empire was set at the northern limit of Araucanian territory. The Spanish conquerors succeeded but little better, and after a century of guerilla warfare the independence of the Araucanians within the Moluche district was recognized by treaty.

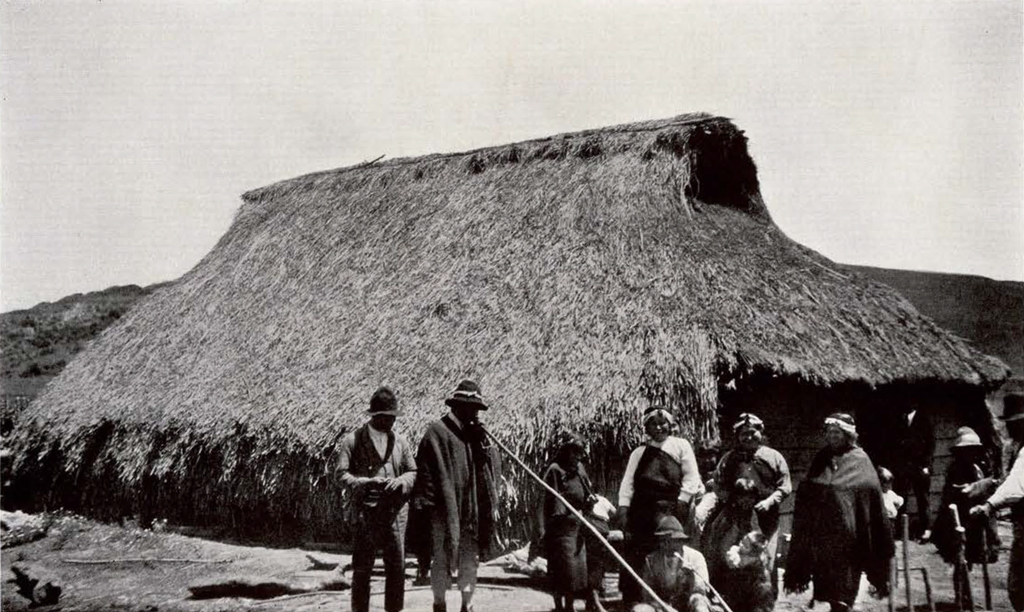

The Mapuche, as the Araucanians term themselves, probably immigrated into Chile from the pampas of Argentina in pre-Inca days, for they are evidently closely akin to the Tehuelche of Patagonia, although speaking a different language, one probably adopted from the earlier populations which they displaced. Like the Patagonians, they were nomadic hunters, hunting the guanaco and the rhea (the South American ostrich) with the bolas. The introduction of the horse gave them wider range and modified their culture considerably, and in recent years the settling of the country and the diminution of game have affected them exactly as they have the Indians of our western states. From a nomadic, hunting life, they have been compelled to adopt the agricultural method of existence and are showing considerable progress in this. All the land around Temuco, a town of ten thousand inhabitants in which few Araucanians live, is owned by Indians and affords them bountiful crops of wheat. As on our Indian reservations, they are not allowed to sell their lands.

Dr. and Mrs. Farabee left Santiago on January 8th for Temuco and remained until January 29th in Araucanian territory at Temuco, Puerto Saavedra and Kepi. In these three weeks, Dr. Farabee did a great amount of work with the natives. He secured for the University Museum a valuable collection illustrating their life, consisting mainly of the fine woven woolen blankets and the large heavy ornaments of beaten silver which are the principal adornment of the women. A large number of photographs were taken, illustrative of the life of the natives, especially at the fiesta of San Sebastian, one of the principal celebrations of the Araucanians, held only once each year and which the Farabees were lucky enough to observe.

A notebook full of scientific observations on the Mapuche was made by Dr. Farabee which will make an important contribution to anthropological literature. This includes vocabularies, physical measurements, folklore, terms of relationship, name derivation, and ethnological notes in material culture, religion, witchcraft and shamanism, marriage and burial customs, all of which are too technical and voluminous for even a resume to be given here.

This was the last piece of field research done by Dr. Farabee. Returning to Santiago on January 30th, Mrs. Farabee was taken ill for several days, which delayed their departure for Buenos Aires. On February 5th they left Santiago over the Inter-Andean railroad, a road of magnificent scenery and wonderful engineering accomplishments, crossing the majestic Andes and descending to the pampas of Argentina. During this journey Dr. Farabee was quite ill. Reaching Buenos Aires, he went to the hospital for treatment and remained five days. Two weeks longer they spent in the Capital of the Argentine. Finally on March 1st they took the Pan American train for Rio de Janeiro, and passing through Montevideo, Santos and Sao Paulo, they reached the beautiful metropolis on March 7th. In Rio Dr. Farabee spent two weeks, doubtless in the same fashion as at Buenos Aires, visiting hospitals in search of medical relief and museums for study. On the 21st, accompanied by his wife, he went on board the steamer Western World and on April 3rd arrived in New York. He was still full of courage but his little remaining strength was unequal to further effort.

Dr. Farabee never regained sufficient health to resume his official duties at the University Museum. He never again saw the valuable collections which he had secured nor was he ever able to prepare for publication any of his important scientific data. For over two years, with failing strength but indomitable determination, he fought for life. His malady had developed into pernicious anæmia, and after his long illness, on June 24, 1925, he died at his home town of Washington, Pennsylvania, in the sixtieth year of his age.

Image Number: 25009

Image Number: 25112

1 Vide THE MUSEUM JOURNAL, XVI, 2, June, 1925.↪

2 The proper name is not quite certain, as it is a small place not mentioned on maps or in archaeological literature. Dr. Farabee writes it both as Estaqueria and Estaqueira. The root is doubtless connected with estaca, “stake,” and estacada, “stockade.” Estaquerilla would be the most likely spelling.↪